Abstract

Purpose

The immediate impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) visiting restrictions for family members has been well-documented. However, the longer-term trajectory, including mechanisms for support, is less well-known. To address this knowledge gap, we aimed to explore the post-hospital recovery trajectory of family members of patients hospitalised with a critical care COVID-19 admission. We also sought to understand any differences across international contexts.

Methods

We undertook semi-structured interviews with family members of patients who had survived a COVID-19 critical care admission. Family members were recruited from Spain and the United Kingdom (UK) and telephone interviews were undertaken. Interviews were analysed using a thematic content analysis.

Results

Across the international sites, 19 family members were interviewed. Four themes were identified: changing relationships and carer burden; family health and trauma; social support and networks and differences in lived experience. We found differences in the social support and networks theme across international contexts, with Spanish participants more frequently discussing religion as a form of support.

Conclusions

This international qualitative investigation has demonstrated the challenges which family members of patients hospitalised with a critical care COVID-19 admission experience following hospital discharge. Specific support mechanisms which could include peer support networks, should be implemented for family members to ensure ongoing needs are met.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This international qualitative investigation has demonstrated the challenges which family members of patients hospitalised with a critical care COVID-19 admission experience following hospital discharge. Support mechanisms such as peer support networks should be considered for family members to ensure ongoing needs are met. |

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had a profound impact on critical care services internationally [1]. Services and clinicians adapted care delivery rapidly to optimise clinical outcomes [2, 3]. One modification implemented to reduce the transmission of the virus was family visitation restrictions. Hospital visiting was often completely prohibited or restricted, with a move to virtual visiting [4, 5]. These restrictions were in direct contrast to pre-pandemic practice, where critical care visitation aspired to an ‘open model’, in which family members could visit in a family centred manner and actively participate in decision making and care delivery [6, 7].

This change in practice is known to have negatively impacted critical care staff alongside family members of patients hospitalised with COVID-19 [8, 9]. For example, studies have demonstrated that family members of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 disease, as compared with other causes of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), were at a greater risk of developing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) at 90 days following intensive care unit (ICU) discharge [10]. Although there is now a body of literature emerging around the immediate challenges for family members, the longer-term trajectory, including mechanisms for support, have been less well-documented.

To address this knowledge gap, we utilised qualitative enquiry with data from three European sites, to explore the recovery trajectory of family members of patients hospitalised with a critical care COVID-19 admission following hospital discharge. We also sought to understand any differences across international contexts.

Methods

This study was approved by Liverpool Central Research Ethics Committee (17/NM/0199) (UK approval) and the Hospital Clínic of Barcelona Medical Research Ethics Committee (HCB/2021/1115) (Spanish approval). All participants provided informed consent.

Design and setting

We undertook individual semi structured interviews with family members following a hospital discharge, which involved a COVID-19 critical care admission. Qualitative inquiry was used to address the study aims as we wished to develop an in-depth understanding of participant experience. A family member was defined as a person who was in the role of Next of Kin for a patient admitted to critical care during the COVID-19 pandemic. We identified one member of each family unit to participate in this study. However, in the United Kingdom (UK) two family members of the same patient asked to participate in the study on initial approach and both were included in this analysis.

Family members of patients admitted with COVID-19 to three different hospital sites were recruited (two in the UK and one in Spain) to understand if family experiences differed across international contexts. Details of the international policy related to hospital visitation is provided in electronic supplementary material (ESM) S1. Interviews were undertaken in the local language and translated into English. In the UK, family members were recruited via attendance at an ICU recovery service. Family members who attended the service, who were recruited within an existing study for outcomes following COVID-19, were invited to participate in an interview. During the follow-up appointment for this existing study, family members were asked if they would be interested in participating in this qualitative study. If they did wish to participate, they were contacted by the research team (JM), where more information was given, and a time and date set for interview if appropriate.

In Spain, survivors of a COVID-19 critical care admission were contacted by phone and asked about permission to contact their family members. Information and informed consent were sent and obtained via email. We recruited family members of patients between 18 and 32 months following hospital discharge.

We utilised a purposive sampling approach to recruitment across each site to capture a sample which could answer the research objectives. We considered the characteristics of the participants and sought diversity in age, gender and relationship when recruiting family members.

Owing to the large geographical recruitment area of family members, telephone interviews were selected as the optimal method of data collection. Telephone interviews have been successfully used to collect ICU family experience data previously [11, 12]. A semi-structured topic guide was developed a priori and was informed by the literature in the field and iterative discussions with the research team (ESM S2); questions were open ended, and participants were encouraged to explore issues they considered relevant. Although the focus of these interviews and this analysis was on post-hospital outcomes, to fully understand the journey, the topic guide also included the following themes: ICU admission, ICU stay and in-hospital recovery. Throughout the interviews additional prompts were included; these prompts specifically delineated the experience of relatives in the post-hospital discharge period. Data were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Demographic data were self-reported and included sex, age, and relationship with the patient. Patient demographic data were collected from local information systems. Approval for this linked data collection was obtained within the ethics approval.

We obtained the socio-economic status of all patients included in this study. In Spain this was obtained using the Socio-Economic Index (IST). The IST is a synthetic index tool for small geographical areas in Spain. It summarizes in a single value, various socio-economic characteristics of the population. The index includes information on the employment situation, educational level, immigration and income of all the people who reside in each territorial unit. This tool presents each area on a scale of 1 to 10; 10 represents the highest levels of deprivation and 1 the lowest [13].

As both of the UK sites were in Scotland, socio-economic status was evaluated via the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD). The SIMD is a ranking index based on postcode of residence, which identifies neighbourhood socio-economic deprivation. Similar to the IST, each area of residence presents relative deprivation as a decile, with 1 representing areas of greater socio-economic deprivation [14].

Recruitment of new participants continued until data saturation was reached, that is, no new themes emerged from the interviews. Following regular discussion with the research team (KP, PC, JM) saturation was deemed to be achieved at the 19th interview. NKB, an experienced qualitative researcher, who was not directly involved in data collection for this study, also participated in these meetings to provide guidance in relation to data saturation and data analysis.

Interviews were arranged and conducted by experienced qualitative researchers at each site, who were also ICU clinicians (JM and CC). During the data collection phase, those undertaking interviews met regularly with other members of the research team and reflected on emergent themes. This step aimed to guard against unconscious bias and prevent narrowing the scope of the interviews artificially (before data saturation was obtained).

Data analysis

The study design used a thematic content analysis approach based on Miles and Huberman’s framework [15]. Five key steps were included in the data analysis process. First, the primary analysis team (JM and KP) undertook preliminary sweeps of the data to familiarize themselves with the content and develop initial coding. No pre-set or a priori codes were utilised. Second, a coding framework was created to describe and interrogate the recovery trajectory from the family members perspective. At this stage, any differences in the data generated were examined, for example, international differences. Third, the initial coding was grouped under key themes and iteratively checked across each transcript. Fourth, two researchers (JM and KP) defined and classified the key themes presented within this analysis. Finally, the primary analysis team reviewed the conceptual model and created and extracted quotations to support the thematic analysis, which included discussion with the wider analytical team (PC, NKB, KP and JM). An audit trail was maintained to demonstrate and delineate decision making. Data analysis took place between December 2022 and March 2023.

The Consolidated Reporting of Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist was used to report findings (ESM S3) [16].

Results

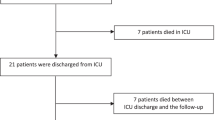

Across the three international sites, 21 family members were invited to participate in this study. Two people declined and 19 family members agreed to participation in this qualitative study. All interviews were undertaken in the participants home, via telephone and each interview lasted between 20 and 90 min. Of those interviewed, 83% of participants were spouses or partners. The characteristics of family members involved are presented in Table 1 alongside acute illness characteristics of their relatives’ ICU admission.

The primary aim of this analysis was to explore the long-term recovery trajectory of family members of patients hospitalised with a critical care COVID-19 admission. We also sought to understand any differences in experiences across international contexts. In relation to these aims, we derived four themes: changing relationships and carer burden; family health and trauma; social support and networks and differences in lived experience. Following a robust examination of the two international contexts, we found differences in the ‘social support and networks’ theme. The three remaining themes were similar across the two contexts. Delineation of these differences, alongside a detailed explanation of each theme are presented below. A selection of representative quotes across international sites are presented in Table 2.

Changing relationships and carer burden

Participants discussed how unresolved care needs following hospital discharge caused significant new carer burden. Various forms of ongoing physical and cognitive disability following COVID-19-related critical illness resulted in family members adopting an informal caregiver role. One participant from Spain described ongoing care needs:

‘This affected his mobility, which left him with everything from the waist to the foot as if he were insensitive, affecting his nerves. It has been a long two years and 100% has not been solved.’

This new carer burden described by participants was often exacerbated by a lack of medical and psychosocial follow-up available following hospital discharge. Participants described how basic support would have alleviated some of the challenges encountered during the initial discharge period:

‘I think it would have been helpful if someone, at the very least, taught us how to manage someone else's frustration when they're unwell, can't do the things they could do before, or are physically impaired... I think that aspect we would have appreciated it.’

Ongoing social isolation also caused challenges for family members. Previous social networks which would have been relied upon to support many aspects of recovery and adaptation, could not be relied upon due to ongoing social distancing measures. This caused further burden for the participants and in some instances, distress:

‘It was hard when I was on my own. There was one day I came screaming into the kitchen, screaming into myself… I had to cut his food up. I had to dry him. I had to bathe him. I had to shower him. I had to clothe him… I ran into the kitchen and started silently screaming…there were tears running down my face.’

Unclear infection control information also caused distress and changes in how families interacted with their loved one following hospital discharge. For example, one participant described their fear of showing affection with their loved one (and vice versa) due to ongoing worry around infection control and the impact that this had on their relationship:

‘But nothing was like you kept seeing it portrayed on TV. Somebody coming out of the COVID wards and somebody coming and giving them a hug. You know the family were so delighted. That just didn’t happen with us. Because I was told I wasn’t to go near him for two weeks… When he was coming off the ambulance, he said are we allowed to hug? Well they have told us that we have not to. You know, that we have not to go near one another. So this, I said, this seems very awkward and unnatural. You know? But it was what we had been told to do. It just didn’t seem, It wasn’t the way that you were seeing everything on the TV.’

Family health and trauma

Across international contexts, participants described the impact that the critical care COVID-19 admission of their family member had on their own health and the trauma and emotional challenges that this had brought. This impact on both physical and mental health was often compounded by the fact that many family members themselves had COVID-19 and were required to act as a primary caregiver while still recovering from their own acute illness:

‘I have lots of mobility issues, bending down is just impossible. I feel dizzy. I have fairly limited balance. So there are several issues, also recovering from COVID myself… It’s very difficult for me.’

Ongoing trauma was also present for some participants interviewed due to guilt, as they had exposed their family members to COVID-19. As well as the ongoing physical health problems, this also caused emotional distress for some:

‘I had COVID in the very beginning… I then obviously gave it to [my spouse]… I keep saying, God forbid if something had happened to him, I would I have blamed myself’

A number of participants described mental health problems, which for many, were ongoing at the time of interview. These mental health issues were often related to the acute stress encountered during the hospitalisation process and the long-term consequences of critical illness for their loved one:

‘Psychologically it was very hard, very hard. And then there, well, I fell into depression a little bit, right? After the stress… felt sadder, lower.’

Social support and faith

Across the interviews participants described the importance of social support following the discharge of their family member from the hospital setting. This support included other friends and families, alongside neighbours and colleagues. This often crucial support, was multi-faceted and included emotional support as well as more practical assistance. For example, one participant described how their neighbour had dropped off shopping to their family home:

‘… We were literally on our own, because… we were still in lockdown. So there was nobody who could come to the house. My next door neighbour was dropping in shopping for me, and they were leaving it at the back door for me… Other than that, we didn’t have any help, you know because we were totally on our own.”

However, some participants also described the absence of social support following hospital discharge. This was worsened by ongoing ‘lockdown’ measures which were still in place internationally, as patients were being discharged from the hospital. These laws meant that the support available to survivors was limited to those in their household. This had a profound impact on the participants in this study:

‘The situation was stressful. I had to become a dad, mum, worker, friend and everything, because I don’t have family here. At that time my daughter was 8 years old. I have my son the oldest, who was a little older than her. I had to be home, work, attending the hospital…everything. It was stressful.’

Participants also described the importance of faith during both the hospital encounter as well as during the immediate hospital discharge period. Analysis demonstrated that this concept differed across international contexts. Within the Spanish context, faith-based religion and spirituality was a crucial source of support for many of the participants interviewed. For example, one participant described the importance of faith during the experience:

‘…have full confidence in the one above, today we are, tomorrow we are not. It’s that clear. Faith moves mountains. I was convinced he was coming back and he came back.’

Across the UK interviews, participants described faith in the context of the National Health Service (NHS). Participants discussed the faith that they had in the NHS, and the staff who worked in this system, to take care of their family member. For many this was an important source of support and reassurance:

‘Believe in the NHS. Just keep believing.’

Differences in lived experience

Perceived differences in lived experiences were important to the family members interviewed. Participants highlighted that it was difficult to disengage from widespread media coverage of the pandemic, which often included stark attention to the critical care environment. This included watching news coverage of patients being discharged home from hospital. Media coverage included celebratory moments of COVID-19 survivors leaving hospital; however, participants in this study described a different reality. For example, one participant described picking her husband up from hospital and the mixed emotions this brought:

‘ It was a shock, a total shock. Because… he hadn’t been shaved in the neck and just, it made him look older. His hair was longer, he had lost about three stone. He just looked petrified. He had the Zimmer frame. When I got into the car, he’s not an emotional person, he’s not an affectionate person. So when he got into the car, I just broke my heart. I was just sobbing and sobbing and sobbing.’

Another participant described the reality of her husband being dropped off by ambulance, a stark difference in the experiences often portrayed in the media:

‘…It must have taken him about half an hour to get him from the ambulance up the stairs. I had to put a chair in the hall as soon as he came in. I had to sit him there and he said, he will need to sit there for a good half an hour before he can move, because he won’t be able to move anywhere, because he was so done in. It was as simple as.’

There was also a perceived difference in how family members and survivors understood the hospitalisation. Survivors could not remember details of the hospitalisation experience. This caused ongoing issues as family members could not support patients who may have been dealing with problems related to the hospitalisation (i.e., flashbacks, distressing memories as well as ongoing physiological needs). This difference in lived experience led to emotional upset for both family members and survivors. One family member from Spain described their experience:

‘When my husband came home we had to explain everything, how it had been, what had happened during the whole period he was in the ICU… He entered the ICU and then remembers nothing else. There were some brushstrokes left, it seems to me, from when he began to wake up. Then we had to explain everything to him patiently, repeat it. And that was to relive everything and we cried and cried.”

Discussion

This multi-centre, international qualitative investigation sought to understand the trajectory of family members of patients hospitalised with a critical care COVID-19 admission. It has demonstrated this group of family members experienced similar problems to those of family members of patients hospitalised in critical care without COVID-19, such as increased or new carer burden and mental health issues [17, 18]. However, there also appeared to be unique problems in this specific cohort such as profound social isolation and gaps in tacet knowledge about the hospitalisation due to visitation restrictions (Fig. 1). Interestingly coping strategies differed internationally in relation to spirituality and faith.

Previously published evidence has shown that family members of COVID-19 survivors have elevated levels of symptomology such as PTSD in the 90 days following discharge in comparison with those not related to a COVID-19 admission [10]. This present international study extends these findings by showing a range of challenging problems which differ in nature to those previously described. These findings have implications for how we offer advice, support and interventions in future research. Previous interventional research for family members following discharge from critical illness has focussed on supporting issues, such as mental health and carer burden—which were considerable in this cohort too [19]. Interventions such as lay summaries and peer support groups may be beneficial for the specific issues raised by family members such as social isolation and a lack of understanding about the in-hospital journey [18,19,20]. Evidence has shown that it is feasible to deliver interventions such as lay summaries to delineate the hospital journey and critical illness narrative. Moreover, the digital transformation of peer support has been widely adopted internationally [20,21,22]. Future research should consider how these complex interventions could be integrated into ongoing care and tested robustly.

Although this study examined the post-hospital journey of family members of COVID-19 survivors, there is clear learning for the broader, non-COVID-19 family cohort. It is crucial that any intervention designed to support outcomes following critical illness also considers the wider social context and the entire family unit. Moreover, the consideration of the international context and resources available are important in determining the range and scope of care that can be delivered. There is limited work examining post-ICU care and outcomes in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMIC) [23]; future research should examine this variation and how long-term outcomes can be supported across international contexts.

This study suggests the nature of faith which provided reassurance and support during both the acute encounter and the initial post-hospital recovery period, differed internationally. Spanish family members commonly described the importance of ‘traditional’ religious spirituality as a support mechanism, whereas UK participants more frequently described faith in the NHS and the people who provided care. This difference likely reflects geopolitical variation in faith and religiosity across different international contexts [24]. However, it highlights that this spirituality and the wider positive benefits which it might provide (i.e., a reduction in stress facilitated by hope), are important across the critical illness recovery continuum for patients and family members. Previous research has shown that spirituality and faith can play a significant role in the recovery process following critical illness [25] and both social determinants of health and spirituality have been identified as high priority areas for research in critical illness survivors [26]. Future research, therefore, should focus on any potential unmet needs in relation to spirituality and examine any relationships that spirituality and faith may have with outcomes.

This work has several strengths. It utilised an international cohort of participants to understand the long-term trajectory of family members. Moreover, it utilised a robust approach to analysis, utilising established methodology. There are also limitations to these data. Although we took steps to include a diverse sample, our sample might not be representative of all family members and thus other experiences could have been missed. We also have limited data available on other contextual differences which might have impacted recovery, for example, the financial situation of families. Moreover, although we included data on the socio-economic status of patients, this might not reflect the situation of family members. Finally, it is important to recognise that other factors are likely to have contributed to the outcomes described within the present study, and that these data are not representative of all international settings.

Conclusion

This novel international qualitative investigation has demonstrated the challenges which family members of patients hospitalised with a critical care COVID-19 admission experience in the longer term. Our findings suggest that interventions such as peer support and hospital journey tools including lay summaries might be particularly effective for this cohort and should be examined in future research.

Availability of data and materials

A de-identified data set and the study protocol may be made available to researchers with a methodologically sound proposal, to achieve the aims described in the approved proposal. Data will be available upon request following article publication. Requests for data should be directed at jm2565@medschl.cam.ac.uk to gain access.

References

Arabi YM, Azoulay E, Al-Dorzi HM et al (2021) How the COVID-19 pandemic will change the future of critical care. Intensive Care Med 47(3):282–291

Mateen BA, Wilde H, Dennis JM et al (2021) Hospital bed capacity and usage across secondary healthcare providers in England during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: a descriptive analysis. BMJ Open 11(1):e042945

Dennis JM, McGovern AP, Vollmer SJ, Mateen BA (2021) Improving survival of critical care patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in England: a national cohort study, March to June 2020*. Crit Care Med 49(2):209–214

Rose L, Yu L, Casey J et al (2021) Communication and virtual visiting for families of patients in intensive care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a UK national survey. Ann Am Thorac Soc 18(10):1685–1692

Valley TS, Schutz A, Nagle MT et al (2020) Changes to visitation policies and communication practices in Michigan ICUs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 202(6):883–885

Nassar Junior AP, Besen B, Robinson CC, Falavigna M, Teixeira C, Rosa RG (2018) Flexible versus restrictive visiting policies in ICUs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 46(7):1175–1180

Hart JL, Taylor SP (2021) Family presence for critically ill patients during a pandemic. Chest 160(2):549–557

McPeake J, Kentish-Barnes N, Banse E et al (2023) Clinician perceptions of the impact of ICU family visiting restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic: an international investigation. Crit Care 27(1):33

McPeake J, Shaw M, MacTavish P et al (2021) Long-term outcomes after severe COVID-19 infection: a multicenter cohort study of family member outcomes. Ann Am Thorac Soc 18(12):2098–2101

Azoulay E, Resche-Rigon M, Megarbane B et al (2022) Association of COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome with symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in family members after ICU discharge. JAMA 327(11):1042–1050

Kentish-Barnes N, Cohen-Solal Z, Morin L, Souppart V, Pochard F, Azoulay E (2021) Lived experiences of family members of patients with severe COVID-19 who died in intensive care units in France. JAMA Netw Open 4(6):e2113355-e

Haines KJ, Hibbert E, Leggett N et al (2021) Transitions of care after critical illness-challenges to recovery and adaptive problem solving. Crit Care Med 49(11):1923–1931

(IST) Íst. Institut d’Estadística de Catalunya (idescat), Generalitat de Catalunya. 2020. http://www.idescat.cat/. Accessed 20 Jul 2023

Government S. Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation 2020

Miles MB, Huberman AM (1994) Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. Sage, New York

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19(6):349–357

McPeake J, Devine H, MacTavish P et al (2016) Caregiver strain following critical care discharge: an exploratory evaluation. J Crit Care 35:180–184

Sevin CM, Boehm LM, Hibbert E et al (2021) Optimizing critical illness recovery: perspectives and solutions from the caregivers of ICU survivors. Crit Care Explor 3(5):e0420

Eaton TL, Sevin CM, Hope AA, et al. Evolution in care delivery within critical illness recovery programs during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Ann Am Thorac Soc 0(ja): null

Hope AA, Johnson A, McPeake J et al (2021) Establishing a peer support program for survivors of COVID-19: a report from the critical and acute illness recovery organization. Am J Crit Care 30(2):150–154

McPeake J, Henderson P, MacTavish P et al (2022) A multicentre evaluation exploring the impact of an integrated health and social care intervention for the caregivers of ICU survivors. Crit Care 26(1):152

Barreto BB, Luz M, Rios MNdO, Lopes AA, Gusmao-Flores D (2019) The impact of intensive care unit diaries on patients’ and relatives’ outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 23(1):411

Pieris L, Sigera PC, De Silva AP et al (2018) Experiences of ICU survivors in a low middle income country—a multicenter study. BMC Anesthesiol 18(1):30

Zimmer Z, Rojo F, Ofstedal MB, Chiu CT, Saito Y, Jagger C (2018) Religiosity and health: a global comparative study LID—100322. SSM Popul Health 7:100322

Eaton TL, Scheunemann LP, Butcher BW, Donovan HS, Alexander S, Iwashyna TJ (2022) The prevalence of spiritual and social support needs and their association with postintensive care syndrome symptoms among critical illness survivors seen in a post-ICU follow-up clinic. Crit Care Explor 4(4):e0676

Mikkelsen ME, Still M, Anderson BJ et al (2020) Society of critical care medicine’s international consensus conference on prediction and identification of long-term impairments after critical illness. Crit Care Med 48(11):1670–1679

Acknowledgements

The research team would like to thank the family members who took time to participate in these interviews.

Funding

This study was funded by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Family partnership Award (2020). JM is funded via a Fellowship from The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute (University of Cambridge (PD-2019-02-16).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JM and KP had full access to all study data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data analysis. JM and KP conceptualized and designed the study. All authors contributed to the analysis and/or interpretation of the data. JM drafted the original manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

EA reported receipt of personal fees (lectures) from Pfizer, Gilead, Baxter, and Alexion; and institutional research grants from Merck Sharp and Dohme, Pfizer, Baxter, and Alexion outside the submitted work.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by Liverpool Central Research Ethics Committee (17/NM/0199) (UK approval) and the Hospital Clínic of Barcelona Medical Research Ethics Committee (HCB/2021/1115) (Spain approval).

Consent for publication

All participants provided written informed consent for participation in this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McPeake, J., Castro, P., Kentish-Barnes, N. et al. Post-hospital recovery trajectories of family members of critically ill COVID-19 survivors: an international qualitative investigation. Intensive Care Med 49, 1203–1211 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-023-07202-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-023-07202-9