Abstract

Background

The prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in 755 skinless, boneless retail broiler meat samples (breast, tenderloins and thighs) collected from food stores in Alabama, USA, from 2005 through 2011 was examined. Campylobacter spp. were isolated using enrichment and plate media. Isolates were identified with multiplex PCR assays and typed with pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). Data were analyzed by nominal variables (brand, plant, product, season, state and store) that may affect the prevalence of these bacteria.

Results

The average prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in retail broiler meat for these years was 41%, with no statistical differences in the prevalence by year (P > 0.05). Seasons did not affect the prevalence of C. jejuni but statistically affected the prevalence of C. coli (P < 0.05). The prevalence by brand, plant, product, state and store were different (P < 0.05). Establishments from two states had the highest prevalence (P < 0.05). C. coli and C. jejuni had an average prevalence of 28% and 66%, respectively. The prevalence of C. coli varied by brand, plant, season, state, store and year, while the prevalence of C. jejuni varied by brand, product, state and store. Tenderloins had a lower prevalence of Campylobacter spp. than breasts and thighs (P < 0.05). Although no statistical differences (P > 0.05) were observed in the prevalence of C. jejuni by season, the lowest prevalence of C. coli was recorded from October through March. A large diversity of PFGE profiles was found for C. jejuni, with some profiles from the same processing plants reappearing throughout the years.

Conclusions

The prevalence of Campylobacter spp. did not change during the seven years of the study; however, it did change when analyzed by brand, product and state. Seasons did not affect the prevalence of C. jejuni, but they did affect the prevalence of C. coli. Larger PFGE databases are needed to assess the temporal reoccurrence of PFGE profiles to help predict the risk associated with each profile.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

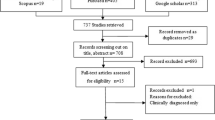

Campylobacteriosis is one of the most important foodborne diseases worldwide. The number of reported cases varies by country. For instance, New Zealand had the highest incidence with 161.1 cases for every 100,000 population in 2008 [1]. Canada had an incidence of 36.1 cases for every 100,000 person per years [2], and European countries have an overall incidence of 48 cases per 100,000 population [3]. In Scotland, there were 95.3 reported cases per 100,000 in 2006 [4]. In the US, campylobacteriosis is the third most important bacterial foodborne disease, with an incidence of 12 cases per 100,000 [5]. Campylobacter spp. are still found at high prevalence in retail broiler carcasses [6, 7] and in retail broiler meat [8–10]. In the USA, the U. S. Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Services (USDA FSIS) has recently updated the compliance guideline for poultry slaughter to make the regulations related to Salmonella detection more stringent and to enforce the implementation of a performance standard for Campylobacter spp. [11].

Although there have been recent reports reviewing the incidence of campylobacteriosis per year [5] and the prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in processed carcasses [7], there are no recent reports on the prevalence of these bacteria in retail broiler meat. In addition, the reports of prevalence are always presented without analyzing the data by nominal variables, i.e. processing plant, product, season, state and store that may influence the prevalence of these bacteria in retail broiler meat. This publication summarizes the prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in skinless, boneless retail broiler meat from 2005 to 2011. Besides describing the prevalence per year, the prevalence by brand, plant, product, season, state, store, and Campylobacter spp. found in the products are described. In addition, the results of typing these Campylobacter isolates by pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) to determine the DNA relatedness of isolates from the same processing plants but from different years are presented.

Methods

Sample collection

A total of 755 skinless, boneless retail broiler meat samples were analyzed from 2005 through 2011 from four retail stores in Auburn, Alabama and three stores in Montgomery, Alabama. Samples included breasts, tenderloins (comprised of the muscle pectoralis minor) and thighs. All samples were tray packs of approximately 1–2 lbs. More samples were processed during the months of summer than in winter.

Sample preparation and enrichment procedures

From each tray pack, 25 g of product were weighed and placed in sterile Whirl-Pak® bags (Nasco, Fort Atkinson, WI). Meat samples were enriched at a 1:4 ratio (w:v) in modified Bolton broth supplemented only with cefoperazone (33 mg per l), amphotericin B (4 mg per l) and 5% lysed horse blood. Samples were enriched for 48 h at 42°C under microaerobic atmosphere (10% CO2, 5% O2, and 85% N2, AirGas South, Inc., Montgomery, AL), which was added to anaerobic jars with an evacuation replacement system (MACSmics Jar Gassing System, Microbiology International, Frederick, MD).

Isolation of Campylobacterspp

Enriched samples (broth) were plated (~0.1 ml) on modified charcoal cefoperazone deoxycholate agar (mCCDA) for isolation and identification of Campylobacter spp. In 2009, 2010 and 2011, a slight modification was made to the protocol. For each sample, 0.1 ml of the enrichment broth was transferred to an mCCDA plate using a filter membrane as described elsewhere [12]. All agar plates were incubated at 42°C under microaerobiosis for 48 h. Suspected Campylobacter colonies were observed under phase contrast microscopy (Optiphot-2, Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY, or BX51, Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA) for their spiral morphology and darting motility. A small amount of growth from each plate was transferred to modified Campy-Cefex (mCC) agar plates supplemented with cefoperazone (33 mg), amphotericin B (4 mg) and 5% lysed horse blood. Plates were incubated at 42°C for 24 h under microaerobic conditions, and from these plates DNA was extracted using the Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification Kit as described by the manufacturer (Promega, Madison, WI) but without the RNA digestion step, and plugs were made for PFGE analysis. Isolates were stored at −80°C in tryptic soy broth (TSB, Difco, Detroit, MI) supplemented with 30% glycerol (vol/vol) and 5% horse blood.

Identification of isolates using mPCR assays

Isolates were identified as C. jejuni or C. coli using two multiplex PCR (mPCR) assays: one based on primers targeting the ask gene of C. coli[13] and the hipO gene of C. jejuni[14], and the other targeting the ask gene of C. coli (different primers from the previous mPCR) and the glyA gene of C. jejuni[15]. PCR assays were performed in 25 μl aliquots using pre-made mixes of GoTaq® (Promega) or EconoTaq® PLUS (Lucigen, Middleton, WI). The assays were performed in a DNA Engine® Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) as previously described [10, 15]. Amplified products were detected by gel electrophoresis stained with ethidium bromide and visualized using the VersaDoc™ Imaging System (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

PFGE analysis of isolates

PFGE was performed on isolates as previously described [15, 16]. Briefly, DNA was digested with SmaI and separated using a CHEF DR II system (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Braenderup strain H9812 (ATCC BAA-664) was used as the DNA size marker, and TIFF images of gels stained with ethidium bromide were loaded into BioNumerics version 6 (Applied Maths, Austin, TX) for analysis. Pairwise-comparisons were performed with the Dice correlation coefficient, and cluster analyses were performed with the unweighted pair group mathematical average (UPGMA) clustering algorithm. The optimization and position tolerance for band analysis were set at 2 and 4%, respectively, and similarity among PFGE restriction patterns was set at 90% [17].

Diversity index calculation

To assess the diversity of the PFGE profiles, the SID was calculated for the PFGE grouping and by Campylobacter spp. (C. jejuni or C. coli) [18, 19].

Statistical analysis

Results were analyzed with the Fisher's Exact Test for count data and the Kruskal-Wallis test to determine differences in nominal variables (brand, plant, product, season, state and store). The confidence interval (95%) for each proportion of positive per year was also calculated. Statistical differences were set at P ≤ 0.05 and P ≤ 0.01 for the chi-square and the Kruskal-Wallis tests, respectively. Data were not assumed to have a normal distribution. All the statistical analyses were performed with R [20].

Results

From 755 samples analyzed, 308 (41%) were positive for Campylobacter spp., with 85 (28%) of the isolates identified as C. coli and 204 (66%) identified as C. jejuni. Nineteen isolates (6%) were presumptively identified as Campylobacter spp. but were not recoverable from −80°C. These isolates were lost between 2005 and 2009 (Tables 1 and 2). The average prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in retail broiler meat per year had a standard deviation of 5.4, and the standard deviation for the average prevalence for C. coli and C. jejuni was 18 and 17, respectively. Table 1 shows the prevalence of Campylobacter coli and C. jejuni per year.

Table 2 shows the percentage distribution of C. coli and C. jejuni by product (breast, tenderloin or thigh). The Fisher's Exact Test for count data showed that tenderloins had a lower prevalence of Campylobacter spp. than breasts (P = 0.003) and thighs (P < 0.001). In 2005, the ratio C. coli:C. jejuni was different from the other years, with a higher percentage of C. coli than C. jejuni for that particular year (Table 1).

No statistical differences were seen in the prevalence of C. jejuni by season (Table 3 and Table 4), although the months of October through March showed the highest number of C. jejuni and the lowest number of C. coli (Table 3). The data showed that two states had processing plants where the prevalence was highest (Table 5), and the Kruskal-Wallis (KW) rank sum test for categorical variables showed again that the prevalence of C. jejuni was not influenced by season. However, the prevalence was influenced by brand, plant, product, state and store (Table 4). The prevalence of C. coli appeared to vary by brand, plant, season, state and store.

PFGE analysis of isolates from the same processing plants but from different years showed a large variability of PFGE profiles. However, some PFGE types re-appeared in different years (Figure 1). Table 6 shows the Simpson's index of diversity (SID) for 175 C. jejuni isolates and 78 C. coli isolates, including the variability of types by years for C. jejuni isolates.

Diversity of PFGE profiles. This picture shows the diversity of the C. jejuni PFGE profiles from the same processing plant but different years. PFGE patterns re-appeared at different years, suggesting that few predominant PFGE patters are associated to a given processing plant. A cut-off of 90%, based on previous studies [32, 36], was used to separate PFGE subtypes.

Discussion

There have not been recent reports on the prevalence of Campylobacter in retail broiler meat in the USA. Most of the studies include products with skin, and the samples are taken during processing where the carcasses are still intact and before portioning. The more recent publication summarizing the prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in processed carcasses comes from the nationwide microbiological baseline data collection program by the USDA FSIS. These data were collected from July 2007 through June 2008 and showed a prevalence of 40% Campylobacter positive in carcasses post-chill [7]. Yet, most of the broiler meat sold in stores across the US is sold in tray packs and include boneless, skinless products.

Because Campylobacter spp. are at low numbers in retail broiler meat in the USA [7], concentration by centrifugation [21] and filtration have been performed to increase the number of Campylobacter cells before plating [8, 22]. Bolton broth was used in this study because this medium has been used most frequently for isolation of Campylobacter from poultry samples [23, 24], and it appears to be one of the best available alternatives to compromise between the inhibition of competitors and the growth of Campylobacter spp. [25]. The data in Table 1 are similar to most recent reports on the prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in retail samples in the US [9, 10, 21]. This prevalence is similar to the data from Belgium [26], but lower than the reports from Ireland [27], England [28, 29], Canada [30], Japan [31] and Spain [32]. The prevalence among different countries varies from as low as 25% in Switzerland to as high as 100% in the Czech Republic [31, 33, 34].

The low prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in tenderloins has been previously reported [9, 10]. The fluctuation in the prevalence of C. coli and C. jejuni by year has not been previously addressed. However, more surveillance data is necessary to understand the extent of this fluctuation, which may be comprised of an actual variability by year and/or an artifactual variability due to the methodology used for isolation. It has been shown that analyzing more than 25 g of sample increases the chances of recovering positive samples for Campylobacter spp. [35]. Therefore, there is no optimal methodology to determine the true prevalence of these bacteria, and for all purposes the actual prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in retail broiler meat may be underestimated. An optimal methodology that could detect the true number of positive samples and/or the samples with the highest number of Campylobacter spp. would provide a more accurate prevalence for surveillance purposes of these pathogens in retail broiler meat.

There is substantial information suggesting that the predominant Campylobacter spp. present in commercial broiler products are C. jejuni and C. coli, a trend that is especially clear in industrialized nations [27, 28, 36]. Because Campylobacter spp. are inert, very few biochemical tests are used for identification of species. These tests are mainly performed in qualified laboratories studying the taxonomy of these bacteria where several controls are evaluated in parallel to avoid false identification. Therefore, molecular techniques, mainly the polymerase chain reaction validated by sequencing and Southern blotting, provide simple, robust identification to the species level. In a recent summary of the current Campylobacter spp. worldwide prevalence, C. jejuni was the predominant Campylobacter spp. isolated from retail poultry with the exception of Thailand and South Africa, where the predominant species was C. coli[31]. In some countries, C. coli represents less than 20% of all the Campylobacter isolates found in retail broiler meats [31, 37, 38]; yet, they are at a prevalence that exceeds 20% in live broiler chickens. This difference may be explained by the isolation procedure: direct plating is used to analyze fecal material from live animals, while enrichment is used to analyze retail broiler meat. Both Campylobacter spp. have been found in enriched retail samples [10], but it is not clear if enrichment procedures hinder one species versus the other, or favor the species that contain more vegetative cells at the beginning of the enrichment procedure.

Although other countries, such as Denmark, have shown a strong seasonal correlation in the prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in broiler flocks and in retail broiler meat [38], there were no seasonal variations detected in C. jejuni. Although statistical differences were seen for C. coli, a larger database is needed to confirm these results. There is no long-term data to assess the changes in the prevalence of Campylobacter spp. present in retail broiler meats. The results from 2005 clearly show that C. coli was the predominant species. These strains were tested with the same PCR assays as the rest of the data set; therefore, there is no bias in the methodology for identification. These data suggest that the product, the processing plant, the region, and even the season, may impact the prevalence of these pathogens in retail broiler meats.

A large diversity in the PFGE profiles of Campylobacter spp. has been reported in the literature [8, 28], with the greatest diversity found in Campylobacter isolates from broiler chickens [28]. This diversity can be related to the larger database available for broiler chickens. This diversity may also be due to a true variability of types, meaning that Campylobacter strains found in chickens show more diversity than the Campylobacter strains isolated from other animal species. The diversity of Campylobacter strains by PFGE has also been demonstrated in clinical samples. For instance, throughout an infection involving 52 patients, one patient had two different Campylobacter species and four patients had different Campylobacter strains based on PFGE analysis. Although human infections with more than one Campylobacter strain are rare, changes in the PFGE profiles throughout an infection complicates the epidemiological studies of Campylobacter spp. [39]. The collection and analysis of retail samples immediately before consumer exposure is the most appropriate sampling point for the collection of data that can be factored into risk analysis models. Therefore, a PFGE database of retail isolates that could be compared to PFGE patterns from human isolates may provide invaluable information to assess the actual risk of humans acquiring campylobacteriosis via consumption of retail meats.

Conclusions

The prevalence of Campylobacter spp. has not changed in the last seven years, and there is no variation in the prevalence due to seasons for C. jejuni. However, a seasonal prevalence was found for C. coli. Two states yielded more positive samples than four other states. The predominant species was C. jejuni, and PFGE analyses indicated a large diversity of types throughout the years. Some of the same PFGE types reoccurred from year to year within samples from the same processing plant. A continuous surveillance of Campylobacter spp. in retail broiler meat will provide larger PFGE databases to better assess the reoccurrence of PFGE profiles on a spatial and temporal fashion.

References

Sears A, Baker MG, Wilson N, Marshall J, Muellner P, Campbell DM, Lake RJ, French NP: Marked campylobacteriosis decline after interventions aimed at poultry, New Zealand. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011, 17: 1-18. 10.3201/eid1701.101210. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1706.101272,

Anon: C-EnterNet 2008 Annual Report, National Integrated Enteric Pathogen Surveillance Program. 2010, Public Health Agency of Canada, http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/c-enternet/pubs/2008/index-eng.php,

Anon: The European Union Summary Report on Trends and Sources of Zoonoses, Zoonotic Agents and Food-borne Outbreaks in 2010. EFSA Journal. 2012, 10 (3): 2597-10.2903/j.efsa.2012.2597. [442pp.]. Available online: www.efsa.europa.eu/efsajournal

Locking M, Browning L, Smith-Palmer A, Brownlie S: Gastro-intestinal and foodborne infections. HPS Weekly Report. 2007, 41: 3-4.

Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Angulo FJ, Tauxe RV, Widdowson MA, Roy SL, Jones JL, Griffin PM: Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—major pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011, 17: 7-15.

Anon: U. S. Department of Agriculture. Nationwide broiler chicken microbiological baseline data collection program (July 1994-June 1995). 1996, D.C: Food Safety Inspection Service, Washington

Anon: The nationwide microbiological baseline data collection program: Young chicken survey. July 2007– June 2008. 2009, Food Safety and Inspection Services of the U. S. Department of Agriculture, http://www.fsis.usda.gov/PDF/Baseline_Data_Young_Chicken_2007-2008.pdf,

Dickins MA, Franklin S, Stefanova R, Shutze GE, Eisenach KD, Wesley IV, Cave D: Diversity of Campylobacter isolates from retail poultry carcasses and from humans as demonstrated by pulsed-filed gel electrophoresis. J Food Prot. 2002, 65: 957-962.

Liu L, Hussain SK, Miller RS, Oyarzabal OA: Efficacy of Mini VIDAS for the detection of Campylobacter spp. from retail broiler meat enriched in Bolton broth with or without the supplementation of blood. J Food Prot. 2009, 72: 2428-2432.

Oyarzabal OA, Backert S, Nagaraj M, Miller RS, Hussain SK, Oyarzabal EA: Efficacy of supplemented buffered peptone water for the isolation of Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli from broiler retail products. J Microbiol Methods. 2007, 69: 129-136. 10.1016/j.mimet.2006.12.011.

Anon: New Performance standards for Salmonella and Campylobacter in young chicken and turkey slaughter establishments: response to comments and announcement of implementation schedule. Federal Register. 2011, 76: 15282-15290.

Speegle L, Miller ME, Backert S, Oyarzabal OA: Research Note: Use of cellulose filters to isolate Campylobacter spp. from naturally contaminated retail broiler meat. J Food Prot. 2009, 72: 2592-2596.

Linton D, Lawson AJ, Owen RJ, Stanley J: PCR detection, identification to species level, and fingerprinting of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli direct from diarrheic samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1997, 35: 2568-2572.

Persson S, Olsen KEP: Multiplex PCR for identification of Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni from pure cultures and directly on stool samples. J Med Microbiol. 2005, 54: 1043-1047. 10.1099/jmm.0.46203-0.

Zhou P, Hussain SK, Liles MR, Arias CR, Backert S, Kieninger J, Oyarzabal OA: A simplified and cost-effective enrichment protocol for the isolation of Campylobacter spp. from retail broiler meat without microaerobic incubation. BMC Microbiol. 2011, 11: 175-10.1186/1471-2180-11-175.

Behringer M, Miller WG, Oyarzabal OA: Typing of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolated from live broilers and retail broiler meat byflaA-RFLP, MLST, PFGE and REP-PCR. J Microbiol Methods. 2010, 84: 194-201.

De Boer P, Duim B, Rigter A, van der Plas J, Jacobs-Reitsma W, Wagenaar JA: Computer-assisted analysis and epidemiological value of genotyping methods for Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. J Clin Microbiol. 2000, 38: 1940-1946.

Hunter PR: Reproducibility and indices of discriminatory power of microbial typing methods. J Clin Microbiol. 1990, 28: 1903-1905.

Hunter PR, Gaston MA: Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson's index of diversity. J Clin Microbiol. 1988, 26: 2465-2466.

Anon: R: A language and environment for statistical computing.R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. 2010, Austria: R Development Core Team, http://www.R-project.org,

Nannapaneni R, Story R, Wiggins KC, Johnson MG: Concurrent quantitation of total Campylobacter and total ciprofloxacin-resistant Campylobacter loads in rinses from retail raw chicken carcasses from 2001 to 2003 by direct plating at 42°C. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005, 71: 4510-4515. 10.1128/AEM.71.8.4510-4515.2005.

Willis WL, Murray C: Campylobacter jejuni seasonal recovery observations of retail market broilers. Poult Sci. 1997, 76: 314-317.

Anon: Health Protection Agency. Detection of Campylobacter species. 1998, National Standard Method F21, 2http://www.hpa-standardmethods.org.uk/documents/food/pdf/F21.pdf,

Paulsen P, Kanzler P, Hilbert F, Mayrhofer S, Baumgartner S, Smuldrs FJM: Comparison of three methods for detecting Campylobacter spp. in chilled or frozen meat. Int J Food Microbiol. 2005, 103: 229-233. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.12.022.

Baylis CL, MacPhee S, Martin KW, Humphrey TJ, Betts RP: Comparison of three enrichment media for the isolation of Campylobacter spp. from foods. J Appl Microbiol. 2000, 89: 884-891. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.01203.x.

Habib I, Sampers I, Uyttendaele M, Berkvens D, De Zutter L: Baseline data from a Belgium-wide survey of Campylobacter species contamination in chicken meat preparations and considerations for a reliable monitoring program. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008, 74: 5483-5489. 10.1128/AEM.00161-08.

Madden RH, Moran L, Scates P, McBride J, Kelly C: Prevalence of Campylobacter and Salmonella in raw chicken on retail sale in the republic of Ireland. J Food Prot. 2011, 74: 1912-1916. 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-11-104.

Kramer JM, Frost JA, Bolton FJ, Wareing DRA: Campylobacter contamination of raw meat and poultry at retail sale: Identification of multiple types and comparison with isolates from human infection. J Food Prot. 2000, 63: 1654-1659.

Jørgensen F, Bailey R, Williams S, Henderson P, Wareing DR, Bolton FJ, Frost JA, Ward L, Humphrey TJ: Prevalence and numbers of Salmonella and Campylobacter spp. on raw, whole chickens in relation to sampling methods. Int J Food Microbiol. 2002, 76: 151-164. 10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00027-2.

Bohaychuk VM, Gensler GE, King RK, Manninen KI, Sorensen O, Wu JT, Stiles ME, Mcmullen LM: Occurrence of pathogens in raw and ready-to-eat meat and poultry products collected from the retail marketplace in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. J Food Prot. 2006, 69: 2176-2182.

Suzuki H, Yamamoto S: Campylobacter contamination in retail poultry meats and by-products in the world: a literature survey. J Veterinary Medical Science. 2009, 71: 255-261. 10.1292/jvms.71.255.

Mateo E, Cárcamo J, Urquijo M, Perales I, Fernández-Astorga A: Evaluation of a PCR assay for the detection and identification of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli in retail poultry products. Res Microbiol. 2005, 156: 568-574. 10.1016/j.resmic.2005.01.009.

Hochel I, Viochna D, Skvor J, Musil M: Development of an indirect competitive ELISA for detection of Campylobacter jejuni subsp. jejuni O:23 in foods. Folia Microbiol (Praha). 2004, 49: 579-586. 10.1007/BF02931537.

Ledergerber U, Regula G, Stephan R, Danuser J, Bissig B, Stärk KD: Risk factors for antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter spp. isolated from raw poultry meat in Switzerland. BMC Public Health. 2003, 93: 39-

Oyarzabal OA, Liu L: Significance of sample weight and enrichment ratio on the isolation of Campylobacter spp. from retail broiler meat. J Food Prot. 2010, 73: 1339-1343.

Atanassova V, Ring C: Prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in poultry and poultry meat in Germany. Int J Food Microbiol. 1999, 51: 187-190. 10.1016/S0168-1605(99)00120-8.

Gurtler M, Alter T, Kasimir S, Fehlhaber K: The importance of Campylobacter coli in human campylobacteriosis: prevalence and genetic characterization. Epidemiol Infect. 2005, 133: 1081-1087. 10.1017/S0950268805004164.

Boysen L, Vigre H, Rosenquist H: Seasonal influence on the prevalence of thermotolerant Campylobacter in retail broiler meat in Denmark. Food Microbiol. 2011, 28: 1028-1032. 10.1016/j.fm.2011.02.010.

Steinbrueckner B, Ruberg F, Kistv M: Bacterial genetic fingerprint: a reliable factor in the study of the epidemiology of human Campylobacter enteritis?. J Clin Microbiol. 2001, 39: 4155-4159. 10.1128/JCM.39.11.4155-4159.2001.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank S. K. Hussain, R. S. Miller, L. Liu, L. Speegle, Danielle Liverpool and KaLia Burnette for their help in collecting and processing the samples and in the identification of isolates. DL and KB were supported by grant 0754966 from the Research Experiences for Undergraduates Program of the Biology Directorate of the National Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Authors' contributions

AW collected and analyzed part of the samples and identified the isolates. AW performed the PFGE analysis. OAO conceived and coordinated the study and designed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and accepted the final version of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Williams, A., Oyarzabal, O.A. Prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in skinless, boneless retail broiler meat from 2005 through 2011 in Alabama, USA. BMC Microbiol 12, 184 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-12-184

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-12-184