Abstract

This article uses Swedish register data to study the labour market experiences of radical right-wing candidates standing in local elections. We look at different measures of economic insecurity (labour market participation trajectories, experience of unemployment in social networks and relative growth in the number of jobs for foreign-born workers vis-a-vis natives) and examine whether they are predictors of candidates running for the Sweden Democrats, the main radical right-wing party in Sweden, as opposed to running for mainstream political parties. We find that the labour market trajectories of such candidates are markedly different from those of mainstream party candidates. Those with turbulent or out-of-labour market trajectories are much more likely to run for the Sweden Democrats, as opposed to other parties. The same is also true for candidates embedded in social networks with higher levels of unemployment, while working in a high-skilled industry markedly lowers the probability of running for the Sweden Democrats, especially for male candidates with low educational attainment. We find mixed results for the ethnic threat hypothesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The emergence and success of radical right parties in Western Europe is one of the most significant political developments in a generation. For a long time, Sweden was regarded as a country where radical right parties were excluded from mainstream politics. Historically, Swedish politics has been characterized by a high degree of class alignment, where low-skilled workers in manual occupations voted for left-wing parties that they trusted to represent their economic interests. Starting in the 2010s, the Sweden Democrats, a party which was initially limited to extremist circles in the 1980s and 1990s, surged in electoral support and in 2022 it emerged as the third-largest political party in the Swedish parliament. In contrast to established parties in Sweden, the Sweden Democrats have been increasing the number of their party members, reaching segments of the population which have not been active in politics before. This led some researchers to propose that Sweden Democrat politicians constitute a new class of citizens’ candidates, where candidates provide a credible representation to disgruntled segments of the electorate that were previously excluded from politics (Dal Bó et al. 2023).

The idea of political representation is at the heart of democratic political systems. In her book, "The Concept of Representation", Hanna Pitkin traces the history of the concept of descriptive representation. She focuses on the degree to which a person stands for others by being sufficiently like them and elaborates on the long historical tension between those who viewed descriptive representation as a necessary requirement for political representation and those who favoured alternative selection mechanisms. Pitkin argues that effective representation requires a degree of descriptive representation for representatives to understand the views and needs of their electorate (1967). Radical right-wing candidates provide an interesting exception to patterns of political entry where it is generally those with more education, affluence, and in white-collar jobs that are more likely to run for political offices (Carnes and Lupu 2015). Additionally, the labour market experiences of radical wing candidates also provide an insight into the descriptive representation of the electorate. Elsewhere, researchers have documented a trend of increased professionalization of politics and a disjoint in the life experiences of politicians from parties that historically sought to represent the working class and their target electorate, a trend that does not necessarily reflect the electorate’s preference (Cowley 2012; Norris and Lovenduski 1996; Carnes and Lupu 2016; Poertner 2022).

In this study of radical right candidates, we examine whether those who join the ranks of the Sweden Democrats are a different class of politicians than those running for established parties. Our data comes from longitudinal Swedish registers and allows us to look at the experiences of economic anxiety and status decline among the most dedicated supporters — political candidates. We adopt the economic insecurity framework and examine four different channels for economic marginalization: labour market participation trajectories, economic insecurity in social networks as well as the importance of the work milieu, and ethnic threat due to local differences in employment opportunities between native- and foreign-born workers. Since radical right-wing support and political entry are stratified by gender and education, our analysis is also stratified by these variables.

While numerous studies have looked at the influence of labour market experiences and economic insecurity on radical right voting, their role in political representation has only recently attracted researchers’ attention. We focus on unemployment, a marker of economic insecurity often used in research on the between economic insecurity and radical right-wing support (Jackman and Volpert 1996; Lubbers et al. 2002; Arzheimer and Carter 2006; Stubager and Ivarsflaten 2013; Sipma and Lubbers 2020). Additionally, we take a novel approach in that we look at employment trajectories over a longer period to study the impact of work life on the probability of standing as a candidate for the radical right. This approach, which rests on the use of sequence analysis, allows us to distinguish between different types of economically vulnerable trajectories. We find that turbulent and out-of- labour market employment trajectories are related to a higher probability of running for the radical right as opposed to mainstream parties. Overall, there is little evidence for ethnic threat competition, even when looking at trends in employment opportunities and wage patterns within local industries and local labour markets. Another finding relates to the impact of the work milieu where the same type of worker is predicted to have different probabilities of running depending on whether he or she works in a high- or low-skilled industry. Where we find significant effects, they tend to be for male candidates, which provides some support for the notion that other, non-economic factors could be important for women who decide to enter politics.

Literature review

Political entry

Radical right-wing support can manifest in various forms, and while the relationship between economic insecurity and this support is commonly discussed in terms of electoral backing, it is important to recognize the difference between voting and political candidacy. Unlike voting, political candidacy is a rare event, a public act, which in the case of radical right candidates can result in social ostracism. Political candidates are not representative of their electorate—they tend to be drawn from more affluent segments of the population, with fewer women and minorities. In their work on political entry, Norris and Lovenduski (1995) present a supply and demand framework for political recruitment which distinguishes factors influencing the supply of candidates from factors influencing the demand of party gatekeepers in making their selections. The first focuses on how social biases can arise in the supply of aspiring politicians. Even though the majority of eligible voters can also run as candidates, few make this decision. Constraints on resources (time, money, experience) and motivational factors (interest in politics, aspiration, drive) influence who passes the first stage of selection, from those eligible to run to those who aspire to become politicians. The biases at this stage emerge mostly because of differences in resources and motivation. The next stage is when candidates are nominated by party gatekeepers. Here, social biases in candidate selection reflect demand-size factors, that is the electorate’s direct and indirect discrimination where they are guided by whether candidates from, for instance, a manual working-class background, are evaluated as qualified or electable by their electorate. These biases represent a challenge to political representation and descriptive representation, i.e., the degree to which politicians’ characteristics and life experiences correspond to those of the electorate (Pitkin 1967).

Importantly, Norris and Lovenduski also observe that supply-size and demand-size factors interact, even at the first stage of candidate selection. An eligible candidate may become discouraged from pursuing a political career if she thinks that her background (sex, ethnicity, class) means that she would face discrimination. In the case of established parties, the experiences of economic insecurity and precariousness in working life have not been presented as an asset that could boost chances for successful selection. With the rise of radical right parties and their anti-elitist rhetoric, a new type of concern has taken centre stage: whether a political representative represents their electorate. The exclusion of certain segments of the population from the political process, combined with a shift in the politics of established left-wing parties, has been cited as a catalyst for political grievances exploited by political entrepreneurs from radical right-wing parties (Kriesi et al. 2008). It is no coincidence that a key theme in their rhetoric is the notion that mainstream parties are controlled by out-of-touch elites (Evans and Tilley 2017; Carnes and Lupu 2016). Meanwhile, radical right parties often position themselves as better representatives of those who feel left behind. In their recent study, Dal Bó and colleagues demonstrate that the pool of right-wing candidates in Sweden differs significantly from the pool of candidates of established parties, as individuals from economically marginalized groups are overrepresented in the former pool of politicians, including those with low labour market income and in occupations at risk of automation. The authors contextualize the trends among political candidates and voters by examining citizen-candidate models and the concept of descriptive representation (2023).

Individual economic insecurity

There are good reasons why candidates with experiences of economic insecurity could be seen as well-suited to represent the radical right electoral base. Unemployment and economic insecurity have been used as markers of economic insecurity in many seminal works on radical right support (Betz 1994; Jackman and Volpert 1996; Lubbers et al. 2002; Arzheimer and Carter 2006) although some discussion continues, for instance with regard to the size of the contextual effect or the ways in which economic insecurity variables are operationalized (Sipma and Lubbers 2020) Both factors are associated with an individual propensity to vote for the radical right (Lubbers et al. 2002, Abou-Chadi and Kurer 2021). Swedish studies report that unemployment is positively correlated with the share of the Sweden Democrats’ vote in electoral districts when controlling for immigration variables (which suggests some role of ethnic competition at a local level) and that economic uncertainty in the form of layoff notifications among low-skilled native workers is associated with a boost in the share of the electoral district vote going to the Sweden Democrats (Rydgren and Tyrberg 2020; Dehdari 2019). An issue that is often touched upon in the literature on the radical right next to unemployment or economic insecurity is the economic decline. Arguably, to study this concept we need a longitudinal approach. Being unemployed or at risk of unemployment is different from being of working age and out of the labour market for a long time. It is also possible that what matters for engagement with radical right-wing activism is not a trajectory of decline but instead a turbulent experience throughout working life.

H1

The probability of running as a candidate for the Sweden Democrats is higher for those affected by precarious employment histories, compared to the probability of running as a candidate for an established party.

Sociotropic effects of unemployment

Support for the radical right wing is geographically concentrated, especially in rural and post-industrial areas, which suggests that right-wing populism is rooted in regional differences in economic prosperity. Gidron and Hall (2017) note that regional decline seems closely coupled with cultural resentment; and the weakness of support for far-right populism in large metropolitan centres may reflect, not only relative prosperity but also the extent to which the experience of life within big cities promotes a distinctive cultural outlook. The consequences of unemployment can be far-reaching, not only at the individual level but also at the level of neighbourhoods, households, and larger social environments. Several studies suggest that people worry more about the impact of immigration and unemployment on society than on their own economic prospects (Hainmueller and Hopkins 2014; Berg 2015) or their household constellations (Abou-Chadi and Kurer 2021). The perception that unemployment is worsening as a collective, regional or national problem may have a greater impact on one's political behaviour than losing one’s job. While researchers often examine the impact of unemployment level in individuals’ residential areas (Sipma and Lubbers 2020) on support for the radical right, with register data it is possible to capture grievances over economic insecurity in social networks such as close and extended family members (Abou-Chadi and Kurer 2021) or middle-sized networks such as the workplace (Andersson and Dehdari 2021). The impact of sociotropic unemployment can also have an impact on supply-size explanations for candidacy, as these candidates feel most motivated to stand as candidates who represent the life experiences of those in their communities.

H2

The probability to run as a candidate for the Sweden Democrats is higher for those who have higher levels of unemployment in their social networks, compared to the probability of running as a candidate for an established party.

Work milieu

Another way in which social context can impact radical right-wing candidacy is the composition of one’s work milieu. Education level continues to be one of the most robust predictors of radical right support. According to Bornschier (2018), educational cleavages have been the single most important factor fostering the emergence of the radical right. This is because education affects a person’s position in the labour market and because it is related to characteristics such as openness to change and tolerance. These traits, in turn, make individuals more accepting of multiculturalism and the changes that come with it (Kriesi et al. 2008) Stubager also argues that higher education instils universalistic values (2008). His analysis of Danish survey data suggests that the association between education and differences in authoritarian-libertarian values is due to socialization and differences in the value sets transferred to individuals in different educational environments. Stubager concludes that the value difference between different educational attainment groups should be seen as arising because of a more fundamental value conflict and not as arising merely due to economic differences.

The educational setting is one domain, but if we develop Stubager’s idea further it is plausible that different work milieus can be associated with different propensities for endorsing radical right politics. Dividing labour market sectors into low-skilled and high-skilled, we expect that being part of a high-skilled sector would be associated with a lower individual propensity to support the radical right, on top of other characteristics. Workers with higher education have already been exposed to a more advanced educational milieu in the past, so we predict that the effect of being in a highly skilled work milieu would be highest for individuals whose skill level differs the most from their work environment—those with a basic level of education. An alternative mechanism giving rise to a similar pattern would be that of in-group conformity, where low-skilled workers adjust their political behaviour according to what is expected of them in a high-skilled work milieu.

H3

The probability of running for the Sweden Democrats would be lower for those working in high-skilled sectors, especially for workers with low educational attainment, compared to the probability of running as a candidate for an established party.

Ethnic threat

According to Sipma et al. (2022), the manual working class is more open to the radical right rhetoric because they see their labour market position as insecure due to threats from immigration and globalization. Responsiveness to demographic changes is the hallmark of a group threat response (Hopkins 2010) with the assumption that members of the majority group react with hostility when minority groups challenge their dominant status. Many studies (Rink et al. 2009; Savelkoul et al. 2017; Biggs and Knauss 2013; Valdez 2014) report that the radical right is more successful in areas with larger shares of immigrants; others report the opposite association or add additional conditions for when context becomes important. Contextual effects are one way to study ethnic competition, but occupation, firms or industries are other important contexts. Kunovich (2013) used US data to look at the numbers and shares of immigrants in different occupations, taking into account wage inequality, unemployment rate, employment growth and entry qualifications. A higher share of immigrant workers in an occupation was associated with a perceived group threat. Additionally, workers in growing occupations perceived immigrants as less of a threat. Kunovich argues that the association between attitudes and the share of immigrants in an occupation was largely spurious and arose because these occupations had a higher representation of low-educated workers. In another study on ethnic threat and the labour market, Pecoraro and Reudin (2020) report that Swiss workers who are more exposed to competition with foreigners in their occupations were more likely to express negative sentiments towards foreigners. Additionally, Pecoraro and Reudin looked at occupational unemployment and compared this with the share of foreign-born workers, finding that occupational unemployment rate was associated with more negative attitudes towards immigrants. Andersson and Dehdari (2021) looked at the presence of immigrants in Swedish workplaces and found that the increasing share of immigrant co-workers makes natives less inclined to support the radical right. The authors also found that this relation was driven by contacts between workers within firms. Anti-immigration rhetoric is central to the core message of radical right parties, and those who are at risk of unemployment or face high competition from immigrants are important target groups for these parties. Candidates coming from sectors with a higher exposure to immigrant competition may be more motivated to run for office, as their personal experiences can resonate with voters who link their job insecurity to immigration.

H4

The probability of running as a candidate for the Sweden Democrats is higher for persons working in an industry where there is more competition from foreign-born workers, compared to the probability of running as a candidate for an established party.

Data and methods

Data

Swedish full-population register data provide longitudinal individual-level information about the Swedish population. The registers contain socio-economic variables and information of whether individuals ever run in public elections. Our sample consists of the pool of candidates in the 2014 municipal elections, a total 53,594 individuals. Note that between 2010 and 2014 Sweden Democrats experienced rapid growth in the number of running candidates (and in fact struggled to fill their party lists) which suggests that at this time point internal party screening procedures were less stringent and those who wanted to run as candidates were welcomed to do so. Our independent variable is running as a candidate for the Sweden Democrats or not (i.e., running as a candidate for another party). It is worth noting that this likely affects the notion of demand-side factors affecting political candidacy in Norris and Lovenduski’s framework of political recruitment. Consequently, in case of the 2014 municipal election the supply of candidates likely had an even stronger influence for determining who became a candidate. We constructed variables for individual-level labor market participation trajectories, job insecurity in social networks, work milieu, and changes in local work opportunities. In addition, we controlled for individual demographic variables: age, sex, marital status, number of children in 2013.

Electoral context in Sweden

Sweden has a proportional representation electoral system with elections at three administrative levels (national, regional and municipal) held on the same day every four years. In this study, we focus on municipal elections. Municipal elections are characterized by low barriers of entry and are less competitive than parliamentary elections. In 2010 there were 52,000 people running for 13,000 seats in municipal elections. This translated to roughly 1:4 chance of success, compared to 1:17 for parliamentary elections. Municipal elections also have low formal minimum threshold required to have candidates elected (2% or 3% of votes depending on whether given municipality consists of a single constituency) that encourages small and new parties to run. Being a local politician is rarely a full-time job and usually there is no salary for one’s service. A vast majority of the elected local politicians are the so recreational politicians, apart from fees and renumeration for attended meetings they do not receive a regular salary for their service (SCB 2020).

Labor market participation trajectories

To examine if precarious employment labor market participation (LMP) trajectories are associated with higher likelihood to run for the Swedish Democrats, we created LMP statuses for each year from 2002 to 2012, i.e., ten years back from the time when the individuals registered as candidates for the 2014 election (November 2013). Due to our longitudinal approach, we limited our analysis to individuals who were approximately working-aged throughout the 10-year period, i.e., those who turned 19 or more in 2002 (normative age for leaving upper secondary education in Sweden) and at most 60 in 2012 (before the first chance to claim earnings-related pension). This left us with 33,176 candidates. We used the following categories:

-

1.

Employed (including parental leave and sick leave from work)

∙ Has income from work, disposable income higher than 60% of the median income in the municipality

- Ignoring short gaps due to parental leave from work, sick leave from work, or unemployment for less than 3 months in a given year

-

2.

Unemployed or underemployed

∙ Unemployed for 3 months or more in a given year or employed but disposable income less than 60% of the median income in the municipality

-

3.

Studies or education

∙ Gaining study benefit above the median level in a given year

-

4.

Living abroad

∙ Not employed, underemployed, or studying full-time (categories 1, 2, and 3) in a given year and registers showing living abroad for at least 6 months

-

5.

Inactive

∙ Retired or not in any other category

Underemployment and mainly unemployment states were combined due to the small number of candidates whose main activity was unemployment (more than 6 months in unemployment in a given year). To study patterns in LMP trajectories we used sequence analysis (SA), a method concerned with analyzing ordered social processes and a holistic analysis of life course (Ritschard and Studer 2018). Combined with cluster analysis, the approach is well suited for classification of complex life course trajectories such as LMP patterns as it allows for grouping trajectories based on different characteristics such as timing, duration, and order of labor market statuses or transitions. For example, we can differentiate between different types of precariousness including earlier and more recent career instability.

In short, using a suitable dissimilarity measure we calculated pairwise dissimilarities between individual LMP trajectories and then used cluster analysis for grouping similar sequences together. Finally, we formed a categorical variable based on cluster memberships. More precisely, we used optimal matching between sequences of spells with an expansion cost of 1 (OMspell; Studer & Ritschard et al. 2015) as the dissimilarity measure. We chose this measure as it is generally sensitive to sequencing (order) and timing of events and resulted in interpretable clusters.

The OMspell measure requires setting so-called substitution costs, which should reflect the (dis)similarity of the labor market statuses. These were chosen theoretically, based on being able to differentiate favorable and precarious LMP states (Table 1). First, employment and self-employment were regarded as similar to each other but also similar to studies, as studies typically lead to more stable employment careers (substitution costs were set to 1; note that only the relations matter and the specific numbers are not meaningful). Second, un(der)employment and other reasons for being outside the labor market were regarded similar as both are unfavorable states in terms of stable employment histories (costs set to 1). Costs for comparing most dissimilar states was set to 3. The cost for comparing any state for being abroad was set to 2, since we have no information on LMP from these years. For clustering we used partitioning around medoids (PAM). For choosing the optimal number of clusters we used various measures of the quality of a clustering solution including average silhouette width and pseudo-R squared (Studer 2013) as well as the interpretability of the clustering solution.

Job insecurity in different social contexts

To test the social network hypothesis, we measured experiences of unemployment in different social contexts of the candidates:

Partner. We measure days in unemployment in 2009–2013 for a marital spouse (if married) or a cohabiting partner (if parent to common children—the only case where we can match cohabiting partners using register data).

Relatives. We measure days in unemployment in 2009–2013 among parents, children, siblings, aunts, uncles, and cousins, and calculate the average.

Neighborhood. Similarly, to relatives, but among the individuals living in the 100 m by 100 m square around candidate’s residence in 2013.

Workplace. Similarly, to relatives, but among the employees in the candidate's workplace in 2013.

In analyses, we show the results using a month (30 days) as the unit for easier interpretation.

Industry skill level and change in local work opportunities

We tested the work milieu hypothesis by comparing the probabilities for candidacy for the Sweden Democrats by industry skill level, education, and gender. Industry skill level was defined as a binary variable that separated between low-skill industries, where less than 30% of employees had tertiary education, and high-skill industries, where more than 30% of employees had tertiary education.

To test the ethnic threat hypothesis, we measured change in local work opportunities by counting annual numbers of employees within 17 industries in each labor market area (LMA, as defined in 2012), separated by skill-level (low/high) and origin (Swedish-/foreign-born). We then calculated the change from 2002 to 2012 in the number of employees in each skill–origin category separately for each industry–LMA pair. Finally, we categorized industry–LMA pairs into four categories where the number of employees (as illustrated in Fig. 1):

-

grew for the Swedish-born and shrank or grew at a slower pace for the foreign-born

-

grew for both groups but faster for the foreign-born

-

shrank for both groups

-

shrank for the Swedish-born and grew for the foreign-born.

More precisely, we defined an industry “growing” in a specific LMA when the number of employees in that industry within the LMA increased by 5% or more between 2002 and 2012. Similarly, we defined “growing faster” as growth being 5 percentage points (ppts) higher or more.

We matched individuals to their industries in 2012, or if they were not employed in 2012 or the information was missing, to the industry where they had last worked since 2002. We added a separate category for individuals who had no job in 2002–2012 or for whom all industry information was missing. Finally, we coded a separate category for candidates that worked in an industry that had less than five employees in 2002 in their local LMA, because any changes in such low numbers would be related to huge percentual growth or decline. We studied the change in local work opportunities separately by industry skill level.

Method

Initial analyses showed that candidates for the Sweden Democrats were in many ways distinct from candidates for mainstream parties.Footnote 1 For this reason, we focused on a binary outcome of being a candidate for the Sweden Democrats or not (i.e., candidate for any other party). We estimated logistic regression models, presenting the results using average marginal effects (AMEs) that are easy to interpret and allow straightforward comparisons between estimates (Mood 2010). Because we assumed that the results would differ by gender and education, we estimated separate models by gender and education level (this is equivalent to introducing three-way interactions between gender, education, and all other variables, but computationally simpler). Due to the small number of foreign-born candidates in the Sweden Democrats, we limited our main analyses to Swedish-born candidates only. We explained the Sweden Democrats candidacy using individual LMP trajectories (more precisely, cluster memberships) and unemployment in different social contexts. We also used the interaction of change in local work opportunities and industry skill level. Finally, we controlled for demographic variables: age, sex, marital status, and number of children in 2013. All analyses were done with R (R Core Team 2019), and the SA part was done using the TraMineR package (Gabadinho et al. 2011) and the WeightedCluster package (Studer 2013) (Table 1).

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics on candidates running in the 2014 Swedish municipal elections. Among women, most of the candidates (57%) have tertiary education and only 5% have at most basic education. Among men, about equal numbers of candidates have gymnasium or tertiary education (45% each) while 9% have at most basic education. The median years of birth in each gender–education group range from 1959 (men with basic education) to 1967 (women with tertiary education). The proportion of the Sweden Democrats candidates is the highest within the least educated groups for both genders (19% among men, 12% among women) and less common within the highest educated group (4% among men, 1% among women).

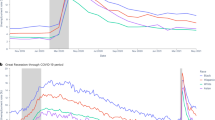

Labor market participation

We chose the eight-cluster solution as the most interpretable and suitable. It was successful in distinguishing stable (self-)employment as well as studies-to-work trajectories, long-term absence from the labour market, as well as earlier and later career breaks and “turbulent” employment histories (unemployed, underemployed, or moving between several LMP states). We further combined two clusters of studies followed by full-time employment since the main difference between the sequences in these clusters was the timing of the transition and this distinction was not regarded as important in the context of the study. Figure 2 presents the LMP trajectories in the seven clusters.

Seven clusters of candidates’ labor market participation trajectories. The horizontal axis shows years (2002–2012) and the vertical axis the candidates. One row represents the trajectory of one candidate. The rows are ordered according to the first dimension of multidimensional scaling so that similar sequences are shown close to each other

Table 3 shows descriptive information by LMP cluster. Continuous employment (disregarding breaks due to parental leave and sick leave from work) was the largest cluster with about half of the candidates and out of the LM was the smallest. The continuously employed group had the smallest average number of transitions between different states (on average 0.2 transitions per trajectory) while the turbulent cluster had the highest number of transitions (4.8 transitions).

Out of the LM cluster had the oldest candidates (median birth year 1958) and studies-to-work cluster the youngest (median birth year 1976). The share of women was lowest in the cluster of self-employed (24%) and highest in the studies-to-work cluster (56%). The share of foreign-born was the lowest in the continuously employed cluster (8%) and highest in the turbulent cluster (20%). The self-employed cluster had the lowest share of university-educated candidates (33%) while the studies-to-work cluster had the highest (83%). The number of the Swedish Democrats candidates was the smallest in the studies-to-work cluster (4%) and highest in the out of LM cluster (16%).

Unemployment in social environments

Table 4 shows percentiles for months in unemployment in different social contexts. The theoretical maximum number of months in unemployment is 60 during the five-year follow-up, but in practice the maxima were between approximately 40 months (3.3 years, among relatives) and 49 months (4.1 years, among co-workers).

Most candidates (87%) had no experience of spouse’s unemployment during the five-year follow-up. In other social contexts, the median was close to one month in all cases. The variation was the highest among relatives where the middle 50% of average unemployment is located between 3 days and approximately 2 months. Among co-workers the corresponding figures were between 18 days and 1.8 months and among neighbours, between 0.3 days and 2.2 months.

Change in local work opportunities

We also observed how the local labor market changed for candidates in different industries and skill levels. Figure 3 shows the distribution of the local work opportunities. Most candidates (52–67% depending on gender and education level) worked in industries that were growing overall but faster for the foreign-born (it is good to keep in mind that the number of foreign-born residents was growing in Sweden overall). The second largest but a much smaller category was working for an industry where the number of foreign-born employees was growing, and the number of Swedish-born employees was shrinking within their LMA.

Modelling candidacy for the Sweden Democrats

H1

Precarious employment.

Figure 4 shows the change in probability for candidacy for the Sweden Democrats by labor market participation cluster, origin, and education level when compared to continuous employment. The figures are based on the full model which accounts for covariates.

Average marginal effects and 95% confidence intervals for an increase in the probability of being a candidate for the Sweden Democrats (as opposed to other mainstream parties) by labor market participation trajectory, separated by gender and education level and accounting for covariates. Reference category: continuous employment

We observed little variation by labor market participation trajectory among male candidates with tertiary education and no differences among similar women. The highest probabilities for the tertiary-educated were found among male candidates with turbulent histories and long spells of being out of the labor market (4–5 ppts). In general, the differences were small and/or not statistically significant between candidates with continuous employment, continuous self-employment, and studies to work trajectories, irrespective of gender or education. Male candidates with less than tertiary education combined with an early career break had 6–8 ppts increase in the probability for candidacy for the Sweden Democrats. Regarding later career breaks, we observed a stronger educational gradient: male candidates with tertiary education had an increase of less than 3 ppts and with gymnasium-level education 6 ppts while for the least educated there was an increase of as much as 17 ppts. This suggests that for the least educated men, more recent experiences of unemployment mattered more than more distant ones. Among women with gymnasium education, we observed a small positive increase (about 3 ppts) in the probability for candidacy for the Sweden Democrats for both career break groups as well as the studies to work group. For the least educated, the effects were negative, but not statistically significant. The largest differences were found among the turbulent trajectories and candidates who have been mainly out of the labor market for other reasons than studies or parental leave. For those with turbulent trajectories, the increases in men’s probability for candidacy for the Sweden Democrats were 17 ppts for the least educated, 7 ppts for the gymnasium-educated, and 4 ppts for the tertiary-educated. Among women, the only statistically significant difference was observed among the gymnasium educated. For candidates outside of the labor market, the differences were 19 ppts for men with basic education, 17 ppts for men with gymnasium education, and 5 ppts for tertiary education. For women the respective figures were 15 for basic education and 7 for gymnasium education. Highly educated women had no differences in their probability for the Sweden Democrats by labor market participation history. As a conclusion, we found support for H1 in that the candidates with more precarious employment histories were more likely to run for the Sweden Democrats rather than other parties, and the probabilities changed according to gender and education level so that the low-educated male candidates had the highest probabilities.

H2

Social networks.

Figure 5 shows results for candidates’ experiences of unemployment in different social contexts: partner (immediate family), relatives (extended family), workplace, and immediate neighborhood.

Average marginal effects and 95% confidence intervals for the increase in probability of being a candidate for Sweden Democrats (as opposed to other parties) per one month’s increase in average unemployment in different social contexts by gender and education level. The results are from the full models that adjust for covariates

All in all, effect sizes were much smaller than for candidates’ own experiences of precarious employment. For basic-educated men, we observed statistically significant differences in the probability of candidacy for the Sweden Democrats for longer unemployment spells for partners and relatives (0.6 and 1.3 ppts increase per month, respectively), but not for co-workers or neighbors. For men with gymnasium education, we observed statistically significant differences for partners’, relatives’, and neighbors’ unemployment (0.4, 1.3, and 0.8 ppts per month, respectively). For men with tertiary education, we observed statistically significant but small differences for partners’, neighbors’, and co-workers’ unemployment (0.2, 0.2, and 0.3 ppts per month, respectively). For women, the only statistically significant differences were found for the gymnasium-educated, where we observed an increase of 0.6 ppts per month for relatives’ unemployment and 0.3 ppts for unemployment in the neighborhood. Effect sizes were larger for the least educated women regarding unemployment in the workplace and among relatives, but these were not statistically significant. In conclusion, we found limited support for H2: many of the estimates were statistically significant, but the effect sizes were modest and there was variation by gender and education level.

H3

Work milieu.

Figure 6 shows the differences between working in a high-skill industry as opposed to a low-skill industry by gender and education. There was a clear educational gradient for men: similarly educated candidates working in high-skill industries had lower probabilities for candidacy for the Sweden Democrats in comparison to candidates working in industries with mainly low-skilled employees. The difference by industry skill level was the largest among those with the lowest education level themselves: the probabilities of candidacy for the Sweden Democrats decreased by 9 ppts for the basic-educated, 6 ppts for the gymnasium-educated, and 3 ppts for the tertiary-educated in comparison to candidates working in low-skilled industries. For female candidates, the estimates were also negative but small, and the only statistically significant difference was found among the gymnasium-educated (about 2 ppts). In conclusion, we found clear support for H3 for men, but not for women.

Average marginal effects and 95% confidence intervals for the probability of being a candidate for Sweden Democrats (as opposed to other parties) by industry skill level, separated by gender and education. Reference category: Working in a low-skill industry (where less than 30% of employees had tertiary education)

H4

Ethnic competition.

Figure 7 presents results for changes in local work opportunities for Swedish- and foreign-born employees by origin and industry skill level for men. For women, the numbers of candidates for the Sweden Democrats in different education-industry combinations were so small in the 2014 election that unfortunately we were not able to perform reliable analysis.

Average marginal effects and 95% confidence intervals for the increase in probability of being a candidate for Sweden Democrats (as opposed to other parties) by change in local work opportunities in 2002–2012 for Swedish-born men, differentiated by candidates’ education (colors) and industry skill level (panels). Low-skill industry refers to working in an industry where less than 30% of the employees had tertiary education. Reference category: The number of Swedish employees grows, and it grows faster than the number of foreign-born employees (Swe = Swedish-born, fb = foreign-born)

Generally, the effect sizes were consistently positive in the low-skill industry group and negative or zero for industries with more high-skilled employees as compared to working in industries where the job opportunities were growing faster for the Swedish-born. However, only two of the differences were statistically significant: an increase of 4 ppts in the probability of candidacy for the Sweden Democrats for gymnasium-educated male candidates working in low-skill industries that were growing overall but faster for the foreign-born employees, and a decrease of 9 ppts for gymnasium-educated male candidates working in more high-skill industries where the Swedish-born were losing jobs but the foreign-born gaining. As a conclusion, we found no convincing support for H4: the only (barely) statistically significant difference was found among men in upper secondary education, and even there the effect size was relatively small.

Discussion and conclusion

It has been argued that an important aspect distinguishing the radical right from established parties is that their politicians can be described as citizens’ candidates, whose life experiences provide a closer match to their voters. A recent paper by Dal Bó and colleagues shows that the disgruntled sections of the population who experienced economic insecurity due to economic transformations not only vote for the party but also join the party and run as candidates. They discuss economic models of citizenship candidates and argue that radical right-wing candidates appear credible to their electorate precisely because of their shared socioeconomic traits and experiences (2023). Our study finds a broad confirmation of the argument that local radical right-wing candidates represent a new and markedly different profile of aspiring politicians. While our findings are in line with results reported by Dal Bó et al., our study offers more insight into longer-term work life trajectories as we apply a novel approach of looking at labour market trajectories of political candidates.

We find that candidates for the Sweden Democrats in local elections have different labour market participation trajectories than mainstream candidates; their employment histories are to a higher degree marked by experiences of unemployment and underemployment as well as being out of the labour market. These employment histories also show by far the largest effect sizes because for some configurations (men with basic education), precarious employment histories were associated with an increase of nearly 20 ppts in the probability of running for the Sweden Democrats as opposed to running for other mainstream parties. Additionally, candidates running for the Sweden Democrats are embedded in social networks that are more marked by experiences of unemployment. Here, the effect of unemployment is small and most visible for networks of the extended family and for lower educational levels. For women, the effect sizes were small and mainly statistically insignificant, although it should be noted that the number of female candidates running for the Sweden Democrats was relatively low in the 2014 elections. This finding stands in contrast to the notion that unemployment necessarily undermines political participation (Marx and Ngujen 2016). At the same time, it should be emphasized that we observed almost no long-term unemployment among the candidates. So even though the candidates were negatively selected within the full population of the candidates, they seemed to be positively selected among their peer group.

The second largest effect sizes were found for the work milieu hypothesis, where we found a sizeable decrease in the probability of a candidate running for the Sweden Democrats, especially for male candidates with low education levels who were working in high-skilled industries. What could be happening here is either due to selection or social influence. The social influence could be an extension of that described by Stubager (2008), where industries with different skill levels instil different values among workers. Alternatively, this effect could be observed because running for the radical right is a public act, which could be met with sanctions, especially in environments with more highly skilled co-workers. The social ostracism has been documented by Art (2011) in his interviews with members of the Sweden Democrats, who mention fears of losing jobs as one of the obstacles to becoming activists. Therefore, an alternative interpretation is in-group conformity that prevents low-skilled workers from openly supporting the radical right.

Lastly, applying the ethnic competition hypothesis to explain candidacy for the Sweden Democrats yielded mixed results. One explanation for this is provided by contact theory, which proposes that meaningful inter-group interaction leads to a reduction in prejudice (Allport 1954). It is also possible that what matters more than trends in employment and competition for foreign-born workers is the industrial skill level that candidates are employed to use. Indeed, we observe that there are diverging probabilities for radical right candidacy for those employed in low- and high-skilled industries, and these results resemble our findings on the work milieu hypothesis. Additionally, we see that working in a high-skilled industry is associated with twice as large a reduction in the probability of running for the Sweden Democrats when compared to working in a low-skilled industry. The finding that the right-wing candidates are those who worked for industries that were growing overall but faster for the foreign-born could be related to the view that it is not those at the bottom of the economic hierarchy who are more supportive of the far right. According to Gidron and Hall, support for radical right parties is more common among those who have some status to defend (2017).

Regarding the potential limitations of this study, it is important to stress that this paper is not aiming to present a causal view of candidates’ recruitment. It is, therefore, plausible that the Sweden Democrats’ leadership could select candidates that accept the radical right-wing rhetoric of economic grievances, even though the fact that the party experienced a shortage of candidates wanting to stand in the 2014 elections makes this assumption somehow less likely. Second, our results may not be generalizable outside the context of local elections and Sweden. The threshold to becoming a candidate and especially a candidate for the radical right was low in 2014 as the Sweden Democrats had difficulties attracting enough candidates to fill all the seats that they gained (Jungar 2016). The payoff from holding an office is lower than in higher-order elections such as parliamentary elections where successful candidates receive a salary. At the same time, there are certain issues that set the Swedish context apart. For instance, it is known that those who are economically vulnerable have a higher chance of engaging in politics, even at the local level, when they can rely on the welfare state safety network (Swank and Betz 2003). Sweden has relatively generous welfare provisions and even for those with precarious labour market histories, there is a higher level of economic security than for those in a similar labour market position in liberal welfare regimes. Secondly, the professionalization of politics, especially at a local level where elections are less competitive, may be less of an issue in Sweden than for instance in the UK or the US. Beckman in his analysis of Swedish cabinets between 1917 and 2004 concludes that even at the top level of politics “the evidence does not support the thesis of an ongoing process towards increasing professionalization of the cabinet” (2007). We believe that the issue of descriptive representation is more acute in countries like the US or the UK where researchers have documented how the working class had been gradually excluded from political representation (Cowley 2012; Norris and Lovenduski 1996; Carnes and Lupu 2016). At the same time, the limited welfare safety network or the higher threshold for political entry that exists in other contexts can limit opportunities for entering politics for those with limited economic resources.

Notes

Mainstream parties in the Swedish context include Social Democrats (S), Moderates (M), Center Party (C), Liberals (L), Green Party (G), Left Party (V) and Christian Democrats (KD).

References

Allport, G. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Cambridge: Addison-Wesley.

Andersson, H., and S.H. Dehdari. 2021. Workplace contact and support for anti-immigration parties. American Political Science Review 15 (4): 1159–1174.

Abou-Chadi, T., and T. Kurer. 2021. Economic risk within the household and voting for the radical right. World Politics 73 (3): 482–511.

Art, D. 2011. Inside the Radical Right: The Development of Anti-immigrant Parties in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Arzheimer, K., and E. Carter. 2006. Political opportunity structures and right-wing extremist party success. European Journal of Political Research 45 (3): 419–443.

Beckman, L. 2007. The professionalization of politics reconsidered. A study of the Swedish Cabinet 1917–2004. Parliamentary Affairs 60 (1): 66–83.

Berg, J.A. 2015. Explaining attitudes toward immigrants and immigration policy: A review of the theoretical literature. Sociology Compass 9 (1): 23–34.

Betz, H.G. 1994. Radical Right-Wing Populism in Western Europe. Springer.

Biggs, M., and S. Knauss. 2012. Explaining membership in the British National Party: A multilevel analysis of contact and threat. European Sociological Review 28 (5): 633–646.

Bornschier, S. 2018. Globalization, cleavages, and the radical right. The Oxford handbook of the radical right, 212–238.

Carnes, N., and N. Lupu. 2015. Rethinking the comparative perspective on class and representation: Evidence from Latin America. American Journal of Political Science 59 (1): 1–18.

Carnes, N., and N. Lupu. 2016. Do voters dislike working-class candidates? Voter biases and the descriptive underrepresentation of the working class. American Political Science Review 110 (4): 832–844.

Coffé, H. 2018. Gender and the radical right. In The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right, 200–211. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cowley, P. 2012. Arise, novice leader! The continuing rise of the career politician in Britain. Politics 32 (1): 31–38.

Dal Bó, E., F. Finan, O. Folke, T. Persson, and J. Rickne. 2023. Economic and social outsiders but political insiders: Sweden’s populist radical right. The Review of Economic Studies 90 (2): 675–706.

Dehdari, S.H. 2021. Economic distress and support for radical right parties—evidence from Sweden. Comparative Political Studies, 55(2), 191–221.

Evans, G., and J. Tilley. 2017. The New Politics of Class: The Political Exclusion of the British Working Class. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gabadinho, A., G. Ritschard, N.S. Mueller, and M. Studer. 2011. Analyzing and visualizing state sequences in R with TraMineR. Journal of Statistical Software 40 (4): 1–37.

Gidron, N., and P.A. Hall. 2017. The politics of social status: Economic and cultural roots of the populist right. The British Journal of Sociology 68: S57–S84.

Hainmueller, J., and D.J. Hopkins. 2014. Public attitudes toward immigration. Annual Review of Political Science 17: 225–249.

Hopkins, D.J. 2010. Politicized places: Explaining where and when immigrants provoke local opposition. American Political Science Review 104 (1): 40–60.

Jackman, R.W., and K. Volpert. 1996. Conditions favoring parties of the extreme right in Western Europe. British Journal of Political Science 26 (4): 501–521.

Jungar, A.C. 2016. 7 The Sweden democrats. In Understanding Populist Party Organisation. Palgrave Studies in European Political Sociology, ed. R. Heinisch and O. Mazzoleni. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kriesi, H., E. Grande, R. Lachat, M. Dolezal, S. Bornschier, and T. Frey. 2008. West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kunovich, R.M. 2013. Labor market competition and anti-immigrant sentiment: Occupations as contexts. International Migration Review 47 (3): 643–685.

Marx, P., and C. Nguyen. 2016. Are the unemployed less politically involved? A comparative study of internal political efficacy. European Sociological Review 32 (5): 634–648.

Mood, C. 2010. Logistic regression: Why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it. European Sociological Review 26 (1): 67–82.

Norris, P. 1997. Passages to Power: Legislative Recruitment in Advanced Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Norris, P., and J. Lovenduski. 1995. Political Recruitment: Gender, Race and Class in the British Parliament. Cambridge University Press.

Oesch, D., and L. Rennwald. 2018. Electoral competition in Europe’s new tripolar political space: Class voting for the left, centre-right and radical right. European Journal of Political Research 57 (4): 783–807.

Lubbers, M., M. Gijsberts, and P. Scheepers. 2002. Extreme right-wing voting in Western Europe. European Journal of Political Research 41 (3): 345–378.

Lucassen, G., and M. Lubbers. 2012. Who fears what? Explaining far-right-wing preference in Europe by distinguishing perceived cultural and economic ethnic threats. Comparative Political Studies 45 (5): 547–574.

Pecoraro, M., and D. Ruedin. 2020. Occupational exposure to foreigners and attitudes towards equal opportunities. Migration Studies 8 (3): 382–423.

Pitkin, H. F. (1967). The concept of representation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Poertner, M. 2022. Does political representation increase participation? Evidence from party candidate lotteries in Mexico. American Political Science Review 117 (2): 537–556.

R Core Team. 2019. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Ritschard, G., and M. Studer. 2018. Sequence analysis: Where are we, where are we going? In Sequence Analysis and Related Approaches. Life Course Research and Social Policies, vol. 10, ed. G. Ritschard and M. Studer. Cham: Springer.

Rydgren, J. 2007. The sociology of the radical right. Annual Review of Sociology 33: 241–262.

Rydgren, J., and M. Tyrberg. 2020. Contextual explanations of radical right-wing party support in Sweden: A multilevel analysis. European Societies 22 (5): 555–580.

Savelkoul, M., J. Laméris, and J. Tolsma. 2017. Neighbourhood ethnic composition and voting for the radical right in The Netherlands. The role of perceived neighbourhood threat and interethnic neighbourhood contact. European Sociological Review 33 (2): 209–224.

SCB. 2020. Förtroendevalda i kommuner och regioner 2019, available at https://www.scb.se/publikation/41398

Sipma, T., and M. Lubbers. 2020. Contextual-level unemployment and support for radical-right parties: A meta-analysis. Acta Politica 55 (3): 351–387.

Sipma, T., M. Lubbers, and N. Spierings. 2022. Working class economic insecurity and voting for radical right and radical left parties. Social Science Research 109: 102778.

Stubager, R. 2008. Education effects on authoritarian–libertarian values: A question of socialization. The British Journal of Sociology 59 (2): 327–350.

Ivarsflaten, E., and R. Stubager. 2013. Voting for the populist radical right in Western Europe: The role of education. In Class Politics and the Radical Right, ed. Jens Rydgren. New York: Routledge.

Studer, M. 2013. WeightedCluster library manual: A practical guide to creating typologies of trajectories in the social sciences with R.

Studer, M., and G. Ritschard. 2016. What matters in differences between life trajectories: A comparative review of sequence dissimilarity measures. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (statistics in Society) 179 (2): 481–511.

Swank, D., and H.G. Betz. 2003. Globalization, the welfare state and right-wing populism in Western Europe. Socio-Economic Review 1 (2): 215–245.

Valdez, S. 2014. Visibility and votes: A spatial analysis of anti-immigrant voting in Sweden. Migration Studies 2 (2): 162–188.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Stockholm University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Helske and Kawalerowicz are first equal contribution authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Helske, S., Kawalerowicz, J. Citizens’ candidates? Labour market experiences and radical right-wing candidates in the 2014 Swedish municipal elections. Acta Polit 59, 694–717 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-023-00304-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-023-00304-8