Abstract

Background

Drosophila mojavensis has been a model system for genetic studies of ecological adaptation and speciation. However, despite its use for over half a century, no linkage map has been produced for this species or its close relatives.

Results

We have developed and mapped 90 microsatellites in D. mojavensis, and we present a detailed recombinational linkage map of 34 of these microsatellites. A slight excess of repetitive sequence was observed on the X-chromosome relative to the autosomes, and the linkage groups have a greater recombinational length than the homologous D. melanogaster chromosome arms. We also confirmed the conservation of Muller's elements in 23 sequences between D. melanogaster and D. mojavensis.

Conclusions

The microsatellite primer sequences and localizations are presented here and made available to the public. This map will facilitate future quantitative trait locus mapping studies of phenotypes involved in adaptation or reproductive isolation using this species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Evolutionary biologists have struggled to determine the number and types of genetic changes that lead to speciation. Recent advances in molecular techniques facilitate a more thorough investigation into these issues. For example, by mapping quantitative trait loci (QTLs) affecting interesting traits, we can explore the genetic basis of phenotypic variation between two populations that may lead to reproductive isolation.

One hallmark species used in studies of speciation and ecological adaptation is the desert cactophilic Drosophila mojavensis. D. mojavensis belongs to the mulleri complex of the repleta species group within the subgenus Drosophila. Unlike many well-studied Drosophila, its ecological niche has been well documented, and extensive cytogenetic work has been done on it and its close relative, D. arizonae [see e.g., [1]]. With regard to speciation, D. mojavensis has been the subject of many genetic and phenotypic studies of mate choice [e.g., [2–5]], hybrid sterility and inviability [6, 7], and variation in sperm and female sperm-storage organ length [8, 9]. However, all of these studies have been forced to use a handful of either allozyme or morphological mutant markers. Microsatellites have been isolated from this species before [10], but they are unmapped and their sequences are not available.

Here, we present a microsatellite-based linkage map of the five major chromosomes of D. mojavensis using a new set of markers. We mapped 25 microsatellites to the X chromosome and 65 microsatellites spanning the four major autosomes. We also use our results to confirm the conservation of Muller's chromosome elements [11] across approximately 65 million years of evolutionary divergence between D. melanogaster and D. mojavensis [see [12]]. Muller [11] had suggested that chromosomal elements conserve their identities (ie, complement of genes) across all Drosophila species, and several subsequent studies have supported this idea [e.g., [13–15]], though only one study involving the repleta group [16].

Results and Discussion

Primers were successfully developed for a total of 116 markers. Of these, 26 did not distinguish between the two isofemale lines that were used for mapping and were therefore not pursued. We mapped 25 microsatellites onto the X-chromosome, 10 onto chromosome 2, 7 onto chromosome 3, 13 onto chromosome 4, and 10 onto chromosome 5. Twenty-five more microsatellites were confirmed to be autosomal but could not be mapped because of segregating polymorphism within our lines. Microsatellites were named based on their localizations, where the fifth character of the name was an X if X-linked, A if unmapped autosomal, or a number indicating a specific autosome. The distribution of microsatellites across the chromosomes suggests a possible excess of repetitive sequences on the X-chromosome (27.8% observed vs. 20% expected assuming all chromosomes are similar in size, chi-square test, p = 0.07; 27.8% observed vs. 18.7% expected assuming chromosomes are the same size as D. melanogaster homologous chromosome arms, chi-square test, p = 0.03).

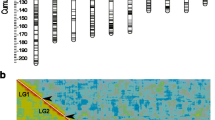

Using two female-parent backcrosses, we constructed a recombinational map of the Drosophila mojavensis genome using 34 of our microsatellites: 13 on the X-chromosome, 7 on chromosome 2, 4 on chromosome 3, 7 on chromosome 4, and 3 on chromosome 5. Recombinational distances are presented in Figure 1. DMOJX040 was not placed in the figure because it was only 0.7 cM from DMOJX030. The recombinational lengths of the chromosomes generally exceed the homologous chromosome arms in D. melanogaster and some other Drosophila species. For example, the X-chromosome in D. mojavensis spanned 130.8 cM, while the X-chromosome in D. melanogaster spans only 73 cM. Even within the repleta species group, D. buzzatii has an X-chromosome that spans 109 cM [17] and D. hydei's X spans 116 cM [12]. Similarly, D. mojavensis chromosome 2 could only be assembled into three pieces that recombine freely from each other. This difference between species in recombinational length most likely indicates an overall greater recombination rate per megabase in D. mojavensis, but we cannot exclude dramatic differences in sequence lengths of the chromosome arms.

Linkage map of the five major chromosomes of Drosophila mojavensis. From left to right, are the X-chromosome, chromosome 2, chromosome 3, chromosome 4, and chromosome 5. Kosambi recombinational distances between markers are on the left of each chromosome, and the microsatellite names are on the right. A question mark appears between markers or groups when markers were assigned to the same chromosomes but freely recombined from each other.

We recombinationally mapped some markers in a second cross because of segregating variation within the lines. Figure 1 presents the most conservative map, where all markers were mapped against each other for any particular chromosome. However, we have some additional information about the linkage of other microsatellites. Specifically, we observed that DMOJ4200 is freely recombining from all the 4-chromosome markers between and including DMOJ4010 and DMOJ4060. Also, the following markers are freely recombining from each other on chromosome 5: DMOJ5100, DMOJ5200, DMOJ5300, and DMOJ5400.

To evaluate the conservation of Muller's elements across 65 million years, we used BLAST [18] to identify segments homologous to the sequences flanking the 65 microsatellites in D. mojavensis that were mapped to chromosome. We identified segments mapped to D. melanogaster chromosomes similar to 23 of the sequences isolated from D. mojavensis (see Table 1). The inferred homology of the arms are as follows (melanogaster:mojavensis): X:X, 2L:3, 2R:5, 3L:4, 3R:2 [19, 20]. Based on the BLAST results, all 23 D. mojavensis sequences matched D. melanogaster sequences on the homologous chromosome arms. This observation strongly supports the conservation of Muller's elements between the subgenera Drosophila (D. mojavensis) and Sophophora (D. melanogaster).

Conclusions

We have developed and mapped a panel of 90 variable microsatellites for genetic studies in a model system for ecological genetics and speciation: Drosophila mojavensis. Thirty-four of these microsatellites have been placed onto a detailed linkage map of this species. We also confirmed that Muller's chromosome elements were conserved between D. melanogaster and D. mojavensis, species separated by 65 million years of independent evolution, in 23 of 65 sequences tested. Given the long-term interest in this species for studies of adaptation and speciation, the construction of a linkage map and presentation of variable microsatellite sequences will facilitate future work in this area.

Methods

Isolation of microsatellite sequences

We used a modification of Hamilton et al's [21] enrichment technique to increase the proportion of microsatellites in the genomic DNA insert library prior to cloning [see also [22]]. This procedure uses a subtractive hybridization, in which streptavidin-coated magnetic beads and biotinylated oligonucleotide repeats retain single-stranded genomic DNA fragments containing repeat sequences.

Genomic DNA was isolated from approximately 30 D. mojavensis individuals from a mixture of strains using the Puregene™ DNA Isolation Kit (Gentra Systems). Except where indicated, we used reagent concentrations and reaction conditions suggested by Hamilton et al [21]. The enrichment procedure was repeated seven times. For each enrichment, one of the following enzymes was used with Nhe I to digest Drosophila mojavensis genomic DNA: Sau 3AI, Bfuc I, Rsa I, Alu I, or HpyCH4 III. Linker sequences were ligated to the digested DNA to provide a PCR priming site. We then hybridized the digested, linker-ligated DNA to a biotinylated oligonucleotide repeat motif, either (CA)15 or (AG)15, and recovered the microsatellite-enriched DNA. The DNA was amplified via PCR, and fragments between 300 and 800 bp were recovered from an agarose gel for cloning. We then used the Invitrogen TOPO-TA cloning kit to clone the DNA into plasmids and transform into E. coli. We omitted the chemiluminescent screen and used pUC19 primers to amplify D. mojavensis DNA inserts directly from colonies. Each 50 μl reaction volume contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 20 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM each dNTP, 0.5 μM pUC forward and reverse primers, and 1.0 unit Taq polymerase (AmpliTaq, Perkin Elmer). DNA was added by touching a sterile toothpick to a colony and swirling the toothpick into the reaction mix. We used the following thermal profile: 95°C for 5 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 60 s; 55°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s; rapid thermal ramp to 40°C. PCR products were sequenced with an ABIPrism® Big Dye™ Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit, and products were visualized on ABI sequencers in the LSU Museum of Natural Science, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, or the Department of Biological Sciences' genomics facility.

Fly stocks

Several inbred lines of D. mojavensis were tested to determine the most suitable lines for constructing a microsatellite map based on microsatellite allelic differences between strains, bearing the same chromosomal arrangements, and lack of segregating microsatellite alleles. In the end, we selected the lines A993 (Rancho El Diamante, Sonora) and A924 (St. Rosa Mtns., AZ), obtained from Dr. William J. Etges. These lines were further brother-sister mated for 9–12 generations to ensure thorough inbreeding and a reduction of segregating alleles.

Microsatellite assay conditions

We designed two primers for each microsatellite-bearing sequence, one bearing an M13(-29) tail. A 10 μL PCR reaction was then performed using 0.5 μM of each primer, 1.0 μL of dNTPs, 1.0 μL of 10X PCR buffer (100 mM Tris pH 8.3, 500 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2), 0.4 μL of IRDye (LiCor), 1U Taq DNA polymerase, and 0.5 μL from a single fly DNA preparation (Puregene). We sometimes added 1.0 μL of 10 mM MgCl2 to the reaction or more polymerase to optimize the results of the PCR. A touchdown PCR cycle was performed [23], and amplifications were visualized on acrylamide gels on our LiCor DNA analyzer.

Assignment to linkage groups

Virgin females and males of the A993 and A924 lines were crossed and offspring reared. DNA was isolated from the parents and progeny using the Puregene™ DNA Isolation Kit (Gentra Systems). We determined if markers differentiating the lines were X-linked or autosomal by comparing the F1 males to the F1 females and parent strains. For X-linked markers, males consistently bore one allele while females consistently bore two. Autosomal markers were further tested using 20 progeny of a male-parent backcross. Because there is no recombination in Drosophila males, the offspring all inherited a nonrecombinant chromosome from one of the original lines. By comparing genotypes across the male-parent backcross progeny, markers were assigned to linkage groups. We also used the NCBI Basic Local Alignment Search Tool [BLAST: [18]] to identify putatively homologous sequences in D. melanogaster. Sequences bearing an expect (E) value below 0.01 were scored, as E-values are nearly identical to probability (p) values in that range.

Recombinational mapping within linkage groups

Virgin F1 females (progeny of the cross described in "Assigning to linkage groups") were backcrossed to males of one of the pure lines (A924). To ascertain the recombinational distances between the markers on each chromosome, we genotyped the parents and 200 progeny with each marker previously assigned to a linkage group. Recombinational distances were estimated in Kosambi centiMorgans using Mapmaker [24].

References

Ruiz A, Heed WB, Wasserman M: Evolution of the mojavensis cluster of cactophilic Drosophila with descriptions of two new species. J Hered. 1990, 81: 30-42.

Etges WJ: Premating isolation is determined by larval substrates in cactophilic Drosophila mojavensis. Evolution. 1992, 46: 1945-1950.

Zouros E: The chromosomal basis of sexual isolation in two sibling species of Drosophila: D. arizonensis and D. mojavensis. Genetics. 1981, 97: 703-718.

Wasserman M, Koepfer HR: Character displacement for sexual isolation between Drosophila mojavensis and Drosophila arizonensis. Evolution. 1977, 31: 812-823.

Etges WJ, Ahrens MA: Premating isolation Is determined by larval-rearing substrates in cactophilic Drosophila mojavensis. V. Deep geographic variation in epicuticular hydrocarbons among isolated populations. Am Nat. 2001, 158: 585-598. 10.1086/323587.

Zouros E: The chromosomal basis of viability in interspecific hybrids between Drosophila arizonensis and Drosophila mojavensis. Can J Genet Cytol. 1981, 23: 65-72.

Pantazidis AC, Galanopoulos VK, Zouros E: An autosomal factor from Drosophila arizonae restores spermatogenesis in Drosophila mojavensis males carrying the D. arizonae Y chromosome. Genetics. 1993, 134: 309-318.

Miller GT, Starmer WT, Pitnick S: Quantitative genetic analysis of among-population variation in sperm and female sperm-storage organ length in Drosophila mojavensis. Genet Res Camb. 2003, 81: 213-220. 10.1017/S0016672303006190.

Pitnick S, Miller GT, Schneider K, Markow TA: Ejaculate-female coevolution in Drosophila mojavensis. Proc Roy Soc Lond B. 2003, 270: 1507-1512. 10.1098/rspb.2003.2382.

Ross CL, Dyer KA, Erez T, Miller SJ, Jaenike J, Markow TA: Rapid divergence of microsatellite abundance among species of Drosophila. Mol Biol Evol. 2003, 20: 1143-1157. 10.1093/molbev/msg137.

Muller HJ: Bearings of the Drosophila work on systematics. In New Systematics. Edited by: Huxley J. 1940, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 185-268.

Powell JR: Progress and Prospects in Evolutionary Biology: The Drosophila Model. New York: Oxford University Press. 1997

Whiting JH, Pliley MD, Farmer JL, Jeffery DE: In situ hybridization analysis of chromosomal homologies in Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila virilis. Genetics. 1989, 122: 99-109.

Papaceit M, Juan E: Chromosomal homologies between Drosophila lebanonensis and D. melanogaster determined by in situ hybridization. Chromosoma. 1993, 102: 361-368. 10.1007/BF00661280.

Gallego P, Juan E, Papaceit M: Chromosomal homologies between Drosophila melanogaster and D. funebris determined by in-situ hybridization. Chromosome Res. 1999, 7: 331-339. 10.1023/A:1009207812569.

Ranz JM, Segarra C, Ruiz A: Chromosomal homology and molecular organization of Muller's elements D and E in the Drosophila repleta species group. Genetics. 1997, 145: 281-295.

Schafer DJ, Fredline DK, Knibb WR, Green MM, Barker JSF: Genetics and linkage mapping of Drosophila buzzatii. J Hered. 1993, 84: 188-194.

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ: Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990, 215: 403-410. 10.1006/jmbi.1990.9999.

Wasserman M: Evolution of the repleta group. In The Genetics and Biology of Drosophila. 3b. Edited by: Ashburner M, Carson HL, Thompson JN. 1982, London: Academic Press, 61-139.

Wasserman M: Cytological evolution of the Drosophila repleta species group. In Drosophila Inversion Polymorphism. Edited by: Krimbas CB, Powell JR. 1992, Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 455-552.

Hamilton MB, Pincus EL, DiFiore A, Fleischer RC: Universal linker and ligation procedures for construction of genomic DNA libraries enriched for microsatellites. BioTechniques. 1999, 27: 500-507.

Kandpal RP, Kandpal G, Weissman SM: Construction of libraries enriched for sequence repeats and jumping clones, and hybridization selection for region-specific arkers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994, 91: 88-92.

Palumbi SR: Nucleic Acids II: The Polymerase Chain Reaction. In Molecular Systematics. Edited by: Hillis DM, Moritz C, Mable BK. 1996, Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer Associates, Inc, 205-247.

Lander ES, Green P, Abrahamson J, Barlow A, Daly MJ, Lincoln SE, Newburg L: MAPMAKER: An interactive computer package for constructing primary genetic linkage maps of experimental and natural populations. Genomics. 1987, 1: 174-181. 10.1016/0888-7543(87)90010-3.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Science Foundation grants 9980797, 0211007, and 0314552, and Louisiana Board of Regents Governor's Biotechnology Initiative grant 005 to MAFN and a Sigma Xi grant-in-aid of research to SDS. We thank William J. Etges for providing fly stocks and moral support, Daniel Ortiz-Barrientos, Christy Henzler, and three referees for constructive comments on this manuscript, and Lisa Burk for technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

RS maintained all fly cultures and performed all reactions and analyses involved in the recombinational mapping of microsatellites. SDS and MAFN produced the microsatellite genomic libraries, sequenced the clones, and designed the primers. All authors contributed to the preparation of this manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Staten, R., Schully, S.D. & Noor, M.A. A microsatellite linkage map of Drosophila mojavensis. BMC Genet 5, 12 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2156-5-12

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2156-5-12