Abstract

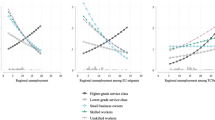

What is the impact of unemployment on far-right party support? This article develops a framework that links unemployment to far-right party support, while taking into account both the heterogeneity of the workforce and the role of labour market policies. More specifically, we focus on unemployment as a driver of economic insecurity and examine its effect on outsider and insider labour market groups. We identify the extent to which two labour market policies—unemployment benefits and Employment Protection Legislation (EPL)—mediate the effect of unemployment on economic insecurity, thus limiting the impact of unemployment on far-right party support. We carry out a large N analysis on a sample of 14 Western and 10 Eastern European countries between 1991 and 2013. We find that unemployment only leads to higher far-right support when unemployment benefits replacement rates are low. The results with regard to the mediating effect of EPL are more complex as EPL only mediates the impact of unemployment when we take into account the share of foreign-born population in the country.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We do not include Croatia due to the lack of data for EPL and countries that are not members of the European Union are not included in our analysis.

We follow the database classification except for the UK where we include UKIP as a far-right party in accordance with Immerzeel et al. 2015 and Halikiopoulou and Vlandas 2016 who include this borderline case in their respective classifications. For more details on how Armingeon et al. (2013) classify parties, see page 43 of their codebook.

We would like to thank Sabina Avdagic for sharing her data with us.

Including country fixed effects or country and time effects does not change the results for columns 1 and 2 in Table 1 (except for voter turnout which becomes insignificant with time effects). Note that whenever we include fixed effects Stata automatically drops our post-communist dummy variable as it becomes collinear (and similarly for time effects and our crisis dummy variable). For column 3 of Table 1, union density becomes significant when fixed effects are included (but loses significance again when time effects are added), while trade openness and voter turnout are robust to the inclusion of country effects but not of time effects. The unemployment benefit replacement rate retains significance throughout. Reproducing the results for Fig. 3 while including fixed effects results in non-significant results consistent with the notion that the effect we are picking up is cross-national, but running the regression with fixed effects in Fig. 4 does not change the results (we cannot re-estimate Fig. 4 with time effects as the latter are collinear with our crisis dummy variable). However, running the regression with fixed effects in Fig. 5 results in non-significant results again consistent with the notion that it is the cross-national variation in EPL, not the within country over time variation, that matters.

Excluding countries with very high (e.g. Sweden, Netherlands, France) or very low (e.g. UK, Greece, Poland) values of unemployment benefit does not change key result for unemployment benefit in column 1 of Table 1. Similarly, excluding countries with very high (e.g. Austria, Slovakia, Greece) or very low (e.g. Spain, Germany) votes for far right does not change key result for unemployment benefit in column 1 of Table 1.

The communist past is captured by dummy variable with value 1 for post-communist countries (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia).

The nonlinearity refers to EPL, i.e. in this case the interaction term takes the following form in Stata: c.EPL##c.EPL## c.Unemployment rate## c.Crisis dummy. (Thus, the nonlinearity is introduced only for EPL.)

References

Anderson, C., and J. Pontusson. 2007. Workers, worries and welfare states: Social protection and job insecurity in 15 OECD countries. European Journal of Political Research 46(2): 211–235.

Armingeon, K., V. Wenger, F. Wiedemeier, C. Isler, L. Knöpfel, D. Weisstanner, and S. Engler. 2013. Comparative political data set 1960-2013. Bern: Institute of Political Science, University of Berne.

Armingeon, K., Virginia F. Wenger, C. Wiedemeier, L. Knöpfel, D. Weisstanner, and S. Engler. 2017. Comparative political data set 1960–015. Bern: Institute of Political Science, University of Berne.

Arzheimer, K. 2009. ‘Contextual factors and the extreme right vote in Western Europe’, 1980–2002. American Journal of Political Science 53: 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00369.

Avdagic, Sabina. 2016. Causes and consequences of national variation in employment protection legislation in Central and Eastern Europe. [Data Collection]. Colchester, Essex: Economic and Social Research Council. https://doi.org/10.5255/ukda-sn-850598.

Bassanini, A., and R. Duval. 2006. ‘Employment patterns in OECD countries: Reassessing the role of policies and institutions’, in labour and social affairs Directorate for employment (ed.), Social, employment and migration working paper. Paris: OECD.

Bassanini, A., and R. Duval. 2009. Unemployment, institutions, and reform complementarities: Re-assessing the aggregate evidence for OECD countries. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 25(1): 40–59.

Betz, H.-G. 1994. Radical right-wing populism in Western Europe. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Carter, E. 2005. The extreme right in Western Europe. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Chung, H., and W. Van Oorschot. 2011. Institutions versus market forces: Explaining the employment insecurity of European individuals during (the beginning of) the financial crisis. Journal of European Social Policy 1(21): 287–301.

Clasen, Jochen, and Nico A. Siegel. 2007. Investigating welfare state change: The ‘dependent variable problem’. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

De Koster, W., P. Achterberg, and J. Van der Waal. 2012. The new right and the welfare state: The electoral relevance of welfare chauvinism and welfare populism in the Netherlands. International Political Science Review 34(1): 3–20.

Esping Andersen, G. 1990. Three world of welfare Capitalism. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Gallagher, M. 1991. Proportionality, disproportionality and electoral systems. Electoral Studies 10: 33–51.

Hainsworth, P. 2008. The extreme right in Western Europe. Abingdon: Routledge.

Halikiopoulou, D., and S. Vasilopoulou. 2016. Breaching the social contract: Crises of democratic representation and patterns of extreme right party support. Government and Opposition. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2015.43.

Halikiopoulou, D., and T. Vlandas. 2015. The rise of the far right in debtor and creditor European countries: The case of European Parliament elections. The Political Quarterly 86(2): 279–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12168.

Halikiopoulou, D., and T. Vlandas. 2016. Risks, costs and labour markets: Explaining cross-national patterns of far right party success in European Parliament elections. Journal of Common Market Studies. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12310.

Halikiopoulou, D., S. Mock, and S. Vasilopoulou. 2013. The civic zeitgeist: Nationalism and liberal values in the European radical right. Nations and Nationalism 19(1): 107–127.

Hernández, E., and H. Kriesi. 2016. The electoral consequences of the financial and economic crisis in Europe. European Journal of Political Research 55(2): 203–224.

Ignazi, P. 2003. Extreme right parties in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Immerzeel, T., et al. 2015. Competing with the radical right: Distances between the European radical right and other parties on typical radical right issue’s. Party Politics. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068814567975.

Inglehart, R., and P. Norris. 2016. Trump, Brexit, and the rise of populism: Economic have-nots and cultural backlash. Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Research Working Paper Series.

Ivarsflaten, E. 2008. What unites right-wing populists in Western Europe? Re-examining grievance mobilization models in seven successful cases. Comparative Political Studies 41: 3–23.

Kitschelt, H., and A. McGann. 1995. The radical right in Western Europe: A comparative analysis. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Koopmans, R., and P. Statham. 1999. Ethnic and civic conceptions of nationhood and the differential success of the extreme right in Germany and Italy. In How social movements matter, ed. M. Giugni, et al., 225–251. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Kriesi, H. 1999. Movements of the left, movements of the right: Putting the mobilization of two new types of social movement into political context. In Continuity and change in contemporary capitalism, ed. H. Kitschelt, et al. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kriesi, H., E. Grande, R. Lachat, M. Dolezal, S. Bornschier, and T. Frey. 2006. Globalisation and transformation of the national political space: Six European countries compared. European Journal of Political Research 45(6): 921–956.

Lipset, S.M. 1960. Political man: The social bases of politics. New York: Doubleday.

Lubbers, M., and P. Scheepers. 2002. French Front National Voting: A micro and macro perspective. Ethnic and Racial Studies 25(1): 120–149.

Lucassen, G., and M. Lubbers. 2012. Who fears what? Explaining far-right-wing preference in Europe by distinguishing perceived cultural and economic ethnic threats. Comparative Political Studies 45(5): 547–574.

Marx, P. 2014. Labour market risks and political preferences: The case of temporary employment. European Journal of Political Research 53(1): 136–159.

Mau, Steffen, Jan Mewes, and Nadine Schöneck. 2012. What determines subjective socio-economic insecurity? Context and class in comparative perspective. Socio-Economic Review 10: 655–682.

Mudde, C. 2007. Populist radical right parties in Europe. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Mudde, C. 2010. The populist radical right: A pathological normalcy. West European Politics 33(6): 1167–1186.

Norris, P. 2005. Radical right: Voters and parties in the electoral market. New York: Cambridge University Press.

OECD. 1994. Jobs study. Paris: OECD.

Plümper, T., V. Troeger, and P. Manow. 2005. Panel data analysis in comparative politics: Linking method to theory. European Journal of Political Research 44: 327–354.

Rueda, D. 2005. Insider–outsider politics in industrialized democracies: The challenge to social democratic parties. American Political Science Review 99: 61–74.

Rueda, D. 2006. Social democracy and active labour market policies: Insiders, outsiders, and the politics of employment promotion. British Journal of Political Science 36: 385–406.

Rueda, D. 2007. Social democracy inside out. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rydgren, J. 2007. The sociology of the radical right. The Annual Review of Sociology 33: 241–262.

Rydgren, J. 2008. Immigration sceptics, xenophobes or racists? Radical right-wing voting in six West European countries. European Journal of Political Research 47: 737–765.

Swank, D., and H.G. Betz. 2003. Globalization, the welfare state and right-wing populism in Western Europe. Socio-Economic Review 1: 215–245.

Van Vliet, O., and K. Caminada. 2012. Unemployment replacement rates dataset among 34 welfare states 1971–2009: An update, extension and modification of Scruggs Welfare State Entitlements Data Set, NEUJOBS Special Report No. 2, Leiden University.

Vasilopoulou, S., and D. Halikiopoulou. 2015. The Golden dawn’s nationalist solution: Explaining the rise of the far right in Greece. New York: Palgrave. ISBN 9781137487124.

Vlandas, T. 2013. The politics of temporary work deregulation in Europe: Solving the French puzzle. Politics and Society 41(3): 425–460.

Wimmer, A. 1997. Explaining xenophobia and racism: A critical review of current research approaches. Ethnic and Racial Studies 20(1): 17–41.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Tim Vlandas and Daphne Halikiopoulou have contributed to this article equally. The order of names reflects the principle of rotation.

Appendix: List of far-right parties in 14 West European and 10 East European countries, per country

Appendix: List of far-right parties in 14 West European and 10 East European countries, per country

Country | Far-right party |

|---|---|

Austria | Freedom Party (FPÖ) |

Austria | Alliance for the Future of Austria (BZÖ) |

Belgium | Democratic Union for the Respect of Labour (UDRT/RAD) |

Belgium | National Front (FN-NF) |

Belgium | Flemish Block |

Bulgaria | George Day-International Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (VMRO- Gergiovden) |

Bulgaria | Party Ataka (Nacionalno Obedinenie Ataka) |

Bulgaria | National Front for the Salvation of Bulgaria (DSB) |

Czech Republic | Rally for the Republic—Republican Party of Czechoslovakia (Sdruzení Pro Re- publiku—Republikánská Strana Československa, SPR-RSC) |

Czech Republic | Sovereignty/Jana Bobošíková Bloc (Suverenita/blok Jany Bobošíková, SUV) |

Czech Republic | Dawn of Direct Democracy of Tomio Okamura (Úsvit Přímé Demokracie Tomia Okamury, Usvit) |

Czech Republic | Party of Free Citizens (Strana svobodných občanů, SSO) |

Denmark | Danish People’s Party (DF) |

Estonia | Estonian Citizens (Eesti Kodanik) |

Estonia | Estonian National Independence Party (Eesti Rahvusliku Sõltumatuse Partei, ERSP) |

Estonia | Estonian Future Party (Tulevikupartei, TP) |

Estonia | Better Estonia + Estonian Citizens (Parem Eesti ja Eesti Kodanik, PE and EK) |

Finland | True Finns (PS) |

France | Front National (FN) |

Germany | National Democratic Party (NDP) |

Germany | Republicans |

Germany | Alternative for Germany (AfD) |

Greece | National Alignment, National Front (EM) |

Greece | Popular Orthodox Rally (LAOS) |

Greece | Independent Greeks (ANEL) |

Greece | Golden Dawn (GD) |

Hungary | Hungarian Justice and Life Party (Magyar Igazsag es Élet Partya, MIÉP) |

Hungary | For the Right Hungary (Jobbik) |

Ireland | N/A |

Italy | National Alliance (AN) |

Italy | Northern League (Lega Nord) |

Latvia | For Homeland (Fatherland) and Freedom TB |

Latvia | Latvian National Independence Movement (Latvijas Nacionālas Neatkarības Kustība, LNNK) |

Latvia | People’s (National) Movement for Latvia—Siegerist Party (Tautas Kustība Latvijai—Zīgerista Partija, TKL-ZP) |

Latvia | Alliance for Homeland and Freedom/Latvian National Independence Movement (TB/LNNK) |

Latvia | Everything for Latvia/For Fatherland and Freedom/LNNK (Visu Latvijai/TB/LNNK) (competed in 2011 under the name National Union [Nacionālā apvienība „Visu Latvijai!”—„Tēvzemei un Brīvībai/LNNK], NA) |

Lithuania | Lithuanian National Party ‘Young Lithuania’ (Lietuviu Nacionaline Partija ‘JaunojiLietuva’, LNP-JL) |

Lithuania | Lithuanian National Union List [comprised of Lithuanian National Union and Independent Party] |

Lithuania | Lithuanian National Union and Lithuanian Democratic Party |

Netherlands | Centre Democrats (CD) |

Netherlands | List Pim Fortuyn (LPF) |

Netherlands | Freedom Party (PVV) |

Norway | Progress Party |

Poland | Confederation for Independent Poland (Konfederacja Polski Niepodległej, KPN) |

Poland | Party X (Partia X) |

Poland | Movement for Rebuilding Poland (Ruch Odbudowy Polski, ROP) |

Portugal | N/A |

Romania | Greater Romania Party (Partidul România Mare) |

Romania | Party of National Unity of Romanians (Partidul Unităţii Naţionale Române PUNR), |

Slovakia | Slovak National Party (Slovenská národná strana, SNS) |

Slovakia | Movement for a Democratic Slovakia (Hnutie za demokratické Slovensko, HZDS, since 2006: L’S-HZDS) |

Slovakia | The Real Slovak National Party (Pravá Slovenská národná strana, PSNS) |

Slovakia | Movement for Democracy (Hnutie za demokraciu, HZD) |

Slovenia | Slovenian National Party (Slovenska Nacionalna Stranka, SNS) |

Spain | National Union (also included Falange Espanola, the Alianza Nacional and other neo-fascist groups) |

Sweden | New Democracy (NYD) |

Sweden | Sweden Democrats (SD) |

UK | United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vlandas, T., Halikiopoulou, D. Does unemployment matter? Economic insecurity, labour market policies and the far-right vote in Europe. Eur Polit Sci 18, 421–438 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-018-0161-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-018-0161-z