Abstract

Patterns in candidate emergence affect who voters can choose from, and thus the quality of representative democracy. Despite extensive work considering factors that contribute to political ambition and factors that contribute to candidate emergence separately, we know less about the transition from the former to the latter. We investigate the role of motives using a novel dataset of over 10,000 open-ended statements of interest collected by Run for Something, a progressive non-profit that encourages political amateurs to run for state and local office. We find that politically ambitious future candidates talk about their interest in running differently than politically ambitious future non-candidates, suggesting that stated motives provide meaningful signals of likely candidate emergence. Respondents who articulated their motives in terms of general political interest, core values, and personal background were less likely to run than respondents who emphasized specific issues, political opportunity, or progressive populist sentiments, respectively. We further find that white and male respondents were likelier to articulate their interest in terms negatively associated with candidate emergence, consistent with prior work showing that members of underrepresented groups wait longer, until they are more qualified, before expressing their interest in running for office.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Representative democracy requires individual citizens to present themselves to their peers as candidate representatives. The correspondence between representatives and the represented will depend in large part on who is interested in seeking political office and who in fact becomes a political candidate – what previous scholarship has dubbed nascent and expressed political ambition (e.g., Fox and Lawless 2005; Lawless and Fox 2010). Representational inequalities are attributable not only to the choices voters make, but also to the choices voters are given. Inequalities at multiple points in the “pipeline to power” (Thomsen and King, 2020) can compound on themselves to frustrate descriptive representation, even when voters may prefer it (Schwartz and Coppock 2022).

Nascent and expressed political ambition occur at different stages of the candidate emergence pipeline (Maestas et al., 2006) and are therefore typically studied as distinct phenomena. Nascent political ambition is formed at Stage 1, when one first considers running for office, while emerging as a candidate occurs at Stage 2 once the decision to run is made. This distinction is important for theoretically separating factors that contribute to individuals’ personal interest in running for office from factors that could influence whether individuals act on that interest (Oliver and Conroy 2020).

However, as ambition and emergence tend to be studied independently, there is little empirical evidence regarding the factors that contribute to the transition from one to the next. That is, we know little about who among those with nascent political ambition are likeliest to become political candidates. Given that political candidacy is a rare event, much of the scholarship on this subject has studied political ambition and emergence separately, or restricted observation to high-status individuals who either already hold office or are in high-status occupations (see Gulzar 2020 for a review). Given limited access to data that observes candidate emergence among those identified as politically ambitious, it is difficult to gain empirical leverage on this transition. However, doing so is important for understanding, and potentially lowering, barriers for entry for desirable candidates, which affect representative democracy more broadly. This is especially important as scholarship identifies areas of incongruence between nascent and expressed ambition (e.g., Dynes et al., 2019).

We examine the transition from political ambition to candidate emergence using over 10,000 intake forms submitted to Run for Something, a left-leaning non-profit founded in 2017 with the goal of encouraging young, diverse political amateurs to run for state and local office. Run for Something recorded which of their respondents engaged in behaviors that indicate having emerged as a political candidate, such as filing to run for office or applying for the organization’s endorsement. Over 1,200 of these prospective candidates went on to run for office in either 2017 or 2018, providing a rare opportunity to observe patterns in candidate emergence conditional on a minimal demonstration of nascent political ambition in a context where running for office is not a prohibitively rare event.

We find that variation in prospective candidates’ stated motives for running for office is systematically associated with whether they actually run. That is, politically ambitious future candidates talk about their interest in running differently than politically ambitious future non-candidates. Prospective candidates who, when asked to write down why they were interested in running for office (their stated motive), emphasized specific policy issues or political opportunities were significantly more likely to actually run for office than prospective candidates who emphasized general political interest or national political dynamics (such as the election of Donald Trump).Footnote 1

Furthermore, we find that white and male prospective candidates were significantly more likely to articulate their interest using these less specific, more national themes. As such, white and male (and especially white male) prospective candidates ran for office at lower rates in these data than women and people of color (and especially women of color), despite accounting for a higher volume of both prospective and emerged candidates. Put simply, white men who submitted an intake form to Run for Something were likelier to engage in “cheap talk,” articulating their political ambition using themes negatively associated with candidate emergence. This suggests differences in the degree to which members of politically privileged versus marginalized groups used the intake form as an opportunity for general political expression, and that the bar for identifying as politically ambitious is higher for members of some groups than others. As such, in line with prior work (e.g., Carroll and Sanbonmatsu 2013; Shames et al., 2020; Dowe 2022), our findings support the contention that differences in nascent political ambition between privileged and marginalized groups should be interpreted with caution, as the weight of political ambition among the ambitious may exhibit different patterns.

Moreover, while highly general statements regarding one’s interest in running for office (e.g. “it’s something I’ve thought about for years;” or “I’ve always wanted to run”) correspond with typical markers of nascent political ambition – such as having previously thought about running for office in the abstract and the belief that one is qualified to do so – general interest alone at Stage 1 is less likely to translate into an emerged candidacy (Stage 2) than more specific motives. This distinction is important, as operationalizing nascent political ambition using measures such as how long someone has thought about running, or how many offices they’d consider running for, can obscure important variation in the depth and intensity of that ambition (Schneider and Sweet-Cushman 2020). Additionally, while surveys of ambition find perceptions of personal qualifications to be associated with nascent ambition (e.g., Fox and Lawless 2004; Oliver and Conroy 2020), references to one’s personal background did not emerge as an indicator of candidate emergence. Our analysis demonstrates the multifaceted nature of nascent political ambition by analyzing how it is articulated and demonstrates that stated motives are useful for understanding who among the ambitious is likely to run for office.

Background

There is a well-established empirical literature and rich theoretical tradition regarding patterns in nascent political ambition in the mass public (Fowler and McClure 1989; Crowder-Meyer 2020; Scott and Collins 2020); and there is a well-established empirical literature and rich theoretical tradition regarding patterns in political ambition among existing elected officials or those deemed “high-ability” (Schlesinger, 1966; Black, 1972; Rohde, 1979; Herrick and Thomas 2005; Lawless and Fox 2010; Preece and Stoddard 2015; Carroll and Sanbonmatsu 2013; Oliver and Conroy 2018, 2020; Clifford et al., 2019). However, scholars have not been able to learn nearly as much about the transition from being politically ambitious to emerging as a political candidate for the first time. We know less about patterns in running for office conditional on nascent political ambition, i.e., the transition from Stage 1 to Stage 2 of candidate emergence (Maestas et al., 2006).

One reason why we know less about this transition is limited access to relevant data. We can infer that a transition from being interested in running to actually running for office involves an interaction between intrinsic motivation, tangible resources, and opportunity (Lawless and Fox 2010; Thomsen, 2017a, b; Hall, 2019; Großer and Palfrey, 2019), but direct observation of any of these components is difficult to study prior to a transition from being interested in running for office to emerging as a candidate taking place. This leaves scholars with two primary approaches for making indirect inferences regarding this behavior (see Gulzar 2020 for a review). First, one can measure the latent proclivity of a person to run for office, often termed political ambition, without direct observation of candidate emergence. Second, one can measure candidate emergence within a selected population of individuals who are thought to be more likely to run to begin with, such as people in particular high-status professions or those who already hold lower-level offices.

These approaches are useful for understanding various obstacles to and advantages for candidacy, but are not ideal for understanding patterns in candidate emergence among those with nascent ambition more broadly. Interviews or other observational measures of already-emerged candidates typically cannot provide comparisons to similarly situated non-candidates (but see Bernhard, Shames, and Teele 2021, who interviewed individuals who intended to run for office but chose not to). Studies focused on specific professional fields cannot speak to how political emergence operates more widely, especially among non-elites for whom political ambition operates differently (Crowder-Meyer, 2020). However, in non-elite samples of the mass public, running for office is a prohibitively rare event to pair with political ambition on a survey.

Previous work relying on these approaches finds material resources and political opportunity to be crucial to launching a campaign (Stage 2). Launching and maintaining a campaign is one of the costliest forms of political participation, and these costs are often prohibitive for citizens who would otherwise be interested in public service or already possess nascent political ambition (Carnes, 2019). Beyond direct personal costs such as foregone wages from time taken off from work (Silberman, 2015), access to donor networks is typically critical for a successful campaign (Reckhow et al., 2017; Thomsen and Swers 2017b). Historically, higher earners, college graduates, and people born into wealthier families have been more likely to emerge as candidates for the U.S. House of Representatives than otherwise similar peers (Thompson et al., 2022). Similarly, changes in state legislature salaries affect the composition of their candidate pools (Hall, 2019), suggesting that low compensation discourages some would-be candidates from running. For this and other reasons, surveys of political ambition in the mass public, such as the Citizen Political Ambition Survey, often restrict their sample based on indicators such as education and employment status (Lawless and Fox 2010, 2017), or alumni of campaign training programs (e.g., Bernhard et al., 2021). The Candidate Emergence Study, another valuable set of survey-based evidence in this area, identifies a variety of means-based reasons why potential candidates wouldn’t be interested in running for office – such as fundraising or time constraints (Maestas et al., 2005, 2006).

Additionally, candidate emergence depends on the political opportunity structure, or availability of a viable path to office conditional on running (Schlesinger, 1966; Black, 1972; Rohde, 1979; Banks and Kiewet 1989; Herrick and Thomas 2005). The perception that winning is feasible – which can be understood as perceptions of political opportunity – undoubtedly affects patterns in candidate emergence (Maestas et al., 2006; Ondercin, 2020; Atsusaka, 2021). If the seat one is thinking of running for is currently occupied by an incumbent, or if one’s party organization prefers someone else for the nomination, then there is less of an opportunity to mount a successful campaign.

Party organizations can also influence opportunities to run for office through their recruitment and training efforts (Maestas et al., 2005; Sanbonmatsu, 2015; Oliver and Conroy 2018), as can the preferences of donor networks (Thomsen and Swers 2017b; Crowder-Meyer and Cooperman 2018; Ocampo, 2018). These organizations systematically prefer some potential candidates over others, with men typically reporting more recruitment contact than women (Moncrief et al., 2001; Windett, 2014) and local chairs of both major parties discounting the chances of non-white potential candidates’ electoral prospects in an experimental setting (Doherty and Dowling 2019). These preferences within party organizations can affect the political opportunity structure with clear implications for representational outcomes (Tolley, 2019). Importantly, the demographic makeup of jurisdictions influences the political opportunity for would-be candidates of color (Shah, 2014; Juenke and Shah, 2016). Last, in addition to material resources, political opportunity, and recruitment, Lawless and Fox (2010) find perceptions of qualification to influence candidate emergence (as well as nascent ambition). As such, subsequent scholarship has explored factors such as perceptions of political careers, personality traits, and socialization that contribute to the belief that one is qualified to run (e.g., Schneider et al., 2016; Oliver and Conroy 2020; Bauer, 2020).

We argue that stated motives among those who have expressed nascent ambition are useful for understanding variation in political ambition that is systematically associated with candidate emergence. Not only are the politically ambitious merely interested in running for office, but they can typically articulate specific reasons why. These reasons may be grounded in respondents’ personal identities, such as their race, gender, or sexual orientation (Bonneau and Kanthak 2020; Dowe 2020, 2022); personality traits (Blais et al., 2019; Dynes et al., 2021; Hart et al., 2022); ideology (Kirkland et al., 2022); or emotions such as empathy (Clifford et al., 2019) or anger (Scott and Collins 2020).

Separate strands of research identify personal or professional goals as motivations for running for office (Constantini, 1990; Herrick and Thomas 2005; Carroll and Sanbonmatsu 2013). Schneider et al. (2016) builds on this existing candidate emergence framework to argue that goal incongruity can partially explain gender disparities in political ambition, as political careers facilitate goals related to individual power, but women tend to seek out careers where they can serve others (see also Conroy and Green 2020). This would explain the smaller pool of women among the ambitious (Lawless and Fox 2010; Oliver and Conroy 2020). Finally, and relevant to our data and analyses, Hall (2019) argues that candidates are especially likely to be motivated by policy goals (to advance their policy agenda or block their opponents’ agendas) when the political offices in question are not well-compensated, as ideologically extreme prospective candidates will be more willing to bear the associated costs.

Data Collection

We examine the relationship between stated motives for nascent political ambition and candidate emergence using a unique dataset of intake forms collected by Run for Something, a non-profit founded in early 2017 by alumni of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign. The organization’s expressed goal is to encourage political amateurs to run for state and local office – especially those who are from traditionally underrepresented groups. While officially non-partisan, these characteristics mean that the organization attracts a predominantly liberal pool of prospective candidates. Although anyone interested in running for any office could fill out the organization’s intake form, which at the time of data collection was publicly available on its website, Run for Something focuses its efforts on local, down-ballot races such as school board, city council, and state legislature. The organization presents itself as a resource for citizens who are considering entering politics as a candidate for the first time.

Run for Something is one organization with a specific audience and goals, necessarily limiting the scope of our analyses. One important scope condition is the level at which Run for Something operates, with an explicit focus on down-ballot races. This may affect both the topics discussed in the statements of interest and their relationship with candidate emergence, relative to prospective candidates for federal office. In addition, given the political lean of the organization, the specific topics discussed in these statements of interest may not reflect the topics that would have been discussed in statements of interest for a similarly situated conservative organization.

Despite this, Run for Something’s size and goals make its pool of prospective candidates empirically interesting. Following its founding, Run for Something quickly became one of the more prominent organizations of its kind, emerging as a leading resource for those interested in entry-level political office. The organization’s significance is further evidenced by its sheer volume. Our data cover 1,211 candidates who ran for office in the 2017 and 2018 election cycles, emerging from 10,397 respondents who submitted a statement of interest.

Run for Something’s intake forms contain the following fields that we consider relevant for our analysis: ZIP code, race and gender, birth date, statement of interestFootnote 2 (an open-ended field in which respondents were invited to write in their own words why they were interested in running for office), and tags Run for Something added in association with various respondent-level characteristics relevant to the organization. Importantly, Run for Something did not use information from the intake forms to systematically encourage or discourage different types of respondents to run for office.Footnote 3 We fill in some missingness in reported race and gender, and append information regarding inferred education and household income levels, by matching respondents to a commercial voter file where possible.Footnote 4 Additional details regarding data collection and processing are included in the Appendix.

In addition to providing insights into how stated motives underlying nascent political ambition vary, the data provided by Run for Something are well-suited for addressing questions concerning the transition between nascent and expressed political ambition. By definition, every respondent has demonstrated at least some degree of nascent political ambition: they have given at least enough thought to running for office to take the tangible step of submitting a statement of interest to a candidate recruitment organization. If asked on a survey today whether they had ever previously thought about running for office, we would expect these respondents to say yes. While this distinguishes Run for Something respondents from citizens who lack any form of political ambition, this does not mean they have all demonstrated equal levels of nascent political ambition. It is possible that submitting a statement of interest means different things to different types of prospective candidate (Shames et al., 2020), and there may be systematic differences in the depth of interest signaled by filling out the organization’s intake form. If this is the case, then variation in the substantive content of statements of interest should be associated with candidate emergence.

Our primary analyses concern the statements of interest respondents submitted with their intake form on Run for Something’s website, which prompted respondents to articulate why they were interested in running for office. Most of these documents are relatively short, amounting to a few sentences (the interquartile region of word count in the statements of interest runs from 36 to 56 words), though some respondents wrote more (the longest document is 1,278 words).

After preprocessing the text for quantitative analysis (see Appendix for full preprocessing details), we implement pivoted text scaling (Hobbs 2019). Pivoted text scaling is a form of principal components analyses performed on a truncated word co-occurrence matrix, representing variation in word co-occurrence in low dimensional space. Its resulting dimensions are analogous to traditional principal components analysis in that they are orthogonal to one another and explain decreasing shares of variation in the word co-occurrence matrix. Words in the co-occurrence matrix are each assigned a score with respect to each dimension, and each document in the input data is assigned a score based on its average word score, in a manner analogous to word vectors.

The poles of each dimension identify “pivot” tokens that co-occur with relative frequency and tend not to co-occur with tokens on the opposite pole. This means that dimensions’ interpretations are relational. Using traditional topic modeling, we might interpret a given word or document as belonging to, or being “about,” a single topic. With pivot scaling, a document with an extreme score on a given dimension is interpreted as emphasizing one theme over another (and can have extreme values on more than one dimension). For example, Hobbs (2019) identified “patient protection” and “role of government” as poles of the first latent dimension in open-ended statements regarding the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Document scores on this dimension represented whether a respondent emphasized one of these themes over the other, and these scores were significantly associated with closed-ended stances regarding the policy.

Pivot scaling is well-suited for our data because it was developed specifically for short texts concerning similar topics, such as open-ended survey responses or social media posts (Hobbs 2019). The statements of interest we analyze are short documents responding to the same prompt: why the respondent is interested in running for office. We identify latent dimensions that explain the greatest amount of variation in what prospective candidates talked about when they expressed their interest in running for office, and quantitatively represent these dimensions at the word- and document-level. These quantitative representations of the text allow us to evaluate who expresses which types of motives, and whether these expressions of motives explain variation in who launched a campaign. Alternate analyses using structural topic modeling (STM) are shown in the Appendix and generate substantively similar results.

Results

Demographic Overview

Figure 1 shows the raw number of intake forms and emerged candidacies in the data at each combination of dichotomized race and gender. As the figure shows, pluralities of prospective and emerged candidates in our data are white men. However, white men also emerge as candidates at the lowest rate, with just 10% of intake forms being associated with a candidate for office. By contrast, 15% of women of color who submitted a statement of interest ran for office (additional descriptive comparisons can be found in the Appendix).

This descriptive result provides an initial indication that there may be systematic differences in how signaling political ambition implicates one’s likelihood of running for office, and that for members of some groups, an expression of nascent ambition is a higher bar. This aligns with previous research that shows women, compared to men, weigh the obligations associated with running for office differently (Carroll and Sanbonmatsu, 2013; Silberman, 2015; Bernhard et al., 2021), as well as research arguing that women who run are as electorally successful as men who run because they wait until they are more qualified to do so (Anzia and Berry, 2011; Fulton, 2012). Similarly, people of color, especially women of color, also face unique hurdles to political entry due to gender and racial bias, and thus likely navigate a more rigorous set of considerations before throwing their hat into the ring (Silva and Skulley 2019; Dowe 2022). These emergence differences at the intersection of race and gender shown in Fig. 1 demonstrate how the two-stage model of candidate emergence is useful for untangling how ambition operates. Here, it is possible that white women, and men and women of color grappling with more rigorous considerations may contribute to their higher rates of emergence shown in Fig. 1, which we explore in more depth, next.

Stated Motives and Candidate Emergence

Next, we present findings from the pivoted text scaling, which show systematic variation in how prospective candidates articulated their motives for running for office. Unlike topic modeling, where researchers typically identify a specific number of topics that best fits the data, pivot scaling does not offer an ideal number of dimensions to consider; they are simply returned in decreasing order of how much variation in the data they explain. We focus on the first three for two reasons: first, because the method is designed to represent the data in a low number of dimensions, and the first few dimensions typically provide the most explanatory power in the data (Hobbs 2019); second, because the poles of these dimensions are more interpretable than subsequent dimensions in our data. In an additional departure from topic modeling, as discussed above, the labels we provide for the poles of these dimensions are not “topics” in that they describe relative rather than absolute emphases.

Table 1 shows the top ten “pivot” tokens at the poles of each of these first three dimensions (tables for the first ten dimensions are shown in the Appendix). The associated tokens for the poles in the first dimension separate discussions of (a) general political interest and involvement (such as “getting off of the sidelines” or frustrations concerning Donald Trump), which we characterize as General Interest, on the negative pole from (b) discussion of specific policy issues (using terms such as invest, access, or affordable) on the positive pole, which we characterize as Specific Issues. The second dimension separates discussions of (a) respondents’ Core Values on the negative pole from (b) pragmatic discussions of local political dynamics, such as incumbents, legislative balances of power, and specific seats for which the respondent could run (Political Opportunities) on the positive pole. The third dimension separates (a) populist sentiments and criticism of Republicans (Progressive Populism) on the negative pole from (b) discussion of respondents’ backgrounds and personal characteristics, especially with respect to education, (Personal Background) on the positive pole.

Figure 2 plots the words that appear most frequently in the corpus overall with respect to the first two of these dimensions; Fig. 3 does the same with respect to dimensions one and three. These figures show how different word usage is associated with movement within the multidimensional space identified by the text scaling method. As shown in Fig. 2, words such as “Trump,” “enough,” and “possible” have negative scores on the first dimension (indicating that they are indicative of General Interest over Specific Issues), while words like “school,” “economy,” and “service” have positive scores on the first dimension (indicating an emphasis on Specific Issues over General Interest). Regardless of their location on the first dimension, scores near zero on the second dimension indicate that they have little bearing on whether the document in question is emphasizing Core Values over Political Opportunities or vice versa.

By contrast, words like “candidate,” “Democrat”, or “campaign” have high scores on the second dimension but are near zero on the first, indicating an emphasis on Political Opportunities over Core Values but not necessarily on General Interest or Specific Issues. Words like “society”, “together,” “democracy,” and “human” reflect an emphasis on Core Values over Political Opportunities with little bearing on the first dimension. However, some words have scores far from zero on both dimensions. A cluster of district-specific words like “board,” “county,” “council,” along with states and populous cities, are positive on both dimensions – indicating emphases on both Specific Issues and Political Opportunities.

Figure 3 includes the same frequently-occurring words and the same x-axis (Dimension 1 word scores), but plots them with respect to their Dimension 3 scores on the y-axis. This shows which commonly-used words denote emphases on Progressive Populism on the negative pole relative to Personal Backgrounds on the positive pole. For example, words like “corporate,” “money,” and “Republican” have distinctly negative scores on the third dimension, indicating emphases on Progressive Populism; while words like “career,” “graduate,” and “skill” have distinctly high scores on the third dimension, indicating a relative emphasis on Personal Background. We also note the small cluster of words in the top left of Fig. 3, such as “thought,” “think,” “always”, “involve,” and “consider,” that are often used in the context of the respondent indicating that they had previously thought about running for office or knew that they would want to run someday (this is discussed further in the Appendix). Taken together, the locations of these frequently-used words with respect to these first three dimensions helps contextualize the dominant forms of variation in how prospective candidates articulated their motives for running for office.

We further contextualize these themes by examining full statements of interest that fall on extreme ends of the first dimension (see Appendix for analogous consideration of the second and third dimension). For example, the following five documents are among the ten most extreme on the negative pole of the first dimension (“General Interest”). None of these respondents ran for office:

-

“Tired of sitting on the sidelines and complaining, and think it’s time to get started. Friends are always telling me that I should run for office.”

-

“I’m more energized than ever about politics since the election of Donald Trump. I feel as though I have something more to offer than just angry tweets (and my vote).”

-

“I’m sick of Donald Trump”.

-

“I’ve been involved in Twitter activism since Donald Trump was elected, to my complete and utter horror. But it’s now time for me to get off my couch and get civically involved. I’m ready to put myself out there for the good of the country. I’m ready to run for something.”

-

“I cannot sit back and watch the horrors of Trump Administration unfold and do nothing. Inspired by Bernie and seeing folks run who have never run before. Maybe I should too!”

These statements, which reference Twitter, Donald Trump, and general political interest, stand in stark contrast to the documents with the highest scores on the opposite end of that same dimension – the pole we refer to as Specific Issues. These documents are longer, so we limit presentation here to two, as well as edit them to remove locations and specific offices respondents referenced. Both of these respondents ran for office:

-

“I am a former [city name] public school teacher and have seen education from many angles, including working directly with underserved communities. We need culturally responsive education practices and policies focused on child wellness and equity embedded at every level of government. As [office], I will use my experience to support schools and empower the most important change-makers: educators, families, and students. The [city name] public education system needs to be a network of community-minded institutions and programs working together to support schools and empower communities. I have seen the power of afterschool programs in transforming students۪ lives by providing different outlets for learning and emotional support. I have seen the benefits both bilingual and monolingual students reap when they have access to dual language opportunities. Now more than ever, our kids cannot afford to grow up racially and culturally isolated when the society they will lead will be increasingly diverse. I have also seen how policies become more equitable and effective when educators and parents have an opportunity to weigh in and lead solutions. Each child deserves a great education. It is our responsibility, as a city, to be gatekeepers of opportunity and ensure ALL kids are set up for success. I am ready to work to ensure access to a high-quality education for every child in [city name].”

-

“I’m a community physician in [city name] hoping to expand the work I do everyday in my clinic out into the community to enact policy and legislation that will help people live healthier, more productive lives. I’m committed to: Health justice. Pass universal health care for all and take smart and compassionate action to tackle the opioid and obesity crises. Social justice. Fight for equality in public education, housing, and access to affordable and nutritious food. Economic justice. Support a living wage and paid family leave, and crack down on predatory lenders and job discrimination.”

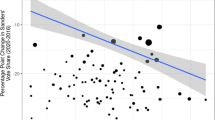

Descriptively, each of these first three dimensions are associated with candidate emergence. This is shown in Fig. 4, which plots the distributions of document scores by candidate status with respect to the first dimension on the x-axis and each of the next two dimensions on the y-axes, separated by facets. Candidates and non-candidates differ, on average, with respect to each of these three dimensions (each difference is statistically significant at p < .001). Specifically, candidates tend to have document scores that are higher on both the first and second dimensions, and lower on the third, than non-candidates. That is, respondents who emphasize Specific Issues over General Interest, respondents who emphasize Political Opportunities over Core Values, and respondents who emphasize Progressive Populism over their Personal Backgrounds are each more likely to have run for office.

We next assess how expressed motives varied between respondents with different demographic characteristics in Fig. 5. The figure plots coefficients from separate OLS regressions taking each of these three pivot scale dimensions as the outcome, respectively. Independent variables include all observed demographic indicators. As such, the results highlight not only the ways in which candidate emergence is associated with motives – in line with the above distributions – but also how motives varied between respondents with different demographic characteristics.

Coefficients in the figure represent movement along each pivot scale dimension associated with a unit change in the independent variable. For instance, the positive coefficient for Urban respondents (relative to Rural, the reference category) when the third dimension (Progressive Populism – Personal Background) is the outcome indicates that respondents from rural ZIP codes tended to emphasize Progressive Populism more, while their counterparts in urban (and suburban) ZIP codes placed relatively more emphasis on their Personal Backgrounds.

On the first dimension, we observe significant race and gender differences, with white and male respondents more likely to emphasize General Interest over Specific Issues compared to people of color and women, as well as suburban respondents compared to rural respondents, and younger respondents compared to older respondents. On the second dimension, we observe significant gender differences, with male respondents more likely to emphasize Political Opportunities over Core Values, than female respondents. Rural respondents were more likely to emphasize Political Opportunities over Core Values than suburban and urban respondents. On the third dimension, male and white respondents were more likely than female respondents and people of color, respectively, to emphasize Progressive Populism over Personal Background. We also note that older, lower-income, and non-college respondents also emphasized Progressive Populism over their Personal Background. In short, stated motives varied by respondents’ race, gender and geographic region, and to a lesser extent age and income.

Finally, we test the extent to which stated motives are informative of candidate emergence using a series of logistic regressions estimating the probability of running for office as a function of document scores with respect to the first three pivot scale dimensions. Document scores on each pivot scale dimension are normalized such that coefficients represent change in log-odds of running for office associated with a standard deviation increase. Reported results use all documents, with an additional indicator in the model for whether the document was cut off at 255 characters. All analyses are replicated in the Appendix with these observations excluded and show substantively similar results.

Coefficients from these regressions are plotted in Fig. 6 and show that each of the pivot scale dimensions are significantly associated with candidate emergence – with such associations robust to the inclusion of demographic covariates. Specifically, and in line with the distributions shown in Fig. 5, prospective candidates whose motives emphasized Specific Issues over General Interest, Political Opportunities over Core Values, or Progressive Populism over their Personal Background were significantly more likely to have run for office. We also find that older respondents, women, people of color, and people in rural areas were more likely to run for office even after accounting for what they wrote in their statement of interest.

Discussion

Political ambition is an important precursor to candidate emergence. However, as our analysis shows, not all ambition is created equal. People give different reasons when asked why they are interested in running for office, and our analysis identifies meaningful dimensions within these stated motives. Some citizens’ motives that underpin their interest in running for office are more congruent with the practical realities of actually doing so than others.’ As we show here, politically ambitious citizens who articulated their ambition in terms of general political interest, core values, and their personal backgrounds were less likely to actually run for office than those who emphasized specific policy issues, political opportunities, and progressive populism, respectively.

These findings are in some sense intuitive. While those who are broadly attentive to politics may be likely to have previously thought about running for office, and while left-leaning citizens frustrated with Donald Trump’s presidency may have been particularly motivated to seek information on how to become more politically active as well, these motives alone are not well-aligned with the practical realities of local politics. Citizens who filled out Run for Something’s intake form articulating a specific problem in their community they wanted to fix, or a specific office they felt they had a chance to win, were significantly more likely to make the transition from nascent to expressed political ambition. The former (a specific problem they want to fix), and the latter (a specific office they felt they could win), align with existing scholarship on ambition and candidate emergence that highlights the importance of seeing political candidacy as a feasible mechanism by which to achieve one’s policy goals to the transition from Stage 1 to Stage 2 of candidate emergence (Carroll and Sanbonmatsu, 2013; Schneider et al., 2016; Thomas and Wineinger 2020).

That respondents were sensitive to the political opportunity structure aligns with Schlesinger’s (1966) foundational argument that individuals will be likelier to run when the opportunity structure is more favorable. While that argument may be putting it too simply (Stone, 1980; Carroll and Sanbonmatsu, 2013), our findings show that prospective candidates who ran for office frequently expressed awareness of relevant district dynamics. This is in line with Blais and Pruysers’s (2017) conception of political ambition, which includes the desirability of a political career, one’s perception of whether they’re qualified for office, and expectations of electoral success alongside previous considerations of running for office.

Our findings do not rule out the possibility that citizens who articulated more specific motives were initially driven to become politically ambitious through more general or nationalized dynamics such as the election of Donald Trump. Indeed, many people become more politically aware and interested on account of nationalized politics and campaigns. However, our findings suggest that the transition from Stage 1 to Stage 2 of candidate emergence typically requires a more specific reason – regardless of whatever initially generated one’s interest. Those who used the space allocated to them in their statement of interest to talk about a general interest in running for office, or nationalized political dynamics, were less likely to make such a transition than those who articulated their interest in more specific terms.

Taken together, our findings suggest meaningful differences in how political ambition operates across individuals and groups. This is especially apparent in the demographic differences that emerge when we take the content of the statement of interest as our outcome variable: prospective candidates with more privileged identities (i.e., white men) were more likely to articulate their interest in running for office in more general terms, such as having previously considered running for office. This certainly counts as nascent political ambition, but it is qualitatively (and, as we show, quantitatively) distinct from articulating one’s ambition in terms of wanting to address specific policy issues in one’s community. Members of underrepresented groups face a different set of calculations when considering a candidacy and may be less likely to submit an intake form to a candidate recruitment organization in the first place without a more specific reason for doing so.

These findings contribute to our understanding of candidate emergence by providing a novel account of the transition between nascent and expressed political ambition and offer the potential for new avenues of related research. As discussed above, Run for Something encourages candidates largely to run for state and local offices, which rarely confront national issues, despite being a national organization. This limits the scope of the present work, though we see it as an empirically interesting tension amid the ongoing nationalization of local politics (e.g., Hopkins 2018). We are similarly limited in scope by the political lean of the organization we study. It may be the case that emphasizing specific policy issues over general political interest, or political opportunities over core values, is associated with candidate emergence among politically ambitious conservatives, but it is not obvious. While replicating this work with a conservative leaning organization would be important for further understanding these dynamics, we note that there are relatively few large-scale right-leaning organizations analogous to Run for Something (see Kreitzer and Osborng 2019, e.g., who document a large disparity in the number of Democratic- and Republican-aligned candidate training programs specifically oriented toward women), which could complicate such efforts.

Nevertheless, while our findings are specific to one organization with particular goals, they also represent a rare instance in which we can observe patterns in the transition from nascent to expressed ambition – and contextualize the nature of that ambition itself. This provides a useful complement to survey-based research, where the transition from nascent ambition to candidate emergence is typically too rare of an event to study systematically; as well as to interview-based or other observational research on emerged candidates, which are generally forced to select on the dependent variable. As such, we hope this work serves as a foundation for other scholars to further understand who among the politically ambitious is likely to run for office, and how inequalities in pipelines to power influence democratic representation.

Availability of data and materials

Replication materials for this manuscript can be found at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/SPOMK4.

Notes

This is not to say that the election of Donald Trump didn’t encourage political amateurs to run for office – there is evidence that it did (Riley and Smith 2018). Rather, this is to say that respondents who used the limited space allotted to them in their statement of interest to explicitly reference Donald Trump or other aspects of the national political climate were less likely to actually run for office than those who used that space to discuss specific policy issues and political opportunities.

Statements of interest collected early in the organization’s existence are cut off at 255 characters, giving us partial responses for roughly one quarter of respondents. Analyses presented below use an additional covariate to identify cut-off documents; all analyses are replicated in the Appendix with these cut-off documents excluded. Five respondents, including two candidates, wrote intelligible responses that did not contain any words that were scalable for analysis. These observations are excluded from analyses based on the statements of interest.

Every respondent who filled out an intake form was invited to participate in a conference call, and every conference call attendee was invited to schedule a one-on-one meeting with a staffer or volunteer to discuss running for office. However, not everyone who ran for office participated in a conference call and/or one-on-one, and some candidates appear to have filed to run prior to filling out the intake form. For this reason, while we can comment on how candidates and non-candidates differed in what they wrote, we do not take statements of interest as necessarily standing causally prior to candidate emergence.

Missingness for race and gender occur early in the data collection period, when these were open-ended fields on the intake form. We matched respondents to the voter file on first name, last name, ZIP code, and age, yielding a match rate of roughly 60%, and inferred remaining missing values for race and gender probabilistically based on respondents’ names, using the R packages {wru} (Imai and Khanna 2016) for inferring race and {gender}(Mullen et al., 2018) for inferring gender. For 218 respondents who did not report an identifiable gender and who’s reported first name did not match to administrative records, we assign the probability of being male as the mean of all other respondents. While we recognize the limitations of reducing our race variable to the probability of being white (Brown, 2014), we make this decision given both the available data and the countervailing limitations of inferring more specific racial categories based on respondents’ names.

References

Anzia, S. F., and Berry, C. R. (2011). The Jackie (and Jill) Robinson Effect: Why do Congresswomen Outperform Congressmen? American Journal of Political Science, 55(3), 478–493.

Atsusaka, Y. (2021). A logical model for Predicting Minority representation: Application to redistricting and Voting Rights cases. American Political Science Review, 115(4), 1210–1225.

Banks, J., and Kiewet, D. R. (1989). Explaining patterns of candidate competition in Congressional Elections. American Journal of Political Science, 33(4), 997–1015.

Bauer, N. M. (2020). The qualifications gap: Why women must be better than men to Win Political Office. Cambridge University Press.

Bernhard, R., Shames, S., and Teele, D. L. (2021). To emerge? Breadwinning, Motherhood, and women’s decisions to run for Office. American Political Science Review, 115(2), 379–394.

Black, G. S. (1972). A theory of political ambition: Career Choices and the role of Structural incentives. American Political Science Review, 66(1), 144–159.

Blais, J., and Pruysers, S. (2017). The power of the Dark side: Personality, the Dark Triad, and political ambition. Personality and Individual Differences, 113, 167–172.

Blais, J., Pruysers, S., and Chen, P. G. (2019). Why do they run? The psychological underpinnings of political ambition. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 52(4), 761–779.

Bonneau, C. W., and Kanthak, K (2020). Stronger together: Political ambition and the presentation of women running for Office. Politics Groups & Identities, 8(3), 576–594.

Brown, N. (2014). Political participation of women of Color: An intersectional analysis. Journal of Women Politics and Policy, 35(4), 315–348.

Carnes, N. (2019). The Cash Ceiling: Why Only the Rich Run for Office -- And What We Can Do about It. Princeton University Press.

Carroll, S. J., and Sanbonmatsu, K. (2013). More women can run: Gender and pathways to the state legislatures. Oxford University Press.

Clifford, S., Kirkland, J. H., and Simas, E. N. (2019). How dispositional Empathy Influences Political Ambition. Journal of Politics, 81(3), 1043–1056.

Conroy, M., and Green, J. (2020). It takes a motive: Communal and agentic Articulated interest and candidate emergence. Political Research Quarterly, 73(4), 942–956.

Constantini, E. (1990). Political women and political ambition: Closing the gap. American Journal of Political Science, 34(3), 741–770.

Crowder-Meyer, M. (2020). Baker, Bus driver, babysitter, candidate? Revealing the Gendered Development of political ambition among ordinary Americans. Political Behavior, 42, 359–384.

Crowder-Meyer, M., and Cooperman, R. (2018). Can’t buy them love: How Party Culture among Donors contributes to the Party gap in women’s representation. Journal of Politics, 80(4), 1211–1224.

Doherty, D., and Dowling, C., and Miller, M. (2019). Do Local Party Chairs think women and minority candidates can Win? Evidence from a Conjoint experiment. Journal of Politics, 81(4), 1282–1297.

Dowe, P. K. F. (2020). Resisting marginalization: Black Women’s Political Ambition and Agency. Political Science, 53(4), 697–702.

Dowe, P. K. F. (2022). The community matters: Finding the source of Radical Imagination of Black Women’s Political Ambition. Journal of Women Politics and Policy, 43(3), 263–278.

Dynes, A. M., Hassell, H. J., and Miles, M. R. (2019). The personality of the political ambitious. Political Behavior, 41(2), 309–336.

Dynes, A. M., Hassell, H. J., Miles, M. R., and Robinson, J. P. (2021). Personality and gendered selection processes in the Political Pipeline. Politics & Gender, 17(1), 53–73.

Fowler, L. L., and McClure, R. D. (1989). Political ambition: Who decides to run for Congress. Yale University Press.

Fox, R. L., and Lawless, J. L. (2004). Entering the Arena? Gender and the decision to run for Office. American Journal of Political Science, 48(2), 264–280.

Fox, R. L., and Lawless, J. L. (2005). To run or not to run for Office: Explaining nascent political ambition. American Journal of Political Science, 49(3), 642–659.

Fulton, S. A. (2012). Running backwards and in high heels: The gendered quality gap and Incumbent Electoral Success. Political Research Quarterly, 65(2), 303–314.

Großer, J., and Palfrey, T. R. (2019). Candidate entry and political polarization: An experimental study. American Political Science Review, 113(1), 209–225.

Gulzar, S. (2020). Who enters Politics and why? Annual Review of Political Science, 24, 253–275.

Hall, A. B. (2019). Who wants to run? How the devaluing of Political Office drives polarization. University of Chicago Press.

Hart, W., Breeden, C. J., Lambert, J., and Kinrade, C. (2022). Who wants to be your Next Political Representative? Relating personality constructs to nascent political ambition. Personality and Individual Differences, 186, 1–6.

Herrick, R., and Thomas, S. (2005). Do term limits make a difference? Ambition and motivations among U.S. state legislators. American Political Research, 33(5), 726–747.

Hobbs, W. Text Scaling for Open-Ended Survey Responses and Social Media Posts. Online, last updated August 2019. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3044864.

Hopkins, D. J. (2018). The increasingly United States. University of Chicago Press.

Imai, K., and Khanna, K. (2016). Improving ecological inference by Predicting Individual Ethnicity from Voter Registration Records. Political Analysis, 24, 263–272.

Juenke, E. G., and Shah, P. (2016). Demand and supply: Racial and ethnic minority candidates in White Districts. Journal of Race Ethnicity and Politics, 1(1), 60–90.

Kirkland, J. H., Simas, E., and Clifford, S. (2022). Perceptions of Party Incongruence and nascent ambition. Political Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09829-8.

Kreitzer, R., and Osborn, T. L. (2019). The emergence and activities of women’s recruiting groups in the U.S. Politics Groups and Identities, 7(4), 842–852.

Lawless, J. L., and Fox, R. L. (2010). It still takes a candidate: Why women don’t run for Office. Cambridge University Press.

Lawless, J., and Fox, R. (2017). Running from Office: Why Young Americans are Turned Off to Politics. Oxford University Press.

Maestas, C. D., Maisel, L. S., and Stone, W. J. (2005). National Party efforts to Recruit State legislators. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 30(2), 277–300.

Maestas, C. D., Fulton, S. A., Maisel, L. S. and Stone, W. J. (2006). When to risk it? Institutions, ambitions, and the decision to run for the US House. American Political Science Review, 100(2), 195–208.

Moncrief, G., Squire, P., and Jewell, M. (2001). Who runs for the Legislature? Prentice Hall.

Mullen, L., Blevins, C., and Schmidt, B. (2018). Gender: Predict Gender from Names using Historical Data. R package version 0.5.2. https://github.com/ropensci/gender.

Ocampo, A. (2018). The wielding influence of political networks: Representation in majority-latino districts. Political Research Quarterly, 7(1), 184–198.

Oliver, S., and Conroy, M. (2018). Tough enough for the job? How Masculinity predicts recruitment of City Councilmembers. American Politics Research, 46(6), 1094–1122.

Oliver, S., and Conroy, M. (2020). Who runs? The masculine advantage in candidate emergence. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Ondercin, H. (2020). The Uneven Geography of Candidate Emergence: How the Expectation of Winning Influences Candidate Emergence. In Good Reasons to Run: Women and Political Candidacy, edited by Shauna L. Shames, Rachel I. Bernhard, Mirya R. Holman, and Dawn Langan Teele. Philadelphia PA: Temple University Press.

Preece, J., and Bogach, O. S. (2015). Does the message Matter? A field experiment on Political Party recruitment. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 2(1), 26–35.

Reckhow, S., Henig, J. R., Jacobsen, R., and Litt, J. A. (2017). Outsiders with deep pockets: The nationalization of local School Board Elections. Urban Affairs Review, 53(5), 783–811.

Riley, G., and Smith, J. (2018). The Trump Effect: Filing Deadlines and the decision to run in the 2016 Congressional Elections. The Forum, 16(2), 193–210.

Rohde, D. W. (1979). Risk-Bearing and Progressive Ambition: The case of members of the House of Representatives. American Journal of Political Science, 23(1), 1–26.

Sanbonmatsu, K. (2015). Electing women of Color: The role of campaign trainings. Journal of Women Politics and Policy, 36(2), 137–160.

Schlesinger, J. A. (1966). Ambition and politics. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Schneider, M. C., and Sweet-Cushman, J. (2020). Pieces of Women’s Political Ambition Puzzle: Changing Perceptions of a Political Career with Campaign Training. In Good Reasons to Run: Women and Political Candidacy, edited by Shames, S. L., Bernhard, R., Holman, M. R. and Teele, D. L. Philadelphia PA: Temple University Press.

Schneider, M. C., Holman, M. R., Diekman, A. B., and McAndrew, T. (2016). Power, conflict, and community: How gendered views of Political Power Influence Women’s ambition. Political Psychology, 37(4), 515–531.

Schwartz, S., and Coppock, A. (2022). What have we learned about gender from candidate choice experiments? A Meta-analysis of 67 Factorial Survey experiments. Journal of Politics, 84(2), 655–668.

Scott, J. S., and Collins, J. (2020). Riled up about running for Office: Examining the impact of emotions on political ambition. Politics Groups & Identities, 8(2), 407–422.

Shah, P. (2014). It takes a black candidate: A supply-side theory of minority representation. Political Research Quarterly, 62(2), 266–279.

Shames, S., Bernhard, R. I., Holman, M., and Teele, D. L. (2020). Good reasons to run: Women and political candidacy. Temple University Press.

Silberman, R. (2015). Gender roles, Work-Life Balance, and running for Office. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 10(2), 123–153.

Silva, A., and Skulley, C. (2019). Always running: Candidate emergence among women of Color over Time. Political Research Quarterly, 72(2), 342–359.

Stone, P. T. (1980). Ambition theory and the black politician. Political Research Quarterly, 33(1), 94–107.

Thomas, S. and Wineinger, C. (2020).Ambition for Office: Women and Policy-making. In Good Reasons to Run: Women and Political Candidacy, edited by Shames, S. L., Bernhard, R., Holman, M. R., and Teele, D. L. Philadelphia PA: Temple University Press.

Thomsen, D. (2017a). Opting out of Congress: Partisan polarization and the decline of moderate candidates. Cambridge University Press.

Thomsen, D., and Swers, S. (2017b). Which women can run? Gender, partisanship, and candidate Donor Networks. Political Research Quarterly, 70(2), 449–463.

Thomsen, D., and King, A. S. (2020). Women’s representation and the Gendered Pipeline to Power. American Political Science Review, 114(4), 989–1000.

Thompson, D., Fiegenbaum, J., Hall, A. and Yoder, J. "Who Becomes a Member of Congress? Evidence from De-Anonymized Census Data." NBER Working Paper No. 226516, December 21, 2022. available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3439166.

Tolley, E. (2019). Who you know: Local Party Presidents and Minority candidate emergence. Electoral Studies, 58, 70–79.

Windett, J. (2014). Differing Paths to the Top: Gender, ambition, and running for Governor. Journal of Women Politics and Policy, 35, 287–314.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Erin Cassese, Will Cubbison, Brett Gall, Michael Neblo, William Minozzi, Monica Schneider, Kelsey Shoub, Aaron Strauss, participants of the University of California Irvine Political Science American Politics Speaker Series and the Harvard Kennedy School American Politics workshop for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. The authors would also like to thank Run for Something for sharing and providing background regarding their data, and Data for Progress for logistical support.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Northeastern University Library

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Jon Green was serving in a volunteer capacity as an advisory board member of Data for Progress while this research was conducted.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Green, J., Conroy, M. & Hammond, C. Something to Run for: Stated Motives as Indicators of Candidate Emergence. Polit Behav 46, 1281–1301 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-023-09872-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-023-09872-z