Abstract

The properties of charmonium states are or will be intensively studied by the B-factories Belle II and BESIII, the LHCb and PANDA experiments and at a future Super-c-\(\tau \) Factory. Precise lattice calculations provide valuable input and several results have been obtained by simulating up, down and strange quarks in the sea. We investigate the impact of a charm quark in the sea on the charmonium spectrum, the renormalization group invariant charm–quark mass \(M_{\mathrm{c}}\) and the scalar charm–quark content of charmonium. The latter is obtained by the direct computation of the mass-derivatives of the charmonium masses. We do this investigation in a model, QCD with two degenerate charm quarks. The absence of light quarks allows us to reach very small lattice spacings down to \(0.023~\hbox {fm}\). By comparing to pure gauge theory we find that charm quarks in the sea affect the hyperfine splitting at a level around 2%. The most significant effects are 5% in \(M_c\) and 3% in the value of the charm quark content of the \(\eta _c\) meson. Given that we simulate two charm quarks these estimates are upper bounds for the contribution of a single charm quark. We show that lattice spacings \(<0.06~\hbox {fm}\) are needed for safe continuum extrapolations of the charmonium spectrum with O(a) improved Wilson quarks. A useful relation for the projection to the desired parity of operators in two-point functions computed with twisted mass fermions is proven.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The charmonium system is frequently characterized as the “hydrogen atom” of meson spectroscopy owing to the fact that it is non-relativistic enough to be reasonably well described by certain potential models [1]. It is a perfect testing ground for a comparison of theory with experiment. Over the last years, there has been a renewed interest in spectral calculations with charmonia because of the experimental discovery of many states which are not predicted by potential models [2], e.g. the so-called X, Y, Z states, like the X(3872) state [3] or the \(P_c\) pentaquark candidates [4]. More exciting experimental data are expected from the B-factories Belle II [5] and BESIII [6], the LHCb experiment [7], the PANDA experiment at FAIR [8] and at a future Super-c-\(\tau \) Factory [9].

Simulations of QCD on the lattice are a first-principle tool for precision computations of charmonium states below the open charm thresholds (\(D\bar{D}\) etc.) [10,11,12,13,14,15], see also [16]. States above the open charm thresholds decay strongly and multi-hadron channels need to be included for a full treatment. The masses of these resonances can be computed in the approximation that they are treated as stable and are accurate up to the hadronic width [10, 11].

For the computation of the charmonium spectrum the relevant quarks to include in the lattice simulations are u, d, s, and c. The question which we address in this work is the necessity to include the charm quark c in the sea, i.e. as a dynamical quark which contributes through loops and not only as a valence quark. QCD with \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=2+1\;(u,d,s)\) dynamical quarks is cheaper to simulate than QCD with \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=2+1+1\;(u,d,s,c)\) dynamical quarks. Adding a dynamical charm quark requires finer lattices than they are needed for the lighter quarks and complicates the tuning of the parameters.

For processes at energies E which are much smaller than the charm–quark mass \(M_{\mathrm{c}}\) the charm quark decouples [17, 18]. It can be integrated out and its effects are absorbed in the renormalization of the gauge coupling and light quark masses, and in small corrections proportional to inverse powers of \(M_{\mathrm{c}}\). In [19,20,21] the decoupling of the charm quark at low energies was studied in a model, namely QCD with \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=2\) degenerate heavy quarks of mass \(1.2\,M_{\mathrm{c}}\gtrsim M \gtrsim M_{\mathrm{c}}/8\). Simulations at very small lattice spacings down to \(a=0.023\,\mathrm{fm}\) in physical volumes comparable to those used in the Yang–Mills theory allow to control the continuum limit. Concerning the renormalization the model study confirmed that treating decoupling in perturbation theory only introduces small non-perturbative corrections which can be estimated through the model calculation. Denoting a low energy scale of mass dimension one by \(\mathcal{S}\), the mass-scaling function defined by

where M is the renormalization group invariant mass of the heavy quark, is universal (i.e. it does not depend on the specific scale chosen) up to non-perturbative \(1/M^2\) corrections \(\Delta \eta ^\mathrm {M}_\mathrm {NP}\). In [21] the conclusion was that \(\Delta \eta ^\mathrm {M}_\mathrm {NP} < 0.014\) for the charm quark in QCD. We emphasize that Eq. (1.1) corresponds to the charm quark content of the nucleon and is needed to compute the cross-section of the scalar interaction of dark matter with nucleons.

In this work we extend the model study of charm loop effects to observables which explicitly depend on a valence charm quark. The paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2 we introduce the model. Section 3 explains our lattice setup based on twisted mass fermions at maximal twist, the observables and the computation of their derivative with respect to the quark mass. In Sect. 4 we present our results for the charm loop effects, specifically in the charmonium spectrum and the renormalized charm–quark mass. We also compute the generalization of the mass-scaling function in Eq. (1.1) to describe the charm–quark mass-dependence of the charmonium states. All our results are evaluated after continuum extrapolation and we discuss the size of lattice artifacts. Section 5 contains the summary of this work. Appendix A shows how to construct two-point functions which project to definite parity states with twisted mass fermions. In Appendix B the charmonium masses obtained on our ensembles are listed.

2 Model

Consider QCD with quarks \(q^i\), \(i=\{u,d,s,c\}\). We denote their Dirac operators by \(D_i\). Our goal is to estimate the contribution of charm–quark loops in physical observables \(A[q^i,U]\), where U represents the gauge field. The expectation value of the observable is

The charm–quark loop effectsFootnote 1 stem from the determinant \(\det D_c\). Quenching the charm, i.e. setting \(\det D_c=1\) means neglecting the charm loops. This approximation is made in the computations of the charmonium spectrum of Refs. [10,11,12,13,14]. In order to assess how good this approximation is, one would need a comparison in the continuum limit with simulations where a dynamical charm quark is added. Assuming this was possible, the comparison would be superfluous since one would stick with the more complete theory anyhow. But adding a dynamical charm quark means a significant increase in the complexity and costs of the simulations. This is so because of the additional tuning of the charm quark mass and the combination of small lattice spacings, which are required by the large charm–quark mass and the large physical volumes, which are needed to accommodate the light mesons. So the really interesting question is if it is possible to decide whether a dynamical charm quark is necessary before doing the simulations.

This is why the study of a model, QCD with just \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=2\) degenerate charm quarks, is appealing. Observables in this model are defined in terms of a doublet of charm quarks \(q^c=(c_1,c_2)\) and their expectation value is

After matching this theory with a Yang–Mills (or pure gauge) theory, the difference in physical observable will be a direct measure of the effects of charm–quark loops. There are two differences with respect to a comparison between QCD with four (u, d, s, and c) and three (u, d, s) quarks: in the model we miss the effects of the light quarks and we double the number of sea charm quarks. Since what we are interested in is a comparison of a theory with and without charm quarks in the sea we do not expect the light quarks to affect the difference of the same quantity computed in the two theories much. The extra charm quark in the sea will make the effects larger. For a low energy quantity, where the theory of decoupling applies, the effects scale proportionally to the number of quarks [21], so they are overestimated by a factor of two in the model. For a quantity with a valence charm quark decoupling does not apply in the obvious wayFootnote 2 and we consider the effects computed with two charm quarks in the sea as an upper bound for those with only one charm quark.

3 Simulations

In this section we introduce the lattice setup used for this work and all the observables under investigation. We mainly focus on quantities with an explicit charm–quark dependence, like charmonium masses, the hyperfine splitting and the renormalization group invariant quark mass.

3.1 Actions and algorithms

We use relatively simple and theoretically well understood lattice actions for our simulations. For the \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=0\) ensembles the standard Wilson plaquette action [22] is employed. In the \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=2\) case, a doublet of twisted mass Wilson fermions is added [23, 24]. In massless schemes, theories with standard and with twisted-mass fermions share the same renormalization factors, as long as other details of the action are the same. We therefore also include a clover term [25] in our action. Although not necessary for O(a) improvement of physical quantities [24] (at maximal twist), it has been shown to reduce \(O(a^2)\) artifacts in some cases [26], and more importantly gives us access to the wide range of renormalization factors that have been determined non-perturbatively in the past. In particular we benefit from the knowledge of the critical mass \(m_{\mathrm{cr}}\) [27, 28] and the axial current and pseudoscalar density renormalization factors \(Z_A\) [29,30,31] and \(Z_P\) [27, 32].

Since one of our goals is a detailed understanding of charm related lattice artifacts, we simulate also at very fine lattice spacings, much finer than what is currently feasible in simulations that include light quarks. Problems related to deficient sampling of topological sectors are avoided by the implementation of open boundary conditions in the time directions [33]. The spatial dimensions are kept periodic.

To summarize, our action is \(S=S_{\mathrm{g}} + S_{\mathrm{f}}\), with gauge action

where the summation is over all oriented plaquettes p on the lattice, weighted by w(p) which is one everywhere except for spatial plaquettes on the temporal boundary time-slices, where it is 1 / 2. U(p) is the product of four SU(3) gauge fields \(U_\mu (x)\) around the elementary plaquette p. Gauge fields are periodic in spatial directions and absent on temporal links sticking out of the lattice (i.e. open boundaries). The free parameter of the gauge action is the bare coupling \(g_0^2 \equiv 6/\beta \). In case of the \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=2\) simulations, a fermionic action is added

where \(\chi = (c_1,c_2)^\top \) is a flavor doublet of quarks and the Dirac operator is

with bare mass \(m_0\) and twisted bare mass \(\mu \). The third Pauli matrix \(\tau ^3\) in the twisted mass term acts in flavor-space, all other terms of the operator are flavor diagonal.

is the massless Wilson operator, containing the usual covariant forward and backward finite difference operators \(\nabla _\mu \chi (x) = U_\mu (x)\chi (x+{\hat{\mu }})-\chi (x)\) and \(\nabla ^*_\mu \chi (x) = \chi (x) - U^\dagger _\mu (x-{\hat{\mu }})\chi (x-{\hat{\mu }})\). Finally, the operator in the Sheikholeslami-Wohlert term acts as

A symmetric discretization of the field strength tensor \({\hat{F}}_{\mu \nu }\), as e.g. in [34], is used. The fermionic fields are periodic in spatial directions and satisfy \(D\chi =0\) on the first and last time-slice of the lattice. The fermionic part of the action has dimensionless simulation parameters \(\kappa \equiv \frac{1}{2am_0+8}, a\mu \) and \(c_{\mathrm{sw}}\). The above choice for the actions corresponds to setting the gluonic and fermionic boundary improvement terms to their tree level values.

Both \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=0\) and \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=2\) theories are simulated with a Hybrid Monte Carlo (HMC) [35] algorithm. The molecular dynamics equations are integrated using a fourth order Omelyan–Mryglod–Folk integrator. In the case with fermions a multi-level variant is employed, with fermionic forces being integrated with a coarser step size than the forces deriving from the gauge action. In addition the quark determinant is factorized into two factors which are then represented by two separate path integrals over pseudo fermion fields [36].

The costs are dominated by solutions of the Dirac equation. The relatively high quark masses in our simulations, mean that a standard conjugate gradient algorithm is often more efficient than more complicated preconditioned variants. On the finer lattices however, SAP preconditioning [37] of the equations involving the light Hasenbusch mass is beneficial. Our simulations are carried out using a variant of openQCD [38]. A minor change allows us to choose a different twisted mass parameter in the SAP preconditioner than in the simulation [21, 39]. Table 1 summarizes our simulation parameters.

The simulation algorithm performs very well. In particular no increased critical slowing down due to deficient sampling of topological sectors can be observed. The scaling of the exponential auto-correlation time with the lattice spacing is compatible with the expected \(\tau _{\mathrm{exp}} \propto a^{-2}\) behavior [33]. The expected scaling of autocorrelation times with open boundary conditions has been shown in Fig. 8 of Ref. [21].

3.2 Observables

3.2.1 \(t_0\)

The Wilson-flow equation [40, 41]

relates a “smeared” gauge field \(V_\mu (x,t)\) at flow time t to the original gauge field \(U_\mu (x)\), that is integrated over in the path integral. \(S_{\mathrm{g}}[V]\) is a gauge action of the smeared fields, in our case the Wilson plaquette action, and the link differential operator \(\partial _{x,\mu }\) is defined in the usual way [40, 42]. It has been shown that correlators constructed from gauge fields at \(t>0\) are automatically renormalized [43]. Among other things, this allows to define the low-energy length scale \(t_0\) [40] as the flow time t at which

In this equation E(t) denotes the Yang-Mills action density at flow-time t, away from the temporal boundaries. A different discretization than the one used in the simulations may be used. We follow [34] and use a symmetrized clover definition

where \(G_{\mu \nu }^a(x,t)\) are the Lie algebra components of the lattice field strength tensor.

3.2.2 Isovector meson masses

We study mesons that are ground states in the channels that are excited by operators \({\bar{\psi }} \Gamma \tau ^a \psi \). Twisted mass fermions at maximal twist, \({\bar{\chi }}\) and \(\chi \), are related to the fields in the physical basis by

This means that some operators take an unusual form. For flavor components \(\tau ^1\) and \(\tau ^{2}\), the relations are summarized in Table 2.

Meson masses can be extracted from zero momentum correlation functions of the form

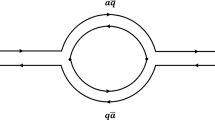

with various choices of the operators \(\mathcal {O}_i\). We work with definite flavor assignments, e.g. \(P^+ \equiv P^1 +iP^2 = {\bar{c}}_1 \gamma _5 c_2\). Then, integrating over the fermions leaves us with a single connected diagram of the form \(-\sum _{\mathbf {x},\mathbf {y}} \langle \mathrm{tr}[ \Gamma _1 {{\mathcal {S}}}_1(x,y) \Gamma _2 {{\mathcal {S}}}_2(y,x)]\rangle ^\mathrm{gauge}\), where \(\Gamma _i\) are \(4\times 4\) matrices related to the operators in the correlation function, and \({{\mathcal {S}}}_1\) (\({{\mathcal {S}}}_2\)) is the inverse Dirac operator with positive (negative) twisted mass term. Spatial translation invariance could be exploited to eliminate one of the sums, which would allow to compute a correlator at the cost of 12 solutions of the Dirac equation per choice of \(y_0\). The signal however is highly improved, by keeping the two sums. The trace can then be efficiently estimated stochastically. We use time-dilution with 16 U(1) noise sources per time-slice, which amounts to 16 inversions per \(y_0\) value and Dirac structure.

An improved signal and exact symmetries are achieved by defining the averages

Enforcing the continuum time reflection symmetries prevents opposite parity operators from mixing, as explained in Appendix A. From the exponential decay of these correlators at \(x_0 \gg a \), meson masses are extracted. First, effective masses are computed

and the meson mass is then given as a weighted plateau average

The start of the plateau, \(t_{\mathrm{low}}\), is chosen such that excited state contributions are completely negligible, and the weights w are given by the inverse squared errors of the corresponding effective masses. All masses that we extract are those of iso-vector mesons. In the light sector these would be called pions or kaons (\({\bar{f}}_{PP}\)), \(\rho \)- or \(K^*\)-mesons (\({\bar{f}}_{VV}\)), \(a_0\), \(f_0\), \(K_0^{\star }\) (\({\bar{f}}_{SS}\)), \(h_1\), \(b_1\) (\({\bar{f}}_{TT}\)). However, since both our quarks have the mass of a charm–quark, the meson masses that we obtain are more comparable to the charmonia masses \(\eta _c\), \(J/\psi \),\(\ldots \) respectively. The difference being, that these are iso-scalars and the determination of their masses would require the computation of disconnected (charm annihilation) diagrams.

3.2.3 PCAC mass

Partial conservation of the axial current is an operator relation

On the lattice it holds up to lattice artifacts, when inserted into any correlation function, as long as A and P are at a different positions than all other operators in the correlator. These lattice artifacts depend on the exact choice of correlation function, and can be quite large. We extract the bare PCAC quark mass from

where \({\tilde{\partial }}_\mu \) denotes the symmetric finite difference operator. The lattice artifacts in this quantity increase, when the correlators are evaluated close to the boundary (small \(x_0\)). We form an average value from the time-slices in the plateau region away from boundaries.

For us the main use of the PCAC mass is to find the critical value of the bare mass \(m_0\), i.e. the maximal twist condition. It is given by the value at which \(m_{\mathrm{PCAC}}=0\). Instead of determining it ourselves, we use very precise critical masses obtained in [27, 28]. These were computed from slightly different correlation functions in a finite volume, and differ from ours by an O(a) lattice artifact. We thus do not expect the PCAC masses that we determine to be zero, but to be small and to vanish when the continuum limit is approached. By computing them, we put this expectation to a test. Figure 1 demonstrates that indeed, up to lattice artifacts, we are at maximal twist. If we consider the usual definition of the twist angle

the largest deviation from maximal twist (\(\omega =\pi /2\)) that we encounter in our simulations is around \(6\%\) in the ensemble E, whilst the smallest deviation is around \(2\%\) in the ensemble W.

3.2.4 RGI quark mass

At maximal twist a renormalized quark mass is given by \({\overline{m}} = Z_P^{-1} \mu \), and depends on the scale and scheme in which \(Z_P\) was computed. Away from maximal the more general relation

holds. We neglect the (very small) contribution due to non-vanishing \(m_{\mathrm{PCAC}}\) in our determination, after verifying that it is compatible with being of O(a). The axial current renormalization factor \(Z_A\) is scale independent. It has been determined non-perturbatively in the \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=0\) theory with our action, by exploiting current algebra relations in a massless Schrödinger functional [29]. The same technique has also been applied to the \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=2\) theory [30]. In this case also a more precise determination based on universal relations between correlators in a chirally rotated Schrödinger functional exists [31], and these are the values that we use here. The pseudoscalar renormalization factor \(Z_P\) depends on the renormalization scheme and scale. It is known non-perturbatively in the SF scheme in both \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=0\) [32] and \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=2\) [27] theories for a wide range of bare couplings, albeit at slightly different scales. The renormalized charm quark mass can thus be computed in the continuum limit, in this particular scheme. To be able to compare the two theories, also the scales should match. We go one step further and compute directly the RGI masses, which are scale and scheme independent. The necessary relations between renormalized and RGI masses are well known for the scales and schemes used above, namely \(M/ {\overline{m}} = 1.157(12)\) in the \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=0\) theory [32], and \(M/{\overline{m}} = 1.308(16)\) in the theory with two dynamical quarks [27].

3.2.5 Twisted mass derivatives

We also computed the derivatives of all the observables above, with respect to the twisted mass parameter \(\mu \). The twisted mass derivative of a primary observable A is given by

Most quantities we are interested in, are non-linear functions of various primary observables (e.g. \(m_P\), which depends on the correlator \({\bar{f}}_{PP}\) at various distances in the plateau region). For these the chain rule dictates

None of the observables that we consider have an explicit \(\mu \) dependence, so the last term in Eq. (3.23) is absent. The derivative of the action is \(\mathrm{d}S/\mathrm{d}\mu = \sum _x {\bar{\chi }} i\gamma _5\tau ^3\chi \), and this is all that is needed to compute the twisted-mass derivatives of purely gluonic observables. More precisely,

The last line is a consequence of the twisted-mass relation \(D_1 - D_2 = 2i\gamma _5 \mu \) and allows for a more precise stochastic determination of the trace [44]. We found that 64 U(1) noise vectors are enough for the errors in the determination of the derivative to be dominated by gauge-noise, rather than the noise from the stochastic trace evaluation.

If the observables depend on fermionic fields too, the first term of Eq. (3.23) gives rise to new contractions that have to be computed. These are different for every fermionic observable. In the case of our two-point functions Eq. (3.11) we find contractions of the form \(-a^{10}\sum _{\mathbf {x},\mathbf {y},z} \langle \mathrm{tr}[ \Gamma _1 {{\mathcal {S}}}_{2}(x,y) \Gamma _2 {{\mathcal {S}}}_1(y,x)] \mathrm{tr}[\gamma _5({{\mathcal {S}}}_1(z,z)-{{\mathcal {S}}}_2(z,z))]\rangle ^{\mathrm{gauge}}\), that can be immediately computed because both traces have already been estimated for the evaluation of the correlator and of \(\mathrm{d}S/\mathrm{d}\mu \) respectively, and new terms

that require some attention. When evaluated stochastically together with the correlator itself, the number of necessary inversions is increased by a factor of 3. While the \(\mathrm{d}S/\mathrm{d}\mu \) terms quantify the dependence on the sea-quarks, this last term gives the valance quark mass dependence of the correlator, which is generally much stronger – especially with heavy quarks.

3.2.6 Mass scaling functions

At last, we also investigate the mass scaling functions

where \(m_x\) denotes the mass of a meson in a generic x channel (scalar, pseudoscalar, vector, axial vector, tensor) and M is the renormalization group invariant quark mass. Note that \(\eta _x\) is a renormalized quantity and its continuum limit can be easily extracted from the measurements performed at different lattice spacings, without the need of any renormalization factor. Notice that by the Hellman-Feynman-Theorem [45], \(\eta _x\) is proportional to the scalar charm quark density between meson states x, i.e. the \(\sigma \)-term

Once the twisted mass derivatives of the meson correlators are known, the determination of \(\eta _x\) amounts to the evaluation of Eq. (3.24) with a particular function f. Since the action of \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=0\) QCD does not depend on \(\mu \), the calculation is greatly simplified in this case. Eq. (3.23) receives a single contribution of the form \(\langle \mathrm{d}{\tilde{A}}[D^{-1},U]/\mathrm{d}\mu \rangle \). In the \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=2\) theory on the other hand, also the \(\mu \)-derivative of the action must be taken into account.

3.3 Parameters, tuning and mis-tuning corrections

Apart from the lattice size, the bare parameters of the \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=2\) simulations are the inverse bare coupling \(\beta \), the bare mass \(am_0\) and the bare twisted mass \(a\mu \). The choice of \(\beta \) corresponds to a choice of the lattice spacing. We choose to simulate at \(\beta \in \{5.3, 5.5, 5.6, 5.7, 5.88, 6.0\}\) which spans a wide range of lattice spacings, see Table 5 and allows for very controlled continuum extrapolations.

The bare mass is set to its critical value \(m_0=m_{\mathrm{cr}}\). To achieve this, the values in [27] are fitted to a Padé function, as described in [21]. This puts us to maximal twist, up to \(O(a^2)\). In this situation the physical quark mass is given by the twisted mass parameter \({\overline{m}} = Z_P^{-1} \mu \). On our finest lattice at \(\beta =6.0\) we choose

where the ratio of the RGI charm quark mass and the two flavor \(\Lambda \) parameter is set to 4.87, the pseudoscalar renormalization factor at scale \(L_1^{-1}\) and \(\beta =6.0\) in the SF scheme is \(Z_P=0.5184\,\,(33)\) [27], the relation between a renormalized quark mass in the SF-scheme at scale \(L_1^{-1}\) and the RGI quark mass M is known in the continuum \(M/\overline{m}(L_1^{-1}) =1.308\,\,(16) \) [27], and \(\Lambda _{\overline{\mathrm{MS}}}L_1 = 0.649 \,\,(45)\) [46]. Finally \(L_1\) in lattice units is obtained by an interpolation of \(L_1/a\) vs \(\beta \) data from [27] to \(\beta =6.0\). A quadratic fit of \(\mathrm{log}(L_1/a)\) as a function of \(\beta \), describes the data very well and yields \(L_1/a_{\beta =6.0} = 17.27\,\,(70)\). The quite substantial errors mean, that our simulated mass corresponds to the charm quark mass only up to about \(10\%\). This is however fully sufficient for us, as long as the relative mass differences between the different ensembles are under better control. To achieve this, we do not use Eq. (3.31) at the other lattice spacings. Instead we proceed as follows: the dimensionless, renormalized quantity

is determined on the ensemble with the finest lattice spacing. On the coarser lattices \(a\mu \) is tuned such that the same value of \(\sqrt{t_0} m_P\) is obtained. This condition determines the bare twisted mass parameter very precisely and ensures that all ensembles have the same renormalized quark mass up to \(O(a^2)\). Finally, the clover coefficient \(c_{\mathrm{sw}}\) is set to its non-perturbatively determined value [47].

The tuning of the twisted mass parameter can be only carried out to a limited precision - at most to within the statistical errors. To account for the mis-tuning, a correction is applied to all observables, based on the computed twisted mass derivatives. First a target tuning point \(\mu ^\star \) is determined

and afterwards all quantities, denoted by \(\Phi \) below, are corrected

The error of the tuning point \(\mu ^*\) is propagated to the value of \(\Phi (\mu ^*)\) taking all correlations into account. It is assumed that the initial tuning was precise enough for the omitted quadratic terms to be negligible, compared to the statistical precision. Figure 2 demonstrates the procedure.

The solid square and circular markers are direct simulation results for \(t_0/a^2\) (top) and \(am_V\) (bottom) on our coarsest ensembles with \(\beta =5.3\). The simulations were carried out at slightly different masses, namely \(a\mu =0.36151\) (circle) and \(a\mu =0.30651\) (square). The lines, with their respective error bands illustrate the value and error of the derivative of the observable with respect to the twisted mass parameter. The pentagram depicts the values obtained at the tuning point Eq. (3.32) . Its vertical error bar is the complete error, including all correlations

A comparison with direct simulations indicates that even for large shifts of \(\approx 15\%\) in \(a\mu \) the linear approximation works well. The true shifts, that are needed are all much smaller, at most \(5.40 \%\). Note that the \(\mu \)-shifts could also be computed using the mass reweighting, as explained in [48, 49].

The \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=0\) simulations are carried out at \(\beta \in \{6.1,6.34,6.672,6.9 \}\). The valence quarks have \(m_0=m_{\mathrm{cr}}\) [50], non-perturbative \(c_{\mathrm{sw}}\) from [50] and three values of the twisted mass parameter, chosen such that a short interpolation to the value of \(\sqrt{t_0}m_P\) given in Eq. (3.32) can be performed. An example of this procedure is shown in Fig. 3. Since decoupling applies to \(t_0\), the condition Eq. (3.32) means that the quark mass in the \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=0\) theory is the same as in the theory with two flavors, up to \(O(a^2)\) and tiny \(O(\Lambda ^2/M_c^2)\) power corrections [20, 21].

Interpolation of the measured pseudoscalar masses (circles) on the \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=0\) ensemble qW (see Table 1). The horizontal line depicts the tuning point Eq. (3.32). The vertical lines are the resulting interpolated twisted mass parameter \(a\mu ^{\star }\) and its statistical error. The measured vector, scalar and tensor mesons masses (diamonds, triangles and squares respectively) can then be interpolated to the tuning point, resulting in the corresponding solid markers. In their error bars all the correlations among the data have been taken into account

3.4 Data analysis

We use the \(\Gamma \)-method [51] for the determination of statistical uncertainties. Observables like the effective mass Eq. (3.17) are non-linear functions of “primary observables”, and their errors are determined as described in [52]. When incorporating the mis-tuning corrections of Sect. 3.3 the necessary nonlinear functions can become quite unwieldy. For instance, the vector meson mass at \(\mu ^\star \) depends on the vector correlator in the plateau region, but also on the pseudoscalar correlator in its plateau region, to determine how big a shift in \(\mu \) is required. Furthermore, the vector mass depends on the \(\mu \)-derivatives of these correlators, on the \(\mu \)-derivative of the action and on the \(\mu \)-derivative of the action times the correlators. Combinations like \(\sqrt{t_0}m_V\) depend on even more primary data.

4 Results

4.1 Raw results

We measured all observables described in the previous section on all ensembles, except of \(m_T\) and \(m_S\) which were measured only on a subset and the mass derivatives, which were not measured on the W ensemble. A somewhat delicate issue is the proper choice of the plateau regions over which the effective masses are averaged. The leading correction to a constant effective mass is given by

where \(\Delta _1\) (\(\Delta _2\)) is the distance between m and the first (second) excited state. In a first preliminary fit we determine \(\Delta _1\) and c. We are then in the position to choose the plateau region such, that the influence of the excited states on the plateau average Eq. (3.18) is negligible compared to its statistical uncertainty. The thus determined plateau regions are collected in Table 3. Figure 4 demonstrates the procedure for the case of ensemble W. The effective masses in the axial-vector channel become too noisy, before a clean plateau is reached and are hence excluded from the tables.

The results for the plateau averages are summarized in Table 6 in Appendix B, which shows the results at the simulated parameters, as well as the values corrected for small mis-tunings in the twisted mass parameter.

The effective masses on the W ensemble for the pseudoscalar (circles), vector (diamonds), scalar (triangles) and tensor (squares) channels are displayed, together with the plateau average and its error band. The fit to the leading correction Eq. (4.1) is also shown

4.2 Continuum extrapolations

We perform continuum extrapolations of dimensionless quantities. These are either ratios of meson masses, namely \(m_V/m_P\), \(m_S/m_P\) and \(m_T/m_P\), or the mass-scaling functions \(\eta _P\) and \(\eta _V\). One last quantity is the renormalized quark mass. We take the continuum limit of the dimensionless ratio of \({\overline{m}}\) and \(m_P\). All fits are restricted to a region where the data can be well described by the expected leading scaling violations of order \(a^2\). This means, neglecting data with lattice spacings coarser than \(a^2/t_0 > 0.25\).

Figures 5, 6 and 7 and Table 4 summarize our findings. The data entering the fits are collected in Table 7.

The results in the continuum limit are collected in Table 4.

4.3 Dynamical charm effects

The comparison of continuum results in the \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=2\) theory with those in the \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=0\) theory directly quantifies the typical size of the effects, that the inclusion of dynamical charm quarks have on observables with valence charm quarks.

Although they were determined very precisely, no significant effect can be seen in the meson mass spectrum. The most significant deviations of around \(1.6\sigma \) are found in the ratios \(m_V/m_P\) and \(m_S/m_P\). The relative differences between the central values of the first ratio are only \(([m_V/m_P]^{{N_{\mathrm{f}}}=2} - [m_V/m_P]^{{N_{\mathrm{f}}}=0})/[m_V/m_P]^{{N_{\mathrm{f}}}=2} = 0.12\,\,(7)\)%. For the hyperfine splitting \((m_V-m_P)/m_P\) this means a charm quark effect of around 2%. In the \(m_S/m_P\) ratio the central values deviate by \(2.7\,\,(1.6)\%\).

A clearer difference between the \(N_f=0\) and \(N_f=2\) theories can be observed in the mass-scaling functions and in the RGI quark mass. The values of \(\eta _P\) and the quark mass differ by almost \(3\sigma \). The relative differences are \((\eta _P^{{N_{\mathrm{f}}}=2}-\eta _P^{{N_{\mathrm{f}}}=0})/\eta _P^{{N_{\mathrm{f}}}=2} = 3.4\,\,(1.1) \%\) and \(([M_c/m_P]^{{N_{\mathrm{f}}}=2}-[M_c/m_P]^{{N_{\mathrm{f}}}=0})/[M_c/m_P]^{{N_{\mathrm{f}}}=2} = 5.0\,\,(1.8)\%\). An even larger (but less significant) difference is found in \(\eta _V\).

4.4 Lattice artifacts

Having access to very fine lattice spacings is crucial for reliable continuum extrapolations. Although our fermionic action, i.e. twisted mass fermions with an additional clover term, is known to have relatively mild lattice artifacts, the continuum value of e.g. \(m_V/m_P\) would be significantly underestimated if we had access only to our two coarsest lattices (E and N). The finer of the two has a lattice spacing of \(a\approx 0.049\) fm, which is comparable to the finest lattice spacings typically achievable in large-volume simulations with light quarks. The situation is depicted in Fig. 8.

The presence of large lattice artifacts of \(O( (a\mu )^2 )\) not only affects observables like \(m_V/m_P\), but also the value of the lattice spacing a itself. Since it is obtained by determining some hadronic length scale \(L^{\mathrm{had}}/a\) in lattice units at finite lattice spacing and dividing it by the continuum value in fm, i.e. \(a = a/L^{\mathrm{had}} \times L^{\mathrm{had, cont}}\), its value depends on the lattice artifacts present in \(L^{\mathrm{had}}\). In our case one possibility to compute the lattice spacings is through the scale \(L^{\mathrm{had, cont, 1}} \equiv L_1 = 0.40\,\,(1)\) fm. Its values in lattice units are known for our bare couplings and the resulting lattice spacings are between \(a^{L_1} = 0.023\) fm on ensemble W and \(a^{L_1} = 0.066\) fm on ensemble E. Alternatively, one could determine the lattice spacing through \(L^{\mathrm{had, cont, 2}} \equiv \sqrt{t_0(M)} = 0.1131\,\,(38)\) fm [21]. While the two lattice spacing determinations agree well on the fine ensembles, the difference is quite substantial on the coarsest one, where we find \(a^{t_0} \approx 0.1\) fm, i.e. we observe a 37% lattice artifact in a! Since \(t_0/a^2\) is also determined on the quenched ensembles, we can determine their lattice spacings using the decoupling relation \(\sqrt{t_0(M)}^{{N_{\mathrm{f}}}=2} = \sqrt{t_0}^{{N_{\mathrm{f}}}=0} + O(M^{-2})\). Note that lattice spacings determined by using the \(N_f=0\) theory as an effective theory for our massive two flavor theory differ from those determined by using it as an (uncontrolled) approximation to full QCD. In particular these lattice spacings depend on the value of M in the fundamental theory. This is also the reason why our value of \(M_c\) does not agree with other quenched determinations, like e.g. [53]. Table 5 summarizes our scale setting.

5 Conclusions

In this work we presented a determination of the effects of charm quarks in the sea based on a simulation of a model, QCD with \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=2\) charm quarks. By comparing to the \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=0\) pure gauge theory at the matching point defined in Eq. (3.32) we can compute the size of these effects. We find that they are below 2% for the hyperfine splitting of charmonium. These are good news for lattice QCD computations of charmonium based on simulations of \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=2+1\) light quarks in the sea. We also demonstrate in Fig. 8 that lattice spacings \(a<0.06~\)fm are needed for safe continuum extrapolations of the charmonium spectrum when using O(a) improved Wilson quarks.

We also computed the effects of sea charm quarks in the mass-scaling function \(\eta \) of the charmonium masses Eq. (3.29) and in the renormalization group invariant charm–quark mass \(M_{\mathrm{c}}\). Table 4 lists the comparison in the continuum limit of these quantities in the \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=2\) and \({N_{\mathrm{f}}}=0\) theory. The effects of the charm sea quarks are clearly resolved and their size is 3% for \(\eta _P\) and 5% for \(M_{\mathrm{c}}\). We notice that our results are upper bounds for the effects of a charm sea quark in QCD since in our model we have doubled their number.

Further analysis to compute charm loop effects in decay constants and finestructure of \(B_c\) mesons is in progress. So far the disconnected contributions due to charm annihilation [54] have been neglected since we computed isovector charmonium masses in our model. Work on these contributions is under way.

Notes

Notice that here we mean non-perturbative effects due to quark loops on arbitrary gauge backgrounds.

Decoupling might apply for differences of masses or for binding energies.

References

E. Eichten, K. Gottfried, T. Kinoshita, J.B. Kogut, K.D. Lane, T.-M. Yan, Phys. Rev. Lett. 34, 369–372 (1975) (Erratum: Phys. Rev. Lett. 36, 1276(1976))

S.L. Olsen, XYZ Meson Spectroscopy. in Proceedings, 53rd International Winter Meeting on Nuclear Physics (Bormio 2015) (Bormio, Italy, 2015) January 26–30, 2015

S.K. Choi et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 262001 (2003)

R. Aaij et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 072001 (2015)

W. Altmannshofer, et. al., The Belle II Physics Book (2018)

M. Ablikim et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 118(9), 092002 (2017)

R. Aaij et al., Physics case for an LHCb Upgrade II – opportunities in flavour physics, and beyond, in the HL-LHC era (2018)

G. Barucca et al., Eur. Phys. J. A 55(3), 42 (2019)

S. Eidelman, Nucl. Part. Phys. Proc. 260, 238–241 (2015)

L. Liu, G. Moir, M. Peardon, S.M. Ryan, C.E. Thomas, P. Vilaseca, J.J. Dudek, R.G. Edwards, B. Joo, D.G. Richards, JHEP 07, 126 (2012)

G.K.C. Cheung, C. O’Hara, G. Moir, M. Peardon, S.M. Ryan, C.E. Thomas, D. Tims, JHEP 12, 089 (2016)

E. Follana, Q. Mason, C. Davies, K. Hornbostel, G.P. Lepage, J. Shigemitsu, H. Trottier, K. Wong, Phys. Rev. D 75, 054502 (2007)

C. DeTar, A.S. Kronfeld, S.-H. Lee, D. Mohler, J.N. Simone, Phys. Rev. D 99(3), 034509 (2019)

M. Padmanath, S. Collins, D. Mohler, S. Piemonte, S. Prelovsek, A. Schäfer, S. Weishaeupl, Phys. Rev. D 99(1), 014513 (2019)

M. Kalinowski, M. Wagner, Phys. Rev. D 92(9), 094508 (2015)

F. Knechtli, EPJ Web Conf. 202, 01006 (2019)

T. Appelquist, J. Carazzone, Phys. Rev. D 11, 2856 (1975)

S. Weinberg, Phys. Lett. B 91, 51–55 (1980)

M. Bruno, J. Finkenrath, F. Knechtli, B. Leder, R. Sommer, Phys. Rev. Lett. 114(10), 102001 (2015)

F. Knechtli, T. Korzec, B. Leder, G. Moir, Phys. Lett. B 774, 649–655 (2017)

A. Athenodorou, J. Finkenrath, F. Knechtli, T. Korzec, B. Leder, M.K. Marinković, R. Sommer, Nucl. Phys. B 943, 114612 (2019)

K.G. Wilson, Phys. Rev. D10, 2445–2459 (1974) (319(1974))

R. Frezzotti, P.A. Grassi, S. Sint, P. Weisz, JHEP 08, 058 (2001)

R. Frezzotti, G.C. Rossi, JHEP 08, 007 (2004)

B. Sheikholeslami, R. Wohlert, Nucl. Phys. B 259, 572 (1985)

P. Dimopoulos, H. Simma, A. Vladikas, JHEP 07, 007 (2009)

P. Fritzsch, F. Knechtli, B. Leder, M. Marinkovic, S. Schaefer, R. Sommer, F. Virotta, Nucl. Phys. B 865, 397–429 (2012)

P. Fritzsch, N. Garron, J. Heitger, JHEP 01, 093 (2016)

M. Lüscher, S. Sint, R. Sommer, H. Wittig, Nucl. Phys. B 491, 344–364 (1997)

M. Della Morte, R. Hoffmann, F. Knechtli, R. Sommer, U. Wolff JHEP 07, 007 (2005)

M. Dalla Brida, T. Korzec, S. Sint, P. Vilaseca, Eur. Phys. J. C 79(1), 23 (2019)

A. Jüttner, Precision lattice computations in the heavy quark sector. PhD thesis, Humboldt U., Berlin (2004)

M. Lüscher, S. Schaefer, JHEP 07, 036 (2011)

M. Lüscher, Advanced lattice QCD, in Probing the standard model of particle interactions. Proceedings, Summer School in Theoretical Physics, NATO Advanced Study Institute, 68th session, July 28–September 5, 1997. Pt. 1, 2 (Les Houches, France, 1998), pp. 229–280

S. Duane, A.D. Kennedy, B.J. Pendleton, D. Roweth, Phys. Lett. B 195, 216–222 (1987)

M. Hasenbusch, Phys. Lett. B 519, 177–182 (2001)

M. Lüscher, Comput. Phys. Commun. 156, 209–220 (2004)

M. Lüscher, S. Schaefer, Comput. Phys. Commun. 184, 519–528 (2013)

C. Alexandrou, S. Bacchio, J. Finkenrath, A. Frommer, K. Kahl, M. Rottmann, Phys. Rev. D 94(11), 114509 (2016)

M. Lüscher, JHEP 08, 071 (2010) (Erratum: JHEP03, 092(2014))

R. Narayanan, H. Neuberger, JHEP 03, 064 (2006)

M. Lüscher, Commun. Math. Phys. 293, 899–919 (2010)

M. Lüscher, P. Weisz, JHEP 02, 051 (2011)

K. Jansen, C. Michael, C. Urbach, Eur. Phys. J. C 58, 261–269 (2008)

R.P. Feynman, Phys. Rev. 56, 340–343 (1939)

M. Della Morte, R. Frezzotti, J. Heitger, J. Rolf, R. Sommer, U. Wolff, Nucl. Phys. B 713, 378–406 (2005)

K. Jansen, R. Sommer, Nucl. Phys. B530, 185–203 (1998) (Erratum: Nucl. Phys. B643, 517(2002))

J. Finkenrath, F. Knechtli, B. Leder, Nucl. Phys. B877, 441–456 (2013) (Erratum: Nucl. Phys. B880, 574(2014))

B. Leder, J. Finkenrath, PoS LATTICE2014, 040 (2015)

M. Lüscher, S. Sint, R. Sommer, P. Weisz, U. Wolff, Nucl. Phys. B 491, 323–343 (1997)

U. Wolff, Comput. Phys. Commun. 156, 143–153 (2004) (Erratum: Comput. Phys. Commun. 176, 383 (2007))

S. Schaefer, R. Sommer, F. Virotta, Nucl. Phys. B 845, 93–119 (2011)

J. Rolf, S. Sint, JHEP 12, 007 (2002)

L. Levkova, C. DeTar, Phys. Rev. D 83, 074504 (2011)

Acknowledgements

We thank our colleagues in the ALPHA collaboration for access to data analysis tools. We gratefully acknowledge the computer resources granted by the John von Neumann Institute for Computing (NIC) and provided on the supercomputer JUROPA at Jülich Supercomputing Centre (JSC) and by the Gauss Centre for Supercomputing (GCS) through the NIC on the GCS share of the supercomputer JUQUEEN at JSC, with funding by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and the German State Ministries for Research of Baden-Württemberg (MWK), Bayern (StMWFK) and Nordrhein-Westfalen (MIWF). S.C. acknowledges support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant agreement No. 642069.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A: Parity and time-reflection symmetries

Following transformations can be considered as a change of variables in the lattice path integral:

Parity

Time reflection

They are symmetries of the twisted mass action only if \(\mu =0\). In general these transformations lead to relations between expectation values in theories with positive and with negative twisted masses. E.g. for the two-point functions like Eq. (3.11) one finds

With standard Wilson fermions (\(\mu =0\)), these equations can be used to show that \(\langle \mathcal {O}_1 \mathcal {O}_2\rangle = 0\) if the operators \(\mathcal {O}_1\) and \(\mathcal {O}_2\) have opposite parity, i.e. if \(\mathcal {P}[\mathcal {O}_1]\mathcal {P}[\mathcal {O}_2] = -\mathcal {O}_1 \mathcal {O}_2\). As a consequence, an operator with a definite parity will only excite states with the same parity. This property is lost in the twisted mass formulation, and in general operators will excite states with both parities.

The combined \({\mathcal {TP}}\) transformation is a symmetry of the twisted mass action

For the averaged correlators Eqs. (3.12)–(3.16) this means

It is now easy to see that the averaged correlator vanishes, if \(\mathcal {P}[\mathcal {O}_1]\mathcal {P}[\mathcal {O}_2] = -\mathcal {O}_1 \mathcal {O}_2\). So, by enforcing the continuum time reflection symmetry of the correlator, automatically the mixing of opposite parity operators is prohibited.

Appendix B: Tables

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Funded by SCOAP3

About this article

Cite this article

Calì, S., Knechtli, F. & Korzec, T. How much do charm sea quarks affect the charmonium spectrum?. Eur. Phys. J. C 79, 607 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-019-7108-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-019-7108-6