Abstract

In this paper we utilise the Krori–Barua ansatz to model compact stars within the framework of Einstein–Gauss–Bonnet (EGB) gravity. The thrust of our investigation is to carry out a comparative analysis of the physical properties of our models in EGB and classical general relativity theory with the help of graphical representation. From our analysis we have shown that the central density and central pressure of EGB star model is higher than the GTR star model. The most notable feature is that for both GTR and the EGB star model the compactness factor crosses the Buchdahl (Phys Rev 116:1027, 1959) limit.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Modeling stars within the framework of Einstein’s theory of gravity has occupied researchers for a century. The first exact solution of the Einstein field equations was obtained by Schwarzschild in 1916. This solution describes the exterior vacuum spacetime of a spherically symmetric body. In the same year, Schwarzschild presented the interior solution describing the gravitational behavior of a uniform density sphere [1]. Since then, hundreds of exact solutions of the classical field equations describing static fluid spheres have been obtained in which the energy-momentum tensor describing the matter distribution incorporated anisotropy, bulk viscosity, electromagnetic field, scalar field, dark energy, and the cosmological constant. Various techniques ranging from ad hoc assumptions of the gravitational potentials, specifying an equation of state, spacetime symmetry, conformal flatness, to name a few, have been employed to solve the field equations [2,3,4,5,6]. A systematic study of the physical viability of these solutions have been carried out by Delgaty and Lake [7] who showed that only a few classes of available solutions are capable of describing realistic stellar configurations. Many of these results have later been extended to higher dimensions [8]. Interestingly, the dimensionality of spacetime apparently influences the stability of these fluid spheres. With astronomical observations of compact objects becoming more precise and data sets of neutron stars and strange stars being readily available, a new and invigorated search for exact solutions of the 4-D Einstein field equations are being carried out. In the recent past, there has been an explosion of such solutions describing compact objects which adequately fit observations. Observational data on mass-to-radius ratio, redshift and luminosity profiles are some of the key characteristics for testing the physical validity of these models. One of the objectives of these models is to fine-tune the equation of state in the high density regime. Apart from classical barotropic equation of state \(p = \omega \rho \), where \(\omega \) is a constant, many models are being developed based on our current understanding of particle physics. The MIT bag model first proposed by Chodos et al. [9] has been widely used in modeling ‘strange stars’ composed of u, d and s quarks [1, 10, 11]. The Chaplygin equation of state [12] incorporating dark energy into the stellar fluid configuration has been employed to model compact objects ranging from quark stars through to neutron stars. While these models are successful in accounting for observational data of compact objects, one cannot ignore the fact that gravitational behavior (metric functions) and thermodynamical behavior (energy-momentum tensor) can be tweaked by hand to align them with observations. Therefore, the fundamental question to be asked is whether classical general relativity is sufficient to account for observed stellar characteristics. In other words, can certain, if not all, stellar features reside in higher-order theories of gravity?

The behavior and dynamics of the gravitational field can be extended to higher dimensions in a natural way. An elegant and fruitful generalization of classical general relativity is the so-called Einstein–Gauss–Bonnet (EGB) gravity which arises from the incorporation of an additional term to the standard Einstein–Hilbert action, which is quadratic in the Riemann tensor. Varying this additional term with respect to the metric tensor only produces a system of second-order equations which are compatible with classical general relativity [13]. In standard 4-D, EGB and Einstein gravity are indistinguishable. The departure from the standard 4-D Einstein gravity occurs in higher dimensions. There have been many interesting results in the 5-D EGB theory ranging from the vacuum exterior solution due to Boulware and Deser [14] through to generalization of the Kerr–Schild vacuum solution. The dynamics of gravitational collapse and the resulting end-states in EGB gravity has also received widespread attention. The study of a spherically symmetric inhomogeneous dust (as well as null dust) in EGB gravity with \(\alpha > 0\) was shown to alter the causal structure of the singularities compared to the standard 5-D general relativistic case [15]. The result is, in fact, a counter example of the cosmic censorship conjecture. The study of Vaidya radiating black-holes in EGB gravity has revealed that the location of the horizons is changed as compared to the standard 4-D gravity [16]. The universality of Schwarzschild’s uniform density solution was established using EGB gravity and later extended to Lovelock gravity [17, 18]. The Buchdahl inequality for static spheres has been extended to 5-D EGB gravity [19]. It was shown that the sign of the Einstein–Gauss–Bonnet coupling constant plays a crucial role on the mass-to-radius ratio. An interesting result of the investigation was that one could pack in more mass in 5-D EGB compared to standard 4-D Einstein gravity to achieve stability [20]. Despite the non-linearity of the field equations, several exact solutions in 5-D EGB gravity have recently been found. The classic isothermal sphere has been generalized to 5-D EGB gravity. Just as in the 4-D case, the 5-D EGB models exhibit a linear barotropic equation of state [21, 22].

In 4-D gravity, one of the exact solutions which has got much attention is the Krori and Barua [23] solution. It is a solution of the Einstein–Maxwell system describing a spherically symmetric charged fluid sphere. The gravitational potentials are finite everywhere within the stellar distribution and the matter variables are well behaved [24]. Consequently, the Krori–Barua (KB) solution has been used by many authors to model compact objects within the framework of Einstein’s gravity. Several researchers have utilized various equations of state, ranging from the MIT bag model through to the generalized Chaplygin gas together with the KB ansatz to model compact stars such as \(Her X-1\), \(4U 1820-30\), \(SAX J 1808.4-3658\), \(4U 1728-34\), \(PSR 0943+10\), and \(RX J185635-3754\) [12, 25,26,27]. In this work, we intend to extend the KB solution to 5-D EGB gravity. The motivation for this modification is to analyze the effects, if any, of the EGB term on stability, compactness and other physical features of compact stellar objects.

2 Einstein–Gauss–Bonnet gravity

The Gauss–Bonnet action in five dimensions is written as

where \(\alpha \) is the Gauss–Bonnet coupling constant. The strength of the action \(L_\mathrm{GB}\) lies in the fact that despite the Lagrangian being quadratic in the Ricci tensor, Ricci scalar, and the Riemann tensor, the equations of motion turn out to be second order quasi-linear and compatible with the standard Einstein formalism of gravity. The Gauss–Bonnet term is of no consequence for \(n\le 4\) but is generally nonzero for \(n \ge 5\).

The EGB field equations may be written as

with metric signature \((- + + + +)\) where \(G_{ab}\) is the Einstein tensor. The coupling constant \(\alpha \) is related to the inverse string tension arising from the low energy effective action of string theory and to this end we consider \(\alpha \ge 0\). The Lanczos tensor is given by

where the Lovelock term has the form

In the above formalism we use geometric units with the coupling constant \(\kappa \) set to unity.

3 Field equations

The 5-dimensional line element for a static spherically symmetric spacetime has the standard form

in coordinates (\(x^i = t,r,\theta ,\phi ,\psi \)). For our model the energy-momentum tensor for the stellar fluid is taken to be

where \(\rho \), \(p_r\), and \(p_t\) are the proper energy density, radial pressure, and tangential pressure, respectively. By considering the comoving fluid velocity as \(u^a=e^{-\nu }\delta _0^a\), the EGB field equations (2) yield the following set of independent equations:

where \(\rho \), \(p_r\) and \(p_t\), respectively denote the matter density, radial and transverse pressure of the fluid. Note that a \((\prime )\) denotes the differentiation with respect to the radial coordinate r.

4 A particular solution

We observe that Eqs. (6)–(8) correspond to a system of three linearly independent equations with five unknowns, namely \(\rho \), \(p_r\), \(p_t\), \(\lambda \) and \(\nu \). To analyze behavior of the physical parameters, we assume that the metric potentials are given by the Krori and Barua [23] solution,

where A, B, and C are undetermined constants which can be obtained from the matching conditions.

Consequently, the matter density and the two pressures are obtained:

The anisotropy \(\Delta =p_t-p_r\) is obtained:

5 Exterior spacetime and matching conditions

The static exterior spacetime in 5-D is described by the Einstein–Gauss–Bonnet–Schwarzschild solution [14]

where

In (15) M is associated with the gravitational mass of the hypersphere.

Using continuity of the metric functions and their derivatives, namely \(g_{rr}\), \(g_{tt}\) and \(\frac{\partial g_{tt}}{\partial r}\) across the boundary \(r=R\) we get

Solving the above set of equations we obtain the model parameters as

The values of the model parameters should be such that the system remains regular and well behaved.

6 Features and results

A physically acceptable model should have the following features:

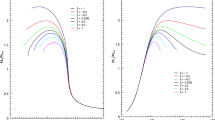

Matter density \(\rho \) plotted against the radial distance r. The description of the curves is as follows: red small dashed line, black medium dashed line, brown long dashed line, blue dot-dashed line and orange solid line for \(\alpha =0,\,\alpha =10,\,\alpha =15,\,\alpha =30\) and \(\alpha =50\), respectively by fixing \(A=0.0042\) and different values of B mentioned in Table 1

Radial pressure \(p_r\) plotted against the radial distance r. The description of the curves is the same as in Fig. 1

Transverse pressure \(p_t\) plotted against the radial distance r. The description of the curves is the same as Fig. 1

Anisotropic factor \(\Delta \) plotted against the radial distance r. The description of the curves is the same as Fig. 1

-

1.

The energy density \(\rho \) and two pressures \(p_r\) and \(p_t\) should be positive inside the star. Also, the radial pressure must vanish at a finite radial distance while the tangential pressure \(p_t\) need not vanish at the boundary. The radial variation of density and pressure have been shown in Figs. 1 and 2, respectively. We have

$$\begin{aligned} \frac{\mathrm{d}\rho }{\mathrm{d}r}= & {} -\frac{3e^{-2Ar^{2}}}{4\pi r^{3}}\left[ e^{Ar^{2}}\left( 4A^{2}r^{2}\alpha +A^{2}r^{4}-Ar^{2}+4A\alpha -1\right) \right. \\&\left. -\,4A\alpha (1+2Ar^{2})+e^{2Ar^{2}}\right] ,\\ \frac{\mathrm{d}p_r}{\mathrm{d}r}= & {} -\frac{3e^{-2Ar^{2}}}{4\pi r^{3}}\left[ e^{Ar^{2}}\left( Ar^{2}+4Ar^{2}\alpha B+ABr^{4}+1+4\alpha B\right) \right. \\&\left. -\,4\alpha B(1+2Ar^{2})-e^{2Ar^{2}}\right] . \end{aligned}$$It is clear that \(\frac{\mathrm{d}p_r}{\mathrm{d}r} < 0\) and \(\frac{\mathrm{d}\rho }{\mathrm{d}r} < 0\), both in EGB gravity and in GTR. It is important to note that EGB predicts higher values for the density and radial pressure as the strength of the EGB coupling constant increases. Figure 3 illustrates the behavior of the tangential pressure as a function of the radial coordinate. We observe a peculiar behavior of the tangential pressure within the core. For some radius \(0 \le r < r_0\) we observe that the tangential pressures in EGB models dominate the tangential pressure in the GTR model. At some radius \(r = r_0\) the tangential pressures are independent of \(\alpha \) and are equal in magnitude. For \(r > r_0\) the tangential pressures decrease with an increase in \(\alpha \), with GTR dominating the EGB models.

-

2.

Figure 4 shows that anisotropy is zero at the centre, i.e., \(\Delta (r=0) = 0\) and it increases toward the surface. We also observe that as \(\alpha \) increases the anisotropy decreases at each interior point of the configuration. The effect of the Einstein–Gauss–Bonnet term is to diminish the relative difference between the radial and tangential stresses. This may be a possible mechanism to achieve pressure isotropy within the stellar interior.

-

3.

Figure 5 shows that the trace of stress tensor \((p_r+2p_t)\) decreases radially outwards both in EGB gravity as in GTR which is a desirable feature for a fluid sphere.

-

4.

For a physically acceptable model, it is expected that the radial sound speed \(v_{r}^{2} (=\frac{\mathrm{d}p_r}{\mathrm{d}\rho })\) and transverse sound speed \(v_{t}^{2} (=\frac{\mathrm{d}p_t}{\mathrm{d}\rho })\) should be causal, i.e., we should have \( 0 < v_{r}^{2} \le 1\) and \( 0 < v_t^2 \le 1\). We have shown graphically that both in EGB gravity and GTR, the causality condition is not violated at any point within the stellar interior (see Figs. 6, 7). It is evident that in EGB gravity, the radial sound speeds take higher values as compared to their GTR counterparts.

\((p_r+2p_t)/\rho \) plotted against radial distance r. The description of the curves is the same as in Fig. 1

Radial sound velocity \(v_{r}^2\) plotted against the radial distance r. The description of the curves is the same as Fig. 1

Transverse sound velocity \(v_{t}^2\) plotted against the radial distance r. The description of the curves is the same as Fig. 1

6.1 Energy conditions

Let us now check whether our anisotropic stellar model satisfies the following energy conditions:

In Figs. 9, 10 and 11, we have shown graphically that all the energy conditions are satisfied for the assumed set of values of the model parameters, in both EGB and GTR models.

\(v_{t}^2-v_{r}^2\) plotted against the radial distance r. The description of the curves is the same as in Fig. 1

\(WEC_r\) plotted against radial distance r. The description of the curves is the same as in Fig. 1

\(\mathrm{WEC}_t\) plotted against radial distance r. The description of the curves is the same as in Fig. 1

Verification of strong energy condition. The description of the curves is the same as in Fig. 1

6.2 Adiabatic index and stability

The stability of a relativistic anisotropic sphere is related to the adiabatic index \(\varGamma \), the ratio of two specific heats is defined by Chan et al. [28],

Bondi [29] has shown that \(\varGamma > 4/3\) is the condition for the stability of a Newtonian sphere and \(\varGamma = 4/3\) being the condition for a neutral equilibrium. This condition changes for a relativistic isotropic sphere, due to the regenerative effect of pressure, which renders the sphere more unstable, and requires a stiffer material to reach the equilibrium. For an anisotropic general relativistic sphere, the situation becomes more complicated, because the stability will depend on the type of anisotropy. For an anisotropic relativistic sphere, the stability condition is given by,

where \(\varGamma _r\) and \(\varGamma _t\) are defined as,

and \(p_{r0}\), \(p_{t0}\), and \(\rho _0\) are the initial radial, tangential, and energy density in static equilibrium. The first and last terms inside the square brackets, the anisotropic and relativistic corrections, respectively, being positive quantities, increase the unstable range of \(\varGamma \) [28, 30]. In Figs. 12 and 13, it has been shown that \(\varGamma _r,\varGamma _t > 4/3\) everywhere within the stellar interior in GRT and in EGB gravity.

The adiabatic index \( \varGamma _r \) plotted against r. The description of the curves is the same as in Fig. 1

The adiabatic index \( \varGamma _t\) plotted against r. The description of the curves is the same as in Fig. 1

To check the stability of the configuration, we follow the cracking (or overturning) method of Herrera [30] which suggests that a potentially stable region is one where the inequality \( v_{t}^{2} - v_{r}^{2} < 0\) holds. In Fig. 8, we have shown the difference of \( v_{t}^{2} -v_{r}^{2}\) do not change sign which clearly indicates that the configuration is stable for the assumed set of values. Moreover, the Andréasson’s condition \(|v_{t}^{2} -v_{r}^{2}|<1\) (Fig. 8) is also satisfied [31] both in GTR as well as in EGB gravity.

In order to test the robustness of our approach in modeling compact objects within the framework of EGB and GTR gravity theories we utilize the following prescription. We observe that we have five unknowns, viz., \(A,\,B,\,M,\,R\) and \(\alpha \) and three equations. Let us fix the radius of the star at \(R=8~\mathrm{km}\) in both EGB and GTR models. We have chosen \(A=0.0042~\mathrm{km}^{-2}\) so that the central density becomes \(\sim ~10^{15}~\mathrm{gm~cm}^{-3}.\) By varying the EGB coupling constant, \(0 \le \alpha \le 50\), we generate corresponding values for the constant B and masses for the respective models. These are presented in the Table 1. It is clear from the figures and the table that there are non-negligible differences between EGB and GTR compact objects. An interesting feature that comes out strongly in this study is that we can pack in more mass for a given radius with increasing EGB coupling constant thus leading to higher densities of compact stars in the EGB formalism. These observations may give us some insight into the nature of matter in higher dimensions.

7 Discussion

Gravitational theories with higher derivative curvature terms developed in the context of string theory in particular, have long been an area of great research attraction. Studies of gravitational behavior in dimensions \(n > 4\) have often been found to yield many non-trivial and interesting results. Of particular interest is the Einstein–Gauss–Bonnet gravity in which the Lagrangian includes a second-order Lovelock term as the higher curvature correction to GTR. Several vacuum solutions in 5-dimensional Einstein–Gauss–Bonnet gravity have been found and applied in astrophysics and cosmology. However, it is extremely difficult to generate interior solutions corresponding to star like systems in higher dimensions due to complex nature of the field equations and lack of sufficient information as regards the equation of state (EOS) of the matter content of the system. In this paper, rather than providing new solutions, we have developed the 4-dimensional Krori and Barua stellar solution in the context of EGB gravity and analyzed the impacts of the higher derivative correction term on the gross physical behavior of a relativistic star. Based on physical requirements, bounds on the model parameters have been identified. Within the admissible bounds, physical characteristics of the solution in EGB gravity have been analyzed. In Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13, we have shown graphicallly impacts of the higher derivative coupling term \(\alpha \) on physically relevant quantities. It is to be noted that the \(\alpha =0\) case corresponds to 5-dimensional Einstein analog of EGB gravity. It turns out that the coupling constant \(\alpha \) in EGB gravity has non-negligible effects on the physical quantities such as energy density and pressure of the star. Implication of our results, in the context of current observational data of relativistic compact stars, needs to be probed further and will be taken up elsewhere.

References

M. Govender, S. Thirukkanesh, Astrophys. Space. Sci. 358, 16 (2015)

K.N. Singh, N. Pant, Astrophys. Space. Sci. 358, 1 (2015)

S. Thirukkanesh, M. Govender, D.B. Lortan, N. Pant, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 24, 1550002 (2015)

P. Mafa Takisa, S.D. Maharaj, Astrophys. Space Sci. 343, 569 (2013)

P. Mafa Takisa, S.D. Maharaj, Astrophys. Space Sci. 361, 262 (2016)

D.K. Matondo, S.D. Maharaj, Astrophys. Space Sci. 361, 221 (2016)

M.S.R. Delgaty, K. Lake, Comput. Phys. Commun. 115, 395 (1998)

P. Bhar, F. Rahaman, S. Ray, V. Chaterjee, Euro. Phys. J. C 75, 190 (2015)

A. Chodos, R.L. Jaffe, K. Johnson, C.B. Thorn, V.F. Weisskopf, Phys. Rev. D 9, 3471 (1974)

R. Sharma, S.D. Maharaj, MNRAS 375, 1265 (2007)

S.A. Ngubelanga, S.D. Mahara, Adv. Math. Phys. 2013, 905168 (2013)

F. Rahaman, S. Ray, A.K. Jafry, K. Chakraborty, Phys. Rev. D 82, 104055 (2010)

M. Wright, Gen. Relat. Gravit. 48, 1 (2016)

D.G. Boulware, S. Deser, Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 2656 (1985)

S. Jhingan, S.G. Ghosh, Phys. Rev. D 81, 024010 (2010)

S.G. Ghosh, D.W. Deshkar, Phys. Rev. D 77, 047504 (2008)

N.K. Dadhich, A. Molina, A. Khugaev, Phys. Rev. D 81, 104026 (2010)

N.K. Dadhich, S. Hansraj, S.D. Maharaj, Phys. Rev. D 93, 044072 (2016)

N.K. Dadhich, Phys. Rev. D. arXiv:1606.01330 (2016)

R. Goswami, S.D. Maharaj, A.M. Nzioki, Phys. Rev. D 92, 064002 (2015)

S. Hansraj, B. Chilambwe, S.D. Maharaj, Euro. J. Phys. C 75, 277 (2015)

S.D. Maharaj, B. Chilambwe, S. Hansraj, Phys. Rev. D 91, 084049 (2015)

K.D. Krori, J. Barua, J. Phys. A 8, 508 (1975)

B.V. Ivanov, Phys. Rev. D 65, 104001 (2002)

G.J.G. Junevicus, J. Phys. A. Math. Gen. 9, 2069 (1976)

V. Varela, F. Rahaman, S. Ray, K. Chakraborty, M. Kalam, Phys. Rev. D 82, 044052 (2010)

F. Rahaman, R. Sharma, S. Ray, R. Maulick, I. Karar, Eur. Phys. J. C 72, 207 (2012)

R. Chan, L. Herrera, N.O. Santos, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 265, 533 (1993)

H. Bondi, Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 281, 39 (1964)

L. Herrera, Phys. Lett. A 165, 206 (1992)

H. Andréasson, Commun. Math. Phys. 288, 715 (2008)

H.A Buchdahl, Phys. Rev. 116, 1027 (1959)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Funded by SCOAP3

About this article

Cite this article

Bhar, P., Govender, M. & Sharma, R. A comparative study between EGB gravity and GTR by modeling compact stars. Eur. Phys. J. C 77, 109 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-017-4675-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-017-4675-2