Abstract

With the non-local observables such as two point correlation function and holographic entanglement entropy, we probe the phase structure of the Born–Infeld–anti-de Sitter black holes. For the case \(bQ>0.5\), where b is the Born–Infeld parameter and Q is the charge of the black hole, the phase structure is found to be similar to that of the Van der Waals phase transition, namely the black hole undergoes a first order phase transition and a second order phase transition before it reaches a stable phase. While for the case \(bQ<0.5\), a new phase branch emerges besides the Van der Waals phase transition. For the first order phase transition, the equal area law is checked, and for the second order phase transition, the critical exponent of the heat capacity is obtained. All these results are found to be the same as that observed in the entropy–temperature plane.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Investigation on phase transition of an AdS space time has attracted attention of many theoretical physicists recently. The main motivation maybe steps from the existence of the AdS/CFT correspondence [1–3], which relates a black hole in the AdS space time to a thermal system without gravity. For in this case, some interesting but intractable phenomena in strongly coupled system become to be tractable easily in the bulk. To probe these fascinating phenomena in field theory, one should employ some non-local observables such as equal time two point correlation function for a scalar operator, Wilson loop, and holographic entanglement entropy, which are dual to the geodesic length, minimal area, and minimal volume individually in the saddle point approximation. It has been shown that these observables can probe the non-equilibrium thermalization behavior [4–15], superconducting phase transition [16–23], and cosmological singularity [24, 25].

In this paper, we intend to use the non-local observables to probe the phase structure of the Born–Infeld–anti-de Sitter black holes. Usually, the phase structure of a black hole is understood from the viewpoint of thermodynamics. For an uncharged AdS black hole, it has been found that there is a first order phase transition between the thermal gas in AdS space and Schwarzschild AdS black holes [26], which was interpreted as the confinement/deconfinement phase transition in the dual gauge field theory later [27]. As it is endowed with charge, the AdS black hole will undergo a Van der Waals-like phase transition before it reaches the stable state in the entropy–temperature plane [28]. Specifically speaking, there exists a critical charge, and for the case that the charge of the black hole is smaller than the critical charge, the black hole undergoes a first order phase transition. When the charge reaches the critical value, the phase transition is a second one, while the charge exceeds the critical charge, there is not phase transition and the black hole is always stable. The Van der Waals-like phase transition can be observed in many circumstances. In [29], it was found that a 5-dimensional neutral Gauss–Bonnet black hole demonstrates the Van der Waals-like phase transition in the \(T-\alpha \) plane, where T is the Hawking temperature and \(\alpha \) is the Gauss–Bonnet coupling parameter. In [30], the Van der Waals-like phase transition was also observed in the \(Q-\Phi \) plane, where Q is electric charge and \(\Phi \) is the chemical potential. Treating the negative cosmological constant as the pressure P and its conjugate as the thermodynamical volume V,Footnote 1 the Van der Waals-like phase transition has also been observed in the \(P-V\) plane recently [31–39].

Very recently, with the entanglement entropy as a probe, [40] investigated the phase structure of the Reissner–Nordström–AdS black hole and found that there was also a Van der Waals-like phase transition in the entanglement entropy–temperature plane.Footnote 2 They also obtained the critical exponent of the heat capacity for the second order phase transition in the neighborhood of the critical points. To further confirm the similarity of the phase structure between the thermal entropy and entanglement entropy, [42] checked Maxwell’s equal area lawFootnote 3 later and found that it held for the first order phase transition in the entanglement entropy–temperature plane. Now [40] has been generalized to the extended phase space [43], massive gravity [44], as well as Weyl gravity [45], and all the results showed that the entanglement entropy exhibited the same phase structure as that of the thermal entropy.

In this paper, besides the entanglement entropy, we will employ the equal time two point correlation function of scalar field to probe the phase structure of the black holes. The equal time two point correlation function is also a non-local probe and it has some similar properties as the entanglement entropy, thus it will be interesting to explore whether this observable can probe the phase structure of the black hole. We choose the Born–Infeld–anti-de Sitter black holes as the gravity model, which is a solution of the Einstein–Born–Infeld action. There have been many works to study phase structure of the Born–Infeld–anti-de Sitter black holes [46–52]. The results showed that both the Born–Infeld parameter b and the charge Q affect the phase structure, and to ensure the existence of a non-extremal black hole, one should impose the condition \(bQ>0.5\) [46]. In this paper, we find for the case \(bQ>0.5\), the phase structure of the black hole is similar to that of the Reissner–Nordström–AdS black hole in the entropy–temperature plane. While for the case \(bQ<0.5\),Footnote 4 there is a novel phase structure, which has not been observed previously. Specially speaking, a new phase branch emerges so that there are two unstable regions and two phase transition temperature correspondingly. All these phase structures are probed by the non-local observables such as equal time two point correlation function as well as holographic entanglement entropy. For the dual conformal field, its volume is finite for the space time we investigated is asymptotically a global AdS black hole. Its temperature, which is dual to the Hawking temperature of the black hole, is also finite.

Our paper is outlined as follows. In the next section, we will review the thermodynamic properties of the Born–Infeld–anti-de Sitter black hole first, and then study its phase structure in T–S plane in a fixed charge ensemble. In Sect. 3, we will employ the equal time two point correlation function and holographic entanglement entropy to probe the phase structure of the Born–Infeld–anti-de Sitter black hole. In each subsection, Maxwell’s equal area law is checked and the critical exponent of the heat capacity is obtained. The last section is devoted to discussions and conclusions.

2 Thermodynamic phase transition of the Born–Infeld–anti-de Sitter black hole

2.1 Review of the Born–Infeld–anti-de Sitter black hole

The 4-dimensional Born–Infeld AdS black hole is a solution of the following action [53]:

in which \(F=\frac{1}{4}F_{\mu \nu }F^{\mu \nu }\), R is scalar curvature, G is the gravitational constant, \( \Lambda \) is the cosmological constant that relates to the AdS radius as \( \Lambda =-3/l^2\), and b is the Born–Infeld parameter. The solution of the Born–Infeld AdS black hole can be written as [54, 55]

where

in which the gravitational constant G and the light velocity c have been set to be 1, and \(_2F_1\) is the hypergeometric function. From Eq. (2.3), we know that in the limit \(b \rightarrow \infty \), \(Q\ne 0\), the solution reduces to the Reissner–Nordström–AdS black hole, and in the limit \(Q\rightarrow 0\), it reduces to the Schwarzschild AdS black hole.

The electrostatic potential difference between the black hole horizon and the infinity is

in which \(r_+\) is the event horizon of the black hole. The ADM mass of the black hole, defined by \(f(r_+) = 0\), is given by

With the help of Eq. (2.5), the Hawking temperature defined by \(T=\frac{f^{\prime }(r)}{4\pi }\mid _{r_+}\) can be written as

which is also the temperature of the conformal field theory from the viewpoint of AdS/CFT correspondence. In addition, according to the Bekenstein–Hawking entropy–area relation, we can get the black hole entropy

Inserting Eqs. (2.7) into (2.6), we can get the entropy–temperature relation, namely

It is obvious that besides the charge Q, the Born–Infeld parameter b also affects the phase structure of this space time in the T–S plane.

2.2 Phase transition of thermal entropy

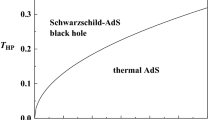

Based on Eq. (2.8), we will discuss the phase structure of the Born–Infeld–anti-de Sitter black hole. We are interested in how b or Q affects it. During the numeric process, the AdS radius l will set to be 1. For a fixed charge Q, the effect of b on the phase structure is shown in Fig. 1. It is obvious that, for small b, the phase structure resembles as that of the Schwarzschild AdS black hole, and for large b, it resembles as that of the Reissner–Nordström–AdS black hole as expected. From (b) of Fig. 1, we can see that as b increases, the minimum temperature of the space time decreases, and the entropy, also the event horizon, becomes smaller. The black hole thus can be formed easier. That is, the Born–Infeld parameter b promotes the formation of an AdS space time.

More interestingly, for the smaller charge, we find there is a novel phase transition, which is labeled by the red solid line in (a) of Fig. 1. From this curve, we know that there are two unstable regions. Namely the black hole will undergo the following transition: unstable–stable–unstable. Compared with that of the Reissner–Nordström–AdS black hole, a new phase branch emerges at the onset of the phase transition. The influence of the charge on the phase structure for a fixed Born–Infeld parameter is plotted in Fig. 2.

Apparently, the phase structure is similar to that of the Schwarzschild AdS black hole for the small charges, and Reissner–Nordström–AdS black hole for large charges. From (a) of Fig. 2, we observe that the larger the charge is, the lower the minimum temperature will be. In other words, the charge will promote the formation of an AdS space time, which has the same effect as that of the Born–Infeld parameter on the phase structure of the black hole.

For the case \(b=4\) in (b) of Fig. 2, we see that for some intermediate values of charge Q, there is also a similar phase structure as that in (b) in Fig. 1, which is labeled by the red solid line in (b) of Fig. 2. Note, however, that, for large b, the novel phase structure disappears, which is shown in Fig. 3. For in this case, the Born–Infeld parameter is large enough, so that the phase structure resembles completely that of the Reissner–Nordström–AdS black hole.

Next, we will study in detail the phase structure of the Born–Infeld AdS black hole for the case \(b=4\) and \(b=5\), respectively. To finish it, we should first find the critical charge for a fixed Born–Infeld parameter by the condition

However, from Eq. (2.6), we find it is hard to get the analytical result directly. Taking the case \(b=5\) as an example, we will show how to get it numerically next. We first plot a series of curves for different charges in the T–S plane, which is shown in (a) of Fig. 3, and we read off the charge which satisfies likely the condition \((\frac{\partial T}{\partial S})_Q=0\). With that rough value, we plot a bunch of curves in the T–S plane once with smaller step so that we can get the most likely value of charge. From (b) of Fig. 3, we find the critical charge should be \(0.168<Q_\mathrm{c}<0.17\), which are labeled by the red dashed lines in (b) of Fig. 3. Lastly, we adjust the value of \(Q_\mathrm{c}\) by hand to find the only solution \(S_\mathrm{c}\) that satisfies Eq. (2.9), which produces \(Q_\mathrm{c}=0.168678344129\), \(S_\mathrm{c}=0.510691\). Substituting these critical values into Eq. (2.6), we further get the critical temperature \(T_\mathrm{c}=0.259444\).

Relations between entropy and temperature for different Q at \(b=5\). The red solid line and dashed line in (a) correspond to the minimum temperature and Hawking–Page phase transition temperature. The red dashed lines from top to down in (b) correspond to the first order phase transition temperature and second order phase transition temperature. The blue solid line in (a) corresponds to \(Q=0\), and the blue solid lines in (b) correspond to \(Q=0.11, 0.168678344129, 0.21\)

Having obtained the critical charge, we can plot the isocharge curves for the case \(b=5\) in the T–S plane, which is shown in Fig. 4. We observe that the black hole undergoes a Hawking–Page phase transition and a Van der Waals-like phase transition. Specifically speaking, for the case \(Q=b=0\), there is a minimum temperature \(T_0=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2 \pi }\) [50], which is indicated by the red dashed line in (a) of Fig. 4. When the temperature is higher than \(T_0\), there are two additional black hole branches. The small branch is unstable while the large branch is stable. The Hawking–Page phase transition occurs at the temperature given by \(T_1=\frac{1}{\pi }\) [50], which indicated by the red dotted line. This phase transition is first order. We also can observe the Hawking–Page phase transition in the F–T plane, in which F is the Helmholtz free energy defined byFootnote 5

From (a) of Fig. 5, we know that there is a minimum temperature \(T_0\), and above this temperature, there are two branches. The lower branch is stable always. The Hawking–Page phase transition occurs at \(T_1\) for in this case the free energy vanishes.

For the case \(Q\ne 0\), the phase structure is similar to that of the Van der Waals phase transition, which is shown in (b) of Fig. 4. We can see that black holes endowed with different charges have different phase structures. For the small charge, there is an unstable black hole interpolating between the stable small hole and stable large hole.

The small stable hole will jump to the large stable hole at the critical temperature \(T_\mathrm{a}\). As the charge increases to the critical charge, the small hole and the large hole merge into one and squeeze out the unstable phase so that an inflection point emerges. The divergence of the heat capacity in this case implies that the phase transition is second order. As the charge exceeds the critical charge, we simply have one stable black hole at each temperature. The Van der Waals-like phase transition can also be observed from the F–T relation. From (b) of Fig. 5, we observe that there is a swallowtail structure, which corresponds to the unstable phase in the top curve in (b) Fig. 4. The critical temperature \(T_\mathrm{a}=0.2825\) is apparently the value of the horizontal coordinate of the junction between the small black hole and the large black hole. As the temperature is lower than the critical temperature \(T_\mathrm{a}\), the free energy of the small black hole is lowest, so the small hole is stable. As the temperature is higher than \(T_\mathrm{a}\), the free energy of the large black hole is lowest, so the large black hole dominates thereafter. The non-smoothness of the junction indicates that the phase transition is first order. From (c) of Fig. 5, we know that there is an inflection point, which corresponds to the inflection point in the middle curve in (b) of Fig. 4. The horizontal coordinate of the inflection point corresponds to the second order phase transition temperature \(T_\mathrm{c}\).

Relations between entropy and temperature for different Q at \(b=4\). The red solid line and dashed line in (a) correspond to pseudo phase transition temperature and first order phase transition temperature. The red dashed lines from top to down in (b) correspond to the first order phase transition temperature and second order phase transition temperature. The blue solid line in (a) corresponds to \(Q=0.115\), and the blue solid lines in (b) correspond to \(Q=0.13, 0.16987452395, 0.21\)

Similarly, we also can study the phase structure for the case \(b=4\) in the T–S plane. To finish it, we should first find the critical charge. Adopting the same strategy as that of the case \(b=5\), we find \(Q_\mathrm{c} = 0.16987452395\), \(S_\mathrm{c} = 0.502683752119928\), \(T_\mathrm{c} =0.259166\). For the case \(Q=0\), the phase structure is the same as that in (a) of Fig. 4. We will not repeat it here. For the case \(Q\ne 0\), we find besides the Van der Waals-like phase transition, there is a novel phase transition for \(Q=0.115\) as observed in Figs. 1 and 2,Footnote 6 which is plotted in (a) of Fig. 6. That is, at the beginning of the phase transition, there is a new black hole branch, which is unstable and its life is very short so that it becomes to a small stable black hole quickly. In addition, we find there are two unstable region, and correspondingly in the F–T plane, we observe two swallowtail structures, which is shown in (a) of Fig. 7. The horizontal coordinate of the junction of the swallowtail corresponds to the phase transition temperature, thus besides the first order phase transition temperature between the small black hole and large black hole, labeled by \(T_2\), there is a new phase transition temperature, labeled by \(T_3\). It should be stressed that the new phase transition cannot take place actually, for above the critical temperature \(T_2\), the free energy of the large black hole is lowest so that the space time is dominated by the large black hole, which can be seen in (a) of Fig. 7. Thus, we call thus phase transition pseudo phase transition.

We observe that there is also a Van der Waals-like phase transition, which is plotted in (b) of Fig. 6. The first order phase transition temperature \( T_\mathrm{a}\) can be read off from the horizontal coordinate of the junction of the swallowtail structure in (b) of Fig. 7, and the second order phase transition temperature \( T_\mathrm{c}\) can be read off from the horizontal coordinate of the inflection point in (c) of Fig. 7.

As done in [42], we will also check numerically whether Maxwell’s equal area law holds for the first order phase transition and pseudo phase transition, which states

in which T(S, Q) is defined in Eq. (2.8), \(T_\mathrm{x}\) is the phase transition temperature, and \(S_{\mathrm{min}}\), \(S_{\mathrm{max}}\) are the smallest and the largest values of unstable region which satisfies the equation \(T(S,Q)=T_\mathrm{x}\). Usually for this equation, there are three roots \(S_1,S_2,S_3\), so \(S_{\mathrm{min}}=S_1\), \(S_{\mathrm{max}}=S_3\), \(T_\mathrm{x}=T_\mathrm{a}\). But for the case \(b=4,Q=0.115\), there are four roots. One can see from (a) of Fig. 6 that \(S_{\mathrm{min}}=S_1\), \(S_{\mathrm{max}}=S_3\) for the pseudo phase transition with phase transition temperature \(T_\mathrm{x}=T_3\), and \(S_{\mathrm{min}}=S_2\), \(S_{\mathrm{max}}=S_4\) for the first order phase transition with phase transition temperature \(T_\mathrm{x}=T_2\). The calculated results for the first order phase transition and pseudo phase transition are listed in Table 1.

Isocharges in the \(\delta L\)–T plane for the case \(b=5, \theta _0=0.2\). The red solid line and dashed line in (a) correspond to the minimum temperature and Hawking–Page phase transition temperature. The red solid lines from top to down in (b) correspond to the first order phase transition temperature and second order phase transition temperature. The blue solid line in (a) corresponds to \(Q=0\), and the blue solid lines in (b) correspond to \(Q=0.11, 0.168678344129, 0.21\)

Isocharges in the \(\delta L\)–T plane for the case \(b=5, \theta _0=0.3\). The red solid line and dashed line in (a) correspond to the minimum temperature and Hawking–Page phase transition temperature. The red solid lines from top to down in (b) correspond to the first order phase transition temperature and second order phase transition temperature. The blue solid line in (a) corresponds to \(Q=0\), and the blue solid lines in (b) correspond to \(Q=0.11, 0.168678344129, 0.21\)

From this table, we can see that \(A_\mathrm{L}\) equals \(A_\mathrm{R}\) for different b in our numeric accuracy. The equal area law therefore holds.

For the second order phase transition, we know that the heat capacity is divergent near the critical point and the critical exponent is \(-2/3\). As stated in [40], near the critical point, there is always a linear relation

with 3 the slope. It is not difficult to show that, for the case \(b=4,5\) in our gravity model, the temperature and entropy also satisfy this linear relation near the critical point. Next, we will take Eq. (2.12) as a reference to check whether there is a similar relation for the second order phase transition in the two point correlation function-temperature plane as well as entanglement entropy–temperature plane.

3 Phase transition in the framework of holography

Having obtained the phase structure of thermal entropy of the Born–Infeld AdS black hole in the T–S plane, we will study the phase structure of two point correlation function and entanglement entropy in the fled theory to see whether they have similar phase structures and critical behaviors.

3.1 Phase structure probed by two point correlation function

According to the AdS/CFT correspondence, in the large \(\Delta \) limit, the equal time two point correlation function for a scalar operator can be written as [56]

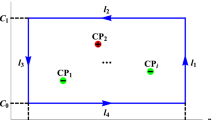

where \(\Delta \) is the conformal dimension of scalar operator \(\mathcal {O}\) in the dual field theory, L is the length of the bulk geodesic between the points \((t_0, x_i)\) and \((t_0, x_j)\) on the AdS boundary. In our gravity model, we can simply choose \((\phi =\frac{\pi }{2},\theta =0)\) and \((\phi =\frac{\pi }{2},\theta =\theta _0)\) as the two boundary points. Then with \(\theta \) to parameterize the trajectory, the proper length is given by

in which \(\dot{r}=\mathrm{d}r/ \mathrm{d}\theta \). Imagining \(\theta \) as time, and treating \(\mathcal {L}\) as the Lagrangian, one can get the equation of motion for \(r(\theta )\) by making use of the Euler–Lagrange equation. Then with the following boundary conditions

we can get the numeric result of \(r(\theta )\). To explore whether the size of the boundary region affects the phase structure, we will choose \(\theta _0=0.2, 0.3\) as two examples. Note that, for a fixed \(\theta _0\), the geodesic length is divergent, so it should be regularized by subtracting off the geodesic length in pure AdS with the same boundary region, denoted by \(L_0\).Footnote 7 To achieve this, we are required to set a UV cutoff for each case, which is chosen to be r(0.199) and r(0.299), respectively, for our two examples. The regularized geodesic length is labeled \(\delta L\equiv L-L_0\).

Isocharges in the \(\delta L\)–T plane for the case \(b=4, \theta _0=0.2\). The red solid line and dashed line in (a) correspond to the minimum temperature and Hawking–Page phase transition temperature. The red solid lines from above to down in (b) correspond to the first order phase transition temperature and second order phase transition temperature. The blue solid line in (a) corresponds to \(Q=0.115\), and the blue solid lines in (b) correspond to \(Q=0.13, 0.16987452395, 0.21\)

Isocharges in the \(\delta L\)–T plane for the case \(b=4, \theta _0=0.3\). The red solid line and dashed line in (a) correspond to the minimum temperature and Hawking–Page phase transition temperature. The red solid lines from top to down in (b) correspond to the first order phase transition temperature and second order phase transition temperature. The solid blue line in (a) corresponds to \(Q=0.115\), and the solid bile lines in (b) correspond to \(Q=0.13, 0.16987452395, 0.21\)

We plot the relation between T and \(\delta L\) for the case \(b=5\) in Figs. 8 and 9. From these figures, one can see that \(\delta L\) demonstrates a similar phase structure as that of the thermal entropy in Fig. 4. Namely the two point correlation function can probe both the Hawking–Page phase transition and the Van der Waals-like phase transition. Precisely speaking, we find that the minimum temperature \(T_0\) as well as Hawking–Page phase transition temperature \(T_1\) in (a), the first order phase transition temperature \(T_{\mathrm{a}}\), and second order phase transition temperature \(T_\mathrm{c}\) in (b) are exactly the same as those in T–S plane. This conclusion does not change as \(\theta _0\) varies in a reasonable region, which can be seen from Figs. 8 and 9.

With the two point correlation function, we also can probe the phase structure of the case \(b=4\), which is shown in Figs. 10 and 11. As the case as the thermal entropy in the T–S plane, we find there ia also a novel phase structure besides the Van der Waals-like phase transition in the \(\delta L-T\) plane. There are also two unstable region, correspondingly two phase transition temperature, labeled by \(T_2\), \(T_3\). For the phase transition temperature mentioned above, it is easy to check \(T_0\) by locating the position of local minimum. But in order to locate \(T_2\), \(T_3\), and \(T_{\mathrm{a}}\) precisely, we are required to examine the equal area law for the first order phase transition as well as pseudo phase transition. And to locate \(T_\mathrm{c}\), we should obtain the critical exponent \(-2/3\) for the second order phase transition, which are documented as follows.

In the \(\delta L\)–T plane, we define the equal area law as

in which \(T(\delta L)\) is an interpolating function obtained from the numeric result, \(T_{\mathrm{x}} \) is the phase transition temperature, and \(\delta L_{\mathrm{min}}\), \(\delta L_{\mathrm{max}}\) are the smallest and largest values of the unstable region which satisfy the equation \(T(\delta L)=T_{\mathrm{x}}\). Similar to the equal area law in the \(S-T\) plane, we know that, for \(b=5,Q=0.11\), and \(b=4,Q=0.13\), and \(T_{\mathrm{x}}=T_{\mathrm{a}}\), while for \(b=4,Q=0.115\), \(T_{\mathrm{x}}=T_{2}\) for the first order phase transition and \(T_{\mathrm{x}}=T_{3}\) for the pseudo phase transition. For different b and \(\theta _0\), the calculated results are listed in Table 2.

It is obvious that \(A_\mathrm{L}\) equals \(A_\mathrm{R}\) for different b and \(\theta _0\) in a reasonable accuracy. That is, in the \(T-\delta L\) plane, the equal area law holds, and it is independent of the Born–Infeld parameter as well as the size of the boundary region.

In order to get the critical exponent for the second order phase transition in the \(T-\delta L\) plane, we should first define an analogous heat capacity

Provided a similar relation as showed in Eq. (2.12) is satisfied, one can get the critical exponent immediately. So next, we are interested in the logarithm of the quantities \(T-T_\mathrm{c}\), \(\delta L-\delta L_\mathrm{c}\), in which \(T_\mathrm{c}\) is the critical temperature mentioned previously, and \(L_\mathrm{c}\) is obtained numerically by the equation \(T(\delta L)=T_\mathrm{c}\). We plot the relation between \( \log \mid T -T_\mathrm{c}\mid \) and \(\log \mid \delta L-\delta L_\mathrm{c}\mid \) for different \(\theta _0\) and b in Fig. 12, where these straight lines can be fitted as

It is obvious that the slope is about 3, which indicates that the critical exponent is \(-2/3\) nearly for the analogous heat capacity, and the phase transition is also second order with the phase transition temperature \(T_\mathrm{c}\).

3.2 Phase structure probed by holographic entanglement entropy

For a given quantum field theory described by a density matrix \(\rho \), the entanglement entropy for a region A and its complement B is defined as

where \(\rho _\mathrm{A}=\mathrm{Tr}_\mathrm{B}(\rho )\) is the reduced density matrix. From the viewpoint of holography, [59, 60] gave a very simple geometric description for computing \(S_\mathrm{A}\) for static states in terms of the area of a bulk minimal surface anchored on \(\partial A\), which states that

where \(\gamma \) is the codimension-2 minimal surface with boundary condition \(\partial \gamma =\partial A\). We will take the region \(\gamma \) to be a spherical cap on the boundary delimited by \(\theta \le \theta _0\).Footnote 8 Then based on the definition of area and (2.2), (3.8) can be rewritten as

in which \(r^{\prime }=\mathrm{d}r/ \mathrm{d}\theta \). Making use of the Euler–Lagrange equation, one can get the equation of motion of \(r(\theta )\). With the boundary conditions in Eq. (3.3), we can obtain the numeric result of \(r(\theta )\) immediately. Note that the entanglement entropy is divergent at the boundary, so it should be regularized by subtracting off the entanglement entropy in pure AdS with the same entangling surface and boundary values. We label the regularized entanglement entropy as \(\delta S\). We choose the size of the boundary region as \(\theta _0=0.2\) and set the UV cutoff in the dual field theory to be r(0.199).

The isocharges for the cases \(b=5\) and \(b=4\) are plotted in Figs. 13 and 14. From Fig. 13, we know that the entanglement entropy exhibits a Hawking–Page phase transition, and a Van der Waals-like phase transition as the charge increases from 0 to 0.21. For the case \(b=4\), the entanglement entropy also exhibits the novel phase structure besides the Van der Waals-like phase transition as that of the thermal entropy as well as two point correlation function, which is shown in (a) of Fig. 14.

Isocharges in the \(\delta S\)–T plane for the case \(b=5, \theta _0=0.2\). The red solid line and dashed line in (a) correspond to the minimum temperature and Hawking–Page phase transition temperature. The red solid lines from top to down in (b) correspond to the first order phase transition temperature and second order phase transition temperature. The blue solid line in (a) corresponds to \(Q=0\), and the blue solid lines in (b) correspond to \(Q=0.11, 0.168678344129, 0.21\)

Isocharges in the \(\delta S\)–T plane for the case \(b=4, \theta _0=0.2\). The red solid line and dashed line in (a) correspond to the minimum temperature and Hawking–Page phase transition temperature. The red solid lines from above to down in (b) correspond to the first order phase transition temperature and second order phase transition temperature. The blue solid line in (a) corresponds to \(Q=0.115\), and the blue solid lines in (b) correspond to \(Q=0.13, 0.16987452395, 0.21\)

We will also employ Maxwell’s equal area law to locate the first order phase transition temperature, namely \(T_\mathrm{a}\) in (b) of Figs. 13 and 14, \(T_2\) in (a) of Fig. 14, and pseudo phase transition temperature \(T_3\) in (a) of Fig. 14. In the \(\delta S\)–T plane, we define the equal area law as

in which \(T(\delta S)\) is an interpolating function obtained from the numeric result, and \(\delta S_{\mathrm{min}}\), \(\delta S_{\mathrm{max}}\) are the smallest and largest roots of the unstable regions, which satisfy the equation \(T(\delta S)=T_{\mathrm{x}}\). Surely the values of the phase transition temperature \( T_{\mathrm{x}} \) depends on the choice of Q and b. For different Q and b, the results of \(\delta S_{\mathrm{min}}\), \(\delta S_{\mathrm{max}}\) and \(A_\mathrm{L}\), \(A_\mathrm{R}\) are listed in Table 3.

It is obvious that \(A_\mathrm{L}\) equals nearly \(A_\mathrm{R}\) for a fixed Q and b. That is, the equal area law is also valid for the first order phase transition and pseudo phase transition in the entanglement entropy–temperature plane. This result is the same as that of the thermal entropy as well as two point correlation function.

To confirm that \(T_\mathrm{c}\) is the second order phase transition temperature in the \(\delta S\)–T plane, we should explore whether it satisfies a similar relation to Eq. (2.12). For different b and Q, the relation between \( \log \mid T-T_\mathrm{c}\mid \) and \(\log \mid \delta S-\delta S_\mathrm{c}\mid \) are plotted in Fig. 15, in which \(S_\mathrm{c}\) is the critical entropy obtained numerically by the equation \(T(\delta S)=T_\mathrm{c}\). The analytical result of these curves can be fitted as

We find for a fixed b and Q, the slope is always about 3, which is consistent with that of the thermal entropy. That is, the entanglement entropy also exhibits a second order phase transition, with phase transition temperature \(T_\mathrm{c}\), as that of the thermal entropy and two point correlation function.

4 Concluding remarks

Investigation on the phase structure of a back hole is of great importance for it reveals whether and how a black hole emerges. Usually, it is realized by studying the relation between some thermodynamic quantities in a fixed ensemble. In this paper, we found that the phase structure of a back hole also can be probed by the two point correlation function and holographic entanglement entropy, which provides a new strategy to understand the phase structure of the black holes from the viewpoint of holography.

Specially speaking, we first investigated the phase structure of the Born–Infeld–anti-de Sitter black holes in the T–S plane in the fixed charge ensemble. We found that the phase structure of the black hole depends on not only the value of Q or b, but also the combination of bQ. For the case \(b=5\), the black hole resembles as the Reissner–Nordström–AdS black hole, and it undergoes the Van der Waals-like phase transition as its charge satisfies the non-extremal condition \(bQ>0.5\). For the case \(b=4\), besides the Van der Waals-like phase transition, we also observed a novel phase structure for the case \(bQ<0.5\). With the two point correlation function and holographic entanglement entropy, we further probed the phase structure of the Born–Infeld–anti-de Sitter black holes and found that both the probes exhibited the same phase structure as that of the thermal entropy for cases \(bQ>0.5\) and \(bQ<0.5\) regardless of the size of the boundary region. This conclusion was reinforced by checking the equal area law for the first order phase transition as well as pseudo phase transition, and calculating the critical exponent of the analogous heat capacity for the second order phase transition.

In previous investigation on the phase structure of the Born–Infeld–anti-de Sitter black holes, authors concentrated mainly on that of \(bQ>0.5\) [46–50]. In this paper we found that the phase structure for the case \(bQ<0.5\) is also interesting. As \(bQ\ll 0.5\), the black hole resembles as the Schwarzschild AdS black hole as expected, and there is a minimum temperature. We found the larger the charge or the Born–Infeld parameter is, the smaller the minimum temperature will be. That is, both the charge and the Born–Infeld parameter promote the formation of an AdS black hole. As bQ approaches to 0.5, a new extremal small black hole branch emerges compared with that of the Reissner–Nordström–AdS black hole, so that there are two unstable regions and correspondingly two phase transition temperature. The high temperature phase transition was found to be pseudo for in this case the space time was dominated by the large black hole, which was observed from the F–T relation.

Comparing Figs. 8 and 10 with Figs. 13 and 14, respectively, we find they are the same besides the horizontal coordinate. Both the holographic entanglement entropy and the two point correlation function thus are good probes. In fact this behavior can be understood by comparing their dual physical quantities in the bulk. According to the AdS/CFT correspondence, the two point correlation function is dual to the length of the geodesic, and the entanglement entropy is dual to the area of the minimal surface, which is the product of the length of the geodesic and the lengths of the other covariant coordinates on the minimal surface. The covariant coordinates do not affect the dynamics of the minimal surface though they contribute to the area. So it is not suspect that the geodesic and minimal surface have the same dynamics so that both the two point correlation function and the holographic entanglement entropy can probe the phase structure of the black holes.

Notes

This is the so-called extended phase space.

In fact, the Van der Waals phase transition has also been observed for a zero temperature system in the framework of holography [41].

The equal area law was introduced by Maxwell in order to explain the experimental behavior of a real fluid. Theoretically, it can be derived from the variation of the Gibbs free energy G: \(\mathrm{d}G=V\mathrm{d}P-S\mathrm{d}T\). At constant P, one can get Maxwell’s area law in the T–S plane: \(T_{\star } \Delta S_{1,2}=\int _1^2 T \mathrm{d}S.\)

For the case \(bQ < 0.5\), there is also a black hole, but the charge or the Born–Infeld parameter of the black hole is small so that the extreme black hole has not been formed.

Note that here we have implicitly chosen the pure AdS as the reference spacetime because the free energy vanishes for pure AdS by this formula.

This phase transition can happen also for other values of Q, and \(Q=0.115\) is our numeric choice here.

References

J.M. Maldacena, Large N limit of superconformal field theories and supergravity. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 38, 1113 (1999)

E. Witten, Anti-de Sitter space and holography. Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 2, 253 (1998). arXiv:hep-th/9802150

S.S. Gubser, I.R. Klebanov, A.M. Polyakov, Gauge theory correlators from noncritical string theory. Phys. Lett. B 428, 105 (1998). arXiv:hep-th/9802109

V. Balasubramanian et al., Thermalization of strongly coupled field theories. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 191601 (2011). arXiv:1012.4753 [hep-th]

V. Balasubramanian et al., Holographic thermalization. Phys. Rev. D 84, 026010 (2011). arXiv:1103.2683 [hep-th]

D. Galante, M. Schvellinger, Thermalization with a chemical potential from AdS spaces. JHEP 1207, 096 (2012). arXiv:1205.1548 [hep-th]

E. Caceres, A. Kundu, Holographic thermalization with chemical potential. JHEP 1209, 055 (2012). arXiv:1205.2354 [hep-th]

X.X. Zeng, B.W. Liu, Holographic thermalization in Gauss–Bonnet gravity. Phys. Lett. B 726, 481 (2013). arXiv:1305.4841 [hep-th]

X.X. Zeng, X.M. Liu, B.W. Liu, Holographic thermalization with a chemical potential in Gauss–Bonnet gravity. JHEP 03, 031 (2014). arXiv:1311.0718 [hep-th]

X.X. Zeng, D.Y. Chen, L.F. Li, Holographic thermalization and gravitational collapse in the spacetime dominated by quintessence dark energy. Phys. Rev. D 91, 046005 (2015). arXiv:1408.6632 [hep-th]

H. Liu, S.J. Suh, Entanglement tsunami: universal scaling in holographic thermalization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 011601 (2014). arXiv:1305.7244 [hep-th]

S.J. Zhang, E. Abdalla, Holographic thermalization in charged dilaton anti-de sitter spacetime. Nucl. Phys. B 896, 569 (2015). arXiv:1503.07700 [hep-th]

A. Buchel, R.C. Myers, A.V. Niekerk, Nonlocal probes of thermalization in holographic quenches with spectral methods. JHEP 02, 017 (2015). arXiv:1410.6201 [hep-th]

B. Craps et al., Gravitational collapse and thermalization in the hard wall model. JHEP 02, 120 (2014). arXiv:1311.7560 [hep-th]

G. Camilo, B. Cuadros-Melgar, E. Abdalla, Holographic thermalization with a chemical potential from Born–Infeld electrodynamics. JHEP 02, 103 (2015). arXiv:1412.3878 [hep-th]

T. Albash, C.V. Johnson, Holographic studies of entanglement entropy in superconductors. JHEP 1205, 079 (2012). arXiv:1202.2605 [hep-th]

R.G. Cai, S. He, L. Li, Y.L. Zhang, Holographic entanglement entropy in insulator/superconductor transition. JHEP 1207, 088 (2012). arXiv:1203.6620 [hep-th]

R.G. Cai, L. Li, L.F. Li, R.K. Su, Entanglement entropy in holographic P-wave superconductor/insulator model. JHEP 1306, 063 (2013). arXiv:1303.4828 [hep-th]

L.F. Li, R.G. Cai, L. Li, C. Shen, Entanglement entropy in a holographic p-wave superconductor model. Nucl. Phys. B 894, 15–28 (2015). arXiv:1310.6239 [hep-th]

R.G. Cai, L. Li, L.F. Li, R.Q. Yang, Introduction to holographic superconductor models. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 58, 060401 (2015). arXiv:1502.00437 [hep-th]

X. Bai, B.H. Lee, L. Li, J.R. Sun, H.Q. Zhang, Time evolution of entanglement entropy in quenched holographic superconductors. JHEP 040, 66 (2015). arXiv:1412.5500 [hep-th]

R.G. Cai, L. Li, L.F. Li, R.Q. Yang, Introduction to holographic superconductor models. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 58, 060401 (2015). arXiv:1502.00437 [hep-th]

Y. Ling, P. Liu, C. Niu, J. P. Wu, Z. Y. Xian, Holographic entanglement entropy close to quantum phase transitions. arXiv:1502.03661 [hep-th]

N. Engelhardt, T. Hertog, G.T. Horowitz, Holographic signatures of cosmological singularities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 121602 (2014). arXiv:1404.2309 [hep-th]

N. Engelhardt, T. Hertog, G.T. Horowitz, Further holographic investigations of big bang singularities. JHEP 1507, 044 (2015). arXiv:1503.08838 [hep-th]

S.W. Hawking, D.N. Page, Thermodynamics of black holes in anti-de sitter space. Commun. Math. Phys. 87, 577 (1983)

E. Witten, Anti-de Sitter space, thermal phase transition, and confinement in gauge theories. Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 2, 505 (1998). arXiv:hep-th/9803131

A. Chamblin, R. Emparan, C.V. Johnson, R.C. Myers, Charged AdS black holes and catastrophic holography. Phys. Rev. D 60, 064018 (1999). arXiv:hep-th/9902170

R.G. Cai, Gauss–Bonnet black holes in AdS spaces. Phys. Rev. D 65, 084014 (2002). arXiv:hep-th/0109133

C. Niu, Y. Tian, X.N. Wu, Critical phenomena and thermodynamic geometry of RN-AdS black holes. Phys. Rev. D 85, 024017 (2012). arXiv:1104.3066 [hep-th]

D. Kastor, S. Ray, J. Traschen, Enthalpy and the mechanics of AdS black holes. Class. Quant. Grav. 26, 195011 (2009). arXiv:0904.2765 [hep-th]

D. Kubiznak, R.B. Mann, P-V criticality of charged AdS black holes. JHEP 1207, 033 (2012). arXiv:1205.0559 [hep-th]

J. Xu, L. M. Cao, Y.P. Hu, P-V criticality in the extended phase space of black holes in massive gravity. Phys. Rev. D 91, 124033 (2015). arXiv:1506.03578 [gr-qc]

R.G. Cai, L.M. Cao, L. Li, R.Q. Yang, P-V criticality in the extended phase space of Gauss–Bonnet black holes in AdS space. JHEP 09, 005 (2013). arXiv:1306.6233 [gr-qc]

S.H. Hendi, A. Sheykhi, S. Panahiyan, B. Eslam Panah, Phase transition and thermodynamic geometry of Einstein-Maxwell-dilaton black holes. Phys. Rev. D 92, 064028 (2015). arXiv:1509.08593 [hep-th]

R.A. Hennigar, W.G. Brenna, R.B. Mann, P-V criticality in quasitopological gravity. JHEP 1507, 077 (2015). arXiv:1505.05517 [hep-th]

S.W. Wei, Y.X. Liu, Clapeyron equations and fitting formula of the coexistence curve in the extended phase space of charged AdS black holes. Phys. Rev. D 91, 044018 (2015). arXiv:1411.5749 [hep-th]

J.X. Mo, W.B. Liu, P-V criticality of topological black holes in Lovelock-Born–Infeld gravity. Eur. Phys. J. C 74, 2836 (2014). arXiv:1401.0785 [hep-th]

E. Spallucci, A. Smailagic, Maxwell’s equal area law for charged Anti-deSitter black holes. Phys. Lett. B 723, 436 (2013). arXiv:1305.3379 [hep-th]

C.V. Johnson, Large N phase transitions, finite volume, and entanglement entropy. JHEP 1403, 047 (2014). arXiv:1306.4955 [hep-th]

F. Bigazzi, A.L. Cotrone, C. Nunez, A. Paredes, Heavy quark potential with dynamical flavors: a first order transition. Phys. Rev. D 78, 114012 (2008). arXiv:0806.1741 [hep-th]

P.H. Nguyen, An equal area law for the van der Waals transition of holographic entanglement entropy. JHEP 12, 139 (2015). arXiv:1508.01955 [hep-th]

E. Caceres, P.H. Nguyen, J.F. Pedraza, Holographic entanglement entropy and the extended phase structure of STU black holes. JHEP 1509, 184 (2015). arXiv:1507.06069 [hep-th]

X.X. Zeng, H. Zhang, L.F. Li, Phase transition of holographic entanglement entropy in massive gravity. arXiv:1511.00383 [gr-qc]

A. Dey, S. Mahapatra, T. Sarkar, Thermodynamics and entanglement entropy with Weyl corrections. arXiv:1512.07117 [hep-th]

Y.S. Myung, Y.W. Kim, Y.J. Park, Thermodynamics and phase transitions in the Born–Infeld–anti-de Sitter black holes. Phys. Rev. D 78, 084002 (2008). arXiv:0805.0187 [gr-qc]

A. Lala, D. Roychowdhur, Ehrenfests scheme and thermodynamic geometry in Born–Infeld AdS black holes. Phys. Rev. D 86, 084027 (2012). arXiv:1111.5991 [gr-qc]

S.H. Hendi, S. Panahiyan, Thermodynamic instability of topological black holes in Gauss–Bonnet gravity with a generalized electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. D 90, 124008 (2014). arXiv:1501.05481 [gr-qc]

D.C. Zou, S.J. Zhang, B. Wang, Critical behavior of Born–Infeld AdS black holes in the extended phase space thermodynamics. Phys. Rev. D 89, 044002 (2014). arXiv:1311.7299 [hep-th]

R. Banerjee, D. Roychowdhury, Critical phenomena in Born–Infeld AdS black holes. Phys. Rev. D 85, 044040 (2012). arXiv:1111.0147 [gr-qc]

R. Banerjee, D. Roychowdhury, Thermodynamics of phase transition in higher dimensional AdS black holes. JHEP 11, 004 (2011). arXiv:1109.2433 [gr-qc]

Sharmanthie Fernando, Thermodynamics of Born–Infeld–anti-de Sitter black holes in the grand canonical ensemble. Phys. Rev. D 74, 104032 (2006). arXiv:hep-th/0608040

D.A. Rasheed, Non-linear electrodynamics: zeroth and first laws of black hole mechanics. arXiv:hep-th/9702087

R.G. Cai, D.W. Pang, A. Wang, Born–Infeld black holes in (A)dS spaces. Phys. Rev. D 70, 124034 (2004). arXiv:hep-th/0410158

T.K. Dey, Born–Infeld black holes in the presence of a cosmological constant. Phys. Lett. B 595, 484 (2004). arXiv:hep-th/0406169

V. Balasubramanian, S.F. Ross, Holographic particle detection. Phys. Rev. D 61, 044007 (2000). arXiv:hep-th/9906226

D.D. Blanco, H. Casini, L.-Y. Hung, R.C. Myers, Entropy and holography. JHEP 08, 060 (2013). arXiv:1305.3182 [hep-th]

H. Casini, M. Huerta, R.C. Myers, A derivation of holographic entanglement entropy. JHEP 1105, 036 (2011). arXiv:1102.0440 [hep-th]

S. Ryu, T. Takayanagi, Holographic derivation of entanglement entropy from AdS/CFT. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 181602 (2006). arXiv:hep-th/0603001

S. Ryu, T. Takayanagi, Aspects of holographic entanglement entropy. JHEP 0608, 045 (2006). arXiv:hep-th/0605073

V.E. Hubeny, H. Maxfield, M. Rangamani, E. Tonni, Holographic entanglement plateaux. JHEP 08, 092 (2013). arXiv:1306.4004 [hep-th]

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor Rong-Gen Cai for his helpful suggestions. This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 11365008, 11205226, 11575270), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2016M590138), Natural Science Foundation of Education Committee of Chongqing (Grant No. KJ1500530), Basic Research Project of Science and Technology Committee of Chongqing (Grant No. cstc2016jcyja0364), and Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (Grant No. 2014CFB608).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Funded by SCOAP3

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng, XX., Liu, XM. & Li, LF. Phase structure of the Born–Infeld–anti-de Sitter black holes probed by non-local observables. Eur. Phys. J. C 76, 616 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-016-4463-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-016-4463-4