Abstract

The recent worldwide spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (MRSP) in dogs is a reason for concern due to the typical multidrug resistance patterns displayed by some MRSP lineages such as sequence type (ST) 71. The objective of this study was to compare the in vitro adherence properties between MRSP and methicillin-susceptible (MSSP) strains. Four MRSP, including a human and a canine strain belonging to ST71 and two canine non-ST71 strains, and three genetically unrelated MSSP were tested on corneocytes collected from five dogs and six humans. All strains were fully characterized with respect to genetic background and cell wall-anchored protein (CWAP) gene content. Seventy-seven strain-corneocyte combinations were tested using both exponential- and stationary-phase cultures. Negative binomial regression analysis of counts of bacterial cells adhering to corneocytes revealed that adherence was significantly influenced by host and strain genotype regardless of bacterial growth phase. The two MRSP ST71 strains showed greater adherence than MRSP non-ST71 (p < 0.0001) and MSSP (p < 0.0001). This phenotypic trait was not associated to any specific CWAP gene. In general, S. pseudintermedius adherence to canine corneocytes was significantly higher compared to human corneocytes (p < 0.0001), but the MRSP ST71 strain of human origin adhered equally well to canine and human corneocytes, suggesting that MRSP ST71 may be able to adapt to human skin. The genetic basis of the enhanced in vitro adherence of ST71 needs to be elucidated as this phenotypic trait may be associated to the epidemiological success and zoonotic potential of this epidemic MRSP clone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Staphylococcus pseudintermedius is the most common bacterial pathogen associated with otitis and pyoderma in dogs, which are the natural hosts of this staphylococcal species. The reported carriage prevalences in healthy dogs range between 46 and 92% depending on the study population and methodology used for assessing carriage [1]. Methicillin-resistant S. pseudintermedius (MRSP) were first reported in the United States in 1999 [2] and in 2007 in Europe [3]. An increasing number of studies have documented the rapid spread of MRSP worldwide [4–8]. Some strains are resistant to all antibiotics available for treatment in small animal practice and two dominant clonal lineages have been recognized: ST71 in Europe and ST68 in North America [6]. It has been demonstrated that MRSP ST71 isolates are better biofilm producers compared to other MRSP clones [9]. Although the ability to form biofilm may play an important role in the pathophysiology of bacterial infections and be related to survival and persistence of S. pseudintermedius in the environment [9, 10], the reasons for the rapid emergence and success of this lineage remain unknown.

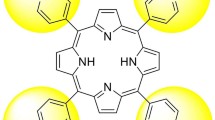

Recent studies have documented carriage of MRSP among veterinary staff and pet owners [11–14]. Sporadic cases of human infection have also been reported, including patients exposed to colonized household pets [15–17]. Staphylococcal adherence to corneocytes is the first important step to skin colonization. S. aureus adherence to skin and mucosae results from the interaction between host extracellular matrix proteins, such as fibrinogen, fibronectin and cytokeratin 10, and bacterial cell wall-associated proteins (CWAPs) termed microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules (MSCRAMMs) [18]. Eighteen CWAP genes have been described in S. pseudintermedius[19], and are hypothesized to play a role in pathogenesis [20, 21].

To shed light on the epidemiological success and zoonotic potential of MRSP, the in vitro adherence properties of four MRSP strains belonging to three unrelated sequence types (ST71, ST68 and ST258) were compared to those of three genetically unrelated methicillin-susceptible (MSSP) strains (ST25, ST257, ST259) using corneocytes obtained from five dogs and six humans. The CWAP gene profiles of all strains were determined to identify possible associations with adherence ability.

Materials and methods

Strains

The four MRSP and three MSSP strains used in this study were isolated from different body sites of healthy and diseased dogs and from the nostrils of healthy humans (Table 1). All strains were typed by the new seven genes multilocus sequence typing scheme (MLST) [22], spa typing [6], and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) [23]. The MRSP strains were selected to represent the two epidemic clones ST71 and ST68 [6], and ST258 (ST106 according to the old MLST scheme), which is an emerging clone in the Scandinavian countries [9, 24]. MRSP ST71 was represented by two strains of canine and human origin. ED99, a whole genome sequenced strain [25] and two randomly selected strains from a healthy dog [23] and a dog owner [26] were used as MSSP strains. For all strains, the presence of genes encoding 18 putative CWAPs from SpsA to SpsR was determined by PCR using strain ED99 as a positive control as described by Bannoehr et al. [19].

Collection of corneocytes

Corneocytes were collected from five dogs of different breeds (one Rottweiler, one Parson Jack Russel Terrier, one Springel Spaniel and two Shetland Sheepdog; age range: 6–10 years) and from six humans (age range: 30–35 years). The dogs were healthy with no symptoms of skin or ear infection, and had no history of systemic or local antimicrobial therapy in the last six months before sampling. None of the human donors had a history of skin disorder or reported to have frequent contacts with dogs. Written informed consent was obtained for each canine and human donor prior to sampling. Corneocytes were collected by applying adhesive discs of 25-mm diameter (D-squame, CuDerm Corporation, Dallas, USA) on the canine skin of the inner concave side of the pinna and on the human inner forearm [27, 28]. Twenty-eight discs with confluent corneocytes layer were obtained from each donor at the same time to avoid sampling variability. Before collection, surface debris was removed by applying five successive adhesive tape strips (Sellotape® Original, Winsford, Cheshire, UK). After collection, the adhesive discs were examined by light microscopy to evaluate the confluency of the corneocytes layer, and then stored at 4 °C for a maximum of 10 months. At the time of collection, all donors were screened for S. pseudintermedius. Canine oral and perineal swabs and human nasal swabs were collected and processed as described before [12, 23].

In vitro corneocytes adherence assay

All experiments were carried out using bacterial cultures in mid-exponential and late stationary phase. Briefly, each strain was inoculated into 10 mL BHI and incubated at 37 °C for 14–16 h (late stationary phase culture). After the overnight incubation, 100 μL of bacterial culture was transferred into 30 mL BHI and incubated at 37 °C until optical density (OD)600= 0.750 ± 0.030 (mid-exponential phase culture). Thereafter, 8 mL were centrifuged at 1500 g for 5 min at 4 °C, and the resulting pellet was washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Dulbecco’s Phosphate-buffered saline no calcium no magnesium, GIBCO) by pipetting and centrifugation (800 g for 3 min). The final bacterial suspension was adjusted to an OD600= 0.15, which corresponds to ~ 7 × 107 CFU/mL in stationary phase and ~3 × 107 CFU/mL in exponential phase. Subsequently, 500 μL of OD-adjusted suspension was pipetted onto D-squame discs with adhered corneocytes to form a meniscus and incubated at 37 °C for 45 min in a moist chamber. After incubation, the discs were washed with PBS for three times (3 × 10 s) and air dried. Discs were stained for one minute with 500 μL of 0.5% crystal violet and washed with PBS to remove excess stain. The number of adherent bacteria was counted at × 1000 magnification using an Axioplan II epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and a Zeiss AxioCam digital camera. Ten microscopic field images with confluent corneocytes were randomly selected, except for dog D2 with strain 2M in stationary phase where it was possible to use only three fields due to poor confluent corneocyte layer. One slide for each combination of strain, growth phase (mid-exponential or stationary) and corneocytes donor (dog or human) was used. To assess the reproducibility of the results in our setting, a pilot experiment was performed where the combinations of each strain in stationary phase and human corneocytes were tested in duplicate. One corneocytes disc per individual was incubated with PBS only and used as a negative control.

Statistical analyses

The mean counts for all combinations of three strain genotypes (MRSP ST71, MRSP non-ST71 and MSSP), two growth phases (mid-exponential and stationary), two strain host origins (dog or human) and two corneocytes donor types (dog or human), were compared in a negative binomial regression model using the Genmod procedure in SAS v. 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). All ten replicates within each donor were treated as repeated samples within a donor in the model. This model was used to compare adherence of S. pseudintermedius to corneocytes among the different strain genotypes, the strain host origin, the corneocytes donor origin and the S. pseudintermedius colonization status of the donor at the time of the collection of corneocytes while stratifying in the exponential and the stationary phase. A p-value of < 0.05 was deemed significant.

Results

Four out of five canine corneocyte donors were positive for S. pseudintermedius, whereas all six human donors were negative. No statistically significant difference was found between colonization status at the time of the collection of corneocytes and adherence. Mean bacterial counts were affected by host (Figure 1) and strain genotype (Figure 2). Overall, S. pseudintermedius showed significantly greater adherence to canine corneocytes than to human corneocytes (p < 0.0001) (Figure 1). Preferential adherence to canine corneocytes was particularly evident for two MSSP isolated from dogs, ED99 and 2M (Figure 3). None of the strains showed a statistically significant preferential adherence to human corneocytes but the MRSP ST71 strain of human origin was the best adhering strain to both canine and human corneocytes (Figure 3), with double number of adhering bacteria to human corneocytes (mean count of all six human corneocytes = 150) compared to canine corneocytes (mean count of all five canine corneocytes = 72) in stationary phase (Figure 3B). In general, the mean adherent count of each strain was higher in mid-exponential phase than in stationary phase (Figure 3) and significant differences in adherence ability were observed between mean counts of MRSP and MSSP in stationary phase (p < 0.001) but not in the exponential phase (p = 0.05). Interestingly, MRSP ST71 showed greater adherence than MRSP non-ST71 and MSSP (p < 0.0001) regardless of growth phase (Figure 2). Strain host origin and the possible interactions among all investigated parameters were not significant. No bacteria were observed in the negative control corneocytes discs, confirming that corneocytes were not contaminated with strains from the donor after removal of surface debris prior to the corneocytes collection. No statistically significant differences were found between the mean bacterial counts of the two slides used to assess the reproducibility of the results in the pilot experiment.

Mean adhesion counts of the seven Staphylococcus pseudintermedius strains to human and canine corneocytes. (A) Exponential phase. (B) Stationary phase. Bars represent the mean counts of adherent Staphylococcus pseudintermedius per 10 microscopic field images and the error bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals. The two strains of human origin are marked by an asterisk.

All seven strains were positive for 13/18 CWAP genes (namely spsA-C, spsE, spsG, spsH, spsI-N, spsR). The remaining five genes; spsD, spsF, spsO and the S. aureus spa orthologues spsP and spsQ were present in different combinations (Table 1). Strain adherence was not associated to any specific CWAP gene combination. The SpsO sequence detected in 2M was 105 bp smaller compared to the expected size and showed 97% nucleotide identity with SpsO ED99.

Discussion

We evaluated the adherence properties of MRSP and MSSP, showing that MRSP ST71 adhered better to canine and human corneocytes than MRSP non-ST71 and MSSP. The enhanced adherence of ST71 compared to other genotypes may explain the epidemiological success of this clone, which was first detected in Europe in 2007 [3] and then rapidly spread within this continent as well as in countries outside Europe such as Brazil, USA and Canada [6, 29]. MRSP ST71 has recently been shown to have a greater ability to produce biofilm compared with other STs [9, 10]. Taken together, these data indicate that this clone has a particular ability to adhere to skin and form biofilm compared to other members of the species, even though the genetic factors associated with these phenotypic traits remain to be identified.

All seven strains were tested using both mid-exponential and stationary phase because it has previously been shown in S. aureus, that cell wall adhesins and secreted virulence factors are differentially expressed during the bacterial growth cycle [30, 31]. Adhesins are hypothesized to be predominantly expressed in exponential phase and at low cell densities, while toxins and other secreted virulence factors are expressed in post exponential phase and at high cell densities for host tissue invasion and dissemination [30, 31]. As expected, all S. pseudintermedius had greater mean adherence counts in the mid-exponential phase compared to the stationary phase following the time-dependent expression pattern regulated by agr system in other staphylococcal species [32]. Interestingly, when analyzing MRSP vs MSSP, statistical differences were observed only in stationary phase. This observation could be a result of the differences between groups in the protein expression patterns and persistence of surface adhesins. Such differences were recently reported for the S. aureus surface adhesion proteins SdrD and SdrE [32] which have a biphasic expression pattern, and for clumping factor B and fibronectin-binding proteins (FnBPs) [33], which can be present throughout the bacterial growth cycle.. Georghean et al. [33] showed that high-level expression of FnBPs throughout the bacterial growth cycle is requested to promote the accumulation phase of ica-indipendent biofilm formation in methicillin-resistant S. aureus[33] and this may be also the case in MRSP.

S. pseudintermedius have significantly greater adherence to canine corneocytes than to human corneocytes, as indicated by previous studies [27, 34]. Surprisingly, we found that the MRSP ST71 isolated from a small animal dermatologist in Italy [12] was the best strain adhering to both canine and human corneocytes. This finding suggests that MRSP ST71 may be able to adapt to human skin, as supported by the frequent reports of this lineage among veterinarians and pet owners [12, 13], and in human infections [17]. The possible extended host spectrum of this lineage is indirectly suggested by the increasing number of reports of MRSP ST71 isolated from other animal species other than Canidae such as horses [7], donkeys [7], cats [7, 35], cattle [36], and parrots [7]. Similarly, a broad host range has been hypothesized for some methicillin-resistant S. aureus clones of animal origin such as ST398 [37].

We screened all seven strains used in the in vitro assay by PCR for the 18 putative CWAPs previously described by Bannoehr et al. [19] to identify any specific CWAP or combinations of CWAPs that may explain any differences in the adherence ability observed for the different strains. We did not observe a clear association between the presence of any particular CWAP or a combination of them and the enhanced adherence to corneocytes. For example, the MRSP ST68 strain, USA 06–3228, and the MRSP ST71 strains, E140 and Franca 29a, had the same CWA surface proteins profile, but exhibited great variability in the adherence ability to canine and human corneocytes. However it should be noted that we only PCR screened for the presence of these CWAP genes and adherence may be related to differential CWA protein expression that could be affected at the post-transcriptional and post-translational level or by degradation proteases [32]. In addition, the 18 putative CWAPs were identified based on in silico analysis of only one methicillin-susceptible S. pseudintermedius strain genome (ED99). Our strains may contain other CWAPs not present in ED99 or the adherence to canine corneocytes may be mediated by non-proteinaceous adhesins like wall teichoic acids, as shown for S. aureus adherence to nasal epithelial cells [38].

S. pseudintermedius adherence did not differ significantly between the corneocytes collected from dog testing negative for S. pseudintermedius and those collected from the four positive dogs. This result is apparently in contrast with the findings of a previous study, where it was demonstrated that in vitro adherence of S. pseudintermedius to canine corneocytes is influenced by the carrier status of corneocyte donors [39]. However, this is only an apparent contrast since we could only determine whether the donors were positive at the time of sampling. Determination of their actual carrier status would have required a longitudinal study setup [23, 39]. For example, the dog that tested negative for S. pseudintermedius at the time of sampling was not necessarily a non-carrier and could be sporadic or intermittent carrier according to the classification proposed by Paul et al. [23].

There are two major limitations in this study. First, the limited number of strains used in this study may reflect strain-dependent than group-dependent factors. Unfortunately it is not feasible to perform the adherence corneocytes assay using a larger number of strains due to the limited number of corneocytes adhesive discs that can be collected from a single donor at the same time. Second, our results are based on the mean adherence of ten different microscopic field images, and biological replicates from the same donor were not performed. However, “donor” was not a unit of concern and the corneocytes adherence assay was shown to be reproducible by the pilot experiment as well as by previous studies [27, 28].

In conclusion, under in vitro conditions, MRSP ST71 adhered better to corneocytes compared to MRSP non-ST71 and MSSP. The enhanced adherence of ST71 may be a factor contributing to the epidemiological success of this MRSP lineage. Another notable finding was the remarkable ability of a human isolate of MRSP ST71 to adhere to human corneocytes, which confirms the hypothesis that this lineage may have higher ability to adapt to humans and ultimately possess extended host range and higher zoonotic potential compared to other lineages of the bacterial species [12]. Further studies using a combined approach based on whole genome sequencing, proteomics and functional assays are needed to elucidate the genetic factors responsible for the enhanced in vitro adherence of MRSP ST71.

References

Bannoehr J, Guardabassi L: Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in the dog: taxonomy, diagnostics, ecology, epidemiology and pathogenicity. Vet Dermatol. 2012, 23: 253-266.

Gortel K, Campbell KL, Kakoma I, Whittem T, Schaeffer DJ, Weisiger RM: Methicillin resistance among staphylococci isolated from dogs. Am J Vet Res. 1999, 60: 1526-1530.

Loeffler A, Linek M, Moodley A, Guardabassi L, Sung JM, Winkler M, Weiss R, Lloyd DH: First report of multiresistant, mecA-positive Staphylococcus intermedius in Europe: 12 cases from a veterinary dermatology referral clinic in Germany. Vet Dermatol. 2007, 18: 412-421.

Bardiau M, Yamazaki K, Ote I, Misawa N, Mainil JG: Characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolated from dogs and cats. Microbiol Immunol. 2013, 57: 496-501.

Feng Y, Tian W, Lin D, Luo Q, Zhou Y, Yang T, Deng Y, Liu YH, Liu JH: Prevalence and characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in pets from South China. Vet Microbiol. 2012, 160: 517-524.

Perreten V, Kadlec K, Schwarz S, Grönlund Andersson U, Finn M, Greko C, Moodley A, Kania SA, Frank LA, Bemis DA, Franco A, Iurescia M, Battisti A, Duim B, Wagenaar JA, van Duijkeren E, Weese JS, Fitzgerald JR, Rossano A, Guardabassi L: Clonal spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in Europe and North America: an international multicentre study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010, 65: 1145-1154.

Ruscher C, Lübke-Becker A, Semmler T, Wleklinski CG, Paasch A, Soba A, Stamm I, Kopp P, Wieler LH, Walther B: Widespread rapid emergence of a distinct methicillin- and multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (MRSP) genetic lineage in Europe. Vet Microbiol. 2010, 144: 340-346.

Wang Y, Yang J, Logue CM, Liu K, Cao X, Zhang W, Shen J, Wu C: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolated from canine pyoderma in North China. J Appl Microbiol. 2012, 112: 623-630.

Osland AM, Vestby LK, Fanuelsen H, Slettemeås JS, Sunde M: Clonal diversity and biofilm-forming ability of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012, 67: 841-848.

Singh A, Walker M, Rosseau J, Weese JS: Characterization of the biofilm forming ability of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius from dog. BMC Vet Res. 2013, 9: 93-

Morris DO, Boston RC, O’Shea K, Rankin SC: The prevalence of carriage of meticillin-resistant staphylococci by veterinary dermatology practice staff and their respective pets. Vet Dermatol. 2010, 21: 400-407.

Paul NC, Moodley A, Ghibaudo G, Guardabassi L: Carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in small animal veterinarians: indirect evidence of zoonotic transmission. Zoonoses Public Health. 2011, 58: 533-539.

Laarhoven LM, de Heus P, van Luijn J, Duim B, Wagenaar JA, van Duijkeren E: Longitudinal study on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in households. PLoS One. 2011, 6: e27788-

Van Duijkeren E, Kamphuis M, van der Mije IC, Laarhoven LM, Duim B, Wagenaar JA, Houwers DJ: Transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius between infected dogs and cats and contact pets, humans and the environment in households and veterinary clinics. Vet Microbiol. 2011, 150: 338-343.

Kempker R, Mangalat D, Kongphet-Tran T, Eaton M: Beware of the pet dog: a case of Staphylococcus intermedius infection. Am J Med Sci. 2009, 338: 425-427.

Savini V, Barbarini D, Polakowska K, Gherardi G, Bialecka A, Kasprowicz A, Polilli E, Marrollo R, Di Bonaventura G, Fazii P, D'Antonio D, Miedzobrodzki J, Carretto E: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius infection in a bone marrow transplant recipient. J Clin Microbiol. 2013, 51: 1636-1638.

Stegmann R, Burnens A, Maranta CA, Perreten V: Human infection associated with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius ST71. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010, 65: 2047-2048.

Clarke SR, Foster SJ: Surface adhesins of Staphylococcus aureus. Adv Microb Physiol. 2006, 51: 187-224.

Bannoehr J, Ben Zakour NL, Reglinski M, Inglis NF, Prabhakaran S, Fossum E, Smith DG, Wilson GJ, Cartwright RA, Haas J, Hook M, van den Broek AH, Thoday KL, Fitzgerald JR: Genomic and surface proteinomic analysis of the canine pathogen Staphylococcus pseudintermedius reveals proteins that mediate adherence to the extracellular matrix. Infect Immun. 2011, 79: 3074-3086.

Bannoehr J, Brown JK, Shaw DJ, Fitzgerald RJ, van den Broek AH, Thoday KL: Staphylococcus pseudintermedius surface proteins SpsD and SpsO mediate adherence to ex vivo canine corneocytes. Vet Dermatol. 2012, 23: 119-124.

Pietrocola G, Geoghegan JA, Rindi S, Di Poto A, Missineo A, Consalvi V, Foster TJ, Speziale P: Molecular characterization of the multiple interactions of SpsD, a surface protein from Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, with host extracellular matrix proteins. PLoS One. 2013, 8: e66901-

Solyman SM, Black CC, Duim B, Perreten V, van Duijkeren E, Wagenaar JA, Eberlein LC, Sadeghi LN, Videla R, Bemis DA, Kania SA: Multilocus sequence typing for characterization of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. J Clin Microbiol. 2013, 51: 306-310.

Paul NC, Bärgman SC, Moodley A, Nielsen SS, Guardabassi L: Staphylococcus pseudintermedius colonization patterns and strain diversity in healthy dogs: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Vet Microbiol. 2012, 160: 420-427.

Damborg P, Moodley A, Guardabassi L: High genetic diversity among methicillin-resitant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolated from canine infection in Denmark. Proceeding of the 3rd ASM-ESCMID Conference in Methicillin-resistant Staphylococci in Animals: 4–7 November, Copenhagen, Denmark. Edited by: American Society for Microbiology. 2013, 80-

Ben Zakour NL, Bannoehr J, van den Broek AH, Thoday KL, Fitzgerald JR: Complete genome sequence of the canine pathogen Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. J Bacteriol. 2011, 193: 2363-2364.

Guardabassi L, Loeber ME, Jacobson A: Transmission of multiple antimicrobial-resistant Staphylococcus intermedius between dogs affected by deep pyoderma and their owners. Vet Microbiol. 2004, 98: 23-27.

Lu YF, McEwan NA: Staphylococcal and micrococcal adherence to canine and feline corneocytes: quantification using a simple adherence assay. Vet Dermatol. 2007, 18: 29-35.

Moodley A, Espinosa-Gongora C, Nielsen SS, McCarthy AJ, Lindsay JA, Guardabassi L: Comparative host specificity of human- and pig- associated Staphylococcus aureus clonal lineages. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e49344-

Quitoco IM, Ramundo MS, Silva-Carvalho MC, Souza RR, Beltrame CO, de Oliveira TF, Araújo R, Del Peloso PF, Coelho LR, Figueiredo AM: First report in South America of companion animal colonization by the USA1100 clone of community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (ST30) and by the European clone of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (ST71). BMC Res Notes. 2013, 6: 336-

Lowy FD: Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 1998, 339: 520-532.

Pöhlmann-Dietze P, Ulrich M, Kiser KB, Döring G, Lee JC, Fournier JM, Botzenhart K, Wolz C: Adherence of Staphylococcus aureus to endothelial cells: influence of capsular polysaccharide, global regulator agr, and bacterial growth phase. Infect Immun. 2000, 68: 4865-4871.

Ythier M, Resch G, Waridel P, Panchaud A, Gfeller A, Majcherczyk P, Quadroni M, Moreillon P: Proteomic and transcriptomic profiling of Staphylococcus aureus surface LPXTG-proteins: correlation with agr genotypes and adherence phenotypes. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012, 11: 1123-1139.

Georghegan JA, Monk IR, O’Gara JP, Foster TJ: Subdomains N2N3 of Fibronectin Binding Protein A mediate Staphylooccus aureus biofilm formation and adherence to fibrinogen using distinct mechanisms. J Bacteriol. 2013, 195: 2675-2683.

Woolley KL, Kelly RF, Fazakerley J, Williams NJ, Nuttall TJ, McEwan NA: Reduced in vitro adherence of Staphylococcus species to feline corneocytes compared to canine and human corneocytes. Vet Dermatol. 2008, 19: 1-6.

Kadlec K, Schwarz S, Perreten V, Andersson UG, Finn M, Greko C, Moodley A, Kania SA, Frank LA, Bemis DA, Franco A, Iurescia M, Battisti A, Duim B, Wagenaar JA, van Duijkeren E, Weese JS, Fitzgerald JR, Rossano A, Guardabassi L: Molecular analysis of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius of feline origin from different European countries and North America. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010, 65: 1826-1828.

Pilla R, Bonura C, Malvisi M, Snel GG, Piccinini R: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius as causative agent of dairy cow mastitis. Vet Rec. 2013, 173: 19-

McCarthy AJ, Lindsay JA, Loeffler A: Are all meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) equal in all hosts? Epidemiological and genetic comparison between animal and human MRSA. Vet Dermatol. 2012, 23: 267-275.

Weidenmaier C, Kokai-Kun JF, Kristian SA, Chanturiya T, Kalbacher H, Gross M, Nicholson G, Neumeister B, Mond JJ, Peschel A: Role of teichoic acids in Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization, a major risk factor in nosocomial infections. Nat Med. 2004, 10: 243-245.

Paul NC, Latronico F, Moodley A, Nielsen SS, Damborg P, Guardabassi L: In vitro adherence of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius to canine corneocytes is influenced by colonization status of corneocytes donors. Vet Res. 2013, 8: 44-52.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the human volunteers and the dogs’ owners for giving us permission to collect the corneocytes, to J. Ross Fitzgerald (The Roslin Institute, University of Edinburgh, Scotland) and Stephen A. Kania (College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Tennessee, US) for providing ED99 and USA 06–3228 respectively, to Dafni Paspaliari (University of Copenhagen, Denmark) and Ida Thøfner (University of Copenhagen, Denmark) for the constructive discussion and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: FL, AM, LG. Performed the experiments: FL. Analyzed the data: FL, SSN. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: FL, SSN, LG. Wrote and approved the final manuscript: FL, AM, SSN, LG.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Latronico, F., Moodley, A., Nielsen, S.S. et al. Enhanced adherence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius sequence type 71 to canine and human corneocytes. Vet Res 45, 70 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1297-9716-45-70

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1297-9716-45-70