Abstract

Let  denote the space of all holomorphic functions on the unit ball

denote the space of all holomorphic functions on the unit ball  . This paper investigates the following integral-type operator with symbol

. This paper investigates the following integral-type operator with symbol  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , where

, where  is the radial derivative of

is the radial derivative of  . We characterize the boundedness and compactness of the integral-type operators

. We characterize the boundedness and compactness of the integral-type operators  from general function spaces

from general function spaces  to Zygmund-type spaces

to Zygmund-type spaces  , where

, where  is normal function on

is normal function on  .

.

Similar content being viewed by others

1. Introduction

Let  be the open unit ball of

be the open unit ball of  , let

, let  be its boundary, and let

be its boundary, and let  be the family of all holomorphic functions on

be the family of all holomorphic functions on  . Let

. Let  and

and  be points in

be points in  and

and  .

.

Let

stand for the radial derivative of  . For

. For  , let

, let  , where

, where  is the Möbius transformation of

is the Möbius transformation of  satisfying

satisfying  ,

,  , and

, and  . For

. For  ,

,  , we say

, we say  provided that

provided that  and

and

The space  , introduced by Zhao in [1], is known as the general family of function spaces. For appropriate parameter values

, introduced by Zhao in [1], is known as the general family of function spaces. For appropriate parameter values  ,

, , and

, and  ,

,  coincides with several classical function spaces. For instance, let

coincides with several classical function spaces. For instance, let  be the unit disk in

be the unit disk in  ,

,  if

if  (see [2]), where

(see [2]), where  , consists of those analytic functions

, consists of those analytic functions  in

in  for which

for which

The space  is the classical Bergman space

is the classical Bergman space  (see [3]),

(see [3]),  is the classical Besov space

is the classical Besov space  , and, in particular,

, and, in particular,  is just the Hardy space

is just the Hardy space  . The spaces

. The spaces  are

are  spaces, introduced by Aulaskari et al. [4, 5]. Further,

spaces, introduced by Aulaskari et al. [4, 5]. Further,  , the analytic functions of bounded mean oscillation. Note that

, the analytic functions of bounded mean oscillation. Note that  is the space of constant functions if

is the space of constant functions if  . More information on the spaces

. More information on the spaces  can be found in [6, 7].

can be found in [6, 7].

Recall that the Bloch-type spaces (or  -Bloch space)

-Bloch space)  , consists of all

, consists of all  for which

for which

The little Bloch-type space  consists of all

consists of all  such that

such that

Under the norm introduced by  is a Banach space and

is a Banach space and  is a closed subspace of

is a closed subspace of  . If

. If  , we write

, we write  and

and  for

for  and

and  , respectively.

, respectively.

A positive continuous function  on the interval [0,1) is called normal if there are three constants

on the interval [0,1) is called normal if there are three constants  and

and  such that

such that

Let  denote the class of all

denote the class of all  such that

such that

Write

With the norm  ,

,  is a Banach space.

is a Banach space.  is called the Zygmund space (see [8]). Let

is called the Zygmund space (see [8]). Let  denote the class of all

denote the class of all  such that

such that

Let  be a normal function on [0,1). It is natural to extend the Zygmund space to a more general form, for an

be a normal function on [0,1). It is natural to extend the Zygmund space to a more general form, for an  , we say that

, we say that  belongs to the space

belongs to the space  if

if

It is easy to check that  becomes a Banach space under the norm

becomes a Banach space under the norm

and  will be called the Zygmund-type space.

will be called the Zygmund-type space.

Let  denote the class of holomorphic functions

denote the class of holomorphic functions  such that

such that

and  is called the little Zygmund-type space. When

is called the little Zygmund-type space. When  , from [8, page 261], we say that

, from [8, page 261], we say that  if and only if

if and only if  , and there exists a constant

, and there exists a constant  such that

such that

for all  and

and  , where

, where  is the ball algebra on

is the ball algebra on  .

.

For  , the following integral-type operator (so called extended Cesàro operator) is

, the following integral-type operator (so called extended Cesàro operator) is

where  and

and  . Stević [9] considered the boundedness of

. Stević [9] considered the boundedness of  on

on  -Bloch spaces. Lv and Tang got the boundedness and compactness of

-Bloch spaces. Lv and Tang got the boundedness and compactness of  from

from  to

to  -Bloch spaces for all

-Bloch spaces for all  (see [10]). Recently, Li and Stević discussed the boundedness of

(see [10]). Recently, Li and Stević discussed the boundedness of  from Bloch-type spaces to Zygmund-type spaces in [11]. For more information about Zygmund spaces, see [12, 13].

from Bloch-type spaces to Zygmund-type spaces in [11]. For more information about Zygmund spaces, see [12, 13].

In this paper, we characterize the boundedness and compactness of the operator  from general analytic spaces

from general analytic spaces  to Zygmund-type spaces.

to Zygmund-type spaces.

In what follows, we always suppose that  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  . Throughout this paper, constants are denoted by

. Throughout this paper, constants are denoted by  ; they are positive and may have different values at different places.

; they are positive and may have different values at different places.

2. Some Auxiliary Results

In this section, we quote several auxiliary results which will be used in the proofs of our main results. The following lemma is according to Zhang [14].

Lemma 2.1.

If  , then

, then  and

and

Lemma 2.2 (see [9]).

For  , if

, if  , then for any

, then for any

Lemma 2.3 (see [15]).

For every  , it holds

, it holds  .

.

Lemma 2.4 (see [10]).

Let  . Suppose that for each

. Suppose that for each  ,

,  -variable functions

-variable functions  satisfy

satisfy  , then

, then

Lemma 2.5.

Assume that  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  is a normal function on

is a normal function on  , then

, then  is compact if and only if

is compact if and only if  is bounded, and for any bounded sequence

is bounded, and for any bounded sequence  in

in  which converges to zero uniformly on compact subsets of

which converges to zero uniformly on compact subsets of  as

as  , one has

, one has  .

.

The proof of Lemma 2.5 follows by standard arguments (see, e.g., Lemma 3 in [16]). Hence, we omit the details.

The following lemma is similar to the proof of Lemma 1 in [17]. Hence, we omit it.

Lemma 2.6.

Let  be a normal function. A closed set

be a normal function. A closed set  in

in  is compact if and only if it is bounded and satisfies

is compact if and only if it is bounded and satisfies

3. Main Results and Proofs

Now, we are ready to state and prove the main results in this section.

Theorem 3.1.

Let  ,

,  ,

,  , and let

, and let  be normal,

be normal,  and

and  , then

, then  is bounded if and only if

is bounded if and only if

(i)for  ,

,

(ii)for  ,

,

Proof.

-

(i)

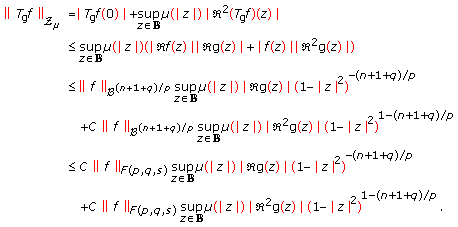

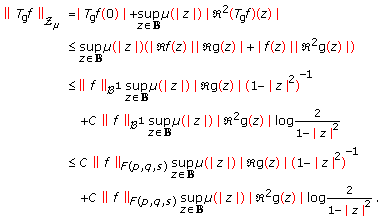

First, for

, suppose that

, suppose that  and

and  . By Lemmas 2.1–2.3, we write

. By Lemmas 2.1–2.3, we write  . We have that

. We have that  (3.5)

(3.5)

Hence, (3.1) and (3.2) imply that  is bounded.

is bounded.

Conversely, assume that  is bounded. Taking the test function

is bounded. Taking the test function  , we see that

, we see that  , that is,

, that is,

For  , set

, set

Then,  by [14] and

by [14] and  .

.

Hence,

From (3.8), we have

On the other hand, we have

Combing (3.9) and (3.10), we get (3.1).

In order to prove (3.2), let  and set

and set

It is easy to see that  ,

,  . We know that

. We know that  ; moreover, there is a positive constant

; moreover, there is a positive constant  such that

such that  . Hence,

. Hence,

From (3.1) and (3.12), we see that (3.2) holds.

-

(ii)

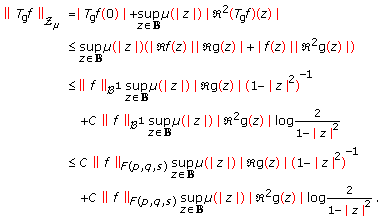

If

, then, by Lemmas 2.1 and 2.2, we have

, then, by Lemmas 2.1 and 2.2, we have  , for

, for  , we get

, we get  (3.13)

(3.13)

Applying (3.3) and (3.4) in (3.13), for the case  , the boundedness of the operator

, the boundedness of the operator  follows.

follows.

Conversely, suppose that  is bounded. Given any

is bounded. Given any  , set

, set

then  by [14].

by [14].

By the boundedness of  , it is easy to see that

, it is easy to see that

By (3.14) and (3.15), in the same way as proving (3.1), we get that (3.3) holds.

Now, given any  , set

, set

then  . Applying Lemma 2.4, we have that

. Applying Lemma 2.4, we have that  . Hence,

. Hence,

From (3.15) and (3.17), we see that (3.4) holds. The proof of this theorem is completed.

Theorem 3.2.

Let  ,

,  ,

,  , and let

, and let  be normal,

be normal,  and

and  , then the following statements are equivalent:

, then the following statements are equivalent:

(A) is compact;

is compact;

(B) is compact;

is compact;

(C)

-

(i)

for

,

,

-

(ii)

for

,

,

Proof.

(B) ⇒ (A). This implication is obvious.

(A) ⇒ (C). First, for the case  .

.

Suppose that the operator  is compact. Let

is compact. Let  be a sequence in

be a sequence in  such that

such that  . Denote

. Denote  , and set

, and set

It is easy to see that  for

for  and

and  uniformly on compact subsets of

uniformly on compact subsets of  as

as  . By Lemma 2.5, it follows that

. By Lemma 2.5, it follows that

By Lemma 2.3, we have

From (3.23) and (3.24), we obtain

which means that (3.18) holds.

Similarly, we take the test function

Then,  for

for  and

and  uniformly on compact subsets of

uniformly on compact subsets of  as

as  . we obtain that (3.20) holds for the case

. we obtain that (3.20) holds for the case  .

.

For proving (3.19), we set

then  , and

, and  converges to 0 uniformly on any compact subsets of

converges to 0 uniformly on any compact subsets of  as

as  . By Lemma 2.5, it yields

. By Lemma 2.5, it yields

Further, we have

From (3.25), (3.28), and (3.29), it follows that

which implies that (3.19) holds.

-

(ii)

Second, for the case

, take the test function

, take the test function  (3.31)

(3.31)

Then,  by Lemma 2.4 and

by Lemma 2.4 and  uniformly on any compact subset of

uniformly on any compact subset of  . By Lemma 2.5 and condition (

. By Lemma 2.5 and condition ( ), we have

), we have

Hence, we have that

From (3.20), (3.32), and (3.33), it follows that

which implies that (3.21) holds.

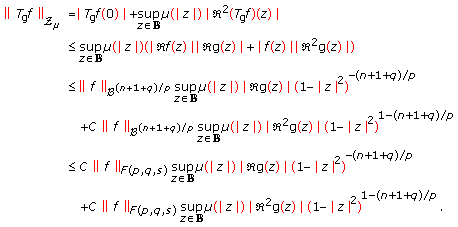

(C) ⇒ (B). Suppose that (3.18) and (3.19) hold for  . By Lemmas 2.1 and 2.2, we have that

. By Lemmas 2.1 and 2.2, we have that

Note that (3.18) and (3.19) imply that

Further, they also imply that (3.1) and (3.2) hold. From this and Theorem 3.1, it follows that set  is bounded. Using these facts, (3.18), and (3.19), we have

is bounded. Using these facts, (3.18), and (3.19), we have

Similarly, we obtain that (3.37) holds for the case  by (3.20) and (3.21). Exploiting Lemma 2.6, the compactness of the operator

by (3.20) and (3.21). Exploiting Lemma 2.6, the compactness of the operator  follows. The proof of this theorem is completed.

follows. The proof of this theorem is completed.

Finally, we consider the case  .

.

Theorem 3.3.

Let  ,

,  ,

,  , and let

, and let  be normal,

be normal,  ,

,  , then the following statements are equivalent:

, then the following statements are equivalent:

(A) is bounded;

is bounded;

(B) and

and

The proof of Theorem 3.3 follows by the proof of Theorem 3.1. So, we omit the details here.

Theorem 3.4.

Let  ,

,  ,

,  , and let

, and let  be normal,

be normal,  and

and  , then the following statements are equivalent:

, then the following statements are equivalent:

(A) is compact;

is compact;

(B) and

and

Proof.

(A) ⇒ (B). We assume that  is compact. For

is compact. For  , we obtain that

, we obtain that  . Exploiting the test function in (3.22), similarly to the proof of Theorem 3.2, we obtain that (3.39) holds. As a consequence, it follows that

. Exploiting the test function in (3.22), similarly to the proof of Theorem 3.2, we obtain that (3.39) holds. As a consequence, it follows that

(B) ⇒ (A). Assume that  is a sequence in

is a sequence in  such that

such that  , and

, and  uniformly on compact of

uniformly on compact of  as

as  . By Lemma 2.1 and [18, Lemma 4.2],

. By Lemma 2.1 and [18, Lemma 4.2],

From (3.39), we have that for every  , there is a

, there is a  , such that, for every

, such that, for every  ,

,

and from (3.39) that

Hence,

Since  on compact subsets of

on compact subsets of  by the Cauchy estimate, it follows that

by the Cauchy estimate, it follows that  on compact subsets of

on compact subsets of  , in particular on

, in particular on  . Taking in (3.44), the supremum over

. Taking in (3.44), the supremum over  , letting

, letting  , using the above-mentioned facts,

, using the above-mentioned facts,  , and since

, and since  is an arbitrary positive number, we obtain

is an arbitrary positive number, we obtain

Hence, by Lemma 2.5, the compactness of the operator  follows. The proof of this theorem is completed.

follows. The proof of this theorem is completed.

Theorem 3.5.

Let  ,

,  ,

,  , and let

, and let  be normal,

be normal,  and

and  , then the following statements are equivalent:

, then the following statements are equivalent:

(A) is compact;

is compact;

(B) and

and

Proof.

(A) ⇒ (B). For  , we obtain that

, we obtain that  . In the same way as in Theorem 3.4, we get that (3.46) holds.

. In the same way as in Theorem 3.4, we get that (3.46) holds.

(B) ⇒ (A). By Lemmas 2.1 and 2.2, we have that

This along with Theorem 3.2 implies that  is bounded. Taking the supremum over the unit ball in

is bounded. Taking the supremum over the unit ball in  , letting

, letting  in (3.46), using the condition (

in (3.46), using the condition ( ), and finally by applying Lemma 2.6, we get the compactness of the operator

), and finally by applying Lemma 2.6, we get the compactness of the operator  . This completes the proof of the theorem.

. This completes the proof of the theorem.

References

Zhao R: On a general family of function spaces. Annales Academiæ Scientiarum Fennicæ Mathematica Dissertationes 1996, (105):56.

Zhao R: On -Bloch functions and VMOA. Acta Mathematica Scientia. Series B 1996, 16(3):349–360.

Zhu KeHe: Operator Theory in Function Spaces, Monographs and Textbooks in Pure and Applied Mathematics. Volume 139. Marcel Dekker, New York, NY, USA; 1990:xii+258.

Aulaskari R, Lappan P: Criteria for an analytic function to be Bloch and a harmonic or meromorphic function to be normal. In Complex Analysis and Its Applications, Pitman Research Notes in Mathematics Series. Volume 305. Longman Scientific & Technical, Harlow, UK; 1994:136–146.

Aulaskari R, Xiao J, Zhao RH: On subspaces and subsets of BMOA and UBC. Analysis 1995, 15(2):101–121.

Pérez-González F, Rättyä J: Forelli-Rudin estimates, Carleson measures and -functions. Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications 2006, 315(2):394–414. 10.1016/j.jmaa.2005.10.034

Rättyä J: On some complex spaces and classes. Annales Academiæ Scientiarum Fennicæ Mathematica Dissertationes 2001, (124):73.

Zhu K: Spaces of Holomorphic Functions in the Unit Ball, Graduate Texts in Mathematics. Volume 226. Springer, New York, NY, USA; 2005:x+271.

Stević S: On an integral operator on the unit ball in. Journal of Inequalities and Applications 2005, (1):81–88.

Lv X, Tang X: Extended Cesàro operators from spaces to Bloch-type spaces in the unit ball. Korean Mathematical Society. Communications 2009, 24(1):57–66. 10.4134/CKMS.2009.24.1.057

Li S, Stević S: Integral-type operators from Bloch-type spaces to Zygmund-type spaces. Applied Mathematics and Computation 2009, 215(2):464–473. 10.1016/j.amc.2009.05.011

Li S, Stević S: Generalized composition operators on Zygmund spaces and Bloch type spaces. Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications 2008, 338(2):1282–1295. 10.1016/j.jmaa.2007.06.013

Li S, Stević S: Products of Volterra type operator and composition operator from and Bloch spaces to Zygmund spaces. Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications 2008, 345(1):40–52. 10.1016/j.jmaa.2008.03.063

Zhang XJ: Multipliers on some holomorphic function spaces. Chinese Annals of Mathematics. Series A. Shuxue Niankan. A Ji 2005, 26(4):477–486.

Hu Z: Extended Cesàro operators on mixed norm spaces. Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 2003, 131(7):2171–2179. 10.1090/S0002-9939-02-06777-1

Li SX, Stević S: Riemann-Stieltjes-type integral operators on the unit ball in . Complex Variables and Elliptic Equations 2007, 52(6):495–517. 10.1080/17476930701235225

Madigan K, Matheson A: Compact composition operators on the Bloch space. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 1995, 347(7):2679–2687. 10.2307/2154848

Tang X: Extended Cesàro operators between Bloch-type spaces in the unit ball of Cn. Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications 2007, 326(2):1199–1211. 10.1016/j.jmaa.2006.03.082

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Professor Rauno Aulaskari for his helpful suggestions. This research was supported in part by the Academy of Finland 121281.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, C. Integral-Type Operators from  Spaces to Zygmund-Type Spaces on the Unit Ball.

J Inequal Appl 2010, 789285 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/789285

Spaces to Zygmund-Type Spaces on the Unit Ball.

J Inequal Appl 2010, 789285 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/789285

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/789285

, suppose that

, suppose that  and

and  . By Lemmas 2.1–2.3, we write

. By Lemmas 2.1–2.3, we write  . We have that

. We have that

, then, by Lemmas 2.1 and 2.2, we have

, then, by Lemmas 2.1 and 2.2, we have  , for

, for  , we get

, we get

,

, ,

, , take the test function

, take the test function