Abstract

Background

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) overwhelmed health systems globally forcing doctors to make difficult triage decisions where healthcare resources became limited. While there have been several papers surveying the views of the public surrounding triage decisions in various disasters and many academic discussions around the moral distress suffered by physicians because of this, there is little research focussed on collating the experiences of the affected physicians in the critical care setting themselves.

Objective

The objective of this scoping review is to consolidate the available scientific literature on triage experiences and opinions of doctors (hereby used synonymously with physicians) working in the critical care setting during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly on issues of moral distress and the role of triage guidelines. In addition, this paper attempts to identify common themes and potential gaps related to this topic.

Methods

A comprehensive scoping review was undertaken informed by the process outlined by Arksey and O’Malley. Seven electronic databases were searched using keywords and database-specific MeSH terms: CINAHL, Emcare, Medline, PsychINFO, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science. Google Scholar and references of included articles were subsequently scanned. Included studies had to have an element of data collection surveying physician experiences or opinions on triage with a critical care focus during the COVID-19 pandemic from January 2020 to June 2023. A thematic analysis was subsequently performed to consider physicians’ perspectives on triage and collate any recurrent triage concerns raised during the pandemic.

Results

Of the 1385 articles screened, 18 were selected for inclusion. Physicians’ perspectives were collected via two methods: interviews (40%) and surveys (60%). Sixteen papers included responses from individual countries, and collectively included: United States of America (USA), Canada, Brazil, Spain, Japan, Australia, United Kingdom (UK), Italy, Switzerland and Germany, with the remaining two papers including responses from multiple countries. Six major themes emerged from our analysis: Intensive Care Unit (ICU) preparedness for triage, role and nature of triage guidelines, psychological burden of triage, responsibility for ICU triage decision-making, conflicts in determining ICU triage criteria and difficulties with end-of-life care.

Conclusions

While most studies reported critical care physicians feeling confident in their clinical role, almost all expressed anxiety about the impact of their decision-making in the context of an unknown pandemic. There was general support for more transparent guidelines, however physicians differed on their views regarding level of involvement of external ethics bodies on decision-making. More research is needed to adequately investigate whether there is any link between the moral distress felt and triage guidelines. In addition, the use of an age criterion in triaging criteria and the aetiology of moral distress requires clearer consensus from physicians through further research which may help inform the legislative reform process in effectively preparing for future pandemics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, health systems globally were put under immense strain as they tried to accommodate a significant surge in critically unwell patients [1, 2]. It took less than 3 months after COVID-19’s appearance in China before being declared a pandemic by the World Health Organisation (WHO) [3]. COVID-19’s most common severe clinical manifestation is severe respiratory distress, and ICUs subsequently became overwhelmed with a significant influx of patients as COVID-19 rapidly disseminated throughout largely unprepared communities [1, 4]. The dire consequences of this were described extensively in the literature in areas where COVID-19 affected health services with particular severity, such as Italy, the USA and Spain [1, 5]. With staffing shortages and limited resources, intensivists and critical care physicians describe being forced into making life-or-death decisions (such as ventilator allocation) for patients with minimal guidance [2, 5,6,7].

Triage in the disaster context has been described as necessary to more effectively make use of scarce resources, and should not be confused with the concept of triage applied routinely within the emergency department [8]. Instead, it applies following events that result in a quantity of injuries such that demand for services exceeds available resources [8]. This leads to a change in decision-making to focus on population-based outcomes and means some patients in well-resourced societies who would ordinarily have access to healthcare may have their access restricted [8]. However, there is no single accepted approach to disaster triage and it soon became clear that there was widespread variation in the availability, nature, specificity, and quality of guidelines, and their implementation between, and even within, jurisdictions during the COVID-19 pandemic [9, 10]. Many papers describe doctors suffering from moral distress because of these decisions they were required to make [6, 8, 11, 12]. This poses various questions as to the role of guidelines in supporting clinicians with making triage decisions in disaster contexts.

To explore this aspect of difficult critical care triage as part of the pandemic response, several papers have looked at collating and analysing the various ICU triage guidelines which were developed internationally [10, 13]. However, these papers do not adequately draw conclusions as to the impacts (psychological or otherwise) on physicians as they don’t directly explore the opinions of those making the clinical decisions based on these individual guidelines (i.e., intensivists).

While a notable scoping review looked at the public perspectives on tie-breaking criteria and the underlying values in COVID-19 ICU triage protocols, there appears to be no such reviews collating the viewpoints of physicians in this area [14]. A subsequent preliminary search of MEDLINE, PROSPERO, Open Science Framework, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and JBI Evidence Synthesis was conducted and no current or planned systematic reviews or scoping reviews on the topic of physician experiences of COVID-19 triage in the critical care setting were identified. The objective of this scoping review is therefore to assess and map the extent of the literature pertaining to the experiences and opinions of physicians working in the critical care environment with respect to triage during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, a scoping review approach would not restrict the scope of sources that could be considered, allowing for a broader assessment of the literature in this field, rather than a focus on the quality of data itself [15]. This will allow for identification of the common issues that are of most concern to physicians. In addition, by finding consensus or disagreement on various topics raised, this review will help provide legislators, managers, and administrators areas to best target reform to better support physicians working in the critical care setting in future pandemics.

2 Methods

2.1 Protocol and registration

The protocol and this paper followed the Arksey and O’Malley framework for scoping reviews, with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) informing the reporting guideline [16, 17]. The final protocol was registered with the Open Science Framework on the 8th of June, 2023 (https://osf.io/nmjfh/). The initial protocol methodology was followed with minor amendments after the first scoping search as outlined in 2.5.

2.2 Eligibility criteria

To be included in the review, papers needed to:

-

Have a thematic focus on experiences and/or opinions of physicians/doctors regarding triage in the critical care setting during the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

Have been published after January 2020 (deemed the “start” of the COVID-19 pandemic).

-

Be written in English.

-

Involve human participants.

Of note, some phrases and words were defined to meet the inclusion criteria:

-

Critical care was defined as “medical care for people who have life-threatening injuries and illnesses”.

-

The nature of COVID-19 blurred the clinical role of many medical specialists and a broadly inclusive definition of “physicians” rather than explicitly “intensivists” was used to ensure that elements of critical care performed outside ICU settings by other doctors were not missed in this review.

-

The definition of “triage” was kept intentionally broad to involve themes of pandemic resource-allocation and decision making.

-

To meet the definition of “experiences” or “opinions”, an element of prospective data collection from surveying doctors through various consultations was necessary, either through quantitative or qualitive elements, or a mix of both (through surveys, interviews, etc.).

Papers were excluded if they:

-

Did not include an element of data collection from doctors (i.e., abstract only, discussion paper, systematic review, position/society statement), or where triage or decision making was not a major focus of the article.

-

Included mixed doctor and non-doctor respondents (i.e., intensivists and nurses) where the results did not clearly separate the doctor respondents from the non-doctor respondents.

2.3 Information sources

The following seven databases were searched in early June 2023: CINAHL, Emcare, Medline, PsychINFO, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science.

2.4 Search

The search strategies were developed with assistance by an experienced librarian and further refined by the authors. The search strategy was tailored to include both database-specific MeSH terms, alongside additional keyword searches focussing on the five main subject headings of this review using Boolean operators; “COVID-19” AND “opinions” AND “intensive care” AND “triage” AND “survey”. Synonyms and keywords for each of these key subject headings were extracted from online thesauruses, trial database searches and the online Ovid Reminer tool [18]. Gray literature was not searched in this review, given the inability to perform quality appraisal on these sources. No search limitations were applied at this stage with respect to geographic location, date, or language. The search was performed over 2 weeks in June 2023. The electronic database search was supplemented by scanning the bibliographies of relevant articles to identify any relevant articles missed by the search strategy.

The entire search strategy for the CINAHL database is accessible in Supplementary File 1. The search strategies for the other six databases are available upon request.

2.5 Selection of sources of evidence

The final search results were exported into EndNote 20© [19], and duplicates were removed by both automated (using the inbuilt EndNote 20© duplicate finder) and manual means. Eligible reports were first screened in EndNote 20© using title/abstract against the inclusion/exclusion criteria by both the lead author (ES) and another reviewer (NK), who conducted the screening independently. Papers published prior to January 2020 were removed. After this initial screen, there was a discussion amongst all authors about the included papers, where a consensus was reached to refine inclusion/exclusion criteria, notably changing the focus of papers from a “significant focus” to a “focus” on triage, and explicitly excluding opinion/discussion papers. This was justified given a “significant focus” led to a significant restriction in scope for inclusion and some ambiguity as to what met this threshold after the initial search. The authors also agreed that excluding opinion papers allows for a more definitive methodological design of inclusion that allows for clearer comparison in the results. This was updated in the original Protocol.

A second stage of screening performed after this discussion was then performed by both reviewers (ES and NK) independently, involving review of the full text of all publications to assess potential inclusion. We resolved disagreements on study selection and data extraction by consensus discussion, and where disagreement persisted, a 3rd independent reviewer (TF) was engaged to act as a tiebreaker.

2.6 Data charting process

A data-charting Excel spreadsheet was jointly developed by two reviewers (ES and NK) to determine which variables to extract based closely on the JBI data extraction document for scoping reviews [20]. Reviewers independently extracted relevant portions of data to the data extraction template spreadsheet. Once this was done, both reviewers discussed the results, identifying any differences in data extracted before agreeing on a final data-charting form through a consensus approach, accessible as Supplementary File 2. This data extraction process is favoured by other authors, including Arksey and O’Malley on the conduct of scoping reviews [17].

2.7 Data items

The data-charting Excel spreadsheet included article characteristics, such as citation, country of respondent(s), study type, data collection period, study context and participant details. In addition, results of each study were tabulated into quantitative (i.e., Likert-scale responses, specific question responses in % format) and qualitative data (i.e., grouped themes and quotes where relevant). In papers with mixed respondents, data and quotes were only extracted and included where the physician results were clearly separated from non-doctor respondents.

2.8 Synthesis of results

Extracted quantitative and qualitative data were synthesised for thematic analysis. Through a framework analytic approach adapted to allow for synthesis of both data types in an unconventional, but not untested way [21, 22], ES undertook a preliminary reading of included studies and developed an initial thematic framework based on the main outcomes reported. Following a coding structure developed after this, ES extracted the most salient quotes and opinions from the selected studies. ES coded these opinions and the participants' views that were considered most relevant. As coding progressed, new themes were incorporated into the framework and previously coded studies were re-analysed within the updated framework. After discussing the final framework for thematic analysis, a consensus on the major themes was reached among all authors. Further sub-themes then emerged underneath the six major themes of this review. ES then grouped the studies by respondent demographics, geographic location of the survey and comparisons of time-periods for data collection. It is important to note that due to the inclusion of qualitative articles, this analytic process was simply aimed at synthesising the themes presented without drawing any conclusions as to consensus on certain views.

3 Results

3.1 Selection of sources of evidence

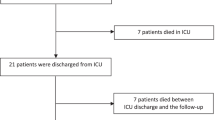

A flow chart (Fig. 1) was prepared according to the PRISMA Extension for scoping review (PRISMA-ScR) [16].

3.2 Characteristics of sources of evidence

The summary characteristics of each of the included studies are described in Table 1, which reports the author, year, country, objective(s), methodology, data collection time-period, respondent features and the key outcomes.

Of the studies included for analysis, 11 included responses solely from doctors, while the remaining 7 included a mix of doctor and non-doctor respondents.

16 publications involved respondents from individual countries, including from the USA (6), Canada (2), Brazil (1), Spain (1), Japan (1), Australia (1), UK (1), Italy (1), Switzerland (1) and Germany (1). The geographic origin of these 16 papers are visible in Fig. 2. The 2 remaining papers included responses from numerous countries, and therefore were excluded from this charting in Fig. 2, however the full list of countries included are available in Supplementary File 2 [23, 24].

3.3 Results of individual sources of evidence

The results were then classified according to the main themes as derived from the articles as part of the thematic content analysis (Table 2). Exemplar quotations from the interview papers are also included alongside relevant themes. The main themes are presented in percentages according to the number of papers which touch on the theme out of the total included articles (Fig. 3).

3.4 Synthesis of results

The primary aim of this scoping review was to identify the different experiences and opinions of physicians related to critical care triage during the COVID-19 pandemic and identify common themes. The research strategy resulted in 18 publications between 2020 and 2023. Of the 18 publications, 8 conducted their consultations through interviews, with the remaining 10 using questionnaire-based surveys.

3.4.1 ICU preparedness for triage

3.4.1.1 Insufficient staffing

Four papers directly explored staffing concerns [23, 30, 34, 36]. The first found that more doctors reported nursing limitations than intensivist limitations [23]. The other papers were more critical, with one paper quoting an intensivist who said, “we just didn’t have enough nursing… that was a big limiting factor… that I think might have affected patient care [34]…”. The remaining two papers echoed these concerns [30, 36].

3.4.1.2 Insufficient resources

Commentary on resource limitations was included in almost every paper [23, 24, 26,27,28,29,30,31,32, 34, 36]. Interestingly, one paper found only 4.7% of physicians felt that they were not able to provide necessary treatment due to a lack of medical resources [23]. In another paper, this view was shared, with intensivists expressing confidence in their own system’s surge capacity that there was a “resistance to consider possibility of secondary-population based triage operationalisation” [32]. Despite this, five papers were universally critical in their hospital’s resources with respect to availability of beds [24, 27, 28, 34, 36]. The topic of PPE limitations also arose in three papers related to access, re-use and training [23, 30, 34]. Two of these papers also described specific concerns about ventilator triage experiences [30, 34]. The first found that 66% had rationed resources with 21% of these physicians reporting rationing ventilators [30], while the second reported challenging experiences of using unfamiliar units such as transport ventilators [34].

3.4.1.3 Insufficient training

The final subtheme which arose from five papers was around training [25, 26, 29, 33, 38]. In general, physicians reported feeling confident in performing their clinical role during the pandemic [26, 29], although one paper found that residents were less confident than attending physicians [26]. A second paper supported this view and found that 85.4% reported that their training provided them with sufficient skills for their current responsibilities in the pandemic [33]. Three papers however described clear limitations in training, with one paper focussing on geriatric education insufficiencies [25], another describing deficits in PPE training [29] and a third finding 78% of respondents felt generally unprepared to make resource allocation decisions [38].

3.4.2 Role and nature of triage guidelines

3.4.2.1 Changing, inconsistent, unclear, untrustworthy guidelines

Nine papers described different concerns regarding triage guidelines [24, 27, 28, 30, 34,35,36,37,38]. Three papers explored constantly changing ICU admission criteria and policies [27, 35, 36], with a further two papers [28, 34] describing changing policies in other areas; the first describing this in the context of therapeutic strategies and shift schedules [28] and the second with PPE recommendations [34]. Three papers found that most respondents had access to some form of triage guidelines [24, 30, 38]. The main issues in the remaining articles arose from the clarity of the guidelines themselves. One paper described concerns about a lack of transparency [34] and in another paper, criticism was expressed about acting in the context of limited knowledge of the disease [36], with a final paper establishing that transparency about the triage process as a whole was seen as “critical for fostering trust and cooperation from clinicians, triage team members and the public” [37].

3.4.2.2 Support for guidelines

Support for guidelines was the second sub-theme which arose out of seven papers [24, 26, 29, 32, 34, 38, 39]. In general, most papers supported the development and implementation of triage guidelines, with the main variability in views related to how they should apply in pandemics. Five papers describe overwhelming support for triage guidelines to support resource allocation decisions [24, 26, 34, 38, 39], with another study expressing that doctors expected hospitals and governments would support their decisions and protect them from criticism or consequences [32]. Interestingly, one paper found that less than half of physicians conveyed concern regarding lack of uniform clinical guidance and treatment strategy in their hospital [29], demonstrating the differing views in this area. There were however some caveats to the papers that in general expressed support for guidelines. In one paper, doctors felt that they should remain responsible for allocating resources they routinely manage [32], and this was echoed in another paper where only 20% wanted to remove decision-making responsibility from individual physicians, with 9% preferring a more flexible policy that would allow physicians the leeway to make choices in line with their individual values [38]. In the paper by Merlo et al., intensivists were divided, with 3 participants viewing the guidelines as a source of direction, while 4 stated that instead they should serve as a “general framework” that is subject to interpretation [39].

3.4.3 Psychological burden of triage

3.4.3.1 Anxiety and fear of the unknown

Six papers reported feelings of anxiety related to decision making [26, 28, 32, 35, 36, 38]. One paper described 65% of respondents feeling “anxious” due to the pandemic and over half concerned about the psychological impact of resource allocation [26], while another two studies went on to describe a fear about the future given the knowledge gap [28, 35]. Another paper conveyed concerns about resource-driven decisions conflicting with patient prognoses [32], quoting one physician who said “I think the challenge is… you’ve got otherwise well middle-aged people… who ordinarily would expect to be sick, go [to ICU], survive, [and] go home who may be dying because they can’t access the resources they need…” A further two articles reporting other specific neuroses faced by physicians because of these triage decisions [36, 38]. Two studies included some responses from physicians worried about the legal culpability of their decision making [26, 38].

3.4.3.2 Moral distress

Nine papers examined feelings of moral distress related to decision-making [23, 27, 28, 31,32,33, 35,36,37]. Two papers focussed on concerns related to patient triage, with one describing “extreme tension” when physicians were requested to hospitalise young patients [27], and another describing the ethical conflicts of limiting life-sustaining treatment in order to free up beds for other admissions [28]. A further four papers focussed on the consequences of their decisions [23, 32, 35, 37], with one finding that over half of doctors reported worries about transmitting diseases to their families and just under half of doctors reported burnout as a result of their decisions [23]. The paper by Horn also explored this, with one doctor quoted saying “… it would have had an impact on subsequent reflection and rumination, and the soul-searching that would no doubt follow” [32], a concern shared in two other papers [35, 37]. An additional three papers explored other causes of distress [31, 33, 37], with one paper reporting “insufficient skills and expertise” and “inconsistencies between first COVID-19 triage decisions and physicians’ core values” as the most significant predictors for severe distress suffered by physicians [33]. Despite this, this same paper found that clinical guidelines nor targeted COVID-19 clinical training for COVID-19 had any impact on self-reported distress scales [33] which conflicts with the findings in another paper which found that moral distress was indeed associated with changeable selection criteria [36]. A final paper found that 46% of physicians reported that they experienced moral distress in ICU care during the COVID-19 pandemic, which was slightly less than the experience in normal times (48.4%) [31].

3.4.4 Responsibility for ICU triage decision-making

3.4.4.1 Role of the ethics committee

The first sub-theme surrounds the role of the ethics committee in triage decision-making, with four papers finding that clinician decision making should still be preserved in triage settings, although to varying degrees [24, 32, 37, 40]. The survey by Horn found that intensivists should remain responsible for allocating resources that they routinely manage, and that deferring to a panel (such as an ethics committee) felt like an “impractical interruption to clinical care” [32]. Another paper found that some respondents appreciated input from ethicist team members to help clarify thinking and expose value conflicts where they arose [37]. In the paper by Gessler et al., when faced with an ICU bed shortage, a majority favoured the “involvement” of local ethics committees where patient triage/diversion of resources is necessary [40]. A final paper found that the proportion of physicians who reported a positive inclination to consult colleagues in the ICU or clinical ethical committee about triage dilemmas was similar (87–88% or 51–53%, respectively), regardless of the particular dilemma [24]. These results show the role of the ethics committee is divisive among physicians.

3.4.4.2 Shared decision-making among intensivists

The second sub-theme relates to shared decision-making in triage and was explored in eight papers [23, 32, 34, 35, 37,38,39,40]. Most of the papers communicated that collaboration among fellow doctors was essential to effective triage, and that group consensus may be seen as a way of diffusing the moral burden of responsibility for a consequential task [35, 37, 39]. The UK paper by Sawyer et al. describes physicians relying on experiential knowledge among peer intensivists (on WhatsApp group chats for example), particularly in the early phase of COVID-19, when research was sparse [35]. Five papers all expressed opinions that physicians should remain responsible for decision-making, or at least key stakeholders [23, 32, 34, 38, 40].

3.4.5 Conflicts in determining ICU triage criteria

3.4.5.1 Age-criterion in triage

Of the seven papers which mentioned age being involved in triage [24, 25, 27, 37,38,39,40], all but three papers [27, 37, 39] expressed general support for its inclusion as part of the decision-making process. One paper found that most respondents reported age as an important factor [38], a finding also echoed in the article by Gessler et al. where 69% of respondents put “patient age” as the most important determinant of triage where all ICU resources are exhausted, and 61% also feeling that the principle of “youngest first” was important with regard to triage [40]. Another paper found that regardless of ethical dilemma, most respondents preferred to ventilate the younger patient [24]. This contrasts to the paper by Merlo et al. where all participants instead reported that age was never considered and that they always relied on a futility score rather than a distributive justice principle [39]. The remaining two studies conversely described various concerns and “difficulties” with triaging based on age [27, 37].

3.4.5.2 Competing triage determinants and institutional interests

A second subtheme which arose in three papers was to do with competing triage determinants and institutional interests [27, 38, 40]. One paper described physicians weighing up distance of residence to the ICU, transport difficulties, age, as well as family pressures for determining ICU admission [27]. Another study found physicians overwhelmingly agreed on certain factors that would be important in resource allocation including survival likelihood and presence of comorbidities [38]. The paper by Gessler et al. elicited some more variety, with 98% reporting “known patient wishes” as one of the “most important determinants” affecting triage, followed by 96% for “known state of health before acute deterioration”, 85% for “SOFA score” and 69% for “patient age” [40].

3.4.6 Difficulties with end-of-life care

3.4.6.1 Dying alone

A feeling of isolation in the end-of-life setting was expressed in two papers [28, 36]. In the first paper, physicians spoke about the ethical conflict of limiting life-support treatment and reported that the “possibility of them dying alone” were major sources of ethical conflict for physicians [28]. The second paper also went on to describe the separation of family members at the end-of-life, which amplified moral distress [36].

3.4.6.2 Changes in palliative care delivery

Change in palliative care delivery was noted in five papers [34, 36,37,38,39]. In one paper, participants described being encouraged to focus on comfort measures over aggressive treatments in patients with poor prognoses [34], a theme similarly present in another study where one respondent is quoted saying “we didn’t have any more beds in the ICU, we found ourselves distributing opioid [sic] to do palliative care to people who normally we would have saved [36].” The paper by Dewar et al. shared this view, with a majority of respondents reporting that they would find it difficult to provide palliative care to a patient who had been denied life-saving treatment because of resource-allocation decisions [38]. Two other papers detail other concerns, the first about inadequacies in accessing palliative care services [37], and the second describing a return to paternalism and failure to consult Advance Health Directives (AHDs) during triage decisions [39].

4 Discussion

4.1 Summary of evidence

In this scoping review we identified 18 primary studies addressing various experiences of COVID-19 triage in the critical care setting published between January 2020 and June 2023. The emerging themes and sub-themes were the product of our analysis.

The most expressed experience reported in the studies included this review relates to exposure to resource limitations in the ICU setting, particularly with respect to staffing, beds, and PPE. This is consistent with the wider literature, particularly at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, where PPE was in global shortage, and re-use became commonplace in many jurisdictions creating moral problems for physicians forced to treat patients without adequate protection [41, 42]. Despite this, most physicians surveyed felt confident in being able to triage in a pandemic context and it is a significant finding of this review that while intensivists may well be suffering from the moral consequences of various resource limitations, many simultaneously didn’t feel that they were necessarily unprepared. Despite this, other doctors like emergency physicians as Mulla et al. discovered, are less confident in their ability to triage [26], with some emerging evidence in the literature to suggest that perhaps non-intensivists should receive triage training, because, by virtue of the nature of a disaster, they are thrust into triaging critically unwell patients outside their usual clinical scope [43, 44]. Only a few papers touched on the concerns surrounding ventilator triage [24, 30, 34], however of those that did; concerns around delivery, training and withdrawal arose, which is consistent with the broader concerns raised in the literature [2, 11, 45, 46].

While there is general agreement that guidelines should be more transparent, it is also interesting to note the variability in physician opinion on certain themes, such as the role of guidelines and responsibility for decision-making. Overall, most papers agreed that shared decision-making helped dilute the moral burden of responsibility, though there was disagreement as to who should share this role. While some physicians felt comfortable deferring these decisions to external ethics bodies or rigid guidelines, some physicians rejected this and instead strongly favoured the complete independence of ICU doctors when making triage decisions, perhaps highlighting some hypocrisy to their feelings. Notwithstanding this point, most papers were critical to some degree of the existing triage frameworks that were put in place, and this is consistent with the wider literature, revealing significant inconsistencies and criticism of the guidelines developed across jurisdictions [47,48,49,50,51,52]. A notable systematic review conducted by Tyrrel et al. in [9] collated all the various triage frameworks implemented at the start of the pandemic and concluded that in general “the quality of the guidance was poor” and went on to criticise that many of the guiding ethical principles were not made explicit, adding that “while it may be simpler to leave prioritisation to the clinicians, there is a risk that if the principles and criteria used are not transparent, public trust may be undermined [9].” It should be noted that, perhaps as a consequence this, as Sawyer et al. makes clear, a reliance on shared decision-making became commonplace [35], and as Butler et al. establishes, this may well represent an attempt to shift the “moral burden” of responsibility [37], a conclusion reached in numerous other studies [53, 54].

It is also clear that the negative psychological impact of critical care triage in disasters should not be understated. Almost all papers described some element of distress associated with triage, and this reflects the significant body of literature describing the harrowing experiences of physicians making decisions during disasters [1, 48, 54]. Only two papers specifically looked at the aetiology of moral distress to do with pandemic triage [33, 36], and this makes it difficult to make judgements as to the direct impact of guidelines of intensivists, even though there is an abundance of research which suggests that introducing frameworks to guide decision-making helps relieve the moral burden of decision-making [55, 56]. What is apparent from the papers however is that making decisions against one’s core values and insufficient skills and expertise leads to more severe distress, and this suggests that better training as some authors argue [57, 58], and development of guidelines that reflect community values, may help with this as well. Given that one paper found that dedicated COVID-19 clinical training nor clinical guidelines had any real impact on self-reported distress felt when making triage decisions goes to show more research is needed to explore exactly how to relieve this distress [33]. Identifying these aetiological factors will have enormous implications for minimising any future moral distress felt by physicians in future pandemics. Two papers also touched on the legal consequences of decision-making [26, 38], a concern raised by numerous other academics [56, 59], and therefore reaffirms a need for government to clarify legal protection in critical care decision-making. Without this, doctors may hesitate (potentially with lethal outcomes) to make necessary triage decisions due to uncertainty about future litigation.

One of the other major findings of this review is the variety of opinions on triaging priorities, with some arguing for and against age being included as a criterion. Interestingly, the broader literature is about as conflicting as the opinions expressed in this paper, with various jurisdictions either explicitly excluding the criterion or intentionally keeping the guideline vague [12, 60, 61]. Some ethicists even argue outright for explicit prioritisation of younger patients [2, 62]. Understanding these triage priorities is also important when another major finding of this paper is to do with perceived inadequacies of end-of-life care delivery in the pandemic. These concerns have also been expressed in the wider literature, from the perspectives of numerous healthcare workers [63, 64], and while one may think end-of-life care is outside the scope of “critical care”, as Mercadante et al. argues, the two fields are closely intertwined [65], especially in times of disasters. Indeed, others paper have explored the moral issues of poor compliance with utilising AHDs during the pandemic [51, 66, 67]. This paper has collated the available literature related to experiences of critical care triage during COVID-19. The numerous concerns raised have implications for legislators to explore how to better address resource limitations, the psychological impact of triage and implement guidelines that best suit the needs of critical care physicians. It also has implications for the public, in ensuring that the determinants of triage are transparent, and as a natural corollary of this; that the best medical decisions are being made in times of great health crises.

4.2 Recommendations

-

Despite ventilator allocation being perhaps the most discussed moral issue in pandemic triage, there was an apparent lack of studies focussing on this issue specifically, and therefore ought to be explored in further research.

-

Given there is significant contention in how physicians weigh the involvement of external ethics bodies and clinical guidelines on clinical decision-making, more research is needed to further explore these viewpoints and adequately stratify the consensus in this area.

-

The legal consequences of ICU triage decision making in disaster scenarios needs to be clarified by governments as this may minimise the moral distress faced by physicians in times of uncertainty.

-

Given the relative acuteness of COVID-19, the long-term psychological implications of these decisions are unclear and warrant further investigation.

-

Given the apparent variation among intensivists with respect to certain triaging priorities, more targeted research is needed to explore the broad ethical values of intensivists, not only to assess whether they are generally consistent among physicians but also to see whether they are being made within a framework that is consistent with generally held community values.

4.3 Limitations

The research strategy was limited to English only articles, which may have potentially missed relevant papers outside the English-speaking world. Grey literature was also excluded, potentially missing informal surveys of physicians (i.e., online FaceBook polls) outside the setting of ethics-approved research. It should also be noted that non-interview or survey based qualitative studies such as ethnographies were not included in this study. Studies including ethnographies exploring experiences of healthcare workers during COVID-19 my provide deeper insight into the lived experiences of healthcare workers making triage decisions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite this, the choice of a scoping review gave us the recourse to include a wide variety of studies with different means of surveying physicians and an international scope to greatly increase the likelihood that the variety of opinions expressed in the wider literature were not missed.

Given the ongoing nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, we also cannot rule out the possibility that several studies had not yet been published. There is also a risk of selection bias when one considers the possibility that the most adversely affected doctors may have left the profession and therefore would be deemed ineligible to participate in the surveys included in this review. As part of the data extraction, additional detail pertinent to the participants such as clinical experience, or type of doctor was not included, as certain papers did not include this detail and would have complicated data synthesis. Instead, all doctors (i.e., intensivists, emergency doctors) were described as “physicians”. This means it is not possible to establish the nuanced perspective of individual specialties. In addition, this scoping review included papers where opinions expressed were not reported based on respondent numbers in percentages, therefore the results of this scoping review should not be taken as reflecting the consensus views of the populations surveyed, but instead merely synthesising the broad opinions expressed by respondents reported in the literature.

It should also be noted that three papers were included where the data collected was derived from perceived experiences, or from simulated environments [24, 32, 37]. This data, while valuable in the discussion, may potentially be perceived as being of lesser value than the data directly from physicians who suffered lived experiences of the triage issues discussed in this paper.

This paper does have many strengths though—it is the first of its kind to rigorously identify and synthesise the broad voices, opinions and experiences on triage from the perspectives of intensivists during COVID-19 and isolates several key areas of contention among physicians on crucial issues pertinent to triage, such as the role of guidelines, involvement of external ethics bodies and moral priorities of triage. By being somewhat selective in its inclusion criteria, it also allows for a critical-care voice that distinguishes it from other papers which have focussed on the experiences healthcare workers more broadly. This will help tailor the research priorities moving forward in helping us better prepare for pandemics while altogether finding new ways to support our physicians who will face triage into the future.

4.4 Conclusions

This scoping review provides an overview of the opinions and experiences of doctors engaged in critical care triage during the COVID-19 pandemic as reported in the literature. We obtained six emerging themes from our thematic analysis, with several key findings. Physicians almost universally expressed concerns about lack of beds, insufficient PPE and the consequences of their decision-making, despite feeling generally prepared in their clinical role. Some physicians expressed unease about ventilator allocation and end-of-life care delivery. There was general support for the development of clearer triage guidelines, despite differing views across the surveyed physicians as to the level of involvement of external parties like ethics committees and use of an age-criterion. The aetiology of moral distress also remains uncertain, and more research, perhaps through in-depth interviewing of critical care doctors or more focussed systematic reviews and meta analyses of ethical conflicts arising in triage beyond the scope of COVID-19 is needed to adequately find consensus on these issues and explore any link that may exist between lack of adequate triage guidelines and moral distress.

We hope these findings will help contribute to the ongoing public health discussion about how governments can help minimise the distress of physicians involved in critical care triage in future pandemics.

Data availability

All the data and materials of this study (Tables, Figures, Geographic Map, and Additional Files) are incorporated within this publication.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus Disease 2019

- USA:

-

United States of America

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- WHO:

-

World Health Organisation

- ICU:

-

Intensive Care Unit

- JiTT:

-

Just in Time Training

- PPE:

-

Personal Protective Equipment

- CAQS:

-

Critical Appraisal of a Qualitive Study

- CAS:

-

Critical Appraisal of a Survey

- S-PBT:

-

Secondary Population Based Triage

- SAMS:

-

Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences

- AHD:

-

Advance Health Directive

References

Fagiuoli S, Lorini FL, Remuzzi G. Adaptations and lessons in the province of Bergamo. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):e71. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2011599.

Persad G, Joffe S. Allocating scarce life-saving resources: the proper role of age. J Med Ethics. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2020-106792.

Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(1):157–60. https://doi.org/10.2375/abm.v91i1.9397.

De Del Pilar Antueno M, Peirano G, Pincemin I, Petralanda MII, Bruera E. Bioethical perspective for decision making in situations of scarcity of resources during the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Moral. 2022;71(1):25–8. https://doi.org/10.4081/mem.2022.1197.

Rosenbaum L. Facing covid-19 in Italy—ethics, logistics, and therapeutics on the epidemic’s front line. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2005492.

Ozan E, Durgu N. Being a health care professional in the ICU serving patients with covid-19: a qualitative study. Heart Lung. 2023;57:6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2022.07.011.

Griffiths F, Svantesson M, Bassford C, Dale J, Blake C, McCreedy A, et al. Decision-making around admission to intensive care in the UK pre-COVID-19: a multicentre ethnographic study. Anaesthesia. 2021;76(4):489–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15272.

Lewis CP, Aghababian RV. Disaster planning, part I. Overview of hospital and emergency department planning for internal and external disasters. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1996;14(2):439–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0733-8627(05)70261-3.

Tyrrell CSB, Mytton OT, Gentry SV, Thomas-Meyer M, Allen JLY, Narula AA, et al. Managing intensive care admissions when there are not enough beds during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Thorax. 2021;76(3):302–12. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215518.

Aquino YSJ, Rogers WA, Scully JL, Magrabi F, Carter SM. Ethical guidance for hard decisions: a critical review of early international COVID-19 ICU triage guidelines. Health Care Anal. 2022;30(2):163–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10728-021-00442-0.

Norisue Y, Deshpande GA, Kamada M, Nabeshima T, Tokuda Y, Goto T, et al. Allocation of mechanical ventilators during a pandemic: a mixed-methods study of perceptions among Japanese health care workers and the general public. Chest. 2021;159(6):2494–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2021.01.015.

Romanò M. Between intensive care and palliative care at the time of CoViD-19. Recenti Prog Med. 2020;111(4):223–30. https://doi.org/10.1701/3347.33185.

Piscitello GM, Kapania EM, Miller WD, Rojas JC, Siegler M, Parker WF. Variation in ventilator allocation guidelines by us state during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e2012606. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.12606.

Ramirez CC, Farmer Y, Bouthillier M-E. Public voices on tie-breaking criteria and underlying values in COVID-19 triage protocols to access critical care: a scoping review. Discov Health Syst. 2023;2(1):16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-023-00027-9.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x.

Tricco A, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien K. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMAScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

Ovid Citation Analyser: Wolters Kluwer. 2023. https://tools.ovid.com/reminer/. Accessed 25 June 2023.

The EndNote Team. EndNote. EndNote 20 ed. Philadelphia, PA: Clarivate; 2013.

Francis. E. 11.2.7 Data extraction: JBI Global. 2022. https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/4687700. Accessed 21 June 2023.

Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-117.

Roberts K, Dowell A, Nie J-B. Attempting rigour and replicability in thematic analysis of qualitative research data; a case study of codebook development. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0707-y.

Wahlster S, Sharma M, Lewis AK, Patel PV, Hartog CS, Jannotta G, et al. The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic’s effect on critical care resources and health-care providers: a global survey. Chest. 2021;159(2):619–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2020.09.070.

Fjølner J, Haaland ØA, Jung C, de Lange DW, Szczeklik W, Leaver S, et al. Who gets the ventilator? A multicentre survey of intensivists’ opinions of triage during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2022;66(7):859–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/aas.14094.

Altin Z, Buran F. Attitudes of health professionals toward elderly patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2022;34(10):2567–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-022-02209-6.

Mulla A, Bigham BL, Frolic A, Christian MD. Canadian emergency medicine and critical care physician perspectives on pandemic triage in COVID-19. J Emerg Manage. 2020;18(7):31–5. https://doi.org/10.5055/jem.2020.0484.

dos Santos Pereira JF, de Souza BF, de Carvalho RH, Oliveira Pinho JR, Fonseca Thomaz EBA, Carvalho Lamy Z, Duailibe Soares R, et al. Challenges at the front: experiences of professionals in admitting patients to the intensive care unit during the COVID-19 pandemic. Texto Contexto Enfermagem. 2022;31:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-265X-TCE-2022-0196en.

Falco-Pegueroles A, Bosch-Alcaraz A, Terzoni S, Fanari F, Viola E, Via-Clavero G, et al. COVID-19 pandemic experiences, ethical conflict and decision-making process in critical care professionals (Quali-Ethics-COVID-19 research part 1): an international qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16633.

Kaplan LJ, Kleinpell R, Maves RC, Doersam JK, Raman R, Ferraro DM. Critical care clinician reports on coronavirus disease 2019: results from a national survey of 4,875 ICU providers. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2(5):e0125. https://doi.org/10.1097/cce.0000000000000125.

Zalesky CC, Dreyfus N, Davis J, Kreitzer N. Emergency physician work environments during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Emerg Med. 2021;77(2):274–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.09.007.

Seino Y, Aizawa Y, Kogetsu A, Kato K. Ethical and social issues for health care providers in the intensive care unit during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: a questionnaire survey. Asian bioeth. 2022;14(2):115–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41649-021-00194-y.

Horn ZB. Factors impacting readiness to perform secondary population-based triage during the second wave of COVID-19 in Victoria, Australia: pilot study. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2023;17:e371. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2023.41.

Chou FL, Abramson D, Dimaggio C, Hoven CW, Susser E, Andrews HF, et al. Factors related to self-reported distress experienced by physicians during their first COVID-19 triage decisions. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2021.170.

Vranas KC, Golden SE, Mathews KS, Schutz A, Valley TS, Duggal A, et al. The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on ICU organization, care processes, and frontline clinician experiences: a qualitative study. Chest. 2021;160(5):1714–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2021.05.041.

Sawyer I, Harden J, Baruah R. Intensive care clincians’ information acquisition during the first wave of the Covid 19 pandemic. J Intensiv Care Soc. 2023;24(1):40–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/17511437221105777.

Lamiani G, Biscardi D, Meyer EC, Giannini A, Vegni E. Moral distress trajectories of physicians 1 year after the COVID-19 outbreak: a grounded theory study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(24):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413367.

Butler CR, Webster LB, Diekema DS, Gray MM, Sakata VL, Tonelli MR, et al. Perspectives of triage team members participating in statewide triage simulations for scarce resource allocation during the COVID-19 pandemic in Washington State. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(4):e227639. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.7639.

Dewar B, Anderson JE, Kwok ESH, Ramsay T, Dowlatshahi D, Fahed R, et al. Physician preparedness for resource allocation decisions under pandemic conditions: a cross-sectional survey of Canadian physicians, April 2020. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(10):e0238842. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238842.

Merlo F, Lepori M, Malacrida R, Albanese E, Fadda M. Physicians’ acceptance of triage guidelines in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Front Public Health. 2021;9:695231. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.695231.

Gessler F, Lehmann F, Bosel J, Fuhrer H, Neugebauer H, Wartenberg KE, et al. Triage and allocation of neurocritical care resources during the COVID 19 pandemic—a national survey. Front Neurol. 2020;11:609227. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.609227.

Burki T. Global shortage of personal protective equipment. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(7):785–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30501-6.

Cohen J, Rodgers YVM. Contributing factors to personal protective equipment shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev Med. 2020;141:106263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106263.

Ahmed N, Davids R. COVID 19: are South African junior doctors prepared for critical care management outside the intensive care unit? Pan Afr Med J. 2021;40:41. https://doi.org/10.1160/pamj.2021.40.41.30134.

Aurrecoechea A, Kadakia N, Pandya JV, Murphy MJ, Smith TY. Emergency medicine residents’ perceptions of working and training in a pandemic epicenter: a qualitative analysis. West J Emerg Med: Integr Emerg Care Popul Health. 2023;24(2):269–78. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2022.9.57298.

Latham SR. Avoiding ineffective end-of-life care: a lesson from triage? Hastings Cent Rep. 2020;50(3):71–2. https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.1141.

Santini A, Messina A, Costantini E, Protti A, Cecconi M. COVID-19: dealing with ventilator shortage. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2022;28(6):652–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCC.0000000000001000.

Vinay R, Baumann H, Biller-Andorno N. Ethics of ICU triage during COVID-19. Br Med Bull. 2021;138(1):5–15. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldab009.

Basu S. Approaches to critical care resource allocation and triage during the COVID-19 pandemic: an examination from a developing world perspective. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2021;14:5. https://doi.org/10.1850/jmehm.v14i5.5652.

Battisti D, Picozzi M. Deciding the criteria is not enough: moral issues to consider for a fair allocation of scarce ICU resources. Philosophies. 2022;7(5):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies7050092.

Ćurković M, Brajković L, Jozepović A, Tonković D, Župan Ž, Karanović N, et al. End-of-life decisions in intensive care units in Croatia—pre COVID-19 perspectives and experiences from nurses and physicians. J Bioeth Inquiry. 2021;18(4):629–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-021-10128-w.

Jöbges S, Vinay R, Luyckx VA, Biller-Andorno N. Recommendations on COVID-19 triage: international comparison and ethical analysis. Bioethics. 2020;34(9):948–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12805.

Craxi L, Vergano M, Savulescu J, Wilkinson D. Rationing in a pandemic: lessons from Italy. Asian Bioeth. 2020;12(3):325–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41649-020-00127-1.

Tian YJA. The ethical unjustifications of COVID-19 triage committees. J Bioeth Inq. 2021;18(4):621–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-021-10132-0.

Donkers MA, Gilissen V, Candel M, van Dijk NM, Kling H, Heijnen-Panis R, et al. Moral distress and ethical climate in intensive care medicine during COVID-19: a nationwide study. BMC Med Ethics. 2021;22(1):12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-021-00641-3.

Semler L. Operationalizing scarce resource allocation: a lived experience. J Hosp Ethics. 2022;8(2):64–72.

Naidoo R, Naidoo K. Prioritising “already-scarce” intensive care unit resources in the midst of COVID-19: a call for regional triage committees in South Africa. BMC Med Ethics. 2021;22(1):28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-021-00596-5.

Krishnan JK, Shin JK, Ali M, Turetz ML, Hayward BJ, Lief L, et al. Evolving needs of critical care trainees during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. ATS Sch. 2022;3(4):561–75. https://doi.org/10.3419/ats-scholar.2022-0026OC.

Mastoras G, Farooki N, Willinsky J, Dharamsi A, Somers A, Gray A, et al. Rapid deployment of a virtual simulation curriculum to prepare for critical care triage during the COVID-19 pandemic. CJEM. 2022;24(4):382–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43678-022-00280-6.

Coghlan N, Archard D, Sipanoun P, Hayes T, Baharlo B. COVID-19: legal implications for critical care. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(11):1517–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15147.

Marckmann G, Neitzke G, Schildmann J, Michalsen A, Dutzmann J, Hartog C, et al. Decisions on the allocation of intensive care resources in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic clinical and ethical recommendations of DIVI, DGINA, DGAI, DGIIN, DGNI, DGP, DGP and AEM. German version. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2020;115(6):477–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00063-020-00708-w.

Sprung CL, Joynt GM, Christian MD, Truog RD, Rello J, Nates JL. Adult ICU triage during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: who will live and who will die? Recommendations to improve survival. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(8):1196–202. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0000000000004410.

Altman MC. A consequentialist argument for considering age in triage decisions during the coronavirus pandemic. Bioethics. 2021;35(4):356–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12864.

Moore B. Dying during Covid-19. Hastings Cent Rep. 2020;50(3):13–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.1122.

Rao A, Kelemen A. Lessons learned from caring for patients with COVID-19 at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2021;24(3):468–71. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2020.0251.

Mercadante S, Gregoretti C, Cortegiani A. Palliative care in intensive care units: why, where, what, who, when, how. BMC Anesthesiol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-018-0574-9.

Orfali K. What triage issues reveal: ethics in the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy and France. J Bioeth Inq. 2020;17(4):675–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-020-10059-y.

Janwadkar AS, Bibler TM. Ethical challenges in advance care planning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Bioeth. 2020;20(7):202–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2020.1779855.

Acknowledgements

This review is to contribute towards a degree award (Honours) for the lead author (ES) as part of their Bachelor of Medicine/Bachelor of Surgery degree. The authors would like to acknowledge Stephen Anderson (SA) for their assistance in putting together the search criteria.

Funding

There is no funding for this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ES wrote the main manuscript text and prepared the figures and tables. NK participated in individual screening of eligible reports by title/abstract as an independent reviewer. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, E., Kulasegaran, N., Cairns, W. et al. Physician experiences of critical care triage during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. Discov Health Systems 3, 30 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-024-00086-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250-024-00086-6