Abstract

The world’s population is aging, and intergenerational conflicts between older adults and young people are becoming more serious. This study focused on ageism as a cause of intergenerational conflicts and older adults’ diminished mental health status. We conducted an online survey of older Japanese participants (n = 1.096). Our results indicated that older adults who perceived more ageism directed toward them (1) had more negative attitudes toward young people and (2) had lower life satisfaction, which persisted even after controlling for variables such as old age identity and depressive tendencies. Accordingly, we suggest that ageism may reinforce intergenerational conflicts between older adults and young people and compromise older adults’ mental health status. The findings of this study can aid gerontological and psychological research aimed at reducing ageism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

The world’s population is aging significantly, with the percentage of people 65 and older expected to reach 17.8% by 2060 [24]. This trend is remarkably pronounced in Japan, where 29.1% of the total population in 2021 is aged 65 or older [7]. In this aging society, intergenerational conflicts between older adults and young people have become more serious [9] and are frequently seen in a wide range of workplaces [25, 27] and nursing care cases [21]. Moreover, such intergenerational conflicts often prevent older adults from participating in society in a mentally healthy state [22] and playing an active role as a valuable social resource. Therefore, it is essential to investigate how the conflicts arise and are reinforced. Meanwhile, in this study, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) definition, older adults are defined as people over 64 years of age.

This study focuses on ageism (i.e., the process of systematically discriminating against older adults based on their age [2]) as a cause of intergenerational conflicts and lower mental health status of older adults. The research agenda of the Decade of Healthy Ageing 2020–2030, a major initiative by the WHO, discusses the negative effects of ageism on older adults [26]. Specifically, we conducted an online survey of Japanese participants aged 65 and older. We found that those who perceived more ageism (i.e., the degree to which they perceive ageism in general) have more negative attitudes toward young people and less life satisfaction (i.e., satisfaction with their daily lives). We also investigate whether these relationships are still pronounced even after controlling for variables such as old age identity (i.e., the degree to which people feel they belong to the social group of older adults) and depressive tendency. With the outbreak of COVID-19, intergenerational conflicts such as “older adults who are at high risk of severe cases vs. young people who are forced to refrain” have been apparent worldwide [20], including in Japan [21]. Considering societal changes following the COVID-19 pandemic, a detailed examination of the relationships between older adults’ perceived ageism and (1) their attitudes toward young people and (2) life satisfaction would be meaningful for future gerontological and psychological research. In addition, it will support our belief in the importance of reducing ageism. In the following, we review previous research on the effects of perceived ageism on older people.

Older Adults’ Perceived Ageism and Attitudes toward Young People

Most of the previous research on ageism has focused on the negative attitudes that young people have toward older adults [11]. On the contrary, empirical research on older adults’ attitudes toward young people remains scarce [14, 21], with most studies occurring within limited contexts such as the workplace. However, it has been shown that older adults are likely to hold negative attitudes toward young people in the workplace [6]. Considering this situation, we should focus on older adults’ perceived ageism in more general cases and examine its effect on their attitudes toward young people. Classification of and discrimination against individuals based on age is prevalent worldwide [5]. People are also likely to hold negative attitudes toward the target if they feel that the target directed negative attitudes toward them [16]. Accordingly, older adults who perceive more ageism toward them will have more negative attitudes toward young people. Such negative attitudes held by older adults in general situations are worth considering, as the attitudes may ultimately reinforce intergenerational conflicts.

Older Adults’ Perceived Ageism and Life Satisfaction

Many studies report that young people’s negative attitudes toward older adults adversely affect the latter’s physical and mental health [5, 13]. In addition, across the lifespan, people generally internalize negative old-age stereotypes. This process eventually has various deleterious effects [10, 17, 18]. Specifically, older adults who strongly internalize negative old-age stereotypes are more likely to feel stressed and lonely [12] and perform poorly on cognitive tasks [3]. These undesirable effects would also strongly affect life satisfaction in general. Accordingly, older adults with more perceived ageism toward them will have lower life satisfaction. We should focus on older adults’ life satisfaction because a decline in the satisfaction can lead to a curtailment of their social participation in various settings [22].

Overview and Hypotheses

This study conducts an online survey of older Japanese participants and investigates the relationships between perceived ageism and (1) negative attitudes toward young people and (2) life satisfaction. Individual variables potentially related to these associations include old age identity and depressive tendency. For example, those with a high old age identity are likely to view young people as an outgroup [15] and to hold negative attitudes toward young people. In addition, depressive tendency and life satisfaction in older adults are closely related [4]. We test the following hypotheses based on the above by controlling for the participants’ difference variables, including old age identity and depressive tendencies.

— Hypothesis 1: Older adults who perceive more ageism directed toward them have more negative attitudes toward young people.

— Hypothesis 2: Older adults who perceive more ageism directed toward them have diminished life satisfaction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants were recruited through Intage Inc., a major Japanese research company. Participants were 1096 Japanese older adults (65–98 years old); 546 were male, and 550 were female. The mean age of the participants was 70.45 years (SD = 4.58). This study was approved by the Ethical Committee at the University of Tokyo and was conducted in February 2022.

Measurements

Perceived ageism was measured using four items (seven-point Likert scale), including “The world is a place where the opinions and ideas of older adults are often ignored.” Mean scores were calculated (α = 0.78), and higher scores indicated more perceived ageism.

Attitudes toward young people were measured using seven items (seven-point Likert scale) [6], including “Personally, I do not want to spend a lot of time with young people.” Mean scores were calculated (α = 0.79), and higher scores indicated more negative attitudes.

Life satisfaction was measured using a single item [6], “Overall, I am satisfied with my life.” Participants rated responses on a seven-point Likert scale, and higher scores indicated more life satisfaction.

Old age identity was measured using seven items (seven-point Likert scale) [23], including “I feel good if I am described as a typical person of older adults.” Mean scores were calculated (α = 0.80), and higher scores indicated more old age identity.

Depressive tendencies were measured using six items (five-point Likert scale) [8], including “During the last 30 days, about how often did you feel nervous?” Mean scores were calculated (α = 0.88), and higher scores indicated more depressive tendencies.

Demographic information, including subjective wealth, cohabitation, work status, age, and gender, was also collected. Subjective wealth was measured using a single item, “How do you feel about your current financial situation?” Participants rated responses on a seven-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicated more subjective wealth.

Procedure and Analysis

All procedures were conducted online. Participants agreed to participate in this study and answered each item mentioned above. R (ver. 4.1.0) statistical software was used for the analysis. Multiple regression analysis was conducted to test the hypotheses with attitudes toward young people and life satisfaction as dependent variables. Perceived ageism, old age identity, depressive tendencies, subjective wealth, cohabitation, work status, age, and gender were independent variables. Scale items, the data, and R scripts used in this study are available on the Open Science Framework (OSF) repository (https://osf.io/27hsj/).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

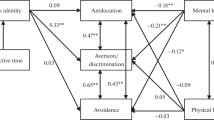

Means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients for each indicator are shown in Table 1. Participants with perceived greater ageism had more negative attitudes toward young people (r = 0.38, 95% CI = [0.33, 0.43], p < 0.001) and lower life satisfaction (r = –0.15, 95% CI = [‒0.21, –0.09], p < 0.001): hypotheses 1 and 2 were supported. Multiple regression analysis was also conducted using attitudes toward young people and life satisfaction as dependent variables. Perceived ageism, old age identity, depressive tendencies, subjective wealth, cohabitation, work status, age, and gender were independent variables (Table 2). The results showed that perceived ageism had a significant effect on negative attitudes toward young people (β = 0.36, 95% CI = [0.30, 0.42], p < 0.001) and life satisfaction (β = –0.09, 95% CI = [–0.14, –0.04], p < 0.001). Accordingly, participants perceiving more ageism directed toward them (1) had more negative attitudes toward young people and (2) had lower life satisfaction. These relationships were pronounced, even after considering the control variables, supporting hypotheses 1 and 2. Even when screening was conducted using the participants’ response time in this survey, hypotheses 1 and 2 were supported (see OSF repository).

In this study, we conducted an online survey of older Japanese participants to investigate the relationships between perceived ageism and (1) negative attitudes toward young people and (2) life satisfaction. The results showed that older adults with more perceived ageism had more negative attitudes toward young people and lower life satisfaction. Furthermore, these relationships were robust even after controlling for the participants’ difference variables, including old age identity and depressive tendency.

While empirical research is lacking on attitudes held by older adults toward young people [14, 21], we suggest that ageism directed by young people may strengthen older adults’ negative attitudes toward them. When people perceive negative attitudes directed toward them, they are more likely to view the other party unfavorably [16]. In addition, our findings suggest that young people’s ageism may reduce older adults’ life satisfaction. This result is consistent with numerous previous studies [5, 10, 13, 17, 18] reporting that ageism contributes to poor physical and mental health among older adults. Furthermore, a decline in older adults’ life satisfaction can reduce their social participation in many settings [22]. Thus, decreasing ageism toward older adults is essential to mitigate intergenerational conflicts and promote the mental health status of older adults.

Although the above findings were obtained in this study, there is a limitation in that we conducted only an online survey. In February 2022, when this study was conducted, the COVID-19 pandemic hindered face-to-face surveys with older adults. Therefore, participants in this study were limited to older adults who could participate in the online survey. They might have had better cognitive function and health status than the general population of older adults. Therefore, future surveys should be conducted with older participants selected by random sampling to examine the robustness of our findings.

CONCLUSIONS

This study found that older adults with more perceived ageism had more negative attitudes toward young people and lower life satisfaction. Ageism, which persists worldwide, might reinforce intergenerational conflicts between older adults and young people and worsen older adults’ mental health. Therefore, it is of primary importance to reduce intergenerational conflicts and encourage older adults to work, participate in society in a mentally healthy state [22], and play an active role as a valuable social resource. Although this study focused on older adults’ attitudes, the attitudes held by other generations should continue to be examined in detail. Studies aimed at reducing ageism should be actively conducted, in accordance with the research agenda of the Decade of Health Ageing 2020–2030 [26] and recommendations from existing literature [1, 13, 19].

REFERENCES

Burnes, D., Sheppard, C., Henderson, C.R., Jr., et al., Interventions to reduce ageism against older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Amer. J. Publ. Hlth, 2019, vol. 109, no. 8, pp. 1–9. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305123

Butler, R.N., Ageism: age discrimination, in The Encyclopedia of Aging: A Comprehensive Resource in Gerontology and Geriatrics, Schulz, R., Ed., Springer, 2006, рр. 41–42.

Chasteen, A.L., Pichora-Fuller, M.K., Dupuis, K., et al., Do negative views of aging influence memory and auditory performance through self-perceived abilities?, Psychol. Aging, 2015, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 881–893. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039723

Chen, L. and Zhang, Z., Community participation and subjective well-being of older adults: the roles of sense of community and neuroticism, Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Hlth, 2022, vol. 19, no. 6, 3261. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063261

Fragoso, A. and Fonseca, J., Combating ageism through adult education and learning, Soc. Sci., 2022, vol. 11, no. 3, 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11030110

Harada, K., Kobayashi, E., Fukaya, T., et al., Factors related to older adults’ negative attitudes toward young adults, Japanese J. Gerontol., 2019, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 28–37. https://doi.org/10.34393/rousha.41.1_28

Japan Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Population estimates, 2021. www.stat.go.jp/data/jinsui/.

Kessler, R.C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L.J., et al., Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress, Psychol. Med., 2002, vol. 32, no. 6, pp. 959–976. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291702006074

Kim, J. and Chung, S., Is an intergenerational program effective in increasing social capital among participants? A preliminary study in Korea, Sustainability, 2022, vol. 14, no. 3, р. 1796. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031796

Levy, B.R., Stereotype embodiment: a psychosocial approach to aging, Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci., 2009, vol. 18, no. 6, pp. 332–336. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01662.x

Marques, S., Mariano, J., Mendonca, J., et al., Determinants of ageism against older adults: a systematic review, Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Hlth, 2020, vol. 17, no. 7, 2560. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072560

McHugh, K.E., Three faces of ageism: society, image, and place, Ageing Soc., 2003, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 165–185. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X02001113

Molina-Luque, F., Stončikaitė, I., Torres-González, T., and Sanvicen-Torné, P., Profiguration, active ageing, and creativity: keys for quality of life and overcoming ageism, Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Hlth, 2022, vol. 19, no. 3, 1564. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031564

North, M.S. and Fiske, S.T., An inconvenienced youth? Ageism and its potential intergenerational roots, Psychol. Bull., 2012, vol. 138, no. 5, pp. 982–997. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027843

Onorato, R.S. and Turner, J.C., Fluidity in the self-concept: the shift from personal to social identity, Eur. J. Soc. Psychol., 2004, vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 257–278. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.195

Rosenberg, B.D. and Siegel, J.T., A 50-year review of psychological reactance theory: do not read this article, Motiv. Sci., 2018, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 281–300. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000091

Shimizu, Y., An overlooked perspective in psychological interventions to reduce anti-elderly discriminatory attitudes, Front. Psychol., 2021, vol. 12, 765394. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.765394

Shimizu, Y., Hashimoto, Y., and Karasawa, K., The complementation of the stereotype embodiment theory: focusing on the social identity theory, J. Hum. Environ. Stud., 2021, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 9–14. https://doi.org/10.4189/shes.19.9

Shimizu, Y., Hashimoto, Y., and Karasawa, K., Decreasing anti-elderly discriminatory attitudes: conducting a “Stereotype Embodiment Theory”-based intervention, Eur. J. Soc. Psychol., 2022, vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 174–190.https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2823

Skipper, A.D. and Rose, D.J., #BoomerRemover: COVID-19, ageism, and the intergenerational Twitter response, J. Aging Stud., 2021, vol. 57, р. 100929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2021.100929

Takeuchi, M. and Katagiri, K., A review of ageism research and its integration with aging research: from ageism to successful aging, Japanese Psychol. Rev., 2020, vol. 63, no. 4, pp. 355–374. https://doi.org/10.24602/sjpr.63.4_355

Turcotte, P.L., Carrier, A., Roy, V., and Levasseur, M., Occupational therapists’ contributions to fostering older adults’ social participation: a scoping review, Br. J. Occup. Ther., 2018, vol. 81, no. 8. pp. 427–449. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022617752067

Uemura, Z., Ambiguity tolerance, group identification, and attitudes toward newcomer acceptance, Japanese J. Pers., 2001, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 27–34. https://doi.org/10.2132/jjpjspp.10.1_27

United Nations, World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision, 2019. https://population.un.org/wpp/.

Urick, M.J., Hollensbe, E.C., Masterson, S.S., and Lyons, S.T., Understanding and managing intergenerational conflict: an examination of influences and strategies, Work Aging Retire., 2017, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 166–185. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waw009

World Health Organization, Decade of Healthy Ageing: Plan of Action, 2020. www.who.int/publications/m/item/decade-of-healthy-ageing-plan-of-action.

Yeung, D.Y., Isaacowitz, D.M., Lam, W.W., et al., Age differences in visual attention and responses to intergenerational and non-intergenerational workplace conflicts, Front. Psychol., 2090, vol. 12, р. 2090. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.604717

Funding

This work was supported by the Ph.D. program research grant from the University of Tokyo, and about “Research on Wellbeing in the 100-Year Life” from SAT laboratory LLC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval: This study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the University of Tokyo (UTSP-21 044).

Consent to participate: Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

Additional information

A part of this study was presented at the 2022 Annual Convention of the Japanese Group Dynamics Association.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shimizu, Y., Suzuki, M., Hata, Y. et al. Influence of Perceived Ageism on Older Adults: Focus on Attitudes toward Young People and Life Satisfaction. Adv Gerontol 12, 370–374 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1134/S2079057022040142

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1134/S2079057022040142