Abstract

Background

The International Physical Activity Questionnaire - Short Form (IPAQ-SF) has been recommended as a cost-effective method to assess physical activity. Several studies validating the IPAQ-SF have been conducted with differing results, but no systematic review of these studies has been reported.

Methods

The keywords "IPAQ", "validation", and "validity" were searched in PubMed and Scopus. Studies published in English that validated the IPAQ-SF against an objective physical activity measuring device, doubly labeled water, or an objective fitness measure were included.

Results

Twenty-three validation studies were included in this review. There was a great deal of variability in the methods used across studies, but the results were largely similar. Correlations between the total physical activity level measured by the IPAQ-SF and objective standards ranged from 0.09 to 0.39; none reached the minimal acceptable standard in the literature (0.50 for objective activity measuring devices, 0.40 for fitness measures). Correlations between sections of the IPAQ-SF for vigorous activity or moderate activity level/walking and an objective standard showed even greater variability (-0.18 to 0.76), yet several reached the minimal acceptable standard. Only six studies provided comparisons between physical activity levels derived from the IPAQ-SF and those obtained from objective criterion. In most studies the IPAQ-SF overestimated physical activity level by 36 to 173 percent; one study underestimated by 28 percent.

Conclusions

The correlation between the IPAQ-SF and objective measures of activity or fitness in the large majority of studies was lower than the acceptable standard. Furthermore, the IPAQ-SF typically overestimated physical activity as measured by objective criterion by an average of 84 percent. Hence, the evidence to support the use of the IPAQ-SF as an indicator of relative or absolute physical activity is weak.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With changing social and economic patterns all over the world, sedentary lifestyles have become a worldwide phenomenon [1, 2]. Sedentary lifestyles are associated with increased obesity, type 2 diabetes [3], and cardiovascular disease [4], and hence the promotion of active lifestyles is an important public health priority. To monitor trends and evaluate public health or individual interventions aiming at increasing levels of physical activity, reliable and valid measures of habitual physical activity are essential. Several routine instruments are available to measure physical activity, including self-report questionnaires, indirect calorimetry, direct observation, heart rate telemetry, and movement sensors [5]. All of these methods have well-known limitations [6], and for physical activity there is currently no perfect gold-standard criterion [7, 8]. Movement sensors such as accelerometers have grown in popularity recently as a measure of physical activity [9], not only due to their objective measurements, but also due to their relatively small and unobtrusive size. Nevertheless, due to their high costs, accelerometers are not usually practical in large-scale cohort studies and instead questionnaires are frequently used to obtain physical activity data [10, 11].

There are numerous available choices for questionnaires measuring physical activity [12]. Recent reviews have documented 85 self-administered physical activity questionnaires for adults [13], 61 for youth [14], and 13 for the elderly [15]. Many of these questionnaires have study-specific items and time referents, severely limiting the potential for comparisons across different studies. For example, the Synchronized Nutrition and Activity Program [16] measures activity relevant only to primary school children, and contains items that are not common across broad sectors of the population. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) was developed to address these concerns by a group of experts in 1998 to facilitate surveillance of physical activity based on a global standard [17]. The IPAQ has since become the most widely used physical activity questionnaire [13], with two versions available: the 31 item long form (IPAQ-LF) and the 9 item short form (IPAQ-SF). The short form records the activity of four intensity levels: 1) vigorous-intensity activity such as aerobics, 2) moderate-intensity activity such as leisure cycling, 3) walking, and 4) sitting. The original authors recommended the "last 7 day recall" version of the IPAQ-SF for physical activity surveillance studies [17], in part because the burden on participants to report their activity is small.

A common analysis method used to demonstrate questionnaire validity is to correlate self-reported activity data from the IPAQ-SF with data from an objective measurement device(s), both of which are obtained over exactly the same time period (concurrent validity). Another common method is to compute the absolute differences between the objective and self-reported measure. Both methods are essential in determining the validity of the IPAQ-SF, and a systematic review of the analyses that have been used to validate the IPAQ-SF would therefore be useful in assessing the merits of using the IPAQ-SF in epidemiological studies.

The first comprehensive validation of the IPAQ-SF was conducted across 12 countries, and reported correlations (all correlations reported were Spearman ρ's for the last 7 day's report) with the uniaxial CSA model-7164 accelerometer. A wide range of Spearman correlations, ρ = 0.02 (Sweden) - 0.47 (Finland), raised concerns of variability in validity in different populations. Variability in reported validity may be caused by several factors such as the demographic and cultural backgrounds of the participants, the way the information requested is processed and delivered, as well as variations in the "criterion gold-standard" used for objective comparison. Criterion measures used for IPAQ-SF validation have included the actometer [18], accelerometer [19] and pedometer [20], yet only one study has used the expensive doubly labeled water technique [21] as a criterion even though it has been recommended and is considered the most accurate objective measurement of physical activity [8, 22]. In addition to traditional measures of physical activity, various fitness measures (e.g. maximum oxygen uptake, VO2max [23]) have also been used as a reference standard to compare the IPAQ-SF because physical activity is strongly associated with cardiorespiratory fitness [24]. Several of the objective measures yield different indices of activity, and the findings regarding validity may vary according to which index and objective measure is used as the standard, for example, both time spent in physical activity and raw count data have been used as a measure of physical activity from accelerometer [25]. Variations also occur in how the objective measured data were transformed, for example the transformation algorithm from raw accelerometer data to time spent in moderate to vigorous physical activity [26, 27]. There have also been inconsistencies in the reporting of "total physical activity" from IPAQ-SF data, with studies using units involving metabolic equivalent task (MET), time spent in activity, or simply a trichotomized variable indicating the adequacy of physical activity [28]. The IPAQ-SF instrument may also be better at capturing activity of some intensity level but not others, e.g., vigorous rather than moderate activity. Because the variability shown in the IPAQ-SF validity from these international studies has not been collated and systematically examined, we reviewed the effect of these sources on IPAQ-SF validity.

The IPAQ was first published with its validation based on a 12-country sample, and the authors recommended using the short form which measured physical activity by self-report over the previous 7 days [17]. Since that time, more validation studies have been published for this short-form than for any other physical activity questionnaires [13]. Despite the popularity of the IPAQ-SF and its widely accepted high reliability [13, 17], there has been no systematic review of its validity. Van Poppel et al. [13] have published a review of physical activity questionnaires used in adults, but included only four studies of the IPAQ-SF. Hence, a more comprehensive review of the IPAQ-SF is needed using data from the English language literature, with a focus on the variability of its relationship with the various validation measures as well as its absolute accuracy.

This paper has two objectives: (1) to review the analyses used in the IPAQ-SF validation studies, and (2) to consider possible explanations for differences between studies. For the first objective, we reviewed the studies validating the IPAQ-SF as a relative measure (i.e. studies that show a correlation with objective measures of physical activity) and/or an absolute measure (i.e. studies that compare levels of physical activity obtained by the IPAQ-SF against levels from an objective measure) of physical activity level. For the second objective, we examined whether the demographics of different samples, the indices derived from objective standards or the IPAQ-SF, or additional moderators which had contributied to the different levels of validity reported. Since the IPAQ-SF has been consistently shown to have a high reliability (ranging from 0.66 to 0.88) [17, 20, 25], we will not study this property here. We examined studies that sought to validate both (a) the overall physical activity score from the IPAQ-SF, as well as (b) those that focused on restricted information from the scale, e.g., different levels of intensity (vigorous activity, moderate activity and walking).

Methods

Literature search

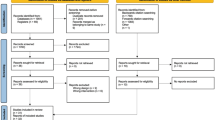

We searched in PubMed and Scopus for papers examining the validity of the IPAQ-SF through November 2010, using the keywords "IPAQ AND (validity OR validation)". Additional papers were gathered by searching the reference lists from the searched papers.

Inclusion criteria

Each paper had to satisfy the following criteria in order to be included in our review. First, the validation had to be of the short form against an objective physical activity measuring device, (e.g., accelerometer or pedometer), or an objective fitness/anthropometric measure (e.g. VO2max or % body fat). Validation papers of the IPAQ-SF against self-reported measures such as other physical activity questionnaires or log-books, and reliability studies without validity information were not included. Second, the article was published in English.

Search result

The search in PubMed and Scopus yielded 51 and 56 papers respectively (with a total of 59 unique papers). Of these, 38 papers were excluded for the following reasons: 13 papers used the IPAQ long form; 11 papers validated other measures using the IPAQ-SF as the standard; five papers were not in English; three papers validated a modified version of the IPAQ-SF; three papers were applications of the IPAQ-SF; one paper reviewed properties of physical activity questionnaires among the elderly; one was a comment article and one was a qualitative study translating the IPAQ-SF. Two more papers were identified through the reference lists of the papers reviewed [28, 29]. Overall, 23 studies were reviewed in the present paper [17–20, 23, 25, 28–44] and their general characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Data extraction

The following information was extracted from papers included in the review: (1) validity data, i.e. a) the correlation between different levels of intensity of the IPAQ-SF (vigorous activity, moderate activity, walking) and their corresponding time spent measured by the objective standard; and b) whether raw values were reported and if so, the percentage difference between the IPAQ-SF and the objective standard (with the objective standard used as the reference). (2) In addition, the following potential sources of variability in findings were noted: a) the country of study, the target population (if specified), and the size and demographics of the sample; b) the objective physical activity measure(s) and/or the fitness measure(s) used as the objective standard; c) the unit of measurement of the objective standard (for example, raw accelerometer counts, metabolic equivalent task (MET), total time spent on physical activity, MET-transformed energy expenditure, etc.), and the cutoff levels used to categorize activity into moderate and vigorous activity; d) the correlation between the IPAQ-SF total activity level (MET, time spent, or any novel definition introduced by the investigators) and the objective standard; and e) potential factors influencing the relationships reported between the IPAQ-SF and the objective physical activity or fitness measures.

Data synthesis and analysis

Results of the 23 studies were synthesized into four categories: (1) validity of the IPAQ-SF to measure overall physical activity; (2) validity of the IPAQ-SF to measure specific levels of physical activity; (3) accuracy of IPAQ-SF; and (4): factors that might relate to the variability of IPAQ-SF validity.

Table 2 presents information from 16 studies [17–20, 23, 25, 29–37, 39] regarding the standard, unit, and activity value used, and the correlation of the objective standard with the IPAQ-SF and its associated effect size in the different studies examining physical activity on a continuum. Table 3 presents the remaining 7 studies which did not present information from continuous measures of physical activity [28, 41], did not present information for the whole sample but in subgroups [40, 43], and presented only correlations for specific intensity [38, 42, 44]. Most studies examined the validity of the IPAQ-SF by reporting the Spearman ρ for the relationship between the scale and the objective physical activity measure(s) and/or the fitness measure(s). Using Ferguson's [45] guideline for effect size interpretation for the ρ, values of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 were described as small, moderate, and large effects respectively. Effect sizes below 0.2 are reported in this paper as negligible. Using Terwee and colleagues' guidelines [8], effect sizes above 0.5 were considered acceptable for correlations against objective activity measuring devices, and above 0.4 for fitness measures. Table 3 presents the studies that examined the validity of the IPAQ-SF by examining the correlation between the scale and the physical activity/fitness measures at different levels of intensity. This table includes information from 15 studies [20, 23, 25, 28, 30, 34–38, 40–44], 8 of which [20, 23, 25, 30, 34–37] presented overlapping data from continuous measures of physical activity are also included in Table 2. For studies that examined the validity of IPAQ-SF at specific levels of intensity, the correlation between the IPAQ-SF and the objective physical activity measures are shown in Table 3. Table 4 presents under- and over-reporting of physical activity by the IPAQ-SF compared to objective data from the accelerometer. Six studies provided information relevant to this aim.

Results

Validity of the overall IPAQ-SF: overall physical activity level

These data are presented in Table 2. The IPAQ-SF showed negligible to small correlations in total activity level with objective measuring devices (range of ρ = 0.09 [19] to 0.39 [36], median = 0.29). Among the 18 correlations reported for objective measuring devices [17 - 20, 23, three reported in 25, 29, 30, two reported in 31, 32 - 35, 39], 16 of them were regarded as small and the others were negligible. In general, the correlation of the IPAQ-SF with accelerometer data (range of ρ = 0.09 [19] to 0.39 [36], median = 0.28) was the same with that of the pedometer (range of ρ = 0.25 [25] to 0.33 [20], median = 0.28) and actometer (ρ = 0.33 [18]).

With fitness measures (VO2max, maximum treadmill time, and 6-minute walk test reported in the lower section of Table 2), the correlations with the IPAQ-SF total activity level were small in four of the five studies (range of ρ = 0.16 [33] to 0.36 [37], median = 0.30). Only one study validated the IPAQ-SF against anthropometric measures, which reported a small correlation between the IPAQ-SF and body fat percentage (ρ = -0.19 [44], not shown in any tables).

In the only study using doubly labeled water as the criterion measure [28], the validity of the IPAQ-SF was assessed by categorizing participants into insufficiently active, sufficiently active, and highly active based on their IPAQ-SF scores (Table 3). The total energy expenditure (TEE) and physical activity level (PAL) (both measured using doubly labeled water) were then compared across the three categories. TEE and PAL in the highly active participants were significantly higher than that of the other two groups, and the authors concluded that highly active participants could be correctly identified, and distinguished from inactive participants using the IPAQ-SF, but other discrimination was poor [28].

Validity of the IPAQ-SF: specific levels of intensity

These data are presented in Table 3. Three studies [20, 38, 43] reported moderate to large correlations (ρ ≥0.5) for one of the different levels of intensity (vigorous activity, moderate activity, and walking) (superscript a in column 4-6 of Table 3). Of the four correlations [20, 38, two reported in 43] in the moderate range or higher (ρ ≥ 0.5), three [20, two reported in 43] were correlations related to walking time and the remaining one [38] related to moderate activity. All the above four correlated IPAQ-SF against accelerometer or pedometer values [20, 38, two reported in 43]. In addition, two studies [36, 43] reported values in the 0.40 to 0.49 range for time spent on walking and accelerometer count. Time spent on walking seemed to correlate best with accelerometer/pedometer counts.

Of the five remaining studies [25, 34, 36, 37, 43] (superscript b in column 4-6 of Table 3) reporting correlations approaching the moderate level (ρ = 0.40 - 0.49), all measured activity at the vigorous level; two were correlations between vigorous activity time and fitness measures (VO2max [34] and maximum treadmill time [37]), and the other three were for vigorous time spent measured against accelerometer data [25, 36, 43]. As the correlation for validation against fitness measures is recommended as ρ = 0.40, there was some support for the validity of the IPAQ-SF in measuring vigorous activity. However, it should be noted that these represent only a third of the correlations reported against the fitness measures.

Accuracy of the IPAQ-SF

Table 4 shows the accuracy of the IPAQ-SF. Six studies provided the amount in physical activity measured by the IPAQ-SF and objective data [19, 25, 31, 35, 36, 42], but surprisingly, none of them computed the percentage of over- or under-reporting of physical activity, or used the absolute difference as an indicator of validity. Furthermore, standard deviations were not provided by these studies, making it impossible to compute the effect size for the differences between the IPAQ-SF and the objective device. Under-reporting of physical activity (-28%) was present in only one study [31], but in the other five studies [19, 25, 35, 36, 42], over-reporting by the IPAQ-SF of 106 percent on average when compared to the accelerometer was found (range 36 - 173%).

Factors that might relate to variability of validity findings

Demographics

None of the demographic characteristics, including place of study, targeted population, sample size, male-female ratio, and age, seemed to be related to differences in validity between the IPAQ-SF and the criterion measure (Tables 1 and 2).

Objective standard used for validation

Fifteen studies used an objective device that monitored body motion [17–20, 25, 29–32, 35, 38–40, 42, 43], two examined scores against a physical fitness measure [37, 41], four used both an objective device and a physical fitness measure [23, 33, 34, 36] and one compared findings against anthropometric measures [44] (Tables 2 and 3). Of those reporting data from motion-sensing devices, one of them used the actometer, two used a pedometer, and fifteen used an accelerometer. Two of them used both a pedometer and an accelerometer. Notably, only one study used doubly labeled water [28] (Table 3), the recommended criterion for validation [8, 22] to assess the validity of the IPAQ-SF.

Indices from objective standards used for validation

The third columns of Tables 2 and 3 indicate the unit used in the analyses. For the accelerometer device (excluding pedometers), and for the fitness measures, several different units were used and were not consistent across studies. Of the seventeen studies using an accelerometer as the objective standard (8 in Table 2 [18–20, 29, 31–33, 39], 4 in Table 3 [38, 40, 42, 43], and 5 in both [23, 25, 34–36]), four types of units were commonly reported (with some studies reporting multiple different units). These included (i) raw accelerometry counts without transformation (Counts [17, 25, 29, 31, 33, 35, 36, 40, 43]), (ii) count data to energy expenditure (TEE/AEE/PAL [23, 34, 39]), (iii) MET scores (MET min/wk [19, 25, 31, 32, 36, 38, 40, 42]), and (iv) time spent (Total PA min/wk [25, 31, 36, 38–40, 42, 43]). In addition to the variability of units used for reporting accelerometer data, there was also a great variability in the cutoffs used to transform the accelerometer data into MET min/wk. Three different cutoffs (Freedson [26], Swartz [27], and Trost [46]) were used among the aforementioned validation studies, yet overall, no pattern of difference in correlations was evident based on the use of the different cutoffs.

Nevertheless, this was not the case for the absolute discrepancy between the IPAQ-SF and the accelerometer scores (reported in Table 4). The only study using the Swartz cutoffs ([27], moderate PA: 574≤ count/min≤4945, vigorous PA: count/min > 4945) yielded an over-report of 36%, which appears relatively small compared with the average of 95% for the four studies [19, 25, 31, 42] using the Freedson cutoffs (moderate PA: 1952≤ count/min≤5724, vigorous PA: count/min > 5724) (Table 4). In theory, the Swartz cutoffs will yield a lower MET score than the Freedson cutoffs, because some of the time spent on moderate activity classified by the Swartz cutoffs (574≤ count/min < 1952) may be classified as inactive by the Freedson cutoffs, so that total time spent computed using the Swartz cutoffs will be higher than that using the Freedson cutoffs. Note that it is impossible to conclude that the Swartz's cutoffs are more appropriate simply because they reduce the over-report of the IPAQ-SF, as the true level of physical activity is not known. As the Trost's cutoffs depend on the age of the participants, no direct comparison to the other two cutoffs can be made. It is of interest that no published study has yet compared IPAQ-SF with the more recent weighted-accelerometer cutoffs suggested by Metzger et al [47].

Indices from the IPAQ-SF

Values obtained from the IPAQ-SF have also been used in different ways in the various studies. Of the sixteen studies that computed the total physical activity from the IPAQ-SF (Table 2), six [25, 29, 30, 32, 33, 37] used total time spent (Total PA min/wk), nine [17–20, 31, 34–36, 39] transformed the total time spent to MET scores (MET min/wk), and one [23] used a novel trichotomized variable indicating the adequacy of physical activity (3 categories). Again, no pattern across the correlations was evident based on the use of these different indices.

Other potential moderators

Two studies aimed at finding potential factors influencing the validity of the IPAQ-SF. One group studied the relationship between the participant's confidence in accurately recalling physical activity on the IPAQ-SF [40], whilst the second group examined whether keeping physical activity logbooks improved the validity of the IPAQ-SF report [42]. The resultant correlations ranged from 0.15 to 0.30, whilst the confidence ratings and the act of completing daily logbooks did not influence the relationship between the IPAQ-SF and the objective measures. Although logbooks did not improve IPAQ-SF validity, one IPAQ-SF validation paper written in Chinese [48] showed that using a logbook to impute missing accelerometer data could yield an acceptable IPAQ-SF validity (Pearson correlation = 0.63, not shown in tables).

Discussion

A recently published checklist of attributes of physical activity questionnaires [8] suggested that correlations of 0.5 for moderate and vigorous activity and 0.4 for total energy expenditure or fitness should be the standard for an acceptable self-reported physical activity questionnaire. Despite the very broad range of methods reported in Table 2, the findings were quite consistent: the correlation between the IPAQ-SF overall scale and any index never reached the standard of 0.50 [13]. When the self-reported data from the IPAQ-SF was restricted to a narrower ranges of activity levels (Table 3), there were nominally more promising results. The total time spent derived from the IPAQ-SF for walking showed small-to-moderate correlations with step counts obtained from objective devices, with about one third of the correlations falling into the acceptable range. This was not the case for moderate or vigorous activity, which correlated weakly with measures from objective devices, yet time spent on vigorous activity correlated moderately well with fitness measures, with most of these correlations reaching an acceptable level. In summary, only four (with superscript a) of 74 correlations reported (Tables 2 and 3) were in the recommended range of > 0.50 for a correlation with an objective device, and two (with superscript b) of 12 correlations reported (Tables 2 and 3) were in the recommended range of > 0.40 for a correlation with a fitness measure.

For walking activity, most studies validated the results against the accelerometer, although one correlated moderate activity against the pedometer, as moderate walking is often associated with a MET = 3.3 [49], which is considered by some to be within the moderate intensity range of 3-5.9 METs [26]. When examining absolute accuracy, few studies reported absolute scores, and none reported standard deviations so the effect size of the difference in findings between the objective measure and the IPAQ-SF could not be computed. The smallest discrepancy reported was an under-estimate by the IPAQ-SF of 28 percent, yet most of these studies reported an over-estimate by the IPAQ-SF and showed considerable variability and the overall mean over-estimate in these studies was 106 percent. Over-reporting of physical activity by the IPAQ-SF is not uncommon [50], and it remains a key limitation of most self-reported measures of physical activity [51].

Future research directions

Only one study has validated the IPAQ-SF against doubly labeled water and despite the high cost, this criterion remains the recommended standard for studies comparing energy expenditure. Very few studies have evaluated the accuracy of the IPAQ-SF, i.e. the concordance of absolute values between the measure obtained by an objective physical device and that by the IPAQ-SF. It is recommended that further validation studies are needed using both research techniques.

The literature shows much variability in the reported units of activity used to compare against the IPAQ-SF data. For example, raw counts, MET scores, and time spent were used by researchers to report total activity levels derived from the accelerometer, with no consistency or apparent agreement. Greater consistency in the reporting of the accelerometry data would enhance future comparative studies. Furthermore, a variety of accelerometer cut-offs were used by different researchers to define categories of activity which alone would generate varying and incomparable results [52, 53]. These accelerometer cut-offs were determined by calibrating accelerometer counts during specific activities (e.g. housework, recreation), and all were typically calibrated in samples from the United States [26, 27, 46]. If the cutoffs are to be truly adopted globally with accelerometry research, similar and standardized studies are needed from different cultures.

Conclusions

Although the IPAQ-SF is recommended and widely used, our systematic review has found that in the large majority of validation studies only a small correlation with objective measures of activity was achieved. Nevertheless, there are a few exceptions, with vigorous activity and walking showing some acceptable correlations. Furthermore, the IPAQ-SF tends to overestimate the amount of physical activity reported compared to an objective device. As a result, the current evidence is fairly weak to support the use of the IPAQ-SF as either a relative, or as an accurate and absolute measure of physical activity, although its proven reliability shows it can be used with care in repeated measures studies, although the true magnitude of the change over time, if any, may not be accurate. Comparability of studies that wish to assess the validity of self-report questionnaires is achieveable if researchers use more consistent units and standardized categorization of intensity levels from accelerometry studies. Also, providing a distinction between validation strategies for relative and absolute interpretations of physical activity questionnaires is important.

References

Boon RM, Hamlin MJ, Steel GD, Ross JJ: Validation of the New Zealand physical activity questionnaire (NZPAQ-LF) and the international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ-LF) with accelerometry. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2010, 44: 741-746. 10.1136/bjsm.2008.052167.

Knuth AG, Bacchieri G, Victora CG, Hallal PC: Changes in physical activity among Brazilian adults over a 5-year period. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2010, 64: 591-595. 10.1136/jech.2009.088526.

Hu FB, Li TY, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Manson JE: Television watching and other sedentary behaviors in relation to risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. Journal of American Medical Association. 2003, 289: 1785-1791. 10.1001/jama.289.14.1785.

Warren TY, Barry V, Hooker SP, Sui X, Church TS, Blair SN: Sedentary behaviors increase risk of cardiovascular disease mortality in men. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2010, 42: 879-885. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c3aa7e.

Montoye HJ, Kemper HCG, Saris WHM, Washburn RA: Measuring Physical Activity and Energy Expenditure. 1996, Champaign: Human Kinetics

Welk GJ: Physical Activity Assessments for Health-Related Research. 2002, Champaign: Human Kinetics

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: The Surgeon General's Call to Action to Prevent and Decrease Overweight and Obesity. 2001, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Services, Office of the Surgeon General

Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, van Poppel MNM, Chinapaw MJM, van Mechelen W, de Vet HCW: Qualitative attributes and measurement properties of physical activity questionnaires: A checklist. Sports Medicine. 2010, 40: 525-537. 10.2165/11531370-000000000-00000.

Freedson PS, Miller K: Objective monitoring of physical activity using motion sensors and heart rate. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 2000, 71: S21-S30.

Jiang CQ, Thomas GN, Lam TH, Schooling CM, Zhang W, Lao XQ, Adab P, Leung GM, Cheng KK: Cohort profile: The Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study, a Guangzhou-Hong Kong-Brimingham collaboration. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2006, 35: 844-852. 10.1093/ije/dyl131.

Hallal PC, Victora CG, Wells JCK, Lima RC: Physical inactivity: Prevalence and associated variables in Brazilian adults. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2003, 35: 1894-1900. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000093615.33774.0E.

Pereira MA, FitzerGerald SJ, Gregg EW, Joswiak ML, Ryan WJ, Suminski RR, Utter AC, Zmuda JM: A collection of Physical Activity Questionnaires for health-related research. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1997, 29: S1-205.

van Poppel MNM, Chinapaw MJM, Mokkink LB, van Mechelen W, Terwee CB: Physical activity questionnaires for adults: A systematic review of measurement properties. Sports Medicine. 2010, 40: 565-600. 10.2165/11531930-000000000-00000.

Chinapaw MJM, Mokkink LB, van Poppel MNM, van Mechelen W, Terwee CB: Physical activity questionnaires for youth: A systematic review of measurement properties. Sports Medicine. 2010, 40: 539-563. 10.2165/11530770-000000000-00000.

Forsen L, Loland NW, Vuillemin A, Chinapaw MJM, van Poppel MNM, Mokkink LB, van Mechelen W, Terwee CB: Self-administrated physical activity questionnaires for the elderly: A systematic review of measurement properties. Sports Medicine. 2010, 40: 601-623. 10.2165/11531350-000000000-00000.

Moore HJ, Ells LJ, McLure SA, Crooks S, Cumbor D, Summerbell CD, Batterham AM: The development and evaluation of a novel computer program to assess previous-day dietary and physical activity behaviours in school children: The Synchronised Nutrition and Activity Program (SNAP). British Journal of Nutrition. 2008, 99: 1266-1274.

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman A, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, Pratt M, Ekelund U, Yngve A, Sallis JF, Oja P: International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2003, 35: 1381-1395. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB.

Scheeres K, Knoop H, van der Meer J, Bleijenberg G: Clinical assessment of the physical activity pattern of chronic fatigue syndrome patients: A validation of three methods. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2009, 7: 29-10.1186/1477-7525-7-29.

Macfarlane DJ, Lee CCY, Ho EYK, Chan KL, Chan DTS: Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of IPAQ (short, last 7 days). Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2007, 10: 45-51.

Deng HB, Macfarlane DJ, Thomas GN, Lao XQ, Jiang CQ, Cheng KK, Lam TH: Realiability and validity of the IPAQ-Chinese: The Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2008, 40: 303-307. 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815b0db5.

Lifson N, Gorden GB, McClintock R: Measurement of total carbon dioxide production by mean of D218O. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1955, 7: 704-710.

Plasqui G, Westerterp KR: Physical activity assessment with accelerometers: An evaluation against double labeled water. Obesity. 2007, 15: 2371-2379. 10.1038/oby.2007.281.

Rangul V, Holmen TL, Kurtze N, Cuypers K, Midthjell K: Reliability and validity of two frequently used self-administered physical activity questionnaires in adolescents. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2008, 8: 47-10.1186/1471-2288-8-47.

American College of Sports Medicine: Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 2006, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 7

Dinger MK, Behrens TK, Han JL: Validity and reliability of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire in college students. American Journal of Health Education. 2006, 37: 337-343.

Freedson P, Melanson E, Sirard J: Calibration of the computer science and applications, inc. accelerometer. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1998, 30: 777-781. 10.1097/00005768-199805000-00021.

Swartz AM, Strath SJ, Bassett DR, O'Brien WL, King GA, Ainsworth BE: Estimation of energy expenditure using CSA accelerometers at hip and wrist sites. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2000, 32: S450-S456. 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00003.

Ishikawa-Takata K, Tabata I, Sasaki S, Rafamantananatsoa HH, Okazaki H, Okibo H, Tanaka S, Yamamoto S, Shirota T, Uchida K, Murata M: Physical activity level in healthy free-living Japanese estimated by doubly labelled water method and International Physical Activity Questionnaire. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008, 62: 885-891. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602805.

Vandelanotte C, De Bourdeaudhuij IM, Philippaerts RM, Sjostrom M, Sallis JF: Reliability and validity of a computerized and Dutch version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2005, 2: 63-75.

De Cocker KA, De Bourdeaudhuij IM, Cardon GM: What do pedometer counts represent? A comparison between pedometer data and data from four different questionnaires. Public Health Nutrition. 2008, 12: 74-81.

Ekelund U, Sepp H, Brage S, Becker W, Jakes R, Hennings M, Wareham NJ: Criterion-related validity of the last 7-day, short form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire in Swedish adults. Public Health Nutrition. 2006, 9: 258-265.

Faulkner G, Cohn T, Remington G: Validation of a physical activity assessment tool for individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2006, 82: 225-231. 10.1016/j.schres.2005.10.020.

Kaleth AS, Ang DC, Chakr R, Tong Y: Validity and reliability of community health activities model program for seniors and short-form international physical activity questionnaire as physical activity assessment tools in patients with fibromyalgia. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2010, 32: 353-359. 10.3109/09638280903166352.

Kurtze N, Rangul V, Hustvedt B: Reliability and validity of the international physical activity questionnaire in the Nord-Trondelag health study (HUNT) population of men. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2008, 8: 63-10.1186/1471-2288-8-63.

Lachat CK, Verstraeten R, Le Nguyen BK, Hagstromer M, Nguyen CK, Nguyen DAV, Nguyen QD, Kolsteren PW: Validity of two physical activity questionnaires (IPAQ and PAQA) for Vietnamese adolescents in rural and urban areas. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2008, 5: 37-10.1186/1479-5868-5-37.

Mader U, Martin BW, Schutz Y, Marti B: Validity of four short physical activity questionnaires in middle-aged persons. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2006, 38: 1255-1266. 10.1249/01.mss.0000227310.18902.28.

Papathanasiou G, Georgoudis G, Georgakopoulos D, Katsouras C, Kalfakakou V, Evangelou A: Criterion-related validity of the short International Physical Activity Questionnaire against exercise capacity in young adults. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. 2010, 17: 380-386. 10.1097/HJR.0b013e328333ede6.

Ramirez-Marrero FA, Rivera-Brown AM, Nazario CM, Godriguez-Orengo JF, Smit E, Smith BA: Self-reported physical activity in Hispanic adults living with HIV: Comparison with accelerometer and pedometer. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2008, 19: 283-294. 10.1016/j.jana.2008.04.003.

Wolin KY, Heil DP, Askew S, Matthews CE, Bennett GG: Validation of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short among Blacks. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2008, 5: 746-760.

Cust AE, Armstrong BK, Smith BJ, Chau J, Van Der Ploeg HP, Bauman A: Self-reported confidence in recall as a predictor of validity and repeatability of physical activity questionnaire data. Epidemiology. 2009, 20: 433-441. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181931539.

Fogelholm M, Malmberg J, Suni J, Santtila M, Kyrolainen H, Mantysaari M, Oja P: International Physical Activity Questionnaire: Validity against fitness. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2006, 38: 753-760. 10.1249/01.mss.0000194075.16960.20.

Timperio A, Salmon J, Rosenberg M, Bull FC: Do logbooks influence recall of physical activity in validation studies?. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2004, 36: 1181-1186. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000132268.74992.D8.

Kolbe-Alexander TL, Lambert EV, Harkins JB, Ekelund U: Comparison of two methods of measuring physical activity in South African older adults. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 2006, 14: 99-114.

Egeland GM, Lejeune P, Denomme D, Pereg D: Concurrent validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) in an liyiyiu Aschii (Cree) community. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2008, 99: 307-310.

Ferguson CJ: An effect size primer: A guide for clinicians and researchers. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2009, 40: 532-538.

Trost SG, Pate RR, Sallis JF, Freedson PS, Taylor WC, Dowda M, Sirard J: Age and gender differences in objectively measured physical activity in youth. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2002, 34: 350-355. 10.1097/00005768-200202000-00025.

Metzger JS, Catellier DJ, Evenson KR, Treuth MS, Rosamond WD, Siega-Riz AM: Patterns of objectively measured physical activity in the United States. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2008, 40: 630-638. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181620ebc.

Qu NN, Li KJ: Study on the reliability and validity of International Physical Activity Questionnaire (Chinese Version, IPAQ) (in Chinese). Chinese Journal of Epidemiology. 2004, 25: 265-268.

Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, O'Brien WL, Bassett DR, Schmitz KH, Emplaincourt PO, et al: Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2000, 32: S498-S504. 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009.

Rzewnicki R, Auweele YV, De Bourdeaudhuij I: Addressing overreporting on the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) telephone survey with a population sample. Public Health Nutrition. 2003, 6: 299-305.

Sallis JF, Saelens BE: Assessment of physical activity by self-report: status, limitations, and future directions. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 2000, 71: S1-S14.

Strath SJ, Bassett DR, Swartz AM: Comparison of MTI accelerometer cut-points for prediction time spent in physical activity. International Journal of Sports Medicine. 2003, 24: 298-303.

Welk GJ, McClain JJ, Eisenmann JC, Wickel EE: Field validation of the MTI Actigraph and BodyMedia armband monitor using the IDEEA monitor. Obesity. 2007, 15: 918-928. 10.1038/oby.2007.624.

Acknowledgements

This research was part of the project "FAMILY: A Jockey Club Initiative for a Harmonious Society" funded by the Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript. PHL conducted the literature review and the abstraction of study data, and drafted the manuscript. DJM and THL contributed to the study conceptualization and manuscript preparation, and provided critical editorial input to the interpretation of the data. SMS conceived of the study, contributed to the literature review, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, P.H., Macfarlane, D.J., Lam, T. et al. Validity of the international physical activity questionnaire short form (IPAQ-SF): A systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 8, 115 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-8-115

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-8-115