Abstract

Objective

We aimed to validate the Japanese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4-J). People in Japan, especially healthcare workers (HCWs) suffer from high rates of mental health symptoms. The PHQ-4 is an established ultra-brief mental health measure used in various settings, populations and languages. The Japanese version of the PHQ-4 has not been validated.

Methods

Two hundred eighty people in Japan (142 HCWs and 138 from the general public) responded to the PHQ-4-J. Internal consistency, and factorial validity were assessed using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and Multiple Indicators Multiple Causes (MIMIC) models.

Results

Internal consistency was high (α = 0.70–0.86). CFA yielded very good fit indices for a two-factor solution (RMSEA = 0.04, 95% CI 0.00–0.17) and MIMIC models indicated the performance differed between HCWs and the general population.

Conclusions

The PHQ-4-J is a reliable ultra-brief scale for depression and anxiety in Japanese, which can be used to meet current needs in mental health research and practice in Japan. Disaster research and gerontology research can benefit from this scale, enabling mental health assessment with little participant burden. In practice, early detection and personalised care can be facilitated by using the scale. Future research should target specific populations in Japan during a non-emergency time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

1.1 High rates of symptoms of mental health problems in Japan

Mental health symptoms such as depression and anxiety are the leading causes of health burden worldwide [1]. The global prevalence of mental health symptoms accounted for 655 million estimated cases in 1990, and 970 million cases in 2019, yielding an increase of 48% [2]. For decades, high rates of mental health symptoms have been consistently reported in Japan [3], with over half of Japanese people experiencing mental health symptoms [4].

Healthcare workers (HCWs) suffer from high rates of mental health symptoms. A systematic review and meta-analysis reported that the prevalence of burnout, depression, and anxiety among HCWs across 86 studies was 32%, 26%, and 25% respectively [5]. Mental health symptoms in HCWs can lead to diverse negative outcomes including poor patient care, treatment errors, and turnover intentions [6,7,8]. These negative outcomes often have financial implications such as increased treatment costs and staff recruitment/development costs [9, 10].

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has worsened the already-challenged mental health of HCWs worldwide, including in Japan [6, 11]. Studies conducted during the pandemic show that a wide range of mental health symptoms worsened [12], including elevated levels of stress [13, 14], depressive symptoms [15], insomnia [6], burnout [12], suicidal ideation [16], and loneliness [17]. For example, 50% of frontline HCWs experienced burnout [18]. Moreover, 62% of public health officials (e.g., public health nurses) suffered from job-related stress [15].

1.2 The patient health questionnaire-4

The Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) is an ultra-brief scale used to screen for anxiety and depression. It combines two items from the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; for symptoms of depression) and two items from the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7; for nervousness and uncontrollable worry) [19]. The PHQ-4 is a widely used, and highly reliable mental health measure, validated with a vast range of general population groups including people in Colombia [20], Germany [21], Greece [22], the Philippines [23], and in English and Spanish speaking Hispanic Americans [24]. Additionally, the scale has performed well with various age, gender, partnership status, and socioeconomic groups [25], and in different languages for refugees and migrants [26, 27].

PHQ-4 has also been validated in diverse clinical samples including pregnant women [28], pre-operative surgical patients [29], out-of-school adolescent girls and young women in Tanzania [30], and primary care setting patients [31]. The scale also correlates well with other mental health outcomes such as well-being [32], self-efficacy and life satisfaction [20]. Overall, evidence consistently supports the use of PHQ-4 for screening symptoms of depression and anxiety in a variety of global settings. However, to the best of our knowledge, PHQ-4 has not been validated in the Japanese language with a sample in Japan. Considering the high rates of mental health symptoms in Japan, detection of the symptoms and regular assessments are essential. The Japanese version of PHQ-4 (PHQ-4-J) needs to be validated.

1.3 Study aim

This study aimed to validate the PHQ-4-J. To achieve this, we investigated the reliability and validity of the PHQ-4-J, and its subscales PHQ-2 and GAD-2 in a sample of Japanese people. Specifically, we evaluated of the PHQ-4-J item characteristics, internal consistency, and factorial validity.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Study design and sample

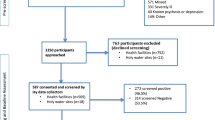

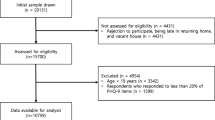

This is a post-hoc analysis of a longitudinal study evaluating changes of the mental health status in Japan during the pandemic [33]. HCWs and the general population were approached in Facebook groups in June 2020. Facebook is one of the most globally accessed social media platforms. In Japan there are 26 million active users, accounting for 12% of the population [34]. Two groups (> 1000 followers in June 2020) were chosen for recruitment because they were (a) active and well-managed (e.g., no abusive or discriminatory language used), and (b) none of the authors were a well-known figure in the group, limiting the biases. A survey link was embedded in the message we shared in the two groups. After consent was gained, participants were asked to complete the mental health scales. The survey was open for four weeks. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Derby Research Ethics Committee (ETH1920-2929). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. No financial incentive was offered for participation.

2.2 Measure

The original English version of the PHQ-4 is a validated measure asking how often you have been bothered by the following in the past two weeks: (1) Feeling nervous, anxious or on edge, (2) Not being able to stop or control worrying, (3) Feeling down, depressed or hopeless, and (4) Little interest or pleasure in doing things. The first two items assess anxiety, and the last two items assess depression. Each item is responded on a four-point Likert scale (0 = ”Not at all” to 3 = ”Nearly every day”). The total score is a sum of the four items (Range 0–12). Scores are interpreted as “normal” for 0–2, “mild” for 3–5, “moderate” for 6–8, and “severe” for 9–12 [19].

The PHQ-4 was first translated by YK, who is a professional translator between English and Japanese. The initial translation was back-translated into English by another bilingual researcher. No major difference was detected. The final version of the PHQ-4-J (please see Electronic Supplementary Material 1) was reviewed by the authors AO and HM, who were also English-Japanese bilinguals, to ensure that the wording was easy to understand by many Japanese people [35] and the content equivalence was maintained [36].

2.3 Data analysis

The item characteristics of the PHQ-4-J were calculated as measures of scale validity. These included the corrected item-total correlations, inter-correlations of items from the same subscale (J-PHQ-2, J-GAD-2), item-inter-correlations with items from the other subscale, and the intercorrelations between subscales and between each subscale and total PHQ-4-J scores. Since PHQ-4-J scores were not normally distributed, correlations were calculated using Spearman’s rho (ρ). Internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s α.

We used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to verify the known one- and two-factor structures of the PHQ-4. The comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis-Index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were the indices used to assess the model fit of the CFA. A CFI and TLI value > 0.95 [37], and RMSEA values < 0.10 indicate a good model fit [38]. Multiple Indicators Multiple Causes (MIMIC) models were used to examine associations between observed variables and latent variables [39]. Specifically, MIMIC models were used to assess associations between age group (≥ 34 years versus < 34 years, based on median split), gender, and group (general population versus HCWs) and scores on the PHQ-4-J (one-factor model), and the J-PHQ-2 and J-GAD-2 (two-factor model).

Data analyses were conducted in STATA 17.0 (Stata Corp LLP, College Station, TX).

3 Results

3.1 Sample characteristics

The sample used to evaluate the item characteristics, the internal consistency, and the factorial validity of the PHQ-4-J comprised 280 people. The mean age of the sample was 34.7 years (SD = 12.4) and 66.8% identified as female. 50.7% of the sample were HCWs. Median, mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis of PHQ-4-J, J-PHQ-2, and J-GAD-2 scores for the sample are provided in Table 1. The mean age of this subsample was 33.9 years (SD = 11.7) and 60.4% were female. 46.3% of this subsample were HCWs. Table 2 presents the frequency of use of each response per item.

3.2 Item characteristics

Corrected item-total correlations (i.e., correlations between a given item and the total PHQ-4-J sum score with that item removed) ranged from ρ = 0.57 to 0.63. Inter-correlations of items from the same subscale were ρ = 0.70 for the J-PHQ-2 and ρ = 0.48 for the J-GAD-2. The item-inter-correlations with items from the other subscale ranged from ρ = 0.43 to 0.55. The intercorrelation between subscales was ρ = 0.61 and correlations with total PHQ-4-J scores was ρ = 0.90 for the J-PHQ-2 and ρ = 0.89 for the J-GAD-2. All correlations were significant at p < 0.001. Tables 3 and 4 present these item characteristics.

3.3 Internal consistency

Cronbach’s α for the PHQ-4-J was 0.84. The Cronbach's α, if item dropped, varied from 0.75 to 0.83. Internal consistency for the J-PHQ-2 and the J-GAD-2 were 0.86 and 0.70 respectively.

3.4 Factorial validity

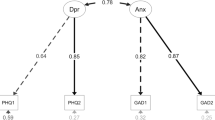

We used CFA to test the one- and two-dimensional structure of the PHQ-4-J. Factor loadings for the one-factor model were high (0.62–0.92). All indices except RMSEA indicated a good model fit for the one-factor model (CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.17, 95% CI 0.11–0.25). The two-factor model had an improved model fit (CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.04, 95% CI 0.00–0.17), with factor loadings ranging from 0.72 to 0.95. The MIMIC models for both the one- and two-factor structures are displayed in Fig. 1 (Age range scores are in Electronic Supplementary Material 2). Age and gender were not associated with scores on the PHQ-4-J, J-PHQ-2, or J-GAD-2. Group (i.e., general population versus HCW) was associated with the PHQ-4-J (0.16, p = 0.012) which indicated that HCWs had higher depressive symptoms. This suggests that the performance of the PHQ-4-J varied between the general population and HCWs in Japan. Looking at the J-PHQ-2 and J-GAD-2 separately revealed that HCWs had higher scores in both, but this was more pronounced for the J-GAD-2 (J-PHQ-2: 0.12, p = 0.046; J-GAD-2: 0.27, p < 0.001).

4 Discussion

Our study aimed to validate the PHQ-4-J. The results targeting the reliability and validity of PHQ-4-J were promising. The results of the current study indicate that it is a participant-friendly and reliable mental health measure in the Japanese language.

4.1 Implications for research

The PHQ-4-J can address some of the existing mental health research problems in Japan. One major area of concern is low response rates. For example, a nationwide survey, the World Mental Health Japan Survey, suffered from poor response rates: 55% for the 1st survey, and 43% for the 2nd survey [40]. This survey lasts an average of two hours [41]. Low response rates may lead to sample biases, because people who complete the measure may have a tendency that is relevant to the measured symptoms [42]. That is, completers of a lengthy mental health survey tend to be those who have experienced mental health symptoms, perhaps in turn making them more willing to invest their time in the survey [43, 44]. The PHQ-4-J, at only four items long, comprises little participant burden and therefore can address this problem.

The PHQ-4-J can also contribute to disaster research. Japan has experienced many types of natural disasters including earthquakes, floods, and typhoons. However, the mental health of people in Japan, including those who offer care, during these events remains under-researched [45]. This is important to address, because while the psychological impacts of these events are long-lasting, research has not been able to assess them [46]. An ultra-brief scale of the PHQ-4-J can help rectify this problem. People in a natural disaster are more likely to complete and repeat this four-item scale, compared to longer, more burdensome scales.

The proportion of older people (≧65 years old) has been rapidly increasing in Japan. In 2022, 29% of the national population were 65 years old or older, and this is set to increase [47]. Therefore, assessing older people’s mental health will become more prevalent. Gerontology research recommends the use of short scales for older people to reduce burden and assist their participation [48]. The PHQ-4-J is a short, and easy-to-understand scale, and therefore would likely be appropriate for use by this increasing population group.

The mean scores of our general population sample were similar to, and of our HCW sample were higher than those of the US sample (primary-care patients) in the original PHQ-4 development paper: Anxiety (two items) 1.4 ± 1.7, Depression (two items) 1.0 ± 1.4, and the total 2.5 ± 2.8 [49]. Consistent with other COVID studies [50,51,52], this may highlight the heightened mental distress among HCWs during the COVID pandemic. Additionally, the mean scores of our general population sample were lower than those of the US sample of general population during COVID: Mean and SD for anxiety (two items) 1.67 ± 1.97, for depression (two items) 1.60 ± 1.89, and for all four items 3.28 ± 3.67 [53]. The difference may be partly explained by the resilience of Japanese people to emergencies, including natural disasters (e.g., as seen in the “Bosai Culture” of Japan, referring to the ingrained attitudes and systems focused on disaster preparedness and resilience) [54, 55]. Many Japanese residents experience various natural disasters such as earthquakes, tsunamis, and floods, which may have made them mentally less affected by the pandemic compared to US residents [56]. Another explanation may be response biases derived from cultural differences [57]. Self-report measures can be susceptible to response biases [58]. People in the USA tend to give more extreme responses than people in Japan [59]. Moreover, shame towards mental health problems tends to be strong among Japanese people [60], relating to their perspectives to mental health [61]. For the global use of the PHQ-4, these differences need to be further evaluated [62].

Lastly, as the PHQ-4-J is a screening tool, the sensitivity and specificity to detect mental health problems need to be evaluated in future research. The sensitivity refers to how correctly the tool identifies a large proportion of individuals who actually have mental health problems, and specificity refers to how correctly the tool identifies a large proportion of individuals who do not have mental health problems [63]. These are essential for the effectiveness of screening tools [64].

4.2 Implications for practice

The PHQ-4-J can help mental health practice in four ways. Firstly, as a concise and non-intrusive questionnaire, the PHQ-4-J provides an easy approach for a HCW to open up a dialogue with the patient about their mental health. This is critical as mental health is a sensitive subject in Japan [57]. The PHQ-4-J can offer a safer way to discuss mental health with patients, especially those who are not seen for mental health concerns, as they may be more reluctant to talk about these issues [65].

Secondly, little patient burden to complete the scale can benefit HCWs too. HCWs often support patients to complete an assessment by responding to patient questions arising from the scale. The ultra-brief PHQ-4-J would require less HCW support for patients. HCWs in Japan are chronically understaffed [66]. For example, the number of nursing staff allocated to bed is markedly lower in Japan than in other countries: Japan 0.9, the UK 3.1, Canada 3.9, and the US 4.1 per bed [67]. Especially since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of people applying to healthcare roles has decreased, for reasons such as high workload. At the current pace, the healthcare workforce in Japan is expected to lack about two million workers by 2030 (12 million employed for 14 million needed) [68]. Little HCW burden to support patients completing the scale is also helpful in practice, reducing HCW workload.

Thirdly, the PHQ-4-J can be used at an intake session for early detection of mental health symptoms. Early detection of mental health symptoms is associated with improved patient outcomes, as appropriate treatments or referrals can happen sooner [69]. This prevents symptoms becoming worse with the potential development of more severe mental health symptoms [70].

Lastly, the PHQ-4-J is conducive to personalised treatment. A need for personalised treatment is increasing in many countries including Japan [71, 72]. To assess the impact of personalised treatment, regular assessments of patient mental health are needed [73]. Regular assessments also help identify possible adverse effects of the treatment. The PHQ-4-J is more well-suited for regular, repeated assessments, informing a development of personalised treatment.

4.3 Limitations

Several limitations need to be noted. First, the use of Facebook groups for recruitment may have caused sample selection bias such as judgmental and/or convenient sampling biases. Second, although our sample size is regarded as a “good” size [74], a larger sample would yield more generalisable results. Moreover, more specific populations instead of the general population could be explored in future research. We were unable to assess the construct validity of the PHQ-4-J and potential clinical cut-offs for depression and anxiety. Future research should seek to co-administer other measures of depression and anxiety alongside the PHQ-4-J, as well as gather information about mental health diagnoses in order to assess these aspects of the scale.

5 Conclusion

We validated the PHQ-4-J from HCWs and the general population in Japan. The PHQ-4-J has several research and practice implications, suggesting potential for the high utility of the scale in Japan. In research, the PHQ-4-J can help response rates by reducing burden, minimising, and also might lend itself to use in disaster research. In practice, the PHQ-4-J can help facilitate conversations about mental health with patients, HCW workload, early detection, and personalised treatment. Though the PHQ-4-J still needs to be tested in more specific populations, our findings provide evidence that the PHQ-4-J is a reliable ultra-brief scale for depression and anxiety in Japanese language which can be used to address current problems and needs in mental health research and practice in Japan.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Santomauro DF, et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398(10312):1700–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7.

GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(2):137–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3.

Kotera Y, Gilbert P, Asano K, Ishimura I, Sheffield D. Self-criticism and self-reassurance as mediators between mental health attitudes and symptoms Attitudes toward mental health problems in Japanese workers. Asian J Soc Psychol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12355.

Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. White paper about prevention of Karoushi and other issues [令和2年版過労死等防止対策白書. Tokyo: Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare; 2020.

Busch IM, Moretti F, Mazzi M, Wu AW, Rimondini M. “What we have learned from two decades of epidemics and pandemics: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychological burden of frontline healthcare workers.” Psychother Psychosom. 2021;90(3):178–90. https://doi.org/10.1159/000513733.

Kuriyama A, et al. Burnout, depression, anxiety, and insomnia of internists and primary care physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: a cross-sectional survey. Asian J Psychiatry. 2022;68:102956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102956.

Kotera Y. De-stigmatising self-care impact of self-care webinar during COVID-19. Int J Spa Wellness. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/24721735.2021.1892324.

Søvold LE, et al. Prioritizing the mental health and well-being of healthcare workers: an urgent global public health priority. Front Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPUBH.2021.679397.

Bae SH. “Noneconomic and economic impacts of nurse turnover in hospitals: a systematic review.” Int Nurs Rev. 2022;69(3):392–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12769.

Rachel Ann E, Elizabeth C, Dina J, Mark JS, Rita F. Economic analysis of the prevalence and clinical and economic burden of medication error in England. BMJ Quality Safety. 2021;30(2):96. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2019-010206.

Oladunjoye A, Oladunjoye O. An evolving problem—Mental health symptoms among health care workers during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;54:102257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102257.

Fukushima H, Imai H, Miyakoshi C, Naito A, Otani K, Matsuishi K. The sustained psychological impact of coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on hospital workers 2 years after the outbreak: a repeated cross-sectional study in Kobe. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):313. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04788-8.

Matsuo T, et al. Prevalence of health care worker burnout during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic in Japan. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2017271. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMANETWORKOPEN.2020.17271.

Shrestha RM, et al. The association between experience of COVID-19-related discrimination and psychological distress among healthcare workers for six national medical research centers in Japan. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02460-w.

Nishimura Y, Miyoshi T, Hagiya H, Otsuka F. “Prevalence of psychological distress on public health officials amid COVID-19 pandemic.” Asian J Psychiatr. 2022;73:103160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2022.103160.

Sato H, Maeda M, Takebayashi Y, Setou N, Shimada J, Kanari Y. Impact of unexpected in-house major COVID-19 outbreaks on depressive symptoms among healthcare workers: a retrospective multi-institutional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064718.

Kotera Y, Ozaki A, Miyatake H, Tsunetoshi C, Nishikawa Y, Tanimoto T. Mental health of medical workers in Japan during COVID-19: Relationships with loneliness, hope and self-compassion. Curr Psychol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01514-z.

Nishimura Y, Miyoshi T, Hagiya H, Kosaki Y, Otsuka F. Burnout of Healthcare Workers amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: a Japanese cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052434.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613–21. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613.

Kocalevent RD, Finck C, Jimenez-Leal W, Sautier L, Hinz A. Standardization of the Colombian version of the PHQ-4 in the general population. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:205. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244x-14-205.

Wicke FS, Krakau L, Löwe B, Beutel ME, Brähler E. Update of the standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2022;312:310–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.06.054.

Christodoulaki A, Baralou V, Konstantakopoulos G, Touloumi G. “Validation of the patient health questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) to screen for depression and anxiety in the Greek general population.” J Psychosom Res. 2022;160:110970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2022.110970.

Mendoza NB, Frondozo CE, Dizon J, Buenconsejo JU. The factor structure and measurement invariance of the PHQ-4 and the prevalence of depression and anxiety in a Southeast Asian context amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Psychol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02833-5.

Mills SD, Fox RS, Pan TM, Malcarne VL, Roesch SC, Sadler GR. “Psychometric evaluation of the patient health questionnaire-4 in Hispanic Americans.” Hisp J Behav Sci. 2015;37(4):560–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986315608126.

Löwe B, et al. A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2010;122(1–2):86–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.019.

Tibubos AN, Kröger H. “A cross-cultural comparison of the ultrabrief mental health screeners PHQ-4 and SF-12 in Germany.” Psychol Assess. 2020;32(7):690–7. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000814.

Kliem S, et al. Psychometric evaluation of an Arabic Version of the PHQ-4 based on a representative survey of Syrian refugees. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2016;66(9–10):385–92. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-114775.

Barrera AZ, Moh YS, Nichols A, Le HN. “The factor reliability and convergent validity of the patient health questionnaire-4 among an international sample of pregnant women.” J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2021;30(4):525–32. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2020.8320.

Kerper L, et al. Screening for depression, anxiety, and general psychological distress in pre-operative surgical patients: a psychometric analysis of the patient health questionnaire 4 (Phq-4). Clin Health Promot. 2014;4:5–14. https://doi.org/10.29102/clinhp.14002.

Materu J, et al. The psychometric properties of PHQ-4 anxiety and depression screening scale among out of school adolescent girls and young women in Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):321. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02735-5.

Mulvaney-Day N, et al. “Screening for behavioral health conditions in primary care settings: a systematic review of the literature.” J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(3):335–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4181-0.

Ghaheri A, Omani-Samani R, Sepidarkish M, Hosseini M, Maroufizadeh S. “The four-item patient health questionnaire for anxiety and depression: a validation study in infertile patients.” Int J Fertil Steril. 2020;14(3):234–9. https://doi.org/10.22074/ijfs.2020.44412.

Kotera Y, et al. A longitudinal study of mental health in healthcare workers in Japan during the initial phase of COVID-19 pandemic: comparison with the general population. Curr Psychol. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04444-0.

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. The 33 study meeting about platform services [プラットフォームサービスに関する研究会 (第33回) ]." "Ministry of Internal Affairs Communications. Tokyo: Ministry of Internal Affairs Communications; 2022.

Kotera Y, et al. Cross-Cultural Insights from Two Global Mental Health Studies: Self-Enhancement and Ingroup Biases. Int J Mental Health Addict. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-024-01307-y.

Asano K, et al. The development of fears of compassion scale Japanese version. PLoS ONE. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185574.

Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Mode. 1999;6:1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Schermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H, Müller H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. In: Methods of psychological research, vol. 8. Department of Psychology - University of Koblenz-Landau; 2003. p. 23–74. https://doi.org/10.23668/psycharchives.12784.

Chezan LC, Liu J, Drasgow E, et al. The quality of life for children with autism spectrum disorder scale: factor analysis MIMIC modeling, and cut-off score analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2023;53:3230–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-022-05610-2.

Ishikawa H, et al. “Prevalence, treatment, and the correlates of common mental disorders in the mid 2010’s in Japan: the results of the world mental health Japan 2nd survey.” J Affect Disord. 2018;241:554–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.050.

Kessler RC, Ustün TB. “The World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI).” Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):93–121. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.168.

Meiklejohn J, Connor J, Kypri K. “The effect of low survey response rates on estimates of alcohol consumption in a general population survey.” PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4):e35527. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035527.

Kotera Y, Conway E, Green P. Construction and factorial validation of a short version of the academic motivation scale. Br J Guidance Counsell. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2021.1903387.

Kotera Y, et al. Development of the Japanese Version of the original and short work extrinsic and intrinsic motivation scale. Jap Psychol Res. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpr.12551.

Kato H. Mental health care in a disaster [災害時の精神的ケアについて]. Chiyoda City: The Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology; 2023.

Shigemura J. “Lessons learned from the mental health consequences of the chernobyl and fukushima nuclear power plant accidents.” Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2021;18(2):107–8. https://doi.org/10.36131/cnfioritieditore20210205.

Statistics Bureau. Population data in November 2022 [人口推計 (令和4年(2022年)11月確定値]," in "Statistics Bureau. Tokyo: Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications; 2022.

Schwarz N, Park DC, Knaüper B, Sudman S. Cognition, aging, and self-reports (Cognition, aging, and self-reports). Hove: Psychology Press/Erlbaum (UK) Taylor & Francis; 1999. p. 407– xv.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Löwe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ–4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(09)70864-3.

Kotera Y, et al. Qualitative investigation into the mental health of healthcare workers in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(1):568. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010568.

Sasaki N, Kuroda R, Tsuno K, Kawakami N. “The deterioration of mental health among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 outbreak: a population-based cohort study of workers in Japan.” Scand J Work Environ Health. 2020;46(6):639–44. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3922.

Kotera Y, Kaluzeviciute G, Lloyd C, Edwards AM, Ozaki A. “Qualitative investigation into therapists’ experiences of online therapy: implications for working clients.” Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910295.

Adzrago D, Walker TJ, Williams F. Reliability and validity of the patient health questionnaire-4 scale and its subscales of depression and anxiety among US adults based on nativity. BMC Psychiatry. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05665-8.

K Gardiner. "Why are the Japanese so resilient?" BBC. https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20200630-why-are-the-japanese-so-resilient. Accessed 14 Aug 2024.

C Hagerty. "Japan Earthquakes: resilient architecture and disaster preparedness." National geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/japan-earthquakes-resilient-architecture-disaster-preparedness#:~:text=The%20country%20has%20earned%20a,on%20knowledge%20from%20previous%20disasters. Accessed 14 Aug 2024.

Tweed F, Walker G. Some lessons for resilience from the 2011 multi-disaster in Japan. Local Environ. 2011;16(9):937–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2011.617949.

Kotera Y, Van Laethem M, Ohshima R. Cross-cultural comparison of mental health between Japanese and Dutch workers: relationships with mental health shame, self-compassion, work engagement and motivation. Cross Cult Strategic Manag. 2020;27(3):511–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCSM-02-2020-0055.

Y Kotera et al. 2024. "How culture impacts recovery intervention: 28-country global study on associations between cultural characteristics and Recovery College fidelity." Preprint. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.34787.36648.

Lee JW, Jones PS, Mineyama Y, Zhang XE. Cultural differences in responses to a Likert scale. Res Nurs Health. 2002;25(4):295–306. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.10041.

Kotera Y, et al. “The development of the japanese version of the full and short form of attitudes towards mental health problems Scale (J-(S) ATMHPS),” Mental Health. Relig Cult. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2023.2230908.

Kotera Y, Taylor E. Defining the diagnostic criteria of TKS: unique culture-bound syndrome or sub-categories of existing conditions? Asian J Psychiatr. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2022.103383.

Kotera Y, Taylor E, Brooks-Ucheaga M, Edwards AM. Need for a tool to inform cultural adaptation in mental health interventions. ISSBD Bulletin. 2023;1(83):2–5.

Swift A, Heale R, Twycross A. “What are sensitivity and specificity?” Evid Based Nurs. 2020;23(1):2–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebnurs-2019-103225.

Park K, Yoon S, Cho S, Choi Y, Lee S-H, Choi K-H. Final validation of the mental health screening tool for depressive disorders: a brief online and offline screening tool for major depressive disorder. Front Psychol Original Res. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.992068.

CYI Chee, TP Nish, EH Kua. 2005."Comparing the stigma of mental illness in a general hospital with a state mental hospital." Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 40(8):648–653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-005-0932-z.

N. Ikegami, 2014. Universal Health Coverage for Inclusive and Sustainable Development : Lessons from Japan. (A World Bank study). Washington, DC.: World Bank,

Luft Medical Care. "Shortage of healthcare workers continues: The current status and causes [医療従事者の不足が止まらない!現状や原因を徹底解説]." Luft Medical Care. https://karu-keru.com/info/column/health-care-worker-lack. Accessed 12 May 2023.

Persol Research and Consulting. "Future labour market 2030 [労働市場の未来推計 2030]." Persol Research and Consulting. https://rc.persol-group.co.jp/thinktank/spe/roudou2030/. Accessed 12 May 2023.

Kessler RC, et al. “Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s world mental health survey initiative.” World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):168–76.

Kotera Y, Green P, Sheffield D. Mental health of therapeutic students: relationships with attitudes, self-criticism, self-compassion, and caregiver identity. Br J Guidance Counsell. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2019.1704683.

McMichael AJ, Kane JPM, Rolison JJ, O’Neill FA, Boeri M, Kee F. Implementation of personalised medicine policies in mental healthcare: results from a stated preference study in the UK. BJPsych Open. 2022;8(2):e40. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2022.9.

Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. "Basic knowledge about self-care for new employees [新入社員の方のためのセルフケア基礎知識]." Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. https://kokoro.mhlw.go.jp/newemployee/. Accessed 12 May 2023.

Sangruangake M, Summart U, Methakanjanasak N, Ruangsuksud P, Songthamwat M. “Psychometric properties of the thai version of supportive care needs survey-partners and caregivers (T- SCNS-P&C) for Cholangiocarcinoma Caregivers.” Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2022;23(3):1069–76. https://doi.org/10.31557/APJCP.2022.23.3.1069.

Boateng GO, Neilands TB, Frongillo EA, Melgar-Quiñonez HR, Young SL. Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: a primer. Front Public Health. 2018;6:149–149. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.K.; methodology, Y.K., I.B. and A.R.; software, Y.K., I.B. and A.R.; validation, all authors; formal analysis, I.B. and A.R.; investigation, all authors; resources, all authors; data curation, Y.K. A.O. and H.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.K., Y.K., J.J., J.B., K.B., I.B. and A.R.; writing—review and editing, all authors; project administration, Y.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical guidelines/Accordance: Our study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kotera, Y., Kameo, Y., Wilkes, J. et al. Validation of the Japanese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4-J) to screen for depression and anxiety. Discov Ment Health 4, 43 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44192-024-00093-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44192-024-00093-2