Abstract

That governments may not always keep their election promises or that they change policy positions may be unsurprising. However, failed promises, backing down on threats or flip-flopping on policy positions may be associated with a loss in support. Bringing together literature on the politics of electoral promises, policy shifts and audience costs, we examine the conditions under which a political leader can back down on a promise, using the EU referendum in the UK as a case study. Based on a survey experiment conducted in the aftermath of the 2015 general election, we examine whether justifications grounded on electoral motives, internal and external opposition would have allowed then Prime Minister David Cameron to avoid paying audience costs for going back on his campaign promise. Our results indicate that domestic audience costs might have been manageable, with only slightly more than a quarter of the participants in our study punishing executive inconsistency regardless of the justification employed. Of particular interest for European Union scholars, justifying backing down due to opposition from other EU member states is particularly effective in mitigating domestic audience costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Referenda have become an increasingly popular feature of the political landscape of European integration, with the UK’s Brexit referendum as the latest example of how these instruments of direct democracy can shape the course of domestic and international policy (Hobolt 2009). Since 1972, there have been 48 referendum votes held about matters related to the European integration in member and candidate states. Generally, in all but a few notable cases (e.g. Norway twice rejecting membership, Danish and Swedish rejection of the euro and Irish rejection of the Nice and Lisbon treaties, later reversed), outcomes have been in favour of further integration. Governing parties tend to use referenda on EU matters strategically, when the expected payoffs from the treaty reform are low, when they are confronted by Eurosceptic parliaments (Finke and König 2009), or to overcome intraparty divide (Oppermann 2013). Many have argued that it was precisely for this latter reason that a referendum on EU membership became a core campaign pledge of the Conservative party in 2015.

Bringing together literature on the politics of electoral promises, policy shifts and audience costs, we examine the conditions under which a political leader can back down on a campaign promise using the EU referendum in the UK as a case study. That governments do not always keep their election promises may be unsurprising. Yet they keep, or try to keep, most of them. Research of US presidents from Woodrow Wilson to Ronald Reagan shows that 75% of presidential campaign promises were either kept or only failed because of an uncooperative Congress (Fishel 1985). In the parliamentary responsible party government system of the United Kingdom, 88% of manifesto promises were fulfilled by British governments between 1987 and 2005 (Bara 2005).

In both democracies, however, this leaves a sizable number of campaign pledges that are broken. Sometimes, leaders appear to pay hefty domestic political costs—in terms of lower approval—from broken promises (e.g. George H. Bush’s pledge on ‘no new taxes’), yet at other times there is no apparent damage (e.g. President Obama’s promise to close down Guantanamo Bay). In this paper, we ask how the strategic tailoring of justifications might minimise the price, if any, that leaders and governments pay for broken campaign promises. We focus on one such campaign pledge: David Cameron’s promise to hold a referendum on the UK’s membership of the European Union (EU).

The Brexit referendum held on 23 June 2016 was part of the Conservative Party Manifesto for the 2015 UK general election. The promise to give people an opportunity to have their say on Europe was characterised by journalists, pundits and Cameron himself (Cowley and Kavanagh 2016) as one of the Tories’ core campaign pledges. Because of the direct appeal to public support, the threat to hold a referendum unless international actors—in this case, the EU—respond to the demands of a country’s government may be the ultimate test of audience costs (Tomz 2007; Levendusky and Horowitz 2012; Kroll and Leuffen 2016). Kroll and Leuffen (2016) have argued that the UK did not articulate clear á la carte demands in the EU negotiation process in 2016, finding that more specific demands would have ‘augmented audience costs’ (p. 1315). However, from the perspective of the public, we do not know what the actual audience costs would have been and whether they could have been avoided.

In audience costs theory, the threat of losing public support underpins the credibility of a threat. Nonetheless, there were several reasons to question whether the pledge to hold a referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU was actually a sincere commitment from the Prime Minister. First, the referendum was not entirely consistent with Cameron’s stance on Europe. Cameron’s call to ‘stop banging on about Europe’ when he became the Conservative party leader reflected his unease about raising the salience of Europe on the party agenda (Matthijs 2013). Some commentators argued Cameron felt ‘boxed in’ by his pledge rather than excited by the prospect of a referendum (McTague et al. 2016), and prominent Tory politicians like David Davis even argued that the Premier, once viewed as Eurosceptic, had ‘fallen under the influence of pro-EU Whitehall officials’ (Heffer 2016). Second, as the date of the 2015 election approached and opinion polls indicated that the Conservatives would not achieve an outright victory, the possibility that the referendum would be subject to coalition bargaining and eventually dropped from the agenda appeared tangible (Mason 2016).Footnote 1 Third, the potential political costs to Cameron within the Conservative party also provided some rationale for backing down from this campaign pledge. Since there was no certainty he could negotiate a new relationship with the EU that would satisfy Eurosceptic Tories, the Premier could be challenged by this vocal minority in the referendum campaign (Copsey and Haughton 2014). This opposition and a possible Leave outcome posed a serious threat to Cameron’s leadership.

These arguments suggest that the Prime Minister may have had incentives to avoid honouring the EU referendum pledge. Although the potential repercussions from public opinion could limit this option in practice, Cameron had backed out of another promise on the EU in the past, seemingly with little political cost. In 2009, prior to his win in the 2010 general election, the Conservative leader went back on his previous ‘cast iron guarantee’ to hold a referendum on the Lisbon Treaty, arguing that the agreement—which had by then been ratified by all member states—could no longer be undone through a referendum (Summers 2009).

The fact that leaders may escape punishment for inconsistencies or broken pledges underscores the role of strategic explanations in reducing audience costs (Levendusky and Horowitz 2012). Building on the initial work of Levendusky and Horowitz (2012), we ask what types of explanations are more successful at reducing the costs of broken campaign promises. Could Cameron have justified backing down from implementing the 2016 EU referendum without sizable loss of domestic support? Would alternative explanations for such executive inconsistency appeal to different segments of the electorate? Which segments of the public would be more or less likely to condone this broken promise?

This paper addresses these questions in the context of a survey experiment conducted in the aftermath of the 2015 UK general election, almost 6 months before the EU Referendum Act was approved in the House of Lords. We examine how alternative explanatory strategies seeking to rationalise the decision not to hold the referendum would have affected public approval of Cameron’s actions and perceptions about his competence. In so doing, we employ an empirical strategy that goes beyond a simple comparison of experimental treatments by allowing the possibility of heterogeneous treatment effects—i.e. that different groups of individuals may respond differently to alternative treatments, and that the logic and magnitude of the effects associated with these treatments may vary across participants. This enables us to assess how relevant dispositional characteristics moderate the relationship between executive justifications and the costs incumbents pay for breaking campaign promises.

Our analysis identifies and characterises a key group of individuals who would have supported Cameron backing down from his campaign promise, albeit only if it had been justified as a consequence of specific political pressures. This group constitutes more than 30% of our sample on an issue that subsequently divided the nation in a 48–52% split. Substantively, these results suggest that ‘strategic tailoring’ of justifications for going back on campaign pledges may be able to mitigate the costs to government accountability. Although it is impossible to know what the actual downstream effects might have been, how Cameron’s Eurosceptic backbenchers would have reacted or whether the government could have successfully managed to control how backing down was framed, our point is that the immediate political costs might not have been necessarily substantial. Instructive from the perspective of European politics is that, in the case of the Brexit referendum, not holding the vote due to the opposition from EU members could have been as credible and effective as justifications based on domestic pressures.

Avoiding audience costs with a good explanation: prior research and expectations

Although audience costs theory has been primarily applied in the realm of coercive foreign policies (Tomz 2007; Levendusky and Horowitz 2012; Thomson 2016), its logic at the micro-level can be extrapolated to issues that straddle the domestic/international divide such as the EU referendum. Audience costs refer to the loss in support faced by political leaders who back down after having publicly committed to a specific course of action. Publicly committing to the implementation of a policy heightens its credibility vis-à-vis international leaders, as they know that democratic politicians who break public promises face potential backlashes at home (Levy 2012). At an international level, committing to carry out a referendum signalled to EU members that the UK was resolved to leave the union if its demands for a ‘new settlement’ for Britain in Europe were not taken seriously (Kroll and Leuffen 2016). At a domestic level, it signalled to voters that the UK Independence Party (UKIP) was not the only choice for those with anti-European—or anti-immigrant—sentiments. At a party level, it had the potential to appease Eurosceptic Tories (Matthijs 2013; Copsey and Haughton 2014).

The credibility of threats rests on the role of public opinion in democracies—that the public does indeed punish leaders for backing down from promised actions. Tomz (2007) was the first to explore audience costs using experimental methods, showing that incumbent approval declines when threats are not carried out. This result is consistent with the ‘negative disconfirmation’ paradigm (Oliver 1997) that underpins research on advertising and product failure. When applied to campaign pledges, disapproval and vote loss result when candidates or leaders are inconsistent or break their promises (Karande et al. 2008). Like consumers, voters choose a candidate based on expectations, attitudes and past performances. Campaign promises act as advertisements for candidates and thus, when promises are not delivered (negative disconfirmation), voters become dissatisfied.

Research on the implications of candidate and party repositioning suggests that the promise of holding an EU referendum is precisely the type of issue where there may be sizable costs associated with changing positions. As discussed by Tavits (2007), the political costs leaders and parties pay for modifying their policy stances are largely dependent on the policy domain. The author argues that policy shifts on ‘pragmatic’ (e.g. economic) issues may be perceived as an active response to changing environmental conditions and thus condoned—or even rewarded—by the electorate. By contrast, public opinion is much less forgiving of swings on ‘principled’ policy domains such as those related to social and cultural values. Following this line of reasoning, and to the extent that citizens’ response to the EU referendum was predominantly based on concerns about multiculturalism and immigration (Hobolt 2016), dissatisfaction with a broken promise may be particularly high.

However, dissatisfaction can be moderated. Prior research testing how audience costs are conditioned by domestic factors and applications of the ‘negative disconfirmation’ paradigm to the political realm suggest that explanations strategically tailored by political elites to justify broken promises matter to costs. Levendusky and Horowitz (2012) find that a good justification for executive inconsistency can reduce or even eliminate audience costs. Similarly, Karande et al. (2008) find that justifying broken promises in the name of the public good can reduce the negative impact on performance judgements, while Robinson (2017) shows that political elites can avoid the negative consequences of ‘flip-flopping’ on an issue by offering an explanation that persuades the public that the new position is the better one.

The content of the justification for the decision to back down can thus affect whether and to what extent the public will punish inconsistent leaders. While Levendusky and Horowitz (2012) examine the strategic tailoring of justifications in terms of the arrival of new information about the ‘quality’ of the decision, assessing the optimality of alternative courses of actions regarding the EU referendum is far from straightforward. Instead, based on attribution theory (Weiner 1986; McElroy 1991), we focus here on the role of external political actors and electoral circumstances as explanations for executive inconsistency. The particular justifications we consider reflect the strategic considerations the Conservative party was juggling around the time the pledge to hold the referendum was made, and which continued to be relevant in the days following the 2015 election: internal political opposition, external opposition from EU member states and domestic electoral concerns (Copsey and Haughton 2014; Kroll and Leuffen 2016).

Although the Tories achieved an—unexpected—outright win in the election, the size of the government majority was relatively slim, and some pundits warned about the risk of government defeat over unpopular or controversial pieces of legislation (Wright 2015)—the European Union Referendum Act 2015 among them. Labour and Liberal Democrats, which had a sizeable majority in the House of Lords, had already blocked the European Union Referendum Bill in 2014, and both parties—along with the Scottish National Party—hinted after the election that they would take advantage of the government’s relative weakness to contest some aspects of the new legislation (Oltermann 2015).

The reaction of other EU members to Britain’s withdrawal from the Union was another plausible reason to justify a decision to drop the referendum pledge. Several member states had expressed their willingness to inflict ‘punitive externalities’ (Rasmussen 2016) on the UK, and the potentially damaging economic consequences of a bitter divorce from the EU were often highlighted by those seeking to avoid a referendum (Preston 2016).

As for the third explanation, scholars have pointed out that the promise to hold a public vote on Britain’s membership of the EU had underlying electoral reasons, stemming from the desire to stop UKIP’s rise in the polls (Matthijs 2013; Hobolt 2016). UKIP’s leader Nigel Farage had repeatedly questioned the credibility of Cameron’s pledge, dismissing it as an electoral strategy and reminding his supporters of the Premier’s broken promise regarding the Lisbon Treaty (Mason 2014). Once the election results were known and the relatively poor performance of UKIP—which only obtained one MP—became apparent, the utility of the referendum as an electoral tool vanished.

Attribution theory suggests that justifications shifting blame away from incumbents who fail to deliver on their promises and focusing the responsibility on actors or circumstances over which the leader has little or no control might be particularly successful in minimising public opinion costs (McElroy 1991; Hobolt and Tilley 2014). This argument is also consistent with research on election campaigns demonstrating that candidate inconsistencies are less likely to be forgiven when the responsibility for such inconsistencies lies with the candidate, e.g. as a plan to obtain votes (Karande et al. 2008). Building from attribution theory, then, we expect that citizens will generally be more willing to forgive executive inconsistency when it is attributed to internal or external political pressures than when it is explained as the result of an electoral strategy. This is due to the fact that, while the final outcome—i.e. avoiding the Brexit referendum—may be the same in all three scenarios, only the last one places the blame for breaking the pledge entirely on the Prime Minister.Footnote 2 Moreover, and again in line with attribution theory, we expect citizens to be more likely to condone Cameron for reversing course due to external—rather than internal—political pressures, as the former are most distant from the Premier (see also Tavits 2007). These arguments are summarised in our first hypothesis (H.1): audience costs should be lowest when the decision not to hold the referendum is justified as a result of the opposition of other EU members, and highest when the pledge itself is portrayed only as an electoral strategy.

Generally, the microfoundations of audience costs that have been studied are national reputational costs following executive inconsistency, as well as damages to perceived executive competence (Levendusky and Horowitz 2012; Levy et al. 2015). Levendusky and Horowitz (2012) find perceptions of competence are important when deciding whether to punish a leader for backing down from a threat. However, Levy et al. (2015) show that perceptions of the competence of the leader are less affected by executive inconsistency. Royal Prerogative notwithstanding (Mills 2010), given that most tests of the microfoundations of audience costs have been conducted in the US, where the president is seen as directly responsible for foreign policy, the question remains whether leaders’ perceived competence in parliamentary systems also suffers for inconsistent behaviour. Our second hypothesis (H.2) is that given the more dispersed nature of foreign policy-making in parliamentary systems, leader competence ratings will be less negatively affected than government approval, regardless of the justification provided for executive inconsistency.

These first two hypotheses also speak to the literature on repositioning (e.g. Robinson 2017). Politicians may change policy positions over time in order to more closely align themselves with voters. However, these changes (seen as ‘flip-flops’) can put the politician in a negative light. The extant evidence shows that politicians who change positions can be viewed less favourably than those who may demonstrate a strong character by sticking to unfavourable positions (Kartik and McAffee 2007). This repositioning is found to influence perceptions of politicians’ character (e.g. trustworthiness) as well as overall evaluations (Doherty et al. 2016).

Our next set of hypotheses explores how the effectiveness of explanations for executive inconsistency varies across individuals. Although most research on audience costs has assumed largely homogeneous audiences that follow a unitary logic (Tomz 2007), the power of justifications in mitigating audience costs is likely to be contingent on political, socio-demographic and dispositional traits. As Kertzer and Brutger (2016) show, different types of people punish executive inconsistency for different reasons. By this logic, it is also reasonable to expect that different types of people may be more or less responsive to justifications and more or less willing to condone leaders whose actions do not match their words. Therefore, we draw from research on audience costs and attribution theory to derive expectations about the moderating impact that individuals’ characteristics have on their willingness to punish Cameron for backing down.

As demonstrated by Gomez and Wilson (2001), citizens’ level of political sophistication affects attributions of responsibility for political decisions and outcomes. The authors argue that ‘low sophisticates’—e.g. less-educated and politically knowledgeable individuals—tend to focus on single, obvious causes for such outcomes. ‘High sophisticates’, in contrast, are able to make complex attributions and to acknowledge that political processes may be influenced by multiple factors and circumstances. In the context of the EU referendum, we expect the latter group to be more open to understanding that political pressures might prevent the Premier from carrying out the referendum as promised. Thus, our third hypothesis (H.3) states that, all else equal, more politically sophisticated individuals should be more likely to forgive the broken pledge.

Additionally, recent work has shown that audience costs vary systematically with individuals’ substantive policy preferences (Chaudoin 2014; Kertzer and Brutger 2016). Consistent with this, and given the prominent place occupied by immigration in evaluations of the EU and debates around Brexit (Hobolt 2016), we expect citizens with anti-immigrant sentiments to be on average more supportive of the referendum, and thus less forgiving of any backsliding on holding the vote. This is our fourth hypothesis (H.4). Similarly, although party lines around Brexit were less marked than usual for political matters (Hobolt 2016), it is reasonable to expect that UKIP voters would be more likely to view the Prime Minister dimly as a result of any action that could prevent the referendum from taking place, given the centrality of this issue for their preferred party. Hence, audience costs should be higher among UKIP supporters than among other citizens (H.5).

Experimental design

To test these hypotheses, we conducted an experiment embedded in an online survey fielded by the market research firm Research Now 3 weeks after the 2015 general election (May 28–June 1). The pool of respondents consisted of 1,830 British citizens drawn from 571 constituencies distributed throughout England, Scotland and Wales. The sample was matched to the 2011 Census data on socio-demographic variables, and attitudinal/behavioural profiling was employed to further enhance its representativeness.Footnote 3

The first part of the survey gathered background information about participants’ socio-demographic characteristics, media consumption habits, political knowledge, attitudes towards immigration and party identification.Footnote 4 Individuals were then randomly assigned to one of the three treatments or to a control group.Footnote 5

All participants read the following introductory message: ‘During the election campaign, the Conservative party publicly pledged to hold an in–out referendum on the UK’s EU membership by 2017’. In the control group, respondents were told that the pledge would likely be honoured as promised. For individuals in the three treatment groups, however, the script went on to state that the new government was likely to renege on the party’s campaign promise. Following the arguments outlined in the previous section, the three treatments differed in terms of the justification for failing to deliver the Brexit referendum. The vignette seen by subjects in the first treatment condition blamed the internal political opposition faced by the Tories, stating that the government would probably not be able to pass the referendum bill due to its slim parliamentary majority. The text received by individuals allocated to the second treatment attributed responsibility to external opposition, asserting that the vote was unlikely to be held due to the strong objections of other EU members. The third manipulation placed the blame on the new government, explaining that it did not intend to hold the referendum and that the pledge was seen as an attempt to attract potential UKIP voters before the election. In this last treatment, we note that the source of the justification is not the government itself but rather ‘experts and pundits’.

In all cases, subjects learned about the government’s hypothetical course of action and the rationale behind it through ‘reliable press sources’. According to Copsey and Haughton (2014), the (print) media play a key role shaping British voters’ opinions on the EU. This allows us to avoid concerns about the treatment effects being driven by the credibility of the sources—e.g. Cameron, the European Council—rather than by the content of the justifications. The experimental scenarios are summarised in Table 1.

After receiving the treatments, participants were asked the following questions: ‘Do you approve/disapprove of the course of action that David Cameron is going to take regarding the referendum situation you just read about?’, and ‘What is your assessment of David Cameron’s competence regarding the referendum situation you just read about?’ Following Thomson (2016), responses to both items were coded on an ascending 11-point scale. However, since the approval and competence measures built from these responses exhibit significant skewness, we log-transformed them for the purpose of statistical analysis.Footnote 6 For robustness, we also replicated the analysis using the “raw” measures coded on their original scales. These results, presented in Section A.3 of the Online Appendix, are substantively identical to those reported below.

Empirical analysis

As an initial step in our analysis, Fig. 1 summarises the distribution of government approval (left panel) and perceived leader competence (right panel) in the treatment and control groups.

The figure reveals considerable differences in approval rates across experimental conditions: average approval is highest among individuals in the control (‘No action’) condition (7.0 on a scale from 0 to 10), and lowest (4.9) in the ‘Electoral Strategy’ scenario, with considerable variations between treatment groups. By contrast, Cameron’s perceived competence is much more stable across experimental conditions, ranging from 5.06 in the ‘Electoral Strategy’ scenario to 5.76 in the control group. The evidence in Fig. 1 thus provides preliminary support for the hypothesis that alternative justifications may be more or less effective in mitigating loss of support (H.1), and that executive approval is more strongly affected by backing down than leader competence (H.2).

To rigorously test these hypotheses, we estimate average treatment effects through weighted least squares given in Table 2.Footnote 7 Column (1) confirms that government approval is systematically lower among individuals in the treated groups (i.e. those who were told that the government would go back on its promise) than among subjects assigned to the control condition (who were told that the referendum would be held as promised). This supports the notion that domestic audience costs are paid following inconsistent behaviour across the board. However, as seen in the second column, the magnitude of these domestic audience costs depends on the specific explanation for backing down. In line with hypothesis H.1, government approval is significantly lower (i.e. audience costs are significantly higher) when the referendum is presented as a mere electoral strategy than when the decision not to hold it is justified as a result of domestic political or external opposition. The 95% confidence intervals for the treatment effects are: [− 3.15, − 1.87] for ‘Electoral Strategy’, [− 1.78, − 0.34] for ‘Internal Opposition’ and [− 1.63, − 0.03] for ‘EU Opposition’. The drop in approval is lowest on average when the decision not to hold the referendum is attributed to the opposition of other EU members, also in consonance with H.1, although differences between the ‘Internal’ and ‘EU Opposition’ justifications are not statistically significant.

The comparison between columns (1) and (3) of the table indicates that executive inconsistency affects approval ratings more so than perceived leader competence, in accordance with Hypothesis H.2. Furthermore, effects are lower on competence than on approval for each of the three explanations considered, as seen by contrasting columns (2) and (4). Acting inconsistently in the British parliamentary system translates into loss of approval, but does not undermine perceived leader competence as much.

In order to test hypotheses H.3–H.5, we incorporate participants’ education, partisanship and attitudes towards immigration among the regressors of the linear models, along with interactions between these predictors and the treatment indicators. Figure 2 reports the estimates for these interaction terms.

Moderating influence of education, anti-immigration attitudes and partisanship on the effect of justifications for backing down. The figure reports estimates of the interactions between alternative moderating variables (rows) and each treatment indicator (explanations for executive inconsistency), using government approval (left column) and perceived leader competence (right column) as outcomes. Circles give point estimates; vertical lines correspond to 95% confidence intervals

As seen in the upper-left panel, the interactions between the treatment variables and college education—taken as proxy for political sophistication—are all positive in the model for government approval, indicating that more educated respondents tend to be more likely to forgive the broken pledge than less sophisticated participants. This finding is in agreement with H.3, although only the interaction between ‘Electoral Strategy’ and college education is more than two standard deviations above zero.

By contrast, the interactions between anti-immigration attitudes and each of the treatment indicators are negative on average (middle-left panel). Hence, as stated in our fourth hypothesis (H.4), respondents holding less favourable views of immigration are less likely to approve of the government’s decision to go back on its promise. Once again, however, the moderating effect of anti-immigrant sentiments is only statistically significant among respondents who were presented with the ‘Electoral Strategy’ justification.

On the other hand, and contradicting hypothesis H.5, we do not find significant differences in audience costs between UKIP supporters and other respondents (lower-left panel of the figure). This finding lends some credence to the claim that individual positions in favour or against leaving the EU did not follow clear party lines (Hobolt 2016).

The right panel of Fig. 2, in turn, plots interaction terms for the model using leader competence as outcome. The signs of these estimates exhibit no clear patterns, and none of them is statistically distinguishable from zero.

Altogether, these results would suggest that the strategic tailoring of justifications is largely incapable of mitigating audience costs. The estimates in Table 2 show that executive inconsistency significantly reduces government approval and perceived leader competence, even if the magnitude of these declines varies across treatments. This table reports average effects, though, which might conceal disparities within the electorate: while some voters may strongly punish Cameron for failing to deliver on his campaign promise regardless of the reasons for such failure, others might be willing to condone him when presented with a convincing explanation. Figure 2, however, provides limited evidence of heterogeneous treatment effects: we only find significant differences among subjects exposed to the ‘Electoral Strategy’ condition, and even then, only for the approval measure.

Nonetheless, a thorough examination of treatment effect heterogeneity requires going beyond conventional regression analysis. While the linear regression models discussed above provide a first approximation to the analysis of differential effects, they exhibit two fundamental shortcomings. First, they treat the two outcomes—government approval and perceived leader competence—as independent. The arguments in Levendusky and Horowitz (2012), however, suggest that they may be closely intertwined. Failing to account for potential correlation between both outcomes would discard relevant statistical information regarding the joint impact of the moderating factors and might lead to spuriously (in)significant effects, as standard errors estimated from bivariate models may modify the findings from univariate analyses (Thum 1997).

More importantly, regression analysis assumes a deterministic relationship between moderators, treatments and outcomes. When assessing the interaction between any covariate—say, education—and a treatment indicator, this approach imposes the restrictive assumption that all other individual characteristics—partisanship, attitudes towards immigration, etc.—are held constant. In practice, however, education, attitudes towards immigration, partisanship and other socio-demographic characteristics are likely to vary simultaneously, all of them potentially intervening between treatments and outcomes. Including all these interactions into the specification would not only obscure the interpretation of the substantive results, but also lead to under-powered statistical tests and raise the probability of Type-I errors (Imai and Ratkovic 2013).

To overcome these limitations, we estimate a finite mixture model. This empirical approach identifies different sub-populations or ‘classes’ of voters that vary in terms of the conditioning influence that multiple individual characteristics simultaneously exert on the relationship between treatments and outcomes (Moffatt 2016). Classes reflect differences in subjects’ responsiveness to treatment, which are determined by the joint impact of—a potentially large number of—moderating factors; individuals assigned to a given experimental condition may belong to the same class or not, depending on how these moderating factors intervene between treatments and outcomes.Footnote 8 The effects of the experimental manipulations are estimated for each of the sub-populations identified in the data, and the estimates compared across them. Hence, besides being able to rigorously account for heterogeneous treatment effects, the mixture model also provides an easily interpretable way of representing differential effects by means of a few mutually exclusive classes of voters.

Three such classes are identified in our sampleFootnote 9:

- (1)

‘Strict punishers’, for whom all treatments lead to a reduction in both outcome variables. This group represents 27.8% of the participants in our study.

- (2)

‘Light punishers’, for whom executive inconsistency reduces government approval irrespective of the justification employed, but less so than among ‘Strict punishers’. Reneging on the promise to hold the EU referendum, however, does not significantly affect these subjects’ perceptions of Cameron’s competence. This is the largest class in our subject pool, comprising 41.1% of participants.

- (3)

‘Feeling cheated’, who object only to the explanation that the promise of a referendum was exclusively aimed at increasing the Conservative party’s support at the expense of UKIP. As for ‘Light punishers’, executive inconsistency only undermines government approval, but does not affect perceptions of Cameron’s competence. This category contains 31.1% of our subjects.

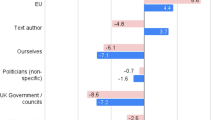

Figure 3 displays the effects of each treatment on government approval (left panel) and perceived leader competence (right panel) among members of the three classes.

Effect of justifications on government approval and perceived leader competence, by class. The figure plots treatment effects for each of the three classes of subjects identified by our finite mixture model. Dots represent point estimates (posterior means); whereas vertical lines give 95% highest posterior density (HPD) intervals. To facilitate the interpretation of the treatment effects, the estimates are transformed back to the original scale of the approval and competence measures

For ‘Strict punishers’ (Class 1), backing down from the EU referendum reduces approval of the decision and Cameron’s perceived competence by 1.53–2 points (14–18% on an 11-point scale). The magnitude of the effects is statistically indistinguishable across justifications, and is virtually identical for both outcomes. Government approval also decreases significantly under all treatment conditions among ‘Light punishers’ (Class 2), although the drop is considerably smaller—about 0.65 point, or 6%. But unlike for ‘Strict punishers’, reneging on his public commitment does not hurt Cameron’s perceived competence in this class.

The results are substantively different for the third class. For individuals who are ‘Feeling cheated’, government approval only diminishes significantly (by 1.69 points, or 15%) when they are told that the promise of a referendum was solely a strategy to win votes. Learning that Cameron reneged on his campaign promise due to internal opposition in parliament or to external pressures from other EU members has no effect on this group’s approval of the decision, and none of the treatments tarnishes the Prime Minister’s perceived competence.

Overall, the results emerging from Fig. 3 lead to more nuanced conclusions about the effectiveness of ‘strategic tailoring’ than those drawn from the simpler regression models. Once heterogeneous treatment effects are properly accounted for, we find that more than 30% of our subjects would have forgiven Cameron for failing to deliver on his promise to hold the EU referendum, provided such failure was attributed to internal political or external reasons. While ‘good’ explanations do not completely eliminate the political costs the incumbent would have paid for flip-flopping on this issue, they might have substantially reduced them.

Figure 4 sheds light on the composition of the three classes, displaying the impact of several individual characteristics on the probability of belonging to each class. The figure shows that the influence of these characteristics—intervening between treatments and outcomes—is not monolithic, and thus unlikely to be fully captured by standard interaction terms. The only exception is education, which has a straightforward effect on class assignment: having a university degree raises the probability of being a ‘Light’ rather than a ‘Strict punisher’ by 60%, and increases by 16% the likelihood of ‘Feeling cheated’.

Impact of respondents’ characteristics on the probability of class membership. The figure reports the impact of each covariate on the probability of belonging to Class 2 (‘lights punishers’) and Class 3 (‘feeling cheated’) relative to the baseline (Class 1—‘strict punishers’). Dots represent point estimates (posterior means), vertical lines give 95% HPD intervals

The effect of the other moderators is non-linear. Of particular interest is that Labour and UKIP supporters are evenly spread between the first and the third classes. The political implications of this result are important: they suggest that a non-trivial contingent of UKIP supporters would not have punished Cameron for going back on the promise to hold the referendum if this decision had been justified as a consequence of internal or EU political pressures. Conversely, many Labour supporters are in the ‘Strict punisher’ category, suggesting that although Labour had justified not committing to a referendum in its 2015 manifesto, there was some desire to see David Cameron fulfil the promise he had made. This is consistent with electoral returns indicating that many traditional Labour regions were supportive of Brexit.

Strikingly, the effect of attitudes towards immigration was not straightforward either. Although respondents ‘Feeling cheated’ are more likely to be pro-immigration than ‘Strict punishers’, there is no significant difference between ‘Strict’ and ‘Light’ punishers.

Finally, the results of our analysis partially contradict the claim that loss of executive approval is typically driven by whether citizens judge the actions of political leaders as competent or incompetent (Levendusky and Horowitz 2012). As reported in the Online Appendix (Sect. A.3), our estimates do show a strong positive association between approval of the government’s decision and perceived leader competence among ‘Strict punishers’: the posterior mean correlation between both outcomes for individuals in this class is 0.83, and the 95% highest posterior density interval (HPD) is [0.66, 0.98]. However, the correlation is much weaker for ‘Light punishers’ (0.01), with a credible interval overlapping zero. Among those ‘Feeling cheated’, the correlation between the two outcomes is actually negative (95% HPD interval: [− 0.38, − 0.20]).

Concluding remarks

Like many leaders before him, David Cameron had a choice after the 2015 election: Was he obligated to honour a risky election promise? What would be the costs of not doing so? Choosing to hold the referendum ultimately cost Cameron his job, but our main finding is simple: had Cameron backed down from his campaign pledge to carry out the EU referendum, domestic audience costs might have been manageable. Less than 28% of participants in our study were ‘Strict punishers’ for whom executive inconsistency would have translated into disapproval of the decision to the tune of 14–18% (relative to having carried out the referendum), and who would have viewed Cameron as significantly less competent for reneging on his promise. His perceived competence following inconsistent behaviour remained untarnished for more than 70% of respondents in the study. Furthermore, almost a third of our participants would not have punished Cameron if the failure to deliver on his promise had been justified on the grounds of internal or external political pressures.

Although our study focuses on the EU referendum in Britain, it contributes to the broader audience costs literature—and, specifically, to the growing body of empirical work examining the conditions under which audience costs apply. As argued by Levy (2012), ‘most likely case designs’ are particularly valuable as benchmarks to test the implications of audience costs theory: the higher the a priori probability that a case will satisfy the theory, the greater the inferential leverage of findings qualifying its propositions or providing additional insights into its analytical mechanisms. In this sense, the pledge to hold a referendum on the UK’s membership of the EU makes for an ideal case study, as reversing course on such a high-stakes commitment in a country where governments fulfil the vast majority of manifesto promises would reasonably be expected to carry considerable political costs. The fact that the strategic use of justifications may completely eliminate audience costs for a sizable segment of the electorate suggests that strategic tailoring can be even more effective in less salient policy domains and/or in polities where leaders are traditionally less accountable to their domestic publics (Levy 2012).

Our findings also have general implications for research on the politics of referenda on EU matters. Oppermann (2013) shows that governments frequently make a strategic use of EU referendum pledges for domestic political reasons—above all, as tools to paper over intraparty dissent on European integration and to reap potential electoral benefits when facing the challenge of Eurosceptic opposition parties. These are the most influential reasons explaining why European incumbents—Cameron among them—pledge referenda on the EU even when they are not obliged to do so (Oppermann 2013, pp. 692–693). As the author points out, though, such discretionary commitments entail considerable risk, since the odds of incumbent defeat in EU-related referenda tend to be increasingly high. Although generalising lessons from case-specific studies is always difficult, the results reported in this paper suggest that the strategic tailoring of justifications may help governments avoid this risk while attenuating domestic audience costs—especially when the blame for backing out of discretionary referendum pledges can be placed on factors outside incumbents’ control.

Finally, our work also adds to the literature on repositioning and elite framing of policy inconsistency. Research in this area suggests that elite accounts are most effective in alleviating the public opinion costs of flip-flopping when leaders explicitly accept responsibility for policy swings and are able to persuade the citizenry that their new stance is the better one (Robinson 2017). Our findings complement these results, showing that justifications can also be a powerful blame management tool, and that attributing responsibility for broken campaign promises to external actors or circumstances might substantially limit their negative consequences as well.

It is important to note, however, that incumbents may not always be able to control the way in which executive inconsistency is presented to the citizenry.Footnote 10 In some instances, governments may successfully impose their preferred narrative and attribute policy switches to causes outside their control—as with the justification underscoring pressures emerging from the EU. In other settings, though, governmental control over framing may be more limited. For instance, the most damaging justification considered in this study, namely that the promise of a referendum was an electoral ploy, would probably not be favoured by members of the incumbent party, but instead—as we noted above—highlighted by the opposition or the media. It is impossible to know what the actual audience costs of not implementing the EU referendum would had been, had the opposition managed to push this more costly ‘Electoral Strategy’ frame despite government efforts to the contrary. More generally, executive justifications may be countered by rival party elites or questioned by media commentators, who may offer alternative explanations for incumbents’ failure to deliver on their promises. The overall effects of such competitive framing on government evaluations may vary over time and across contexts, and which frame ultimately prevails will depend on the characteristics of the audience, the credibility of the sources, the dynamics of the political debate and the competitive environment (Robinson 2017). Therefore, we do not want to overstate our conclusion that Cameron would not have suffered by pulling back from the referendum promise over the long term. Nevertheless, our results do indicate that had the external pressure justification remained part of the discourse, the negative impacts might have been mitigated.

Notes

Even after election results were known, some doubts about the Tories’ capacity and willingness to call a referendum remained (e.g. Hitchens 2015).

This last explanation might not be used by the incumbent, but instead reflect a post-event framing or interpretation by the opposition and/or the media (e.g. labelling the referendum pledge as ‘insincere’ or ‘opportunistic’). In this sense, it may be considered an ‘accusation’, rather than a ‘justification’. Such ‘accusations’ or, more generally, the way in which the opposition, the media and other (non-incumbent) actors frame executive inconsistency—possibly conflicting with governments’ own accounts—can also shape domestic audience costs (Slantchev 2006; Robinson 2017).

Despite this, Table A.1 in the Online Appendix reveals some differences between the composition of the sample and of the population—especially regarding education levels. We account for these discrepancies by resorting to propensity-based adjustments (Lee 2006). See the Online Appendix (Sect. A.2) for details.

Definitions and coding for these variables are given in the Online Appendix (Sect. A.1).

We find no systematic imbalances between treatment and control groups (Online Appendix, Table A.2), indicating that randomisation was successful.

The mass of the distribution of responses is shifted towards the right for both questions, meaning that the majority of the participants express high levels of government approval and perceived leader competence. The distributions vary considerably across experimental conditions, though (see Table A.3 and Figures A.1 and A.2 in the Online Appendix).

These regression models incorporate propensity-based adjustment weights that render the composition of our sample statistically indistinguishable from that of the population (see Sect. A.2 in the Online Appendix). Ordinary least squares yield similar results (Online Appendix, Sect. A.3).

Classes may contain individuals with different levels of government approval or perceived leader competence, as long as their background characteristics affect their responsiveness to treatment in a similar fashion (Shahn and Madigan 2017).

We relied on the Deviance Information Criterion to choose the ‘optimal’ number of classes, comparing the fit of alternative specifications. As in the linear regression analysis, we used adjustment weights to enhance the representativeness of the sample. Sect. A.2 in the Online Appendix provides technical details about the finite mixture model and our estimation approach.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for raising this point.

References

Bara, J. 2005. A Question of Trust: Implementing Party Manifestos. Parliamentary Affairs 58 (5): 585–599.

Chaudoin, S. 2014. Promises or Policies? An Experimental Analysis of International Agreements and Audience Reaction. International Organization 68 (1): 235–256.

Copsey, N., and T. Haughton. 2014. Farewell Britannia? ‘Issue Capture’ and the Politics of David Cameron’s 2013 EU Referendum Pledge. Journal of Common Market Studies 52 (1): 74–89.

Cowley, P., and D. Kavanagh. 2016. The British General Election of 2015. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Doherty, D., C. Dowling, and M. Miller. 2016. When is Changing Policy Positions Costly for Politicians? Experimental Evidence. Political Behavior 38 (2): 455–484.

Finke, D., and T. König. 2009. Why Risk Popular Ratification Failure? A Comparative Analysis of the Choice of the Ratification Instrument in the 25 Member States of the EU. Constitutional Political Economy 20 (3–4): 341–365.

Fishel, J. 1985. Presidents and Promises: From Campaign Pledge to Presidential Performance. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press.

Gomez, B., and M. Wilson. 2001. Political Sophistication and Economic Voting in the American Electorate: A Theory of Heterogeneous Attribution. American Journal of Political Science 45 (4): 899–914.

Heffer, G. 2016. Cameron Abandoned Anti-EU Views After Becoming PM Due to Pro-Brussels Civil Service. Express, 26 May.

Hitchens, P. 2015. Why I Place No Hope in a Referendum on Britain’s EU Membership. Mail Online, 18 May.

Hobolt, S. 2009. Europe in Question: Referendums on European Integration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hobolt, S. 2016. The Brexit Vote: A Divided Nation, a Divided Continent. Journal of European Public Policy 23 (9): 1259–1277.

Hobolt, S., and J. Tilley. 2014. Blaming Europe?: Responsibility Without Accountability in the European Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Imai, K., and M. Ratkovic. 2013. Estimating Treatment Effect Heterogeneity in Randomized Program Evaluation. Annals of Applied Statistics 7 (1): 443–470.

Karande, K., M. Case, and T. Mady. 2008. When Does a Candidate’s Inconsistency Matter to the Voter? An Experimental Investigation. International Journal of Advertising 27 (1): 37–65.

Kartik, N., and P. McAffee. 2007. Signaling Character in Electoral Competition. American Economic Review 97 (3): 852–870.

Kertzer, J., and R. Brutger. 2016. Decomposing Audience Costs: Bringing the Audience Back into Audience Cost Theory. American Journal of Political Science 60 (1): 234–249.

Kroll, D., and D. Leuffen. 2016. Ties That Bind, Can Also Strangle: The Brexit Threat and the Hardships of Reforming the EU. Journal of European Public Policy 23 (9): 1311–1320.

Lee, S. 2006. Propensity Score Adjustment as a Weighting Scheme for Volunteer Panel Web Surveys. Journal of Official Statistics 22 (2): 329–343.

Levendusky, M., and M. Horowitz. 2012. When Backing Down Is the Right Decision: Partisanship, New Information, and Audience Costs. Journal of Politics 74 (2): 323–338.

Levy, J. 2012. Coercive Threats, Audience Costs, and Case Studies. Security Studies 21 (3): 383–390.

Levy, J., M. McKoy, P. Poast, and G. Wallace. 2015. Backing Out or Backing In? Commitment and Consistency in Audience Costs Theory. American Journal of Political Science 59 (4): 988–1001.

Mason, R. 2014. David Cameron: In-Out Referendum on EU by 2017 is Cast-Iron Pledge. The Guardian, May 11.

Mason, R. 2016. How Did UK End Up Voting to Leave the European Union? The Guardian, 24 June.

Matthijs, M. 2013. David Cameron’s Dangerous Game: The Folly of Flirting with an EU Exit. Foreign Affairs. 92 (5): 10–16.

McElroy, J. 1991. Attribution Theory Applied to Leadership: Lessons from Presidential Politics. Journal of Managerial Issues 3 (1): 90–106.

McTague, T., Spence, A., and Dovere. E. 2016. How David Cameron blew it. Politico, 25 June.

Mills, C. 2010. Parliamentary Approval for Military Action. London: House of Commons Library.

Moffatt, P. 2016. Experimetrics: Econometrics for Experimental Economics. London: Palgrave.

Oliver, R. 1997. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Oltermann, P. 2015. British EU Referendum: When, What and Who? Answers to the Key Questions. The Guardian, 26 May.

Oppermann, K. 2013. The Politics of Discretionary Government Commitments to European Integration Referendums. Journal of European Public Policy 20 (5): 684–701.

Preston, A. 2016. What Would Happen if Britain Left the EU? The Guardian, 19 April.

Rasmussen, M. 2016. ‘Heavy Fog in the Channel. Continent Cut Off?’ British Diplomatic Relations in Brussels after 2010. Journal of Common Market Studies 54 (3): 709–724.

Robinson, J. 2017. The Role of Elite Accounts in Mitigating the Negative Effects of Repositioning. Political Behavior 39 (3): 609–628.

Shahn, Z., and D. Madigan. 2017. Latent Class Mixture Models of Treatment Effect Heterogeneity. Bayesian Analysis 12 (3): 831–854.

Slantchev, B. 2006. Politicians, the Media, and Domestic Audience Costs. International Studies Quarterly 50 (2): 445–477.

Summers, D. 2009. David Cameron Admits Lisbon Treaty Referendum Campaign is Over. The Guardian, 4 November.

Tavits, M. 2007. Principle vs. Pragmatism: Policy Shifts and Political Competition. American Journal of Political Science 51 (1): 151–165.

Thomson, C. 2016. Public Support for Economic and Military Coercion and Audience Costs. British Journal of Politics and International Relations 18 (2): 407–421.

Thum, Y. 1997. Hierarchical Linear Models for Multivariate Outcomes. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics 22 (1): 77–108.

Tomz, M. 2007. Domestic Audience Costs in International Relations: An Experimental Approach. International Organizations 61 (4): 821–840.

Weiner, B. 1986. An Attributional Theory of Motivation and Emotion. New York: Springer.

Wright, O. 2015. Tories at Risk of Government Defeat as They Prepare to Protect Slim Majority. The Independent, May 26.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council ES/M010775/1 “Media in Context and the 2015 General Election: How Traditional and Social Media Shape Elections and Governing”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Banducci, S., Katz, G., Thomson, C. et al. A little justification goes a long way: audience costs and the EU referendum. Acta Polit 55, 305–326 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-018-0117-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-018-0117-x