Abstract

Purpose

A research prioritisation exercise was undertaken by the UK Paediatric Critical Care Society Study Group in 2018. Since then, the COVID-19 pandemic occurred and several multi-centre studies have been, or are being, conducted to address topics prioritised by healthcare professionals and parents. We aimed to determine how these priorities had changed in five years and post COVID-19 pandemic and compare these to international PICU priorities.

Methods

A modified three-round e-Delphi study was conducted in 2022 with surveys sent to all members of the Paediatric Critical Care Society. Following this, the top 20 topics were ranked and voted on using the Hanlon method in an online consensus webinar.

Results

247 research topics were submitted by 85 respondents in Round one. 135 of these were categorised into 12 domains and put forward into Round two, and were scored by 112 participants. 45 highest scoring topics were included in Round three and these were re-scored by 67 participants. Following this, the top 20 topics were voted on (using the Hanlon method) in an online consensus webinar in November 2022, to generate a top 10 list of priority research topics for pediatric critical care in 2023. The top research priorities related to complex decision-making in relation to withdrawing/withholding critical care, antimicrobial therapy and rapid diagnostics, intravenous fluid restriction, long-term outcomes, staffing and retention, implementation science and the role of artificial intelligence.

Conclusion

Some of the research priorities for pediatric critical care in the UK have changed over the last five years and there are similar priorities in other high-income countries with a potential for multi-national collaborations to address these key areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Conducting clinical research involving critically ill children and young people is vital because paediatric critical care (PCC) is a high-cost, resource-intensive environment with a sparse evidence base [1]. Much of clinical practice within PCC is not supported by high-quality evidence and practice surrounding even commonly used interventions can vary widely between units and individual intensivists [2]. With recognition that research is a vital component of a high quality service [3], there is an aspiration that research should be the standard of care for all critically ill children and their families [4].

A key element to overcoming these challenges has been the establishment of national and international research networks to promote a collaborative approach to the successful design and conduct of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) in PCC [5]. The Pediatric Critical Care Society (PCCS) is a professional, multi-disciplinary, membership organisation, representing the interests of those delivering pediatric critical care in the UK and Republic of Ireland [6]. The Society has developed UK quality standards which highlight the importance of research in service provision and established a research study group (PCCS-SG) [7]. PCCS-SG aims to improve the care of critically ill children and young people through the conduct of high-quality, multi-centre research studies within the UK and the Republic of Ireland (RoI) [5]. This coordinated approach is vital to develop methodologically robust trials to inform evidence-based guidelines within the PCC setting [8]. Currently there are a number of multi-centre RCTs in progress, aiming to recruit large number of patients. Oversight from PCCS-SG has meant these have been planned to run sequentially to avoid competition or there has been inter-trial collaboration to minimise burden associated with recruitment and consent. Research prioritisation is therefore an important function of the PCCS-SG [5], to ensure that the perspectives of healthcare professionals (HCP), children and young people and parent/carers are taken into account.

In 2018 the first formal PCCS-SG led research prioritisation exercise was conducted with the aim to identify and agree research priorities in PCC in the United Kingdom, both from a HCP and parent/caregiver perspective [9]. The exercise examined and compared HCPs and families’ views around research priorities in PCC and was disseminated to the PCC community through PCCS-SG meetings, presentation at the national PCCS research conference and publication. Following on from this, several studies have been or are being undertaken, have secured funding or are being developed as future trials.

The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on biomedical research around the world with a shift towards COVID and virology related research questions. There was also a reprioritisation of research staff and resources which affected research activity and delivery in other areas, with potentially disproportionately higher impact on pediatric research. Post-pandemic effects related to economic challenges may also have longer lasting impact on research funding and strategies are being developed to focus efforts on research recovery [10,11,12,13].

It is therefore timely to revisit and take stock of our current priorities post-pandemic and five years on. The aim of this study was to establish the research priorities of healthcare professionals working within UK PCCs in 2022 and to describe the extent to which they had changed since 2018.

Methods

A modified three-round e-Delphi study [14, 15] of PCCS members was undertaken, followed by the more rigorous Hanlon method of prioritisation [16], to generate an updated consensus around priority research areas for pediatric critical care in the UK. The three rounds of e-Delphi survey were completed between February and May 2022 and the Hanlon scoring was carried out in October 2022. This study is reported according to the Guidance on Conducting and Reporting Delphi Studies (CREDES) checklist for e-Delphi studies [17].

All PCCS members (n = 1200) were invited to complete the e-Delphi survey and two reminders were sent for each round at weekly intervals. The time between rounds was six weeks to reduce attrition. In round one (R1), respondents were asked to list up to three research topics or questions they deemed as key priorities for the specialty over the next five years using SurveyMonkey (SurveyMonkey, Mateo, CA). Respondents were encouraged to be specific in suggesting a study question and outcomes, considering the relevance to patient care. Participant demographics were also collected. There was an option to provide respondents’ email address to allow for any clarification of their question or topic. Simple content analysis was undertaken to classify responses from R1 into topic domains by three study team members (KM, LT, SR), following the analysis method [18]. This involved collapsing the suggestions into key domains and merging duplicate items; this was undertaken independently, and discrepancies resolved through an online discussion by the reviewers. Special consideration was given to retain original language used to frame questions by the respondents and duplicates were removed.

In round two (R2), topics and domains were sent to participants, who were asked to rate each topic on a scale between one (not an important topic) and six (the most important research topic). Optional free text comments were permissible. To generate topics for R3, we followed a two-step process: (a) selecting questions that scored more than the population mean, and (b) excluded questions with a score above the mean but that had a proportions of scores of 5 (‘very important’) or 6 (‘most important’) lower than any with score below the mean. This therefore accounted for both the average score for each question and the distribution of scores and addressed clustering around the central tendency (supplement 1). Free text comments were also reviewed by the study team to identify any topics that were already being studied and gain further insight into responses.

The R3 survey was sent back to participants with the group mean score and proportion ranked five or six, to re-rank in light of the group score. The same rating scale with one to six, was used. Participants were also asked to prioritise domains identified after the first round in the same way as the individual questions. This was carried out to consider developing research questions in particular areas for future prioritisation exercises.

Following this, the top 20 topics (by mean scores) were then converted into more structured research questions using a PICO format (Population, Intervention, Control, Outcomes) by members of the study team (SR, LT, PR). Members of PCCS-SG were invited to discuss and prioritise these topics during a consensus webinar according to the (i) size of the problem, (ii) seriousness of the issue, and (iii) feasibility of answering the research question. This session was moderated by an independent facilitator (LS) who was not a member of the PCCS and not involved in the design, conduction, or analysis of the e-Delphi study. Live online voting took place using Surveymonkey (SurveyMonkey, Mateo, CA) in this consensus webinar. The Hanlon prioritisation method [16] was then used to calculate Hanlon scores from the responses and the top ten research questions were identified.

Data analysis

Survey data were imported, validated, and analysed in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA), and STATA version 16 [19] was used for further analysis. During the consensus webinar each topic was scored on a scale from zero through ten on the pre-defined criteria. Priority scores were calculated using the following formula: D = [A + (2 × B)] x C, where: D = Priority Score, A = Size or prevalence of the issues, B = Seriousness of the issue, and C = feasibility of the study [16].

The survey was categorised according to the U.K. Health Research Authority as staff research and did not require formal NHS ethical approval. It was formally approved by PCCS-SG, who sent this out to the members of the society. Consent was implied by the return of the survey.

Results

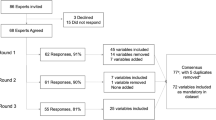

Eighty-five respondents submitted 247 research topics or statements during R1 (Fig. 1). Respondents were physicians (62%), nurses (27%) followed by other healthcare professionals, including dieticians (5%), advanced clinical practitioners (3%), and physiotherapists (2%). The mean (standard deviation (SD)) years of PCC experience were 14.3 (8.7) and 94% of the respondents were based in the UK. Once duplicates were removed, 135 topics were categorised into 12 domains (Table 1).

One hundred and twelve participants scored the 135 topics in R2. After this 45 of the 135 topics scored high enough priority to be entered into the R3 survey. Sixty-seven participants scored these in R3, and the top 20 topics were used for Hanlon prioritisation, based on the highest mean scores focusing on importance of the topic. Respondents were also asked to prioritise the key domains identified after R1, and five domains received a mean score higher than 4/5 with ‘improving outcomes after PICU’ receiving the highest score (mean = 4.75) followed by ‘pain and sedation’ (mean = 4.25), Monitoring, diagnostics, technology, and artificial intelligence (mean = 4.17), staffing and well-being (mean = 4.11), and ethical issues (4.03).

A list of top ten priority research questions was generated according to the Hanlon calculation (Supplement 2) which was attended by 21 members of PCCS-SG. These participants included established academics and clinicians with active involvement or interest in research in pediatric critical care.

Discussion

In this study, we not only described current research priorities for pediatric critical care according to HCPs in the UK in 2023, but also explored if there has been a shift in key research areas or topics over the last five years. The response rates were similar to the previous exercise conducted in 2018. This might reflect the small number of clinicians being academically active and the need for a more inclusive research culture in paediatrics as has been noted in previous studies [20]. The respondents were however representative of the wider MDT in PCC and included doctors, nurses and allied health professionals. In comparison to 2018, HCPs prioritised topics related to early rationalisation and a more targeted approach for antimicrobial therapy, especially related to respiratory infections (Supplement 3). There was also greater emphasis on involvement of families and patients to identify outcomes that are important to them and incorporating those into further clinical research. This was considered particularly important for longer term outcomes, including for children with traumatic brain injuries. A new priority topic that emerged was related to improving how research evidence is incorporated into daily clinical practice. Implementation science has become an increasingly important field of science as more RCTS are undertaken, yet the results not always implemented into practice [21] contributing to research waste.

Some topics were consistent in remaining a priority since 2018, such as interventions to improve staff morale and retention, optimal sedation strategies and intravenous fluid management. The highest priority for the next five years, consistent with the 2018 exercise, was research to inform the processes related to communication and decision-making regarding withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatment, which reflects a growing number of admissions to PCC for children with complex (often life-limiting) medical conditions [22]. One topic that increased in priority was Registered nurse (RN) staffing levels and optimal RN:patient ratios, with the need to study new approaches for delivery of nursing care in PCC, increasing from 10th priority by HCPs in 2018, to fifth in 2022. This is likely reflective of an increasing demand for PCC capacity and staffing levels across the country [23]. Workforce modelling is an area currently being explored within the adult ICU [24] but no studies are currently exploring this within the PCC context.

The names for research domains identified in this study were derived from the language used by respondents to phrase research topics. However, priority domains identified in 2022 based were similar to those in 2018, with the introduction of the use of artificial intelligence as a new research area in PCC (Table 2).

In comparison to other PICU research prioritisation exercises undertaken internationally, UK research priorities are similar to those identified by the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Paediatric Study Group (ANZICS PSG), with an emphasis on long term outcomes, fluid therapy, sedation strategies, antimicrobial decision making, staff retention and psychological support for families [25]. We also noted some similarities in research domains identified from a survey of clinician-researchers from low- and middle-income countries, including ventilation, nutrition and ethics in paediatric critical care as well as a need for building capacity [26] (Table 3). This highlights the potential for multi-national collaborative studies and a need for developing stronger collaborations between paediatric critical care societies to address these research topics.

Research in pediatric critical care has unique challenges such as a complex and relatively small patient population [1] and challenges related to parental involvement [27], on top of cultural and systematic barriers related to pediatric research in the UK [28]. This has resulted in historically limited numbers of RCTs in PICU [29]. Encouragingly, a number of research topics that were prioritised in 2018 have, or are being, addressed in current studies and trials. These include the OxyPICU trial [30] that compares liberal vs conservative peripheral oxygen saturation targets for children in PICU, the Enhance study, that aims to identify and investigate different models of providing end of life care for pediatric patients [31], and the SWell study that aims to investigate wellbeing interventions for PICU [32, 33]. Large multi-centre trials such as First ABC and SANDWICH have also studied ventilation and sedation strategies in PICU [34, 35]. Despite this, many of the key questions still need to be addressed, preferably in multicentre trials, which will be resource intensive.

In addition to existing resource limitations, research delivery in the UK was heavily affected by the COVID-19 pandemic [10,11,12], with research recovery and reset still requiring attention three years on [13]. It is crucial that new and innovative approaches are considered, including platform and adaptive trial designs to address these key areas and challenges related to co-enrolment within finite resources and existing infrastructure [5].

This study has some limitations that warrant mentioning; although parents and families of children of PCC patients were involved in the research prioritisation in 2018, we were unable to involve parents during this updated prioritisation study. This was not possible due to resource limitations and challenges with access to families during COVID-19 pandemic [36, 37]. The study was also limited by a low survey response rate (especially in R1). This was however, higher than the previous Delphi study in 2018. Although we collected data regarding length of experience in PCC, we did not collect demographic data for survey respondents such as sex, age and ethnicity. The percentage of nurses and allied health professionals who responded remained low compared to the ANZICS PSG study [19] (27% vs 59%) which may have impacted on the results. There are recognised challenges to research engagement of nursing and allied health professionals (AHPs) which are the focus of national strategies (CNO 2021, NHSE 2022). Within the PICU specialty we hope to specifically target this with targeted support, education and training for nurses and AHPs from the recently funded NIHR Paediatric Critical Care Incubator [38,39,40]. Finally, the Hanlon scoring only involved 21 HCP and this again may have impacted on the findings. Despite these, one strength of this study was the addition of this extra Hanlon scoring system with input from active academics and clinicians with interest in research in the field of pediatric critical care in the UK.

Conclusions

In the UK, research priorities for pediatric critical care have shifted over the last five years with more emphasis on complex decision-making in end-of-life care, rapid diagnostics and antimicrobial therapy, innovative strategies towards RN staffing ratios and studying the emerging potential for and impact of artificial intelligence in this field. Other research questions related to fluid therapy and sedative agents remain a priority and need to be addressed. The similarities between research areas of interest identified from prioritisation exercises conducted in different countries highlights the importance of multi-national collaboration for further research in pediatric critical care.

Availability of data and materials

Anonymised data could be made available on request.

Change history

30 July 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44253-024-00045-2

References

Kanthimathinathan HK, Scholefield BR (2014) Dilemmas in undertaking research in paediatric intensive care. Arch Dis Child 99(11):1043–9

Peters MJ, Argent A, Festa M, Leteurtre S, Piva J, Thompson A et al (2017) The intensive care medicine clinical research agenda in paediatrics. Intensive Care Med 43:1210–1224

Harding K, Lynch L, Porter J, Taylor NF (2016) Organisational benefits of a strong research culture in a health service: a systematic review. Aust Health Rev 41:45–53

Zimmerman JJ, Anand KJ, Meert KL, Willson DF, Newth CJ, Harrison R et al (2016) Research as a standard of care in the PICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med 17:e13-21

Peters MJ, Ramnarayan P, Scholefield BR, Tume LN, Tasker RC, United Kingdom Paediatric Critical Care Society Study Group (PCCS-SG) (2022) The United Kingdom Paediatric Critical Care Society Study Group: The 20-Year Journey Toward Pragmatic, Randomized Clinical Trials. Pediatr Crit Care Med 23(12):1067–1075

Paediatric Critical Care Society. 2022. The Paediatric Critical Care Society Study Group (PCCS-SG). 2022. Available at https://pccsociety.uk/research/pccs-study-group/. Accessed 24 Apr 2023.

Paediatric Critical Care Society. 2022. Welcome to the Paediatric Critical Care Society. https://pccsociety.uk/ Accessed 24 Apr 2023

Tume LN, Valla FV, Joosten K et al (2020) Nutritional support for children during critical illness: European Society of Pediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care (ESPNIC) metabolism, endocrine and nutrition section position statement and clinical recommendations. Intensive Care Med 46:411–425

Tume LN, Menzies JC (2021) Ray, S and Scholefield, 'Research priorities for UK pediatric critical care in 2019: healthcare professionals’ and parents’ perspectives’. Pediatr Crit Care Med 22(5):e294–e301

L Harper a, N. Kalfa b , G.M.A. Beckers, M. Kaefer d, et al On behalf of The ESPU Research Committee. The impact of COVID-19 on research. Journal of Pediatric Urology. 2020;16(5). 715–716

JonesH., Iles-Smith H, Wells M. Clinical research nurses and midwives - a key workforce in the coronavirus pandemic. Nursing Times. https://www.nursingtimes.net/opinion/clinical-research-nurses-and-midwives-a-key-workforce-in-the-coronavirus-pandemic-30-04-2020/ Accessed 30 June 2023

National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). NIHR’s response to COVID-19. https://www.nihr.ac.uk/about-us/our-key-priorities/covid-19/ 2023a. Accessed 23 Apr 2023

National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). Research recovery and reset. NIHR. https://www.nihr.ac.uk/researchers/managing-research-recovery.htm 2023b. Accessed 23 Apr 2023.

Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna H (2011) The Delphi Technique in Nursing and Healthcare Research. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester

Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna H (2006) Consulting the oracle: Ten lessons from using the Delphi technique in nursing research. J Adv Nurs 53:205–212

Hanlon JJ, Pickett GE (1984) Planning. In: Hanlon JJ, Pickett GE (eds) Public Health Administration and Practice, 8th edn. Times Mirror/Mosby College Publishing, St. Louis, MO, pp 188–200

Jünger S, Payne SA, Brine J, Radbruch L, Brearley SG (2017) Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat Med 31:684–706

Ritchie J, Spencer L (1994) Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess RG (eds) Analysing qualitative data, 1st edn. Routledge, London, pp 173–194

StataCorp (2019) Stata Statistical Software. Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC

Mustafa K, Murray CC, Nicklin E, Glaser A, Andrews J: Understanding barriers for research involvement among paediatric trainees: a mixed methods study. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18

Tume LN (2022) Do Research Prioritization Exercises Reduce Research Waste? Pediatr Crit Care Med 23(11):956–958

Rennick J, Buchanan F, Cohen E, Carnevale F et al (2022) Towards enhancing Paediatric Intensive Care for Children with Medical Complexity (ToPIC CMC): a mixed-methods study protocol using Experience-based Co-design. BMJ Open 12(9):e066459

Morris K Fortune PM. Paediatric Critical Care. GIRFT Programme National Specialty Report. https://pccsociety.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Paed-Critical-Care-GIRFT-report_final_April2022.pdf. Accessed 30 June 2023

Endacott R, Pattison N, Dall’Ora C, Griffiths P et al (2022) The organisation of nurse staffing in intensive care units: A qualitative study. J Nurs Manag 30(5):1283–1294

Raman S, Brown G, Long D (2021) Priorities for paediatric critical care research: a modified Delphi study by the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Paediatric Study Group. Crit Care Resusc 23:194–201

von Saint André-von Arnim Amelie O., Attebery Jonah, Kortz Teresa Bleakly et al: Challenges and Priorities for Paediatric Critical Care Clinician-Researchers in Low and Middle Income Countries. Front Pediatr. 2017; 00277

Menzies JC, Morris KP, Duncan HP et al (2016) Patient and public involvement in Paediatric Intensive Care research: considerations, challenges and facilitating factors. Res Involv Engagem 2:32

Mustafa K, Murray CC, Nicklin E et al (2018) Understanding barriers for research involvement among paediatric trainees: a mixed methods study. BMC Med Educ 18:165

Mark Duffett, Deborah J Cook, Geoff Strong et al: The effect of COVID-19 on critical care research: A prospective longitudinal multinational survey. : https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.21.20216945; this version posted 23, 2020 Accessed 23 Apr 2023

Peters MJ, Jones GAL, Wiley D, Wulff J, Ramnarayan P et al (2018) Conservative versus liberal oxygenation targets in critically ill children: the randomised multiple-centre pilot Oxy-PICU trial. Intensive Care Med 44(8):1240–1248

Papworth A, Hackett J, Beresford B et al (2022) End of life care for infants, children and young people (ENHANCE): Protocol for a mixed methods evaluation of current practice in the United Kingdom. NIHR Open Res 2:37

Butcher I, Morrison R, Balogun O, Duncan H et al: Burnout and coping strategies in pediatric and neonatal intensive care staff. Clin Pract Pediatr Psychol. 2023; Advance online publication.

Pountney J, Butcher I, Donnelly P, Morrison R, Shaw RL (2023) How the COVID-19 crisis affected the well-being of nurses working in paediatric critical care: A qualitative study. Br J Health Psychol 00:1–16

Ramnarayan P, Richards-Belle A, Drikite L et al (2022) Effect of High-Flow Nasal Cannula Therapy vs Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Therapy on Liberation From Respiratory Support in Acutely Ill Children Admitted to Pediatric Critical Care Units: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 328(2):162–172

Blackwood B, Tume LN, Morris KP et al (2021) Effect of a Sedation and Ventilator Liberation Protocol vs Usual Care on Duration of Invasive Mechanical Ventilation in Pediatric Intensive Care Units: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 326(5):401–410

Menzies J, Owen S, Read N, Fox S, Tooke C, Winmill H (2020) COVID-19: Challenges and opportunities for research nursing and nursing research on paediatric intensive care. Nurs Crit Care 25(5):321–323

ACP-UK Children, Young People and Families Network & BPA Division of Clinical Psychology, Open Letter Regarding Continued Restrictions on Family Visiting within Paediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care - ACP UK. Accessed 30 June 2023

Chief Nursing Officer. 2021. Making research matter Chief Nursing Officer for England’s strategic plan for research. V2. November 2021. NHS England and NHS Improvement 2021,London. https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/making-research-matter-chief-nursing-officer-for-englands-strategic-plan-for-research/ Accessed 25 Mar 2024

NHS England 2022. Allied Health Professions’ Research and Innovation Strategy for England Allied Health Professions’ Research and Innovation Strategy for England | Health Education England (hee.nhs.uk)/ Accessed 25 Mar 2024

NIHR funds new Incubators to support research careers. https://www.nihr.ac.uk/researchers/supporting-my-career-as-a-researcher/incubators.htm#:~:text=The%20NIHR%20Incubators%20address%20areas,a%20sustainable%20and%20meaningful%20way. Accessed 25 Mar 2024

Acknowledgements

Prof. Luregn Schlapbach, MD, PhD

FMH ICU, Pediatrics, Neonatology, FCICM

Head, Department of Intensive Care and Neonatology

University Children's Hospital Zurich – Eleonore Foundation

Steinwiesstrasse 75

CH-8032 Zurich

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All authors contributed towards study design, survey questionnaire, data collection and the final manuscript. KM, SR and TL performed quantitative and qualitative analysis. LT, RP and SR formulated the top priorities into PICO format questions for Hanlon scoring. JM provided background section of the manuscript. KM wrote the other three sections. These were then reviewed and modified with feedback from all co-authors. Contributions of authors are also listed in the methods section as appropriate.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicting interests for this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article has been updated to correct 1 author name.

Supplementary Information

44253_2024_42_MOESM1_ESM.tiff

Supplementary Material 1: Plot of mean scores and proportion of scores ≥ 5. To reduce the number of topics taken forward to R3, the topics that scored greater than the population mean (i.e. 3.71, blue line) AND have a proportion of scores of 5 or 6 higher than any of the questions that fall below the cut-off mean of 3.71 (i.e. 0.35, red line) were selected.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mustafa, K., Menzies, J., Ray, S. et al. UK pediatric critical care society research priorities revisited following the COVID-19 pandemic. Intensive Care Med. Paediatr. Neonatal 2, 20 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44253-024-00042-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44253-024-00042-5