Abstract

Recent decisions by the Spanish national competition authority (TDC) mandate payment systems to include only two costs when setting their domestic multilateral interchange fees (MIFs): a fixed processing cost and a variable cost for the risk of fraud. This artificial lowering of MIFs will not lower consumer prices, because of uncompetitive retailing, but it will however lead to higher cardholders’ fees and, most likely, new prices for point of sale terminals, delaying the development of the immature Spanish card market. Also, to the extent that increased cardholders’ fees do not offset the fall in MIFs revenue, the task of issuing new cards will be underpaid relatively to the task of acquiring new merchants, causing an imbalance between the two sides of the payment networks. Moreover, the pricing scheme arising from the decisions will lead to the unbundling and underprovision of those services whose costs are excluded. Indeed, the payment guarantee and the free funding period will tend to be removed from the package of services currently provided, to be provided either by third parties, by issuers for a separate fee, or not at all, especially to smaller and medium-sized merchants. Transaction services will also suffer the consequences of the fact that the TDC precludes pricing them in variable terms.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

TDC Decisions of 11 April 2005, No. A 314/02, Tasas Intercambio SISTEMA 4B; No. A 318/2002, Tasas Intercambio SERVIRED; No. A 287/00, Sistema Euro 6000.

Using as a reference the cost estimations of Visa and MasterCard in their cross-border card transactions within the European region, it can be concluded that the TDC excludes much of the total costs. The cost of the payment guarantee is estimated at 50 per cent of total costs by both Visa and MasterCard, and the TDC would only allow the inclusion of those related to fraud. The cost of the free funding period, which is fully excluded by the TDC, amounts to 26 per cent of total costs for Visa and 25 per cent for MasterCard. Finally, the processing cost, whose inclusion is allowed by the TDC as a flat fee, is estimated at 24 per cent of total costs by Visa and 25 per cent by MasterCard in their cross-border POS transactions within the European region. Percentages and more details are available at: http://www.visaeu.com/acceptingvisa/interchange.html and http://www.mastercardInternationalcom/corporate/mif_information.html (last accessed 15 September 2005).

In relation to interchange fees see, among others, David S. Evans and Richard Schmalen-see, Paying with Plastic, 2nd edn. (Cambridge, MA, MIT Press 2005); and the papers presented at two recent conferences: ‘Interchange Fees in Credit and Debit Card Industries: What Role for Public Authorities?’, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 4–6 May 2005, available at: http://www.kc.frb.org (last accessed 15 September 2005) and ‘Antitrust Activity in Card-Based Payment Systems: Causes and Consequences’, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, New York, 15–16 September 2005, available at: http://www.newyorkfed.org/research/conference/2005/antitrust_activity.html (last accessed 15 September 2005).

See Commission Decision 2002/914/EC of 24 July 2002 regarding Case No. COMP/29.373 — VISA International — Multilateral Interchange Fee, OJ 2002 L 318/17-36.

The decision conditions potential reductions in prices to strong competition in retailing: ‘In cases where there is strong price competition between merchants, the fall in merchants’ costs [due to possibly lower discount fees] could lead to reduced prices for all consumers, including those who pay by Visa card’ (para. 94).

International Monetary Fund, Report on Spain (Washington, January 2005); Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Economic Survey of Spain (Paris, 2005); and TDC, Informe sobre las condiciones de competencia en el sector de la distribución comercial (Madrid, 2003). The Spanish retailing market has become increasingly uncompetitive since 1985, due to the increased barriers to entry (redundant licensing) and the restrictive regulation of opening hours and sales existing in Spain, together with preferential taxation.

Grupo Parlamentario Catalán [Convergència i Unió], ‘relativa al cumplimiento de las resoluciones del Tribunal de Defensa de la Competencia en materia de fijación de tasas de intercambio aplicadas sobre los pagos efectuados mediante tarjetas de crédito o débito’, April 28, Boletín Oficial de las Cortes, 161/000900, Serie D, No. 199, 10 May 2005, p. 16.

Local monopoly power has been stressed as a main feature of Spanish distribution by the former President of the TDC. See Amadeo Petitbò, ‘Gallofas comerciales’, La Vanguardia, 15 August 2005.

See Benito Arruñada, ‘The Quasi-Judicial Role of Large Retailers: An Efficiency Hypothesis of their Relation with Suppliers’, 92 Revue d’Economie Industrielle (2000) pp. 277–296.

According to the data included in Commission Decision 2002/914/EC of 24 July 2002 regarding Case No. COMP/29.373 — VISA International — Multilateral Interchange Fee, OJ 2002 L 318/17-36.

Bank of Spain, ‘Capítulo del Bluebook sobre España’ (Madrid, 2001) p. 12, available at: http://www.bde.es/sispago/blueboo.pdf (last accessed 15 September 2005).

See https://www.pass.carrefour.es (last accessed 15 September 2005).

These are the percentages for Visa in Spain, according to Servired (TDC Decision of 11 April 2005, No. A 318/2002, Tasas Intercambio SERVIRED, p. 11).

The main changes in this regard, as well as their origins, are summarised at the end of section 2.4.

What might well be the first empirical evaluation of costs and benefits of alternative payment systems concludes that ‘when all key parties to a transaction are considered and benefits are added, cash and checks are more costly than many earlier studies suggest’. See Daniel D. Garcia Swartz, Robert W. Hahn and Anne Layne-Farrar, ‘The Economics of a Cashless Society: An Analysis of the Costs and Benefits of Payment Instruments’, AEI-Brookings Joint Center for Regulatory Studies, Related Publication 04–24, September 2004, available at: http://www.aei-brookings.org/publications/abstract.php?pid=842 (last accessed 15 September 2005).

Estimate based on the experience of a high-quality issuer.

Bank of Spain, ‘Evolución en España de las tarjetas como medio de pago (1996–2004)’, Estabilidad financiera, No. 8 (May 2005) p. 61, available at: http://www.bde.es/informes/be/estfin/numero8/estfin0802.pdf (last accessed 15 September 2005).

According to a recent report by the European Central Bank, Payment and Securities Settlement Systems in the European Union: Addendum Incorporating 2003 Figures (Frankfurt am Main, Germany, August 2005), available at: http://www.bde.es/sispago/bbestade.pdf (last accessed 15 September 2005), the number of transactions with credit cards per POS terminal is only 50.65 per cent of the EU average and, given that the average amount per transaction in Spain is also smaller, each terminal processes a total value which is only 37.34 per cent of the EU average. Utilisation rates are even lower for ATM withdrawals and, in particular, for the use of debit cards in POS terminals. Spaniards also use their cards less than the average European: utilisation is 65.95 per cent for cards with a cash function, 24.89 per cent for debit cards and 92.42 per cent for credit cards. Average values per transaction are also lower, with amounts which are only 79.51, 72.43 and 73.73 per cent of the EU average for these three types of card. Consequently, the corresponding estimated values of the total annual transactions per card for each type of card are only 52.43, 18.03 and 68.14 per cent of the EU average (see details in Table 2; data for cash holdings as of 2001).

Given that it is the cardholder who decides on the use of the card, incentives on the merchants’ side would require merchants devising ways of motivating cardholders. This has been a common practice for card stores (giving customers free parking space when using the store card or privileges in case of returns). In any case, it would be costly, probably ineffective and, more importantly, out of reach for small merchants.

He assumes that MIFs may be necessary in an immature payment card market when saying that in the United States, a very mature market, ‘bank card issuers sent nearly 5¼ billion direct mail solicitations to U.S. households in 2004 … [but] average response rate to these solicitation offers has fallen to only 0.4%. … So it would seem hard to claim that interchange fees are necessary today to overcome a chicken and egg entry barrier problem.’ Alan S. Frankel, ‘Interchange Fees in Various Countries: Comment on Weiner and Wright’, Conference on ‘Interchange Fees in Credit and Debit Card Industries: What Role for Public Authorities?’, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 4–6 May 2005, p. 9 [emphasis added].

This agreement was notified to the TDC and individually exempted by virtue of the Decision of 26 April 2000, No. A 264/99, Tasas Pago con Tarjeta.

Data from the European Central Bank, 2005, op. cit. n. 18. The central bank of Spain observes ‘in the last years a slight slowdown in the growth rate of the number of ATMs and POS terminals, being even possible to speak of stagnation for some quarterly observations.’ Bank of Spain, op. cit. n. 17, at p. 63.

Bank of Spain, op. cit. n. 17, at p. 62.

The unbalanced compensation between acquirers and issuers was partly responsible for the slow development of the market, as it was felt in Spain during the first years of the payment card market. Before the networks had been able to fine-tune their prices, the activity of acquiring merchants was rewarded better than that of issuing cards and, as a consequence, banks installed too many POS terminals and issued to few cards. Some time later, the price structure was changed in the opposite direction, resulting for a short while in the opposite imbalance in incentives and behaviours, before the current pricing structure was finally introduced, a structure that seems to have been motivating a balanced mix of both acquiring and issuing activities.

A recent article in the most influential Spanish business weekly asserted that a ‘change in the rules of the game [on MIFs] could alter the whole system of electronic payments in Spain and incline banks and savings and loans associations to migrate towards alternative payment systems’. ‘Los tribunales también “pasan” la tarjeta’, Actualidad Económica, 15 September 2005, p. 48.

The Commission concludes that ‘due to negotiation and transaction costs bilateral interchange fees though theoretically possible, would result in higher and less transparent fees. This is in its turn likely to lead to higher merchant fees.’ Commission Decision 2002/914/EC of 24 July 2002 regarding Case No. COMP/29.373 — VISA International — Multilateral Interchange Fee, OJ 2002 L 318/34, para. 101.

‘This conclusion [on the efficiency gains of a multilateral interchange fee due to lower negotiation and transaction costs in the context of the Visa international payment scheme] is not necessarily valid in a domestic context, where the number of banks may well be far fewer and the efficiency gains of a multilateral arrangement vis-à-vis bilateral agreements may not outweigh the disadvantage of the creation of a restriction of competition.’ Commission Decision 2002/914/EC of 24 July 2002 regarding Case No. COMP/29.373 — VISA International — Multilateral Interchange Fee, OJ 2002 L 318/34, n. 45.

Euro 6000 has 35 members, 4B has 31 members and Servired has 102 members. See Bank of Spain, op. cit. n. 17, at p. 59, n. 5.

World Bank, Doing Business in 2005: Removing Obstacles to Growth (Washington DC, Oxford University Press 2005).

Clara Fraile, ‘Cobro de morosos: Entre tres y cuatro de cada cien facturas emitidas se quedan sin pagar’, Consumer (May 2004), reporting on the basis of estimates produced by Intrum Justitia.

According to the official fee schedules of the two main banks, SCH and BBVA, published by the Bank of Spain: ‘Tarifas bancarias’, available at: http://www.bde.es/noticias/dot/tarbp.htm (last accessed 15 September 2005).

Millward Brown Spain, ‘Estudio sobre uso e imagen de la financiación en los servicios y consumo’, prepared for ASNEF, Madrid, February 2005, available at: http://www.asnef.com (last accessed 15 September 2005).

It is the so-called factoring without recourse, by which merchants sell their invoices for future payment. However, even in the more developed US market businesses, it is difficult to find a factor willing to operate with them if their monthly receivables add up to less than $10,000. And it is very expensive: factors pay 70 to 90 per cent of the face value of the debt upfront plus another fraction and this only after the debt is collected. The final total discount is usually between 5 to 10 per cent of face value, and varies with the payment period, the industry and the credit history of clients. Furthermore, it is unsuitable for firms with small transactions, which makes it useless for many merchants currently relying on credit cards. See, for instance, Business Owner Toolkit, ‘Factoring’, available at: http://www.toolkit.cch.com/text/P10_3730.asp; Vilma González Morales, ‘Aspectos generales relacionados con el factoraje’, available at: http://www.monografias.com/trabajos12/facto/facto.shtml; José Leyva, ‘El factoring, un negocio de autofinanciamiento’, available at: http://www.injef.com/php/index.php?option=content&task=view&id=361&Itemid=32 (all three last accessed on 15 September 2005).

In Spain, commercial credit insurance enjoys one of the highest penetration rates worldwide (around 0.060 per cent of GDP), accounting for 7 per cent of the world market. See Swiss RE, ‘El seguro de crédito comercial: La globalización y el negocio electrónico presentan grandes oportunidades’, Sigma 7, 30 September 2000, available at: http://www.swissre.com/INTERNET/pwsfilpr.nsf/vwFilebyIDKEYLu/SHOR-563HAK/$FILE/sigma7_2000_s_rev.pdf (last accessed 15 September 2005); and J.H., ‘El seguro de crédito, blindaje de las empresas frente a los impagos’, ABC, 21 November 2004. However, the number of insured firms is small, with estimates of around 34,000. Policies sold by Crédito y Caución (CyC), which enjoys a 60 per cent market share, are much worse than those bundled with credit cards, in terms of exclusions, complexity and coverage: CyC policies exclude sales to individuals, transactions below a minimum figure and sales exceeding the credit limit authorised by the insurer for each one of the insured’s clients. Its procedures are complex because before making an offer the insurer analyses the insured’s sector, turnover and credit terms, as well as the geographic distribution of its clients. Moreover, to eventually collect an indemnity, insured firms have to obtain a credit limit for each of their clients, report their total turnover on a monthly basis and pay the premiums, which are calculated as a variable proportion of sales. Creditors also have to exhaust friendly collection procedures, and after these fail, send the insurer a ‘claims notice’ and the original documentation for the unpaid credit. Only at that point a loss occurs and an indemnity is paid. But this indemnity is only a percentage of the insured loss and, therefore, provides incomplete coverage. See http://www.creditoycaucion.es/ingles/productos/seguro_credito.asp (last accessed 15 September 2005). All these exclusions and limitations probably remove much of the adverse selection and moral hazard potentially plaguing the industry. However, the average premium of credit insurance still reaches averages as high as 0.20 to 0.25 per cent of sales. See Patricia Pérez Zaragoza, ‘Las empresas se blindan con seguros de crédito’, El Comercio, 9 January 2005. It is therefore likely that a policy with the inclusiveness, full coverage and automatism of the insurance being now bundled with credit cards would cost many times that amount.

In this regard, see Margaret E. Guerin-Calvert and Janusz A. Ordover, ‘Merchant Benefits and Public Policy towards Interchange: An Economic Assessment’, Conference on Antitrust Activity in Card-Based Payment Systems: Causes and Consequences, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, New York, 15‒16 September 2005, available at: http://www.newyorkfed.org/research/conference/2005/antitrust/Guerin_Calvert_Ordover.pdf (last accessed 15 September 2005).

See George J. Benston and Clifford W. Smith, ‘A Transactions Cost Approach to the Theory of Financial Intermediation’, 31 Journal of Finance (1976) pp. 215–231.

Bank of Spain, Informe de Estabilidad Financiera, Madrid, May 2003, p. 23, available at: http://www.bde.es/informes/be/estfin/estfin.htm (last accessed 15 September 2005).

These estimates are based on insolvency rates for specialised credit outlets, as no separate data is publicly available for banks. See Bank of Spain, Informe de Estabilidad Financiera, Madrid, May 2005, p. 42, Graph I.5(c), available at: http://www.bde.es/informes/be/estfin/estfin.htm (last accessed 15 September 2005). A good part of its variability may have been caused by new entrants accepting higher rates of default in their first years of business. Estimates are also based downwards, however, because given the legal difficulties to proceed against credit cards users, many banks treat these non-payments as overdrafts on the associated current accounts, and the final defaults therefore end up misclassified. Even higher default rates are common in less developed markets. For instance, a recent report estimated defaults in 6.5 per cent of outstanding credit in Peru, according to Superintendencia de Banca, Seguros y AFP, Noticias Diarias, 5 May 2005, available at: http://www.sbs.gob.pe/PortalSBS/noticias/historico/2005/Mayo/05.05.2005.htm (last accessed 15 September 2005).

In application of the Bank of Spain’s Regulation 9/1999. See Bank of Spain, Informe de Estabilidad Financiera, Madrid, November 2002, pp. 26–27, available at: http://www.bde.es/informes/be/estfin/estfin.htm (last accessed 15 September 2005). Rule 4/2004, available at: http://www.bde.es/normativa/circu/c200404.pdf, enacted in January 2005 in order to adapt the Spanish standards to those of the International Accounting Standards Board, maintains the same consideration of credit card lending as one of the most risky forms of lending and makes the same allowances.

The problem is more general, affecting all industries which are dedicated to preventing risks and, as a consequence, have a hard time convincing clients and regulators about the reasonableness of their prices. What happens is that clients and regulators do easily perceive and recognise the costs of paying the losses that these firms suffer (defaults in the case of credit insurance). However, both clients and regulators are prone to miss, and are therefore reluctant to recognise, the less explicit but often greater costs incurred in preventing losses. On this, see Benito Arruñada, ‘A Transaction Cost View of Title Insurance and its Role in Different Legal Systems’, 27 The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance Issues and Practice (2002) pp. 582–601.

TDC Decision of 11 April 2005, No. A 314/02, Tasas Intercambio SISTEMA 4B, p. 35.

Same source as that in n. 31.

In the first quarter of 2005, 54.74 per cent of Spanish families found it difficult to make ends meet according to a survey of the National Statistical Institute, ‘Encuesta de Presupuestos Familiares’, Quarterly Survey (Madrid, 2005).

For instance, the data collected by Intrum Justitia showed that the average payment period of Spanish firms was 68 days, compared to an EU average of 39 days, only behind the 75 days of Greek firms. For the data, see Intrum Justitia, European Payment Habits Survey April 1997 (Amsterdam, Intrum Justitia 1997); and for an analysis, see Benito Arruñada, La Directiva sobre morosidad (Madrid, Marcial Pons — Instituto de Estudios del Libre Comercio 1999). The situation is getting worse: in a 2003 update of said data, the payment period was 67 days but the average delay increased to 13.4 days.

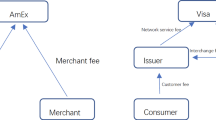

‘The Commission does accept that a four-party payment scheme is characterized by externalities, and that there is interdependent demand from merchants and cardholders’ (para. 65).

The evaluation of benefits should in any case be deduced from behaviour. Considering the high price of alternative services, it is hard to believe that merchants accept cards purely because of strategic reasons and not on the basis of the value they get from the services being provided.

Not without considering, however, that part of these costs might be paid by cardholders.

See Instituto Superior de Técnicas y Prácticas Bancarias, Práctica, normalización y regulación del sistema y los medios de pago (Madrid, 2005).

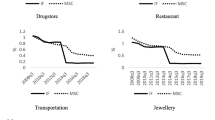

A reduction in the range of MIFs across sectors has already been observed in Spain since the 1999 agreement mentioned in n. 21. Maximum discount rates fell from 3.48 to 2.98 per cent, but minimum rates increased from 0.54 to 0.70 per cent between 2002 and 2004. See Bank of Spain, op. cit. n. 17, at p. 59.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Arruñada, B. Price Regulation of Plastic Money: A Critical Assessment of Spanish Rules. Eur Bus Org Law Rev 6, 625–650 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1017/S1566752905006257

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1566752905006257