Abstract

We investigate the effect of electric charge in anisotropic compact stars with conformal symmetry. We assume that the pressure and the density of the matter inside the stellar structure are large with strong gravitational fields. The strong electric field produces significant effects on the phenomenology of the stellar objects, in order of \( 10^{20}~\text {V m}^{-1}\) in MKSA units. The conformal symmetry condition produces an integral relationship between the metric functions. We use this condition to find a new anisotropic solution to the Einstein–Maxwell field equations. This solution is relevant in modelling a relativistic compact star. Radii and masses are consistent with stellar objects such PSR J1614-2230, Vela X1, PSR J1903+327 and Cen X-3. The mass-radius ratio and the surface red shift are in agreement with realistic constraints. Also our model displays constraint on the maximum stellar mass, central density and radius for the upper bound redshift requirements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Spherically symmetric exact solutions in general relativity are important tools in describing the structure and physical properties of stellar compact objects. Charged, self-gravitating anisotropic fluid spheres have been investigated in general relativity since the early work of Bonnor [1]. The theoretical investigations of Ruderman [2] and Canuto [3] on realistic stellar solutions pointed out that the stellar objects may have high density ranges (\(>10^{15}~\text {g cm}^{-3}\)), when the nuclear matter has anisotropic features. As a result anisotropy fluid spheres were studied to describe compact star models. For more details, see Bowers and Liang [4], Herrera and Ponce de Leon [5], Gokhroo and Mehra et al. [6], Herrera and Santos [7], Mak and Harko [8], Hernandez and Nunez [9], Thomas et al. [10], Maurya et al. [11], Maurya et al. [12], Singh and Pant [13] and Ratanpal et al. [14]. Yet at the same time, gravitational collapse is one of the most extreme phenomena in the universe. When there is insufficient pressure to balance the gravitational attraction inside a stellar object, it undergoes sudden gravitational collapse and its physical characteristics change drastically. These facts lead people to believe that the presence of charge in compact objects may prevent gravitational attraction which can counterbalanced by the repulsive Colombian force in addition to the pressure gradient as pointed by Dayanandan et al. [15]. In recent years, there have been several studies of compact star models in the presence of an electric field with Einstein–Maxwell system of equations. The presence of charge may affect values of redshift, radius and maximum mass in stars. The nonlinearity of the Einstein field equations makes them extremely hard to solve analytically. The difficulties in solving the Einstein–Maxwell equations analytically can be alleviated with the presence of a conformal Killing vector placing constraints on the gravitational field, and this simplifies the integration process. Therefore a conformal symmetry is useful in modelling dense relativistic stellar objects. The first models on conformally invariant gravitating spheres were found [16,17,18,19]. Many of these solutions were not regular at the centre. The first regular models of conformally invariant spheres with an anisotropic energy momentum tensor were found by Maartens and Maharaj [20].

Conformal symmetries have been widely studied in static spherical spacetimes by Maartens et al. [21, 22] and Tupper et al. [23]. Manjonjo et al. [24] utilised the component of the Weyl tensor to generate conformally flat and nonconformally flat static metrics with conformal symmetries. In a later result Manjonjo et al. [25] proved that a conformal vector yields an explicit connection relating the metric functions in general; isotropic and anisotropic pressures can then produce models with conformal symmetry. These studies can be utilised to model compact stars in relativistic astrophysics. Mak and Harko [26] modelled quark stars with conformal motions in general relativity. Relativistic compact objects a linear equation of state were studied by Esculpi and Aloma [27]. Rahaman et al. [28] and Shee et al. [29] investigated anisotropic bodies with a nonstatic conformal symmetry, anisotropy and an assumed specified spacetime potential. Quintessence fields [30], gravastar models [31] and braneworld structures [32] were studied as stellar models with a conformal symmetry. These investigations indicate that the existence of a conformal symmetry in the manifold is a valuable approach in producing exact solutions of Einstein–Maxwell equations, and to describe astrophysical phenomena in stars.

We need to restrict the gravitational potentials or the energy momentum tensor to solve the Einstein–Maxwell field equations. Here we take into account charged anisotropic matter with a conformal Killing vector in spacetime. The connection relating the metric functions established by Manjonjo et al. [24] and Mafa Takisa et al. [33] is our starting point. We use the form for one of the metric functions that permits the conformal condition in [24] and [33] to be solved. In this paper we find a charged anisotropic solution for stellar matter with the help of a conformal symmetry in spherical symmetric spacetime. In Sect. 2, we give the connection between the metric functions and the Einstein–Maxwell field equations. A new exact charged anisotropic solution is found in Sect. 3. Some physical conditions for acceptability of the compact star and the model parameter constraints are given in Sect. 4. We find stellar masses and radii for particular pulsars PSR J1614-2230, Vela X-1, PSR J1903+327 and Cen X-3. Our obtained results are tabulated in Tables 1 and 2. Graphical plots for the matter variables in the stellar model are presented in Sect. 5. A detailed study of the physical features is undertaken and throughout we compare our new charged results with the earlier uncharged anisotropic model. In Sect. 6 a brief conclusion is made.

2 The model

The line element for a static spherically symmetric interior matter distribution can be given as

where the functions \(\nu (r)\) and \(\lambda (r)\) are the gravitational potentials. The fluid 4-vector is comoving and can be written as \(u^a = e^{-\nu } \delta ^a_0\) for the metric (1). For charged anisotropic distributions, the charged matter tensor can be taken as

with \(\rho , p_{r}\) and \(p_{t}\) and E being the energy density, radial pressure, tangential pressure and electric field respectively. The anisotropy is defined by \(\Delta =p_r - p_t\). For equal radial and tangential pressures, \(\Delta =0\) and the pressure is isotropic. From (1) and (2) the Einstein–Maxwell system of equations may be written as

where \('\equiv \frac{d}{dr}\) and \(\sigma \) is the proper charge density. In our work we are using units where \(G = c =1\).

The charged field equations (3) are difficult to integrate in general. In this approach the existence of a conformal symmetry leads to an exact solution. For a conformal symmetry \( \mathbf {X} \) to exist the metric tensor field \( g_{ab}\) is Lie dragged to give the condition

In Eq. (4), \({\mathcal {L}}_ \mathbf X \) is the usual Lie derivative operator with \(\psi (x^a)\) being the conformal killing vector. Static spherically geometries admitting a conformal killing vector have been fully analysed by Manjonjo et al. [24] by extending the results in Maartens et al. [21, 22] and Moopanar and Maharaj et al. [34, 35]. The basis of these papers is the presence of conformal Killing vector in the form

which is spherically symmetric with the nonstatic conformal function \( \psi = \psi (t,r) \). The presence of a conformal Killing vector \( \mathbf {X} \) in (5) leads to a particular connection between the metric functions \( e^{2 \lambda (r)} \) and \( e^{2 \nu (r)} \). Manjonjo et al. [24] show that the conformal symmetry gives the gravitational potential

where B, k and l are constants. Then the spacetime is conformally flat when \( k=0 \). Non-conformally flat models correspond to \(k\ne 0\). We take the functional form (5) as our starting point to find a charged anisotropic star.

The metric function (6) permits us to express the field equations (3) in the similar form

All the matter variables in (7) are defined in terms of metric function, namely \( e^{2 \lambda } \). An assumed form for \( \lambda (r) \) will produce to an exact solution of Einstein–Maxwell field equation (7) after integration. We show that this is possible in the next section. The mass of a charged compact star is defined by

which is contained within a radius r, and also depends on the electric field E.

3 Exact solution

The function \(e^{\lambda }\) is chosen in order to integrate equation (6) and generate a solution to the Einstein–Maxwell system. This particular choice is taken so that both metric functions remain regular at the centre \(r = 0\). We make the following choice for the potential \(e^{\lambda }\) and the electric field E. For the potential we take

were b is a constant. The electrical field is taken to have the functional form

where s, d and f are constants. Using Eq. (6) we get the second potential

At the centre of the star \( r=0 \) the potentials are regular. The electric field E is regular and bounded the interior and generates physically reasonable profiles. we note that \(E=0\) at \(r=0\) which is necessary for stability. When \(s=0\) we regain the uncharged results of Mafa Takisa et al. [33].

Then utilizing the functions (10) and (11), an exact solution to the Einstein–Maxwell system (7) can be found. The matter variables have the form

where for notational simplicity, we let \( n = e^{2l} \) . The system (12) represents the interior of a charged anisotropic compact object with conformal symmetry. For the above density and the electric field, the mass function (8) becomes

from the definition (8).

4 Physical features of the stellar model

4.1 Regularity conditions inside and at the boundary \(r=\mathcal R\)

For regularity and physical acceptability throughout the star, the model should satisfy certain requirements. These include:

-

A.1.

The metric functons \(e^{2\nu }\) and \(e^{2\lambda }\) and the matter variables \(\rho , p_r\), \(p_t\) should be positive at the centre and continious in the interior of the star; at the centre \(\rho , p_r\) and \(p_t\) must be bounded: \(\rho (r=0)=\rho _{c}\), \(p_r(r=0)={p_r}_{c}\) and \(p_t(r=0)={p_t}_{c}\); the gradients are decreasing with \(\rho '< 0\), \({p_r}'<0\) and \({p_t}'<0\) inside the star. The anisotropy at the centre must vanish so that \(\Delta (r=0)=0\), \(p_t = p_r\).

-

A.2.

For a stable configuration it is necessary that the speed of sound is less than the speed of light. This means that \(0\le v^2_r=\frac{d p_r}{d \rho }\le 1\) and \(0\le v^2_t=\frac{d p_t}{d \rho }\le 1\) inside the star. To avoid cracking or overturning of the star we must have \( -1<v_t^2 -v_r^2<0\), \( 0<v_r^2 -v_t^2<1\). Another condition that may be used for the stability is the condition on the adiabatic index \(\Gamma =\dfrac{\rho +p_r}{p_r}\dfrac{d\rho }{dp_r}>\dfrac{4}{3}\).

-

A.3.

The equilibrium condition for stability of the star is usually considered in relation to the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff (TOV) equation. The TOV equation can be written as

$$\begin{aligned} {p_r}' = -\nu ^{\prime }(\rho +p_r) + \frac{2}{r}(p_t - p_r)+ \sigma E e^{\lambda }. \end{aligned}$$(14)Let us define

$$\begin{aligned} F_g= & {} -\nu ^{\prime }(\rho +p_r), \quad F_h = -\frac{d p_r}{d r},\\ F_a= & {} \frac{2}{r}\left( p_t-p_r\right) , \quad F_e = \sigma E e^{\lambda }, \end{aligned}$$where \(F_g\), \(F_h\), \(F_a\) and \(F_e\) are referred to as gravitational, hydrostatic, anisotropic and electric forces respectively. Then (14) is given by

$$\begin{aligned} F_g + F_h + F_a +F_e=0, \end{aligned}$$(15)so that sum of the forces is zero giving an anisotropic charged gravitating sphere in equilibrium.

-

A.4.

Inside the star, the dominant energy conditions imply that \(\rho - p_r\ge 0\), \(\rho - p_t\ge 0\) and \(\rho - p_r -2 p_t\ge 0\). The metric quantities \(e^{2\lambda }\) and \(e^{2\nu }\) at the boundary \(r=\mathcal R\) must match to the Reissner–Nordstr\(\ddot{o}\)m exterior metric:

(16)

(16)The pressure \(p_r\) should vanish at the stellar surface

$$\begin{aligned} p_r(\mathcal{R})=0. \end{aligned}$$(17)Smooth matching of the electric field E across the star boundary gives

$$\begin{aligned} Q^{2}(\mathcal{R})= E^2 \mathcal{R}^{4}. \end{aligned}$$(18) -

A.5.

The mass-radius ratio and the surface redshift are important to describe the physics quantities. The maximum limit of the mass-radius ratio for a charged compact star is given by Andréasson [36]. The requirement for charged star is

. For a realistic charged compact object, the surface redshift upper bound reads $$\begin{aligned} Z_s(\mathcal{R})=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1-\frac{2M(\mathcal{R},E)}{ \mathcal{R}}}}-1 \le 5.221, \end{aligned}$$(19)

. For a realistic charged compact object, the surface redshift upper bound reads $$\begin{aligned} Z_s(\mathcal{R})=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1-\frac{2M(\mathcal{R},E)}{ \mathcal{R}}}}-1 \le 5.221, \end{aligned}$$(19)

as given by Ivanov [37].

4.2 Model parameter constraints

The regularity of the model depends on the choice of the parameters given in the physical quantities discussed in Sect. 4.1. These values constraint the model. The parameter values ensure that the model is regular at the centre and throughout the star. We must use the value \(k=0\) in the energy density (12a) for regular centre. Also at the centre \(r = 0\) we generate the parameter values

The central values in (20) constraint the parameter n to the interval \(\frac{\sqrt{5}}{2}< n < \sqrt{2} \).

We name a new constant \(\sqrt{H}=\frac{B}{2 \sqrt{b} e^l}\) and use the three boundary conditions (16)–(17) with five unknowns \(M, \mathcal{R}, n, b\) and H. We can write particular parameters in terms of the remaining parameters. The physically relevant model quantities are the mass M and the radius \(\mathcal{R}\), and the model parameters n and b of a compact object in the electric field E.

We first express \(\mathcal{R}\), M in terms of n, b and E. We obtain the relationship

which is the radius of star. In addition we obtain the other relationship

which represents the total mass of the stellar object. Equation (22) constrains the parameter b to the interval \(0<b<\frac{2}{\mathcal{R}^2}\). The parameter H can be expressed in terms of n, b and E as

where H is a constant scaling in the static stellar charged body. Then the recipe for the physical study in our new model can be given as follows: choose the central density \(\rho _c=\frac{3b}{4\pi }\) and central pressure \({p_r}_c =\frac{(n - 1)b}{2\pi }\) with n lying in the range \(\frac{\sqrt{5}}{2}< n < \sqrt{2} \) and \(0<b<\frac{2}{\mathcal{R}^2}\); calculate the radius \(\mathcal{R}\) using (21); use (22) to calculate the mass M; the parameter H can be obtained from (23). The remainder of the matter variables then can be calculated. Secondly, we can express b and n in terms of the radius \(\mathcal{R}\), the mass M and the electric field E. We get

with the parameter b associated with the central density \(\rho _c\). The parameter n is given by

where the parameter n is linked to the central pressure \({p_r}_c\) and the matter variables except the central density. The scaling parameter H can be written in the form

where

In Eqs. (24)–(26) we note the mass \(M< \frac{\mathcal{R}}{2}\) and \(M \ne \frac{4 \mathcal{R}}{9}\). Then the recipe for the physical study in our model can be given as follows: choose the radius \( \mathcal {R} \) and mass M for particular star such that \(M< \frac{\mathcal{R}}{2}\) and \(M \ne \frac{4 \mathcal{R}}{9}\); calculate b using (24); use (25) to calculate n checking that \(\frac{\sqrt{5}}{2}< n < \sqrt{2} \) and \(0<b<\frac{2}{\mathcal{R}^2}\) is satisfied; the parameter H can be obtained from (26). The remaining matter variables then can be calculated.

5 Physical analysis

For a physical study of our model, it is interesting to investigate the effect of the electric charge on the conformal stellar structure. To investigate the features of the charged anisotropic model, we take four pulsars PSR J1614-2230, Vela X-1, PSR J1903+327 and Cen X-3, also used in the previous study of Mafa Takisa et al. [33]. We select the similar maximum values of electric field found in the study of Mafa Takisa et al. [38], where \(E=4.91059\times 10^{20}~\text {V m}^{-1}\) in MKSA units which is equivalent to \(E=1.637\times 10^{16}~\text {Statvolt cm}^{-1}\) in CGS units. We also use the Eqs. (21)–(23) with \(b=0.0032063~\text {km}^{-2}\), \(n=1.20921\) for PSRJ 1614-2230. These values arise in the works of Mafa Takisa et al. [33] for the uncharged conformal model. We observe that the scaling parameter \(\tilde{s}\) in the electric field has the dimension of length\(^{-3}\). To take into account the physical units and dimensional homogeneity in the electric field, we make the following transformation

where \(\mathcal{T}\) is a parameter with dimension of length. We use the Eq. (18) with \(E=1.637\times 10^{16}~\text {Statvolt cm}^{-1}\) which corresponds to the parameter values of \(\tilde{s}=4\), \(d=45\), \(f=0.02~ \text {km}^{-2}\) and \(\mathcal{T}=7.87~ \text {km}^{-2}\). We define \(M_{obs}(M_{\bigodot })\) and \(M_{pred}(M_{\bigodot })\) as the observed and calculated mass respectively. The values for the mass and the radius are \(M=2.13 \pm 0.03 ~M_{\bigodot }\), radius \(\mathcal{R}=10.49\pm 0.19~\text {km}\) and \(H=0.254673\) for the charged case. The corresponding central density, the surface density and central radial and tangential pressures are respectively \(\rho _{c}=1.031 \times 10^{15}~\text {g cm}^{-3}\), \(\rho _{\mathcal{R}}=9.69 \times 10^{14}~\text {g cm}^{-3}\) and \({p_r}_c={p_t}_c=1.205 \times 10^{35}~ \text {dyne cm}^{-2}\).

In order to generate masses and radii of the remaining stars Vela X-1, PSR J1903+327 and Cen X-3, we allow the parameters b, n and H in (21)–(23) to vary. The calculated values are displayed in Table I and Table II in which rows with parentheses represent the charged case. We note that due to the effect of the repulsive force, the charged stars have increased mass and increased radius compared to the uncharged case as we should expect. This behaviour is similar to the work of Ray et al. [39]. Also it is interesting to mention that the presence of the electric field increases the surface gravitational redshift; therefore an observer will detect a more distant compact distribution compared to the uncharged scenario. We remark that even in the charged case, the central density and central pressures decreases with the decrease of the mass; this feature was also reported in the works of Mafa Takisa et al. [33, 38, 40]. The compactification factor \(\frac{M}{\mathcal{R}}\) and the surface redshift increase for all four pulsars compared to the uncharged case. Some of these features are comparable to the work of Sharma and Ratanpal [41], Singh et al. [42] and Kileba Matondo et al. [43].

We notice that both uncharged and charged cases, the central density is in the order of a few times \(10^{15} \text {g cm}^{-3}\) which is relevant for a charged anisotropic stellar object as pointed out by Ruderman [44]. The surface density is approximately in the order of \(10^{14}~ \text {g cm}^{-3}\) and the gravitational redshift is in a realistic range \((0.4274\pm 0.1492)-(0.518 \pm 0.1172)\). This range is still close to the values found by Böhmer and Harko [45], Rahaman et al. [46, 47] and Kileba Matondo et al. [43]. The value of the stellar radius \(\mathcal{R}\) is the range of \((9.68 \pm 0.12) -( 10.49\pm 0.19) ~\text {km}\), and the mass in the range of \((1.63\pm 0.07)-(2.13\pm 0.03)~M_{\bigodot }\). The redshift values are consistent with strange stellar objects which have a compactification factor higher than neutron stars with the redshift upper bound \(Z_s \le 5.211\) as pointed out by Ivanov [37]. We note that the compactification factor is in the range of \(\frac{M}{R}\) \(\sim \) \(\frac{1}{10}\) to \(\frac{1}{4}\) which corresponds to neutron stars and ultra-compact stars as pointed out by Mafa Takisa [48] and Kileba Matondo [43]. The Andréasson [36] requirement for charged cases  in Table 1 are satisfied. Similar mass values were obtained by Gangopadhyay et al. [49] and Mafa Takisa et al. [33, 38, 40] and Kileba Matondo [43]. The compactification factor

in Table 1 are satisfied. Similar mass values were obtained by Gangopadhyay et al. [49] and Mafa Takisa et al. [33, 38, 40] and Kileba Matondo [43]. The compactification factor  is in the range of neutron stars and ultracompact stars.

is in the range of neutron stars and ultracompact stars.

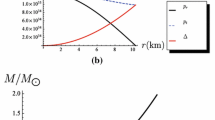

For qualitative understanding of the behaviour of the matter variables inside the star, we have plotted several matter variables in different Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15. We use two imput values of electric field, \(E=1.637\times 10^{16}~\text {Statvolt cm}^{-1}\) corresponds to \(\tilde{s}=4\) and upper bound \(E=2\times 10^{16}~\text {Statvolt cm}^{-1}\) corresponds to \(\tilde{s}=8\). For the values of the scaling parameter \(4<\tilde{s}<8\), the results are similar to \(\tilde{s}=4\). The difference appears at the upper bound value \(\tilde{s}=8\), which value displays unusual profiles in the anisotropy as showed in the zoom box in Fig. 4. For physical acceptability of our charged model, we consider the value \(\tilde{s}=4\).

5.1 Regularity and reality conditions

The regularity and reality conditions required that the energy density, radial pressure, tangential pressure \(\rho \), \(p_r\), \(p_t\), to be positive at the centre and continuous in the interior of the star. For the formation of more compact objects, the anisotropy \(\Delta \) must vanish at the centre and be positive throughout the stellar structure. From our Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4 the the energy density, radial pressure and tangential pressure profiles are regular and well behaved within the star in conformity with regularity requirements. The energy density in Fig. 1 is regular, decreasing and remains finite. In Figs. 2, 3, 4 we show profiles for the radial, tangential pressures and the anisotropy. We note that both tangential and radial pressures are monotonic decreasing within the star and the radial pressure vanishes at the surface. The tangential pressure remains positive throughout the star. The anisotropy is finite at the centre and remains positive within the star for \(\tilde{s}=4\), and consequently the anisotropic force is repulsive in nature as stated by Gokhroo and Mehra [6]. On the other hand for \(\tilde{s}=8\), the anisotropy decreases and becomes negative and then increases and then becomes positive as displayed in the zoom box in Fig. 4.

5.2 Energy and equilibrium conditions

5.2.1 Energy condition

The charged stellar object should satisfy the following energy conditions: dominant energy condition (DEC): \(\rho - p_r\ge 0\) and \(\rho - p_t\ge 0\). Strong energy condition (SEC): \(\rho - p_r -2 p_t\ge 0\). In Fig. 5, the energy conditions \(\rho - p_r\), \(\rho - p_t\) and \(\rho - p_r -2 p_t\) are plotted, they remain positive which indicates that the energy conditions are not violated in our model.

5.2.2 Equilibrium condition

Equilibrium condition for a charged anisotropic star is subject to gravitational force (\(F_g\)), hydrostatic force (\(F_h\)), anisotropic force (\(F_a\)), electric force (\(F_e\)) and their sum \(F_g+F_h+ F_a+ F_e=0\). The profiles of gravitational, hydrostatic, anisotropic and electric forces presented in Fig. 6, show that anisotropic, hydrostatic and electric forces are positive and balanced by the negative gravitational force. It is interesting to see that the sum of all the forces is equal to zero indicating that equilibrium for the static charged anisotropic stellar object is satisfied.

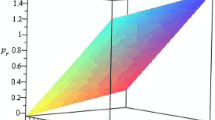

5.3 Causality conditions and stability

5.3.1 Causality condition

The speed of sound inside a fluid stellar matter is an important property to investigate. For a stable anisotropic compact star, the square of radial and tangential speeds of sound should comply with \(0 \le v^2_r \le 1\) and \(0 \le v^2_t \le 1\).

The square of the radial and tangential speeds of sound \(v^2_r\), \(v^2_t\) are plotted in Fig. 7, and they satisfy the causality requirement. The radial speed of sound is great than the tangential speed of sound throughout the star. Therefore, the radial and tangential speeds in our model satisfy the causality conditions \(0 \le v^2_r \le 1\) and \(0 \le v^2_t \le 1\).

5.3.2 Stability conditions

Based on the Herrera cracking concept, Abreu et al. [50] demonstrated that one of the stability conditions throughout the stellar object can be identified as a function of the difference of the radial and tangential speeds. We have \(1\le v^2_t - v^2_r\le 0\) for the stable region and \(0\le v^2_t - v^2_r \le 1\) for the unstable region. Also, the criterion of stability given by the adiabatic index \(\Gamma _r\) and \(\Gamma _t\) which is the ratio of two specific heats and should be bigger than \(\frac{4}{3}\) for stability [7].

In Fig. 8 we present the the difference of the radial and tangential speeds \(v^2_r-v^2_t\) and \(v^2_t-v^2_r\). It is expected that \(- 1\le v^2_t - v^2_r\le 0\) represents a stable region and \(0\le v^2_t - v^2_r \le 1\) an unstable region. From Fig. 8, we can see that \(v^2_r-v^2_t\) within the star lies between 0 and 1 and \(v^2_t-v^2_r\) lies between -1 and 0.

We display the radial and tangential adiabatic indices in Fig. 9. The profiles show that the radial and tangential adiabatic indices \(\Gamma _r\) and \(\Gamma _t\) are great than \(\Gamma =\frac{4}{3}\) everywhere within the stellar interior. Thus our charged model is stable.

5.4 Mass and gravitational redshift

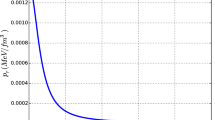

5.4.1 Mass

The mass central density relationship is useful in determining the static hydrostatic stability of realistic compact objects.

The stellar mass versus central density is provided in Fig. 10. For the upper bound radius value \(\mathcal{R}=10.49 \pm 0.19~\text {km}\), the mass increases with central density and reaches the turning point at the central density value of \(\rho _c=3.030 \times 10^{15} \text {gcm}^{-3}\) with corresponding value of mass \(M=3.69\pm 0.03~M_{\bigodot }\) for \(\tilde{s}=4\). We notice an increase in the stellar mass due to the presence of electric charge. Similar behaviour is reported in the investigation of Ray et al. [39]. The stellar densities with corresponding masses located on the left of the turning point are in the stable region and the unstable region corresponds to the right side of the turning point. Interestingly, all our four pulsars PSR J1614-2230 with central density \(\rho _c=1.031\times 10^{15}~\text {gcm}^{-3}\) and corresponding mass \(M=2.13\pm 0.03~M_{\bigodot }\), Vela X-1 with central density \(\rho _c=0.997\times 10^{15}~\text {gcm}^{-3}\) and corresponding mass \(M=1.93\pm 0.07~M_{\bigodot }\), PSR J1903+327 with central density \(\rho _c=0.980\times 10^{15}~\text {gcm}^{-3}\) and corresponding mass \(M=1.820\pm 0.019~M_{\bigodot }\) and Cen X-3 with central density \(\rho _c=0.949\times 10^{15}~\text {gcm}^{-3}\) and corresponding mass \(M=1.63\pm 0.07~M_{\bigodot }\) listed in the two tables are located in the stable region.

The mass versus radius relationship is presented in Fig. 11, the mass is well behaved and increases with the increase of the radius for both uncharged and charged cases. There is increase of mass for the charged case due to the presence of electric charge.

5.4.2 Redshift

The existence of a limiting value of the mass-radius ratio leads to limiting values for other physical quantities of observational interest. One of these quantities is the surface gravitational redshift of the compact object. For a dense compact stars electrically charged to a certain extent, the light rays emitted from its surface can be significantly shifted toward the red, which translates to an increase value of the gravitational redshift.

The surface gravitational redshift versus the mass is plotted in Fig. 12, which is an increasing profile for both the uncharged and the charged case. According to Ivanov [37] for a charged anisotropic star the constraint on the surface redshift is \(Z_s=5.211\). Therefore Fig. 12 displays the upper bound limit for the charged stellar maximum mass with numerical value of surface redshift \(Z_s=5.211\) and the mass \(M=3.69\pm 0.03M_{\bigodot }\) for \(\tilde{s}=4\). This upper bound limit is consistent with the upper limit of Fig. 10.

The surface gravitational redshift versus the central density is displayed in Fig. 13, it is an increasing profile with upper bound central density of \(\rho _c=1.178\times 10^{15}~\text {gcm}^{-3}\) at surface redshift \(Z_s=5.211\). This value is within the stable region of Fig. 10.

In Fig. 14 we display the surface redshift versus radius. Interestingly, the surface redshift is an increasing function with upper bound limit of the radius set at \(\mathcal{R}=11.11\pm 0.19~\text {km}\) for the maximum redshift value of \(Z_s=5.211\) for our charged compact model.

The central gravitational redshift versus radius is display in Fig. 15, with a monotonically decreasing profile for both uncharged and charges cases.

6 Conclusion

In this investigation we have considered a conformal symmetry model of a compact anisotropic star with charge. We demonstrated an exact solution to the Einstein–Maxwell equations with conformal symmetry. We examined in detail the charged exact solution for the conformally flat case when parameter \(k=0 \). Furthermore, in order to ensure good behaviour in the matter variables at the centre and throughout the stellar object, various parameter constraints were taken into account. We regained different masses and radii of observed compact objects, such as PSR J1614-2230, Vela X-1, PSR J1903+0327 and Cen X-3. We achieved this by choosing specific values of central density, central pressure and electric field according to the literature containing previous investigations of Ray et al. [39] and Mafa Takisa et al. [38]. We observe that the central density decreases with the decrease of the mass for both the uncharged and charged cases. Similar behaviour of decreasing central density was also mentioned in the work of Mafa Takisa et al. [33, 38, 40] and Murad [51]. We also plotted the matter variables for the stellar object. Our analysis shows that the matter variables and the metric potentials are regular throughout the star and well behaved. Interestingly our charged model puts an upper bound on maximum stellar mass, central density and stellar radius. The causality and the stability conditions are met within the stellar structure. The compactification values and surface redshift are in agreement with required values.

Data Availability Statement

This manuscript has no associated data or the data will not be deposited. [Authors’ comment: All data generated during this study are contained in this published article.]

References

B.W. Bonnor, Z. Phys. 160, 59 (1960)

R. Ruderman, Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 10, 427 (1972)

V. Canuto, in Proceedings of the Solvay Conference on Astrophysics and Gravitation, Brussels, 1973 (Editions de l’Université, Brussels, 1974)

R. Bowers, E. Liang, Astrophys. J. 188, 657 (1974)

L. Herrera, J. Ponce de Leon, J. Math. Phys. 26, 2302 (1985)

M.K. Gokhroo, A.L. Mehra, Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 26, 75 (1994)

L. Herrera, N.O. Santos, Phys. Rep. 286, 53 (1997)

M.K. Mak, T. Harko, Proc. R. Soc. A 459, 393 (2003)

H. Hernandez, L.A. Nunez, Can. J. Phys. 82, 29 (2004)

V.O. Thomas, B.S. Ratanpal, P.C. Vinodkumar, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 14, 85 (2005)

S.K. Maurya, Y.K. Gupta, S. Ray, B. Dayanandan, Eur. Phys. J. C 75, 225 (2015)

S.K. Maurya, Y.K. Gupta, B. Dayanandan, S. Ray, Eur. Phys. J. C 76, 266 (2016)

K.N. Singh, N. Pant, Eur. Phys. J. C 76, 524 (2016)

B.S. Ratanpal, V.O. Thomas, D.M. Pandya, Astrophys. Space Sci. 361, 65 (2016)

B. Dayanandan, S.K. Maurya, T.T. Smitha, Eur. Phys. J. A 53, 141 (2017)

L. Herrera, J. Jimenez, L. Leal, J. Ponce de Leon, J. Math. Phys. 25, 3274 (1984)

L. Herrera, J. Ponce de Leon, J. Math. Phys. 26, 778 (1985)

L. Herrera, J. Ponce de Leon, J. Math. Phys. 26, 2018 (1985)

L. Herrera, J. Ponce de Leon, J. Math. Phys. 26, 2302 (1985)

R. Maartens, M.S. Maharaj, J. Math. Phys. 31, 151 (1990)

R. Maartens, S.D. Maharaj, B.O.J. Tupper, Class. Quantum Gravity 12, 2577 (1995)

R. Maartens, S.D. Maharaj, B.O.J. Tupper, Class. Quantum Gravity 13, 317 (1996)

B.O.J. Tupper, A.J. Keane, J. Carot, Class. Quantum Gravity 29, 145016 (2012)

A.M. Manjonjo, S.D. Maharaj, S. Moopanar, Eur. Phys. J. Plus 132, 62 (2017)

A.M. Manjonjo, S.D. Maharaj, S. Moopanar, Class. Quantum. Gravity 35, 4 (2017)

M.K. Mak, T. Harko, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 13, 149 (2004)

M. Esculpi, E. Aloma, Eur. Phys. J. C 67, 521 (2010)

F. Rahaman, S.D. Maharaj, I.H. Sardad, K. Chakraborty, Mod. Phys. Lett. A 32, 1750053 (2017)

D. Shee, F. Rahaman, B.K. Guha, S. Ray, Astrophys. Space Sci. 361, 167 (2016)

P. Bhar, Eur. Phys. J. C 75, 123 (2015)

A.A. Usmani, F. Rahaman, S. Ray, K.K. Nandi, P.K.F. Kuhfittig, S.A. Rakib, Z. Hasan, Phys. Lett. B 701, 388 (2011)

A. Banerjee, F. Rahaman, S. Islam, M. Govender, Eur. Phys. J. C 76, 34 (2016)

P. Mafa Takisa, S.D. Maharaj, A.M. Manjonjo, S. Moopanar, Eur. Phys. J. C 77, 713 (2017)

S. Moopanar, S.D. Maharaj, J. Eng. Math. 82, 125 (2013)

S. Moopanar, S.D. Maharaj, Int. J. Theor. Phys. 49, 1878 (2010)

Commun Andréasson, Math. Phys. 288, 715 (2009)

B.V. Ivanov, Phys. Rev. D 65, 104011 (2002)

P. Mafa Takisa, S. Ray, S.D. Maharaj, Astrophys. Space Sci. 350, 733 (2014)

S. Ray, A.L. Espindola, M. Malheiro, J.P.S. Lemos, V.T. Zanchin, Phys. Rev. D 68, 084004 (2003)

P. Mafa Takisa, S. D. Maharaj Maharaj, S. Ray, Astrophys. Space Sci. 354, 463 (2014)

R. Sharma, B.S. Ratanpal, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 22, 1350074 (2013)

K.N. Singh, N. Pant, M. Govender, Indian J. Phys. 90, 1215 (2016)

D .Kileba Matondo, P. Mafa Takisa, S.D. Maharaj, S. Ray, Astrophys. Space Sci. 362, 186 (2017)

R. Ruderman, Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 10, 427 (1972)

C.G. Böhmer, T. Harko, Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 39, 757 (2007)

F. Rahaman, R. Sharma, S. Ray, R. Maulick, I. Karar, Eur. Phys. J. C 72, 2071 (2012)

F. Rahaman, N. Paul, S.S. De, S. Ray, Md A.Kayum Jafry, Eur. Phys. J. C 75, 564 (2015)

P. Mafa Takisa, S.D. Maharaj, Astrophys. Space Sci. 343, 569 (2013)

T. Gangopadhyay, S. Ray, X.-D. Li, J. Dey, M. Dey, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 431, 3216 (2013)

H. Abreu, H. Hernández, L.A. Núñez, Class. Quantum Gravity 24, 4631 (2007)

M.H. Murad, Astrophys. Space Sci. 361, 20 (2016)

Acknowledgements

PMT, LLL thank the the University of South Africa and National Research Foundation for financial support. SDM acknowledges that this work is based on research supported by the South African Research Chair Initiative of the Department of Science and Technology and the National Research Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Funded by SCOAP3

About this article

Cite this article

Mafa Takisa, P., Maharaj, S.D. & Leeuw, L.L. Effect of electric charge on conformal compact stars. Eur. Phys. J. C 79, 8 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-018-6519-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-018-6519-0

. For a realistic charged compact object, the surface redshift upper bound reads

. For a realistic charged compact object, the surface redshift upper bound reads