Abstract

Background

Interspecific variation in avian colour vision falls into two discrete classes: violet sensitive (VS) and ultraviolet sensitive (UVS). They are characterised by the spectral sensitivity of the most shortwave sensitive of the four single cones, the SWS1, which is seemingly under direct control of as little as one amino acid substitution in the cone opsin protein. Changes in spectral sensitivity of the SWS1 are ecologically important, as they affect the abilities of birds to accurately assess potential mates, find food and minimise visibility of social signals to predators. Still, available data have indicated that shifts between classes are rare, with only four to five independent acquisitions of UV sensitivity in avian evolution.

Results

We have classified a large sample of passeriform species as VS or UVS from genomic DNA and mapped the evolution of this character on a passerine phylogeny inferred from published molecular sequence data. Sequencing a small gene fragment has allowed us to trace the trait changing from one stable state to another through the radiation of the passeriform birds. Their ancestor is hypothesised to be UVS. In the subsequent radiation, colour vision changed between UVS and VS at least eight times.

Conclusions

The phylogenetic distribution of SWS1 cone opsin types in Passeriformes reveals a much higher degree of complexity in avian colour vision evolution than what was previously indicated from the limited data available. Clades with variation in the colour vision system are nested among clades with a seemingly stable VS or UVS state, providing a rare opportunity to understand how an ecologically important trait under simple genetic control may co-evolve with, and be stabilised by, associated traits in a character complex.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Colour perception is one of the disciplines where birds excel. In general, interspecific variation in avian colour vision falls into two discrete classes, which are characterised by the spectral sensitivity of the most shortwave sensitive of the four single cones, the SWS1 [1] (the other, more long-wave sensitive being SWS2, MWS and LWS). The wavelength of maximum sensitivity (λmax) of the SWS1 ranges either from 355-380 nm in the 'ultraviolet sensitive' class (UVS) or from 402-426 nm in the 'violet sensitive' (VS) (reviewed by [2] and [3]). The UVS class is optimised for ultraviolet sensitivity, but the VS class also has some degree of sensitivity in the ultraviolet spectrum (Figure 1). Changes in spectral sensitivity of the SWS1 are ecologically important, as spectral tuning affects the abilities of birds to accurately assess the quality of potential mates [4–14], spot elusive prey or detect other food items [15–20] and minimise visibility of social signals in plumage coloration to predators [21].

Examples of spectral sensitivities for VS and UVS birds. Normalised single cone spectral sensitivities (from left to right: SWS1, SWS2, MWS and LWS) of a VS bird (Indian Peafowl Pavo cristatus) [68] and a UVS bird (Eurasian Blue Tit Cyanistes caeruleus) [36] including the effects of ocular medium absorption. Human visible range is approximately 400-700 nm, with wavelengths shorter than 400 nm being ultraviolet.

Non-conservative substitutions in the SWS1 cone opsin protein that are located in the retinal binding pocket close enough to interact with the retinal chromophore may shift λmax from UVS to VS or vice versa [22, 23]. Replacement of cysteine by serine in the 90th amino acid (aa) position, the substitution Cys90Ser, or the reverse substitution, alone accounts for the whole shift (all aa residues named in this article are numbered according to bovine rhodopsin ([24]). Despite the simple nature of the mechanism, very few shifts have been described so far (e.g. review in [2]), suggesting that the SWS1 cone spectral sensitivity is under strong stabilising selection. The VS class is both ancestral and the most common to birds; its members are distributed throughout the avian phylogeny [25, 26]. Four or five independent shifts to UVS are currently known: in shorebirds, Passerida passerines, parrots, the rhea and presumably trogons [[26] and references therein, [27–30]].

The most promising group of birds for further investigation into the spectral tuning of SWS1 cone opsins is clearly the passerines (Passeriformes). This is the most species rich of all avian orders and the only one except the shorebirds (Charadriiformes) from which both classes of spectral sensitivity are known. Every investigated member of the Passerida clade of passerines belongs to the UVS class [26, 27, 31–38] and it has appeared that all other passerines can be placed in the VS category (see [26, 27, 37, 39] and Browne, et al. 2006 (GenBank only)). Recently, however, Ödeen et al. [40] argued that the evolution of ultraviolet sensitive vision in Passeriformes is more complex than a single VS to UVS opsin shift in an ancestor of Passerida, presenting molecular evidence for additional UV shifts from VS colour vision outside Passerida, in fairywrens, genus Malurus.

Since spectral tuning of the cone is under the genetic control of a few amino acid residues in the opsin protein, it is possible to quickly classify almost any bird as VS or UVS from a sample of genomic DNA [3, 26]. The accuracy of this short-fragment genomic DNA approach in distinguishing UVS from VS species has been validated against all published MSP data [3]. We have employed this method to search for gross differences in spectral tuning in a larger sample of passerine species than has been investigated before. Our aims with this survey were to assess how stable SWS1 cone sensitivity has been in the course of passerine evolution and to trace the evolutionary sequence of shifts in spectral tuning. As the basis for the study, we have inferred a molecular phylogeny with sequence data from GenBank.

Results

Opsin sequencing

We amplified the target fragment of the SWS1 opsin gene in 56 passerine species from 30 families and one falconiform species, Northern Crested Caracara Caracara cheriway (Additional file 1). Cycle sequencing produced 50-107 bp long overlapping strands of identifiable nucleotides. Sequences have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) (accession numbers in Additional file 1). Amino acid translations spanning the spectral tuning sites 86, 90 and 93 [22] are presented in Additional file 1. For unknown reasons, we failed to amplify the SWS1 opsin in two species: Blue Jewel-babbler Ptilorrhoa caerulescens (Psophodidae) and White-bellied Erpornis Erpornis zantholeuca (Vireonidae).

Position 90 held either serine or cysteine residues, signifying VS and UVS opsins, respectively. Neither phenylalanine nor any other aa residues suggesting a potential major shift in spectral tuning through a non-conservative substitution was present at site 86 (cf. [28]). However, the Rifleman Acanthisitta chloris holds leucine in spectral tuning site 93 (Leu93). This state is previously undescribed in birds and probably the result of a non-conservative substitution (see below).

Phylogenetic reconstruction

The inferred tree (Figure 2) is mostly well resolved and, except for some short internal branches, well supported. It agrees well with previously published passerine trees based on fewer loci, such as a large-scale study of passerine relationships based on RAG-1 and -2 [41], as well as with more densely sampled studies of the Passerida based on ODC, myo and β-fibrinogen intron 5 [42] and of the 'core Corvoidea' based on ODC, myo, RAG-1 and -2, and ND2 [43].

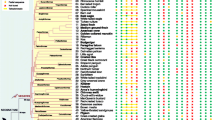

Phylogenetic recontruction of SWS1 opsin evolution. Majority rule (50%) consensus tree of passerines based on concatenated mitochondrial cytochrome b and ND2, nuclear myoglobin intron 2, ODC introns 6 to 7, TGFβ2 intron 5, and protein-coding nuclear c-myc exon 3, RAG-1 and RAG-2 sequences (> 9 kbp), inferred by Bayesian inference, analysed in eight partitions, with two parrots and two falconiforms as outgroup. Posterior probabilities given at nodes, * indicating ≥0.95. Long Ailuroedus branch truncated. VS/UVS optimisation represented by violet for VS, black for UVS and dotted for ambiguous. Transitions from one state to another are indicated by numbers; 1a and 1b, and 2a and 2b, respectively, represent uncertainties due to ambiguous ancestral state. a, b and c refer to insignificantly supported nodes discussed in the text. # Sister clade, genus Malurus (not included), contains both VS and UVS species [40].

The character optimisation infers a minimum of six changes, two from VS to UVS, two from UVS to VS and two with uncertain direction due to three nodes with ambiguous ancestral states near the root (Figure 2). The number of inferred transitions are reduced to five, if clades b and c in Figure 2, which are reconstructed with low support, are collapsed, and Cnemophilus is placed as sister to the 'core Corvoidea' clade (Additional file 2). On the contrary, if all 'basal' nodes with posterior probability < 0.95 are collapsed, eight transitions are inferred (Additional file 3). The ancestor to all passerines is reconstructed as UVS when only parrots (UVS) form the outgroup, whereas it is ambiguous when falconiforms (VS) are also included in the outgroup (as shown in Figure 2).

Discussion

The evolution of colour vision in birds has apparently involved many more than the four to five independent shifts between SWS1 cone opsin types that previously available data have indicated. In Passeriformes, the picture is indeed more complex than a single VS to UVS opsin shift in an ancestor of Passerida; our phylogenetic trait mapping reveals more variation among the passerines than what is known from other birds combined. The class of colour vision of the most recent common ancestor to the passerines is ambiguous as a result of different states in parrots (UVS) and falconiforms (VS). As parrots are suggested to be the sister group to the passerines [44], the passerine ancestor is hypothesised to be UVS (as inferred when falconiforms are excluded from the optimisation analyses). In the subsequent passerine radiation, colour vision has changed between UVS and VS at least eight times, including two shifts in the family Maluridae (signified by # in Figure 2) [40].

It is interesting to note that two major clades, the Passerida/Petroicidae and the suboscines, are homogeneous with respect to colour vision (albeit different classes), whereas there is considerably more variation in the rest of the tree, particularly within Maluridae. It is not immediately apparent what the selective advantage of either VS or UVS might be, as both classes are present in taxa represented on all continents and in similar habitats. For example, the ancestor to the mostly forest-dwelling New World Vireonidae has changed from VS to UVS, whereas the mainly forest-inhabiting New World suboscines are VS. Moreover, the UVS Passerida/Petroicidae clade is mainly distributed in Afro-Eurasia and the New World, with few representatives in Australasia; the VS suboscines occur predominantly in the New World, with relatively few species in Africa, Madagascar, Asia and Australasia; the mostly VS, but also UVS, 'basalmost' oscines (Menura-Orthonyx) plus Philesturnus, Cnemophilus and Toxorhampus are chiefly Australasian; and the 'core Corvoidea' have representatives on all continents. The ancestral area of the passerines has been inferred to be eastern Gondwana, i.e. proto-Australasia [45, 46], whereas the Philesturnus/Cnemophilus/Toxorhampus/'core Corvoidea' clade has been inferred to have originated in the proto-Papuan archipelago [43].

Unlike Maluridae (represented by Amytornis in Figure 2), none of the multi-sampled families from the present study are polytypic in gross tuning of the SWS1 opsin, but either contain VS or UVS taxa. In common with the Australian-Papuan Maluridae, the African-Eurasian genus Motacilla (wagtails) is rich in species and subspecies with strong differentiation in male plumage coloration. Yet, all the members of Motacilla sampled have base-pair identical SWS1 opsin gene fragments.

Unknown differences in other traits than SWS1 could explain why UVS-VS shifts are so unequally distributed between Passerida/Petroicidae and other passerines. Spectral tuning of the SWS1 cone opsin seems to be under strong stabilising selection in birds [30], likely partly due to gross spectral tuning shifts carrying costs, such as increased retinal photooxidation and ocular light scattering (reviewed in [47]). In addition, acute short wave colour vision is dependent on a complex of co-adapted physiological traits. Ultraviolet absorption by the ocular media is usually stronger in VS than in UVS species (reviewed in [48, 49]), and the SWS2 cone class (sensitive to 'blue', λmax 451-480 nm) is shifted toward shorter wavelengths in UVS than in VS birds (see review in [2]). A shortwave shift in λmax of a VS SWS1 pigment will produce a virtually negligible increase in UV sensitivity, unless it is accompanied by an increased UV transmission in the ocular media [48]. A shortwave shifted SWS1 will cause an uneven distribution of sensitivities across the spectrum, possibly deteriorating colour discriminability, if not followed by a shift of the SWS2 pigment towards the range vacated by SWS1. A plausible evolutionary scenario is that increased UV transmittance in an ancestor of passerines relaxed stabilising selection on SWS1 spectral tuning, allowing a VS to UVS shift of that opsin to reach fixation (see [48]) (the only close relative to passerines studied in this respect is one with a UV transparent ocular media: Budgerigar Melopsittacus undulatus [49]). Later, a shortwave shift in SWS2 spectral tuning in an ancestor of Passerida/Petroicidae may have improved spectral discriminability of UVS retinae and thereby reinstated stabilising selection on SWS1 spectral tuning. In agreement with this scenario, Passerida species where this cone has been examined by MSP mostly show shortwave shifted SWS2 λmax compared to VS species from other avian orders (see review [2]), but unfortunately the character state is not known from any VS or non-Passerida passerine. The realised spectral sensitivities of the two shortwave sensitive cones in non-Passerida passerines may be different from that of characteristic VS and UVS types (cf. review in [2]). Due to a general paucity of data on SWS2 λmax and ocular transmission, one can merely speculate at this point.

Shifts from UVS to VS in passerines seem to be controlled exclusively by the Cys90Ser substitution. Carvalho et al. [28] has reported a significant short wavelength tuning effect of substitution Ser86Phe, but we did not find phenylalanine in position 86 (Phe86) in any of the species we sequenced. The effects of all tuning site substitutions found in this study are known [22, 23], with one exception: a leucine residue in the spectral tuning site 93 of the Rifleman Acanthisitta chloris. The most likely evolutionary event given the phylogeny in Figure 2 is the substitution Thr93Leu. This is a non-conservative substitution, changing from polar and mildly hydrophilic threonine to nonpolar, hydrophobic leucine. Site 93 is located in the retinal binding pocket, on the inner side of the opsin's alpha-helices close enough to interact with the retinal chromophore. Thr93Leu is therefore potentially important to spectral tuning (see [50]), but its effect in the avian SWS1 opsin is presently unknown.

The reconstruction of the evolution of colour vision in passerines is conditional on the true phylogeny having been inferred. The tree inferred here is based on a larger number of loci than any previous study of passerine relationships. As it is overall well supported by the data, and in good agreement with previous analyses of different datasets (e.g. [41–43], it is a well founded hypothesis of relationships. Although the tree has some nodes with low posterior probability, only two of these affect the interpretation of the evolution of colour vision (indicated by a and b in Figure 2). With respect to the poorly supported node a, switching position between Pomatostomus and Orthonyx, as is possible if this node is collapsed, would require one more step in the VS/UVS optimisation and result in eight further internal nodes having ambiguous states. Further collapsing of poorly supported 'basal' nodes leads to more steps in the UV optimisation. Accordingly, the opsin data lend further support to the present topology, and the favoured topology results in a more parsimonious optimisation than the alternative topologies. However, if the insignificantly supported nodes b and c are collapsed, and Cnemophilus is placed as sister to the 'core Corvoidea', one fewer change is required to explain the evolution of colour vision. More sequence data might resolve this issue in the future.

Conclusions

Spectral tuning of the SWS1 cone opsin in birds is a trait of great ecological importance. It appears to be under strong stabilising selection and varies categorically between different clades in the avian phylogenetic tree. In the radiation of the very species rich order Passeriformes, sequencing of a small gene fragment allows us to map and trace the change from one stable state to the other. Clades with variation in the colour vision system are nested among clades with a seemingly stable VS or UVS state, providing a rare opportunity to understand how an ecologically important trait under simple genetic control may co-evolve with, and be stabilised by, associated traits in a character complex.

Methods

Opsin sequencing

We isolated genomic DNA from tissues and blood samples, which we took from live birds in the field or borrowed from museums and colleagues. As far as feasible we included representatives from clades of expected importance to tracing the radiation of passerines. As demonstrated in the fairywren case [40], closely related groups of passerine taxa might be polytypic with respect to spectral tuning of the SWS1 opsin. Acknowledging this possibility, we sampled multiple taxa in selected genera. We used a GeneMole® automated nucleic acid extraction instrument (Mole Genetics) and the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAGEN) for the DNA isolation. Standard procedures were applied. With the same protocol and primers as are described in [3] and [26] we then amplified a fragment of the SWS1 opsin gene, containing the aa residues at positions 81-94, all located in the 2nd α-helical transmembrane region.

We translated the DNA sequences into amino acids to identify the spectral tuning sites 86, 90, and 93 of SWS1 [22, 23]. Then we calculated λmax from the tuning sites following in vitro changes in λmax reported by Wilkie et al. [22]. We assumed the effects of the key tuning sites to be additive. This assumption should provide reasonable approximations of λmax [51], although it disregards potential interactions between the tuning sites (see [52]).

Phylogenetic reconstruction

A phylogeny was inferred from sequences in GenBank (Additional file 4). We made a search in GenBank for all falconiform, psittaciform and passeriform species for which we and others had sequenced the SWS1 opsin gene. We then selected eight loci for which sequences were available for a large proportion of these species or members of the same genus: the mitochondrial cytochrome b (cytb) and NADH dehydrogenase II (ND2) genes, the nuclear myoglobin gene, intron 2 (myo), ornithine decarboxylase gene, introns 6 to 7 (ODC), transforming growth factor beta-2 gene, intron 5 (TGFβ2), and the protein-coding nuclear c-myc exon 3 and recombination-activating protein 1 and 2 genes (RAG-1, RAG-2). Sequences were aligned using the MUSCLE web server http://www.drive5.com/muscle; some manual adjustment was necessary for the non-coding sequences. The alignment is in Additional file 5.

The phylogeny was estimated by Bayesian inference using MrBayes 3.1.2 [53, 54], with the sequences concatenated and partitioned by locus, using rate multipliers to allow different rates for the different partitions [55, 56]. Ambiguous base pairs and indels were treated as missing data. As outgroups, we chose two falconiforms and two parrots, as these have been shown to be closely related to passerines [44, 57]. Appropriate substitution models were determined based on the Bayesian Information Criterion [58] calculated by jModelTest version 0.1.1 [59]. For cytb, ND2 and RAG-1, the best-fit model was the general time-reversible (GTR) model [60–62], assuming rate variation across sites according to a discrete gamma distribution with four rate categories (Γ; [63]) and an estimated proportion of invariant sites (I; [64]) (GTR+Γ+I). For the other loci, the Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano (HKY) model [65] plus Γ was selected (HKY+Γ), with the addition of I for myoglobin and c-myc (HKY+Γ+I). Posterior probabilities (PPs) were calculated in MrBayes using default priors. Four Metropolis-coupled MCMC chains with incremental heating temperature 0.1 were run for 7 × 106 generations and sampled every 1000 generations. Chain likelihood and other parameter values and effective sample sizes (> 200) were inspected in Tracer 1.5.0 [66]. The first 25% of the generations were discarded as 'burn-in', well after stationarity of most chain likelihood values had been established, and the posterior probability was estimated for the remaining generations. The analysis was run eight times, and the topologies and posterior probabilities were compared by eye and by the mean estimates and the corresponding standard errors.

Optimisation of the VS/UVS character was performed by parsimony in MacClade 4.08 [67], using default settings (polytomies treated as soft).

Abbreviations

- λmax:

-

wavelength of maximum absorbance

- MSP:

-

microspectrophotometry

- SWS1:

-

short-wavelength sensitive pigment, type one

- VS:

-

violet sensitive

- UVS:

-

ultraviolet sensitive.

References

Cuthill IC, Partridge JC, Bennett ATD, Church SC, Hart NS, Hunt S: Ultraviolet vision in birds. Adv Stud Behav. 2000, 29: 159-214.

Hart NS, Hunt DM: Avian visual pigments: characteristics, spectral tuning and evolution. Am Nat. 2007, 169 (Supplement): S7-S26.

Ödeen A, Hart NS, Håstad O: Assessing the use of genomic DNA as a predictor of the maximum absorbance wavelength of avian SWS1 opsin visual pigments. J Comp Physiol A. 2009, 195: 167-173. 10.1007/s00359-008-0395-2.

Maier EJ: To deal with ''invisible'': on the biological importance of ultraviolet sensitivity in birds. Naturwissenschaften. 1993, 80: 476-478. 10.1007/BF01136043.

Bennett ATD, Cuthill IC, Partridge JC, Maier EJ: Ultraviolet vision and mate choice in zebra finches. Nature. 1996, 380: 433-435. 10.1038/380433a0.

Bennett ATD, Cuthill IC, Partridge JC, Lunau K: Ultraviolet plumage colors predict mate preferences in starlings. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997, 94: 8618-8621. 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8618.

Andersson S, Amundsen T: Ultraviolet colour vision and ornamentation in bluethroats. Proc R Soc B. 1997, 264: 1587-1591. 10.1098/rspb.1997.0221.

Hunt S, Cuthill IC, Swaddle JP, Bennett ATD: Ultraviolet vision and band colour preferences in female zebra finches, Taeniopygia guttata. Anim Behav. 1997, 54: 1382-1392.

Hunt S, Bennett ATD, Cuthill IC, Griffiths R: Blue tits are ultraviolet tits. Proc R Soc B. 1998, 265: 451-455. 10.1098/rspb.1998.0316.

Hunt S, Cuthill IC, Bennett ATD, Griffiths R: Preferences for ultraviolet partners in the blue tit. Anim Behav. 1999, 58: 809-815. 10.1006/anbe.1999.1214.

Johnsen A, Andersson S, Örnborg J, Lifjeld JT: Ultraviolet plumage ornamentation affects social mate choice and sperm competition in bluethroats (Aves: Luscinia s. svecica): a field experiment. Proc R Soc B. 1998, 265: 1313-1318. 10.1098/rspb.1998.0435.

Andersson S, Örnborg J, Andersson M: Ultraviolet sexual dimorphism and assortative mating in blue tits. Proc R Soc B. 1998, 265: 445-450. 10.1098/rspb.1998.0315.

Siitari H, Honkavaara J, Huhta E, Viitala J: Ultraviolet reflection and female mate choice in the pied flycatcher, Ficedula hypoleuca. Anim Behav. 2002, 63: 97-102. 10.1006/anbe.2001.1870.

Gaibani G, Csermely D, Zampiga E: Ultraviolet reflectance and female mating preferences in the common kestrel (Falco tinnunculus). Canadian J Zool. 2008, 86: 479-483. 10.1139/Z08-020. (5)

Burkhardt D: Birds, berries and UV. Naturwissenschaften. 1982, 69: 153-157. 10.1007/BF00364887.

Viitala J, Korpimäki E, Palokangas P, Koivula M: Attraction of kestrels to vole scent marks visible in ultraviolet light. Nature. 1995, 373: 425-427. 10.1038/373425a0.

Church SC, Bennett ATD, Cuthill IC, Partridge JC: Ultraviolet cues affect the foraging behaviour of blue tits. Proc R Soc B. 1998, 265: 1509-1514. 10.1098/rspb.1998.0465.

Koivula M, Viitala J: Rough-legged buzzards use vole scent marks to assess hunting areas. Avian Biol. 1999, 30: 329-330. 10.2307/3677362.

Siitari H, Honkavaara J, Viitala J: Ultraviolet reflection of berries attracts foraging birds. A laboratory study with redwings (Turdus iliacus) and bilberries (Vaccinium myrtillus). Proc R Soc B. 1999, 266: 2125-2129. 10.1098/rspb.1999.0897.

Probst R, Pavlicev M, Viitala J: UV reflecting vole scent marks attract a passerine: the great grey shrike Lanius excubitor. J Avian Biol. 2002, 33: 437-440. 10.1034/j.1600-048X.2002.02760.x.

Håstad O, Victorsson J, Ödeen A: Differences in color vision make passerines less conspicuous in the eyes of their predators. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005, 102: 6391-6394. 10.1073/pnas.0409228102.

Wilkie SE, Robinson PR, Cronin TW, Poopalasundaram S, Bowmaker JK, Hunt DM: Spectral tuning of avian violet- and ultraviolet-sensitive visual pigments. Biochemistry. 2000, 39: 7895-7901. 10.1021/bi992776m.

Yokoyama S, Radlwimmer FB, Blow NS: Ultraviolet pigments in birds evolved from violet pigments by a single amino acid change. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000, 97: 7366-7371. 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7366.

Nathans J, Hogness DS: Isolation, sequence analysis, and intron-exon arrangement of the gene encoding bovine rhodopsin. Cell. 1983, 34: 807-814. 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90537-8.

Yokoyama S: Molecular evolution of color vision in vertebrates. Gene. 2002, 300: 69-78. 10.1016/S0378-1119(02)00845-4.

Ödeen A, Håstad O: Complex distribution of avian color vision systems revealed by sequencing the SWS1 opsin from total DNA. Mol Biol Evol. 2003, 20: 855-861. 10.1093/molbev/msg108.

Ödeen A, Håstad O: Pollinating birds differ in spectral sensitivity. J Comp Physiol A. 2010, 196: 91-96. 10.1007/s00359-009-0474-z.

Carvalho LS, Cowing JA, Wilkie SE, Bowmaker JK, Hunt DM: The molecular evolution of avian ultraviolet- and violet-sensitive visual pigments. Mol Biol Evol. 2007, 24: 1843-1852. 10.1093/molbev/msm109.

Carvalho LS, Knott B, Berg ML, Bennett ATD, Hunt DM: Ultraviolet-sensitive vision in long-lived birds. Proc R Soc B. 2010, published online before print July 28

Ödeen A, Håstad O, Alström P: Evolution of ultraviolet vision in shorebirds (Charadriiformes). Biol Lett. 2010, 6: 370-374. 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0877.

Maier EJ, Bowmaker JK: Colour vision in the passeriform bird, Leothrix lutea: correlation of visual pigment absorbance and oil droplet transmission with spectral sensitivity. J Comp Physiol A. 1993, 172: 295-301. 10.1007/BF00216611.

Bowmaker JK, Heath LA, Wilkie SE, Hunt DM: Visual pigments and oil droplets from six classes of photoreceptor in the retinas of birds. Vision Res. 1997, 37: 2183-2194. 10.1016/S0042-6989(97)00026-6.

Hart NS, Partridge JC, Cuthill IC: Visual pigments, oil droplets and cone photoreceptor distribution in the European starling (Sturnus vulgaris). J Exp Biol. 1998, 201: 1433-1446.

Das D, Wilkie SE, Hunt DM, Bowmaker JK: Visual pigments and oil droplets in the retina of a passerine bird, the canary Serinus canaria: microspectrophotometry and opsin sequences. Vision Res. 1999, 39: 2801-2815. 10.1016/S0042-6989(99)00023-1.

Hart NS, Partridge JC, Bennett ATD, Cuthill IC: Visual pigments, cone oil droplets and ocular media in four species of estrildid finch. J Comp Physiol A. 2000, 186: 681-694. 10.1007/s003590000121.

Hart NS, Partridge JC, Cuthill IC, Bennett ATD: Visual pigments, oil droplets, ocular media and cone photoreceptor distribution in two species of passerine bird: the blue tit (Parus caeruleus L.) and the blackbird (Turdus merula L.). J Comp Physiol A. 2000, 186: 375-387. 10.1007/s003590050437.

Ödeen A, Håstad O: New primers for the avian SWS1 pigment opsin gene reveal new amino acid configurations in spectral sensitivity tuning sites. J Hered. 2009, 100: 784-789. 10.1093/jhered/esp060.

Beason RC, Loew ER: Visual pigment and oil droplet characteristics of the bobolink (Dolichonyx oryzivorus), a new world migratory bird. Vision Res. 2008, 48: 1-8. 10.1016/j.visres.2007.10.006.

Seddon N, Tobias JA, Eaton M, Ödeen A: Human vision can provide a valid proxy for avian perception of sexual dichromatism. Auk. 2010, 127: 283-292. 10.1525/auk.2009.09070.

Ödeen A, Pruett-Jones S, Driskell AC, Armenta JK, Håstad O: Multiple shifts between violet and ultraviolet vision in a family of passerine birds with associated changes in plumage coloration. Proc R Soc B. 2011, published online before print October 5

Barker FK, Cibois A, Schikler P, Feinstein J, Cracraft J: Phylogeny and diversification of the largest avian radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004, 101: 11040-11045. 10.1073/pnas.0401892101.

Johansson U, Fjeldså J, Bowie RCK: Phylogenetic relationships within Passerida (Aves: Passeriformes): a review and a new molecular phylogeny based on three nuclear intron markers. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2008, 48: 858-876. 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.05.029.

Jønsson KA, Fabre P-H, Ricklefs RE, Fjeldså J: Major global radiation of corvoid birds originated in the proto-Papuan archipelago. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011, 108: 2328-2333. 10.1073/pnas.1018956108.

Hackett SJ, Kimball RT, Reddy S, Bowie RCK, Braun EL, Braun MJ, Chojnowski JL, Cox WA, Han K-L, Harshman J, Huddleston CJ, Marks BD, Miglia KJ, Moore WS, Sheldon FH, Steadman DW, Witt CC, Yuri T: A phylogenomic study of birds reveals their evolutionary history. Science. 2008, 320: 1763-1768. 10.1126/science.1157704.

Barker FK, Barrowclough GF, Groth JG: A phylogenetic hypothesis for passerine birds: taxonomic and biogeographic implications of an analysis of nuclear DNA sequence data. Proc R Soc B. 2002, 269: 295-308. 10.1098/rspb.2001.1883.

Ericson PGP, Christidis L, Cooper A, Irestedt M, Jackson J, Johansson US, Norman JA: A Gondwanan origin of passerine birds supported by DNA sequences of the endemic New Zealand wrens. Proc R Soc B. 2002, 269: 235-241. 10.1098/rspb.2001.1877.

Bennett ATD, Cuthill IC: Ultraviolet vision in birds: what is its function?. Vision Res. 1994, 34: 1471-1478. 10.1016/0042-6989(94)90149-X.

Håstad O, Partridge JC, Ödeen A: Ultraviolet photopigment sensitivity and ocular media transmittance in gulls, with an evolutionary perspective. J Comp Physiol A. 2009, 195: 585-590. 10.1007/s00359-009-0433-8.

Lind O, Kelber A: Avian colour vison: Effects of variation in receptor sensitivity and noise data on model predictions as compared to behavioural results. Vision Res. 2009, 49: 1939-1947. 10.1016/j.visres.2009.05.003.

Wilkie SE, Vissers PMAM, Das D, DeGrip WJ, Bowmaker JK, Hunt DM: The molecular basis for UV vision in birds: spectral characteristics, cDNA sequence and retinal localization of the UV-sensitive visual pigment of the budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus). Biochem J. 1998, 330: 541-547.

Yokoyama S, Tada T: The spectral tuning in the short wavelength-sensitive type 2 pigments. Gene. 2003, 306: 91-98.

Shi Y, Radlwimmer FB, Yokoyama S: Molecular genetics and the evolution of ultraviolet vision in vertebrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001, 98: 11731-6. 10.1073/pnas.201257398.

Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F: MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogeny. Bioinformatics. 2001, 17: 754-755. 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754.

Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F: MRBAYES version 3.1.2. 2005, [http://mrbayes.scs.fsu.edu/download.php]

Nylander JAA, Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP, Nieves-Aldrey JL: Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of combined data. Syst Biol. 2004, 53: 47-67. 10.1080/10635150490264699.

Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP: MRBAYES 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003, 19: 1572-1574. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180.

Ericson PGP, Anderson CL, Britton T, Elzanowski A, Johansson US, Källersjö M, Ohlson JI, Parsons TJ, Zuccon D, Mayr G: Diversification of Neoaves: integration of molecular sequence data and fossils. Biol Lett. 2006, 2: 543-547. 10.1098/rsbl.2006.0523.

Schwarz G: Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat. 1978, 6: 461-464. 10.1214/aos/1176344136.

Posada D: jModelTest: Phylogenetic Model Averaging. Mol Biol Evol. 2008, 25: 1253-1256. 10.1093/molbev/msn083.

Lanave C, Preparata C, Saccone C, Serio G: A new method for calculating evolutionary substitution rates. J Mol Evol. 1984, 20: 86-93. 10.1007/BF02101990.

Tavaré S: Some probabilistic and statistical problems on the analysis of DNA sequences. Lect Mater Life Sci. 1986, 17: 57-86.

Rodríguez J, Oliver L, Marín A, Medina R: The general stochastic model of nucleotide substitution. J Theor Biol. 1990, 142: 485-501. 10.1016/S0022-5193(05)80104-3.

Yang Z: Maximum likelihood phylogenetic estimation from DNA sequences with variable rates over sites: approximate methods. J Mol Evol. 1994, 39: 306-314. 10.1007/BF00160154.

Gu X, Fu Y-X, Li W-H: Maximum likelihood estimation of the heterogeneity of substitution rate among nucleotide sites. Mol Biol Evol. 1995, 12: 546-557.

Hasegawa M, Kishino H, Yano T: Dating of the human-ape splitting by a molecular clock of mitochondrial DNA. J Mol Evol. 1985, 22: 160-174. 10.1007/BF02101694.

Rambaut A, Drummond AJ: Tracer version 1.5.0. 2009, [http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk]

Maddison WP, Maddison DR: MacClade: Analysis of phylogeny and character evolution. Version 4. 2005, Sunderland, Massachusetts, Sinauer Associates

Hart NS: Vision in the peafowl (Aves: Pavo cristatus). J Exp Biol. 2002, 205: 3925-3935.

Gill F, Donsker D, (eds): IOC World Bird Names (version 2.9). 2011, Accessed Aug. 23 2011, [http://www.worldbirdnames.org/]

Acknowledgements

Tissue samples used for this study were kindly put at our disposal by The Australian Museum, Sydney, Nicklas Backström and Sofia Berlin at the Department of Evolutionary Biology, Allan Baker and Oliver Haddrath at the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Peter Halvarsson at the Department of Population Biology, and Christer Hemborg, Damian Dowling and Anna Qvarnström at the Department of Animal Ecology, Uppsala University, Przemek Chylarecki, The Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Fyris Zoo, Uppsala, Louisiana State University Museum of Natural Science, Baton Rouge, the Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm, Jürgen Tomiuk, University of Washington Burke Museum, Seattle and the Zoological Museum of the University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen. Christer Hemborg, Anders Lindström, Marta Vila Taboada, Teet Sirotkin, Staffan Ulfstrand and Malcom Wilson collected samples in the field together with AÖ. This work was funded by the Swedish Research Council Formas, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, Stiftelsen för zoologisk forskning and Carl Tryggers Stiftelse för Vetenskaplig Forskning.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

AÖ compiled the tissue material and carried out the genetic studies. AÖ and OH conceived of the study, interpreted the opsin results and compiled most of the molecular marker data. PA compiled some of the molecular marker data, performed sequence alignment and reconstructed the phylogeny. All authors participated in the trait state mapping, drafted the manuscript, and read and approved it.

Electronic supplementary material

12862_2011_1914_MOESM1_ESM.DOCX

Additional file 1: SWS1 opsin aa sequences and accession numbers. SWS1 opsin amino acid (aa) sequences from passerine plus falconiform and psittaciform species analysed in the present study and previously. The spectral tuning aa sites 86, 90 and 93 (see text) are marked in bold, as are the ENA accession number of sequences new to this study. Type of SWS1 opsin is estimated from the tuning sites as either VS (violet sensitive) or UVS (UV-sensitive). The taxonomy follows the IOC World Bird List [69]. Numbers after species names signify the number of individuals sequenced. Information on geographic location for the new samples is available at ENA http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/data/view/< ACCESSION NUMBERS HE601811-HE601869 >. (DOCX 71 KB)

12862_2011_1914_MOESM2_ESM.PDF

Additional file 2: Alternative recontruction of SWS1 opsin evolution, 1. Same tree as in Figure 2, but with clades b and c, which are reconstructed with low support, collapsed, and Cnemophilus placed as sister to the 'core Corvoidea' clade. VS/UVS optimisation represented by yellow for VS, blue for UVS, and barred for ambiguous. (PDF 359 KB)

12862_2011_1914_MOESM3_ESM.PDF

Additional file 3: Alternative recontruction of SWS1 opsin evolution, 2. Same tree as in Figure 2, but with all 'basal' nodes with posterior probability < 0.95 collapsed. VS/UVS optimisation represented by yellow for VS, blue for UVS, and barred for ambiguous. (PDF 359 KB)

12862_2011_1914_MOESM4_ESM.PDF

Additional file 4: Sequences used for phylogenetic reconstruction. GenBank numbers for sequences used for phylogenetic reconstruction. (PDF 64 KB)

12862_2011_1914_MOESM5_ESM.PDF

Additional file 5: Sequence alignment. Alignment of sequences used for phylogenetic reconstruction. Details in Additional file 4. (PDF 447 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ödeen, A., Håstad, O. & Alström, P. Evolution of ultraviolet vision in the largest avian radiation - the passerines. BMC Evol Biol 11, 313 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-11-313

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-11-313