Abstract

We consider the general solution of quartic functional equations and prove the Hyers-Ulam-Rassias stability. Moreover, using the pullbacks and the heat kernels we reformulate and prove the stability results of quartic functional equations in the spaces of tempered distributions and Fourier hyperfunctions.

Similar content being viewed by others

1. Introduction

One of the interesting questions concerning the stability problems of functional equations is as follows: when is it true that a mapping satisfying a functional equation approximately must be close to the solution of the given functional equation? Such an idea was suggested in 1940 by Ulam [1]. The case of approximately additive mappings was solved by Hyers [2]. In 1978, Rassias [3] generalized Hyers' result to the unbounded Cauchy difference. During the last decades, stability problems of various functional equations have been extensively studied and generalized by a number of authors (see [4–9]). The terminology Hyers-Ulam-Rassias stability originates from these historical backgrounds and this terminology is also applied to the cases of other functional equations. For instance, Rassias [10] investigated stability properties of the following functional equation

It is easy to see that  is a solution of (1.1) by virtue of the identity

is a solution of (1.1) by virtue of the identity

For this reason, (1.1) is called a quartic functional equation. Also Chung and Sahoo [11] determined the general solution of (1.1) without assuming any regularity conditions on the unknown function. In fact, they proved that the function  is a solution of (1.1) if and only if

is a solution of (1.1) if and only if  , where the function

, where the function  is symmetric and additive in each variable. Since the solution of (1.1) is even, we can rewrite (1.1) as

is symmetric and additive in each variable. Since the solution of (1.1) is even, we can rewrite (1.1) as

Lee et al. [12] obtained the general solution of (1.3) and proved the Hyers-Ulam-Rassias stability of this equation. Also Park [13] investigated the stability problem of (1.3) in the orthogonality normed space.

In this paper we consider the following quartic functional equation, which is a generalization of (1.3),

for fixed integer  with

with  . In the cases of

. In the cases of  in (1.4), homogeneity property of quartic functional equations does not hold. We dispense with this cases henceforth, and assume that

in (1.4), homogeneity property of quartic functional equations does not hold. We dispense with this cases henceforth, and assume that  . In Section 2, we show that for each fixed integer

. In Section 2, we show that for each fixed integer  with

with  , (1.4) is equivalent to (1.3). Moreover, using the idea of Găvruţa [14], we prove the Hyers-Ulam-Rassias stability of (1.4) in Section 3. Finally, making use of the pullbacks and the heat kernels, we reformulate and prove the Hyers-Ulam-Rassias stability of (1.4) in the spaces of some generalized functions such as

, (1.4) is equivalent to (1.3). Moreover, using the idea of Găvruţa [14], we prove the Hyers-Ulam-Rassias stability of (1.4) in Section 3. Finally, making use of the pullbacks and the heat kernels, we reformulate and prove the Hyers-Ulam-Rassias stability of (1.4) in the spaces of some generalized functions such as  of tempered distributions and

of tempered distributions and  of Fourier hyperfunctions in Section 4.

of Fourier hyperfunctions in Section 4.

2. General Solution of (1.4)

Throughout this section, we denote  and

and  by real vector spaces. It is well known [15] that a function

by real vector spaces. It is well known [15] that a function  satisfies the quadratic functional equation

satisfies the quadratic functional equation

if and only if there exists a unique symmetric biadditive function  such that

such that  for all

for all  . The biadditive function

. The biadditive function  is given by

is given by

Stability problems of quadratic functional equations can be found in [16–19]. Similarly, a function  satisfies the quartic functional equation (1.3) if and only if there exists a symmetric biquadratic function

satisfies the quartic functional equation (1.3) if and only if there exists a symmetric biquadratic function  such that

such that  for all

for all  (see [12]). We now present the general solution of (1.4) in the class of functions between real vector spaces.

(see [12]). We now present the general solution of (1.4) in the class of functions between real vector spaces.

Theorem 2.1.

A mapping  satisfies the functional equation (1.3) if and only if for each fixed integer

satisfies the functional equation (1.3) if and only if for each fixed integer  with

with  , a mapping

, a mapping  satisfies the functional equation (1.4).

satisfies the functional equation (1.4).

Proof.

Suppose that  satisfies (1.3). Putting

satisfies (1.3). Putting  in (1.3) we have

in (1.3) we have  . Also letting

. Also letting  in (1.3) we get

in (1.3) we get  . Using an induction argument we may assume that (1.4) is true for all

. Using an induction argument we may assume that (1.4) is true for all  with

with  . Replacing

. Replacing  by

by  and

and  by

by  in (1.4) we have

in (1.4) we have

Substituting  by

by  in (2.3) and using the evenness of

in (2.3) and using the evenness of  we get

we get

Adding (2.3) to (2.4) yields

According to the inductive assumption for  , (2.5) can be rewritten as

, (2.5) can be rewritten as

which proves the validity of (1.4) for  . For a negative integer

. For a negative integer  , replacing

, replacing  by

by  one can easily prove the validity of (1.4). Therefore (1.3) implies (1.4) for any fixed integer

one can easily prove the validity of (1.4). Therefore (1.3) implies (1.4) for any fixed integer  with

with  .

.

We now prove the converse. For each fixed integer  with

with  , we assume that

, we assume that  satisfies (1.4). Putting

satisfies (1.4). Putting  in (1.4) we have

in (1.4) we have  . Also letting

. Also letting  in (1.4) we get

in (1.4) we get  for all

for all  . Setting

. Setting  in (1.4) we obtain the homogeneity property

in (1.4) we obtain the homogeneity property  for all

for all  . Replacing

. Replacing  by

by  in (1.4) we have

in (1.4) we have

Interchanging  into

into  in (2.7) yields

in (2.7) yields

Replacing  and

and  by

by  and

and  in (1.4) we get

in (1.4) we get

Substituting  by

by  in (2.9) gives

in (2.9) gives

Plugging (2.7) into (2.8), and using (2.9) and (2.10) we have

Replacing  and

and  by

by  and

and  in (1.4), respectively, we get

in (1.4), respectively, we get

Setting  by

by  in (1.4) and dividing by

in (1.4) and dividing by  we obtain

we obtain

It follows from (2.12) and (2.13) that (2.11) can be rewritten in the form

Using an induction argument in (2.14), it is easy to see that  satisfies the following functional equation

satisfies the following functional equation

for each fixed integer  . Replacing

. Replacing  by

by  in (2.15), and comparing (1.4) with (2.15) we have

in (2.15), and comparing (1.4) with (2.15) we have  . Thus (2.14) implies (1.3). This completes the proof.

. Thus (2.14) implies (1.3). This completes the proof.

3. Stability of (1.4)

Now we are going to prove the Hyers-Ulam-Rassias stability for quartic functional equations. Let  be a real vector space and let

be a real vector space and let  be a Banach space.

be a Banach space.

Theorem 3.1.

Let  be a mapping such that

be a mapping such that

converges and

for all  . Suppose that a mapping

. Suppose that a mapping  satisfies the inequality

satisfies the inequality

for all  . Then there exists a unique quartic mapping

. Then there exists a unique quartic mapping  which satisfies quartic functional equation (1.4) and the inequality

which satisfies quartic functional equation (1.4) and the inequality

for all  . The mapping

. The mapping  is given by

is given by

for all  . Also, if for each fixed

. Also, if for each fixed  the mapping

the mapping  from

from  to

to  is continuous, then

is continuous, then  for all

for all  .

.

Proof.

Putting  in (3.3) and then dividing the result by

in (3.3) and then dividing the result by  we have

we have

which is rewritten as

for all  , where

, where  . Making use of induction arguments and triangle inequalities we have

. Making use of induction arguments and triangle inequalities we have

for all  . Now we prove the sequence

. Now we prove the sequence  is a Cauchy sequence. Replacing

is a Cauchy sequence. Replacing  by

by  in (3.8) and then dividing by

in (3.8) and then dividing by  we see that for

we see that for  ,

,

Since the right-hand side of (3.9) tends to  as

as  , the sequence

, the sequence  is a Cauchy sequence. Therefore we may define

is a Cauchy sequence. Therefore we may define

for all  . Replacing

. Replacing  by

by  , respectively, in (3.3) and then dividing by

, respectively, in (3.3) and then dividing by  we have

we have

Taking the limit as  , we verify that

, we verify that  satisfies (1.4) for all

satisfies (1.4) for all  . Now letting

. Now letting  in (3.8) we have

in (3.8) we have

for all  . To prove the uniqueness, let us assume that there exists another quartic mapping

. To prove the uniqueness, let us assume that there exists another quartic mapping  which satisfies (1.4) and the inequality (3.12). Obviously, we have

which satisfies (1.4) and the inequality (3.12). Obviously, we have  and

and  for all

for all  . Thus, we have

. Thus, we have

for all  . Letting

. Letting  , we must have

, we must have  for all

for all  . This completes the proof.

. This completes the proof.

Corollary 3.2.

Let  be fixed integer with

be fixed integer with  and let

and let  be real numbers such that

be real numbers such that  and either

and either  or

or  . Suppose that a mapping

. Suppose that a mapping  satisfies the inequality

satisfies the inequality

for all  . Then there exists a unique quartic mapping

. Then there exists a unique quartic mapping  which satisfies (1.4) and the inequality

which satisfies (1.4) and the inequality

for all  and for all

and for all  if

if  . The mapping

. The mapping  is given by

is given by

for all  .

.

Corollary 3.3.

Let  be fixed integer with

be fixed integer with  and

and  be a real number. Suppose that a mapping

be a real number. Suppose that a mapping  satisfies the inequality

satisfies the inequality

for all  . Then there exists a unique quartic mapping

. Then there exists a unique quartic mapping  defined by

defined by

which satisfies (1.4) and the inequality

for all  .

.

4. Stability of (1.4) in Generalized Functions

In this section, we reformulate and prove the stability theorem of the quartic functional equation (1.4) in the spaces of some generalized functions such as  of tempered distributions and

of tempered distributions and  of Fourier hyperfunctions. We first introduce briefly spaces of some generalized functions. Here we use the multi-index notations,

of Fourier hyperfunctions. We first introduce briefly spaces of some generalized functions. Here we use the multi-index notations,  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  , for

, for  ,

,  , where

, where  is the set of non-negative integers and

is the set of non-negative integers and  .

.

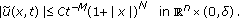

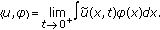

Definition 4.1 (see [20, 21]).

We denote by  the Schwartz space of all infinitely differentiable functions

the Schwartz space of all infinitely differentiable functions  in

in  satisfying

satisfying

for all  ,

,  , equipped with the topology defined by the seminorms

, equipped with the topology defined by the seminorms  . A linear form

. A linear form  on

on  is said to be tempered distribution if there is a constant

is said to be tempered distribution if there is a constant  and a nonnegative integer

and a nonnegative integer  such that

such that

for all  . The set of all tempered distributions is denoted by

. The set of all tempered distributions is denoted by  .

.

Imposing growth conditions on  in (4.1) a new space of test functions has emerged as follows.

in (4.1) a new space of test functions has emerged as follows.

Definition 4.2 (see [22]).

We denote by  the Sato space of all infinitely differentiable functions

the Sato space of all infinitely differentiable functions  in

in  such that

such that

for some positive constants  depending only on

depending only on  . We say that

. We say that  as

as  if

if  as

as  for some

for some  , and denote by

, and denote by  the strong dual of

the strong dual of  and call its elements Fourier hyperfunctions.

and call its elements Fourier hyperfunctions.

It can be verified that the seminorms (4.3) are equivalent to

for some constants  . It is easy to see the following topological inclusions:

. It is easy to see the following topological inclusions:

From the above inclusions it suffices to say that we consider (1.4) in the space  . Note that (3.14) itself makes no sense in the spaces of generalized functions. Following the notions as in [23–25], we reformulate the inequality (3.14) as

. Note that (3.14) itself makes no sense in the spaces of generalized functions. Following the notions as in [23–25], we reformulate the inequality (3.14) as

where  . Here

. Here  denotes the pullbacks of generalized functions. Also

denotes the pullbacks of generalized functions. Also  denotes the Euclidean norm and the inequality

denotes the Euclidean norm and the inequality  in (4.6) means that

in (4.6) means that  for all test functions

for all test functions  defined on

defined on  . We refer to (see [20, Chapter VI]) for pullbacks and to [21, 23–26] for more details of

. We refer to (see [20, Chapter VI]) for pullbacks and to [21, 23–26] for more details of  and

and  .

.

If  , the right side of (4.6) does not define a distribution. Thus, the inequality (4.6) makes no sense in this case. Also, if

, the right side of (4.6) does not define a distribution. Thus, the inequality (4.6) makes no sense in this case. Also, if  , it is not known whether Hyers-Ulam-Rassias stability of (1.4) holds even in the classical case. Thus, we consider only the case

, it is not known whether Hyers-Ulam-Rassias stability of (1.4) holds even in the classical case. Thus, we consider only the case  or

or  .

.

In order to prove the stability problems of quartic functional equations in the space of  we employ the

we employ the  -dimensional heat kernel, that is, the fundamental solution

-dimensional heat kernel, that is, the fundamental solution  of the heat operator

of the heat operator  in

in  given by

given by

Since for each  ,

,  belongs to

belongs to  , the convolution

, the convolution

is well defined for each  , which is called the Gauss transform of

, which is called the Gauss transform of  . In connection with the Gauss transform it is well known that the semigroup property of the heat kernel

. In connection with the Gauss transform it is well known that the semigroup property of the heat kernel

holds for convolution. Semigroup property will be useful to convert inequality (3.3) into the classical functional inequality defined on upper-half plane. Moreover, the following result called heat kernel method holds [27].

Let  . Then its Gauss transform

. Then its Gauss transform  is a

is a  -solution of the heat equation

-solution of the heat equation

satisfying

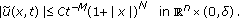

-

(i)

There exist positive constants

and

and  such that

such that (411)

(411) -

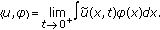

(ii)

as

as  in the sense that for every

in the sense that for every  ,

, (412)

(412)

Conversely, every  -solution

-solution  of the heat equation satisfying the growth condition (4.11) can be uniquely expressed as

of the heat equation satisfying the growth condition (4.11) can be uniquely expressed as  for some

for some  . Similarly, we can represent Fourier hyperfunctions as initial values of solutions of the heat equation as a special case of the results (see [28]). In this case, the estimate (4.11) is replaced by the following.

. Similarly, we can represent Fourier hyperfunctions as initial values of solutions of the heat equation as a special case of the results (see [28]). In this case, the estimate (4.11) is replaced by the following.

For every  there exists a positive constant

there exists a positive constant  such that

such that

We note that the Gauss transform

is well defined and  locally uniformly as

locally uniformly as  . Also

. Also  satisfies semi-homogeneity property

satisfies semi-homogeneity property

for all  .

.

We are now in a position to state and prove the main result of this paper.

Theorem 4.3.

Let  be fixed integer with

be fixed integer with  and let

and let  be real numbers such that

be real numbers such that  and either

and either  or

or  . Suppose that

. Suppose that  in

in  or

or  satisfies the inequality (4.6). Then there exists a unique quartic mapping

satisfies the inequality (4.6). Then there exists a unique quartic mapping  which satisfies (1.4) and the inequality

which satisfies (1.4) and the inequality

where  .

.

Proof.

Define  . Convolving the tensor product

. Convolving the tensor product  of

of  -dimensional heat kernels in

-dimensional heat kernels in  we have

we have

On the other hand, we figure out

and similarly we get

where  is the Gauss transform of

is the Gauss transform of  . Thus, inequality (4.6) is converted into the classical functional inequality

. Thus, inequality (4.6) is converted into the classical functional inequality

for all  . In view of (4.20), it can be verified that

. In view of (4.20), it can be verified that

exists.

We first prove the case  . Choose a sequence

. Choose a sequence  of positive numbers which tends to

of positive numbers which tends to  as

as  such that

such that  as

as  . Letting

. Letting  ,

,  in (4.20) and dividing the result by

in (4.20) and dividing the result by  we get

we get

which is written in the form

for all  , where

, where  . By virtue of the semi-homogeneous property of

. By virtue of the semi-homogeneous property of  , substituting

, substituting  by

by  , respectively, in (4.23) and dividing the result by

, respectively, in (4.23) and dividing the result by  we obtain

we obtain

Using induction arguments and triangle inequalities we have

for all  . Let us prove the sequence

. Let us prove the sequence  is convergent for all

is convergent for all  . Replacing

. Replacing  by

by  , respectively, in (4.25) and dividing the result by

, respectively, in (4.25) and dividing the result by  we see that

we see that

Letting  , we have

, we have  is a Cauchy sequence. Therefore we may define

is a Cauchy sequence. Therefore we may define

for all  . On the other hand, replacing

. On the other hand, replacing  by

by  in (4.20), respectively, and then dividing the result by

in (4.20), respectively, and then dividing the result by  we get

we get

Now letting  we see by definition of

we see by definition of  that

that  satisfies

satisfies

for all  . Letting

. Letting  in (4.25) yields

in (4.25) yields

To prove the uniqueness of  , we assume that

, we assume that  is another function satisfying (4.29) and (4.30). Setting

is another function satisfying (4.29) and (4.30). Setting  and

and  in (4.29) we have

in (4.29) we have

for all  . Then it follows from (4.30) and (4.31) that

. Then it follows from (4.30) and (4.31) that

for all  . Letting

. Letting  , we have

, we have  for all

for all  . This proves the uniqueness.

. This proves the uniqueness.

It follows from the inequality (4.30) that we get

for all test functions  . Since

. Since  is given by the uniform limit of the sequence

is given by the uniform limit of the sequence  ,

,  is also continuous on

is also continuous on  . In view of (4.29), it follows from the continuity of

. In view of (4.29), it follows from the continuity of  that for each

that for each

exists. Letting  in (4.29) we have

in (4.29) we have  satisfies quartic functional equation (1.4). Letting

satisfies quartic functional equation (1.4). Letting  we have the inequality

we have the inequality

Now we consider the case  . For this case, replacing

. For this case, replacing  by

by  in (4.23), respectively, and letting

in (4.23), respectively, and letting  and then multiplying the result by

and then multiplying the result by  we have

we have

Using induction argument and triangle inequality we obtain

for all  . Following the similar method in case of

. Following the similar method in case of  , we see that

, we see that

is the unique function satisfying (4.29) so that  exists. Letting

exists. Letting  in (4.37) we get

in (4.37) we get

Now letting  in (4.39) we have the inequality

in (4.39) we have the inequality

This completes the proof.

As an immediate consequence, we have the following corollary.

Corollary 4.4.

Let  be fixed integer with

be fixed integer with  and

and  be a real number. Suppose that

be a real number. Suppose that  in

in  or

or  satisfies the inequality

satisfies the inequality

Then there exists a unique quartic mapping  which satisfies (1.4) and the inequality

which satisfies (1.4) and the inequality

where  .

.

References

Ulam SM: Problems in Modern Mathematics. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY, USA; 1964:xvii+150.

Hyers DH: On the stability of the linear functional equation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1941,27(4):222-224. 10.1073/pnas.27.4.222

Rassias ThM: On the stability of the linear mapping in Banach spaces. Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 1978,72(2):297-300. 10.1090/S0002-9939-1978-0507327-1

Czerwik S: Functional Equations and Inequalities in Several Variables. World Scientific, River Edge, NJ, USA; 2002:x+410.

Faĭziev VA, Rassias ThM, Sahoo PK:The space of (

,

,  )-additive mappings on semigroups. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 2002,354(11):4455-4472. 10.1090/S0002-9947-02-03036-2

)-additive mappings on semigroups. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 2002,354(11):4455-4472. 10.1090/S0002-9947-02-03036-2Hyers DH, Rassias ThM: Approximate homomorphisms. Aequationes Mathematicae 1992,44(2-3):125-153. 10.1007/BF01830975

Hyers DH, Isac G, Rassias ThM: Stability of Functional Equations in Several Variables, Progress in Nonlinear Differential Equations and Their Applications. Volume 34. Birkhäuser, Boston, Mass, USA; 1998:vi+313.

Jung S-M: Hyers-Ulam-Rassias Stability of Functional Equations in Mathematical Analysis. Hadronic Press, Palm Harbor, Fla, USA; 2001:ix+256.

Rassias ThM: On the stability of functional equations and a problem of Ulam. Acta Applicandae Mathematicae 2000,62(1):23-130. 10.1023/A:1006499223572

Rassias JM: Solution of the Ulam stability problem for quartic mappings. Glasnik Matematicki Series III 1999,34(2):243-252.

Chung JK, Sahoo PK: On the general solution of a quartic functional equation. Bulletin of the Korean Mathematical Society 2003,40(4):565-576.

Lee SH, Im SM, Hwang IS: Quartic functional equations. Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications 2005,307(2):387-394. 10.1016/j.jmaa.2004.12.062

Park C-G: On the stability of the orthogonally quartic functional equation. Bulletin of the Iranian Mathematical Society 2005,31(1):63-70.

Găvruţa P: A generalization of the Hyers-Ulam-Rassias stability of approximately additive mappings. Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications 1994,184(3):431-436. 10.1006/jmaa.1994.1211

Aczél J, Dhombres J: Functional Equations in Several Variables, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and Its Applications. Volume 31. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK; 1989:xiv+462.

Borelli C, Forti GL: On a general Hyers-Ulam stability result. International Journal of Mathematics and Mathematical Sciences 1995,18(2):229-236. 10.1155/S0161171295000287

Czerwik S: On the stability of the quadratic mapping in normed spaces. Abhandlungen aus dem Mathematischen Seminar der Universität Hamburg 1992, 62: 59-64. 10.1007/BF02941618

Lee JR, An JS, Park C: On the stability of quadratic functional equations. Abstract and Applied Analysis 2008, 2008:-8.

Skof F: Local properties and approximation of operators. Rendiconti del Seminario Matematico e Fisico di Milano 1983, 53: 113-129. 10.1007/BF02924890

Hörmander L: The Analysis of Linear Partial Differential Operators I: Distribution Theory and Fourier Analysis, Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften. Volume 256. Springer, Berlin, Germany; 1983:ix+391.

Schwartz L: Théorie des Distributions, Publications de l'Institut de Mathématique de l'Université de Strasbourg, No. IX-X. Hermann, Paris, France; 1966:xiii+420.

Chung J, Chung S-Y, Kim D: A characterization for Fourier hyperfunctions. Publications of the Research Institute for Mathematical Sciences 1994,30(2):203-208. 10.2977/prims/1195166129

Chung J, Lee S: Some functional equations in the spaces of generalized functions. Aequationes Mathematicae 2003,65(3):267-279. 10.1007/s00010-003-2657-y

Chung J: Stability of functional equations in the spaces of distributions and hyperfunctions. Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications 2003,286(1):177-186. 10.1016/S0022-247X(03)00468-2

Chung J, Chung S-Y, Kim D: The stability of Cauchy equations in the space of Schwartz distributions. Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications 2004,295(1):107-114. 10.1016/j.jmaa.2004.03.009

Lee Y-S: Stability of a quadratic functional equation in the spaces of generalized functions. Journal of Inequalities and Applications 2008, 2008:-12.

Matsuzawa T: A calculus approach to hyperfunctions. III. Nagoya Mathematical Journal 1990, 118: 133-153.

Kim KW, Chung S-Y, Kim D: Fourier hyperfunctions as the boundary values of smooth solutions of heat equations. Publications of the Research Institute for Mathematical Sciences 1993,29(2):289-300. 10.2977/prims/1195167274

Acknowledgments

The first author was supported by the second stage of the Brain Korea 21 Project, The Development Project of Human Resources in Mathematics, KAIST, in 2009. The second author was supported by the Special Grant of Sogang University in 2005.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, YS., Chung, SY. Stability of Quartic Functional Equations in the Spaces of Generalized Functions. Adv Differ Equ 2009, 838347 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1155/2009/838347

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1155/2009/838347

and

and  such that

such that

as

as  in the sense that for every

in the sense that for every  ,

,

,

,  )-additive mappings on semigroups. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 2002,354(11):4455-4472. 10.1090/S0002-9947-02-03036-2

)-additive mappings on semigroups. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 2002,354(11):4455-4472. 10.1090/S0002-9947-02-03036-2