Abstract

Background

Chronic bronchitis (CB) has been related to poor outcomes in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). From a clinical standpoint, we have shown that subjects with CB in a group with moderate to severe airflow obstruction were younger, more likely to be current smokers, male, Caucasian, had worse health related quality of life, more dyspnea, and increased exacerbation history compared to those without CB. We sought to further refine our clinical characterization of chronic bronchitics in a larger cohort and analyze the CT correlates of CB in COPD subjects. We hypothesized that COPD patients with CB would have thicker airways and a greater history of smoking, acute bronchitis, allergic rhinitis, and occupational exposures compared to those without CB.

Methods

We divided 2703 GOLD 1–4 subjects in the Genetic Epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene®) Study into two groups based on symptoms: chronic bronchitis (CB+, n = 663, 24.5%) and no chronic bronchitis (CB-, n = 2040, 75.5%). Subjects underwent extensive clinical characterization, and quantitative CT analysis to calculate mean wall area percent (WA%) of 6 segmental airways was performed using VIDA PW2 (http://www.vidadiagnostics.com). Square roots of the wall areas of bronchi with internal perimeters 10 mm and 15 mm (Pi10 and Pi15, respectively), % emphysema, %gas trapping, were calculated using 3D Slicer (http://www.slicer.org).

Results

There were no differences in % emphysema (11.4 ± 12.0 vs. 12.0 ± 12.6%, p = 0.347) or % gas trapping (35.3 ± 21.2 vs. 36.3 ± 20.6%, p = 0.272) between groups. Mean segmental WA% (63.0 ± 3.2 vs. 62.0 ± 3.1%, p < 0.0001), Pi10 (3.72 ± 0.15 vs. 3.69 ± 0.14 mm, p < 0.0001), and Pi15 (5.24 ± 0.22 vs. 5.17 ± 0.20, p < 0.0001) were greater in the CB + group. Greater percentages of gastroesophageal reflux, allergic rhinitis, histories of asthma and acute bronchitis, exposures to dusts and occupational exposures, and current smokers were seen in the CB + group. In multivariate binomial logistic regression, male gender, Caucasian race, a lower FEV1%, allergic rhinitis, history of acute bronchitis, current smoking, and increased airway wall thickness increased odds for having CB.

Conclusions

Histories of asthma, allergic rhinitis, acute bronchitis, current smoking, a lower FEV1%, Caucasian race, male gender, and increased airway wall thickness are associated with CB. These data provide clinical and radiologic correlations to the clinical phenotype of CB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

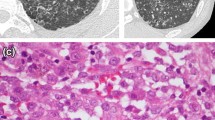

Chronic bronchitis (CB) affects 18-45% of COPD subjects and has been linked to multiple clinical sequelae including an increased exacerbation rate, accelerated decline in lung function, worse health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and possibly increased mortality [1–3]. The pathologic correlate to CB is goblet cell hyperplasia, which is well described in both the large and small airways in COPD subjects [4, 5]. Small airway mucus burden has been linked to mortality and changes in lung function after lung volume reduction surgery [6, 7]. A large lung pathology study also found that the number of small airways occluded by mucus plugs increased as COPD disease severity worsened [8].

Despite the clinical importance of CB on outcomes, our understanding of its pathophysiology is surprisingly poor. It is unclear why some individuals develop chronic bronchitis whereas others do not, despite similar environmental exposures. A thirty year longitudinal study found that 42% of continued smokers, 26% of ex-smokers, and 22% of never smokers developed CB [9]. To complicate matters, the correlation between symptoms and goblet cell hyperplasia is poor, and the most well described pathologic index of CB is weak at best [10]. An analysis of the National Emphysema Treatment Trial found no relationship with the severity of cough and sputum with small airway occlusion by mucus [11]. Thus, a better understanding of chronic bronchitis from a pathologic standpoint is needed.

An emerging surrogate for pathologic study is CT quantitative analysis of airway dimensions and emphysema. From a clinical standpoint, we have shown that chronic bronchitics in a group of 1,061 subjects from the COPDGene study with moderate to severe airflow obstruction were younger, more likely to be current smokers, male, Caucasian, had worse health related quality of life, more dyspnea, and increased exacerbation history compared to those without CB [2]. We sought to further refine our clinical characterization of chronic bronchitics in a larger cohort, analyze the CT correlates of CB in COPD subjects, and develop a prediction model for CB with these characteristics. We hypothesized that subjects with CB would have thicker airway walls, less emphysema, a greater percentage of current smoking, a greater overall history of smoking, a greater exposure to environmental fumes and dusts, and more allergic upper airway symptoms.

Methods

Patient selection

The Genetic Epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene®) Study is a multicenter observational study that recruited over 10,000 subjects to analyze genetic susceptibility for the development of COPD. This study underwent IRB approval at all centers. Inclusion and exclusion criteria and protocol were described previously [12]. Briefly, enrollees are African-American or non-Hispanic Caucasian between the ages of 45 and 80 with at least a 10 pack-year smoking history. Exclusion criteria include pregnancy, history of other lung disease except asthma, prior lobectomy or lung volume reduction, active cancer undergoing treatment, or known or suspected lung cancer. We used the March 2013 dataset with 10,192 subjects and included those with GOLD 1 through 4 COPD that had complete medical histories and quantitative CT assessments in our analysis. Subjects from our prior analysis [2] were included in this study.

Subjects were asked if they had cough; if they responded yes, they were asked if they coughed on most days for 3 consecutive months or more each year and for how many years. Similar questions were asked regarding phlegm production. Subjects were placed in 1) the chronic bronchitis group (CB+), if they had chronic cough and phlegm production for 3 months or more each year for at least two consecutive years; or 2) the no chronic bronchitis group (CB-), if these criteria were not satisfied. Figure 1 demonstrates the patient selection process.

Clinical characterization

Upper and lower respiratory tract symptoms were collected using a modified form of the American Thoracic Society Division of Lung Disease (ATS-DLD) Respiratory Epidemiology questionnaire. Medical comorbidities and occupational exposures were assessed based on subject self-report. Of particular interest were histories of asthma, episodes of acute bronchitis, allergic ocular and nasal symptoms, exposures to gases and fumes (defined as occupational exposures), exposures to dusts, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. The definition of acute bronchitis was determined by the answer to the question “Have you ever had an attack of bronchitis?” Subjects were asked specifically if they had these conditions and were instructed to answer yes or no. Subjects that answered “don’t know” to these questions were excluded from the analysis. Subjects were also asked if they experienced COPD exacerbations in the past year and to quantify the number of episodes, and if they have been to the emergency room or hospitalized for an exacerbation in the past year (defined as severe exacerbations). An exacerbation was defined as a flare-up of chest trouble requiring treatment with antibiotics and/or steroids. These answers were used to determine exacerbation history and history of severe exacerbations, respectively. Each subject underwent pre- and post-bronchodilator spirometry using an EasyOne™ spirometer (Zurich, Switzerland). Predicted values were obtained using NHANES III data. Six minute walk distance was measured in standard fashion [13].

Computed tomography

Volumetric chest CT acquisitions were obtained at full inspiration (200 mAs), and at the end of normal expiration (50 mAs) [12]. Thin-slice collimation with slice thickness and intervals of < lmm was used to enhance spatial resolution. Quantitative image analysis to calculate percent emphysema and percent gas-trapping was performed using 3D SLICER (http://www.slicer.org/). Percent emphysema was defined as the total percentage of both lungs with attenuation values less than −950 Hounsfield units on inspiratory images, and percent gas trapping was defined as the total percentage of both lungs with attenuation values less than −856 Hounsfield units on expiratory images. Airway disease was quantified as wall area percent (WA%: (wall area/total bronchial area)x100) using VIDA (http://www.vidadiagnostics.com) [14]. The mean WA% were calculated as the average of the values for six segmental bronchi in each subject. Using 3D SLICER, airway wall thickness was also expressed as the square root of the wall area of a hypothetical 10 mm and 15 mm internal perimeter airway (Pi10 and Pi15, respectively) as previously described [15].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata 13. Values are expressed as mean ± SD unless otherwise stated. CB + was the outcome of interest. The covariates analyzed in the model included gender, race, current smoking, smoking history, gastroesophageal reflux, COPD severity based on FEV1 and FVC, allergic eye and nasal symptoms, occupational exposures, exposure to dusts, history of asthma, history of acute bronchitis, and quantitative CT abnormalities (Pi10, Pi15, WA% seg). To reduce multicollinearity, principal axis factoring was used to estimate a wall thickness composite. Multivariable logistic regression using a trimmed covariate set selected via backward elimination with robust standard errors adjusting for within-clinic clustering was used to predict CB with all covariates associated with CB at p < .1 in at least one model retained. Interactions between predictors of interest and sex and race were considered in sensitivity analyses. All relevant assumptions were evaluated in the usual fashion (e.g., linearity of association, link tests, hat tests).

Results

The patient characteristics and univariate analysis of the groups are summarized in Table 1. There were a total of 4484 GOLD 1–4 subjects; of those with complete medical history and quantitative CT analysis, there were 2703 subjects, 2040 subjects in the CB- group and 663 in the CB + group (24.5% of total). The CB + group was younger, had a greater smoking history, and was more likely to be current smokers, Caucasian, and male. The CB + group had a lower forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC) and FEV1/FVC ratio. 6-minute walk distance was lower and MMRC dyspnea and BODE scores were higher in the CB + group as well. More subjects in the CB + group described gastroesophageal reflux (relative risk [RR] 1.2), allergic nasal and ocular symptoms (RRs 1.5 and 1.3, respectively), a history of asthma and acute bronchitis (RRs 1.4 and 1.3, respectively), and were more likely to be exposed to dusts and occupational exposures (RRs 1.4 and 1.3, respectively). Total exacerbation rate in the year prior to enrollment and history of severe exacerbations were higher in the CB + group as well. In a multivariable linear regression with FEV1, FVC, race, gender, mMRC dyspnea score, BMI, and CB as predictors of interest, CB was a significant predictor exacerbation frequency (β coefficient 0.295, p < 0.0001). The CB + group had a greater mean segmental wall area percent, Pi10, and Pi15. There were no differences in quantitative measures of percent emphysema or percent gas trapping between groups.

To assess for the possible confounding effects of active smoking, we performed a separate univariate analysis of active smokers versus those that did not currently smoke on the same variables. Active smokers walked a greater distance in 6 minutes (1288.58 ± 390.69 vs. 1189.95 ± 415.72 feet, p < 0.0001), were less dyspneic (MMRC scores 1.69 ± 1.48 vs. 2.07 ± 1.43, p < 0.0001), had lower SGRQ scores (36.07 ± 23.79 vs. 37.50 ± 22.22, p = 0.038), had better lung function (FEV1 63.5 ± 21.3 vs. 52.7 ± 22.8%, FVC 85.9 ± 19.9 vs. 78.8 ± 20.2%. p < 0.0001 for both), and had less emphysema and gas trapping (6.79 ± 8.83 vs. 15.25 ± 13.07% and 28.03 ± 18.88 vs. 41.58 ± 20.35%, respectively, p < 0.0001 for both). Fewer active smokers described allergic ocular or nasal symptoms, gastroesophageal reflux, or severe exacerbations. Airway wall thickness, however, was greater in active smokers, as measured by Pi10, Pi15, and WA% segmental.

Principal axis factoring

Principal axis factoring was used to reduce collinearity in wall area thickness measures. Two factors accounted for essentially 100% of the shared variance among wall area thickness measures, and each item loaded highly on only one factor. The rotated pattern matrix is shown in Table 2. Quartimax rotated factor scores were constructed using the regression method and agreed well (r > .99) with principal components results.

Table 3 summarizes the multivariate binomial logistic regression of the predictors of interest with chronic bronchitis as the outcome. In this multivariate analysis, there was no independent association between smoking history or occupational exposures and chronic bronchitis. Female gender and African American race were associated with lower odds ratios of CB (OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.59-0.79, and OR 0.57, 95% CI 0.43-0.76, respectively). Lower FEV1 and higher FVC were associated with a greater risk of CB (ORs 0.84, 95% CI 0.78-0.90 and 1.10, 95% CI 1.00-1.21, respectively, per 10% increase). The ORs for allergic ocular symptoms, allergic nasal symptoms, history of asthma, history of acute bronchitis, gastroesophageal reflux, and current smoking were 1.17, 2.11, 1.38, 1.65, 1.16, and 3.53, respectively (see Table 3 for 95% CIs). A composite value of the three CT airway variables (called wall thickness) conferred an OR of 1.19 (95% CI 1.02-1.37) for chronic bronchitis. Figure 2 shows the odds ratios for the predictors of interest.

As an additional set of sensitivity analyses, we considered potential interactions between each predictor of interest with sex and race for each predictor of interest separately and when entered as a group. None of the interaction terms remained significant after adjustment for multiple hypothesis tests. Figure 3 shows the receiver operator curve for all of the aforementioned predictors of interest in the model for chronic bronchitis as the outcome. The area under the curve is 0.75.

Discussion

We showed in a large cohort of 2,703 COPD subjects that chronic bronchitics were younger, had a reduced 6-minute walk distance, had a greater exacerbation frequency, were more likely to have gastroesophageal reflux, allergic ocular and nasal symptoms, histories of asthma and bronchitis, and were more likely to be current smokers, Caucasian, and male compared to those without CB, thereby validating our prior clinical findings in a smaller cohort that was less well characterized from a radiographic standpoint [2]. These findings were independent of the presence of active smoking. We also showed that the CB + group had a greater segmental wall area percent, Pi10, and Pi15 despite similar degrees of emphysema and gas trapping. Finally, we showed that the variables independently associated with CB were lung function, allergic rhinitis symptoms, history of acute bronchitis and asthma, airway wall thickness, exposure to dusts, gender, race, and current smoking in multivariate analysis. Using our prediction model, one can help identify those with the clinical phenotype of CB that is at higher risk for poor outcomes. To our knowledge, this is the first analysis that combines quantitative CT and clinical variables as predictors of CB in a large cohort of COPD subjects.

CB affects approximately 10 million individuals in the United States, and the majority are between 44 and 65 years of age [16]. CB has been associated with numerous adverse clinical outcomes. Exacerbation frequency has been shown to be greater in patients with COPD and CB in several studies [3, 17]. Seemungal et al. found that CB significantly increased the odds of having frequent exacerbations in a group of 70 patients [17]. A cross-sectional analysis of 433 patients also similarly found an increased risk of exacerbation among individuals with CB [3].

CB may increase all-cause mortality as well, independent of the level of airflow obstruction. Some but not all studies have shown CB to be an independent risk factor for death. In a study by Pelkonen et al., the multivariable hazard ratios for all-cause mortality in those with persistent CB was 1.64 (95% CI, 1.23–2.19) after adjustment for lung function [9]. In a post hoc analysis of the National Emphysema Treatment Trial, severe CB, defined as chronic cough, phlegm, and chest trouble, was associated with a higher mortality and hospitalization rate in those treated with medical therapy alone [18]. CB has also been shown to hasten the rate of lung function decline and reduce health related quality of life [2, 19, 20].

Radiographic characterization of COPD has been performed extensively in the past, [17, 18, 21] but few studies have related CT parameters to the clinical phenotype of CB. A small study of 42 COPD subjects showed that airway wall thickness was greater in those with CB compared to those without [22]. We have shown that percent emphysema and percent gas trapping were no different between those with CB and those without in 1061 moderate to severe COPD subjects [2]. We validate these prior findings on our study but add quantitative airway measurements in several compartments. Our findings of increased mean segmental wall area percent, Pi10, and Pi15 (“medium sized airways”) in chronic bronchitics is consistent with the notion that the clinical phenomenon of chronic bronchitis arises from mucus hypersecretion from larger more proximal airways, as opposed to small airway disease which is often difficult to detect clinically [11, 23]. This is, however, hypothesis generating and would require further study for confirmation. Although the differences in WA% were small, the composite variable of wall thickness was significantly associated with CB.

One of the strongest predictors of CB in this cohort was current smoking. Smoking causes airway inflammation and oxidative stress which induces mucin gene expression [1]. Active smokers have been shown in other studies to be at greater risk of CB. In a 30-year longitudinal study of 1,711 Finnish men, the cumulative incidence of CB was 42% in continuous smokers, 26% in ex-smokers, and 22% in never smokers [9]. A recent metaanalysis found that among 101 studies, ever smoking and current smoking were associated with relative risks of 2.69 and 3.41, respectively, for CB [24]. We showed that current smoking was associated with an odds ratio of 3.53 for CB.

Although the primary risk factor for CB is smoking, it should be noted that CB has been described in up to 22% of never smokers, [9] suggesting that other risk factors may exist. Other potential risk factors include inhalational exposures to biomass fuels, dusts, and chemical fumes [25, 26]. A survey of South African adults found occupational exposure to be a risk factor for CB in men (OR 2.6; 95% CI 1.7–4.0) and domestic fuel exposure to be a risk factor for CB in women (OR, 1.9; 95% CI 1.4–2.6) [27]. In a recent analysis of 5,858 smokers or ex-smokers without COPD, patients with CB were more likely to have been exposed to fumes at work (76.4 vs. 60.9%, P < 0.001) or to have worked more than 1 year at a dusty job (76 vs. 57%, P < 0.001) [28]. We found that subjects with CB had a 1.4-fold and 1.3-fold increased risk for exposure to dusts and occupational exposures, respectively. Although occupational exposures were not statistically significant in the multivariate predictive model, we present some evidence of their association in univariate analysis, providing more evidence of a causal association.

Another potential risk factor for CB is the presence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), possibly by pulmonary aspiration of refluxed gastric contents producing acid-induced injury and infection or neurally mediated reflex bronchoconstriction secondary to irritation of esophageal mucosa [29]. There is increasing evidence that not only is GERD a significant comorbidity but also that it is a risk factor for COPD related outcomes. For example, the Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) study identified GERD as a risk factor for COPD exacerbations in longitudinal follow-up [30]. In the Azithromycin for Prevention of Exacerbations of COPD (MACRO) trial, GERD was associated with an increased risk of COPD exacerbations [31]. In our study, we demonstrated that GERD was more common in those with CB and that GERD conferred a slightly increased odds ratio of having CB in multivariate analysis that almost reached statistical significance.

Other risk factors identified in our study include a history of acute bronchitis, and allergic nasal symptoms. Repeated bouts of acute bronchitis has been considered a risk factor for the development of CB, [32] possibly by the development of persistent inflammation and mucus hypersecretion after multiple episodes of infectious bronchitis. Mucus hypersecretion is a signature pathologic feature of asthma, and asthma’s association with allergic rhinitis is strong. The association between chronic bronchitis and allergic nasal symptoms suggests a link between upper and lower airway inflammation that has commonly been described in asthma. This raises the possibility of a common pathophysiology between CB and asthma, which deserves further attention.

The influence of gender on CB continues to be a matter of debate. Many studies have found that CB affects men more than women, [2, 33, 34] but in the 2009 National Center for Health Statistics report, 67.8% of patients with CB were women [35]. The reasons for the higher prevalence of CB in women compared with men is unclear, but may be due to hormonal influences, sex differences in symptom reporting, and sex diagnostic bias. Our study showed that men were more likely to be affected by CB and that gender was an independent predictor of CB in multivariate analysis.

Despite the clinical and CT findings in this robust cohort of unselected COPD subjects, there are several limitations that are worthy of mention. First, the assessment of medical history and exposures was by self-report, potentially leading to recall bias. The outcome of interest itself is somewhat subjective as well (chronic cough and phlegm). Although the identified clinical and computed tomographic factors were used in a prediction model, one could argue that some of predictors of interest are caused by chronic bronchitis, not the result of it (eg, airway wall thickness). In addition, it is unclear why the FVC is lower in chronic bronchitics in univariate analysis but higher in multivariate analysis; this phenomenon is most likely due to the confounding factors of differences in FEV1, race, and gender. However, the predictors of interest were chosen because of the more likely causal relationship of CB. Nonetheless, our analysis offers a comprehensive characterization of chronic bronchitis in COPD as well as a prediction model for CB using several clinical and computed tomographic parameters.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we show that allergic rhinitis, acute bronchitis, asthma, male gender, Caucasian race, lung function, current smoking, and airway wall thickness are associated with clinical phenotype of CB. We also show in a large cohort that CB is associated with greater exacerbation frequency, worse health related quality of life, and a lower 6-minute walk distance. Identification of these clinical and CT parameters can help predict the clinical phenotype of CB and can help stratify patients into a group at higher risk for poor outcomes. This group should receive treatment for their comorbidities and receive targeted therapy towards smoking cessation.

Abbreviations

- CB:

-

Chronic bronchitis

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- FEV1:

-

Forced expiratory volume in one second

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- GERD:

-

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- HRQoL:

-

Health related quality of life

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- Pi10:

-

Square root of wall area of 10mm airway

- Pi15:

-

Square root of wall area of 15mm airway

- RR:

-

Relative risk

- WA%:

-

Wall area percent.

References

Kim V, Criner GJ: Chronic bronchitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013, 187: 228-237. 10.1164/rccm.201210-1843CI.

Kim V, Han MK, Vance GB, Make BJ, Newell JD, Hokanson JE, Hersh CP, Stinson D, Silverman EK, Criner GJ: The chronic bronchitic phenotype of COPD: an analysis of the COPDGene study. Chest. 2011, 140: 626-633. 10.1378/chest.10-2948.

Burgel PR, Nesme-Meyer P, Chanez P, Caillaud D, Carre P, Perez T, Roche N, Initiatives Bronchopneumopathie Chronique Obstructive Scientific Committee: Cough and sputum production are associated with frequent exacerbations and hospitalizations in COPD subjects. Chest. 2009, 135: 975-982. 10.1378/chest.08-2062.

Innes AL, Woodruff PG, Ferrando RE, Donnelly S, Dolganov GM, Lazarus SC, Fahy JV: Epithelial mucin stores are increased in the large airways of smokers with airflow obstruction. Chest. 2006, 130: 1102-1108. 10.1378/chest.130.4.1102.

Saetta M, Turato G, Baraldo S, Zanin A, Braccioni F, Mapp CE, Maestrelli P, Cavallesco G, Papi A, Fabbri LM: Goblet cell hyperplasia and epithelial inflammation in peripheral airways of smokers with both symptoms of chronic bronchitis and chronic airflow limitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000, 161: 1016-1021. 10.1164/ajrccm.161.3.9907080.

Hogg JC, Chu FS, Tan WC, Sin DD, Patel SA, Pare PD, Martinez FJ, Rogers RM, Make BJ, Criner GJ, Cherniack RM, Sharafkhaneh A, Luketich JD, Coxson HO, Elliott WM, Sciurba FC: Survival after lung volume reduction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: insights from small airway pathology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007, 176: 454-459. 10.1164/rccm.200612-1772OC.

Kim V, Criner GJ, Abdallah HY, Gaughan JP, Furukawa S, Solomides CC: Small airway morphometry and improvement in pulmonary function after lung volume reduction surgery. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005, 171: 40-47. 10.1164/rccm.200405-659OC.

Hogg JC, Chu F, Utokaparch S, Woods R, Elliott WM, Buzatu L, Cherniack RM, Rogers RM, Sciurba FC, Coxson HO, Pare PD: The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2004, 350: 2645-2653. 10.1056/NEJMoa032158.

Pelkonen M, Notkola IL, Nissinen A, Tukiainen H, Koskela H: Thirty-year cumulative incidence of chronic bronchitis and COPD in relation to 30-year pulmonary function and 40-year mortality: a follow-up in middle-aged rural men. Chest. 2006, 130: 1129-1137. 10.1378/chest.130.4.1129.

Reid LM: Pathology of chronic bronchitis. Lancet. 1954, 266: 274-278.

Sciurba F, Martinez FJ, Rogers RM, Make B, Criner GJ, Cherniak RM, Patel SA, Chu F, Coxson HO, Sharafkhaneh A, Elliott WM, Luketich JD, Sin DD, Hogg JC: The effect of small airway pathology on survival following lung volume reduction surgery (LVRS): [abstract]. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006, 3: A712-

Regan EA, Hokanson JE, Murphy JR, Make B, Lynch DA, Beaty TH, Curran-Everett D, Silverman EK, Crapo JD: Genetic epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) study design. COPD. 2010, 7: 32-43. 10.3109/15412550903499522.

ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories: ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002, 166: 111-117.

Nakano Y, Muro S, Sakai H, Niimi A, Kalloger SE, Mishima M, Pare PD: Computed tomographic measurements of airway dimensions and emphysema in smokers: correlation with lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000, 162: 1102-1108. 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9907120.

Patel BD, Coxson HO, Pillai SG, Agusti AG, Calverley PM, Donner CF, Make BJ, Muller NL, Rennard SI, Vestbo J, Wouters EF, Hiorns MP, Nakano Y, Camp PG, Nasute Fauerbach PV, Screaton NJ, Campbell EJ, Anderson WH, Pare PD, Levy RD, Lake SL, Silverman EK, Lomas DA: Airway wall thickening and emphysema show independent familial aggregation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008, 178: 500-505. 10.1164/rccm.200801-059OC.

American Lung Association: Trends in COPD (Chronic Bronchitis and Emphysema): Morbidity and Mortality. 2011, Available at http://www.lung.org/finding-cures/our-research/trend-reports/copd-trend-report.pdf

Seemungal TA, Donaldson GC, Bhowmik A, Jeffries DJ, Wedzicha JA: Time course and recovery of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000, 161: 1608-1613. 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9908022.

Nakano Y, Muller NL, King GG, Niimi A, Kalloger SE, Mishima M, Pare PD: Quantitative assessment of airway remodeling using high-resolution CT. Chest. 2002, 122: 271S-275S.

Vestbo J, Prescott E, Lange P: Association of chronic mucus hypersecretion with FEV1 decline and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease morbidity. Copenhagen City Heart Study Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996, 153: 1530-1535. 10.1164/ajrccm.153.5.8630597.

Sherman CB, Xu X, Speizer FE, Ferris BG, Weiss ST, Dockery DW: Longitudinal lung function decline in subjects with respiratory symptoms. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992, 146: 855-859. 10.1164/ajrccm/146.4.855.

Achenbach T, Weinheimer O, Biedermann A, Schmitt S, Freudenstein D, Goutham E, Kunz RP, Buhl R, Dueber C, Heussel CP: MDCT assessment of airway wall thickness in COPD patients using a new method: correlations with pulmonary function tests. Eur Radiol. 2008, 18: 2731-2738. 10.1007/s00330-008-1089-4.

Orlandi I, Moroni C, Camiciottoli G, Bartolucci M, Pistolesi M, Villari N, Mascalchi M: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: thin-section CT measurement of airway wall thickness and lung attenuation. Radiology. 2005, 234: 604-610. 10.1148/radiol.2342040013.

Gelb AF, Zamel N, Hogg JC, Muller NL, Schein MJ: Pseudophysiologic emphysema resulting from severe small-airways disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998, 158: 815-819. 10.1164/ajrccm.158.3.9801045.

Forey BA, Thornton AJ, Lee PN: Systematic review with meta-analysis of the epidemiological evidence relating smoking to COPD, chronic bronchitis and emphysema. BMC Pulm Med. 2011, 11: 36-10.1186/1471-2466-11-36. 2466-11-36

Trupin L, Earnest G, San Pedro M, Balmes JR, Eisner MD, Yelin E, Katz PP, Blanc PD: The occupational burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2003, 22: 462-469. 10.1183/09031936.03.00094203.

Matheson MC, Benke G, Raven J, Sim MR, Kromhout H, Vermeulen R, Johns DP, Walters EH, Abramson MJ: Biological dust exposure in the workplace is a risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2005, 60: 645-651. 10.1136/thx.2004.035170.

Ehrlich RI, White N, Norman R, Laubscher R, Steyn K, Lombard C, Bradshaw D: Predictors of chronic bronchitis in South African adults. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004, 8: 369-376.

Martinez CH, Kim V, Chen Y, Kazerooni EA, Murray S, Criner GJ, Curtis JL, Regan EA, Wan E, Hersh CP, Silverman EK, Crapo JD, Martinez FJ, Han MK, The Copdgene Investigators: The clinical impact of non-obstructive chronic bronchitis in current and former smokers. Respir Med. 2013, in press

Barish CF, Wu WC, Castell DO: Respiratory complications of gastroesophageal reflux. Arch Intern Med. 1985, 145: 1882-1888. 10.1001/archinte.1985.00360100152025.

Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, Locantore N, Mullerova H, Tal-Singer R, Miller B, Lomas DA, Agusti A, Macnee W, Calverley P, Rennard S, Wouters EF, Wedzicha JA, Evaluation Of Copd Longitudinally To Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (Eclipse) Investigators: Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2010, 363: 1128-1138. 10.1056/NEJMoa0909883.

Ramos F, Krahnke JS, Harnden SM, Connett J, Albert RK, Criner GJ: Acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in patients with and without history of gastroesophageal reflux disease: [abstract]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013, 187: A5704-

Desai P, Kim V: Management of chronic bronchitis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. US Resp Rev. 2011, 7: 102-106.

de Oca MM, Halbert RJ, Lopez MV, Perez-Padilla R, Talamo C, Moreno D, Muino A, Jardim JR, Valdivia G, Pertuze J, Meneze AM: The chronic bronchitis phenotype in subjects with and without COPD: the PLATINO study. Eur Respir J. 2012, 40: 28-36. 10.1183/09031936.00141611.

Speizer FE, Fay ME, Dockery DW, Ferris BG: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease mortality in six U.S. cities. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989, 140: S49-55. 10.1164/ajrccm/140.3_Pt_2.S49.

Kim V, Sternberg AL, Washko GR, Make BJ, Han MK, Martinez FJ, Criner GJ: Severe chronic bronchitis in advanced emphysema increases mortality and hospitalizations. J COPD. 2013, 10: 667-678. 10.3109/15412555.2013.827166.

Acknowlegements

We acknowledge and thank the COPDGene Core Teams:

Administrative Core: James D. Crapo, MD (PI); Edwin K. Silverman, MD, PhD (PI); Barry J. Make, MD; Elizabeth A. Regan, MD, PhD; Stephanie Bratschie, MPH; Rochelle Lantz; Sandra Melanson, MSW, LCSW; Lori Stepp.

Executive Committee: Terri Beaty, PhD; Russell P. Bowler, MD, PhD; James D. Crapo, MD; Jeffrey L. Curtis, MD; Douglas Everett, PhD; MeiLan K. Han, MD, MS; John E. Hokanson, MPH, PhD; David Lynch, MB; Barry J. Make, MD; Elizabeth A. Regan, MD, PhD; Edwin K. Silverman, MD, PhD; E. Rand Sutherland, MD.

External Advisory Committee: Eugene R. Bleecker, MD; Harvey O. Coxson, PhD; Ronald G. Crystal, MD; James C. Hogg, MD; Michael A. Province, PhD; Stephen I. Rennard, MD; Duncan C. Thomas, PhD.

NHLBI: Thomas Croxton, MD, PhD; Weiniu Gan, PhD; Lisa Postow, PhD.

COPD Foundation: John W. Walsh; Randel Plant; Delia Prieto.

Data Coordinating Center: Douglas Everett, PhD; Andre Williams, PhD; Ruthie Knowles; Carla Wilson, MS.

Epidemiology Core: John Hokanson, MPH, PhD; Jennifer Black-Shinn, MPH; Gregory Kinney, MPH.

Genetic Analysis Core: Terri Beaty, PhD; Peter J. Castaldi, MD, MSc; Michael Cho, MD; Dawn L. DeMeo, MD, MPH; Marilyn G. Foreman, MD, MS; Nadia N. Hansel, MD, MPH; Megan E. Hardin, MD; Craig Hersh, MD, MPH; Jacqueline Hetmanski, MS; John E. Hokanson, MPH, PhD; Nan Laird, PhD; Christoph Lange, PhD; Sharon M. Lutz, MPH, PhD; Manuel Mattheisen, MD; Merry-Lynn McDonald, MSc, PhD; Margaret M. Parker, MHS; Elizabeth A. Regan, MD, PhD; Stephanie Santorico, PhD; Edwin K. Silverman, MD, PhD; Emily S. Wan, MD; Jin Zhou, PhD.

Genotyping Cores: Genome-Wide Core: Terri Beaty, PhD; Candidate Genotyping Core: Craig P. Hersh, MD, MPH; Edwin K. Silverman, MD, PhD.

Imaging Core: David Lynch, MB; Mustafa Al Qaisi, MD; Jaleh Akhavan; Christian W. Cox, MD; Harvey O. Coxson, PhD; Deanna Cusick; Jennifer G. Dy, PhD; Shoshana Ginsburg, MS; Eric A. Hoffman, PhD; Philip F. Judy, PhD; Alex Kluiber; Alexander McKenzie; John D. Newell, Jr., MD; John J. Reilly, Jr., MD; James Ross, MSc; Raul San Jose Estepar, PhD; Joyce D. Schroeder, MD; Jered Sieren; Arkadiusz Sitek, PhD; Douglas Stinson; Edwin van Beek, MD, PhD, MEd; George R. Washko, MD; Jordan Zach.

PFT QA Core: Robert Jensen, PhD; E. Rand Sutherland, MD.

Biological Repository, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD: Homayoon Farzadegan, PhD: Samantha Bragan; Stacey Cayetano.

We further wish to acknowledge the COPDGene Investigators from the participating Clinical Centers:

Ann Arbor VA: Jeffrey Curtis, MD, Ella Kazerooni, MD.

Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX: Nicola Hanania, MD, MS, Philip Alapat, MD, Venkata Bandi, MD, Kalpalatha Guntupalli, MD, Elizabeth Guy, MD, Antara Mallampalli, MD, Charles Trinh, MD, Mustafa Atik, MD, Hasan Al-Azzawi, MD, Marc Willis, DO, Susan Pinero, MD, Linda Fahr, MD, Arun Nachiappan, MD, Collin Bray, MD, L. Alexander Frigini, MD, Carlos Farinas, MD, David Katz, MD, Jose Freytes, MD, Anne Marie Marciel, MD.

Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA: Dawn DeMeo, MD, MPH, Craig Hersh, MD, MPH, George Washko, MD, Francine Jacobson, MD, MPH, Hiroto Hatabu, MD, PhD, Peter Clarke, MD, Ritu Gill, MD, Andetta Hunsaker, MD, Beatrice Trotman-Dickenson, MBBS, Rachna Madan, MD.

Columbia University, New York, NY: R. Graham Barr, MD, Dr PH, Byron Thomashow, MD, John Austin, MD, Belinda D’Souza, MD.

Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC: Neil MacIntyre, Jr., MD, Lacey Washington, MD, H Page McAdams, MD.

Fallon Clinic, Worcester, MA: Richard Rosiello, MD, Timothy Bresnahan, MD, Joseph Bradley, MD, Sharon Kuong, MD, Steven Meller, MD, Suzanne Roland, MD.

Health Partners Research Foundation, Minneapolis, MN: Charlene McEvoy, MD, MPH, Joseph Tashjian, MD.

Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD: Robert Wise, MD, Nadia Hansel, MD, MPH, Robert Brown, MD, Gregory Diette, MD, Karen Horton, MD.

Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA: Richard Casaburi, MD, Janos Porszasz, MD, PhD, Hans Fischer, MD, PhD, Matt Budoff, MD, Mehdi Rambod, MD.

Michael E. DeBakey VAMC, Houston, TX: Amir Sharafkhaneh, MD, Charles Trinh, MD, Hirani Kamal, MD, Roham Darvishi, MD, Marc Willis, DO, Susan Pinero, MD, Linda Fahr, MD, Arun Nachiappan, MD, Collin Bray, MD, L. Alexander Frigini, MD, Carlos Farinas, MD, David Katz, MD, Jose Freytes, MD, Anne Marie Marciel, MD.

Minneapolis VA: Dennis Niewoehner, MD, Quentin Anderson, MD, Kathryn Rice, MD, Audrey Caine, MD.

Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA: Marilyn Foreman, MD, MS, Gloria Westney, MD, MS, Eugene Berkowitz, MD, PhD.

National Jewish Health, Denver, CO: Russell Bowler, MD, PhD, David Lynch, MB, Joyce Schroeder, MD, Valerie Hale, MD, John Armstrong, II, MD, Debra Dyer, MD, Jonathan Chung, MD, Christian Cox, MD.

Temple University, Philadelphia, PA: Gerard Criner, MD, Victor Kim, MD, Nathaniel Marchetti, DO, Aditi Satti, MD, A. James Mamary, MD, Robert Steiner, MD, Chandra Dass, MD, Libby Cone, MD.

University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL: William Bailey, MD, Mark Dransfield, MD, Michael Wells, MD, Surya Bhatt, MD, Hrudaya Nath, MD, Satinder Singh, MD.

University of California, San Diego, CA: Joe Ramsdell, MD, Paul Friedman, MD.

University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA: Alejandro Cornellas, MD, John Newell, Jr., MD, Edwin JR van Beek, MD, PhD.

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI: Fernando Martinez, MD, MeiLan Han, MD, Ella Kazerooni, MD.

University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN: Christine Wendt, MD, Tadashi Allen, MD.

University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA: Frank Sciurba, MD, Joel Weissfeld, MD, MPH, Carl Fuhrman, MD, Jessica Bon, MD, Danielle Hooper, MD.

University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX: Antonio Anzueto, MD, Sandra Adams, MD, Carlos Orozco, MD, Mario Ruiz, MD, Amy Mumbower, MD, Ariel Kruger, MD, Carlos Restrepo, MD, Michael Lane, MD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

This study was supported by the NHLBI R01 HL089856 and R01 HL08989.

VK is supported by NHLBI K23HL094696-03.

VK has participated in clinical trials sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, and Roche pharmaceuticals. AD, JC, and CHM report no conflicts. APC has been a consultant for VIDA diagnostics. Also, APC has participated in clinical trials sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, and Astra-Zeneca, and Forest. MKH has participated in advisory boards for Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Genentech, Novartis, and Medimmune; participated on speaker’s bureaus for Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Forest, Grifols therapeutics, and the National Association for Continuing Education, and WebMD; has consulted for Novartis, Ikaria and United Biosource Corporation; and has received royalties from UpToDate and ePocrates. GW has received grants from the NHLBI to perform quantitative image analysis and have been a paid consultant for MedImmune and Spiration, and his spouse is an employee of Merck Research Laboratories. Over the last three years, BJM has participated in advisory boards, speaker bureaus, consultations and multi-center clinical trials with funding from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, Abbott, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Boerhinger-Ingelheim, Coviden, Dey, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, MedImmune, NABI, Novartis, Pfizer, Respironics, Sepracor, Sequal and Talecris. EKS received grant support from GlaxoSmithKline for studies of COPD genetics, and he received honoraria and consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Merck, and GlaxoSmithKline. DAL’s institution and laboratory receives research support from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, Siemens, Inc, Perceptive Imaging, Inc, and Centocor, Inc, Inc. Dr Lynch is a consultant to Perceptive Imaging, Inc, Boehringer Ingelheim, Inc, Genentech, Inc, Gilead, Inc, Veracyte, Inc and Intermune, Inc. GJC has served on Advisory Committees for Boehringer Ingelheim, CSA, Amirall and Holaira. All of these sums are less than $2,500. GJC has received research grants from: Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, MedImmune, Pearl, Actelion, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Forest, Aeris, Therapeutics, Pulmonx and PneumRx. All research grant monies are deposited and controlled by Temple University.

Authors’ contributions

All authors participated in the study design, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript. VK is the guarantor for the overall content.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, V., Davey, A., Comellas, A.P. et al. Clinical and computed tomographic predictors of chronic bronchitis in COPD: a cross sectional analysis of the COPDGene study. Respir Res 15, 52 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-15-52

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-15-52