Abstract

Background

Public Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) education is important to increase the survival rate of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). In this study, we survey local healthcare personnel in China who met the requirements of becoming public CPR instructors to assess their level of knowledge and attitudes toward teaching CPR.

Materials and Methods

To find qualified public CPR instructors among the local healthcare personnel, we ran three training sessions between March 2018 and December 2018. We held three courses on selecting public CPR instructors from the local healthcare personnel (n = 496). We also surveyed candidates for public CPR instructors before making our final choice. The selected instructors were retrained for a single day in December 2021. The necessary information was exchanged with the members of the passing group, and the maintained valuables were investigated.

Results

Public CPR instructors certified 428 cases (86.49%) after the final exam. The results showed that the emergency group had a higher success rate than the non-emergency group (control group) (175, 90.7% vs. 253, 83.8%; P = 0.042). Here, we conducted a binary logistic regression analysis to determine the relationship between 15 survey variables and the passing rate. The variables, such as financial incentives, prior automatic external defibrillator (AED) training, and younger age were independently affected by being public CPR instructors. Despite this, 246 instructors (57.9%) still attended the retraining courses in 2021, with significantly more instructors in the emergency group than those in the non-emergency group (111, 64.5% vs. 135, 53.4%; P = 0.022). Furthermore, the instructors who were not incentivized financially were less likely to switch between the emergency and non-emergency groups (96, 79.33% vs. 116, 86.56%; P = 0.990).

Conclusion

The Chinese emergency team can serve as a model for the local healthcare personnel by training and leading a group of volunteer CPR instructors. Our research has practical implications for China's national CPR education policy by informing the scheduling of regional public CPR education programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

The most time-sensitive medical emergency is a out of hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). The survival rates from OHCA drop by 10% for every minute that the treatment is delayed as reason that its gold treatment time is 3–5 min [1]. The most important factor in reducing OHCA mortality is the availability of bystander automatic external defibrillators (AEDs) and bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) [2]. Although over 550,000 individuals in China experience cardiac arrest each year [3], most of them die before the ambulances can arrive [4], as the average response time for ambulances in China is 13–20 min [5]. However, numerous “sudden death” caused by OHCA has sparked widespread discussion on improving the survival rate in China [6]. Public CPR training is significantly less common in developing countries like China and India than in the West [7]. CPR training correlates directly with the prevalence of bystander CPR. Establishing a team of public CPR instructors from the local healthcare personnel is one of many interventions intended to increase the number of people trained in bystander CPR and AED. More than half of the adult respondents (57%) in Hong Kong who had already accepted their knowledge of CPR but still needed to learn how and when to perform it [8]. Despite 30 years of development in China's emergency services sector, only a tiny fraction of the country's general population (1%) has been licensed in CPR. Establishing additional certified public education on bystander CPR and the use of AED by emergency staff is crucial [9]. We must take more measures to improve training and willingness to perform CPR in several parts of China [10], despite these measures being reported in Tianjin and Wuhan [11, 12].

The bystander CPR rates and accurate CPR knowledge could be increased with a five-year regional intervention in Japan that included legislation encouraging public involvement, standardizing CPR education programs, training CPR instructors, and installing supporting organizations [13]. After these interventions, a significant increase was noted in the number of people who learned CPR, from 36.2 to 55.1%. Providing high-quality CPR training to the public in China was the first step in the regional intervention, while the first step in China was to form a team of formal public CPR instructors [14]. Thus, creating a program to select public CPR instructors among healthcare personnel is critical. Hence, emergency medical professionals must make further efforts toward accumulating a more qualified pool of CPR instructors [15]. Some challenges, nonetheless, may appear in the transition from healthcare personnel to public CPR instructors.

In this study, we conducted a survey of the knowledge and attitudes of healthcare professionals to identify the factors that are associated with being formal instructors.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Population

During March 2018 and December 2018, we conducted three courses on selecting public CPR instructors from among local healthcare personnel.

This program included a theoretical component (lasting 120 min) and a practical component (lasting 60 min), where the participants learned and practised bystander CPR and used an AED. The requirements for enrolling in the course are as follows:

-

(1)

An enthusiasm for teaching bystander CPR and AED in public;

-

(2)

Work experience in a local healthcare setting;

-

(3)

Prior information to the participants about needing to complete a 180-min training program.

-

(4)

Every participant in the selection process was required to sign a consent form authorizing the collection of the survey data and completion of the survey in its entirety within 20 min (Additional file 1: Questionnaire). If a participant dropped out of the study or refused to provide the information, it did not include their questionnaire in the final analyses.

The study was approved by the Institutional Human Ethics Committee of People’s Hospital of Shenzhen Baoan District Shenzhen, the Second Affiliated Hospital of Shenzhen University (BYL 2018JD066).

2.2 Questionnaire

The participant’s knowledge and attitudes were evaluated using a structured questionnaire developed by five resuscitation medicine experts.

It consisted of 15 questions spread across three sections to collect data. Section 1 questions 1–4 explored the participant’s essential characteristics (i.e., age, gender, service department, and CPR training frequency within one year). We also assessed the participants' knowledge about bystander-CPR, AED, and other emergencies in the section (Questions 5–12). We have also detailed the investigation of the participant’s attitudes toward being a public CPR instructor in Sect. 3 (Questions 13–15).The internal consistency alpha of the questionnaire is analysis in additional file 2.

2.3 Examination and Authentication

Two CPR experts conducted a final examination at the end of the selection course to ensure that the students had met the criterion of basic life support (BLS) as outlined in the 2015 American Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Cardiovascular First Aid Guideline Update [16]. The specialists were required to have AHA certifications for the BLS CPR requirement. The final credentials rate of every participant was objectively documented.

2.4 Subgroup Division Principles

There were two subgroups of all subjects: the emergency group, which included those who worked in the emergency system (i.e., pre-hospital care, international-hospital emergency, and intensive care unit) and the non-emergency group, which did not include those who worked in the emergency system (control group).

2.5 Rehabilitation Training at Three Years

To update the selected instructors to contemporize the 2020 American Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Cardiovascular First Aid Guideline [17], we held a 1-day retraining course in December 2021. We also exchanged information with members of the passing group and investigated the maintained valuables. Every instructor was assigned to two subgroups: the attending and non-attending groups.

2.6 Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as the case number’s mean ± standard deviation or percentage Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test was used to establish comparisons of quantitative variables based on whether their distribution is normal. We used X2 to determine comparisons of the categorical variables. It analyzed binary logistic regression to identify public CPR instructors' independent factors. P < 0.05 was regarded to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software package (version 20.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3 Results

3.1 Baseline Characteristics

A total of 496 participants had valid data for investigation. In Table 1, 428 (86.49%) cases passed the final exam and were awarded CPR certification by independent public CPR instructors, as shown in Table 1. We found that the passing proportion in the emergency group was higher than that in the non-emergency group (175, 90.7% vs. 253, 83.8%; P = 0.042). Physicians and nurses were in higher proportions in the emergency groups (48, 24.9% vs. 92, 30.5%; 142, 73.6% vs. 154, 51.0%; P = 0.001). Moreover, more numbers of staffers in the emergency group had accepted CPR training compared to those in the non-emergency group (> 5 times or 3–5 times within the past year, respectively: 40, 20.9% vs. 17, 5.8%; P = 0.001; 87, 45.3% vs. 106, 35.9%; P = 0.001).

3.2 Knowledge of Dealing with Emergency Events

Resuscitation experience from both the out-of-hospital (OHCA) (113, 58.2% vs. 42, 14.0%) and in-of-hospital cardiac arrests (IHCA) was higher among emergency instructors compared to those in their non-emergency counterparts (185, 95.4% vs. 197, 65.3%). Table 2 depicts that the emergency instructors had more experience with other types of emergencies, including traumatic hemorrhage (163, 83.5% vs. 109 cases, 36.1%; P = 0.001), suffocation (144, 74.2% vs. 65, 21.5%; P = 0.001), syncope (103, 53.1% vs. 35, 11.6%; P = 0.001), and epilepsy (154, 79.4% vs. 91, 30.1%; P = 0.001). Compared to instructors in the emergency group, those in the non-emergency group had significantly less AED training before taking our course (187, 96.4% vs. 239, 79.1%; P = 0.001). It is notable to mention that some instructors in both the emergency group (50, 25.90%) and the non-emergency group (112, 37.1%) have yet to correct their knowledge of the resuscitation strategy from A-B-C to C-B-A, which is a crucial condition laid down by the 2015 AHA Guideline [16].

3.3 The Attitude of Being a Public CPR Instructor

Table 3 shows that the two groups share similar perspectives on teaching CPR to the public: both value social accountability and hobby, and advertise healthiness in knowledge and designated duties. A significantly higher proportion of emergency group instructors prefer “part-time fees” as their motivation to partake in public CPR training (48, 24.7% vs. 43, 14.5%; P = 0.004). The emergency group instructors were likelier to prefer “one time each week” than in the non-emergency group (74, 38.1% vs. 73, 24.2%; P = 0.001).

3.4 Independent Factors Being a Resuscitation Instructor

We performed binary logistic regression analysis to assess the association between 15 survey variables and the outcome of “passing the final test.” Consequently, younger age, previous training on AED, and financial motivation were observed to independently affect being public CPR instructors (OR: 0.957, 95% CI [0.925–0.990]; OR: 2.698, 95% CI [1.441–5.050]; OR: 3.176, 95% CI [1.231–8.191]) (Table 4).

3.5 Factors for Maintaining Being a Resuscitation Instructor

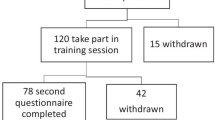

In 2021, 246 (57.9%) instructors continued to participate in the retraining courses, with significantly more numbers of attendees belonging to the emergency group than to the control group shown in Fig. 1A (111,64.5% vs. 135, 53.4%; P = 0.022). Attendees were less likely to be financially motivated than the non-attendees, as shown in Fig. 1B (46, 17.47% vs. 48, 25.69%; P = 0.040). Furthermore, instructors who were not financially motivated to offer the same enthusiasm in either the emergency or non-emergency group gave identical responses (96, 79.33% vs. 116, 86.56%; P = 0.990). However, those in a non-emergency group with economic stimulus were easier to abandon, with 75.63% in Fig. 1C.

The portion of instructors who attended the retraining courses in 2021. A The ratio of attending instructors in the emergency group and in the non-emergency group. B Financial motivation occupied a lower rate in the attending group relative to that in the non-attending group. C Instructors without any financial motivation offered the duplicate zealous in the emergency or the non-emergency group

4 Discussion

Our initial report investigated the connection between influential factors and public CPR instructors from local healthcare personnel in China. It was observed that physicians and nurses are still the primary sources of instructors, with the maximum passing rate of 90% [18]. It was also found that the staffers in the emergency department have better knowledge and experience in CPR than in other departments. Several strategies have been proposed to improve the rate of AED use, such as optimising AED deployment strategies, using drones to transport the AEDs to the OHCA scene and using mobile applications to locate the nearest AED[19]. It is important to update the BLS education policy, as research by Ludovic Sturny et al. found that medical students had a greater understanding regarding BLS procedures than the general public [20]. While the results of our survey guarantee that the emergency department CPR instructors have undergone sufficient training to administer life-saving measures, they also showed that the most frequently selected instructors could benefit from a retraining course on the recent guidelines. Another finding highlighted the importance of age, prior AED training, and personal financial motivation to being a public CPR instructor. There are several reasons for this, some of which are listed below.

First, there is a correlation between a greater decline in resuscitation knowledge as one ages and a more extended response time on the final examination. Similar data from the United Kingdom demonstrated, in fact, that it becomes more challenging to memorize short-time courses with growing years. Thus, we needed to create a lengthy procedure for sweetening resuscitation, considering, processing, and revising the existing ability and skills from the tardy guidelines [21]. Based on survey results, we developed and delivered a one-day course to help public CPR instructors better articulate their understanding of the key concepts. Second, because of the stringent legal requirements, AED was not widely used across China [22]. It can be thus understood why some healthcare personnel yet to accept AED training, although they had been instructed to employ direct electrical defibrillation in hospitals. Prior AED training also had an independent correlation with the selection's success. Furthermore, for the medical staff member who is amenable to retraining at routine intervals, we suggest a re-education program that promotes the use of AED [23]. Similarly, as of June 12, 2022, 49 individuals had been successfully feted with AEDs seated in public locations following Shenzhen's “Public AED Program” launch in 2017. Further, recent research has suggested that, despite the inevitable delay, using a mobile App to monitor and control an AED's performance could improve its efficacy and safety [24].

Third, BLS operating costs are a common challenge; in the classroom setting, direct costs for those designed by the faculty need to be analyzed. Jordi Castillo believes that the blended-learning approach to BLS-AED courses can save money, primarily by reducing the cost of the instructors [25]. As the largest developing country, the budget of the Chinese medical system stands at a low level and warrants further financial support from the government [26]. It may also contribute to the association between a positive attitude induced by financial motivation and the passing rate in the final test. Similarly, China needs a coordinated national strategy for bystander CPR and AED training in the public. We have suggested creating a permanent organization to coordinate publicly funded CPR education. Fortunately, in this regard, we obtained financial sponsorship from the state of Baoan District, Shenzhen. Our nonprofit schooling in public CPR education had spread with growing numbers of certified first bystanders at 233,879 (5.23%) folk in the Baoan district [27]. According to the OHCA database in the Bao'an District, the bystander CPR rate has increased to 17.87%, and 1837 AEDs have been deployed, resulting in the OHCA survival rate rising to 5.12%.

However, there are several limitations in this analysis. First and foremost, the survey data may reflect only a tiny proportion of instructors because the number of instructors are expected to rise to 2600 at the end of December 2022. This data has been described in the preprint version; however, it has yet to be published [28]. Second, conducting an additional extensive assessment before and after the selected course would be helpful. Third, the conclusions we draw about our limited access to healthcare workers may hold true in other regions of China that are geographically isolated.

5 Conclusions

In summary, those who work in the emergency services are the best candidates to teach CPR to the general public. Interestingly, instructors without financial motivation will probably maintain long-period parties in public CRP education regardless of the factors such as age group, prior training in AED, or economic stimulus. Our data can be considered when scheduling local CPR education policy in China.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CPR:

-

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

- OHCA:

-

Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest

- AED:

-

Automatic External Defibrillator

- AHA:

-

American Heart Association

- BLS:

-

Basic Life Support

References

Bernard SA, Gray TW, Buist MD, et al. Treatment of comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with induced hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(8):557–63. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa003289.

Zègre-Hemsey JK, Bogle B, Cunningham CJ, Snyder K, Rosamond W. Delivery of automated external defibrillators (AED) by drones: implications for emergency cardiac care. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12170-018-0589-2.

Yan S, Gan Y, Jiang N, et al. The global survival rate among adult out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients who received cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-2773-2.

Xu F, Zhang Y, Chen Y. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation training in China current situation and future development. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(5):469–70. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2017.0035.

Yan K, Jiang Y, Qiu J, et al. The equity of China’s emergency medical services from 2010–2014. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16(1):10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0507-5.

Feng XF, Hai JJ, Ma Y, Wang ZQ, Tse HF. Sudden cardiac death in mainland China: a systematic analysis. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2018;11(11):e006684. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.118.006684.

Duber HC, Wollum A, Phillips B, et al. Public knowledge of cardiovascular disease and response to acute cardiac events in three cities in China and India. Heart. 2018;104:67–72. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2017-311388.

Cartledge S, Saxton D, Finn J, Bray JE. Australia’s awareness of cardiac arrest and rates of CPR training: results from the Heart Foundation’s HeartWatch survey. BMJ Open. 2020;10(1):e033722. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033722.

Feng XF, Hai JJ, Ma Y, Wang ZQ, Tse HF. Sudden cardiac death in mainland China: a systematic analysis. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2018;11(11):e006684. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.118.006684.

Lu C, Jin YH, Shi XT, et al. Factors influencing Chinese university students’ willingness to performing bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Int Emerg Nurs. 2017;32:3–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ienj.2016.04.001. (Epub 2016 the 8th of May PMID: 27166262).

So KY, Ko HF, Tsui CSY, et al. Brief compression-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation and automated external defibrillator course for secondary school students: a multischool feasibility study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10):e040469. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040469.

Mao J, Chen F, Xing D, et al. knowledge, training and willingness to perform bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation among university students in Chongqing, China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(6):e046694. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046694.

Moon S, Ryoo HW, Ahn JY, et al. A 5-year change of knowledge and willingness by sampled respondents to perform bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a metropolitan city. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0211804. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211804.

Wang L, Shi Z, Qu J. Compose a new chapter of cardiopulmonary resuscitation training with Chinese characteristics. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2018;30(12):1117–8. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-4352.2018.012.002.

Zhang W, Tao W, Wang C. The priority of emergency medicine is teaching people the basic skills of first aid. Chinese J Emerg Med. 2018;27(2):128–30. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2018.02.003.

Association. WHAT’S NEW & WHY Important changes in the 2015 AHA guidelines update. J Emerg Med Serv. 2016;41(3):27–35.

Craig-Brangan KJ, Day MP. Update: AHA guidelines for CPR and emergency cardiovascular care. Nursing. 2020;50(6):58–61. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NURSE.0000659320.66070.a9.

Semeraro F, Scapigliati A, Tammaro G, et al. Advanced life support provider course in Italy: a 5-year nationwide study to identify the determinants of course success. Resuscitation. 2015;96:246–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.08.006.

Delhomme C, Njeim M, Varlet E, et al. Automated external defibrillator use in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: current limitations and solutions. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2019;112(3):217–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acvd.2018.11.001.

Sturny L, Regard S, Larribau R, et al. Differences in basic life support knowledge between junior medical students and lay people: web-based questionnaire study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(2):e25125. https://doi.org/10.2196/25125.

Thorne CJ, Lockey AS, Kimani PK, et al. Advanced life support subcommittee of the resuscitation council (UK). e-learning in advanced life support-what factors influence assessment outcome? Resuscitation. 2017;114:83–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2017.02.014.

Zhang L, Li B, Zhao X, et al. Public access of automated external defibrillators in a metropolitan city of China. Resuscitation. 2019;140:120–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.05.015.

Abolfotouh MA, Alnasser MA, Berhanu AN, Al-Turaif DA, Alfayez AI. Impact of basic life-support training on the attitudes of healthcare workers toward cardiopulmonary resuscitation and defibrillation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):674. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2621-5.

Carballo-Fazanes A, Jorge-Soto C, Abelairas-Gómez C, et al. Could mobile apps improve laypeople AED use? Resuscitation. 2019;140:159–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.05.029.

Castillo J, Gomar C, Rodriguez E, Trapero M, Gallart A. Cost minimization analysis for basic life support. Resuscitation. 2019;134:127–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.11.008.

Ding J, Hu X, Zhang X, et al. Equity and efficiency of medical service systems at the provincial level of China’s mainland: a comparative study from 2009 to 2014. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):214. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5084-7.

Zhang W, Dou Q, Liang J, Tao W, Wang C. Government-led public emergency training: practice in Shenzhen Baoan. Chinese J Emergency Med. 2019;28(1):126–8. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2019.01.027.

J Lin, C Wang, Y Luo, W Zhang, W Tao, QL Dou, J Wei et al. Emergency staffers could guide local healthcare providers constructing a team of mass CPR instructors: a survey report of knowledge and attitudes from Shenzhen City, China. 2020. Research Square. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-15697/v1

Acknowledgements

The roles of the funding body in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, as well as in writing the manuscript should be declared. We thank all investigators for their excellent assistances in this clinical research.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from Shenzhen Key Medical Discipline Construction Fund, SZXK047; the High-level medical team of Shenzhen "Three Famous Medical and Health Project", SZSM201606067 and Key Laboratory of Emergency and Trauma (Hainan Medical University), Ministry of Education (Grant. KLET-201902). All sources of funding for the research reported should be declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JL participated in the study conception and drafting of the manuscript; CW, YL, WT, and JW abstracted the data collection and formal analysis; WZ and OD guided the data analysis and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest relevant to this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, J., wang, C., Luo, Y. et al. Study of the Variables of Local Healthcare Personnel Linked to Becoming a Formal Public CPR Instructor in Baoan, Shenzhen, China. Intensive Care Res 3, 123–130 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44231-023-00030-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44231-023-00030-x