Abstract

Background

To assess the retinal sensitivity in obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) patients evaluated with standard automated perimetry (SAP). And to correlate the functional SAP results with structural parameters obtained with optical coherence tomography (OCT).

Methods

This prospective, observational, case-control study consisted of 63 eyes of 63 OSAHS patients (mean age 51.7 ± 12.7 years, best corrected visual acuity ≥20/25, refractive error less than three spherical or two cylindrical diopters, and intraocular pressure < 21 mmHg) who were enrolled and compared with 38 eyes of 38 age-matched controls. Peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness was measured by Stratus OCT and SAP sensitivities and indices were explored with Humphrey Field Analyzer perimeter. Correlations between functional and structural parameters were calculated, as well as the relationship between ophthalmologic and systemic indices in OSAHS patients.

Results

OSAHS patients showed a significant reduction of the sensitivity for superior visual field division (p = 0.034, t-student test). When dividing the OSAHS group in accordance with the severity of the disease, nasal peripapillary RNFL thickness was significantly lower in severe OSAHS than that in controls and mild-moderate cases (p = 0.031 and p = 0.016 respectively, Mann-Whitney U test). There were no differences between groups for SAP parameters.

We found no correlation between structural and functional variables. The central visual field sensitivity of the SAP revealed a poor Pearson correlation with the apnea-hipopnea index (0.284, p = 0.024).

Conclusions

Retinal sensitivity show minor differences between healthy subjects and OSAHS. Functional deterioration in OSAHS patients is not easy to demonstrate with visual field examination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) is a disorder characterized by brief episodes of complete or partial upper airway collapse during sleep. When those apnea-hypopnea events sum five or more events per hour, a pathological breathing status appears. Numerous ophthalmological disorders seem to be associated with OSAHS, including floppy-eyelid syndrome or central serous chorioretinopathy. Moreover, some authors suggest that certain optic nerve (ON) disorders such as papilledema, glaucoma or non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy showed an increased incidence in the obstructive disease [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10].

Changes in the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness have been reported in OSAHS by multiple authors. These alterations appear even in individuals in whom glaucomatous neuropathy has been ruled out, proposing therefore the breathing disease could be “per se” an aggressive agent for the ON [11,12,13,14,15,16].

Studies describing the progression of the most common neuropathy in our specialty, glaucomatous neuropathy, have contributed to establish a relationship between the functional visual impairment and the structural damage of the ON [17, 18]. Other pathologies, as sclerosis multiple, also seem to have a good agreement and correlation between abnormalities detected by standard automated perimetry (SAP) and RNFL measurements, as Cheng et al. found in eyes with optic neuritis secondary to this cause [19].

The aim of this study was to investigate whether there is a visual field (VF) functional deficit in OSAHS patients compared to healthy individuals. And to study if there is a correlation between functional variables and structural (OCT) variables in OSAHS.

Methods

Eighty OSAHS patients were consecutively recruited in the Otolaryngology Department at the Hospital Miguel Servet, in Zaragoza, Spain. All patients had a newly discovered and previously untreated mild to severe OSAHS according to clinical features and apnea–hypopnea index (AHI) greater than 4. Before OSAHS was confirmed, patients completed a questionnaire concerning epidemiological data and information about symptoms such as loud snoring, observed apnea, or excessive daytime sleepiness. The most common vascular risk factors were studied and treated if necessary.

Patients were subsequently referred for an ophthalmological examination to the Ophthalmology Department at the Hospital Clínico Lozano Blesa in Zaragoza, Spain, between December 2010 and March 2012. Patients with history of stroke with central apnea, chronic uveitis, antiglaucomatous drug usage, optic neuropathy, ocular trauma or surgeries were excluded from this study. After appropriate information, written informed consent of all subjects was obtained. The research followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee.

The control group included 40 age-matched healthy subjects, who were recruited among relatives and employees at the Hospital Lozano Blesa. Selection was made with Berlin questionnaire (evaluating the functional signs of OSAHS, 86% sensitivity for diagnosis and 77% specificity) [20, 21]. Epidemiological data were collected and smoking habit and vascular risk factors were treated in the same way.

All OSAHS and controls underwent a complete ophthalmologic examination, including best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), ocular motility, slit-lamp biomicroscopy, Goldmann applanation tonometry, gonioscopy, Humphrey automated VF, and OCT examination. Values of the right eyes were selected for analysis except when they did not fulfill the inclusion criteria; in this case, left eyes were selected.

At least two reliable SAP were performed to minimize the learning effect. VFs were evaluated with a Humphrey Field Analyzer perimeter model 740i (Zeiss Humphrey Systems, Dublin, CA) by using the 24–2 SITA fast strategy, with a Goldman size III stimulus on a 31.5-apostilb background. Near addition was added to the subject’s refractive correction. If fixation losses were higher than 20% or false positive or false-negative rates were higher than 15%, the test was repeated. Each perimetry was performed on different days to avoid the fatigue effect and the same experienced examiner conducted all scans.

OCT was performed with the Stratus OCT (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA, USA) following 1% tropicamide instillation. Only high-quality images were included. Each patient underwent scans to measure peripapillary RNFL thickness, which was automatically calculated by the fast RNFL algorithm. We considered the overall thickness and per quadrant.

Examiners were masked to the diagnosis. All participants had a BCVA of 20/30 or better, with a refractive error lower than three spherical or two cylindrical diopters. Intraocular pressure (IOP) > 21 mmHg, posterior segment pathology or patients with media opacification were excluded. Regarding VF, eyes with defects compatible with glaucoma (nasal step, paracentral or arcuate scotomas, or arcuate blind spot enlargement) with a pattern standard deviation (PSD) significantly elevated beyond the 5% level and/or a Glaucoma Hemifield Test outside normal limits were also excluded.

For comparison we used Humphrey global indices such as mean deviation (MD) and PSD, and we also calculated mean sensitivity (MS) recording each of the threshold values in decibel scale. Sector MD was calculated by averaging the deviation values on total-deviation plots for each sector. To investigate correspondence between structure and function, we used a more simplified version of the topographic map obtained by Garway-Heath [17], proposed by Cheng et al. [19]. Nevertheless, we introduced some subtle variations on Cheng’s map, like the use of all sensitivity points, including the blind spot ones (Fig. 1).

Corresponding areas: visual field – optic nerve. a Cheng et al. map. Correlation between OCT RNFL quadrants and corresponding sectors on SAP 24–2. b Topographical division on map of absolute retinal sensitivity used in our study, based on the topographic map proposed by Cheng et al. Note the inclusion of the points corresponding to the blind spot in the central division average sensitivity calculations

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed by using Statistical Package for Social Sciences software (version 19.0, Chicago, IL, USA). Values were presented as mean ± standard deviation, and expressed in microns for the peripapillary RNFL thickness and in decibels for the VF sensitivities. Qualitative differences between the studied variables were assessed by using Pearson’s chi-squared test.

Differences between controls and OSAHS were tested by Student’s-t test when normality and equality of variances were proved. If these conditions were not satisfied, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used.

In a second analysis, OSAHS sample was divided according to severity into two groups: those with mild-moderate OSAHS (group 1, AHI ≥5 and < 30) and those with severe OSAHS (group 2, AHI ≥30). Both groups were compared to controls. Quantitative differences between the three groups were compared by using one-way ANOVA test, once normality and homogeneity was proved with Shapiro-Wilk and Levene’s tests. In the event of breach of the homogeneity and normality assumption, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis H test was applied. In those cases where differences had been statistically significant, two by two Scheffé comparison (after ANOVA test) or Mann-Whitney U analysis (after Kruskal-Wallis H test) were performed to know which groups were different.

The relationship between structural and functional variables were analyzed by applying linear, logarithmic, inverse, quadratic and cubic models in OSAHS and in controls separately. In addition, Pearson’s correlation coefficient between AHI and VF indices in OSAHS were evaluated. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 80 consecutive OSAHS who accepted to participate, 63 patients (66.9%) were included in the study (51 right eyes and 12 left eyes), whereas 36 patients (33.1%) were excluded. Twenty-nine patients had a mild-moderate OSAHS (46%), and the other 34 patients (54%) had a severe disorder.

In the control group, 40 individuals classified as “low risk subjects” by the Berlin questionnaire were examined. Two patients were excluded after exclusion criteria application, and finally the group was composed of 37 right eyes and one left eye of 38 healthy subjects.

Age showed no statistically significant difference between groups, neither when dividing the OSAHS group according to its severity. In OSAHS group, although more men than women were enrolled, we did not consider this difference because gender has no effect on RNFL thickness as previously mentioned [22]. Body mass index was not matched, and was higher in OSAHS than that in controls (p < 0.001). Nevertheless, no significant differences in vascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidemia) and prevalence of smoking habit between cases and controls were found.

Table 1 shows the results of IOP, peripapillary RNFL thickness and VF parameters in controls and OSAHS. Differences between groups were just found in the VF superior division, sensitivity was higher in healthy subjects than in OSAHS ones. MD showed results close to the statistical significance.

Table 2 shows the results of IOP and peripapillary RNFL thickness measurements by dividing OSAHS patients according to severity. IOP showed no differences between groups. Nasal quadrant of peripapillary RNFL thickness showed a difference between categories. Thus, nasal RNFL thickness was significantly lower in severe OSAHS than that in moderate OSAHS (p = 0.031, Mann-Whitney U test). Moreover, nasal RNFL thickness was thinner in severe OSAHS versus controls (p = 0.016, Mann-Whitney U test).

Humphrey VF results showed no differences between controls and severity of OSAHS groups (Table 3). VF superior division showed a nonstatistical trend (0.08, ANOVA test). This difference was not statistically significant when we applied a multiple comparison test: p = 0.11 in controls versus mild-moderates; p = 0.295 in controls versus severes; and p = 0.834 in mild-moderates versus severes (Scheffé post hoc test).

A relationship between functional and structural ON parameters in both, OSAHS and controls, was not demonstrated. Table 4 shows linear, logarithmic, inverse, quadratic and cubic correlation models between linear parameters, as the thickness of peripapillary RNFL quadrants and parameters expressed in logarithmic scale such as VF sensitivities.

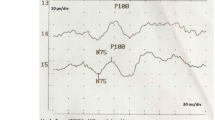

Only the central VF sensitivity of the SAP revealed a poor correlation with the AHI, with a Pearson’s correlation coefficient of 0.284 (p = 0.024, Fig. 2).

Discussion

The low oxygen levels during sleep lead to the adrenergic system activation, inflammation and procoagulant mechanisms prompting to endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress and metabolic deregulation [23]. This vascular phenomenon may compromise ON perfusion and oxygenation, ultimately leading to optic neuropathy [24, 25]. Several authors, including our own group, have published RNFL thickness variations in individuals with sleep apnea [11,12,13,14,15,16], which could be a consequence of vascular and gasometric alterations triggered by OSAHS.

Peripapillary RNFL thickness reflects neuronal axons, and would allow quantification of ganglion cell axonal loss [26]. Moreover, VF values estimates functional loss of the whole visual pathway, from retina to cortex [27]. VF maps show a correspondence with neuronal distribution of RNFL in the ON head, as Garway et al. demonstrated [17]. Therefore, theoretically, a correlation between OCT and VF parameters could be found. If this correspondence appears, both OCT and VF could be potentially used as biomarkers for neuronal degeneration in OSAHS patients.

Sensitivity of superior VF division was significantly lower in OSAHS patients than that in controls. This finding is not consistent with a significant change of inferior peripapillary RNFL thickness, which corresponds topographically with superior VF division and would justify the functional decline. Subtle edema secondary to vascular deregulation and increase in cerebrospinal fluid pressure [13, 28, 29] could explain the VF alterations found in our patients, and the fact that reduction in sensitivity is not associated with a decrease in RNFL thickness. As we previously suggested [14], it is possible that analysing all ranges of OSAHS severity together imply masking certain ON structural alterations. Theoretically, a first stage of edema and inflammation in mild and intermediate stages of the respiratory disease would precede an atrophy phase. We should, therefore, think that the biggest differences will be found in the most serious cases, where the decline of the RNFL will be triggered by longer exposure to hypoxia, and will be logical find higher degrees of atrophy. This fact is reflected in nasal quadrant RNFL thickness, where we found differences between severe OSAHS and the other groups. Another possible theory explaining the functional loss without structural alteration is the association of OSAHS with floppy eyelid syndrome [30,31,32]. A fatigue-related ptosis could reduce superior visual field acting as an artefact, as the ‘normal’ OCT inferior RNFL thickness confirms.

On the other hand, VF parameters showed no differences in the two by two comparisons between OSAHS groups and controls. This result contrasts with those obtained by other authors. Thus, Huseyinoglu et al. [13] found higher PSD and lower MD values in OSAHS patients comparing to controls. Xin et al. and Tsang et al. [29, 33] found affected values of MD and PSD in OSAHS comparing with controls. Nevertheless, they did not exclude any case of glaucoma and that could generate a bias in their results. Ferrandez et al. [34] found a generalized decrease in retinal sensitivity without focal defects in OSAHS. Furthermore, they reported changes in MD, PSD and VFI values with worse scores in patients with apnea. Disparities between their results and ours could be justified by different examination strategies used. We have chosen a shorter VF strategy to explore the patients since we know that “fatigue effect” could modify VF outcomes [33, 35] and is more prevalent in OSAHS patients [36,37,38], even when the SAP reliability criteria were kept within normal limits. We could observe a considerable difficulty to some OSAHS patients to maintain the concentration for 4 to 8 min for VF completion. Because of this, we decided to perform SITA-fast strategies in the present study, in spite of this shorter algorithm is known to improve the mean defect and to be less precise compared to SITA standard [39]. It is likely that hypersomnia, which is one of the crucial symptoms of the disease, could act as a confounding factor during VF examination, obtaining lower sensitivity rates comparing to controls, especially in longer examinations.

Regarding structure-function analysis, the absence of a common scale for both measurements, logarithmic on one side (decibels) and decimal on the other one (microns or percentages), makes it difficult to draw a parallel relationship between both examinations. There is a controversy regarding the type of association between structural and functional variables. Thus, various publications assume a linear correlation when both parameters are expressed in a linear scale, and an exponential or curvilinear relationship when one of the variables is linear whereas the other one is expressed in a logarithmic scale [40, 41]. Conversely, other authors hardly found any differences between structure-function correlations when the latter was expressed in logarithmic or linear scale [42, 43]. Based on this, our research analyses the association applying linear and non-linear models.

Special interest would have the correlation between the nasal quadrant of RNFL thickness and temporal VF division, since we found statistically significant differences for the structural parameter. Relationship between RNFL thickness quantified with Stratus OCT and VF MD was better fitted with second-order polynomials than with a linear model in patients with glaucoma [41]. These regression models describe a curvilinear relationship, suggesting that progression of VF loss, when it is expressed in MD, increases during the course of the disease. This idea is compatible with the concept of “functional reserve”, i.e. there must be a significant structural damage to bring up a functional representation of the same in the VF [19, 44,45,46,47]. Therefore, the absence of correlation found in the present study may be a consequence of the perimetric exclusion criteria, by which all eyes with suggestive alterations of glaucomatous neuropathy were excluded from the analysis.

One of the strengths of our study is that we just included patients with normal IOP, normal gonioscopy, and no perimetric evidence of glaucomatous neuropathy, in order to assess a hypothetical reduction in retinal sensitivity produced exclusively by the respiratory disorder. In this way, we avoid biased results by the inclusion of glaucomatous patients, whose incidence, as we have already mentioned, is higher in patients suffering from apnea [7,8,9,10]. The main limitation of our study include the relatively small sample size, mainly when OSAHS were divided according to severity. Groups with larger number of patients could have shown some correlation between variables or more consistent conclusions.

Conclusions

In conclusion, due to the lack of association between variables and no significant differences in VF variables when dividing OSAHS patients, we cannot state that perimetry is a useful diagnostic tool to demonstrate functional deterioration in OSAHS. Moreover, future research should analyze the results obtained in patients with OSAHS prior and after effective treatment, to establish the real VF involvement in the apneic disorder.

Abbreviations

- AHI:

-

Apnea–hypopnea index

- BCVA:

-

Best-corrected visual acuity

- MD:

-

Mean deviation

- MS:

-

Mean sensitivity

- OCT:

-

Optical coherence tomography

- ON:

-

Optic nerve

- OSAHS:

-

Obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome

- PSD:

-

Pattern standard deviation

- RNFL:

-

Retinal nerve fiber layer

- SAP:

-

Standard automated perimetry

- VF:

-

Visual field

References

Karger RA, White WA, Park WC, et al. Prevalence of floppy eyelid syndrome in obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1669–74.

Leroux les Jardins G, Glacet-Bernard A, Lasry S, Housset B, Coscas G, Soubrane G. Retinal vein occlusion and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2009;32:420–4.

Jain AK, Kaines A, Schwartz S. Bilateral central serous chorioretinopathy resolving rapidly with treatment for obstructive sleep apnea. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010;248:1037–9.

Kloos P, Laube I, Thoelen. Obstructive sleep apnea in patients with central serous chorioretinopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246:1225–8.

Purvin VA, Kawasaki A, Yee RD. Papilledema and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:1626–30.

Palombi K, Renard E, Levy P, et al. Non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy is nearly systematically associated with obstructive sleep apnoea. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:879–82.

Mojon DS, Hess CW, Goldblum D, et al. High prevalence of glaucoma in patients with sleep apnea syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1009–12.

Mojon DS, Hess CW, Goldblum D, Böhnke M, Körner F, Mathis J. Primary open-angle glaucoma is associated with sleep apnea syndrome. Ophthalmologica. 2000;214:115–8.

Bendel RE, Kaplan J, Heckman M, Fredrickson PA, Lin SC. Prevalence of glaucoma in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea—a cross-sectional case-series. Eye (Lond). 2008;22:1105–9.

Faridi O, Park SC, Liebmann JM, Ritch R. Glaucoma and obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012;40:408–19.

Lin PW, Friedman M, Lin HC, Chang HW, Pulver TM, Chin CH. Decreased retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in patients with obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249:585–93.

Sagiv O, Fishelson-Arev T, Buckman G, et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measurements by optical coherence tomography in patients with sleep apnea syndrome. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;42:132–8.

Huseyinoglu N, Ekinci M, Ozben S, Buyukuysal C, Kale MY, Sanivar HS. Optic disc and retinal nerve fiber layer parameters as indicators of neurodegenerative brain changes in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep Breath. 2014;18:95–102.

Casas P, Ascaso FJ, Vicente E, Tejero-Garcés G, Adiego MI, Cristóbal JA. Retinal and optic nerve evaluation by optical coherence tomography in adults with obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS). Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251:1625–34.

Shiba T, Takahashi M, Sato Y, et al. Relationship between severity of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157:1202–8.

Kargi SH, Altin R, Koksal M, et al. Retinal nerve fibre layer measurements are reduced in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Eye (Lond). 2005;19:575–9.

Garway-Heath DF, Poinoosawmy D, Fitzke FW, Hitchings RA. Mapping the visual field to the optic disc in normal tension glaucoma eyes. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1809–15.

Ferreras A, Pablo LE, Garway-Heath DF, Fogagnolo P, García-Feijoo J. Mapping standard automated perimetry to the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:3018–25.

Cheng H, Laron M, Schiffman JS, Tang RA, Frishman LJ. The relationship between visual field and retinal nerve fiber layer measurements in patients with multiple sclerosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:5798–805.

Netzer NC, Stoohs RA, Netzer CM, Clark K, Strohl KP. Using the Berlin questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:485–91.

Sharma SK, Sinha S, Banga A, Pandey RM, Handa KK. Validation of the modified Berlin questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Indian J Med Res. 2006;124:281–90.

Bowd C, Zangwill LM, Blumenthal EZ, et al. Imaging of the optic disc and retinal nerve fiber layer: effects of age, optic disc area, refractive error and gender. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis. 2002;19:197–207.

Shahar E, Whitney CW, Redline S, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease: cross sectional results of the sleep heart health study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:19–25.

Anderson DR. Glaucoma, capillaries and pericytes. 1. Blood flow regulation. Ophthalmologica. 1996;210:257–62.

Karakucuk S, Goktas S, Aksu M, et al. Ocular blood flow in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS). Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246:129–34.

Budenz DL, Anderson DR, Varma R, et al. Determinants of normal retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measured by Stratus OCT. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1046–52.

Xie K, Liu CY, Hasso AN, Crow RW. Visual field changes as an early indicator of glioblastoma multiforme progression: two cases of functional vision changes before MRI detection. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:1041–7.

Bucci FA Jr, Krohel GB. Optic nerve swelling secondary to the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;105:428–30.

Xin C, Zhang W, Wang L, Yang D, Wang J. Changes of visual field and optic nerve fiber layer in patients with OSAS. Sleep Breath. 2015;19:129–34.

McNab AA. The eye and sleep apnea. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11:269–76.

West SD, Turnbull C. Eye disorders associated with obstructive sleep apnoea. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2016;22:595-601.

Leibovitch I, Selva D. Floppy eyelid syndrome: clinical features and the association with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med. 2006;7:117–22.

Tsang CS, Chong SL, Ho CK, Li MF. Moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnoea patients is associated with a higher incidence of visual field defect. Eye. 2006;20:38–42.

Ferrandez B, Ferreras A, Calvo P, et al. Retinal sensitivity is reduced in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:7119–25.

Gonzalez de la Rosa M, Pareja A. Influence of the “fatigue effect” on the mean deviation measurement in perimetry. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1997;7:29–34.

Jurádo-Gámez B, Guglielmi O, Gude-Sampedro F, Buela-Casal G. Effect of CPAP therapy on job productivity and psychosocial occupational health in patients with moderate to severe sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2015;19:1293–9.

Tippin J, Sparks J, Rizzo M. Visual vigilance in drivers with obstructive sleep apnea. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:143–51.

Bjornsdottir E, Keenan BT, Eysteinsdottir B, et al. Quality of life among untreated sleep apnea patients compared with the general population and changes after treatment with positive airway pressure. J Sleep Res. 2015;24:328–38.

Saunders LJ, Russell RA, Crabb DP. Measurement precision in a series of visual fields acquired by the standard and fast versions of the Swedish interactive thresholding algorithm: analysis of large-scale data from clinics. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:74–80.

Hood DC. Relating retinal nerve fiber thickness to behavioral sensitivity in patients with glaucoma: application of a linear model. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis. 2007;24:1426–30.

Leung CK, Chong KK, Chan WM, et al. Comparative study of retinal nerve fiber layer measurement by Stratus OCT and GDx VCC, II: structure/function regression analysis in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:3702–11.

Nilforushan N, Nassiri N, Moghimi S, et al. Structure-function relationships between spectral-domain OCT and standard achromatic perimetry. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:2740–8.

Bowd C, Zangwill LM, Medeiros FA, et al. Structure-function relationships using confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy, optical coherence tomography, and scanning laser polarimetry. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2889–95.

Ajtony C, Balla Z, Somoskeoy S, Kovacs B. Relationship between visual field sensitivity and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness as measured by optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:258–63.

Costello F, Coupland S, Hodge W, et al. Quantifying axonal loss after optic neuritis with optical coherence tomography. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:963–9.

Nouri-Mahdavi K, Hoffman D, Tannenbaum DP, Law SK, Caprioli J. Identifying early glaucoma with optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:228–35.

Bowd C, Weinreb RN, Williams JM, Zangwill LM. The retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in ocular hypertensive, normal, and glaucomatous eyes with optical coherence tomography. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:22–6.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

The authors certify that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to individual data protection but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PC acquired and analyzed the data. Moreover she wrote the main ideas of the work. FJA helped with the data interpretation. Moreover, he edited the final work. EV selected the OSAHS patients and acquired othorrinolaringologic data. GTG acquired the data and helped write the main ideas. MIA designed the work. JAC helped with the data interpretation. Moreover, he edited the final work. We confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved by all named authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee (Clinical Univeristary Hospital Lozano Blesa, Zaragoza).

Written informed consent for ophthalmological exploration and prospective data collection of all subjects was obtained at the ophthalmology department visit by the clinician examiner.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Casas, P., Ascaso, F.J., Vicente, E. et al. Visual field defects and retinal nerve fiber imaging in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and in healthy controls. BMC Ophthalmol 18, 66 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-018-0728-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-018-0728-z