Abstract

Introduction

Promoting physical activity (PA) at work effectively decreases the risk of chronic disease and increases productivity. Despite the well-established benefits of PA, only 24% of adults meet the PA Guidelines for Americans. Advancing a culture of health (COH) may improve employees’ physical activity levels. The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of workplace culture of health, gender, and depression on employee physical activity.

Methods

Employees (n = 12,907) across 14 companies voluntarily completed the Workplace Culture of Health (COH) Scale, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2), and questions on PA engagement. A logistic regression was performed to determine the effects of workplace COH, gender, and depression risk on the likelihood of engaging in 150 min of moderate to vigorous PA and in strength training 2 × per week.

Results

Workplace COH scores were associated with increased odds of PA engagement (OR = 1.058, p < 0.001). Further, gender and depression risk moderated the relationship between workplace COH and PA engagement (OR = 0.80, p = 0.026). For employees at risk for depression, an increase in COH scores was associated with higher PA for men, but not women. For employees not at risk for depression, an increase in COH scores was associated with higher PA for males and females.

Conclusion

Establishing a health-supportive workplace culture may increase PA, which is essential to improving population health. The differential findings by gender and depression risk illustrate the complexity of PA engagement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Rising rates of physical inactivity and sedentary behavior are causes for public health concern [4]. Physical activity (PA) is a modifiable health behavior known to increase the longevity of life, reduce the risk for chronic diseases, and improve cognitive function and functional health [26]. Approximately 10% of premature mortality and an estimated $117 billion in health care costs are associated with inadequate levels of PA [7, 8]. In addition to physical health benefits, PA has positive effects on mental health and psychological wellbeing [3]. Studies show that PA has benefits in improving depression symptoms compared to antidepressant medication [13]. In a study on over 1.2 million U.S. adults, individuals who engaged in 30 to 60 min of PA three to five times per week reported 43% fewer days of poor mental health, compared to individuals who did not exercise, even when controlling for confounding variables such as gender, race, age, income level, and exercise type [10]. Further, PA is correlated with positive psychological outcomes such as increased happiness, and higher levels of purpose in life ([44, 45]). Even modest increases in PA levels have been shown to reduce health risks such as mortality, type II diabetes, and heart disease [37, 42].

Despite these well-established benefits of PA, only 24% of adults in 2020 met the 2018 PA guidelines for Americans that indicate adults should engage in at least 150 min of moderate PA or 75 min of vigorous PA and engage in strength training twice per week [15]. In addition, researchers consistently found differences in PA and depression levels by gender, where males engage in high levels of PA and report lower rates of depression than females [25, 34]. Further, individuals with depression engage in less PA and more sedentary behavior than individuals without depression [28, 40]. However, individuals with mental illness may see the most benefit from regularly engaging in PA [43]. Increasing PA can substantially improve the health of all individuals.

Promoting PA in the workplace may benefit employees and employers [5, 6]. Most Americans utilize employer-sponsored health care, and associated costs for companies have risen dramatically [11]. Over 50% of Americans have a chronic physical or mental health condition, and studies show that over 90% of healthcare expenditures are for people with chronic conditions, which costs approximately $3.7 trillion annually [36]. In addition, employers incur additional indirect costs of unhealthy employees with productivity loss and absenteeism [1, 2]. A study on a large U.S. global financial services organization found that employees who engaged in at least 150 min of exercise per week had over $1000 less in healthcare costs compared to employees who engaged in less than 150 min of exercise [5]. Promoting PA in the workplace is an effective way to improve employee health by reducing chronic physical and mental health conditions.

Given existing evidence, employers are highly motivated to positively influence the health and health behaviors of their employees. Over 50% of employers offer a workplace health promotion program, with over 70% containing a PA component [33]. PA may influence work-related outcomes such as job performance through the accrual of physical, cognitive, and psychological resources [6]. Workplace PA interventions have also been shown to influence the health and wellbeing of participating employees [12]. However, many workplace health promotion programs designed to improve the health and wellbeing of employees may not be effective in reaching their employees [18]. Many of these programs target individual behavior change, which may not be as effective as population-level interventions [19].

Establishing a culture of supportiveness around health and wellbeing may promote healthy lifestyle choices and improve the effectiveness of workplace health promotion programs [17]. A workplace culture of health is defined as the combined influence of the social and physical environment on attitudes and behaviors related to health and wellbeing [31]. Prior research has shown that workplace culture of health is significantly related to improved employee health and wellbeing outcomes such as lower stress, high work engagement, reduced medical costs, and better emotional wellbeing [22, 30]. Studies have shown that providing policies that support PA, such as maintaining walking trails near an office, subsiding gym memberships, or providing access to exercise facilities, positively impacts PA levels [14, 41].

However, there is limited research on the direct relationship between employee perceptions of the workplace culture of health and PA. The purpose of this study was twofold: (1) to examine if workplace culture of health is a predictor of employee PA, and (2) to determine if gender and mental health risk moderate the effect of workplace culture of health on PA. The two research hypotheses are: (1) workplace culture of health significantly predicts employee PA levels, and (2) gender and depression risk moderates the relationship between workplace culture of health and employee PA. Depression is the most prevalent mental health conditions in employed populations and is the leading cause of global disability [23]. Understanding the influence of a culture of health on PA can help motivate employers to put resources into developing a more robust culture of health to help their employees develop consistent PA habits and address mental health concerns.

2 Methods

2.1 Sample and study design

The sample used for this study was from Virgin Pulse’s workplace culture of health assessment database. The culture assessment was administered to employees of consenting organizations between December 2018 and November 2019 via the Virgin Pulse online platform. Eighteen organizations expressed interest in participating and were given summary reports and wellbeing strategy recommendations after the completion of the survey. Employees from interested organizations completed the Workplace Culture of Health Scale and gave permission to use matched data from the employees’ Health Risk Assessment (HRA). The HRA is an instrument used to collect an employee’s health information, including biometrics and self-report data, typically provided by an independent third party through one’s employer. This HRA instrument also included a measure on depression and PA, respectively. Employees had approximately one month to complete the assessment and participation was voluntary. All participants were informed and consented to allow the use of the anonymized data for research. The final sample of this study included a total of 12,907 employees from 14 different companies. The organizations in the sample were from a variety of industries, including financial services, higher education, manufacturing, higher education, among others in the United States. There was a participation rate of 14% across organizations of employees who completed the Workplace Culture of Health Scale.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Workplace culture of health (COH)

The Workplace Culture of Health (COH) scale – Short Form is a 14-item assessment that measures employee perceptions of how their workplace supports their health and wellbeing with a 5-point rating scale [31, 32]. The short form of the workplace COH Scale has a strong internal reliability consistent with the full scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92). Domains measured in the scale include (1) senior leadership, policies, and practices, (2) supervisor support, (3) coworker support, and (4) employee morale. Senior leadership, policies, and practices assess an organization’s resources, policies, and procedures related to health and wellbeing. Supervisor support has questions related to the immediate supervisor attitudes to employee health and wellbeing. Coworker support assesses collective beliefs, norms, and behaviors from coworkers related to health and wellbeing. Employee morale addresses employee satisfaction, trust, and confidence with their employer. Participants rate the extent they agree or disagree with the statements provided, with responses ranging from strongly agree (5) to strongly disagree (1). Total and subdomain scores are calculated by dividing the total points by the total possible points.

2.2.2 Depression

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) is a 2-item scale used to measure participants’ self-reported frequency of depressed mood [29]. This measure was included on the employees’ HRA. The items ask participants to rate the degree to which an individual has experienced symptoms of depression over the past two weeks on a scale of not at all (0) to nearly every day (3). The items include “little interest or pleasure in doing things” and “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless.” Total scores were calculated by adding the two items. A score of 3 or above indicates a risk for depression and should undergo additional screening to see if they meet the criteria for depressive disorders. Participants are considered “not at risk” if their scores are between 0 and 3 and were considered “at risk” for scores 4–6. Prior studies have shown that is a valid and reliable measure for detecting depression [29].

2.2.3 Physical activity

Physical activity (PA) was measured through five questions about their time spent in moderate to vigorous PA, sedentary time, and the number of days engaged in strength training in the past seven days [35]. These questions were included on employees’ HRA and the questions were derived from the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) [27]. Participants were asked about the number of minutes spent in vigorous and moderate PA and to select the number of days per week they engaged in strength training activities. Participants were considered “not at risk” if they engaged in at least 150 min of moderate to vigorous PA and strength training at least two days per week while participants were considered “at risk” if they did not meet this guideline. This categorization is consistent with the IPAQ [27] and the American PA Guidelines [37]. The American PA Guidelines are widely recognized and endorsed as a scientifically sound standard for assessing appropriate PA levels, therefore was used into this study to assess PA risk [38].

2.2.4 Demographic data

Participants were asked to report their gender, age, and job class. For job class, participants could choose from either “individual contributor,” meaning no direct reports, or “supervisor,” meaning they manage employees. Data such as race, ethnicity, and tenure at organization were not available.

2.2.5 Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics was calculated for all variables for the total group, by gender, and by job class. Means and standard deviations was calculated for continuous variables (workplace COH and age) and counts and percentages was calculated for categorical variables (PA, depression, job class, and gender) to describe the distribution. In addition, the data was screened for missing data and outliers. Further, the data was checked for normality using skewness and kurtosis.

To examine if workplace COH was associated with PA, a multilevel logistic regression model was conducted. In this model, workplace COH was the primary predictor and PA engagement was the primary outcome variable. In addition, gender, depression risk, age and job class were included as predictors in the model. A logistic regression was used because the primary outcome variable, PA, was coded as a binary categorical variable (at risk or not at risk). A multilevel model was an appropriate technique for the data because employees were nested within their organization, therefore there may be some correlation between their scores. To assess if the data was suitable for a multilevel model, we investigated if there was variation between the contexts (in this case, organization). First, a baseline model was fit where only the intercept (workplace COH) was included. Then, we fit a model that allowed the workplace COH scores to vary over the organizations. We examined each model and determined that the second model was most appropriate as shown through a decrease in the AIC and BIC. In addition, an ANOVA confirmed a significant change in the likelihood ratio between the models, which indicates that the intercepts vary significantly across organization. This confirmed that the multilevel model was most appropriate [16].

To examine if gender and depression risk moderated the relationship between workplace COH and PA, an additional multilevel logistic regression model was run that included interaction terms for COH, gender and depression risk, with age and job class as a covariate. Multicollinearity was checked for each model using the variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance (T) scores. No multicollinearity was indicated with VIF scores below five (1.01–3.80) and all the T scores above 0.01 (0.02–0.99). The assumption of linearity was also checked by looking at the interaction term between the continuous predictor (workplace COH) and the logit of the outcome variable (PA engagement). Model fit was assessed using log-likelihood and interpreted using the value of odds ratios. All analysis was conducted in RStudio [39].

3 Results

Among 12,907 participants, approximately 65% of the participants were female, and the average age of the entire sample was 43 years (SD = 12). Detailed demographic information can be found in Table 1. Regarding PA, approximately 34% of the sample was considered “at risk” for physical activity (in other words, they did not meet the physical activity guidelines). Notably, this percentage is much lower than the typical rate observed in the U.S. adult population, where over 75% of individuals do not meet the physical activity guidelines (Center for Disease Control, n.d.). Additionally, 6% of the sample scored a 4 or higher on the PHQ-2, indicating they were “at risk” for depression. Once again, this prevalence is lower than the typical rate observed in U.S. adults, where approximately 17% have experienced depression [20]. On average, males scored their workplace culture of health at 74.38 out of 100, while females scored an average of 73.13 out of 100, which indicates employees of both genders feel they are moderately supported by the workplace with regards to health and wellbeing [30].

Table 2 presents the results of the effects of workplace COH, gender, and depression on PA engagement. Age and job class was included as a covariate in the model. The results of a multilevel logistic regression model indicated that workplace COH scores were a significant predictor of PA engagement, where an increase in COH score was associated with increased odds of PA engagement (OR = 1.058, p < 0.001). In addition, depression risk (OR = 1.57, p < 0.001) and gender (OR = 1.71, p < 0.001) were also significant predictors of PA engagement, where being male and being not at risk for depression were associated with greater odds of engaging in PA.

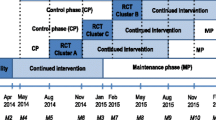

Table 2 also shows the results of model examining gender and depression risk as moderators of the relationship between workplace COH and PA engagement. Figure 1 displays a conceptual model to visualize the moderation analysis. The results of the multilevel logistic model with interaction terms showed that gender moderated the relationship between workplace COH scores and PA engagement (OR = 1.23, p = 0.001), where males observed a greater increased in the odds of engaging in PA as COH scores increased than females did. In addition, there was a significant interaction between COH scores, gender, and depression risk (OR = 0.80, p = 0.026). This interaction is demonstrated in Figs. 2, 3, which show the predicted probability of engaging in PA based on COH scores. The results indicated that for both males and females who were not at risk for depression, an increase in COH scores were associated with an increased probability of engaging in PA. Similarly, for males at risk for depression, an increase in COH scores were associated with an increased probability of engaging in PA. However, for females at risk for depression, an increased in COH scores were associated with a decreased probability in engaging in PA (Fig. 2).

4 Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between employee perceptions of the workplace culture of health (COH) and physical activity (PA) engagement. The study revealed that workplace COH was associated with PA engagement, but the relationship varied based on gender and depression risk. These findings shed light on the potential impact of the workplace environment on promoting healthy behaviors among employees.

As hypothesized, the results showed that workplace COH was a significant predictor of PA engagement, even when controlling for gender, depression risk, and age. This finding is consistent with a previous study on 1732 Taiwanese employees, which found that peer support for healthy behavior, a domain of workplace COH, was associated with increased employee PA [9]. In our study, males overall reported higher workplace COH scores, higher levels of PA engagement, and lower levels for depression compared to their female counterparts. This is in line with previous research examining gender differences in health outcomes such as physical activity and depression [21, 24]. Our study also revealed that gender moderated the relationship between workplace COH and PA engagement, where males had a greater increase in the odds of engaging in PA as their workplace COH scores increased than females did.

As expected, we found that depression risk also influenced the relationship between gender, workplace COH and PA engagement. Specifically, among employees who are at risk for depression, an increase in COH scores were associated with higher PA engagement for men but not for women. This unique finding illustrates the complexity and nuance among promoting health at work, suggesting that a supportive workplace culture may have a strong influence on PA engagement among men who are at risk for depression. On the other hand, our study also showed that among employees who are not at risk for depression, an increase in COH scores were associated with higher PA engagement for both males and females. This indicates that a health-supportive workplace culture can positively impact PA engagement for individuals without depression risk, regardless of gender.

These findings emphasize the importance of considering gender and mental health factors when designing workplace wellness initiatives. Organizations should recognize the varying needs and preferences of their employees to tailor interventions that effectively promote PA engagement. Strategies aimed at fostering a culture of health should address the specific barriers and facilitators to PA for different employee subgroups, considering gender and mental health considerations. The results also highlight the potential of the workplace as a key setting for promoting PA and improving population health. With adults spending a significant portion of their waking hours at work, the workplace offers a valuable opportunity to support and encourage healthy behaviors. By establishing a health-supportive culture, organizations can create an environment that motivates and facilitates PA engagement among employees. This, in turn, can contribute to reducing the risk of chronic diseases and enhancing overall well-being.

It is important to note that the findings of this study contribute to the growing body of research on workplace COH and PA engagement, where there are currently very few studies that have examined this relationship. However, there are limitations that should be acknowledged. The study relied on self-report measures, which may be subject to response biases and social desirability effects. There was also little information on employee tenure and industry, limiting the generalizability of these findings. Additionally, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality and examine long-term effects. Further, the low response rate to the survey raises the potential for selection effects, as participants may differ from non-respondents. It is possible that the data is skewed towards participants who are more interested in physical fitness, thereby indicating a low external representativity. Response bias may have influenced the reported levels of physical activity (PA) due to employees over-reporting positive behaviors they believe would be desirable to their employers. While it is possible bias was introduced since data collection occurred on a commercial platform, the assessment was based on evidence-based tools as described in the methods section. Finally, employees self-categorized into supervisory or non-supervisory employees, which may oversimplify roles or lack nuance in describing differences in positions. Future research should consider longitudinal designs and objective measures of PA to further explore the relationship between workplace COH and PA engagement.

In conclusion, the findings of this study underscore the significance of workplace COH in promoting PA engagement. Establishing a health-supportive workplace culture has the potential to enhance PA levels, thereby improving population health outcomes. However, the nuanced findings related to gender and depression risk emphasize the complexity of PA engagement and the need for tailored interventions. By recognizing and addressing these factors, organizations can create environments that foster a culture of health and facilitate healthy behaviors among their employees.

Data availability

The data are not publicly available but can be made available on reasonable request.

References

Alavinia SM, Molenaar D, Burdorf A. Productivity loss in the workforce: associations with health, work demands, and individual characteristics. Am J Ind Med. 2009;52(1):49–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.20648.

Asay GRB, Roy K, Lang JE, Payne RL, Howard DH. Absenteeism and employer costs associated with chronic diseases and health risk factors in the US workforce. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E141. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd13.150503.

Biddle S. Physical activity and mental health: evidence is growing. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(2):176–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20331.

Blair SN. Physical inactivity: the biggest public health problem of the 21st century. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(1):1–2.

Burton WN, Chen C-Y, Li X, Schultz AB, Abrahamsson H. The association of self-reported employee physical activity with metabolic syndrome, health care costs, absenteeism, and presenteeism. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(9):919–26.

Calderwood C, ten Brummelhuis LL, Patel AS, Watkins T, Gabriel AS, Rosen CC. Employee physical activity: a multidisciplinary integrative review. J Manag. 2021;47(1):144–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206320940413.

Carlson SA, Adams EK, Yang Z, Fulton JE. Percentage of deaths associated with inadequate physical activity in the United States. Prevent Chronic Dis. 2018. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd18.170354.

Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Pratt M, Yang Z, Adams EK. Inadequate physical activity and health care expenditures in the United States. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;57(4):315–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2014.08.002.

Chang Y-T, Tsai F-J, Yeh C-Y, Chen R-Y. From Cognition to Behavior: associations of workplace health culture and workplace health promotion performance with personal healthy lifestyles. Front Public Health. 2021;9: 745846. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.745846.

Chekroud SR, Gueorguieva R, Zheutlin AB, Paulus M, Krumholz HM, Krystal JH, Chekroud AM. Association between physical exercise and mental health in 1·2 million individuals in the USA between 2011 and 2015: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(9):739–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30227-X.

Claxton G, Rae M, Damico A, Young G, Kurani N, Whitmore H. Health Benefits In 2021: employer programs evolving in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: study examines employer-sponsored health benefits programs evolving in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Aff. 2021;40(12):1961–71.

Conn VS, Hafdahl AR, Mehr DR. Interventions to increase physical activity among healthy adults: meta-analysis of outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(4):751–8. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.194381.

Dinas PC, Koutedakis Y, Flouris AD. Effects of exercise and physical activity on depression. Ir J Med Sci. 2011;180(2):319–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-010-0633-9.

Edmunds S, Stephenson D, Clow A. The effects of a physical activity intervention on employees in small and medium enterprises: a mixed methods study. Work. 2013;46(1):39–49.

Elgaddal N, Kramarow EA, Reuben C. Physical activity among adults aged 18 and over: United States, 2020. NCHS Data Brief. 2022;443:1–8.

Field A, Miles J, Field Z. Discovering Statistics Using R. SAGE Publications. 2012

Flynn JP, Gascon G, Doyle S, Matson Koffman DM, Saringer C, Grossmeier J, Tivnan V, Terry P. Supporting a culture of health in the workplace: a review of evidence-based elements. Am J Health Promot. 2018;32(8):1755–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117118761887.

Goetzel RZ, Henke RM, Tabrizi M, Pelletier KR, Loeppke R, Ballard DW, Grossmeier J, Anderson DR, Yach D, Kelly RK, McCalister T, Serxner S, Selecky C, Shallenberger LG, Fries JF, Baase C, Isaac F, Crighton KA, Wald P, Metz RD. Do workplace health promotion (Wellness) programs work? J Occupat Environ Med. 2014;56(9):927–34.

Golden S, McLeroy KR, Green LW, Earp JAL, Lieberman LD. Upending the social ecological model to guide health promotion efforts toward policy and environmental change. Health Educat Behav. 2015;42(1_suppl):8–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198115575098.

Goodwin RD, Dierker LC, Wu M, Galea S, Hoven CW, Weinberger AH. Trends in U.S. depression prevalence from 2015 to 2020: the widening treatment gap. Am J Prevent Med. 2022;63(5):726–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2022.05.014.

Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, Guthold R, Haskell W, Ekelund U. Global physical activity levels: Surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. The Lancet. 2012;380(9838):247–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60646-1.

Henke RM, Head MA, Kent KB, Goetzel RZ, Roemer EC, McCleary K. Improvements in an organization’s culture of health reduces workers’ health risk profile and health care utilization. J Occup Environ Med. 2019;61(2):96–101. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000001479.

Johnston DA, Harvey SB, Glozier N, Calvo RA, Christensen H, Deady M. The relationship between depression symptoms, absenteeism and presenteeism. J Affect Disord. 2019;256:536–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.06.041.

Kessler RC, Walters EE, Forthofer MS. The social consequences of psychiatric disorders, III: probability of marital stability. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(8):1092–6. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.155.8.1092.

Kuehner C. Why is depression more common among women than among men? The Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(2):146–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30263-2.

Lee I, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. The Lancet. 2012;380(9838):219–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9.

Lee P, Macfarlane DJ, Lam TH, Stewart SM. Validity of the international physical activity questionnaire short form (IPAQ-SF): a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutrit Phys Activity. 2011;8:115. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-8-115.

Liu Y, Ozodiegwu ID, Yu Y, Hess R, Bie R. An association of health behaviors with depression and metabolic risks: data from 2007 to 2014 U.S. National health and nutrition examination survey. J Affect Disord. 2017;217:190–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.04.009.

Löwe B, Kroenke K, Gräfe K. Detecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnaire (PHQ-2). J Psychosom Res. 2005;58(2):163–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.09.006.

Marenus MW, Marzec M, Chen W. Association of workplace culture of health and employee emotional Wellbeing. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912318.

Marenus MW, Marzec M, Chen W. A scoping review of workplace culture of health measures. Am J Health Promot. 2023;37:08901171231179160.

Marenus MW, Marzec M, Kilbourne A, Colabianchi N, Chen W. The validity and reliability of the workplace culture of health scale—short form. J Occup Environ Med. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000002949.

Mattke S, Kapinos K, Caloyeras JP, Taylor EA, Batorsky B, Liu H, Van Busum KR, Newberry S. Workplace Wellness Programs programs: services offered, participation, and incentives. Rand Health Quarterly. 2015;5(2):7.

Mielke GI, da Silva ICM, Kolbe-Alexander TL, Brown WJ. Shifting the physical inactivity curve worldwide by closing the gender gap. Sports Med. 2018;48(2):481–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0754-7.

Mills PR, Masloski WS, Bashaw CM, Butler JR, Hillstrom ME, Zimmerman EM. Design, development and validation of the RedBrick Health Assessment: a questionnaire-based study. JRSM Short Reports. 2011;2(9):71. https://doi.org/10.1258/shorts.2011.011015.

O’Neill Hayes T, Gillian S. Chronic disease in the United States: a worsening health and economic crisis. American Action Forum. 2020.

Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, George SM, Olson RD. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320(19):2020–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.14854.

Powell KE, King AC, Buchner DM, Campbell WW, DiPietro L, Erickson KI, Hillman CH, Jakicic JM, Janz KF, Katzmarzyk PT, Kraus WE, Whitt-Glover MC. The scientific foundation for the physical activity guidelines for Americans. J Phys Activ Health. 2018;16(1):1–11.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Computer software]. 2022. https://www.R-project.org/.

Schuch F, Vancampfort D, Firth J, Rosenbaum S, Ward P, Reichert T, Bagatini NC, Bgeginski R, Stubbs B. Physical activity and sedentary behavior in people with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2017;210:139–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.050.

Schwartz MA, Aytur SA, Evenson KR, Rodríguez DA. Are perceptions about worksite neighborhoods and policies associated with walking? Am J Health Promot. 2009;24(2):146–51. https://doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.071217134.

Slentz CA, Houmard JA, Kraus WE. Modest exercise prevents the progressive disease associated with physical inactivity. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2007;35(1):18. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.jes.0000240019.07502.01.

Zhang J, Yen ST. Physical activity, gender difference, and depressive symptoms. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(5):1550–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12285.

Zhang Z, Chen W. A systematic review of the relationship between physical activity and happiness. J Happiness Stud. 2019;20(4):1305–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-9976-0.

Zhang Z, Chen W. Longitudinal associations between physical activity and purpose in life among older adults: a cross-lagged panel analysis. J Aging Health. 2021;33(10):941–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/08982643211019508.

Acknowledgements

We’d like to thank Elliott Metzler for his contributions to the analysis and interpretation of this data.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.W.M and M.M., conceived and designed the study. M.M. conducted the data collection. M.W.M. managed the data, methodology, and analysis. W.C. provided critical guidance throughout the research process. M.W.M. drafted the manuscript, and W.C., M.M., A.K., and N.C. provided significant revisions and edits. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because the research involved a de-identified dataset that cannot be reidentified by any known entity (HUM00221502). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Consent to publish was also obtained.

Consent to publication

Not applicable. No identifying information is reported. Participants were informed in the consent form that de-identified aggregate data would be used for publication.

Competing interests

AK, NC, and WC report no conflicts of interest. MWM and MWM are employees of Virgin Pulse, who license the survey tool from the University of Michigan. Virgin Pulse had no role in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication. There are no additional financial disclosures to report.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Marenus, M.W., Marzec, M., Kilbourne, A. et al. Workplace culture of health and employee physical activity: the moderating effects of gender and depression. Discov Psychol 4, 70 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-024-00173-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-024-00173-y