Abstract

Background

The world-wide increase of foodborne infections with antibiotic resistant pathogens is of growing concern and is designated by the World Health Organization as an emerging public health problem. Thermophilic Campylobacter have been recognised as a major cause of foodborne bacterial gastrointestinal human infections in Switzerland and in many other countries throughout the world. Poultry meat is the most common source for foodborne cases caused by Campylobacter. Because all classes of antibiotics recommended for treatment of human campylobacteriosis are also used in veterinary medicine, in view of food safety, the resistance status of Campylobacter isolated from poultry meat is of special interest.

Methods

Raw poultry meat samples were collected throughout Switzerland and Liechtenstein at retail level and examined for Campylobacter spp. One strain from each Campylobacter-positive sample was selected for susceptibility testing with the disc diffusion and the E-test method. Risk factors associated with resistance to the tested antibiotics were analysed by multiple logistic regression.

Results

In total, 91 Campylobacter spp. strains were isolated from 415 raw poultry meat samples. Fifty-one strains (59%) were sensitive to all tested antibiotics. Nineteen strains (22%) were resistant to a single, nine strains to two antibiotics, and eight strains showed at least three antibiotic resistances. Resistance was observed most frequently to ciprofloxacin (28.7%), tetracycline (12.6%), sulphonamide (11.8%), and ampicillin (10.3%). One multiple resistant strain exhibited resistance to five antibiotics including ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, and erythromycin. These are the most important antibiotics for treatment of human campylobacteriosis. A significant risk factor associated with multiple resistance in Campylobacter was foreign meat production compared to Swiss meat production (odds ratio = 5.7).

Conclusion

Compared to the situation in other countries, the data of this study show a favourable resistance situation for Campylobacter strains isolated from raw poultry meat produced in Switzerland. Nevertheless, the prevalence of 19% ciprofloxacin resistant strains is of concern and has to be monitored. "Foreign production vs. Swiss production" was a significant risk factor for multiple resistance in the logistic regression model. Therefore, an adequate resistance-monitoring programme should include meat produced in Switzerland as well as imported meat samples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The importance of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli as foodborne pathogens has steadily increased during the last years. With an incidence of 92 reported cases per 100'000 inhabitants, Campylobacter spp. are the leading cause of bacterial zoonosis in Switzerland [1]. Inadequately cooked meat, particularly poultry, unpasteurised milk and contaminated drinking water are the most common sources for epidemic and sporadic foodborne cases [2, 3]. Due to the often self-limiting diarrhoea in humans, antibiotic treatment is normally not required. Nevertheless, antibiotic treatment is indicated for severe and prolonged enteritis, septicaemia, and for persons at risk such as very young or immuno-compromised patients. Besides erythromycin, which is the antibiotic of choice, fluoroquinolones and tetracycline are commonly used [4]. Particularly fluoroquinolones are first-line drugs for empiric therapy of acute diarrhoea, as they are effective against most major pathogens causing bacterial enteritis [5, 6]. Therefore, most cases of campylobacteriosis receiving antibiotic treatment will initially be treated with fluoroquinolones. Worrying is the fact, that in recent years a rapidly increasing proportion of Campylobacter isolates from humans and animals all over the world were found to be resistant to fluoroquinolones [7–11]. This coincided with initiation of the use of the fluoroquinolones to food animals in many countries [12–15].

The objectives of this study were i) to determine the prevalence of antibiotic resistant Campylobacter strains in raw poultry meat samples at retail level, and ii) to identify possible risk factors associated.

Methods

For sampling, 122 retail stores throughout Switzerland and Liechtenstein were randomly selected. From March until July 2002, food safety inspectors of the cantonal laboratories collected 415 samples of raw poultry meat (whole chickens as well as parts such as cutlet, meat cut into strips, legs, drumsticks, wings, and breast) from selected stores. Additionally, information about housing type of the poultry (as labelled), the country of origin (as labelled), refrigeration (chilled, frozen), and packing of the samples was recorded.

Of each sample, 10 g was inoculated into 100 ml selective enrichment broth (Brucella broth (211088, Becton Dickinson, Sparks, USA) with Campylobacter growth and selective supplement (SR084E, SR069E, Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK)) and incubated at 42°C for 24 h under microaerobic conditions provided by commercial gas packs (CampyGen from Oxoid). After enrichment the samples were streaked on selective agar media (Brucella agar (211086 Becton Dickinson) with 6% horse blood (SR0048C, Oxoid)) as well as Butzler Campylobacter selective supplement (SR085E, Oxoid) and incubated at 42°C for another 24 h under microaerobic conditions. Translucent white, moist and glistening colonies were picked and taken for further identification. Identification of Campylobacter strains was performed using the following standard tests: gram-negative stain, characteristic motion, catalase- and oxidase reactions, aerobic growth. One strain from each Campylobacter-positive sample was selected for susceptibility testing.

The disc diffusion method was performed as recommended by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards [16]. The following antibiotic impregnated discs (bioMérieux SA, France) were used: erythromycin (15 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), tetracycline (30 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), streptomycin (10 μg), ampicillin (10 μg), amoxicillin (25 μg) and sulphonamide (20 μg). Three to five isolated colonies of the same morphological type were selected from the agar plate culture and transferred into trypticase soy broth (211768, Becton Dickinson). After incubation at 42°C for 24 h under microaerobic conditions a sterile cotton swab was dipped into the suspension and streaked on the entire surface of a Mueller-Hinton agar (CM 337, Oxoid) with 5% sheep blood. Four antibiotic discs were placed on each plate and after 48 h of microaerobic incubation at 42°C the diameter of the inhibition zone was measured with calipers. E. coli ATCC 25922 and S. aureus ATCC 25923 were used as reference strains. Zones of growth inhibition were evaluated according to the NCCLS standards.

The E-test (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) was performed for erythromycin, ciprofloxacin and tetracycline on Mueller-Hinton agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood according to the manufacture's instructions. Inocula were prepared by incubating the strains for 24 h at 42°C under microaerobic conditions in trypticase soy broth. After application of the E-test strips, plates were incubated in microaerobic conditions at 42°C for 48 h. The minimal inhibition concentration (MIC) was read directly from the test strip at the point where the elliptical zone of inhibition intersected the MIC scale on the strip. The following NCCLS zone diameter (mm) and MIC breakpoints for resistance were applied: erythromycin ≤ 13 mm and MIC ≥ 8 mg/l, ciprofloxacin ≤ 15 mm and MIC ≥ 4 mg/l, tetracycline ≤ 14 mm and MIC ≥ 16 mg/l, streptomycin ≤ 11 mm, ampicillin ≤ 13 mm, gentamicin ≤ 12 mm, amoxicillin ≤ 13 mm and sulphonamide ≤ 12 mm.

Statistical analysis consisted of initial bivariate screening for possible risk factors associated with resistance to the tested antibiotics. Variables screened for were:

• production system: free range production or production with bedding and winter garden, labelled as 'animal friendly' vs. conventional production

• foreign production vs. Swiss production

• whole chicken vs. parts of chicken

• products sold pre-packed vs. products sold in open displays

• chilled products vs. frozen products

A χ2 test was applied to determine significance in bivariate screening. Factors significantly associated with antibiotic resistance (p < 0.05) were included into a multiple logistic regression model. Variable selection was performed by stepwise backward selection. Only significant variables (p < 0.05) were retained in the model. For each tested antibiotic, a separate regression analysis was performed. In addition, risk factors for multiple resistance, defined as resistance to at least two of the tested antibiotics, were determined in a separate regression model. All statistical analyses were performed with the statistical software package NCSS 2000 (Number Cruncher Statistical Systems, Kaysville, Utah, USA).

Results

Samples

Overall, 415 samples of raw poultry meat products were purchased from 122 retail shops and cultured for Campylobacter spp. Information about housing type of poultry, processing, packing, refrigeration, and the country of origin of the sampled poultry products is given in table 1.

Campylobacter prevalence

Ninety-one out of 415 (21.9%) raw poultry meat samples were found to be positive for Campylobacter spp. As the meat samples were purchased only between March and July, no seasonal trend for prevalence of positive samples could be observed. There was no statistically significant difference between housing types. The prevalence of Campylobacter positive samples was 20.4% for conventionally produced poultry, and 24% for 'animal-friendly' produced poultry. Furthermore, no statistically significant difference was found for the origin of the meat (21% for imported products and 22.3% for Swiss products), the product categories (21.3% for samples from whole chicken and 22.4% for samples from parts of chicken), and the package (21.4% for pre-packed products and 23.4% for products sold in open displays). Frozen products had a statistically significant lower prevalence of Campylobacter positive samples than chilled products (7.9% and 25.1%, respectively; OR = 4.3; 95%CI 1.8–10.3).

Susceptibility testing

In total, 87 Campylobacter strains were isolated for susceptibility testing. Fifty-one strains (58.6%) were sensitive to all tested antibiotics, 36 strains (41.4%) were resistant to at least one of the antibiotics. Nineteen strains (21.8%) were resistant to a single and nine strains to two antibiotics. Triple resistance was shown four times. Two strains were observed with fourfold and fivefold resistance, respectively. The resistance pattern of a fivefold resistant strain showed a striking combination of ciprofloxacin, tetracycline and erythromycin, the most important antibiotics for treatment of human campylobacteriosis. Overall, in multiple resistant isolates, patterns of resistance were heterogeneous.

In figure 1 the results of the sampled retail shops are shown with a possible classification.

Distribution and classification of retail shops. Distribution and classification of the 122 retail shops included in this study. Green dots: shops without Campylobacter-positive samples. Yellow dots: shops with at least one Campylobacter-positive sample; no antibiotic resistance. Orange dots: shops with at least one sample with Campylobacter resistant to one of the tested antibiotics. Red dots: shops with at least one sample with Campylobacter resistant to more than one antibiotic.

Using the disc diffusion method, nine (10.3%) out of 87 strains were resistant to ampicillin, twenty-five (28.7%) to ciprofloxacin, one to erythromycin (1.1%), eleven (12.6%) to tetracycline, seven (8.0%) to streptomycin and none to gentamicin. Five strains (5.9%) out of 85 tested were resistant to amoxicillin and nine (11.8%) out of 76 tested resistant to sulphonamide.

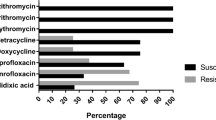

The results of susceptibility testing using the E-test method are shown in figure 2. The comparison of the results for ciprofloxacin and erythromycin showed no differences between the disc diffusion and the E-test method, whereas for tetracycline, there was one strain marginally classified as resistant using the disc diffusion method but susceptible using the E-test method.

Risk factor analysis

Figure 3 provides an overview of antibiotic resistance in isolates from 'animal-friendly' and conventional production, and from Swiss and foreign products, respectively. In bivariate analysis "conventional production system vs. 'animal-friendly' production system" (OR = 5.2; 95%CI 1.4–19.8) was one of two significant risk factors for resistance to at least two antibiotics. The second factor, "foreign production vs. Swiss production", was the only risk factor remaining significant for multiple resistance in the logistic regression model (OR = 5.7; 95%CI 1.8–17.7). Risk factors for resistance to ampicillin, amoxicillin, ciprofloxacin, and tetracycline are shown in table 2. No significant risk factors could be identified for resistance in Campylobacter strains to erythromycin, streptomycin and sulphonamide.

Discussion

The high prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in raw poultry meat samples found in this study agrees with data from other studies [17–19]. Compared to the situation in other countries, the data of this study show a favourable resistance situation for Campylobacter strains isolated from raw poultry meat produced in Switzerland. In the USA, 90% of Campylobacter strains isolated from poultry meat had resistance to at least one and 45% to at least two antibiotics [20].

In our study, 28.7% of the isolated strains were resistant to ciprofloxacin. This prevalence is comparable to the results reported in the cited American study [20]. A much higher prevalence of ciprofloxacin resistant strains was found in Austria (47%) [21], while a lower prevalence was reported in Denmark (6%) [22]. However, it has to be considered, that in our study the resistance to ciprofloxacin was significantly higher in Campylobacter spp. isolated from foreign products than from Swiss products. Nevertheless, the prevalence of ciprofloxacin resistance in Campylobacter strains from Swiss poultry meat products was 19% and thus higher than for any other antibiotic tested. Data on resistance patterns of Campylobacter isolated from humans in Switzerland only have limited validity (small number of non-representative samples). Nevertheless, the highest rates for resistance, in the last four years, were observed for nalidixid acid (over 80% of isolates) [23]. As there is strong cross resistance to fluoroquinolones which are most frequently used for empiric antimicrobial treatment of acute diarrhoea, this fact gives cause for concern. In Switzerland Baytril®(enrofloxacin) is licensed for therapeutic use in poultry and therefore, ongoing monitoring is required. Twelve point six percent of the isolated strains in our study were resistant against tetracycline. A much higher prevalence of tetracycline resistant strains was found in USA (66%), and in Austria (47%) [20, 21]. Only 7% of the strains in the Danish study were tetracycline resistant [22].

Comparable to our data, a low resistance prevalence against erythromycin was also reported in Austria and Denmark [21, 22], whereas in the USA 20% erythromycin resistant strains were found [20].

In a recent Swiss study resistance patterns of Campylobacter strains isolated from finishing pigs were investigated [24]. Whereas prevalence of resistance against ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, and gentamicin in these strains was similar to the results of this study, prevalence of resistance against erythromycin and streptomycin was 19.8% and 79.1%, respectively, and therefore much higher than in strains isolated from poultry meat. This finding is consistent with Danish data [25] finding a higher prevalence of resistance to streptomycin in Campylobacter coli, predominantly isolated in pigs, than in Campylobacter jejuni, the predominantly strain in poultry meat. Generally, the comparison of different studies turned out to be difficult because of different sample collection and varieties in culture methods and susceptibility test methods.

A noteworthy finding was the apparent clustering of retail shops with at least one sample with Campylobacter resistant to multiple antibiotics in the south of Switzerland (figure 1). This could be explained by the high proportion of imported poultry meat products in this region. However, due to sample size limitations, analysis by country of origin did not produce meaningful results. Moreover, the results of this study indicate an association between Campylobacter spp. being resistant to amoxicillin and poultry products sold in open displays. One could speculate that this astonishing result may be based on a different origin of the products. Samples from products sold in open displays were predominantly from small local butcheries. Pre-packed products, on the other hand, were primarily sampled in supermarkets. However, no data are available on the patterns of antibiotics use in poultry farms delivering to small butcheries or to supermarkets.

It is known that poultry from free range housing systems have a higher risk of being infected with Campylobacter spp. than poultry from conventional housing systems [26]. However, there was no significant association between these systems and the occurrence of antibiotic resistance in the isolated strains. While in bivariate analysis, both "conventional production vs. 'animal-friendly' production" and "foreign production vs. Swiss production" were significant risk factors for multiple resistance, only "foreign production vs. Swiss production" remained significant in the logistic regression model. This means that the univariate results were caused by confounding as the majority of 'animal-friendly' samples was produced in Switzerland.

Conclusions

In this study, the overall prevalence of ciprofloxacin resistance in Campylobacter strains from raw poultry meat (29%) was higher than the prevalence of ciprofloxacin resistance in Campylobacter strains from poultry meat produced in Switzerland (19%) and foreign versus Swiss production was a significant risk factor for multiple resistant strains in the logistic regression model. Therefore, a national monitoring program for antibiotic resistance needs to include both domestically produced and imported meat.

References

Swiss Federal Office of Public Health: Meldungen Infektionskrankheiten. Bulletin. 2003, 21: 354-

Butzler JP, Oosterom J: Campylobacter : pathogenicity and significance in foods. Int J Food Microbiol. 1991, 12: 1-8. 10.1016/0168-1605(91)90043-O.

Altekruse SF, Stern NJ, Fields PI, Swerdlow DL: Campylobacter jejuni-an emerging foodborne pathogen. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999, 5: 28-35.

Solomon EB, Hoover DG: Campylobacter jejuni : a bacterial paradox. J Food Safety. 1999, 19: 121-136.

Wistrom J, Norrby SR: Fluoroquinolones and bacterial enteritis, when and for whom?. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995, 36 (1): 23-39.

Graninger W, Zedtwitz-Liebenstein K, Laferl H, Burgmann H: Quinolones in gastrointestinal infections. Chemotherapy. 1996, 42 (Suppl 1): 43-53.

Rautelin H, Renkonen OV, Kosunen TU: Emergence of fluoroquinolone resistance in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli in subjects from Finland. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991, 35: 2065-2069.

Reina J, Borrell N, Serra A: Emergence of resistance to erythromycin and fluoroquinolones in thermotolerant Campylobacter strains isolated from feces 1987–1991. Europ J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992, 11: 1163-1166.

Velazquez JB, Jimenez A, Chomon B, Villa TG: Incidence and transmission of antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995, 35: 173-178.

Smith KE, Besser JM, Hedberg CW, Leano FT, Bender JB, Wicklund JH, Johnson BP, Moore KA, Osterholm MT: Quinolone-resistant Campylobacter jejuni infections in Minnesota, 1992–1998. Investigation Team N Engl J of Med. 1999, 340: 1525-1532. 10.1056/NEJM199905203402001.

Van Looveren M, Daube G, De Zutter L, Dumont JM, Lammens C, Wijdooghe M, Vandamme P, Jouret M, Cornelis M, Goossens H: Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Campylobacter strains isolated from food animals in Belgium. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001, 48: 235-240. 10.1093/jac/48.2.235.

Endtz HP, Ruijs GJ, van Klingeren B, Jansen WH, van der Reyden T, Mouton RP: Quinolone resistance in Campylobacter isolated from man and poultry following the introduction of fluoroquinolones in veterinary medicine. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991, 27: 199-208.

Jacobs-Reitsma WF, Kan CA, Bolder NM: The introduction of quinolone resistance in Campylobacter bacteria in broilers by quinolone treatment. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1994, 19: 228-231.

Gaunt PN, Piddock LJ: Ciprofloxacin resistant Campylobacter spp. in humans: an epidemiological and laboratory study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996, 37: 747-57.

Engberg J, Aarestrup FM, Taylor DE, Gerner-Smidt P, Nachamkin I: Quinolone and macrolide resistance in Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli: resistance mechanisms and trends in human isolates. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001, 7: 24-34.

National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards: Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disc Susceptibility Tests. Approved standards M2-A8. 2003, Wayne, NCCLS, 8

Wilson IG: Salmonella and Campylobacter contamination of raw retail chickens from different producers: a six year survey. Epidemiol Infect. 2002, 129: 635-645.

Ursinitsch B: About the epidemiology of Campylobacter spp. in Styrian broiler flocks. Doctoral thesis. 2002, University of Vienna

Denis M, Refrégier-Petton J, Laisney M-J, Ermel G, Salvat G: Campylobacter contamination in French chicken production from farm to consumers. Use of a PCR assay for detection and identification of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. J Appl Microbiol. 2001, 91 (2): 225-267. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01380.x.

Anonymous: Presence of antimicrobial resistant pathogens in chicken sold at retail: a report on tests by CI members in Australia and the United States. An Information Paper presented by Consumers International to the Codex Committee on Food Hygiene 35th Session: January 27–February 1. 2003, ; Orlando. USA

Anonymous: Resistenzmonitoring 2001. Eine flächendeckende Erhebung zum Resistenzverhalten von ausgewählten Zoonoseerregern, Indikatorbakterien und euterpathogenen Keimen in der steirischen Nutztierpopulation. REMOST 2001, Fachabteilung 8C-Veterinärwesen, Amt der Steiermärkischen Landesregierung. 2001

Anonymous: DANMAP 2002 – Use of antimicrobial agents and occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria from food animals, foods and humans in Denmark. [http://www.vetinst.dk/file/2/DANMAP_2002endelig.pdf]

Anonymous: Swiss Zoonoses Report. Magazine of the Swiss Federal Veterinary Office. 2003, 3: 13-15.

Regula G, Stephan R, Danuser J, Bissig B, Ledergerber U, Lo Fo Wong D, Stärk KDC: Reduced antimicrobial resistance to fluoroquinolones and streptomycin in 'animal-friendly' pig fattening farms in Switzerland. Vet Rec. 2001, 152: 80-81.

Aarestrup FM, Nielsen EM, Madsen M, Engberg J: Antimicrobial Susceptibility Patterns of Thermophilic Campylobacter spp. from Humans, Pigs, Cattle and Broiler in Denmark. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997, 41: 2244-2250.

Choisat B: Ein Beitrag zur Epidemiologie von Campylobacter jejuni und Campylobacter coli in Geflügelbeständen in der Schweiz. Doctoral thesis. 1997, University of Bern, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/3/39/prepub

Acknowledgements

We thank the cantonal laboratories and the laboratory of Liechtenstein for their generous collaboration and Heinzpeter Schwermer for generating the map in figure 1. This study was funded by the Swiss Federal Veterinary Office and the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors' contributions

UL performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. GR participated in the study design, coordinated the collaboration with the cantonal laboratories and supervised data analysis. RS was responsible for isolation and susceptibility testing of Campylobacter species. JD and BB participated in the design of the study. JD initiated the collaboration with the cantonal laboratories, and consulted on all practical aspects of sample collection. KS conceived of the project, and provided valuable scientific input during the design, implementation and data analysis phase. All authors read, commented on and approved of the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Ledergerber, U., Regula, G., Stephan, R. et al. Risk factors for antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter spp. isolated from raw poultry meat in Switzerland. BMC Public Health 3, 39 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-3-39

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-3-39