Abstract

As China’s economy rose to become the second largest in the world, its institutions did not converge with those of other advanced economies as predicted by many Western observers; instead, China developed a distinct form of state-led capitalism. As a result, how multinational enterprises (MNEs) engage with China’s changing institutional context needs to be revisited. To this end, we review 331 papers on MNE strategies and operations in China published in top international business and management journals between 2001 and 2022. We first introduce the path of institutional change and the opportunities and challenges it created for MNEs in China. We focus on six aspects of MNE strategies and operations: market entry, strategic alliances, innovation and knowledge sharing, global value chain strategies, guanxi and relationship management, and non-market strategies. Our analysis of China’s institutional trajectory and of MNE strategies and operations points to three persistent institutional mechanisms of concern for MNEs: challenges to organizational legitimacy, protection of property rights, and the enabling and directing aspect of institutions created by industrial policies. Insights from this analysis point to future research needs on institutional nonlinearities and discontinuities, linkages between inward and outward investments, and geopolitical influences on national institutions.

Plain language summary

Research on multinational enterprises (MNEs – companies that operate in more than one country) in China has unveiled how the country’s unique institutional environment (the legal and regulatory framework within which firms operate) shapes their strategies and operations. China’s emergence as a major economic player has drawn foreign investment, but MNEs often wrestle with challenges like understanding local regulations and safeguarding intellectual property. This article reviews the literature on how MNEs adapt and prosper in China’s changing landscape. It analyses MNEs’ entry strategies, strategic alliances (agreements between two or more parties to pursue a set of agreed-upon objectives), innovation and knowledge sharing, global value chain (GVC – the series of stages in the production process, from design to final product) strategies, relationship management, and non-market strategies (actions outside traditional business practices, such as lobbying or corporate social responsibility). The authors review 331 academic articles on MNE strategies and operations in China published in top international business and management journals between 2001–2022. Key findings include the preference for wholly owned subsidiaries (companies entirely owned by another company) over joint ventures (business entities formed by two or more businesses), the importance of aligning entry locations with MNE strategies, and the difficulties of balancing intellectual property protection with pursuing local innovation. The article also underscores the importance of building trust and managing relationships in the Chinese context, where personal connections (guanxi – a Chinese term referring to networks of influence) can be both a benefit and a drawback. MNEs also need to navigate the complexities of China’s GVCs and adjust their non-market strategies to maintain legitimacy with various stakeholders, including the government. The researchers conclude that while China’s institutional environment poses unique challenges, it also provides opportunities for MNEs that can effectively adapt their strategies. The article’s insights could assist businesses in better understanding the Chinese market and inform policymakers about the impact of institutional changes on foreign investment. Looking ahead, the findings suggest that MNEs’ strategies in China will continue to evolve in response to the country’s ongoing institutional development and global economic and geopolitical changes. This text was initially drafted using artificial intelligence, then reviewed by the author(s) to ensure accuracy.

Résumé

Alors que l’économie chinoise se hissait au deuxième rang mondial, ses institutions n’ont pas convergé avec celles des autres économies avancées, comme l’avaient prédit de nombreux observateurs occidentaux; au contraire, la Chine a développé une forme distincte de capitalisme dirigé par l’État. Par conséquent, la manière dont les entreprises multinationales (Multinational Enterprises – MNEs) s’engagent dans le contexte institutionnel changeant de la Chine doit être réexaminée. À cette fin, nous examinons 331 articles sur les stratégies et les opérations des MNEs en Chine, publiés dans les meilleures revues d’affaires internationales et de gestion entre 2001 et 2022. Nous présentons tout d’abord la trajectoire du changement institutionnel ainsi que les opportunités et les défis qu’il a créés pour les MNEs en Chine. Nous nous focalisons sur six aspects des stratégies et opérations des MNEs : l’entrée sur le marché, les alliances stratégiques, l’innovation et le partage des connaissances, les stratégies de chaîne de valeur mondiale, la gestion des relations et le guanxi, et les stratégies non marchandes. Notre analyse sur la trajectoire institutionnelle de la Chine et sur les stratégies et opérations des MNEs met en évidence trois mécanismes institutionnels persistants qui préoccupent ces dernières: les défis liés à la légitimité organisationnelle, la protection des droits de propriété et l’aspect habilitant et directif des institutions créées par les politiques industrielles. Les renseignements tirés de cette analyse mettent en lumière les futurs besoins de recherche sur les non-linéarités et les discontinuités institutionnelles, les liens entre les investissements entrants et sortants et les influences géopolitiques sur les institutions nationales.

Resumen

Aunque la economía de Chine aumenta hasta convertirse la segunda en el mundo, sus instituciones no convergen con las de otras economías avanzadas como fue predicho por muchos observadores Occidentales; en lugar, China desarrollo una forma particular de capitalismo liderado por el estado. Como resultado, el cómo las empresas multinacionales (MNEs por sus iniciales en inglés) encajan con el cambiante contexto institucional de China necesita ser revisado. Con esta finalidad, revisamos 331 artículos académicos sobre las estrategias y operaciones de las empresas multinacionales en China publicadas en las principales revistas académicas de negocios internacionales y gerencia entre los años 2001 y 2022. Primero introducimos el camino del cambio institucional y las oportunidades y desafíos que creó para las empresas multinacionales en China. Nos centramos en seis aspectos de las estrategias y operaciones de las empresas multinacionales: entrada en el mercado, alianzas estratégicas, innovación e intercambio de conocimientos, estrategias de la cadena de valor global, guanxi y gestión de relaciones, y estrategias no comerciales. Nuestro análisis de la trayectoria institucional de China y de las estrategias y operaciones de las empresas multinacionales apunta a tres mecanismos institucionales persistentes que preocupan a las empresas multinacionales: los desafíos a la legitimidad de la organización, la protección de los derechos de propiedad y el aspecto facilitador y directivo de las instituciones creadas por las políticas industriales. Los aportes de este análisis apuntan a las necesidades futuras de investigación sobre las no linealidades y discontinuidades institucionales, los vínculos entre las inversiones entrantes y salientes, y las influencias geopolíticas en las instituciones nacionales.

Resumo

Quando a economia chinesa se tornou a segunda maior do mundo, suas instituições não convergiram com as de outras economias avançadas, como previsto por muitos observadores ocidentais; em vez disso, a China desenvolveu uma forma distinta de capitalismo guiado pelo Estado. Como resultado, a forma pela qual empresas multinacionais (MNEs) interagem com o mutante contexto institucional da China precisa de ser revista. Para este fim, revisamos 331 artigos sobre estratégias e operações de MNEs na China publicados nos principais periódicos de negócios internacionais e gestão entre 2001 e 2022. Primeiro, apresentamos a passagem de mudança institucional e as oportunidades e desafios que ela criou para MNEs na China. Nós nos concentramos em seis aspectos de estratégias e operações de MNEs: entrada no mercado, alianças estratégicas, inovação e compartilhamento de conhecimento, estratégias de cadeias de valor globais, guanxi e gestão de relacionamento, e estratégias não mercadológicas. Nossa análise da trajetória institucional da China e das estratégias e operações de MNEs aponta para três mecanismos institucionais persistentes que inquietam MNEs: desafios à legitimidade organizacional, proteção de direitos de propriedade e o aspecto facilitador e direcional de instituições criadas por políticas industriais. Insights dessa análise apontam para necessidades futuras de investigação sobre não linearidades e descontinuidades institucionais, ligações entre investimentos para dentro e fora, e influências geopolíticas nas instituições nacionais.

摘要

随着中国经济崛起成为世界第二大经济体, 其制度并没有像许多西方观察家所预测的那样与其它发达经济体的制度趋同; 相反, 中国发展了一种独特的国家主导资本主义。因此, 跨国企业 (MNE) 如何应对中国不断变化的制度环境需要重新审视。为此, 我们回顾了 2001 至 2022 年间在顶级国际商业和管理期刊上发表的 331 篇有关MNE在中国的战略和运营的论文。我们首先介绍了制度变化的道路及其为MNE在中国带来的机遇和挑战。我们重点关注了MNE战略和运营的六个方面: 市场进入、战略联盟、创新和知识共享、全球价值链战略、关系和关系管理以及非市场战略。我们对中国制度发展轨迹以及MNE战略和运营的分析指出了MNE所一直关注的三个制度机制: 对组织合法性的挑战、产权保护以及产业政策所创造制度的赋能和指导作用。从这一分析中得出的洞见表明, 未来需要研究制度的非线性和不连续性、对内和对外投资之间的联系以及地缘政治对国家制度的影响。

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

China’s rise to become the second largest economy in the world has been one of the most significant global mega-trends in the past four decades. China’s labor resources, rising market demand, and growing capacity for innovation have attracted many foreign investors (Duanmu & Lawton, 2021; Zhou, Yim, & Tse, 2005). By the 2010s, many multinational enterprises (MNEs) had incorporated China as a key node in their global strategy to serve the country’s growing consumer demand, leverage its cost-efficient supply chains, and tap into its improving innovation capabilities (Cano-Kollmann, Cantwell, Hannigan, Mudambi, & Song, 2016).

More than 20 years ago, Child and Tse (2001) predicted that China would become a salient international business (IB) hub and follow paths of institutional change toward a free-market economy, driven by the country’s need to increase its integration with Western economies. While some of their predictions came true, some paths hit inflection points driven by world events (e.g., the 2008 global financial crisis) and local events (e.g., changes in China’s leadership), causing changes in direction. Ultimately, China developed its own form of capitalism, often characterized as state-led capitalism, in contrast to the free market and coordinated market economies in, respectively, North America and continental Europe (Witt, Kabbach de Castro, Amaeshi, Mahroum, Bohle, & Saez, 2018).

Contemporary China and its institutions have three particularly noteworthy characteristics. First, China’s central government seems to have gained considerable confidence in its distinct model of institutional development and embarked on an indigenous path of reform. This has been the case for both formal institutions (e.g., legal systems, industry standards) and informal institutions (e.g., business practices, social sentiments, cultural traditions). Second, China’s changing system of institutions continues to present substantial challenges to both MNEs and domestic enterprises. Third, China’s recent developmental path has proven to be strategic, driven by industrial policies selectively supporting its indigenous industries and technologies.

This review is motivated by the apparent paradox of MNEs flocking to China despite their frequent complaints about the obstacles they face in this institutional context. This tension raises intriguing questions for IB scholars seeking to understand how MNEs interact with idiosyncratic national institutions. China’s political economy and business environment differ significantly from those of other emerging economies and are subject to purposeful, non-linear changes. How these idiosyncrasies shape MNE strategies and operations in China merits deeper analysis.

Scholarly analyses of businesses operating under these conditions have generated theoretical insights on interactions between firms and institutions. These insights challenge some previously taken-for-granted assumptions regarding the precondition of market-supporting institutions for economic prosperity; offer higher-level conceptualizations of institutions, their functions, and their components; and highlight the mutual interactions between host-country institutions and MNE operations. Collectively, these insights help to uncover under-researched gaps in IB literature and practice.

Our review analyzes how these institutions have shaped business in China from 2001 to 2022 and highlights three theoretical mechanism by which institutions affect MNEs operating in China: (1) ever-changing challenges to the organizational legitimacy of MNEs affect their ability to operate and their standing with local stakeholders; (2) protection of property rights, especially intellectual property rights, has been improving but continues to affect MNEs’ value creation and appropriation processes; and (3) industrial policies have created institutions that are not only constraining but also enabling and directing (Cardinale, 2018).

Our review offers three key contributions to the IB literature. First, by discussing how China’s institutions evolved from extensive “institutional voids” to the current distinct form of capitalism, we identify indigenous properties of China’s institutions relevant to MNE operations. Second, we review 22 years of research along six salient themes of MNE strategies and operations in IB and management journals, and we offer insights on how MNEs have met the challenges of China’s changing institutions. Third, we identify potential influencing factors that the current literature has missed and offer suggestions for future research. As China continues to rise in global stature and influence, its institutional trajectory and impacts on MNEs will likely remain of keen interest to IB managers and researchers.

China’s institutional evolution

Four decades of reform

China’s reforms can be divided into three phases: market-seeking (1978–1993), market-building (1993–2004), and market-enhancing (post-2004) (Hofman, 2018). Until 1978, China had a centrally planned system that was largely devoid of legitimate market exchanges. It lacked institutions to facilitate market coordination with associated sets of rewards and sanctions to enforce its rules, norms, and belief systems, resulting in institutional voids (Khanna & Palepu, 1997). Instead, in its state-led capitalism, government-related agencies were empowered to shape economic development (Child, 2001).

As the reforms began, China prioritized export-oriented growth that offered opportunities for both domestic and foreign firms (Liedong, Peprah, Amartey, & Rajwani, 2020). Officials who had previously formulated and implemented economic plans by fiat were asked to promote exports and foreign direct investments and became “corporate chiefs” with growth and profit-and-loss responsibilities in their localities, transforming administrative units into “corporations” (Khanna, 2008). However, this high-level institutional change gave rise to a system of fiefs and clans, formed by local government and firms exploiting structural gaps in the economy for private profit (Boisot & Child, 1996). Favoritism, resource misallocation, discrimination against outsiders, and economic waste were common (Peng & Luo, 2000).

Nonetheless, China’s unskilled labor force, inexpensive land and raw materials, and favorable investment terms were irresistible to MNEs in their race towards cost reduction and global value chains (GVCs). Many MNEs worked with local firms and governments to steadily transform China into a “world factory,” with cost-efficient pan-industry supply chains (Zhang, 2006). Although China lacked effective laws to govern market-based exchanges and the capability to enforce laws and contracts, its ruling party’s expansive human resource management system – which effectively goaded officials toward economic growth – served as a powerful (albeit imperfect and corruptive) substitute (McGregor, 2010).

During the second phase of reform, China aimed to build institutions for a market-driven economy. Key milestones included privatization of small and medium-sized state-owned enterprises (SOEs), current account convertibility of the Renminbi, entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO), and recognition of private property in the country’s constitution. The pace of economic liberalization in this phase was rapid, especially during China’s accession to the WTO in 2001. To align the country’s laws and regulations with those of other WTO members, China’s institutions markedly moved toward the Western model of open competition and transparency. However, the dominance of SOEs in certain sectors and the absence of a truly independent judiciary often raised questions about the fairness of competition. In response, MNEs shifted substantial value chain activities to China while adapting to its legal and regulatory limitations.

In the third phase of reform, the Chinese government took an active role in steering the development of its nascent institutions to upgrade the country’s industrial capabilities. These activities include building hard and soft infrastructure (e.g., roads, railways, ports, airports, power plants, communications networks, schools, and innovation systems) and funneling public and private resources to increase the knowledge intensity of value chain activities across many industries (Morck & Yeung, 2014). In this phase, MNEs developed innovation centers as many private intermediaries applied digital technologies to facilitate the functioning of markets. The most prominent of these are the e-commerce and financial platforms set up by Alibaba and Tencent Technologies (Zeng, 2018).

Two approaches to institutional reform

When Deng Xiaoping initiated China’s economic reform in 1978, the approach was cautious and experimental, as captured in the Chinese idiom “crossing the river by feeling the stones” (摸着石头过河). In practice, the approach empowered provincial officials to generate and test new reform measures in their jurisdictions. Once proven successful, these measures were expanded nationwide (Xu, 2011).

In the 2010s, the central government pursued a more uniform approach referred to as “top-level design” (顶层设计), which involved designing reform packages and implementing them nationwide in a top-down fashion (Naughton, 2017). This approach was guided by a national agenda with selective local experimentation. Measures with a high impact on the public are typically debated and put to trial at the local level repeatedly, while measures believed to be broadly popular with minor impact may be adopted with little or no experimentation. In reality, government decision-makers’ unwarranted confidence can cause serious disruptions, such as in the reform of the after-school tutoring industry in 2021 (Liu, 2022).

Institutional reform and political stability

China’s institutional reforms are bounded by political constraints. First, to ensure political stability, the Chinese government chose reform paths that deliver benefits to most of its population and offer compensation to those negatively affected (Rodrik, 2003). Generally, Chinese authorities avoided radical institutional changes that could cause serious economic harm to the general population and potentially trigger political opposition.

Second, despite substantial potential collective benefits, powerful vested interests could stall reforms, often due to the government’s concern about political stability. For example, the housing reform that began in 1988 stalled major developments for more than 20 years due to interventions by landholders (including many farmers), real estate developers, and local governments (Dong, Christensen, & Painter, 2010).

More importantly, there is a binding constraint on China’s institutional changes: no reforms are allowed if they could potentially undermine the rule of the Chinese Communist Party (Zhou, 2020). Some analysts view this constraint as an insurmountable barrier, arguing that it makes significant improvement to China’s core institutions, such as its state-owned enterprises and its judicial system, nearly impossible. Nonetheless, incremental improvements in institutional environments can be seen even under this constraint. For example, in 2003, ownership of SOEs was transferred to the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (SASAC), which reformed SOE governance structures and hence incentives for managers to pursue economic objectives (Wang, Guthrie, & Xiao, 2012). In 2015, the central government set up six circuit courts to oversee the provincial court systems and their judgments to reduce interferences from provincial officials (Botsford, 2016).

Over time, by modifying failed policy initiatives and learning from the West and its more developed Asian neighbors (e.g., Japan, South Korea, and Singapore), China gradually built institutional systems that restrained some corruptive fiefs, improved its capital and banking systems, and diminished regional market barriers. These continuous institutional changes enabled long phases of robust economic growth (DeLisle & Goldstein, 2019).

Industrial policy

China faces new economic challenges, notably the risk of falling into the “middle-income trap,” with its total factor productivity growth decelerating from 3.9% in the latter half of the 2000s to only 0.2% in 2015–2019 (Dollar, Huang, & Yao, 2021). To mitigate this risk, China is pursuing a set of industrial policies that, while opening more sectors to foreign investors, focus resources on select industries for technological catch-up and continue to give SOEs the leading role. These policies are discussed below.

First, China promised to continue its opening policy to further liberalize its FDI regime (Wang, 2022). In 2016, China experimented with “negative lists” of FDI (i.e., automatic approval for projects in industries not on the list). This approach was adopted nationwide in 2020 and left most manufacturing sectors and many trade and financial services open to FDI without specific approval. Correspondingly, the OECD FDI restrictiveness index for China dropped from 0.625 in 1997 to 0.214 in 2020 (OECD, 2022).

Second, Chinese policy makers initially assumed that China could obtain technology from MNEs by offering them market access. Over time, China shifted its industrial policies to prioritize indigenous innovation in critical upstream sectors or major infrastructure investments, such as the state-led high-speed rail project (Gao, 2021). Recently, the “Made in China 2025” program was developed, aiming at world leadership in selected technologies and industries (Li, Van Assche, et al., 2022; Luo & van Assche, 2023). These policies often combine multiple measures. To promote clean energy vehicles, for instance, the government provided subsidies for individual buyers and issued requirements for auto manufacturers to build infrastructure-like charging stations (Gomes, Pauls, & Brink ten, 2023). These policies helped Chinese electric vehicle startups to grow and to enter foreign markets. Thus, the Chinese institutional system has a powerful set of tools for influencing the trajectory of an industry (Kroeber, 2016).

Third, the Chinese government continues to favor SOEs, often at the expense of private firms and MNEs (Lardy, 2019). By many metrics, the share of the private sector has been continuously rising since the 1990s, yet it appears to have peaked by share in investments around 2016 (Posen, 2023) and by stock market value in 2020 (Huang & Véron, 2023). While the Chinese government values market forces’ contributions to economic prosperity, it remains concerned about losing control to private and foreign businesses (Mitter & Johnson, 2021). These concerns seem to have increased, as demonstrated in the rising frequency of government interventions undermining the entrepreneurial spirit in technological and business model innovations (Posen, 2023).

The distinct nature of the institutional framework and its continuous change make engagement with, and adaptation to, the local context a top priority for MNEs operating in China. In our review, we probe the IB literature to explain how MNEs operate under these changing conditions. How have they adjusted their strategies and practices to Chinese institutions, and how have such adjustments changed over time? In the next section, we discuss the methodology of our literature review.

Review methodology

Article search and selection

Our review follows established methodologies (e.g., Luo, Zhang, & Bu, 2019; Meyer, Li, & Schotter, 2020). First, we selected the review period of 2001–2022, which covers 22 years of research on MNE operations in China. Second, we included articles in 21 leading peer-reviewed journals in IB, strategic and general management, and relevant Asia-/China-focused and practice journals (See Online Supplementary Materials for full journal list).

Next, we performed keyword searches in the ABI/INFORM and EBSCO databases for each journal. Keywords included “institution(s)/institutional,” “politic(s)/political,” “government,” “policy/policies,” “law(s)/legal,” “regulation(s),” “contract(s),” “culture/cultural,” “business-government relation(s),” “network(s)/networking,” “practice(s),” and “non-market strategy,” with “China/Chinese” as a second criterion, and “MNE/MNC/multinational” or “foreign firm/subsidiary” or “international joint ventures” as a third criterion. We reviewed each article to ensure that MNE/foreign firm activities and China’s institutions were investigated/discussed. We included:

-

1.

Empirical articles employing quantitative and qualitative methods, as well as non-empirical articles such as review, conceptual, and perspective papers.

-

2.

Articles that focused on China or on multiple countries including China.

-

3.

Articles that utilized data on foreign firms (e.g., MNE subsidiaries) alone, as well as those that also included Chinese firm data (e.g., IJVs or domestic firms as comparison).

-

4.

Articles that included the nation/economy, industry, firm (or subsidiary), and/or employee as the unit of analysis.

We excluded:

-

1.

Articles that only examined Chinese firms’ outward FDI activities.

-

2.

Articles that only discussed Hong Kong, Macau, and/or Taiwan (outside Mainland China).

Journal sample and publishing trends

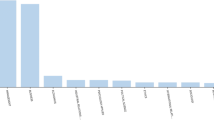

The search produced a final sample of 331 articles from the 21 journals published in the period from 2001 to 2022 (See Online Supplementary Materials for full bibliography). The IB journals produced the greatest number of articles (209). The number of published articles per year on foreign firm activity in China more than doubled from 10.1 articles during 2001–2007 to 20.4 articles during 2016–2022, indicating that the area has grown in research attention and underscoring China’s increasing importance for MNEs in recent decades (Luo et al., 2019).

Methods and theories used

Next, two research assistants were trained to classify and code the articles by methods/type of data used and main theories utilized. Differences were resolved among assistants and coauthors to reach a consensus. Coding output was periodically checked to ensure consistency.

In our sample, 284 articles (85.8%) were empirical papers utilizing quantitative (59.5%), qualitative (18.1%), or mixed methods (7.9%) to examine institutions in China, while 47 articles (14.2%) were non-empirical (commentary/perspective, review, theoretical/conceptual) papers. Due to the broad definition of institutions, our sampled articles employed a wide range of theories, including economic, sociological, IB, organization/management, psychological, and cultural theories, to investigate various aspects of MNE activity. Institutional theory/institution-based view (including institutional economics) was the most commonly used theoretical framework (18.8% of articles), followed by sociological theories (6.9%) and resource-/knowledge-based view (6.3%). Lastly, certain China-specific perspectives were utilized, such as the Confucian and yin–yang perspectives. This variety shows that the complexity of China’s evolving institutional environment requires multiple mainstream theories with both new and indigenous perspectives (Liu, Heugens, Wijen, & Essen van, 2022).

Major themes of research on MNEs in China

To synthesize these articles, we categorized them into major strategic themes, identifying the common themes by the frequency of keywords used in the articles. We consulted well-published experts from different disciplines (IB, strategy, finance, and marketing) to validate the themes. This process produced six major themes that align with relevant MNE strategies and operations (Table 1).

Next, we categorized the articles in our sample based on these themes. The themes each contained an average of 41 articles and had a reasonable threshold number (at least 27 articles). Articles that covered peripheral topics that did not fit into the major themes were counted as miscellaneous (nine articles). We found that most papers adopted a predominant strategy focus in their theoretical framework and dependent measures. However, we note that the six themes are often intertwined and that the insights from a study may involve multiple related themes (e.g., entry strategies can also involve strategic alliances and relationship management).

Review of MNE strategies and operations

We organize our review around six themes: (1) entry strategies, (2) strategic alliances, (3) innovation and knowledge sharing, (4) GVC strategies, (5) relationship management, and (6) non-market strategies. Our review examines how China’s institutional context influences MNEs’ strategic decisions and outcomes.

MNE entry strategies

MNE entry strategies in China have evolved with the changes in the institutional environment. Fifty-seven papers in our database (17.2%) focused on MNEs’ equity modes and entry location as two main dimensions of entry strategies affected by MNE internal factors and formal institutional constraints.

Equity modes

Equity modes determine the governance structures that MNEs establish for their China subsidiaries. In the first phase of reform (1978–1993), the Chinese government invited foreign investors but aimed to retain its influence over business operations in China. Thus, most MNEs’ investments could only be approved as international joint ventures (IJVs), often with SOEs as partners (Duanmu & Lawton, 2021). IB researchers investigated when and how MNEs acquired a higher stake in IJVs (Pan, 1996). Studies also found that a local partner could be useful for MNEs to navigate through China’s complex regulations and relationships, as well as to access local resources and build local capabilities (Yiu & Makino, 2002). Luo (2001) suggests that IJVs were preferred when perceived governmental intervention or environmental uncertainty were high, whereas wholly owned subsidiaries (WOSs) were preferred when intellectual property rights (IPRs) were not well protected. Papyrina (2007) finds that IJVs founded during the early stage of China’s institutional reforms were more likely to survive compared to WOSs from the same period.

In the second phase of China’s reform (1993–2004), especially after China’s entry into the WTO in 2001, more and more sectors were liberalized, allowing MNEs to set up WOSs, for which they showed a clear preference (Guillén, 2003). Some MNEs converted their IJVs into WOSs. Puck, Holtbrügge, and Mohr (2009), investigating why MNEs would buy out their IJVs to create a WOS, found that internal isomorphic pressures and the subsidiaries’ desire to disentangle themselves from the complexities of relationships with local partners were key motives for conversion.

In the post-2004 phase, China further improved its legal and regulatory framework for FDI. Institutional constraints on MNEs’ entry strategies continued to dissipate. The 2019 Foreign Investment Law replaced a complex web of laws and regulations that governed foreign investments for four decades (Zhang, 2022). As more industrial sectors were opened to FDI, MNEs’ attention shifted from the design of ownership structures to operational efficiency and market performance.

Entry locations

China is geographically diverse. IB researchers have investigated sub-national locational advantages and local institutional environments in China. Regional institutional development has been shown to help attract foreign investors (Wang, Roijakkers, & Vanhaverbeke, 2014) and enhance their performance (Luo & Park, 2001). Teng, Huang and Pan (2017) find that MNEs perform well when their strategies align with local institutional environments, while Ma, Delios and Lau (2013) find that MNEs operating in FDI-restricted industries are more likely to choose Beijing over Shanghai as their host-country headquarters location.

Recent studies of micro location decisions focus on social networks and social capital. In a study with exceptionally detailed geographic data, Stallkamp et al. (2018) find that MNEs often locate their first subsidiary in a peripheral city with strong co-ethnic communities and gradually expand into cities through sequences of continuous entries. Menzies, Orr and Paul (2020) note the importance of building social capital locally, including relational, cognitive, and structural components.

Outlook

Over time, MNE entry strategy research has shifted from examining formal institutional barriers to considering informal institutional challenges in China’s state-dominated economy. MNEs worry less about how to enter China and more about how to leverage their competitive advantages and operate profitably. They are likely to view entry into and exit from China as a part of their overall global strategies, along with global innovation networks and global supply chains. Future research on entry strategy should take a holistic approach and examine specific entities as part of MNEs’ global strategies.

Another research frontier lies in China’s service industries, where MNEs find new opportunities among China’s growing middle class of consumers. Investing in service sectors requires MNEs to be more locally embedded so as to overcome cultural norms, local labor management and other informal institutions. As a result, collaboration with local partners becomes an attractive consideration.

Similarly, rapid digitization in China’s economy forces MNEs to rethink and develop new entry strategies to compete effectively in China’s digitizing economy. Their local go-to-market strategy needs to be adopted to the Chinese digital infrastructure; yet it also needs to fit with their operations in other countries. Recent research suggests that national institutions still prevail in this area (Meyer, Fang, Panibratov, Peng, & Gaur, 2023), yet more research is needed to explain how they influence entry strategies in the digital era.

Strategic alliances and acquisitions

The unclear formal institutional framework in the 1990s made strategic alliances a preferred entry mode for foreign investors unfamiliar with the intricacies of doing business in China. Thus, alliances have been a major focus in IB research (43 papers, or 13% of our sample). Through alliances, MNEs leverage inter-firm competences to overcome institutional challenges and operational complexities. In the early 2000s, local partner firms contributed labor management, market knowledge, and relational assets (Lu & Ma, 2008); in recent years, their contributions have become more diverse and complex. Accordingly, governance and managing alliance risks have become paramount to strategy.

Risks, governance, and operations in alliances

Research highlights three risk domains. Institutional risks arise from China’s regulatory (legal and enforcement systems), cognitive (outsider firms), and social (norms and values) institutions. Partnership risks arise from partner firms’ mismatched corporate agendas, organizational fit (Calantone & Zhao, 2001), opportunistic misbehaviors, and IPR violations (Wang & Fulop, 2007). Operational risks include agency hazards from distribution channels, social organizations, and internal staff.

To manage these risks, MNEs need multi-level governance mechanisms. At the top level, equity ownership and board directorship are effective (Haley, 2003). However, partnerships with SOEs are a complex double-edged sword: while they are effective in mitigating regulatory changes (Lu & Yao, 2006), local partners may follow political directives and thus diverge from alliance objectives (Sun, Deng, et al., 2021).

Over time, research has shifted focus from corporate control to how alliances manage synergy (Nippa, Beechler, & Klossek, 2007). Li, Chu, Wang, Zhu, Tang and Chen (2012) find that a collectivistic culture in multi-industry alliances helps these alliances expand their business by leveraging diverse resources and capabilities. Tong, Reuer, Tyler and Zhang (2015) show that when an MNE possesses technological capabilities and unique competences, local Chinese firms rate synergy benefits highly and thus would prefer to form an IJV over being acquired by MNEs.

Studies also examine alliance conflict resolution, legitimacy, and longevity. Gertsen and Søderberg (2011) uncover insights that help resolve alliance conflicts. Mohr, Wang and Goerzen (2016) analyze positive and negative characteristics of multiparty alliances and find that multiparty alliances show diversity, promote balanced strategic views, and gain resource synergy that can overcome institutional challenges, but the coordination complexity increases the likelihood of dissolution, thus reducing their longevity. Fang and Zou (2010) find that local firms’ learning reduces their alliance dependency and longevity. As such, MNEs need to balance the benefits of alliance synergy and dependency concerns.

Moderating effects of the institutional environment

Institutional factors are known to moderate MNE alliance performance. Business networks help MNE staff adapt and overcome regulatory barriers (Bruning, Sonpar, & Wang, 2012). Liao (2015) uncovers clustering effects, finding that MNEs located in privately owned enterprise clusters (which are open and competitive) outperform those in SOE clusters (which are more regulative with restricted markets). Du and Williams (2017) identify negative effects of weak sub-national (i.e., regional) institutions on alliance trust and innovation. Shi, Sun and Peng (2012) find that local firms are attractive partners in “marketized” regions, whereas in less “marketized” regions broker firms are preferred partners. Chan and Du (2021) find that when institutional reforms were slow, unpredictable, or unsynchronized, MNEs seeking local help from embedded organizations mitigated negative reform effects and made alliances more adaptive and locally legitimate.

Outlook

Two trends are emerging in strategic alliance research in China. First, the focus has shifted from forms of alliance (IJV, M&As, and buyouts) to analyzing internal processes in alliances (e.g., CEO succession) and boundary conditions for alliance formation and longevity. Second, the positive and negative effects of China’s multi-level institutions (i.e., central and sub-national) on strategic alliances are being uncovered.

However, it remains unclear why many alliances perform below expectations. While one may attribute this underperformance to institutional challenges, corporate internal processes need further consideration. For example, rigidity of organizational structure and decision making can inhibit needed changes for efficiency and performance. Moreover, few studies have examined the causes and dissolution of alliances, including partner–firm conflict, change of mutual dependency, or goal differences.

MNE innovation and knowledge sharing

China has gradually become a major hub for MNEs’ innovation-related activities, as reflected in 16.9% (56) of our sample papers. Cutting across the three stages of reform are two opposing trends: on the one hand, China’s rising indigenous R&D capabilities have attracted both locally and globally oriented innovation activities (Yip & McKern, 2016), but, on the other hand, China’s weak legal protection and government policies coercing MNEs to transfer technology put MNEs’ proprietary assets at risk (Belderbos, Park, & Carree, 2021). How MNEs balance their innovation pursuits with their efforts to protect and appropriate their outcomes – specifically IPR – continues to attract research attention.

Managing innovation in MNEs

MNEs increasingly invest in local innovation to outcompete local firms in China. Internally, firm orientations, goal setting, and capability balancing are key organizational drivers that impact innovation. Liu and Li (2022) highlight that MNE subsidiaries in China, being dually embedded (in an MNE network and in a host market), are challenged with balancing top-down processes (e.g., exploitative learning with MNE technologies) and bottom-up processes (e.g., exploratory learning).

However, MNEs’ local innovation activities are rife with coordination challenges, knowledge leakages, and appropriation risks (Leung, Tse, & Yim, 2020; Zhou & Li, 2008). Studies confirm the importance of a trustworthy partner providing local market knowledge and access, financial and operational synergies, and resource complementarities (Du & Williams, 2017). Recent studies also find that effective knowledge co-creation depends on factors such as partner compatibility, complementarity, and information verifiability (Chang, Wang, & Bai, 2020).

To mitigate appropriability risks, MNEs utilize WOSs and additional internal strategies. They may control and centralize technology through subsidiaries, rely on trade secrets and internal secrecy rather than patenting, transfer peripheral rather than core technologies to their China subsidiaries, and closely monitor policies and laws (Belderbos et al., 2021; Prud’homme & von Zedtwitz, 2019).

Moderating effects of the institutional environment

China’s evolving institutional environment remains a salient factor in MNE innovation. The legal code regarding IPR has become more refined, and, more recently, enforcement has appeared to gradually improve. However, China’s industrial policies boosting home-grown technology in strategic sectors may have undermined MNEs’ incentives to innovate in China.

Scholars also remain divided in their outlooks. After decades of new laws and IPR enforcement improvements, some argue that China has come more in line with developed economies (Li, 2004) and predict that China will follow the trajectory of developed nations towards better IPR protection when the perceived benefits eventually outweigh costs among domestic stakeholders. Others argue that China’s IPR protection has been inconsistent (Belderbos et al., 2021) due to China’s long-engrained resistance of IPR (Peng, Ahlstrom, Carraher, & Shi, 2017). Brander, Cui and Vertinsky (2017) argue that China’s institutional development and governmental agenda deviate from other countries and that China would only improve its IPR if faced with coordinated pressures from other countries and foreign firms.

China’s industrial policy prioritized indigenous local innovations in selected strategic sectors, exerting direct institutional pressures on MNEs to transfer technologies to local firms (Prud’homme & von Zedtwitz, 2019). MNEs thus face the dilemma of needing to balance IPR protection while seeking legitimacy with the government and local partners. Meanwhile, the rapid growth of high-tech clusters in China offers new opportunities for MNEs to invest in innovations and co-innovations with local firms in China (Prashantham & Bhattacharyya, 2020).

Outlook

The debate over organizational mode choice for IPR and effective innovation remains unsettled. Domestic partner disputes and leakage risks plague IJVs, but the mode can still be effective given certain governance mechanisms and strategic actions. Conversely, WOSs provide advantages in IPR protection but may limit access to embedded local innovation networks.

Patterns of knowledge sharing by MNEs are changing. Whereas in the 1990s technological knowledge typically flowed from MNEs to local firms, the technological gap has significantly narrowed in recent years, with Chinese firms even surpassing foreign firms in certain sectors (Yip & McKern, 2016). MNEs increasingly source local knowledge and collaborate with local stakeholders (customers, suppliers, and distributors). More research is needed to uncover how knowledge flow directionality is evolving as Chinese and foreign firms increasingly compete both within and outside of China. Also, government policy continues to evolve. While many policies disfavor foreign firms, MNEs can benefit from indirect spillovers via local firms.

Global value chain strategies

MNE strategies that incorporate China in their GVC have evolved over the different phases of the country’s economic reform. We found 27 papers (8.2% of our sample) on this topic with three subtopics.

Relationship building

In the early phase of reform, the combination of weak market institutions, severe restrictions on foreign ownership, and weak technological and managerial competencies limited China’s involvement in GVCs to processing and assembly operations. MNEs, notably Hong Kong-based MNEs, were able to build relationships with local officials and utilize kinship ties to attain effective control and limit risks to their IPRs and GVC integrity (Murphree & Breznitz, 2020).

Incorporating China into GVCs

China’s participation in GVCs accelerated after its accession to the WTO, as MNEs took advantage of the more open and transparent regulatory system that allowed them to expand the scope and depth of their supply chain activities in China. However, MNEs faced two issues. The first involves a trade-off between gains from exploiting China’s location-specific advantages and risks from revealing significant proprietary knowledge. Maltz, Carter and Maltz (2011) find that MNEs tend to prioritize supply chain reliability (i.e., quality and on-time delivery) and cost saving over IPR concerns in their choice of GVC locations (i.e., China vs. other countries).

The second issue involves the choice of mechanisms for managing complex and sensitive operations. Internalization offers firmer control, but quasi-internalization based on contracts and relationships provides greater flexibility. Luo, Wang, Zheng and Jayaraman (2012) find that more complex and sensitive MNE activities are associated with increased adoption of tight process integration with affiliates, revealing an important mechanism for quasi-internalization. Dai, Zhou and Xu (2012) show that contracts and relationships are complementary in quasi-internalization: While contract enforcement may be weak in China, detailed contracts still aid in conflict resolution via negotiation by strengthening such mechanisms as the shadow of the future.

Value chain climbing by Chinese firms

In the latest phase of China’s reform, industrial policies are focused on upgrading China’s position in GVCs. Buckley, Strange, Timmer and Vries de (2020) show that mere participation in the fabrication of goods does not raise a country’s share of the GVC income, as advanced economies earn the lion’s share due to their dominance in the knowledge-intensive stages of the value chain. Nonetheless, the rising capabilities of Chinese firms make them likely collaborators, and even competitors, of MNEs. As Chinese firms began climbing the ladder of GVCs, MNEs resorted to internalizing hard-to-imitate stages of the value chain. For example, Usui, Kotabe and Murray (2017) show that Uniqlo was able to leverage its expertise in design, engineering, and marketing in its collaboration with its Chinese suppliers.

Outlook

We detect two intersecting trends in MNEs’ GVC strategies in response to institutional changes in China. First, MNEs’ strategies for retaining effective control over their operations seem to have shifted nonmonotonically with improvements in local firm capabilities and reductions in institutional voids. MNEs initially relied on relationship building in the face of extensive institutional voids, but they adopted internalization via full or majority ownership when allowed in China. As China’s institutional system improves, however, the advantages of quasi-internalization based on contracts and relationships appear to grow, even though MNEs also undertake more complex and more sensitive supply chain activities. This type of nonmonotonic evolution deviates from the pattern of progression envisioned in the traditional internationalization process model (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977), raising interesting questions about the co-evolution of country institutions and GVC mode choice.

Second, MNEs’ GVC strategies in China also respond to institutional developments that affect China’s economic relations with other countries. While MNEs adapt to China’s institutions to gain legitimacy in the country, Chinese governments at various levels also adapt to the demands of MNEs to gain legitimacy in the global economy. Thus, future studies should analyze how MNEs’ GVCs are influenced by not only China’s institutions but also the institutions of the MNEs’ home countries and relevant multilateral and bilateral arrangements such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). These issues are particularly important given the current concerns about supply chain resilience and rising geopolitical tensions (Grosse, Gamso, & Nelson, 2021).

MNE relationship management

Relationship management (RM) is a salient MNE strategy in China as discussed in 11.5% of papers (38 papers) in our sample. Early studies on business in China have delineated the transitive and reciprocal nature of guanxi ties and identified how they can be extended to communities of insiders (Xin & Pearce, 1996). MNEs have recognized guanxi as an effective way to function within China’s institutional voids, utilizing guanxi ties as resources to cope with institutional uncertainty and business risks (Peng & Luo, 2000). These ties can be developed into networks of firms, banks, and government officials. As members share information and reciprocal favors, the ties also protect firms against regulatory demands and policy changes, but these networks can become corruptive (Batjargal, 2007).

More recent studies noted dark-side effects of guanxi and ways that these effects can be mitigated (Gu, Hung, & Tse, 2008). They examined the effectiveness of alternative RM strategies including renqing (人情) – China’s version of empathy (Wang, Siu, & Barnes, 2008) – and inter-firm trust (Zhang, Liu, & Liu, 2015). Studies also investigated strategies to limit the dark side of guanxi (Gao, Ren, & Miao, 2018) and how it is manifested in organizational processes (Genin, Tan, & Song, 2021).

MNEs have corporatized guanxi as a valuable resource, such as in staff appointments, interlocking directorships, and joint venturing with SOEs. By appointing well-connected individuals, MNEs enhance their embeddedness in guanxi networks (Gu et al., 2008). Often, supply-chain reliabilities and adaptive competence improve through access to insider information. Even for venture capitalists, guanxi ties assist in obtaining referrals and funds (Batjargal, 2007). The downside to such ties is that MNEs can become “hostages” of their staff, who leverage guanxi ties for personal gains (Peng & Luo, 2000). Iyer, Sharma and Evanschitzky (2006) warn that guanxi is an “expensive” asset for MNEs that may morally conflict with the professional integrity of MNE managers.

MNEs build inter-firm trust as a legitimate RM strategy by sharing information or joint efforts at the corporate level. Trust enhances B2B co-operation and access to local resources, thereby improving the effectiveness of local supply chains (Yu, Liao, & Lin, 2006) and production operations (Demir & Söderman, 2007). Specifically, inter-firm trust has been shown to enhance buyer–supplier relationships (Yu et al., 2006) and corporate negotiation outcomes (Lee, Yang, & Graham, 2006). Within organizations, Williams and Du (2014) identified the enhancing and joint effects of trust and local learning in MNEs’ innovation performance, and Wang, Jin, Yang and Zhou (2020) show how trust reduces opportunism in IJVs’ radical innovation.

Moderating effects of the institutional environment

The focus of research has shifted from reporting guanxi’s dark-side effects to exploring how guanxi enhances MNEs’ operation processes and performance amidst institutional changes. Karhunen, Kosonen, McCarthy and Puffer (2018) find a positive impact of guanxi on China’s economic development. Peng and Luo (2000) postulate that guanxi may become a proper corporate asset whose functions can be legally and morally bounded. Huang, Shen and Zhang (2020) show that the link between guanxi ties and MNE operations and performance is enhanced by the maturity of China’s institutional environment. Meanwhile, the effects of guanxi have been negatively associated with competitive intensity, supply-chain efficiency, and corporate local experience (Chua, Morris, & Ingram, 2009). Nonetheless, as China’s subnational institutions remain powerful and uneven, guanxi ties in the subnational context will likely remain salient.

Lastly, some MNEs have designed mechanisms to constrain RM’s dark-side or considered adopting inter-firm trust as an alternative RM strategy (Yang & Wang, 2011). Through these effects and corporate self-regulation, MNEs can develop RM strategies without their dark-side effects.

Outlook

Given its cultural roots, we posit that guanxi remains an important feature of doing business in China, though the form and nature of, and the role played by, guanxi and other RM strategies continue to evolve. Several questions remain unanswered. First, how does guanxi operate internally in MNEs (e.g., supervisor–subordinate ties, leadership succession)? While guanxi has been found to enhance team efficiency, citizenship behavior, and innovation (Genin et al., 2021), studies need to assess whether it leads to suppression of internal competition and negatively affect corporate performance and growth.

Second, how can guanxi and other RM strategies be effectively monitored and managed? Gao et al. (2018) postulate that relational gatekeeping can be a necessary tool for MNEs to avoid being exploited by interpersonal networks, yet its reliability and potential side effects (e.g., implied distrust) are insufficiently understood. In China’s complex and dynamic society, we posit that RM is an inevitable strategy for MNEs.

Third, a fuller explanation of the institutional context facilitating or hindering RM needs to weave context-specific concepts (guanxi, renqing, or yin-yang), as critical aspects of informal institutions, into mainstream theories within the hierarchy of China’s national, sub-national, and social institutions (Liu et al., 2022).

Non-market strategies

In the early stage of reform, the institutional arrangements by which firms and government agents interacted in China often appeared opaque to foreign investors (Luo, 2004). Thus, government relations were often left to local JV partners (typically SOEs). With the progression of reform, the channels for non-market activity have become more diverse (Sun, Doh, et al., 2021). The literature (69 papers, or 20.8% of our sample) suggests that the range of non-market strategies has broadened over time, including (1) political ties and activities and (2) stakeholder engagement.

Corporate political activities

Corporate political activity (CPA) is widely believed to be particularly important in China due to the nature of the business-to-government interfaces and the opacity of government decision making (Luo, 2004). The channels and targets used for CPA are strongly influenced by the country’s political and administrative system (Cui, Hu, Li, & Meyer, 2018). In particular, many businesses appoint to corporate boards individuals with ties to political decision-makers, while managers join political decision-making bodies such as the Chinese People’s Congress or the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Committee (e.g., Li, Meyer, Zhang, & Ding, 2018). However, such political ties may be necessary but insufficient for good corporate performance (Peng & Luo, 2000). Zheng, Singh and Chung (2017) find that political ties help firms in China to divest business units through sell-offs, but this effect declines with the institutional development of capital markets. The management of political ties often employs guanxi, as discussed in the previous section.

Beyond personal ties, firms can lobby government decision-makers. Foreign firms often cooperate with others (e.g., in Chambers of Commerce) to jointly lobby local Chinese leaders for policy relief and concessions (Murphree & Breznitz, 2020). However, the dark side of political ties also has been evident in China as corruption has deterred foreign investors and their governmental cooperation (Luo, 2004).

Stakeholder engagement

MNEs increasingly engage with a broad range of stakeholders, using their social and environmental practices to align with broader social agendas in China to indirectly strengthen their legitimacy with political stakeholders. Thus, corporate social activity (CSA) has gained increasing attention. Bai, Chang and Li (2019), studying the impact of both CSA and CPA on market and political legitimacy, find to their surprise that CSA has the stronger impact on both forms of legitimacy. Proactive initiatives helping Chinese communities to address social or environmental issues are appreciated by political actors as long as they do not conflict with the policies or agenda of the CPC.

Corporate philanthropy is also increasingly important. Wang and Qian (2011) and Zhang and Luo (2013) find that corporate philanthropy enhances sociopolitical legitimacy, especially for firms lacking institutional ties of state ownership, and that talking about actions can matter as much as the actions themselves. Marquis and Qian (2014) show that corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting practices have an important signaling role in firms’ relationships with government agencies. However, such a political agenda may backfire if it is too evident. While philanthropic efforts are generally appreciated, Marquis and Qian (2014) also find that CSR activities that embed a profiteering agenda are either rejected or regarded as publicity stunts.

Beyond bilateral ties, MNEs can benefit from participating in wider local business ecosystems. Here, a business ecosystem is understood as “an independent community with different stakeholders, including direct industrial players, government agencies, industry associations, competitors, and customers, who mutually benefit each other and face similar outcomes” (Rong, Wu, Shi, & Guo, 2015, p. 294). Organizational legitimacy is enhanced by embeddedness in such local ecosystems (e.g., Low & Johnston, 2008), as well as the legitimacy of the ecosystem in the wider society. Rong et al.’s (2015) case study describes pathways for foreign investors to nurture their local business ecosystem, identifying three stages: “incubating complementary partners, identifying leader partners, and integrating leader partners” (p. 293).

Outlook

Non-market strategies are important in the institutionally volatile context of China, as they help MNEs to navigate the local environment. Despite economic liberalization, engagement with political actors continues to be important. Indeed, several scholars predict that the importance of corporate political activities will increase due to increasing political tensions, particularly between China and the USA (Li, Shapiro, et al., 2022; Witt, Lewin, Li, & Gaur, 2023).

Non-market strategies have evolved with the institutional framework. We note three main trends. First, partnering with SOEs have declined in importance. Following liberalization, foreign investors can engage directly with market and non-market actors without the need for a local SOE as an intermediary. Second, the range of targets and channels through which foreign investors engage in non-market activities has continuously widened. China continues to be politically centralized, yet with decentralization to provincial and municipal political leaders with respect to interpreting and applying national regulations (Choudhury, Geraghty, & Khanna, 2012; Li, Cui, & Lu, 2014). Thus, MNEs can employ a portfolio of activities to engage a range of actors at multiple levels of the political hierarchy. Third, the importance of CSA as a non-market strategy in China has increased over time, especially after party and government actors urged businesses to participate in the support and rescue operations following the 2008 Sichuan earthquake (Zhang & Luo, 2013). Thus, foreign investors engage in CSA aimed at local audiences, and they have increased their communication about such CSA.

Theoretical insights

Across the six themes of our review, state capitalism operates in the background, directly or indirectly influencing many aspects of MNE strategy and operations. Beyond setting the general rules, state actors shape many of the specific institutions of concern to MNEs. In particular, three theoretical mechanisms emerge by which institutions in China affect the strategies and operations of MNEs: organizational legitimacy in the host society, protection of private property, and the enabling and directing role of institutions (Fig. 1).

Organizational legitimacy

Due to the idiosyncratic and evolving nature of China’s institutions, MNEs face particular challenges to their “organizational legitimacy” (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999) – that is, how they gain the “right” to operate within China’s changing socio-economic and political institutions. In addition to compliance with local laws and regulations, MNEs need to attain legitimacy with consumers, businesses, and other stakeholders in China.

Challenges to MNEs’ legitimacy arise at multiple levels. First, MNEs often face a liability of foreignness, which varies by country-of-origin effects due to differences in public sentiments and perceptions in China (Chaney & Gamble, 2008; Yiu, Wan, Chen, & Tian, 2022) as well as the quality of bilateral political relations (Li, Shapiro, et al., 2022; Stevens, Xie, & Peng, 2016). Second, regional variations within China arise from differences in the progress of institutional reform, social trust (Lu, Song, & Shan, 2018), and historical legacies (Chaney & Gamble, 2008; Zhang, 2022). Third, legitimacy challenges vary across industries due to health and safety sensitivity, as well as to national security (Peng, Liu, & Lu, 2021; Stevens et al., 2016).

How can MNEs attain organizational legitimacy in China? On this question, the China-focused management literature departs significantly from mainstream institutional theory. A core proposition of institutional theory is that organizations enhance their legitimacy through isomorphic strategies that resemble those of incumbents in the field (Child & Tsai, 2005). However, isomorphic strategies are unlikely to work for MNEs in China, because MNEs risk losing their distinctive competitive edge when they become more like local firms (Yildiz & Fey, 2012). Ultimately, a key condition that legitimizes an MNE’s business is the ability to offer something that local firms cannot. Moreover, some common practices of local firms, such as gift giving, may conflict with MNEs’ home country laws. Thus, MNEs need to develop localized strategies and practices that enhance their legitimacy, performance, and growth. In turn, their corporate political activities also provide feedback to Chinese policy makers in their institutional reform that can further facilitate the legitimacy of the MNEs.

Protection of property rights

In international expansion, MNEs combine their own resources with local resources to create value (Pitelis & Verbeke, 2007). These processes are critically dependent on external institutions, notably the protection of property rights. Historically, institutional protection of property rights has been weak in China (Peng et al., 2017). Despite substantial legislative advances, law enforcement and inherited cultural attitudes still do not allow for effective protection of IPR (Belderbos et al., 2021). Therefore, questions of value creation and appropriation under imperfect property rights constitute a common theme in the management literature focusing on China.

A rising challenge to value appropriation stems from the increased competences of local firms, as increased technological competences enhance their absorptive capacity and, hence, their ability to utilize knowledge to which they are exposed for their own ends. However, in light of the increased technological competences of local competitors, MNEs have to deploy more advanced technologies to remain competitive.

Fundamentally, value creation in Chinese subsidiary depends on international knowledge sharing, yet the transfer of knowledge-based assets to an operation in China can result in a loss of control over such assets. This scenario leads to two theoretical questions. First, how do MNEs handle the trade-offs between the risk of IPR loss and the potential gains from combining their resources with the location-specific resources in China? Recent studies suggest that MNEs are willing to accept IPR risks when the technology in question is peripheral or involves only components of a complex product, but they shy away from risking their core or architectural technology (Chi & Zhao, 2014; Usui et al., 2017).

Second, the theory of the firm suggests that MNEs would respond to appropriation risks by internalizing transactions in knowledge-intensive assets; however, what happens if this is not feasible or entails a high cost (e.g., loss of flexibility)? The literature we reviewed suggests that some MNEs have adopted various quasi-internalization mechanisms, such as combining contractual and relationship governance (Dai et al., 2012), choosing partners with compatible corporate agendas and organizational fit (Calantone & Zhao, 2001; Chang, et al., 2020), and fostering internal linkages and compartmentalization within the global MNE (Belderbos et al., 2021; Leung et al., 2020; Prud’homme & Zedtwitz, 2019).

Enabling and directing institutions

Studies of institutions in emerging economies traditionally focus on institutional voids – that is, gaps in market supporting institutions (Khanna & Palepu, 1997). However, studies on business in China often point to the enabling or directing nature of institutions. In particular, governments at multiple levels direct businesses, including MNEs, toward business activities they consider desirable, such as technological and economic development in certain industries or geographic areas. These enabling institutions aim at attracting foreign investment to sectors deemed strategic (Liu, 2022; Morck & Yeung, 2014). Recently, the Chinese government designed institutions specifically to enable the technological catch-up of domestic firms or the participation of MNEs in Chinese-led outward investment projects.

Enabling institutions also exist to promote regional growth. For example, the Chinese government initiated a comprehensive program to support the development of the western interior with infrastructure projects, industrial parks, and state subsidies (Deng, Lu, & Chen, 2015). Thus, the government encourages forms of MNE engagement that serve the government’s objectives (particularly transfer of knowledge) but discourages activities that it perceives as hindering catch-up by local firms.

Contrary to the conventional conceptualization of institutional voids that deter effective market functioning of MNEs in emerging economies, our review suggests that institutions in China can also be analyzed from the enabling and directing perspectives. China’s formal institutions are a mix of constraining and enabling institutions that aim at promoting economic growth and technological catch-up while securing the overarching control of the party over the economy and polity.

Avenues for future research

Many aspects of the interactions between institutions and foreign investment merit further investigation. Table 2 summarizes the key findings and research gaps for the six themes. Three major changes in China’s business environment also raise new questions: institutional nonlinearities and discontinuities, inward–outward linkages, and geopolitical dynamics.

Institutional nonlinearities and discontinuities

Over the four decades since China’s initial opening to FDI, the institutional framework appears to have continuously moved in the direction of market liberalization, transparency and a more level playing field. However, more fine-grained analysis provides a mixed picture, as some changes were discontinuous and disruptive at the time, while other changes paired tighter regulation in one sphere with more openness in another sphere. As the reviewed studies typically have a cross-sectional design, the longitudinal image emerges from the aggregation of temporally bound evidence. A better understanding of institutional change thus calls for more fine-grained longitudinal work. Multi-period study designs may be able to shed further light on how China’s changing institutions affect MNEs, helping to establish the historical boundedness of many of the literature’s empirical insights. Future research thus should prioritize longitudinal or historical perspectives to develop a better understanding of how institutions co-evolve with market and non-market strategies.

In particular, the interplay between institutional change in related spheres merits further exploration. For example, MNEs face trade-offs between value creation and appropriation that evolve along with changes to institutions related to property rights. The dynamic interactions between IPR protection, firm capacity upgrade, and MNE strategy for managing value creation and appropriation thus merit further investigation. Similarly, how IJVs and other strategic alliances dynamically cope with China’s changing institutions is a topic of both academic and practical value.

Studies of institutional discontinuities may explore the digital economy, which has experienced spectacular growth in China, subject to its own set of institutional changes over time. Foreign investors using digital platforms as means of market entry thus need to adapt to not only the regulatory institutions of the country but also the specific platform-based ecosystem (Li, Chen, Mao, & Liao, 2019; Rong, Kang, & Williamson, 2022). Indeed, the effective integration of online and offline operations may be the most important success factor in contemporary consumer markets in China (Qi, Chang, Hu, & Li, 2020). In the digital economy, the relevant institutions are often determined by dominant players that control key platforms (e.g., T-Mall, operated by Alibaba), who enable or constrain the accessibility of customers and complementors and manage related logistics and payment ecosystems (Leong, Pan, & Cui, 2016). Such platform-developed rules accommodate the government’s expectations for rules regarding, for example, content monitoring, privacy, and data management (Stevens et al., 2016). These institutions in the digital economy thus diverge from those in Western economies. How institutions shaped by government policy interact with institutions created by platform owners, and how MNEs can operate within this interplay, are interesting research questions.

Inward–outward linkages

China’s policy makers aim to establish inward–outward linkages between foreign businesses in China and Chinese firms investing overseas. The interaction between foreign and local firms creates knowledge and technology spillovers that strengthen local firms (Hertenstein, Sutherland, & Anderson, 2017; Prashantham & Bhattacharyya, 2020; Wang et al., 2014). As Chinese firms gain competitive advantages, some of them have started to invest overseas and to compete effectively outside China. The mechanisms by which local firms benefit from the presence of foreign MNEs and the strategies MNEs use to engage with their internationalizing local partners merit further research.

Following the inward–outward mindset, Chinese government launched the BRI in 2013, which was designed to accelerate outward investment of strategically important Chinese firms (Li, Van Assche, et al., 2022). The BRI supports co-development plans extending from China to Asian, Middle Eastern, African, and even Central and South American countries. Many BRI projects are in principle open to participation by non-Chinese MNEs. This raises interesting research questions on how non-Chinese MNEs can join BRI projects and how such engagement may help them to strengthen their positions and performance in China, as well as in other countries.

External political relations and geopolitics

In recent years, China has experienced significant geopolitical tensions with the United States. Rising geopolitical tensions and “techno-nationalism” in China and the US create risks for MNEs who may find their operations, especially their knowledge management, obstructed and their legitimacy challenged. Foreign firms are thus increasingly concerned about being strategically targeted (Luo & van Assche, 2023). How MNEs navigate in this institutional environment calls for future research.

Some scholars predict a deglobalization or bifurcation of the global economy (Teece, 2022; Witt et al., 2023). Recent industrial policy initiatives in China and the US appear to mutually reinforce policymakers’ perception that the two nations need to protect their own industries and, thus, to intervene in foreign trade and investment. The dynamics of this intergovernmental tit-for-tat and the coping strategies MNEs employ, especially in terms of how they protect their IP, merit further research attention.

At the national level, the recently increased interest in industrial policies in countries that used to profess a strong distaste for them – as evidenced by the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS and Science Act in the US (Luo & van Assche, 2023) – seems to suggest that China’s apparent success using industrial policy to upgrade the capabilities of Chinese firms is altering the institutions of other countries. Perhaps this trend reflects a form of interactive or reverse isomorphism. Thus, scholars using institutional perspectives should broaden their scope of study to examine how institutional changes in different countries interact and how such interactions affect MNE strategies. At the firm level, increasing political obstacles induce some MNEs to relocate to other parts of the world, such as Vietnam. So far, few studies have examined MNE exit in response to adverse political change, political sanctions, and other political barriers (Meyer et al., 2023).

Conclusion

Over the past three decades, MNEs operating in China have faced a continuously changing institutional environment. Some issues remain highly relevant to MNE managers and researchers, such as challenges to organizational legitimacy, ineffective property rights protection, and directing aspects of institutions created by industrial policy. Our review of MNEs operating in China highlights the ongoing pivotal role of institutions as a key contextual factor for MNE strategies. The trajectory of institutional change over the past three decades has impacted MNEs across several dimensions.

First, China’s recent formal institutional changes have been largely purposive, though not always effectively managed nor publicly endorsed. Recent changes reflect China’s aspiration to become a politically independent player on the global stage. This mission-based model of China’s industrial policy differs from those of advanced nations in both objectives and implementation. Therefore, China’s path of institutional development has been distinct and, thus, has deviated from the common prediction of convergence with Western models of capitalism.

Second, our review allows us to postulate some insights into China’s future institutional trajectories. While some of China’s formal institutions are evolving along a path that differs from the free-market model, the Chinese government is maintaining a relatively open attitude toward engaging with global businesses. However, internally, a restricted system of institutions with low transparency governs both domestic and foreign-owned firms. These tensions will continue to challenge MNEs operating in China, especially those aiming to benefit from “Made in China 2025” and BRI projects.

Finally, tracing the country’s past trajectory, we posit that China’s internal factors (e.g., leadership and national aspiration) and external factors (e.g., global stature and geopolitics) will continue to generate two cross-currents that will shape its future institutional change. While global standards in design, content, and implementation dominate in many spheres, indigenous content is increasingly important (Liu et al., 2022). Increased legitimization demands thus fall on MNEs.

References

Bai, X., Chang, J., & Li, J. J. (2019). How do international joint ventures build legitimacy effectively in emerging economies? CSR, political ties, or both? Management International Review, 59(3), 387–412.

Batjargal, B. (2007). Network triads: Transitivity, referral and venture capital decisions in China and Russia. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(6), 998–1012.

Belderbos, R., Park, J., & Carree, M. (2021). Do R&D investments in weak IPR countries destroy market value? The role of internal linkages. Strategic Management Journal, 42(8), 1401–1431.

Boisot, M., & Child, J. (1996). From fiefs to clans and network capitalism: Explaining China’s emerging economic order. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41(4), 600–628.

Botsford, P. (2016). China’s judicial reforms are no revolution. IBA Global Insight.