Abstract

Thinking about the universe also includes thinking about hypothetical extraterrestrial intelligence. Two key questions arise: Why are we thinking about them in the first place? And why are we anthropomorphizing them? One possible explanation may be that the belief in extraterrestrials results from a subjective feeling of loneliness or the need for closure. Results of an online questionnaire (N = 130) did not reveal a confident and consistent correlation between personal feelings of aloneness or need for closure and belief in extraterrestrial life or intelligence. The same was true for the anthropomorphic representation of extraterrestrial intelligence. The belief in extraterrestrial life was negatively linked to frequent religious activity, and to a lesser and more uncertain extent, to the belief in extraterrestrial intelligence. As evidenced by their parameter estimates, participants demonstrated an intuitive grasp of the probabilities inherent in the Drake equation. However, there was significant variability in the solutions provided. When asked to describe hypothetical extraterrestrials, participants mainly assessed them in terms connoted with physical appearance, neutral to humans, and partially influenced by anthropomorphism. Given the severe limitations, we conservatively conclude that individual loneliness is indeed individual and does not break the final frontier, that is, space.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The Milky Way hosts 1011 to 4 × 1011 stars [1]. Yet, we do not know if there is anybody out there, i.e., if life beyond Earth exists. Methods to find out are limited by the astronomical distances of outer space. Even if we find a sign of extraterrestrial life or intelligence, the means to establish the first contact are restrained by the same distance factor. Hence, the optimistic affirmation of the existence of extraterrestrials often implies that the chances of establishing contact are meager [2].

This confronts the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) with a significant constraint. Recent theoretical and technological advances have shifted focus toward finding technosignatures as indicators of extraterrestrial civilizations rather than establishing reliable communication [3,4,5,6]. However, it was argued elsewhere that the possibility of establishing contact with the creators of these technosignatures might be a dwelling human fantasy [7].

Contemplating extraterrestrials precedes the science of SETI and dates back thousands of years [8]. And even in light of the unforgiving reality of the Einsteinian universe and its implication for first contact: the notion of a populated universe remained an issue of passionate debates and scientific discussions. The question arising here is: When the chance of finding and communicating with them is low, why do humans think and keep thinking about extraterrestrials in the first place?

While there is a large body of literature examining the cultural aspects of the portrayal of extraterrestrials [9,10,11,12,13,14,15], empirical studies examining the human representation of extraterrestrials and underlying belief structures are sparse. In one of the few examples, Swami et al. [16] showed that the belief in extraterrestrials is multifactorial, divided into three factors: conspiracy beliefs about a governmental cover-up of a past visit, the scientific aspect of the search, and the thinking about extraterrestrial life in general. In a later publication, the authors revealed the positive association between paranormal beliefs, openness to experience, and the belief in alien visitation and a subsequent cover-up [17]. While the belief in a cover-upped extraterrestrial visit implicates the general existence of extraterrestrial intelligence and life, this relationship does not necessarily hold the other way around: One can believe in extraterrestrial life without the notion of a past encounter with them. Therefore, Swami et al. [17] only examined a particular facet of the belief in extraterrestrial life. Dagnall et al. [18] eliminated the influence of belief in alien visitation and revealed a weak correlation between belief in extraterrestrial life and paranormal beliefs. The authors concluded that the general belief in extraterrestrial life differs from the more paranormal-influenced belief in alien visitation.

Another study by Routledge et al. [19] examined how the belief in extraterrestrials provides meaning. However, this study measured belief in extraterrestrial intelligence (ETI) by mainly using three questions from whom two examined either the belief in UFOsFootnote 1 or a governmental cover-up. Again, this is a mix of concepts and only one facet of the belief in extraterrestrial intelligence. UFOs can also be “identified” as weather phenomena or military prototypes and are, therefore, only partially linked to extraterrestrial intelligence and SETI [21, 22]. Moreover, it is plausible to consider extraterrestrial life beyond Earth without necessarily endorsing the notion of their visitation to our planet and any potential government concealment.

Taking a more theoretical approach, Bohlmann and Bürger [23] discuss the historical approach to extraterrestrial life. They question if humans can even bear being alone in the universe: “‘what are we wired for to look for?’” [23]. Building on this question and the intention to shine more empirical light on the rationale behind the belief in extraterrestrial life and intelligence, the present study examines if humans can tolerate the impression of (a cosmic) aloneness. If not, belief in extraterrestrials should be more pronounced in those individuals who suffer more from individual aloneness. Subsequently, these adverse feelings of loneliness may culminate bottom up towards a socio-cultural imagination and representation of life elsewhere in the universe.

Considering its vastness, space is a source of high uncertainty. Need for closure describes the multifaceted preference for situations and stimuli that are not uncertain, allow predictability, and provide information urgently [24, 25]. Although, from a theoretical perspective, extraterrestrials are extremely strange to us [7, 26, 27], the belief in them may be a method to cope with the vastness and ambiguity of outer space. A populated universe may be less of a “waste of space” [28] and an opportunity to avoid a potential existential crisis following the nagging question: `Of all the places in the world, why did life evolve on Earth?`

The present paper’s underlying research questions can be summarized as follows: RQ1 When I feel lonely, can affirmation of the question `Is there anybody out there?` Mitigate this feeling and comfort me? RQ2: Does the answer to the same question provide an opportunity to cope with the vastness of space and achieve closure with it?

2 Theory

2.1 Anthropomorphism and need for closure

Anthropomorphism refers to the attribution of human characteristics to non-human entities. It can be divided into two types: imaginative anthropomorphism, which involves visually depicting these entities in a human-like manner, and interpretative anthropomorphism, which assigns human emotions, motives, and behaviors to them [29].

When confronted with uncertain situations, anthropomorphism is more likely [30]. This is because anthropomorphism is said to depend on the motivation for effective evaluation of one’s environment. It is therefore linked to the need for closure [31]. Need for closure was initially defined as a set of stable interindividual differences that translate into the desire for order, structure, predictability, secure knowledge, decision-making, and discomfort with ambiguity [24]. Theory-wise, need for closure manifests in two main tendencies: The urgency to reach closure quickly and retaining it once achieved [32].

The extreme strangeness of extraterrestrials [7, 26] creates a high degree of uncertainty, which can be mitigated by anthropomorphism. We can observe an overly anthropomorphic display of extraterrestrials in cultural [13, 28, 33] and scientific contexts [23, 34]. Yet, due to the necessity to give extraterrestrials some form, imaginative anthropomorphism is more prevalent in the cultural than in the scientific context.

Anthropomorphic representation of extraterrestrials should be more likely if need for closure is high. Moreover, the presumed existence of extraterrestrial life forms can serve as a viable strategy for coping with the universe's incomprehensibly vast scale and age.

2.2 Loneliness and solitude

Humans are social beings. Relating to our species members is crucial for our survival, flourishing, and the emergence of what we identify as culture [35,36,37,38,39]. It is therefore not surprising that experiencing the objective or subjective absence of fellow humans, i.e., the feeling of loneliness, can cause severe damage to psychological and physiological health [40,41,42,43]. Loneliness is a prevalent issue. A Institute of Labor Economics publication reported that before the COVID-19 pandemic, 9% of the European population frequently felt lonely, and around 20% felt socially isolated [44].

Overall, methods to cope with loneliness differ among age groups and gender [45]. Strategies comprise accommodation, reflection, and social isolation but also proactive strategies like searching for social support [46, 47]. For a review, see [48]. Furthermore, given healthy and stable interactions and satisfaction, romantic relationships can ameliorate loneliness [48,49,50,51,52,53]. One rather special and childhood-related coping mechanism is creating an imaginary companion. Among various motivations, satisfying the need to relate is one aspect of such behavior [54].

However, the absence of other humans has not only negative consequences. While loneliness refers to the adverse feeling of being alone, solitude describes the pleasurable experience of being alone [55, 56]. This feeling can have positive and negative outcomes [57, 58]. Long and Averill [55] emphasized the advantageous nature of solitude not only for the individual but also on the societal scale. It becomes evident that the experience of being alone underlies complex psychological and contextual dynamics.

The “Big Question” [59]: “Are we alone?” is implicitly accompanied by “Is there anybody whom we can talk to?” As there is no consensual accepted scientific evidence for extraterrestrial life so far, one could tauntingly argue that extraterrestrials are the imaginary companion of adult SETI researchers. In general, we postulate that considering the possibility of extraterrestrial life may be a coping mechanism to alleviate the sensation of our cosmic aloneness. Conversely, for humans who enjoy being alone, the notion of a “Rare Earth” [60] should be less concerning or disturbing. Thus, individuals who report a high affirmation of aloneness (solitude) should demonstrate a lower belief in the existence of extraterrestrial life than people who do not enjoy being alone.

According to Epley et al. [31], anthropomorphism also has a social component. We animate non-human entities to feel less lonely. Therefore, we expect that people who experience the negative aspects of being lonely are likelier to should also tend to represent extraterrestrial intelligence as more human-like, i.e., more anthropomorphic.

2.3 Religiosity

Religions often posit an intentional creation of the universe by supernatural forces, coupled with the belief that individuals can establish a profound connection with these forces. As a result, religiosity presents a potential exit strategy for addressing one’s perceived loneliness and need for closure. If so, this mechanism may compete with the hypothetical ameliorative effect of the belief in extraterrestrial intelligence. Indeed, there are findings of a negative association between religiosity and the belief in extraterrestrial life [19, 61]. Moreover, religiosity mitigates loneliness [47, 62, 63] (but see also [64]) and was found to be positively associated with the need for closure [65].

2.4 Hypotheses

This study aimed to shine additional light on the tangible manifestation of the belief in extraterrestrial life and intelligence and its relation to facets of aloneness, need for closure, and religiosity. Considering the novelty of the issue and the limited existing research, our approach involves a combination of exploratory and confirmatory methods. We hoped to find initial support for our hypothesis that belief in life beyond Earth may serve as a way to alleviate aversive sensations of cosmic isolation and that belief in extraterrestrial life can satisfy the need for closure.

Drawing from the theoretical discussions aforementioned and recognizing the social element of anthropomorphism, we predict:

-

(A)

A positive association between subjective feelings of loneliness and the belief in extraterrestrial life and intelligence (1) and anthropomorphic representations of extraterrestrial intelligence (2). (cf. RQ1)

-

(B)

A negative association between subjective feelings of solitude (1) and relationship satisfaction and the belief in extraterrestrial life and intelligence (2). (cf. RQ1)

Suspecting that people belief in life beyond Earth because it provides cognitive closure for the astronomical dimension of space, as reflected in the general tendency of anthropomorphism, we predict:

-

(C)

A positive association between the need for closure and the belief in extraterrestrial life and intelligence (1) and the anthropomorphic representations of extraterrestrial intelligence (2). (cf. RQ2)

In accordance with established findings, we also predict:

-

(D)

A negative association between religiosity and the belief in extraterrestrial life and intelligence (1), a positive association between religiosity and the need for closure (2), and a negative relationship between religiosity and loneliness (3).

Our research design does not allow for any causal conclusions. Yet, it can provide initial evidence that other studies may build on.

3 Methods

3.1 Participants

As the psychological mechanisms postulated are believed to be broadly applicable, our target sample was not limited in this study. We conducted an online survey and distributed it over university communication channels and private networks. N = 131 persons completed it. We excluded one person due to a supposed lack of seriousness while completing the survey.Footnote 2 No other exclusions were made. Final sample: N = 130 (26 female, 104 male, MAge = 23.4, SDAge = 6.9, RangeAge = 16–57 years). Age-wise, all participants were legally entitled to consent to the collection and processing under EU directives. The sample consisted mainly of highly educated people – only three participants’ had an education below the High-School level. One hundred twelve subjects were university students at the time of the survey. Relationship status: n = 63 were single, n = 3 married, n = 61 were currently in a relationship, n = 1 divorced, and n = 2 answers were missing. Participants who studied psychology could apply for course credit upon completing the study.

The sample size was determined using a power analysis. However, due to a lack of documentation by the author responsible for conducting the study (NAD), details of the power analysis are missing. We can reconstruct from personal correspondence that such an analysis was run and that approximately 100 persons should be included. However, we can neither determine the initial configurations nor the respective outcomes. Orienting on the common practice from our lab, we hold the following parameter as likely to be implemented: Linear multiple regression, expected effect size f2 = 0.15 (medium), α = 0.05, 1-β = 0.8, number of predictors 10. Computed with G*Power 3.1.9.7 [66], these inputs yield a required sample size of N = 107. We are aware that this procedure is not ideal. Yet, we acknowledge the lessons learned through these unfavorable and unpleasant circumstances. Data were analyzed in one chunk, meaning that we did not add any further participants after stopping at N = 131.

3.2 Design & measurements

After consenting to the terms of data collection and analysis, participants answered stated demographic variables such as the highest obtained academic degree, gender, age, current status of employment, and relationship status. Next, participants completed questionnaires designed to assess different aspects of their loneliness, need for closure, belief in extraterrestrial life and intelligence, and their tendency to anthropomorphize extraterrestrial intelligence. Participants were given the voluntary option to describe how they imagined extraterrestrial intelligence, assuming the existence of such life forms. Lastly, participants completed their estimation of the famous Drake-Equation. All scales are described in the next section.

Based on the suggested 21-word solution [67], we state that we report all data exclusions, all manipulations, and all measures in the study. The survey language was German.

3.3 Measures used in the confirmatory analysis

3.3.1 Relationship satisfaction

Participants stated their satisfaction with their current relationship status on a 5-point Likert scale (1—dissatisfied to 5—satisfied).

3.3.2 Loneliness

Participants completed the Loneliness Scale for Children and Adolescents (LLCA) [68]. This instrument consists of four scales, measuring loneliness in peer (L-PEER) and parental (L-PART) relations as well as the positive affinity for aloneness (A-POS) and aloneness that is experienced negatively (A-NEG). Each scale has 12 items. Participants answered how often they experienced various situations and feelings (i.e., I feel isolated from other people. When I am alone, I feel bad, I want to be alone to do some things) on a 4-point Likert scale (0never to 3—often). Scale scores were summed, resulting in a possible scale score range of 0 to 36.Footnote 3

We translated the original version of the questionnaire into German. Marcoen et al. [68] constructed their questionnaire to target children and adolescents. Hence, we adapted some items' wording to our participants' assumed age. We assumed that most of our participants were currently studying at a university and, therefore, more unlikely to live with their parents. Hence, we changed the L-PART scale’s wording to reflect loneliness in family relations (L-FAM) instead of only concerning parental relationships. Furthermore, items mentioning “school” were altered into “workplace, university, and/or school.”

In a study comparing different loneliness measuring instruments, findings of Goossens et al. [69], using an adolescent sample, supported the multidimensional approach to loneliness and recommended using the LLCA to assess it. Maes et al. [70] used confirmatory factor analysis and revealed age-related mean differences across scales. Nevertheless, they found a good model fit for the four factors of the LLCA in a sample of college students (N = 1,108). They concluded that scores of the LLCA could be meaningfully compared across different age groups.

3.3.3 Need for closure

Need for closure was assessed using a translated version of the Need for close scale (NFCS) [24]. We followed the advice of Roets and van Hiel [25] and used their alternative scale for decisiveness while also not including the Close-mindedness scale. While the original scale framed decisiveness more as an ability, the revisited decisiveness scale emphasizes the need for decisiveness [25]. The remaining scales were: Need for order (10 items), discomfort with ambiguity (9 items), Decisiveness (6 items), and desire for predictability (8 items). Participants rated items on a 5-point Likert scale (1—do not agree to 5- fully agree).Footnote 4 Scores were summed so that higher values represent a more pronounced manifestation.

3.3.4 Religiosity

Religiosity was measured using the 5-item Duke University Religion Index (DUREL), an instrument developed for large samples [71]. It was chosen due to its shortness and three subscales measuring organizational religious activity (ORA; 1-item: “How often do you attend church or other religious meetings?”, 1—Never to 6- More than once/week), non-organizational religious activity (NORA; 1-item: “How often do you spend time in private religious activities, such as prayer, meditation or Bible study?”, 1 —Rarely or never to 6—More than once a day) and intrinsic religiosity (IR; sum score of 3-items: “In my life, I experience the presence of the Divine (i.e., God),” “My religious beliefs are what really lie behind my whole approach to life,” “I try hard to carry my religion over into all other dealings in life,” 1—definitely not true to 5—definitely true of me). We translated the DUREL to German and added other holy scriptures to the NORA item (Quran and Torah).

3.3.5 Belief in ETI/ETL

Participants were asked to state their belief about the probability of extraterrestrial intelligent lifeFootnote 5 and extraterrestrial life in general on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1—unlikely to 5—very likely. The existence of intelligent extraterrestrial life implies the existence of extraterrestrial life. However, the question assessing the latter explicitly mentioned the per se aspect and explained that this includes unicellular organisms.

3.3.6 Anthropomorphism

Participants were then asked to state how similar intelligent extraterrestrials would look to humans (imaginative anthropomorphism) and how similar their behavior and feelings would be to humans (interpretative anthropomorphism). These questions refer to the two types of anthropomorphism described by Fisher [29]. Ratings were given on a 5-point Likert scale 1—dissimilar to 5—similar.

3.4 Exploratory measures

3.4.1 Free text

Following, participants had the opportunity to fill out an optional question: “Under the proposition of extraterrestrial intelligence exists. How do you imagine their appearance? Which characteristics or traits do you consider likely?” People could state up to five short text answers.

3.4.2 Drake equation

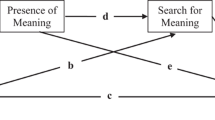

Interested in how relative laypersons estimate intelligent life’s prevalence in the universe, we asked participants to state their estimation of the famous Drake-Equation, estimating the number of galactic civilizations humanity can make contact with (N). First formulated in 1961 by SETI pioneer Frank Drake, this collection of essential aspects of the underlying search parameters of SETI is more of a heuristic than a precise equation [72]. N is not determinable because most parameters are unknown, and robust estimations are limited. Depending on the estimation conservatism, Schetsche and Anton [10] calculated an N-range from 0 up to 468,750. We visualize the equation in Fig. 1.

To constrain the estimation and ease the task, we predefined the R, fp, and ne to be 2.25, 1, and 0.05. These values reflect a “moderate” estimation by Schetsche and Anton [10]. These parameters were prefixed based on our perception that they necessitate significant expertise in astrophysics and biology and because scientists can reasonably estimate with precision [10, 73]. Participants were introduced to the logic of the equation, its parameters, and the prefixed values described above. After their input, participants were shown the result based on their estimation.

Our explanation of the parameters oriented at the original formulation of the terms by Frank Drake in 1961 [72]. The original terms state that the detectability of civilizations depends on them being capable of interstellar communication. However, rephrases of the meaning of N [e.g., 74] define it more according to extraterrestrials’ ability to produce remote detectable technological indices in general [cf. 6]. Our framing reflects the more orthodox approach to SETI that seeks mutual communication, and which was the predominant approach when the equation was first formulated [3].

3.4.3 General remarks

Original loneliness, need for closure scales, and the measure for religiosity can be found in the supplementary. Items are publicly available and can be found in [68] for the LLCA, [32] for the NFCS, and [71] for the DUREL. All p-values are two-sided.

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive statistics and internal consistency

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations are shown in Table 1. Internal consistency for the sample and the scales was as follows: Peer-related loneliness α = 0.85, 95% CI [0.82, 0.89], family-related loneliness (L-FAM) α = 0.93, 95% CI [0.92, 0.95], Aversion for being alone (A-NEG) α = 0.85, 95% CI [0.81, 0.89], Enjoying the feeling of solitude (A-POS) α = 0.83, 95% CI [0.79, 0.87], Need for order (NFCS-Order) α = 0.77, 95% CI [0.72, 0.83], Desire for predictability (NFCS-Predic.) α = 0.79, 95% CI [0.74, 0.84], Decisiveness (NFCS-Desc.) α = 0.75, 95% CI [0.68, 0.81], discomfort with ambiguity (NFCS-Ambig.) α = 0.57, 95% CI [0.46, 0.68], Intrinsic religiosity (DUREL-IR) α = 0.88, 95% CI [0.85, 0.92].

Frequency for non-religious activity: Rarely or Never (n = 90, 69.23%), Few times a month (n = 16, 12.31%), Once a week (n = 9, 6.92%), NORA 2 + Times a week (n = 4, 3.08%) and Daily (n = 11, 8.46%). Frequency of organizational religious activity: Never (n = 40, 30.77%), < = 1 × Year (n = 47, 36.15%), Few times a year (n = 29, 22.31%), Few times a month (n = 7, 5.38%), Once a week (n = 3, 2.31%) and > Once a week (n = 4, 3.08%).

4.2 Confirmatory analysis—Prediction of belief in extraterrestrial life and intelligence and their anthropomorphic representation

We calculated Bayesian linear regression models to test our hypotheses. Belief in extraterrestrial life or intelligence and anthropomorphic representation of extraterrestrial intelligence were employed as outcomes. Relationship satisfaction, measurements of loneliness, need for closure, and religiosity served as predictors.

Multiple models were constructed due to the advice not to include all three DUREL scales in the same model due to possible interference between the scales [71]. Hence, for each outcome, three models with one respective scale were calculated.

To adequately reflect the novelty of the extraterrestrial research subject, priors for the predictors were uniformly set to N(0,1). The only exception was the effect of religiosity on the belief in extraterrestrial intelligence and life. As Routledge et al. [19] report negative correlations between religiosity and the belief in ETI to range from − 0.13 to − 0.27, we chose a rather moderate estimation that does not exceed the expected effect of f2 = 0.15, which we assume to have underlied our power analysis. Hence, we set the prior for religiosity on each scale to be N(− 0.15,1). We chose the larger standard deviation to reflect that we used a different instrument to assess religiosity than Routledge et al. Prior for σ was set to Exp(1) to reflect that variance cannot be negative and higher values are unlikely. The models ran for four chains, 50,000 iterations with 25,000 warm-up draws each.

After evaluating model predictions, we observed that Gaussian models do not adequately reflect the left-skewness of belief in ETL and ETI. Thus, we specified the outcome distribution to be skew-normal distribution and calculated the models again. Comparison of model fit showed the superiority of the models that predicted belief in ETL and ETI but little to no difference for the prediction of anthropomorphism (See Supplementary). Skew normal models for belief and normal models for anthropomorphism are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

4.3 Confirmatory analysis—Relationship of the scales

To further elucidate the relationship between religiosity, need for closure, and loneliness, we calculated ordinal logistic regression with the organizational and non-organizational religious activity scales as outcomes, respectively, a linear regression predicting intrinsic religiosity.

Orienting on the direction of effects revealed by Ismail and Desmukh’s [63], priors for LLCA scales were universally set to N(− 0.544,1) for peer and family-related loneliness when predicting organizational and non-organizational religious activity and to N(0.15,1) when predicting intrinsic religiosity. This divergence results from ordinal logistic regression using log odds ratio as a coefficient. Both means reflect f2 = 0.15. Ismail and Desmukh’s study, however, did assess loneliness solely as negative feeling. So prior to an aversion against loneliness and enjoyment of being alone were set to N(0,1). Saroglou [65] examined religiosity in two dimensions: Classic religiosity, which comprises the sense of belonging and frequency of prayer, and openness to spirituality, which focuses more on the experience-related aspect. Overall, need for closure was positively associated with the first and more negatively associated with the second factor. We linked organizational and non-organizational religious activity to classic religiosity and intrinsic religiosity to openness to spirituality. Maintaining the direction of significant effects, priors were set to N(0.544,1) for intolerance of ambiguity, need for order, and need for predictability when organizational and non-organizational religious activity were the outcomes (Decisiveness = N(0,1)). When predicting intrinsic religiosity, priors were set to N(− 0.15,1) for decisiveness, need for order, and need for predictability (intolerance of ambiguity N(0,1)). Prior for σ was set to Exp(1) to reflect that variance cannot be negative and higher values are unlikely. Models ran for four chains, 50,000 iterations with 25,000 warm-up draws each. A skew-normal distribution showed a better fit than a normal distribution model in predicting intrinsic religiosity. Results are shown in Table 4.

4.4 Exploratory analysis—Belief in extraterrestrial life and intelligence and anthropomorphism

People believed significantly more in the existence of extraterrestrial life than intelligence, paired t(129) = 10.60, mean difference = 0.92, 95% CI [0.75, 1.10], p < 0.001, d = 0.89.

Out of N = 130, n = 117 (90%), respectively, n = 81 (62.3%) reported a 4 or 5 concerning the belief in extraterrestrial life or extraterrestrial intelligence. We labeled these individuals as Believers ETL, respectively Believers ETI.

Participants believed that extraterrestrial intelligence would be more similar to humans in terms of feeling and thinking (interpretive anthropomorphism) than appearance (imaginative anthropomorphism), paired t(129) = 3.33, mean difference = 0.28, 95% CI [0.11,0.44], p = 0.001, d = 0.29. Believers ETI neither deemed the appearance of hypothetical extraterrestrials t(128) = 0.76, mean difference = 0.13, 95% CI [− 0.21, 0.47], p = 0.45, d = 0.14, nor their alleged feeling and thinking t(128) = 1.40, mean difference = 0.25, 95% CI [− 0.10, 0.59], p = 0.16, d = 0.25, as more human-like than the other participants.

4.5 Exploratory analysis—insights into loneliness

Taking place during the Fall of 2020, data collection occurred in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the legal and moral commandment to practice social distancing. Hence, we further investigated the relation of loneliness scales among themselves. This was done to gain insight into the back-then loneliness profile and the psychological effects of the pandemic.

Participants experienced significantly less loneliness in terms of family relations than peer relations, paired t(129) = − 5.21, mean difference = − 3.79, 95% CI [− 5.23, − 2.35], p < 0.001, d = 0.58 and showed significantly less aversion for being alone than enjoying the feeling of solitude, paired t(129) = − 7.53, mean difference = − 5.32, 95% CI [− 6.72, − 3.92], p < 0.001, d = 0.90.

As the LLCA was initially developed for children and adolescents, we also explored the correlation between the scaled and age. There were no significant correlations: peer-related loneliness r = − 0.09, p = 0.319, family-related loneliness r = 0.08, p = 0.353, aversion for being alone r = − 0.04, p = 0.678, enjoying the feeling of solitude r = 0.02, p = 0.798.

4.6 Exploratory analysis—Drake-equation

We then analyzed the data for the estimation of the Drake-Equation parameters. Estimations, especially of civilizations’ lifetime (L) and, therefore, N, showed an enormous variance. Table 5 shows all descriptive values. We calculated “final” solutions of the Drake equation using the mean values of each estimation (rounded to three digits), respectively, the median. For further investigation, we formed a reasonable sample, excluding data of one participant who stated 1E + 12 years and one who stated fraction of intelligent life that develops technological communication abilities (FC) = 5%, but civilizations’ lifetime (L) being 0. This was done because 1E + 12 exceeds the universe's age (~ 14E + 9 years), and FC = 5% and L = 0 is highly improbable and implies that civilizations are destroyed once they achieve the capability for interstellar communication within one solar year. Three other participants also reported L = 0, but their FC values were also 0. Therefore, their answers were logically consistent. Results of all samples are shown in Table 6. Data from the reasonable sample was visualized in Fig. 2.

4.7 Exploratory analysis—free text answers on the representation of extraterrestrials

Two independent raters rated the qualitative answers on appearances and assumed traits. Based on the 287 answers received, they created a set of categories. Each answer was assigned to one category. In case of a disagreeing categorization, raters discussed the case and reached a consensus.

Additional categories were introduced to further explore the implicit relation between extraterrestrials and humans: Superior/inferior to humans and Hostility. In addition to their initial categorization, answers could be placed into these categories if they directly mentioned comparative characteristics (i.e., “more intelligent”) or mentioned if extraterrestrials would pose a threat to us.

Lastly, raters assessed the anthropomorphic nature of the answers by comparing them to human characteristics. Answers were categorized as “human-like” if they directly mentioned humans in a non-ordinal relationship or if the answer referred to an ability that humans possess. When answers stated things like “other [XY],” these were coded as non-human-like. One exception was the answer “other clothes,” as humans are the only known species that use clothes. Besides Human-like (i.e., “clothes,” “education,” or “any form of a visual apparatus”) and Non-human-like (i.e., “telepathy,” “other language,” “frog-skin”), we introduced a third category: Unclear. Answers in this category partially refer to a trait humans possess under a particular point of view. Still, it is unclear if the own species was the point of reference here (i.e., “capable of adaptation,” “some sort of sensual structures,” “living,” “legs,” “eyes”) or if humans really have this characteristic under a non-anthropocentric point of view (“highly developed,” “long fingers”). Any mention of intelligence was categorized as human-like, although we are aware of the anthropocentric pitfalls of such categorization and the confusion with the question asked. Yet, as we are the only known species that explicitly claims the intelligence label for itself, we assume an anthropomorphic motivation behind this explicit attribution. Two answers stated “not intelligent,” respectively “no way of thinking.” This contradicts the question which implied the existence of extraterrestrial intelligence. Acknowledging the plausibility that the provided answers may encompass a broader perspective on the presence of life in the universe and the inherent difficulty in ascertaining whether these answers exclusively pertain to extraterrestrial intelligence rather than extraterrestrial life, we refrained from excluding the given response.

One person stated three times that they have no notion of extraterrestrials. We summarized these answers as one instance of unclear strangeness, reducing the number of responses to 285.

Lastly, answers were asked if they explicitly referred to humans as the object of comparison. They were rated either as “Unlike” humans (i.e., “other language,” “unlike humans”), “Like” humans (i.e., “likely to have similar mental processes as humans (cognitive abilities)”), or Not comparable (i.e., “small,” “different”). Tables 7 and 8 show the categorization of the answers.

The only mention of a possible hostile attitude against humans occurred with a “character” answer and was “peaceful,” therefore the opposite of a hostile attitude. When it came to superiority or inferiority, six out of nine (66.6%) statements concerned the mental abilities of extraterrestrials (i.e., “more intelligent than humans,” “learns faster than a human”). At the same time, the remaining three answers stated a technological or general superiority (“Like a furtherFootnote 6 evolutionary form of humans,” “technologically far advanced,” “Superiority to humans”). None of the statements mentioned inferiority towards humans. To avoid an overly anthropocentric perspective, statements like “Microorganisms” were not assessed in terms of superiority.

5 Discussion

This study investigated a possible link between individual loneliness, need for closure, and the belief in extraterrestrial life, respectively, intelligence. Additional focus was put on the role of religiosity, anthropomorphism, free-text description of extraterrestrials, and estimation of Drake equation parameters. Employed linear models found little to no support for our hypotheses.

When predicting the belief in ETL and ETI, no predictor showed a consistent and certain link that supported our hypotheses. When assessing belief in ETL, direction of effects of different aspects of aloneness aligned with our predictions. However, nearly all of our effects were highly uncertain. This uncertainty is visible in the range of subsequent credible intervals and probabilities of directionality. Moreover, direction of effects even differed across models and outcomes.

We found a relatively certain positive link between intolerance of ambiguity and the belief in ETL, but not ETI. However, note that this scale’s internal consistency was poor and that the Bayes Factor suggests strong evidence against the possibility that this effect is more likely than being 0. Ratings on the revisited decisiveness scale showed the most certain and consistent negative relationship towards the belief in ETL. The direction of this relationship stands in direct opposition to our hypothesis. Prompted to explicitly rate their belief in extraterrestrial life, and given that the adapted scale reflects the need to decide [25], a possible conclusion is that individuals who received high scores on the scale were likely made assertions that align with current scientific knowledge, rather than unproven hypotheses. Yet, Bayes factor again suggests that this effect is likely not different from 0.

The only evidence in favor of our hypothesis was the effect of conducting organizational religious activity once a week on the belief in ETL and ETI. Note that this was specific to this factor. More frequent activity was not different compared to never conducting this sort of activity. This effect was much more uncertain and inconclusive regarding the belief in ETI. Seen in the context of religiosity, this finding is partially consistent with the preceding results [75]. While it is unlikely that the preaching and teaching in religious facilities commonly circle around the prevalence of extraterrestrial life, the institutional surrounding seems to be accompanied by a certain skepticism of this issue. Religious activity may be linked to a form of “geocentrism,” which can be described as harvesting the belief that Earth is the only inhabited planet in the universe [76].

The debate about the hypothetical presence of extraterrestrial life is a challenge for some, predominantly Western religions [77, 78]. Compared to other studies [16, 19, 61], we assessed concrete religious practice and not only the intrinsic religious dimension. This allows for a more nuanced picture of the negative relationship between belief in ETL and religiosity. For instance, Routledge et al. [19] report a negative correlation between religiosity (assessed as self-description in terms of religiosity and importance) and belief in ETI. However, their belief measurement mixed items about two different issues, namely the prevalence of extraterrestrial intelligent life and unidentified flying objects (UFOs) [16, 22, 76]. This could explain why they found a negative association with this facet of religiosity, and we did not.

Anthropomorphic representation (imaginative and interpretative) of extraterrestrials was consistently positively linked to intolerance of ambiguity. However, note again that this scale’s internal consistency was poor. We found a negative and relatively certain association between decisiveness and both types of anthropomorphism. Yet, the Bayes factor urged caution in interpreting this effect as support for our hypothesis. The same applies to the rather certain positive effect of the need for predictability on imaginative anthropomorphism. Why this relationship emerged is unclear. Prima facie predictability should be a feature of mental processes, not visual appearance. Overall, these findings yield little support for the theory of Epley et al. [31] and stand in opposition to results from different areas [79, 80].

Effects of the different facets of aloneness do not create a consistent picture either. Among the more certain effects was the more human-like representation of ETI when peer-related loneliness was high and enjoyment of solitude was low. In addition, interpretative anthropomorphism seemed to be positively linked to the aversion of being alone. Although these effects were somewhat consistent with our predictions, the direction of effects was uncertain, varied across types of anthropomorphism, and provided no clear support for being different than 0.

Overall we found no consistent and certain linear link between the need for closure and the belief in extraterrestrial life, intelligence, or its anthropomorphic representation. The same holds for the various facets of aloneness, i.e., solitude and loneliness. The inadequacy of our models is underscored by the suboptimal fit to the data.

Still, our data reveal some important differences between the belief in extraterrestrial life in general and extraterrestrial intelligence. Principal components analysis by Swami et al. [16] showed that items regarding these issues load on the same factor. Still, the astrobiological search for life elsewhere in the universe differs from SETI regarding financial funding, axioms, and methods [3, 7]. Cognitive highly developed extraterrestrial agents, as presupposed by SETI [7], depend on extraterrestrial life’s emergence and evolutionary process but not vice versa. Participants stated a higher belief in extraterrestrial life (90% reporting a 4 or 5 on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1—unlikely to 5—very likely) than in extraterrestrial intelligence (62.3% rating 4 or 5). Pettinico [75] revealed that around 60% of surveyed Americans believed in some form of extraterrestrial life, and Bainbridge [76] reported approximately 64% affirmation of the possibility of extraterrestrial intelligence. Recent studies surveying a cross-cultural sample of young adults report an even higher rate, showing up to 90% of participants believing that life exists elsewhere than Earth [81, 82]. The corollary between the existence of extraterrestrial intelligence and extraterrestrial life is evident. And yet, the associations between certain predictors, for example, religiosity and belief in ETL, do not unequivocally translate direction-wise and with the same level of certainty in the belief in ETI.

With estimations of the probability of life, intelligent life, and technological life consistently decreasing, estimations of the Drake equation further elucidate the differentiation between ETL and ETI. This seems to reflect an implicit notion of the participants on the many evolutionary hurdles life has to take to become “intelligent” and engage in space research [83,84,85,86]. Yet, positive correlations across the proportion of planets on which life emerges (FL), the proportion of this life becoming intelligent (FI), and the proportion which develops communication technology (FC) suggests that people tend to see the emergence of a communicating intelligent species as somewhat inevitable once life has formed. However, belief in ETL did not correlate significantly with FL; the proportion of suitable planets where life will eventually emerge. One possible interpretation would be that the belief in extraterrestrial life is a zero-or-nothing issue. Eventually, one instance is enough to prove the belief true, regardless of the number of planets on which it may happen. Believing that there is one instance of life out there does not come with the belief that there is plenty.

The lifetime of technological civilizations (L) is the most critical parameter in the Drake equation, therefore profoundly influencing the solution [87, 88]. Estimation of L varied tremendously, and it remains unclear if participants could grasp the equation's astrobiological and physical constraints. The highest value reported was 1 trillion years, which is greater than the current estimated universe’s age (~ 13.7 billion years). Although laypersons seem to have an intuitive notion of how certain parameters are conditional on others, some participants showed unrealistic expectations about the parameters’ magnitude.

Participants described potential extraterrestrial intelligence life overwhelmingly in terms of their hypothetical physical appearance and explicitly regarding their alleged color. The latter part is not surprising considering the important role of skin color in determining people identifying as “aliens” as different from belonging to other groups etc. [89, 90]. Given statements were often somewhat related to features humans possess but were too indistinctive to identify a straightforward anthropomorphic reasoning process. It would be overly inadmissibly anthropocentric to assume that statements like “just,” “motoric,” or “fearful” inevitably refer to humanity. Due to the limited context of the answers, categorization was challenging and should be interpreted cautiously. 35 out of 285 (12.3%) answers could be identified as possibly influenced by anthropomorphism. Of these 35 answers, 13 (37.1%) could be interpreted as referring to human-like appearance-related features and suggest an imaginative anthropomorphic attitude. On the contrary, ten human-like features discussed mental abilities, three social behavior, two character traits, and five cultural features. Taken together, these 20 answers (57.1%) could be interpreted as influenced by interpretative anthropomorphism [29]. The differing proportions are also reflected in the finding that participants believed that extraterrestrial intelligence would be more similar to humans in terms of feeling and thinking (interpretive anthropomorphism) than appearance (imaginative anthropomorphism).

However, when humans were directly or indirectly mentioned as reference subjects, 34 of 45 answers (75.6%) expressed dissimilarity rather than similarity. Note that not all answers rated as anthropomorphic directly or indirectly mentioned humans as the object of comparison. Overall, the data suggest that when demarking strangeness, people represent extraterrestrials under a primacy of appearance. The finding that people deem extraterrestrials more psychologically similar than physiologically further supports this argument. The primacy of visual representation could be a direct result of the item formulation but also be due to pop-cultural depiction of extraterrestrials. When movies and TV shows decide to show an alien, the acting of these extraterrestrials is often subjected to an interpretative anthropomorphic bias [23, 33, 34, 91]. Hence, the most apparent point of identifying the extraterrestrial as non-human lies in the visual sphere. In other words: When we all think the same, we can only be not alike if we look differently.

Interestingly, none of the answers directly mentioned a hostile or benevolent attitude toward humanity. This finding stands in contradiction to the two central positions in the Messaging extraterrestrial intelligence (METI) debate, where the arguments either circle around the possibility of receiving interstellar aid or qualifying as a target for an interstellar conquest [92,93,94]. Furthermore, the Messianic extraterrestrial and its hostile, Earth-destroying counterpart are recurrent archetypes in the cultural display of aliens [13, 14, 33]. However, within our study participants did not described extraterrestrials with any aggressive or messianic traits.

Separating the answers on the line of people who strongly affirmed the existence of extraterrestrial intelligence and the other participants revealed that the former group generated more descriptions (179; 62.8% vs. 106; 37,2%). In each group, 12.3% of these answers could be classified as influenced by anthropomorphism. 39.6% of the ETI Believers’ answers described features that were more non-human-like. Likewise, 43.3% of the other participants’ answers were classified as “non-human like.” When directly or indirectly employing humans as objects of comparison in their statements, 14.5% of the ETI Believers’ invoked a dissimilarity and 3.4% similarity. Values for the other participants were 7.5%, respectively 4.7%. Due to the limited context of these short answers, we refrain from any definitive interpretation of these findings. Still, regardless of their belief in ETI: Participants who decided to answer the free text question seemed to have the same impression that ETI are more strange than similar to us.

Concerning the relationship between the need for closure, loneliness, and religiosity, we found a negative link between organizational religious activity and family-related loneliness and a positive link between need for order and organizational religious activity. Effects of decisiveness and need for predictability on organizational religious activity were discernable but more uncertain. Note, however, that this sample consisted of rather unreligious people.

The data presented here do not support the hypotheses that people believe in extraterrestrial life or intelligence because they are lonely or have a high need for closure. Therefore, thinking about interstellar neighbors seems not to function as a universal coping strategy for individual loneliness. Results from Routledge et al. [19] suggest that a particular facet of the belief in extraterrestrial life can be a source of meaning. But cosmic meaning is not cosmic companionship. Individual loneliness seems to be genuinely individual and not cosmic.

6 Limitations and directions for future research

Our study has several limitations. First of all, applied instruments can be criticized. The empirical assessment of a hypothesized nomothetic experience of cosmic aloneness, using instruments developed for individual and earthly application, may be impossible. Internal consistency for some scales was poor, and the LLCA was not initially developed for use in populations with ages of > 18.

Most severely, we can only give limited information about how the sample size was determined. Although we deem it likely that sample size was determined in concordance with the estimations we commonly use at our lab, we cannot rule out the possibility that our sample size was too small and, thus, effectively underpowered.

Sample size limitations are additionally aggravated when considering the lack of belief variance. Nearly all participants strongly affirmed the possibility of extraterrestrial life. Underrepresentation of non-believers severely restricts generalizability and may have increased the uncertainty of parameter estimation intervals and diminished the quality of our models in general. The same applies to the different facets of religiosity.

The time of data collection (Fall 2020) occurred in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Then present containment measures such as social distancing and the aftermath of the first lockdown in Germany may have influenced the measurement of loneliness. Studies have revealed that compared to other age groups and pre-Covid times, young adults and students had a greater risk of feeling lonely and experienced more loneliness [52, 95, 96]. Our data showed that, compared to peer-related loneliness, participants experienced less family-related loneliness but could not find any age-related effect on the measures of loneliness. The latter aspect may be due to the age distribution of the sample (75% percentile = 24.8 years). Lack of age variety may have diminished the quality of the data. Young adulthood is a period of dealing with separation from parents and family, where respective individuals feel separated or detached from their parents and report higher levels of parental loneliness [97]. Due to disease containment strategies like distance learning or unemployment, students may have relocated back to their parents, shifting the social interaction away from their peers towards a more family-pronounced context, influencing the respective loneliness. Relocation to a family household can mitigate adverse outcomes of containment measures [98].

Furthermore, questions that assessed the social interaction at school, work, or university may be influenced by the limited possibility of social interaction in light of virtual learning and home office. It is possible that during the initial lockdown in Germany (March to May 2020), participants may have also cultivated a preference for alternative coping mechanisms. They may have resulted into an attitude shift toward being alone. Overall, the timing of the data sampling may have confounded our findings.

Those who did not believe in ETI may have had difficulties assessing the alleged appearance and psychological constitution of something they do not believe in. Even though anthropomorphism did not differ among believers and other participants, the underlying reasoning behind these ratings may have.

Free text answers may have been confounded with the questions’ wording, pronouncing an alleged focus on physical appearance. Nevertheless, participants also submitted descriptions of other characteristics.

Lastly, estimations of the parameters of the Drake equation revealed a tremendous variance concerning the mean lifetime of a technological civilization (L). Rendering N unrealistically large, this variance influenced the overall “solution” of the Drake equation. This somewhat supports other findings of insufficient estimations of humans regarding other contexts and variables which they do not have personal experience with (e.g., the altitude of a mountain in relation to the Earth’s radius, although the average of such estimations often yields good approximations [99]).

Given the recognized limitations of our study, we advocate for replication attempts in future research, utilizing a larger, more diverse sample size and employing improved psychometric measures to clarify the robustness and generalizability of our findings. Further research should also attempt to test our hypothesis more directly and employ a research design that allows for causal inferences. Besides experimental studies, qualitative methods could provide an in-depth understanding into the structure of the belief in extraterrestrial intelligence. Lastly, additional attention may be directed toward distinctively sampling populations that have significant experience with the overall topic, i.e., astrophysicists, astronomers, astrobiologists, and other SETI researchers.

7 Conclusion

In our study, we failed to find sufficient evidence to support the hypothesis that loneliness and the need for closure predict belief in extraterrestrial life or intelligence. Other findings shine limited light on the relationship between religiosity and the belief in extraterrestrial life. The empirical data on the nonprofessional estimation of the Drake parameters and free-text descriptions of extraterrestrials provide novel insights into the folk conception of extraterrestrial life and intelligence. Concrete SETI enterprises always depended on public opinion, especially in terms of monetary funding or computational power [100,101,102]. Understanding human attitudes toward SETI will enhance the ability to communicate with the public effectively.

Although the notion of extraterrestrials has already penetrated our psychological border [7], we do not know if there is actually anybody out there. However, the factual cosmic aloneness seems not to translate into individual loneliness and does not require coping by forcefully imagining a populated universe. Humans are lonely because they lack meaningful relations on Earth, not space. Yet, if extraterrestrials exist and a successful first contact occurs, this may be an opportunity for building such a meaningful “cosmic relationship.” Until then, we are left alone with our questions.

Data availability

Data can be found here: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/PNX68.

Notes

UFO stands for Unidentified Flying Object. This denomination is somewhat problematic, as it implies a causing “object”. Unidentified Aerial Phenomenon (UAP) coined by [20] is more precise and comprises weather and technological anomalies.

When asked for their sex, this person stated to be a "Japanese Battle Roboto".

68 (1987) state the possible range of their 4-point scales as 0 to 48 points. Yet, given that never corresponds to 0 and evenly scaling, often has to be coded as 3; 12 items necessarily result in the range we calculated. Later [69, 70] stated a 1 to 4 range of the items. We decided to use 0 as minimal value for the better representation of semantic meaning of “never.”.

The orginal scale used a 6-point Likert scale [24]. Due to a programming error occurring while building the online survey, we used a 5-point scale.

Using the concept of intelligence in an interstellar setting has been criticized by [7]. Yet, given the everyday notion of the Search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) we are using this concept to establish reflect the popular discourse of this issue.

The participant used the German word „weitere “ which can be translated as „another “ but also in terms of progress as we did here.

References

Masetti M. How Many stars in the milky way? 2015. https://asd.gsfc.nasa.gov/blueshift/index.php/2015/07/22/how-many-stars-in-the-milky-way/. Accessed 30 Jan 2023.

Döbler NA. Where will they be: hidden implications of solutions to the Fermi paradox. Int J Astrobiol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1017/S147355042200012X.

Bradbury RJ, Ćirković MM, Dvorsky G. Dysonian approach to SETI: a fruitful middle ground? J Br Interplanet Soc. 2011;64:156–65. https://doi.org/10.1038/184844a0.

Haqq-Misra J, Ashtari R, Benford J, Carroll-Nellenback J, Döbler NA, Farah W, et al. Opportunities for technosignature science in the planetary science and astrobiology decadal survey: arXiv. 2022.

Haqq-Misra J, Berea A, Balbi A, Grimaldi C. Searching for technosignatures: Implications of detection and non-detection. Bulletin of the AAS. 2019. 51.

Sheikh SZ. Nine axes of merit for technosignature searches. Int J Astrobiol. 2020;19:237–43. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1473550419000284.

Döbler NA, Raab M. Thinking ET: a discussion of exopsychology. Acta Astronaut. 2021;189:699–711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2021.09.032.

Dick SJ. Plurality of worlds the origins of the extraterrestrial life debate from democritus to Kant. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1982.

Küchler U, Mael S, Stout G, editors. Alien imaginations: Science fiction and tales of transnationalism. New York: Bloomsbury Academic; 2015.

Schetsche M, Anton A. Die gesellschaft der Außerirdischen: einführung in die exosoziologie the society of extraterrestrials: Introduction to exosociology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2019.

Schetsche M, Engelbrecht M, editors. Von Menschen und Ausserirdischen Transterrestrische Begegnungen im Spiegel der Kulturwissenschaft [About humans and extraterrestrials Transterrestric encounters in the mirror of cultural science. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag; 2008.

Benford G. Aliens and knowability: a scientist’s perspective. In: Slusser GE, Guffey GR, Rose M, editors. Bridges to science fiction. Carbondale, Ill: Southern Illinois University Press; 1980. p. 53–63.

Micali S. Towards a posthuman imagination in literature and media: monsters, mutants, aliens, artificial beings. Oxford: Peter Lang; 2019.

Ruppersburg h. The alien Messiah in recent science fiction films. J Popular Film Telev. 1987. https://doi.org/10.1080/01956051.1987.9944222.

Stonawksa M. 2016 Loving the alien How fictional alien invasions are helping us to be better humans. Magazyn antropologiczno-społeczno-kulturowy. 29: 167–79.

Swami V, Furnham A, Haubner T, Stieger S, Voracek M. The truth is out there: The structure of beliefs about extraterrestrial life among Austrian and British respondents. J Soc Psychol. 2009;149:29–43.

Swami V, Pietschnig J, Stieger S, Voracek M. Alien psychology: associations between extraterrestrial beliefs and paranormal ideation, superstitious beliefs, schizotypy, and the Big Five personality factors. Appl Cognit Psychol. 2011;25:647–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1736.

Dagnall N, Drinkwater K, Parker A. Alien visitation, extra-terrestrial life, and paranormal beliefs. J Sci Expl. 2011;25:699–720.

Routledge C, Abeyta AA, Roylance C. We are not alone: the meaning motive, religiosity, and belief in extraterrestrial intelligence. Motiv Emot. 2017;41:135–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-017-9605-y.

Raimer MA. THE WAR OF THE WORDS: Revamping operational terminology for UFOs. ETC: a review of general semantics. 1999. 56:53–9.

Harrison AA. The science and politics of SETI: how to succeed in an era of make-believe history and pseudoscience. In: Vakoch DA, Harrison AA, editors. Civilizations beyond earth: extraterrestrial life and society. Oxford: Berghahn Books; 2011. p. 141–58.

Hövelmann GH. Mutmaßungen über Außerirdische [Assumptions about extraterrestrials]. Zeitschrift für Anomalistik. 2009;9:168–99.

Bohlmann UM, Bürger MJ. Anthropomorphism in the search for extra-terrestrial intelligence—the limits of cognition? Acta Astronaut. 2018;143:163–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2017.11.033.

Webster DM, Kruglanski AW. Individual differences in need for cognitive closure. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:1049–62. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1049.

Roets A, van Hiel A. Separating ability from need: clarifying the dimensional structure of the need for closure scale. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2007;33:266–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206294744.

Schetsche M, Gründer R, Mayer G, Schmied-Knittel I. Der maximal Fremde. Überlegungen zu einer transhumanen handlungstheorie the strangest stranger. thoughts on a transhuman agency theory. Berliner Journal für Soziologie. 2009;19:469–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11609-009-0102-3.

Schetsche M. Auge in Auge mit dem Maximal Fremden? Kontaktszenarien aus soziologischer Sicht Eye to eye with the strangest stranger? Contact scenarios from a sociological perspective. In: Schetsche M, Engelbrecht M, editors. Von Menschen und Ausserirdischen: Transterrestrische Begegnungen im Spiegel der Kulturwissenschaft [About humans and extraterrestrials: Transterrestric encounters in the mirror of cultural science. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag; 2008. p. 227–53.

Hurst M. Dialektik des Aliens: Darstellungen und Interpretationen von Ausserirdischen in Film und Fernsehen Dialectics of the alien: Portrayals and interpretations of extraterrestrials in cinema and TV. In: Schetsche M, Engelbrecht M, editors. Von Menschen und Ausserirdischen: Transterrestrische Begegnungen im Spiegel der Kulturwissenschaft [About humans and extraterrestrials: Transterrestric encounters in the mirror of cultural science]. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag; 2008. p. 31–53.

Fisher JA. Disambiguating anthropomorphism an interdisciplinary review. In: Bateson P, Klopfer PH, editors. Perspectives in Ethology. New York: Plenum Publishing Corporation; 1991.

de Visser EJ, Monfort SS, McKendrick R, Smith AB, Melissa PE, McKnightKrueger F, Parasuraman R. Almost human anthropomorphism increases trust resilience in cognitive agents. J Experiment Psychol Appl. 2016;22:331. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000092.

Epley N, Waytz A, Cacioppo JT. On seeing human: a three-factor theory of anthropomorphism. Psychol Rev. 2007;114:864–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.114.4.864.

Roets A, van Hiel A. Item selection and validation of a brief, 15-item version of the need for closure scale. Personal Individ Differ. 2011;50:90–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.09.004.

Von EM. Aliens erzählen [Telling About Aliens]. In: Schetsche M, Engelbrecht M, editors. Von Menschen und Ausserirdischen: Transterrestrische Begegnungen im Spiegel der Kulturwissenschaft [About humans and extraterrestrials: Transterrestric encounters in the mirror of cultural science]. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag; 2008. p. 13–29.

Anton A, Schetsche M. Anthropozentrische Transterrestrik [Anthropocentric transterrestrics]. Zeitschrift für Anomalistik. 2015;15:21–46.

Deci EL, Ryan RM. The” what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq. 2000;11:227–68.

Flinn MV, Quinlan RJ, Coe K, Ward CV. Evolution of the human family Cooperative males, long social childhoods, smart mothers, extended kin networks. In: Salmon CK, Shackelford TK, editors. Family relationships an evolutionary perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007.

Bowlby J. Attachment and loss Attachment. London: Hogarth Press; 1969.

Tomasello M. Becoming human: a theory of ontogeny. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2019.

Tomasello M, Kruger AC, Ratner HH. Cultural learning. Behav Brain Sci. 1993;16:495–511. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0003123X.

Rico-Uribe LA, Caballero FF, Martín-María N, Cabello M, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Miret M. Association of loneliness with all-cause mortality A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:0190033. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190033.

Erzen E, Çikrikci Ö. The effect of loneliness on depression: A meta-analysis. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2018;64:427–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764018776349.

Ernst JM, Cacioppo JT. Lonely hearts: Psychological perspectives on loneliness. Appl Prev Psychol. 1999;8:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-1849(99)80008-0.

Park C, Majeed A, Gill H, Tamura J, Ho RC, Mansur RB, et al. The effect of loneliness on distinct health outcomes: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;294:113514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113514.

d’Hombres B, Barjaková M, Schnepf SV. Loneliness and social isolation: an unequally shared burden in Europe. SSRN Electron J. 2021. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3823612.

Rokach A. Strategies of coping with loneliness throughout the lifespan. Curr Psychol. 2001;20:3–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-001-1000-9.

Vasileiou K, Barnett J, Barreto M, Vines J, Atkinson M, Long K, et al. Coping with loneliness at University: a qualitative interview study with students in the UK. Mental Health Prev. 2019;13:21–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2018.11.002.

Rokach A, Orzeck T, Neto F. Coping with loneliness in old age: a cross-cultural comparison. Curr Psychol. 2004;23:124–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02903073.

Rokach A. Effective coping with loneliness: a review. OJD. 2018;07:61–72. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojd.2018.74005.

Lee C-YS, Goldstein SE. Loneliness, stress, and social support in young adulthood: does the source of support matter? J Youth Adolesc. 2016;45:568–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0395-9.

Pereira MG, Taysi E, Orcan F, Fincham F. Attachment, infidelity, and loneliness in college students involved in a romantic relationship: the role of relationship satisfaction, morbidity, and prayer for partner. Contemp Fam Ther. 2014;36:333–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-013-9289-8.

Lawal AM, Okereke CG. Relationship satisfaction in cohabiting university students: evidence from the role of duration of cohabitation, loneliness and sex-life satisfaction. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2021;16:134–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450128.2020.1842574.

Buecker S, Horstmann KT, Krasko J, Kritzler S, Terwiel S, Kaiser T, Luhmann M. Changes in daily loneliness for German residents during the first four weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc Sci Med. 2020;265:113541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113541.

Adamczyk K. An investigation of loneliness and perceived social support among single and partnered young adults. Curr Psychol. 2016;35:674–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-015-9337-7.

Gleason TR, Sebanc AM, Hartup WW. Imaginary companions of preschool children. Dev Psychol. 2000;36:419–28. https://doi.org/10.1037//0012-1649.36.4.419.

Long CR, Averill JR. Solitude: an exploration of benefits of being alone. J Theory Soc Behav. 2003;33:21–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5914.00204.

EP Galanaki. 2013. Solitude in children and adolescents a review of the research literature 50 79 88

Nguyen T-VT, Ryan RM, Deci EL. Solitude as an approach to affective self-regulation. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 2018;44:92–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167217733073.

Coplan RJ, Bowker JC, Nelson LJ. The handbook of solitude. Hoboken: Wiley; 2021.

Edmondson WH. Understanding the Search Space for SETI. In: Vakoch DA, editor. Communication with extraterrestrial intelligence. Albany: State of New York Press; 2011. p. 223–34.

Ward PD, Brownlee D. Rare earth: why complex life is uncommon in the universe. 2nd ed. London: Springer; 2003.

Vakoch DA, Lee Y-S. Reactions to receipt of a message from extraterrestrial intelligence: a cross-cultural empirical study. Acta Astronaut. 2000;46:737–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0094-5765(00)00041-2.

Rokach A, Chin J, Sha’ked A. Religiosity and coping with loneliness. Psychol Rep. 2012;110:731–42. https://doi.org/10.2466/02.07.20.PR0.110.3.731-742.

Ismail Z, Desmukh S. Religiosity and psychological well-being. Int J Bus Soc Sci. 2012;3:20–8.

Leondari A, Gialamas V. Religiosity and psychological well-being. Int J Psychol. 2009;44:241–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590701700529.

Saroglou V. Beyond dogmatism: The need for closure as related to religion. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2002;5:183–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670210144130.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang A-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3 1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41:1149–60. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149.

Simmons JP, Nelson LD, Simonsohn U. A 21 word solution. SSRN J. 2012. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2160588.

Marcoen A, Goossens L, Caes P. Lonelines in pre-through late adolescence: exploring the contributions of a multidimensional approach. J Youth Adolesc. 1987;16:561–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02138821.

Goossens L, Lasgaard M, Luyckx K, Vanhalst J, Mathias S, Masy E. Loneliness and solitude in adolescence: a confirmatory factor analysis of alternative models. Personality Individ Differ. 2009;47:890–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.07.011.

Maes M, Klimstra T, van den Noortgate W, Goossens L. Factor structure and measurement invariance of a multidimensional loneliness scale: Comparisons across gender and age. J Child Fam Stud. 2015;24:1829–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-9986-4.

Koenig HG, Büssing A. The duke university religion index (DUREL): a five-item measure for use in epidemiological studies. Religions. 2010;1:78–85. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel1010078.

Drake F, Sobel D. Is anyone out there? scientific search for extraterrestrial intelligence. New York: Delacorte Press; 1992.

Chick G. Biocultural prerequisites for the development of interstellar communication. In: Vakoch DA, editor. Archaeology, anthropology, and interstellar communication. Washington: National Aeronautics and Space Administration; 2014. p. 203–26.

Dick SJ. Cultural evolution, the postbiological universe and SETI. Int J Astrobiol. 2003;2:65–74. https://doi.org/10.1017/S147355040300137X.

Pettinico G. American attitudes about life beyond Earth: Beliefs, concerns, and the role of education and religion in shaping public perceptions. In: Vakoch DA, Harrison AA, editors. civilizations beyond earth: extraterrestrial life and society. New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books; 2011. p. 102–17.

Bainbridge WS. Cultural beliefs about extraterrestrials: A questionaire study. In: Vakoch DA, Harrison AA, editors. civilizations beyond earth: extraterrestrial life and society. Oxford: Berghahn Books; 2011. p. 118–40.

Lovin RW. Astrobiology and theology. In: Dick SJ, editor. Impact of discovering life beyond earth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2015. p. 222–33.

Traphagan JW, Traphagan JW. SETI in non-western perspective. In: Dick SJ, editor. Impact of discovering life beyond earth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2015. p. 299–307.

Nicolas S, Agnieszka W. The personality of anthropomorphism: How the need for cognition and the need for closure define attitudes and anthropomorphic attributions toward robots. Comput Human Behav. 2021;122:106841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106841.

Waytz A, Morewedge CK, Epley N, Monteleone G, Gao J-H, Cacioppo JT. Making sense by making sentient: effectance motivation increases anthropomorphism. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;99:410–35. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020240.

Chon-Torres OA, Ramos Ramírez JC, Hoyos Rengifo F, Choy Vessoni RA, Sergo Laura I, Ríos-Ruiz FGA, et al. Attitudes and perceptions towards the scientific search for extraterrestrial life among students of public and private universities in peru. Int J Astrobiol. 2020;19:360–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1473550420000130.

Persson E, Capova KA, Li Y. Attitudes towards the scientific search for extraterrestrial life among Swedish high school and university students. Int J Astrobiol. 2019;18:280–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1473550417000556.

Schulze-Makuch D, Bains W. The cosmic zoo: complex life on many worlds. Cham: Springer; 2017.

Döbler NA. The concept of developmental relativity: thoughts on the technological synchrony of interstellar civilizations. Space Policy. 2020;54:101391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spacepol.2020.101391.

Snyder-Beattie AE, Sandberg A, Drexler KE, Bonsall MB. The timing of evolutionary transitions suggests intelligent life is rare. Astrobiology. 2021;21:265–78. https://doi.org/10.1089/ast.2019.2149.

Ashkenazi M. Will ETI be space explorers? Some cultural considerations. In: Shostak S, (eds). 1995.

Denning KE. “L” on Earth. In: Vakoch DA, Harrison AA, editors. Civilizations beyond earth: extraterrestrial life and society. New York: Berghahn Books; 2011. p. 74–83.

Ćirković MM. The temporal aspect of the drake equation and SETI. Astrobiology. 2004;4:225–31.

MacLin OH, Malpass RS. Racial categorization of faces: the ambiguous race face effect. Psychol Public Policy Law. 2001;7:98–118. https://doi.org/10.1037//1076-8971.7.1.98.

Harsányi G, Carbon C-C. How perception affects racial categorization: on the influence of initial visual exposure on labelling people as diverse individuals or racial subjects. Perception. 2015;44:100–2. https://doi.org/10.1068/P7854.

Engelbrecht MSETI. Die wissenschaftliche Suche nach außerirdischer Intelligenz im Spannungsfeld divergierender Wirklichkeitskonzepte SETI the scientific search for extraterrestrial intelligence in the area of tension of diverging concepts of reality. In: Schetsche M, Engelbrecht M, editors. Von Menschen und Ausserirdischen: Transterrestrische Begegnungen im Spiegel der Kulturwissenschaft About humans and extraterrestrials: Transterrestric encounters in the mirror of cultural science. Bielefeld: Bielefeld transcript Verlag; 2008.

Denning KE. Unpacking the great transmission debate. In: Vakoch DA, editor. Communication with extraterrestrial intelligence. Albany: State of New York Press; 2011. p. 237–56.

Michaud MAG. Seeking contact: the relevance of human history. In: Vakoch DA, editor. Communication with extraterrestrial intelligence. Albany: State of New York Press; 2011. p. 307–17.

Brin GD. The search for extra-terrestrial intelligence (SETI) and whether to send “messages” (METI): the case for conversation, patience and due diligence. Journal of the Br Interpl Soc. 2014;67(8):16.

Bu F, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Who is lonely in lockdown? cross-cohort analyses of predictors of loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health. 2020;186:31–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.06.036.

Luchetti M, Lee JH, Aschwanden D, Sesker A, Strickhouser JE, Terracciano A, Sutin AR. The trajectory of loneliness in response to COVID-19. Am Psychol. 2020;75:897–908. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000690.

Majorano M, Musetti A, Brondino M, Corsano P. Loneliness, emotional autonomy and motivation for solitary behavior during adolescence. J Child Fam Stud. 2015;24:3436–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0145-3.

Husky MM, Kovess-Masfety V, Swendsen JD. Stress and anxiety among university students in France during Covid-19 mandatory confinement. Compr Psychiatry. 2020;102:152191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152191.

Carbon C-C. The earth is flat when personally significant experiences with the sphericity of the earth are absent. Cognition. 2010;116:130–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2010.03.009.

Billingham J. SETI: The NASA Years. In: Vakoch DA, editor. archaeology, anthropology, and interstellar communication. Washington: National Aeronautics and Space Administration; 2014. p. 1–21.

Korpela EJ. SETI@home, BOINC, and volunteer distributed computing. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci. 2012;40:69–87. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-earth-040809-152348.

Garber SJ. A political history of NASA’s SETI program. In: Vakoch DA, editor. Archaeology, anthropology, and interstellar communication. Washington: National Aeronautics and Space Administration; 2014. p. 23–48.

Acknowledgements