Abstract

Background

Healthcare workers who are exposed to coronavirus disease 2019 are psychologically distressed. This study aimed to evaluate the mental health outcomes of hospital workers 2 years after the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 and to identify changes in the stress of hospital workers and predicted risk factors.

Methods

This survey was conducted 2 years after the initial evaluation performed under the first emergency declaration of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic among hospital workers at the same hospital in an ordinance-designated city in Japan from June to July 2022. Sociodemographic data, 19 stress-related question responses, the Impact of Event Scale-Revised, and the Maslach burnout inventory-general survey were collected. Multiple regression models were used to identify factors associated with each of the mental health outcomes 2 years after the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak.

Results

We received 719 valid responses. Between 2020 and 2022, hospital workers’ anxiety about infection decreased, whereas their exhaustion and workload increased. Multiple regression analysis revealed that 2 years after the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak, nurses and young people were at a higher risk of experiencing stress and burnout due to emotional exhaustion, respectively.

Conclusions

This is the first study to examine the long-term stress of hospital workers measured in Japan. Exhaustion and workload were worsened 2 years into the pandemic. Therefore, health and medical institutions should continuously monitor the physical and psychological health of staff members.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

More than 100 million infections and 2 million deaths have been recorded worldwide due to the devastating global health crisis brought on by the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in 2020 [1]. As of November 2022, there were seven waves in Japan, with 22.7 million infections and more than 47,000 deaths [2]. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been devastating for patients and also healthcare workers. Working in a large tertiary hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic has been found to be stressful or traumatic for many healthcare workers [3]. On March 3, 2020, Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital (KCGH) admitted its first COVID-19-infected patient in Kobe. We have previously reported the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital workers under the first emergency declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan [4]. Although early studies have reported elevated rates of chronic stress, anxiety, and job burnout among healthcare workers, the longer-term impact of the pandemic is still largely unknown [5, 6].

The few studies, which explored the short-term impact of the pandemic on healthcare workers provide various results. A study on Argentinean healthcare workers showed a deterioration of self-perceived job performance and increased prevalence of depression and anxiety over a 4-month period [7]. In contrast, a study among intensive care unit nurses in Belgium showed that they had improved depression, anxiety, and somatization over a 2-month period [8].

To date, limited data is available on the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers over a more prolonged period. A repeated cross-sectional study on intensive care physicians in a COVID-19 hub hospital in Central Italy reported sustained high levels of occupational stress, anxiety, and depression, low satisfaction, and burnout over 1 year since the pandemic onset [9]. Some longitudinal studies have been reported during previous pandemics. For example, during the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003, healthcare professionals experienced high levels of posttraumatic stress symptoms that lasted for approximately 3 years [10, 11]. Future studies should analyze the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of hospital workers [12]. Patient-related stressful situations in these workers appear to be associated with burnout and posttraumatic stress disorder [13]. Therefore, understanding the enduring psychological effects of working during the COVID-19 pandemic is important since it involves the well-being of many hospital workers and, in turn, the effectiveness and safety of the care provided to patients [14].

On March 3, 2020, KCGH admitted its first COVID-19 infected patient in Kobe, and by the end of July 2022, 1,610 patients with severe COVID-19 had been admitted. During this period, seven waves of the pandemics were recorded, and we believe that hospital workers experienced more severe physical and psychological stress than ever before. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital workers 2 years after the outbreak and to identify personal and job-related factors that might have increased the risk of developing adverse mental health outcomes.

Methods

Study setting and participants

This was a two-point cross-sectional study targeting different populations while they were employed at the same hospital. Specifically, it represents the second evaluation conducted on the hospital workers of the KCGH. They were first assessed during the first emergency declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic (from April 16 to June 8, 2020). All staff working at KCGH during the COVID-19 pandemic were asked to participate. Employees who accepted to participate and signed a written consent form comprised the study’s sample. The findings of the first assessment are presented in detail elsewhere [4]. Four categories (Factor 1: anxiety about infection, Factor 2: exhaustion, Factor 3: workload, Factor 4: feeling of being protected) were identified as significant factors in the previous study [4]. Two years after the first assessment (from June 17 to July 31, 2022), hospital workers of the KCGH were invited to re-assess their psychological status. Similarly, to the first assessment, the evaluation conducted in 2022 was performed using self-rated scales hosted on a web-based survey (Google Forms), where participants could complete the online questionnaires using their personal computers, smartphones, or other mobile devices. This study was conducted under the same circumstances as the previous study, both respondents were allowed to be anonymous, therefore the data were unlinked. The study description and invitation to participate, as well as the link to the online questionnaires, were put up all over the hospital and sent via e-mail to all hospital workers. All employees were notified of the study information and purpose in accordance with the International Ethical Guidelines for Health-related Research Involving Humans; the disclosure document was sent via e-mail, and the employees were provided the opportunity to refuse participation. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of KCGH (no. zn220903).

Content of the questionnaire

The questionnaire explained the study’s purpose, which was to examine the stress experienced by hospital workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. It comprised items covering sociodemographic characteristics, stress-related questions associated with the COVID-19 outbreak, the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R), and the Maslach burnout inventory-general survey (MBI-GS).

Personal characteristics included gender, age group, job, and work environment during the COVID-19 pandemic. The respondents were asked if they had experienced the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake and whether they had participated in the Disaster Medical Assistance Team (DMAT). The work environment was categorized into frontliner (a respondent working in the ward for COVID-19 infection and the fever consultation center) and non-frontliner (a respondent working in any other place).

Overall, 19 questions related to stress were included (Table 1). The respondents indicated how frequently they experienced the conditions covered by these items during the pandemic using a 4-point Likert scale. The 19 items used in our study were based on similar items in a stress questionnaire used to study an influenza pandemic (H1N1) 2009 [15, 16].

The IES-R is a self-report measure of current subjective distress in response to a specific traumatic event. This 22-item scale comprises three subscales, which are representative of the major symptom clusters of post-traumatic stress as follows: intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal [17]. The respondent was asked to report the degree of distress experienced for an item in the past 7 days. The 5 points on the scale are as follows: 0 (not at all), 1 (a little bit), 2 (moderately), 3 (quite a bit), and 4 (extremely). The reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the IES-R have been verified. A cut-off score of 24/25 defined posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a clinical concern [18].

Burnout was assessed using the MBI-GS [19], which is a modified version of the original MBI [20] found to be reliable and valid across multiple cultural settings and occupations, including healthcare professionals [21,22,23,24]. It comprises 16 items with 7 response options that are answered on a Likert scale, from 0 (never) to 6 (every day). The Japanese version of the MBI-GS has been validated for the Japanese population [25,26,27,28]. This questionnaire contains three subscales that evaluate the three major domains of burnout, namely, emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and professional efficacy. The cutoff values for burnout are as follows: An Exhaustion score of > 3.5 and a Cynicism score of > 3.5 or an Exhaustion score of > 3.5 and a Professional Efficacy score of < 2.5 [29,30,31].

Statistical analysis

The participants’ characteristics were summarized as numbers and percentages and mean and standard deviation (SD) for the categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

During the H1N1 influenza pandemic, we performed an exploratory factor analysis and identified four factors for evaluation (anxiety about infection, exhaustion, workload, and feeling of being protected) using a stress-related questionnaire survey among hospital workers [15, 16]. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted, and we confirmed the same four-factor structure tested by the stress-related survey during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic [4]. Factor 1 comprised items 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, and 11, representing “anxiety about infection.” Factor 2 included items 14, 15, 16, and 17, indicating “exhaustion.“ Factor 3 consisted of items 3 and 4, which represented “workload.” Finally, Factor 4, which indicated a “feeling of being protected,” was based on items 9 and 10.

The total score of questionnaire items for each of the four factors was calculated. Here, each factor’s score, the IES-R, and MBI-GS were compared between strata of each personal characteristic using a Student’s t-test or analysis of variance. We also evaluated the association of personal characteristics with each score, the IES-R, and MBI-GS using multiple linear regression models. However, participants with missing data were excluded from the regression analyses. We compared the baseline characteristics of participants with and without burnout using the χ2 difference test. Results for each of the four factors of the 19 stress-related questions and the IES-R in 2020 and 2022 were compared using Welch’s t-test.

All analyses were performed using the R statistical software (version 4.1.0, Vienna, Austria) and SPSS 27 statistical package (IBM Corp. Released 2021, IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0., Armonk, NY).

Results

Overall, 798 employees completed the questionnaire from June 17, 2022 to July 31, 2022. Of these responses, 79 contained at least one missing answer, leaving 719 questionnaires (response rate: 22.5%) for analysis. In contrast, 1,111 healthcare workers participated in the first assessment from June 17, 2020 to July 31, 2022. Of the responses provided, 160 contained at least one missing answer, leaving 951 questionnaires (response rate: 29.6%) for analysis. Table 2 presents the characteristics of the valid respondents in 2020 and 2022. Jobs classified as medical doctor, nurse, or others (radiologic technologists, clinical laboratory technicians, pharmacists, dieticians, social workers, physical therapists, occupational therapists and speech therapists, biomedical equipment technicians, office workers, clinical clerks, guards, and janitors).

Mental health outcomes 2 years after the pandemic onset

Each of the four factors in the 19 stress-related questions and the IES-R at first (2020) and second (2022) assessment points were compared using Welch’s t-test (Table 3). Factor 1, “anxiety about infection,” was significantly lower in the second assessment point than the first (degree of freedom (df) = 1536.51, p < .001). Factor 2, “exhaustion,” and factor 3, “workload,” were significantly higher in the second than in the first (exhaustion: df = 1590.31, p < .001; workload: df = 1532.43, p < .001). Factor 4, which is the “feeling of being protected,” was significantly higher in the second than in the first (df = 1578.14, p < .001). The score in the second was higher than that in the first regarding the IES-R, although the difference was not significant.

Regression analysis

The data of 719 (22.5%) participants were included in the regression analysis. Table 4 presents the estimated associations of the sociodemographic characteristics with the total score for each of the four factors and the IES-R. The independent variables were gender, age group, job, exposure to COVID-19, the experience of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, and experience of engaging in DMAT. We investigated whether the experience of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake would be a factor of vulnerability in re-experiencing the trauma and if the experience of DMAT participation would be a protective factor through prior education. The dependent variables were factors 1, 2, 3, and 4 and the IES-R score.

Regarding gender, females reported higher levels of anxiety than males for factor 1, “anxiety about infection” (β = 1.18, p < .001). Nurses and others had higher levels of anxiety about infection than medical doctors for the job category (nurses: β = 1.30, p = .002; others: β = 1.69, p < .001). Related to exposure to COVID-19, the frontliners felt that they had higher levels of anxiety than the non-frontliners (β = 0.68, p = .010).

For factor 2, “exhaustion,” the scores did not vary by gender, age, job, exposure to COVID-19, experiences with the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, and experience of engaging in DMAT.

For factor 3, “workload,” workers in their 50s reported more demanding workloads than those in their 20s (β = 0.36, p = .044). Nurses reported that they had a greater workload than medical doctors (β = 0.83, p < .001). Concerning exposure to COVID-19, frontliners felt that they had a higher workload than non-frontliners (β = 0.75, p < .001). Workers who experienced the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake felt less workload than workers who did not experience it (β = − 0.34, p = .026).

For factor 4, “feeling of being protected,” the scores did not vary by gender, age, job, exposure to COVID-19, experiences with the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, and experience of engaging in DMAT.

The mean (SD) total score on the IES-R in the 719 participants was 13.9 (15.5), ranging from 0 to 88. Notably, 150 (20.9%) respondents were screened positive on clinical concerns for PTSD. The total IES-R scores varied by age and job in the regression analysis. The total IES-R scores of workers in their 30 and 50 s were lower than those of workers in their 20s (30s: β = -4.15, p = .012; 50s: β = -4.79, p = .010). Examined by job category, the total IES-R score of others was higher than that of medical doctors (β = 3.70, p = .041).

Burnout

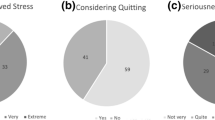

Overall, 123 (17.1%) employees satisfied the Japanese Version of the MBI-GS burnout criteria. Table 5 summarizes the results of the detailed demographic data for the burnout group. Thirty-three (15.6%) males and 90 (17.7%) females experienced burnout, but no significant difference was found in the prevalence of burnout between males and females (p = .501). Of the 166 nurses and 448 others, 38 (22.9%) and 67 (15.0%) experienced burnout, respectively. Significant differences were not observed between the two groups in the proportion of age (p = .126), job (p = .068), and exposure to COVID-19 (p = .456).

Table 6 lists the estimated associations of the sociodemographic characteristics with the MBI-GS subscale scores. The independent variables were sex, age group, job, exposure to COVID-19, experience of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, and experience of engagement in DMAT. The dependent variables were emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and professional efficacy.

In the regression analysis, significant differences were found between males and females in emotional exhaustion, with females presenting higher scores than males (β = 1.72, p = .025). Additionally, significant interaction effects were found between emotional exhaustion and age, where emotional exhaustion was greater in workers in their 20s than in those aged ≥ 40 (40s: β = -2.22, p = .013; 50s: β = -3.80, p < .001; 60s: β = -5.83, p < .001).

Significant differences were found between cynicism and age, with workers in their 60s reporting feeling more cynicism than those in their 20s (β = 3.55, p = .003). Additionally, significant interaction effects were observed between cynicism and job. Medical doctors had higher scores than nurses and others (nurses: β = -4.91, p < .001; others: β = -4.85, p < .001).

Significant differences were observed between professional efficacy and age, with professional efficacy scores being higher in workers in their 20s than in those in their 30s, 40s, 50s, and 60s (30s: β = -1.92, p = .008; 40s: β = -1.91, p = .011; 50s: β = -3.66, p < .001; 60s: β = -3.00, p = .015). Regarding the experience of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, workers who experienced it felt more professional efficacy than those who did not (β = 1.45, p = .037).

Discussion

This study assessed the psychological status of hospital workers 2 years after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The KCGH has been designated for the severe COVID-19 hospital since the beginning of the pandemic, and hospital care workers have continually provided care to both patients with COVID-19 and all other patients presenting with various medical and surgical conditions in a very difficult context characterized by the seven subsequent pandemic waves. We found that the mental health of hospital care workers deteriorated over the 2 years since the COVID-19 pandemic onset. Overall, we found that hospital workers are emotionally exhausted because of the great workload during the past 2 years, despite their perception of decreased infection anxiety and a sense of increased protection compared with previously. The study indicated that among healthcare workers, women, nurses, and frontline workers still faced multiple high-risk factors. We also found that healthcare workers in their 20s were emotionally exhausted, which is a risk factor for burnout.

Stress and gender

Here, females experienced higher levels of anxiety than males. In contrast, “exhaustion,” “workload,” “feeling of being protected,” and the IES-R scores did not significantly differ between genders. Similar results have also been previously reported. The female gender has been consistently associated with higher levels of anxiety [32,33,34,35,36,37,38], whereas no consistent association has been found with PTSD [39]. Therefore, women were more susceptible to anxiety and appeared to require more attentive care.

Stress and age

Here, the IES-R scores were significantly higher for workers in their 20s than for those in their 30 and 50 s. Other studies also showed that younger healthcare workers had a greater risk of developing PTSD [3, 11, 32, 40, 41]. Young workers might be more vulnerable when they face difficult situations such as patients suffering and dying from COVID-19, especially in cases where they are unable to provide the standard medical care due to limited resources [42]. Therefore, managers and executives should consider that younger workers are prone to stress. Since younger workers require care, it is important to create a workplace where they feel comfortable sharing their concerns.

Stress and profession

Examined by job category, nurses and others were significantly more anxious about infection. The reported “workload” was significantly higher for nurses than for medical doctors. However, nurses are particularly vulnerable to psychological distress in the workplace since most of them have experienced sudden and dramatic challenges in increased workload, reassignment to other roles or duties, and infection threats during the COVID-19 pandemic. Similar results were reported in studies of the 2003 SARS outbreak [43, 44] and the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 in Japan [16]. Another study of the COVID-19 pandemic yielded similar results [4, 32, 45]. Nurses are more likely to develop anxiety [46] and stress [47]. Furthermore, the amount of time spent with infectious patients may explain the difference in job effects. Therefore, establishing a limit on the amount of time spent with infectious patients may be necessary. Moreover, if more technology could be used, such as the introduction of nursing robots, it may be crucial to allow indirect contact with infectious patients.

Stress and place of posting

Hospital workers in high-risk environments (frontliners) experienced significantly higher levels of “anxiety about infection” and “workload” than those in low-risk work environments (non-frontliners). A systematic review by Serrano-Ripoll et al. found that working in a high-risk environment was associated with various mental health problems [39]. Therefore, increasing the number of staff in high-risk environments and reducing their workload would be necessary, as well as establishing a salary gradient between frontliners and non-frontliners.

Burnout

This study, conducted in 2022, showed that 17.1%, 17.1%, and 22.9% of hospital workers, physicians, and nurses experienced burnout based on the Japanese version of the MBI-GS. Using the MBI, other studies showed the prevalence of burnout – Spanish healthcare workers (15–82%) [48], Italian healthcare workers (25–53%) [49], and Wuhan healthcare workers (13–61%) [50]. We believe that the difference in the prevalence of burnout between these studies was influenced by the differences in the year of investigation, index of burnout, situation of the COVID-19 pandemic, and medical care system during the COVID-19 pandemic. Regarding the study of burnout among hospital workers using the Japanese version of the MBI-GS, a study in April 2020 showed that 31.4%, 13.4%, and 46.8% of hospital workers, physicians, and nurses, experienced burnout, respectively [29]. Moreover, another study, which was conducted after the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan, showed that 22.6%, 9.8%, and 29.4% of hospital workers, physicians, and nurses experienced burnout, respectively [31]. The difference in the prevalence of burnout among hospital workers in Japan may be influenced by the differences in the year of investigation and the situation of the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, our hospital provided the regular message of protection, comfort, and appreciation from the director and infection control team (ICT) of the hospital, updated information about the virus through the top page of the electronic health record system, quick opening of the consultation service for staff, and hotels for those who could not return home. Furthermore, the hospital mailed a package with a message from the director of the nursing department as well as advice on self-care during the break from the ICT for those who were absent from work due to the COVID-19 infection. During the period when eating out was restricted, the director invited food trucks for lunch breaks, which was well received by the staff. Therefore, these efforts may have contributed to the low burnout rate among hospital workers.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, hospital workers experienced various stresses, such as increased workload and performing new task, which was usually not done [45]. Burnout represents a great concern for healthcare staff working in a large tertiary hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic, and its impact is more burdensome for young workers [29]. Here, emotional exhaustion was also greater in workers in their 20s than in those aged ≥ 40 years. This might be related to the fact that young workers are less familiar with infection control and protective measures and have less experience dealing with extreme events such as a pandemic [51]. Hospital workers with more clinical experience amounts to being better prepared for epidemics, which, in turn, may be conducive to enhanced stronger self-regulation ability [52]. Over time, they might also have come to develop individual coping strategies for increased workloads.

Overall, the findings of this study, combined with the results obtained from the same hospital population during the first pandemic wave [4], suggest that the psychological reaction of hospital care workers to the challenge posed by the COVID-19 pandemic differs according to the specific stage of the pandemic. At the beginning of the first wave, an ‘acute stress’ reaction was observed, which was characterized by a posttraumatic response, fear of contagion, and anxiety [14]. Two years after the pandemic onset, after having dealt with difficult working conditions determined by the sixth pandemic waves, a ‘chronic stress’ reaction appears to have emerged, characterized by increased exhaustion and workload. Therefore, healthcare systems will need to address the pandemic’s psychological impact on hospital care workers by monitoring reactions and performance, paying careful attention to assignments and schedules, assessing occupational risk, and providing psychological support services for those in greater need of mental healthcare [53].

This study had some limitations. The first limitation of our study is the non-response bias as a result of the 22.5%. The response rate was low for both surveys (29.5%, and 22.5%, respectively). However, the results of this study were more consistent with previous studies and seemed to reflect the mental health of hospital workers. Another possibility is that health care workers may be more stressed and have higher scores on the IES-R than the results of the current study because exhausted people are less likely to respond. Second is the external validity as the present study was conducted at a single facility. However, the present results have commonality with the studies conducted in other cities in Japan [29, 31, 54]. They showed that female, nurse compared with doctors felt more event-related distress and burnout.This commonality may indicate that the present results have external validity in some way. Third, we did not assess other common mental states such as depression. However, IES-R total score were associated with depressive symptoms in a previous study [55], and the IES-R scores may reflect the mental health of the staff. Fourth, this was a two-point cross-sectional study targeting different populations while they were employed at the same hospital. Two points in 2020 and 2022 under different COVID-19 situations with different populations cannot be used to accurately extrapolate long-term influence on mental health. Fifth, although we identified four categories (F1 - F4) as significant factors in the previous study, the association between the four categories and job outcomes, such as absence from work, has not been investigated. A systematic review by Meredith et al. found that workplace factors such as workload, work/life balance, job autonomy, and perceived support from leadership were strongly associated with the risk of burnout [56]. In this study, workload and feeling of being protected were also identified as significant factors, work/life balance and job autonomy should be investigated in a future study.

In this pandemic, COVID-19 treatment has been mainly provided by large hospitals such as ours. Therefore, it is important to quickly disseminate a package of solid infection control knowledge, techniques, and equipment to private clinics as well as to share the workload between hospitals and clinics. Furthermore, the burden of COVID-19 treatment, which was placed on a limited number of hospitals, may be problematic; therefore, management is needed among hospitals and clinics to ensure that stress is not placed only on those hospitals involved in COVID-19 treatment.

Conclusion

Exhaustion and workload among hospital workers have further deteriorated 2 years after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, hospital workers are under unprecedented strain because of the long duration of the pandemic. This study showed that women, those in their 20s, nurses, and frontline workers have a high risk of experiencing stress and burnout. Therefore, health and medical institutions should closely monitor the physical and psychological health of their staff members.

Data availability

The dataset supporting the conclusion of the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CFA:

-

confirmatory factor analysis

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus Disease 2019

- DMAT:

-

Disaster Medical Assistance Team

- ICT:

-

Infection Control Team

- IES-R:

-

Impact of Event Scale-Revised

- MBI-GS:

-

Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey

- PTSD:

-

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

- SARS:

-

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

References

Worldometer [Internet]. COVID-19 Coronavirus pandemic. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/. Accessed 26 Jan 2021.

Worldometer [Internet]. COVID-19 Coronavirus pandemic. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/japan/. Accessed 8 Nov 2022.

Carmassi C, Foghi C, Dell’Oste V, Cordone A, Bertelloni CA, Bui E, et al. PTSD symptoms in healthcare workers facing the three coronavirus outbreaks: what can we expect after the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292:113312.

Fukushima H, Imai H, Miyakoshi C, Miyai H, Otani K, Matsuishi K. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital workers in Kobe: a cross-sectional survey. PCN Rep. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/pcn5.8.

De Kock JH, Latham HA, Leslie SJ, Grindle M, Munoz SA, Ellis L, et al. A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers: implications for supporting psychological well-being. BMC Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-10070-3.

Santabárbara J, Bueno-Notivol J, Lipnicki DM, Olaya B, Pérez-Moreno M, Gracia-García P, et al. Prevalence of anxiety in health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid systematic review (on published articles in Medline) with meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;107:110244.

López Steinmetz LC, Herrera CR, Fong SB, Godoy JC. A longitudinal study on the changes in mental health of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry. 2022 Spring;85:56–71.

Van Steenkiste E, Schoofs J, Gilis S, Messiaen P. Mental health impact of COVID-19 in frontline healthcare workers in a belgian tertiary care hospital: a prospective longitudinal study. Acta Clin Belg. 2022 Jun;77:533–40.

Magnavita N, Soave PM, Antonelli M. A one-year prospective study of work-related mental health in the intensivists of a COVID-19 hub hospital. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:9888.

Bai Y, Lin CC, Lin CY, Chen JY, Chue CM, Chou P. Survey of stress reactions among health care workers involved with the SARS outbreak. Psychiatr. Serv. 2004;55:1055–7.

Wu P, Fang Y, Guan Z, Fan B, Kong J, Yao Z, et al. The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54:302–11.

Benfante A, Di Tella M, Romeo A, Castelli L. Traumatic stress in healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic: a review of the immediate impact. Front Psychol. 2020;11:569935.

De Wijin GN, van der Doef MP. Patient-related stressful situations and stress- related outcomes in emergency nurses: a cross-sectional study on the role of work factors and recovery during leisure time. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;107:103579.

Lasalvia A, Bodini L, Amaddeo F, Porru S, Carta A, Poli R, et al. The sustained psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers one year after the outbreak – a repeated cross-sectional survey in a teritary hospital of north-east Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:13374.

Imai H, Matsuishi K, Ito A, Mouri K, Kitamura N, Akimoto K, et al. Factors associated with motivation and hesitation to work among health professionals during a public crisis: a cross sectional study of hospital workers in Japan during the pandemic (H1N1) 2009. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:672.

Matsuishi K, Kawazoe A, Imai H, Ito A, Mouri K, Kitamura N, et al. Psychological impact of the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 on general hospital workers in Kobe. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;66:353–60.

Weiss DS. The impact of event scale: revised. In: Wilson JP, Tang CS, editors. Cross-cultural assessment of psychological trauma and PTSD. Boston: Springer; 2007. pp. 219–38.

Asukai N, Kato H, Kawamura N, Kim Y, Yamamoto K, Kishimoto J, et al. Reliability and validity of the japanese-language version of the impact of event scale-revised (IES-R-J): four studies of different traumatic events. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190:175–82.

Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP, Maslach C. Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Dev Int. 2009;14:204–20.

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach burnout inventory manual. 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996.

Leiter MP, Schaufeli WB. Consistency of the burnout construct across occupations. Anxiety Stress & Coping. 1996;9:229–43.

Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Schaufeli WB. Validation of the Maslach Burnout Inventory – General Survey: an internet study. Anxiety Stress & Coping. 2002;15:245–60.

O’Connor K, Muller Neff D, Pitman S. Burnout in mental health professionals: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and determinants. Eur Psychiatry. 2018;53:74–99.

Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, Rosales RC, Guille C, Sen S, et al. Prevalence of burnout among physicians: a systematic review. JAMA. 2018;320:1131–50.

Kitaoka K, Masuda S. Academic report on burnout among japanese nurses. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2013;10:273–9.

Kitaoka K, Masuda S, Ogino K, Nakagawa H. The Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS) and the japanese version. Hokuriku J Public Health. 2011;37:34–40. (in Japanese).

Kitaoka-Higashiguchi K, Nakagawa H, Morikawa Y, Ishizaki M, Miura K, Naruse Y, et al. Construct validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey. Stress Health. 2004;20:255–60.

Kitaoka-Higashiguch K, Ogino K, Masuda S. Validation of a japanese research version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey. Shinrigaku Kenkyu. 2004;75:415–9. (in Japanese).

Matsuo T, Kobayashi D, Taki F, Sakamoto F, Uehara Y, Mori N, et al. Prevalence of health care worker burnout during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Japan. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2017271.

Kalimo R, Pahkin K, Mutanen P, Topipinen-Tanner S. Staying well or burning out at work: work characteristics and personal resources as long-term predictors. Work Stress. 2003;17:109–22.

Matsuo T, Taki F, Kobayashi D, Jinta T, Suzuki C, Ayabe A, et al. Health care worker burnout after the first wave of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Japan. J Occup Health. 2021;63:e12247.

Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e203976.

Badahdah A, Khamis F, Mahyijari NA, Balushi MA, Hatmi HA, Salmi IA, et al. The mental health of health care workers in Oman during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2021;67:90–5.

Elbay RY, Kurtulmuş A, Arpacıoğlu S, Karadere E. Depression, anxiety, stress levels of physicians and associated factors in COVID-19 pandemics. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113130.

Dosil Santamaría M, Ozamiz-Etxebarria N, Redondo Rodríguez I, Jaureguizar Alboniga-Mayor J, Picaza Gorrotxategi M. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on a sample of spanish health professionals. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Engl Ed). 2021;14:106–12.

Kang L, Ma S, Chen M, Yang J, Wang Y, Li R, et al. Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: a cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:11–7.

Corbett GA, Milne SJ, Mohan S, Reagu S, Farrell T, Lindow SW, et al. Anxiety and depression scores in maternity healthcare workers during the Covid-19 pandemic. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020;151:297–8.

Yildirim TT, Atas O, Asafov A, Yildirim K, Balibey H. Psychological status of healthcare workers during the Covid-19 pandemic. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2020;30:26–31.

Serrano-Ripoll MJ, Meneses-Echavez JF, Ricci-Cabello I, Fraile-Navarro D, Fiol-deRoque MA, Pastor-Moreno G, et al. Impact of viral epidemic outbreaks on mental health of healthcare workers: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:347–57.

Sim K, Chong PN, Chan YH, Soon WS. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related psychiatric and posttraumatic morbidities and coping responses in medical staff within a primary health care setting in Singapore. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1120–7.

Su TP, Lien TC, Yang CY, Su YL, Wang JH, Tsai SL, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity and psychological adaptation of the nurses in a structured SARS caring unit during outbreak: a prospective and periodic assessment study in Taiwan. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:119–30.

Galanis P, Vraka I, Fragkou D, Bilali A, Kaitelidou D. Nurses’ burnout and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77:3286–302.

Maunder R. The experience of the 2003 SARS outbreak as a traumatic stress among frontline healthcare workers in Toronto: Lessons learned. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359:1117–25.

Nickell LA, Crighton EJ, Tracy CS, Al-Enazy H, Bolaji Y, Hanjrah S, et al. Psychosocial effects of SARS on hospital staff: survey of a large tertiary care institution. CMAJ. 2004;170:793–8.

Lasalvia A, Amaddeo F, Porru S, Carta A, Tardivo S, Bovo C, et al. Levels of burn-out among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic and their associated factors: a cross-sectional study in a tertiary hospital of a highly burned area of north-east Italy. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e045127.

Han L, Wong FKY, She DLM, Li SY, Yang YF, Jiang MY, et al. Anxiety and depression of nurses in a north west province in China during the period of novel coronavirus pneumonia outbreak. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2020;52:564–73.

Wang H, Liu Y, Hu K, Zhang M, Du M, Huang H, et al. Healthcare workers’ stress when caring for COVID-19 patients: an altruistic perspective. Nurs Ethics. 2020;27:1490–500.

Luceño-Moreno L, Talavera-Velasco B, García-Albuerne Y, Martín-García J. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, depression, levels of resilience and burnout in spanish health personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:5514.

Barello S, Palamenghi L, Graffigna G. Burnout and somatic symptoms among frontline healthcare professionals at the peak of the italian COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113129.

Wu Y, Wang J, Luo C, Hu S, Lin Xi, Anderson AE, et al. A comparison of burnout frequency among oncology physicians and nurses working on the frontline and usual wards during the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2020;60:e60–5.

Tam CWC, Pang EPF, Lam LCW, Chiu HFK. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Hong Kong in 2003: stress and psychological impact among frontline healthcare workers. Psychol Med. 2004;34:1197–204.

Song X, Fu W, Liu X, Luo Z, Wang R, Zhou N, et al. Mental health status of medical staff in emergency departments during the coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:60–5.

Khatatbeh M, Alhalaiqa F, Khasawneh A, Al-Tammemi AB, Khatatbeh H, Alhassoun S, et al. The experiences of nurses and physicians caring for COVID-19 patients: findings from an exploratory phenomenological study in a high case-load country. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:9002.

Ide K, Asami T, Suda A, Yoshimi A, Fujita J, Nomoto M, et al. The psychological effects of COVID-19 on hospital workers at the beginning of the outbreak with a large disease cluster on the Diamond Princess cruise ship. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0245294.

Peng M, Mo B, Liu Y, Xu M, Song X, Liu L, et al. Prevalence, risk factors and clinical correlates of depression in quarantined population during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:119–24.

Meredith LS, Bouskill K, Chang J, Larkin J, Motala A, Hempel S. Predictors of burnout among US healthcare providers: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054243.

Acknowledgements

We thank the hospital staff of Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital for their assistance in this study.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HF, HI, CM, AN, KO, and KM were involved in the study design. HI and CM contributed to the data analysis. HF, AN, KO, and KM contributed to the acquisition of data. HF drafted the initial manuscript, which was then revised by HI, CM, and KM. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital (no. zn220903). Written informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Fukushima, H., Imai, H., Miyakoshi, C. et al. The sustained psychological impact of coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on hospital workers 2 years after the outbreak: a repeated cross-sectional study in Kobe. BMC Psychiatry 23, 313 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04788-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04788-8