Abstract

Recent studies of contested elections in the House have pointed to party electoral goals as motivating their resolution in Congress. However, little systematic research has been conducted on why such elections were contested to begin with. Using historical data and new statistical analysis of such elections from the late nineteenth century, I find that, in contrast to the claims of some scholars, political principles as well as electoral objectives mattered to parties seeking to contest elections. In addition, election conditions, particularly the means by which southern white Democrats attempted to repress the vote of southern blacks, independently influenced the probability of contestation. This finding has implications for our understanding of Republican Party strategies and electoral conditions in the South during the period, and the origins of contested elections at other times in American history.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Jeffery A. Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases in the House of Representatives, 1789–2002,” Studies in American Political Development 18 (Fall 2004): 112–35 (113); see also Nelson W. Polsby, “The Institutionalization of the U.S. House of Representatives,” American Political Science Review 62 (1968): 144–68; and O. O. Stealey, Twenty Years in the Press Gallery (New York, NY: Publishers Printing Company, 1906), 147.

Polsby, “The Institutionalization of the U.S. House of Representatives”; Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases,” 125–26.

Note that a contested case could include more than one contested congressional seat; Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases,” 115. As with Jenkins’ dataset, contested cases were obtained from congressional reports and studies of contested elections, as well as the Congressional Record index. See John Thomas Dempsey, “Control by Congress Over the Seating and Disciplining of Members” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan, 1956); Merrill Moores, Digest of Contested Election Cases in the House of Representatives, 1901–1917 (U.S. House of Representatives, Doc. 2052, 1917); Chester H. Rowell, An Historical and Legal Digest of Contested Elections in the House of Representatives from 1789 to 1901 (U.S. House of Representatives, Misc. Doc. 510, 1901); and Angie Welborn, House Contested Election Cases, 1933 to 2000 (New York, NY: Novinka Books, 2003). In contrast to Jenkins, I excluded cases that were not evaluated by a congressional committee, in order to eliminate frivolous or unmerited challenges, and included territorial contests. For details on the institutional process by which contested election cases were resolved in the House, see Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases,” 113–15.

See Table 2 in Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases,” 117.

These include the so-called New Jersey “Broad Seal Case” in the 26th Congress (1839–1841), Smith v. Jackson in West Virginia in the 51st Congress (1889–1891), and Kunz v. Granata from the 72nd Congress (1931–1933); and Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases,” 118–20.

See for example Darrell v. Bailey in the 40th Congress (1867–1869); Chalmers v. Morgan in the 50th Congress (1887–1889); and Rowell, An Historical and Legal Digest, 246, 457.

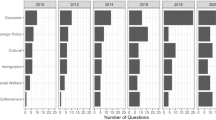

In the first 20 congresses (1789–1829), 60 seats were contested, or fewer than 10 percent of all such elections. For a chart of all contested cases since 1789, see Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases,” 116.

Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases,” 115.

Dempsey, “Control by Congress,” 45.

Committee on Elections No. 1, “Proceedings in Cases of Contested Elections of Members of the House of Representatives” (U.S. House of Representatives, Report 1595, 1923), 3; Dawes, “The Mode of Procedure in Cases of Contested Elections,” 65; Dempsey, “Control by Congress,” 44–45; Polsby, “The Institutionalization of the U.S. House of Representatives”; C. H. Rammelkamp, “Contested Congressional Elections,” Political Science Quarterly 20 (1905): 421–42.

Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases,” 125–26.

Richard Bensel, Sectionalism and American Political Development, 1880–1980 (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1984), 87. For more on the Republican need for southern seats, see Richard M. Valelly, The Two Reconstructions: The Struggle for Black Enfranchisement (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2004).

Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases,” 126–27; quote at 128.

Bensel, Sectionalism and American Political Development; Dempsey, Control by Congress; Rammelkamp, “Contested Congressional Elections,” 431–32.

Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases,” 113, 128–30, 133–34.

Although Jenkins examines cases through 1908, I include 1910 because it includes the last significant uptick in the number of cases, and allows for greater variation in party control of Congress.

I define the “South” here as the eleven states that were members of the Confederacy during the Civil War: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia.

Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases,” 130.

See for example Allen Johnston Going, Bourbon Democracy in Alabama, 1874–1890 (University, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1951), and the cases of Darrell v. Bailey and Chalmers v. Morgan, mentioned in an earlier footnote.

Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, Candidate and Constituency Statistics of Elections in the United States, 1788–1990 [Computer file], 5th edition (Ann Arbor, MI, 1994).

The rare events logit model was implemented using the ReLogit function in Stata ver. 8.2. Michael Tomz, Gary King, and Langche Zeng, “ReLogit: Rare Events Logistic Regression,” Journal of Statistical Software 8 (2003): 137–63. The dataset may also suffer from temporal dependence, which could affect the estimates of standard errors in the regression, though the variables measuring congressional factors are unique to virtually every Congress and are thus highly collinear with fixed effects variables. Nathaniel Beck, Jonathan Katz, and Richard Tucker, “Taking Time Seriously: Time-Series-Cross-Section Analysis with a Binary Dependent Variable,” American Journal of Political Science 42 (1998): 1260–88.

Congress enacted minor amendments to the 1851 Act in 1873, 1879, and 1887 to alter time limitations, particular procedural rules, and limits on reimbursement of contestants. The nineteenth-century practice of allowing the reimbursement of the expenses of contestants and contestees could have encouraged cases, but it is not clear when the practice was discontinued. Rammelkamp, “Contested Congressional Elections,” 426–27, 434.

Allen and Allen, for example, assert that election fraud was not as prevalent as reformers at the time claimed, while Argersinger disagrees. Howard W. Allen and Kay Warren Allen, “Vote Fraud and Data Validity,” in Analyzing Electoral History: A Guide to the Study of American Voter Behavior, ed. Jerome M. Clubb, William H. Flanigan, and Nancy H. Zingale (Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, 1981); Peter H. Argersinger, “New Perspectives on Election Fraud in the Gilded Age,” Political Science Quarterly 100 (1985–86): 669–87.

Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases,” 135 n86. Unlike Jenkins, I do not assert that the Australian ballot eliminated fraud entirely; indeed, fraud could still be committed with the ballot, as was often alleged with respect to elections in urban areas in the early 1900s. See for example Tracy A. Campbell, “Machine Politics, Police Corruption, and the Persistence of Vote Fraud: The Case of the Louisville, Kentucky, Election of 1905,” The Journal of Policy History 15 (2003), 269–300; and Earl R. Sikes, State and Federal Corrupt-Practices Legislation (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1928), 62–63.

Allen and Allen, “Vote Fraud and Data Validity,” 177–78; Bensel, Sectionalism and American Political Development; C. Vann Woodward, Origins of the New South, 1877–1913 (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1951), 326.

Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (New York, NY: Harper and Row, 1988); Valelly, The Two Reconstructions.

Since district-level census data on black population exist only at the county level, it is unavailable for districts that comprise subsets of counties, which includes a number of northern congressional districts. Thus, the data are used for a regression on southern House elections only.

Georgia had effectively disfranchised most black voters through the poll tax, adopted in 1877; constitutional disfranchisement was not adopted in that state until 1908. Gerrymandering was also employed in some cases to reduce the black vote (such as in Mississippi, Tennessee, and South Carolina). Unlike disfranchisement, however, gerrymandering was less efficient and could not guarantee the permanent elimination of black voters at all levels of government that southern Democrats ultimately sought. See Foner, Reconstruction, 590; J. Morgan Kousser, “The Voting Rights Act and the Two Reconstructions,” in Controversies in Minority Voting, ed. Bernard Grofman and Chandler Davidson (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1992), 144–45; and Michael Perman, Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888–1908 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 13, 281, 293.

Jenkins also suggests that disfranchisement was more important in preventing a re-emergence of cases in the 1910s than in causing its disappearance in the 1890s. Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases,” 135, n86.

Table 12 from Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases,” 133. Not all southern states saw a major decline after disfranchisement. In Georgia, cases from 1892 and 1894 were based on claims of bribery, intimidation, and/or fraud—not disfranchisement laws—while three pairs of later cases involved the same individual in the same district (68th and 69th, 80th and 82nd, and 90th and 91st Congresses). Rowell, An Historical and Legal Digest, 489–91, 510, 513. Two other states, Mississippi and South Carolina, also brought a significant number of cases to Congress, illustrating both that disfranchisement did not uniformly eliminate contestation and that Republican Party leaders could not stop persistent southern Republicans from challenging disfranchisment. See below.

Joel Williamson, A Rage for Order (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1986).

Jenkins uses several alternative measures of partisanship, including whether the majority party overturned an election to seat its own candidate, if a committee was “rolled” on the floor by its party, or if a recorded floor vote on a contested election was highly partisan. I do not use these measures, because some of them would have been less visible to the public and would therefore be less likely to influence would-be contestants’ behavior. Also, duplicate contests for the same seat (such as special elections) were not merged together, since they could have been resolved differently, and same-party and abandoned cases were not included.

Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases,” 120–21.

Bensel, Sectionalism and American Political Development; Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases,” 132; Committee on Elections, “Proceedings in Cases of Contested Elections of Members of the House of Representatives,” 2.

The variable ranges from a theoretical maximum of 0 (the natural log of 1) to −0.69 (the natural log of 0.5, or half of all seats), though it could be smaller than −0.69 in practice. This occurred in the 19th, 25th, 31st, 34th–36th, and 65th Congresses. This is the predictor most likely to be endogenous in the regression, since the number of majority party seats might conceivably affect the supply of contested elections. While not a problem in itself, adding an interaction effect between majority party size and whether the election winner was of the opposite party does introduce multicollinearity, since majority party size is inversely proportional to the number of elections won by the opposite party.

Bensel, Sectionalism and American Political Development; Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases.”

Because very few congressional seats in the South were open seats, this variable is omitted for the regression analysis for southern districts.

The ReLogit model, which emphasizes bias reduction over fit, does not provide a goodness of fit statistic. Using logit instead provides a pseudo-R2 statistic ranging from 0.22 to 0.24.

A χ2 test comparing the distribution of southern Republican seats by black population under Democratic versus Republican majorities shows a statistically significant difference (Pearson χ2=21.03, P=0.004).

Jenkins notes that the Republicans also gained many seats via contestation in the 54th Congress (1895–1897), but the party had already won a large majority of seats in the 1894 elections. Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases,” 127.

Although some Republicans believed that southern vote fraud had sometimes robbed them of absolute majorities, they could not rectify this by reversing election outcomes while in the minority. Xi Wang, The Trial of Democracy (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1997), 222–23; Richard M. Valelly, “Partisan Entrepreneurship and Policy Windows: George Frisbie Hoar and the 1890 Federal Elections Bill,” in Formative Acts, ed. Stephen Skowronek and Matthew Glassman (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, forthcoming). This finding does not preclude the possibility that House Republicans wanted to strengthen their position in southern congressional districts specifically. See below.

As Republicans cemented their control over northern districts, marginality in elections from those districts increased as well. Nationally, winning House candidates won election with an average margin of 15–20 percent through 1896, while the average margin increased every year thereafter, reaching a high of 46 percent three decades later.

Stanley P. Hirshson, Farewell to the Bloody Shirt (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1962); Valelly, The Two Reconstructions.

Hirshson, Farewell to the Bloody Shirt, 26, 28, 79–80, 99–107, 143, 162–68; Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases,” 129; Alexander Keyssar, The Right to Vote (New York, NY: Perseus, 2000), 108.

Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases,” 133–34. Southern Republican opposition appeared, for example, during House debate of the so-called Force Bill in 1890. Wang, The Trial of Democracy, 239–40.

Valelly, The Two Reconstructions, 64–65.

Valelly, The Two Reconstructions, 51.

Foner, Reconstruction, 456; Valelly, “Partisan Entrepreneurship and Policy Windows”; Wang, The Trial of Democracy, 163.

This is similar to the “mixture of partisan and principled reasons” the Republican Party had for federal monitoring and enforcement of election laws, particularly in the South, during the decades after the Civil War. Keyssar, The Right to Vote, 109.

Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases,” 132–34.

A series of federal court rulings also limited the powers of Congress over southern elections. Hirshson, Farewell to the Bloody Shirt; Kousser, “The Voting Rights Act and the Two Reconstructions,” 29–33; Michael W. McConnell, “The Forgotten Constitutional Moment,” Constitutional Commentary 11 (1994): 115–44; Perman, Struggle for Mastery; Rogers Smith, Civic Ideals: Conflicting Visions of Citizenship in U.S. History (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997), 383–85; Wang, The Trial of Democracy, 259; Woodward, Origins of the New South, 325–26.

Perman, Struggle for Mastery, 94. The 1882 registration law had led to at least one previous election challenge from South Carolina when Republicans controlled the House; see footnote below.

This case was actually decided after Johnston v. Stokes, and Republicans voted almost unanimously on the floor to seat the Republican contestant. However, the contestant's case was partially based on a registration law that applied only to parts of the district (the city of Charleston), in addition to allegations of fraud specific to that election (Congressional Record, 3 June 1896, 6073). Of the 52 Republicans who had voted in Johnston v. Stokes to vacate the seat, 30 voted to seat the Republican in Murray v. Elliott, while the other 22 did not vote.

Rowell, An Historical and Legal Digest, 530, 541–46.

Congressional Record, 5756–57, 5770, 5908, 5910.

Congressional Record, 5875, 5913.

Congressional Record, 5900–01. The Republican dissenters in Johnston v. Stokes argued that prior cases heard by the House had accepted lists of voter intent. The House had heard one previous case from South Carolina based on its registration law (Miller v. Elliott) in the 51st Congress (1889–1891), but while a majority of elections committee members ruled in that case that the state's registration law was unconstitutional, it found sufficient evidence of illegal activities to reward the black Republican contestant the seat on those grounds alone. Rowell, An Historical and Legal Digest, 461–64, 533.

“An Election Case Shelved,” New York Times, 30 May 1896, 3; “Divided Over the Contest,” Washington Post, 30 May 1896, 4.

While this was not the first time the Republicans had divided on a floor vote over a contested election, it was the first in which the case was based on election laws and secondary evidence of voter intent, rather than evidence of fraud or violence.

This implies that House Republicans began shifting away from using contested elections two years before Jenkins alleges; Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases,” 129. Voting patterns suggest that election committee members recruited fellow state delegations to vote with them: most legislators from Massachusetts voted against the Republican challenger, while Indiana and Michigan Republicans were strongly supportive of seating him. A simple logit regression analysis of the second vote, to deny the seat to the Republican, suggests that—controlling for ideology (as measured by DW-NOMINATE scores), region, and term in office—Republicans ideologically closer to Democrats were more likely to oppose the Republican challenger, while those from New England states were less likely to do so.

In the case of Patterson v. Carmack in the 55th Congress (1897–1899), the Republican-controlled elections committee awarded a Tennessee seat to the contestant (a Democrat endorsed by the Republican Party), primarily on the basis of fraud and irregular election-day activity, but poor floor attendance and the defection of a few Republicans allowed the Democrats to pass a measure awarding the seat to the incumbent Democrat. Rowell, An Historical and Legal Digest, 574–77.

Perman, A Struggle for Mastery, 224–44. A few brave (or at least persistent) southern Republicans did not give up. In Houston v. Broocks (59th Congress, 1905–1907), the contestant argued that the Texas poll tax deprived him of likely supporters, but the elections committee—fearing it would have to unseat all Texas incumbents as a consequence—ruled against him. In Warmuth v. Estopinal, the contestant challenged the 1908 congressional election results based on the constitutionality of Louisiana's white primary. He was rebuffed by the House election committee, which based its decision in part on Dantzler v. Lever. Moores, Digest of Contested Election Cases, 33, 41–42.

Donald Bruce Johnson, National Party Platforms, 1840–1976 (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1978); Valelly, The Two Reconstructions, 134–39.

Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1970), 226–38; Rowell, An Historical and Legal Digest, 156–59, 168–70.

On St. Louis election improprieties, for example, see James Neal Primm, Lion of the Valley, 2nd edition (Boulder, CO: Pruett Publishing, 1990). Patterns of election fraud and electoral competition varied over time across cities. Reform movements in New York, for example, were arguably a greater challenge to the Tammany Democratic machine in the 1890s than in the 1900s through the 1920s, and election fraud was probably less frequent during this later period as a result. Charles Garrett, The LaGuardia Years (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1961).

This low number is likely due to a combination of factors. Improvements in election administration, such as the use of mechanical lever ballot machines and the deployment of professional election workers, may have discouraged fraud. Changes in congressional rules and norms may have further dampened the enthusiasm to challenge election results. Congressional Record, 10 January 1941, 101; Dempsey, Control By Congress.

Committee on House Oversight, Dismissing the Election Contest Against Loretta Sanchez (U.S. House of Representatives, Report 105–416, 1998); Congressional Quarterly, Guide to Congress, 5th edition (Washington, D.C.: CQ Press, 2000), 836–37.

Bensel, Sectionalism and American Political Development.

Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases,” 115, 119.

Jenkins, “Partisanship and Contested Election Cases.” This and other scholarship suggests that institutionalization theory may be less useful in explaining the development of Congress. See for example, Jonathan N. Katz and Brian R. Sala, “Careerism, Committee Assignments, and the Electoral Connection,”American Political Science Review 90 (1996): 21–33; and Joseph Cooper and David W. Brady, “Toward a Diachronic Analysis of Congress,” American Political Science Review 75 (1981): 988–1006.

Desmond S. King and Rogers M. Smith, “Racial Orders in American Political Development,” American Political Science Review 99 (2005), 75–92.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

The author thanks Richard Bensel, Donald Green, Michael Heaney, Jeffrey Jenkins, Matthew McDonald, David Mayhew, Naomi Murakawa, Wendy Schiller, Colleen Shogan, Rogers Smith, Richard Valelly, Dorian Warren, the Department of Public and International Affairs at George Mason University, and the anonymous reviewers for Polity for their helpful comments and suggestions. This paper was written in part under the auspices of a 2002–2003 Brookings Research Fellowship.

Henry L. Dawes, “The Mode of Procedure in Cases of Contested Elections,” Journal of Social Science 2 (1870): 56–68 (64, 68).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Green, M. Race, Party, and Contested Elections to the U.S. House of Representatives. Polity 39, 155–178 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.polity.2300082

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.polity.2300082