Abstract

In the Republic of Benin, mangroves are an essential resource for the coastal populations who use them for firewood, salt production, and ruminant feeding. However, little information exists on livestock keepers’ particular threats to mangroves. This study aims to understand the use of mangrove species by ruminant keepers to identify sustainable actions for mangroves conservation in the coastal area of Benin. Ethno-botanical and socio-economical surveys were conducted on ninety (90) ruminant farmers in fifteen (15) villages close to mangroves along the coastal belt using a semi-structured questionnaire. The herders provide their animals with different mangrove plant species for feeding and health care. Rhizophora racemosa, Avicennia africana, Paspalum vaginatum, Zanthoxylum zanthoxyloides and Blutaparon vermiculare were the primary species used for ruminants. Local communities of herders were aware of the need to restore and ensure the sustainable use of mangrove ecosystems. The main restoration and conservation strategy suggested was planting the true mangroves plant species. Others strategies were rational use of mangroves resources and avoiding burning mangroves. These strategies varied with the ethnical group of the herder and the mangrove status (degraded or restoring) in their location. The study also revealed the willingness of ruminant breeders to participate in actions to conserve mangroves. This participation in mangrove restoration was influenced by the ethnical group and age of the herder. Therefore, it is important to involve more ruminant farmers in activities and projects for mangroves restoration. Further study could evaluate whether grazing could enhance the other ecosystem services of mangroves.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

1.1 Background

Worldwide, mangroves are considered a highly vulnerable ecosystem [1]. Mangroves are mainly located between freshwater and saline water environments [2, 3], and covered up to 16.4 million ha in 2014 [4]. They provide valuable ecosystem services such as carbon sequestration, coastal barriers, shoreline protection, food, fuel, building materials, and biodiversity protection [5,6,7,8]. However, mangroves are one of the most threatened habitats.

About 35% of the world’s mangroves have been lost for several reasons [9]. Mangroves are degraded in many areas due to climate change [10, 11] and to human activities [12, 13], mainly urban development in the coastal areas [14, 15] and overexploitation of resources [16]. These threats call for various actions for sustainable management and conservation of mangroves [17]. Accurate estimation of the mangrove forest cover change rate could correctly inform conservation policymakers to reduce functional losses [12, 18].

Overharvesting of mangroves species is one of the significant threats to mangrove forests [13]. Livestock keepers also use mangroves to feed their animals, particularly ruminants, in many countries, including Benin, Senegal, New Zealand, Indonesia, and Pakistan [1, 13, 19,20,21,22].

Livestock contributes, on average 13% to the GDP (Gross Domestic Product) of the Republic of Benin [23]. Ruminants grazed in mangroves forests and swamps, and leaves of Rhizophora racemosa and Paspalum vaginatum were harvested and sold or preserved as fodder for the dry season [24]. However, no information exists on the amount of the different foliage harvested and how the different parts of the true mangrove species are used for ruminants. This information is important in conservation decision-making and valuation of these mangrove services [25].

Most of the study conducted in Benin has focused on mangrove interests for human populations, particularly medicinal, food, and other uses for human well-being [13, 26,27,28]. Some authors had investigated the floristic and faunal inventory of mangrove ecosystems [29] and some conservation issues [15]. According to Zanvo et al. [30], from 2001 to 2019, mangroves had changed to grasslands (7.25%) or another vegetation type (27.05%), with higher degradation in the municipalities of Abomey-Calavi and Ouidah. Therefore, there are various actions for the sustainable conservation of mangroves by several NGOs and projects through the Mono Transboundary Biosphere Reserve (Togo and Benin) and RAMSAR convention along the coastal belt of Benin [12, 13]. However, none of these participatory actions specifically consider livestock keepers as contributors to the threats to this resource.

1.2 Assumption and objectives

This study aims to (i) assess the use patterns of mangroves’ true species by livestock farmers for their ruminant herds, (ii) understand herders’ perception of the threats to mangrove forests, and (iii) identify with the herder’s participatory actions for mangroves restoration and conservation. We hypothesize that the ethnical origin of the respondents affects their contribution to enhancing mangrove management and conservation actions in the coastal areas of Benin.

2 Methods

2.1 Study area

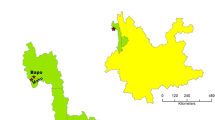

The study area is the coastal belt of the Republic of Benin located between 1°44′30″ and 2°37’00 East longitude and between 6°15′50″ and 6°44’85’’ of North latitude. This study was conducted in four municipalities (Sèmè-Podji, Abomey-Calavi, Ouidah and Grand Popo) along the coastal area of Benin. The municipality of Cotonou was not investigated because of the absence of mangroves in this urban area (Fig. 1). The climate in the study area is a subequatorial type with two rainy seasons, from April to July and mid-September to October; and two dry seasons, from December to March and mid-August to mid-September. The annual rainfall is between 820 and 1300 mm, with a temperature of 25–27.7 °C. Soils are sandy, hydromorphic, and ferralitic types. Though very diverse, the plant communities in the coastal zone are dominated by two true mangroves species; Rhizophora racemosa and Avicennia africana [29]. Other species of the mangrove swamp included Drepanocarpus lunatus, Dalbergiae castaphyllum, Laguncularia racemoa, Thespesia populnea, Annona senegalensis, Bridelia ferruginea, Imperata cylindrica, Sesuvium postulacastrum, Phyloxesus vermicularias, and Acrostichum aureum [27]. The population of the coastal area of Benin is of different ethnical groups, including Fôn, Mina, Houeda and Xwla. The economic activities practiced are agriculture, fishery, livestock rearing, salt production, trading, marine sand exploitation, and hunting [15].

2.2 Sampling and data collection

An ethnobotanical survey was conducted in the surrounding villages of the forth (4) studied municipalities. Ruminant herders were interviewed in fifteen (15) villages close to the mangrove swamps. Those villages were chosen regarding the existence of ruminant herders that use mangrove swamps and the presence of other socio-professional groups using the mangroves, such as traditional healers, fishermen, and women who specialized in salt production.

The target group for this study included fifteen cattle herders and seventy-five sheep and goat herders. Therefore, ninety (90) breeders were randomly selected and interviewed individually. The snowball sampling method as described by [14] and [31] was used for the herders selection. Supplementary data was collected through field visits and group discussions. The field visit was implemented as described by [32] and permitted to identify the plant species elicited by the herders during the survey. The herders were asked to provide local names of the mangrove plant species used as feedstuffs and medicine, the diseases or disorders treated with them, and the plant organs used. They were also asked to indicate the ruminant type using the mentioned plant parts. Vouchers were produced, and the scientific names of the different plants identified by experts at the National Herbarium of Benin.

Data was also collected on the farm’s socioeconomic characteristics, the herd composition, and the ruminant feeding management in communal grasslands, including mangrove forests. The discussions with those farmers and the local authorities confirmed that mangroves were degraded along the coastal belt of Benin.

Several projects were implemented to conserve biodiversity and sustainable use of mangrove resources through the Ramsar Convention [12]. However, the current trend of mangrove ecosystem is either still degraded (named: “Degraded”) or in restoration (named: “Restoring”). Through the survey, farmers were asked to give an evaluation of the importance of mangrove resources for their animals. Moreover, questions related to the actual conservation status of mangroves (degraded or restoring), farmers perceived threats, and strategies for sustainable management of mangroves were discussed.

2.3 Data analysis

Ethnobotanical indices were calculated based on the popularity and versatility of species (woody and herbaceous species). The relative frequency of citation (RFC), as described by Tardio and Pardo-de-Santayana [33], was used to assess the importance of each species through the use categories. The RFC value is obtained by dividing the number of breeders who mention a given species used by the number of participants in the study.

The Use Value (UV) of each species was calculated for each ethnical group using Phillips and Gentry [34] method, simplified by Rossato [35] as follows:

where Ui represents the number of uses mentioned by a breeder i and N represent the total number of herders interviewed.

This index was then used to perform a correspondence analysis to compare mangrove species use between ethnical groups. The R version 3.6.0. package FactoMineR [36] was used for this analysis.

The ruminant production system was characterized in relation to the conservation status of mangroves. Cross-tabulations with the calculation of chi-square statistics were used to compare qualitative characteristics of the farms according to the perceived mangroves characteristics. Means and standard deviation values were calculated for the continuous variables, and comparisons were made using the non-parametric test of Kruskal-Wallis W.

Mangroves conservation strategies proposed by the surveyed farmers were compared between ethnical groups and mangroves status, using cross-tabulations with chi-square statistics. Then, a stepwise logistic regression analysis using the backward procedure was carried out to identify the socio-economic factors that affect the choice of a given conservation strategy (1: restoring or 2: others). All the statistical analysis were performed in R version 3.6.0 [37].

3 Results

3.1 Ethnobotanical knowledge of ruminant herders on mangrove plants utilization

3.1.1 Socio-economic characteristics of the surveyed ruminant farmers

In the coastal belt of Benin, ruminant farming is practiced by men and women. Cattle farmers were 43.2 ± 17.29 years old, while the average age of the small ruminant farmers was 51.04 ± 16.02 years. The cattle herders belonged to the Fulani socio-cultural group from Niger and Northern Benin (Natitingou, Savè, Malanville, and Karimama). Cattle farming was their main activity, and they have been using mangrove swamps for 19.93 ± 16.62 years.

The small ruminant farmers were Beninese and kept sheep and/or goats in the area for 14.71 ± 11.58 years. Most of them was using mangrove for 21.65 ± 13.53 years. The latter practiced animal husbandry as a secondary activity. In contrast to the cattle keeper group, their other activity related to the use of the mangrove was fishing and traditional medicine by men, while women practiced salt production. They were all autochthon and belonged to the Xwla, Peda, Fon ethnical groups and other groups (Yoruba, Goun, Evé, and Nago).

Three ruminant farming systems have been identified in the area, including family small ruminant farming (81.11%), entrusted cattle farming (13.33%), and mixed cattle-coconut farming (5.56%). Family farms owned sheep and goats (5.59 heads) that were reared and kept in paddocks or at the homestead. In entrusted farms, cattle herd size is 42.20 heads/herd, and 101.40 heads were kept under coconut trees. The cattle breeds were Bobodji, Yakana, Borgou and Djabadjaba breeds. Small ruminant breeds used were Djallonké and Sahelian.

3.1.2 Ruminant herders’ perception of pastoral importance of the mangrove species

Five plant species were used in ruminant keeping, including two true mangroves species Rhizophora racemosa and Avicennia africana, and three species from the swamp, such as Zanthoxyllum zanthoxyloides, Blutaparon vermiculare and Paspalum vaginatum. For each species, the plant parts used, the ruminant type fed, and the location of the farmers’ were documented (Table 1). Rhizophora racemosa, Avicennia africana and Zanthoxyllum zanthoxyloides leaves were harvested to feed the animals, whereas Blutaparon vermiculare and Paspalum vaginatum were grazed.

According to the herders, all the organs of R. racemosa and A. africana were used for small ruminants (sheep and goats).

Mangrove species were mentioned in four (04) use categories: feeding, health, fold building, and reproduction management. However, the number of use categories varied among species, as showed in Table 2.

All the species elicited were used for animal feeding, mainly R. racemosa (55.6%), P. vaginatum (64.44%) and A. africana (27.78%). In particular, the different parts of the true mangroves species R. racemosa and A. africana, were diversely used in animal feeding (Fig. 2). Leaves (55.55% and 27.77% for R. racemosa and A. africana, respectively) and bark (35.55% and 16.66% R. racemosa and A. africana, respectively) were most parts ingested by small ruminants. Also, flowers and young stalks from R. racemosa and wood of A. africana were well used.

Moreover, R. racemosa was mentioned in all the use categories. The wood was used for fold building (5.56%) and its leaves and bark in reproduction management (1.11%). Z. Zanthoxyloides (21.11%) leaves were used against diarrhea and skin diseases for animal health.

The correspondence analysis (Fig. 3) showed that the first two axes explained more than 93% of the total variation (axis 1 = 67.92% and axis 2 = 25.42%). Only these axes were used to describe the relationship between ethnical groups and mangroves plant species utilization in ruminant keeping.

Considering axis 1, R. racemosa, B. vermiculare and A. africana constituted the primary plants used by local ethnical groups Xwla and Pedah, while P. vaginatum was the only species used by Fon and Fulani ethnical group. On axis 2, others ethnic groups such as Goun, Nagot, Evé and Yoruba preferred Z. zanthoxyloides.

3.2 Ruminants production around mangroves forests

All the herders interviewed perceived some changes in mangroves. Instead of restoration efforts by the Beninese Government and NGOs, 42.2% of the herders mentioned that the mangroves forests were still degraded (“Degraded”). In comparison, the others (57.8% of herders) perceived a positive restoration trend (“restoring”).

3.2.1 Socio-economic characteristics of farms around degraded or restoring mangroves

Tables 3 and 4 showed the socio-economic characteristics of ruminant farms around degraded and restoring mangroves. The level of formal education of the herder, his ethnic group and religion, the use of mangrove resources, and the main ruminant kept varied significantly (P < 0.001) according to the status of the mangrove (degraded or restoring).

Degraded mangroves were mainly located in Sèmè-Podji (31.8%) and Abomey-Calavi (28.9%). Half of the farmers around those mangroves attended school and were from the Fulani (23.7%), Fon (21.1%), or other ethnic groups (15.8%). They were even Christian (31.6%) or Muslim (26.3%). Farmers around degraded mangroves raised more cattle (26.3%) than restoring mangroves. Most (73.7%) of the farmers of this group also kept small ruminants. On average, only one mangrove tree or related species was used for animal feeding. Most (52.6%) of them mentioned this species to be used as alternative forage.

The group “Restoring” was mainly located in Ouidah (57.7%) and Grand-popo (42.3%). Half of them attend elementary school (55.8%), and they belong to Xwla (61.5%) and Peda (19.2%) autochthon ethnical groups. They practice traditional religion (71.2%) and kept small ruminants (90.4%) with a larger (P < 0.01) size of sheep herd (9.36 heads/herd) than in the group “Degraded”. Mangroves and related species used to feed these animals were significantly higher (P < 0.05) with 2.02 species, and these species were used by 71.2% of the herders as forage. Also, a higher proportion (20%) of the oldest farmers (≥ 60 years old) was found in this group.

3.2.2 Herders’ perceptions of the threats to mangroves and conservation strategies

The main threats of mangrove forest degradation were due to uncontrolled cutting/harvesting (57.82%), the use of mangrove species for firewood and salt production (26.30%), and human settlements (2.61%). Half (47.39%) of the herders acknowledged their dependence on mangrove forests and surrounding grasslands for their ruminant herd. Those farmers realized that the full degradation of mangroves could hinder their livestock-keeping activity.

However, no threats were mentioned regarding ruminant grazing around or into mangrove swamps. Nonetheless, ruminant herders suggested some strategies for the sustainable conservation of mangroves (Fig. 4). These strategies varied significantly (P ≤ 0.001) between small ruminants and cattle herders. Most small ruminants’ owners suggested mangroves trees planting (42.7%) and cutting control (32%), while cattle owners emphasized better management of conflicts between farmer-breeder (33.3%). Both cattle and small ruminant herders also proposed participatory management of the resource.

Figure 5 showed that close to “Degraded” mangroves, the strategies most used by farmers are planting true mangroves species (52.61%) and rational use of resources by controlling cutting (18.48%). Around “Restoring” mangroves, the most proposed conservation strategies were the rational exploitation through the control of cutting and better management (38.41%), mangrove planting (28.89%) or participatory management (15.40%).

The farmer’s conservation strategies according to ethnic groups (Fig. 6) showed that the local ethnical groups Xwla (20%) and Peda (4.4%) were the most involved in the conservation or restoration of mangrove ecosystems through planting (40% for Xwla, 33.33% for Peda) and rational exploitation by controlling cutting (33.33 for Xwla, 41.67 for Peda). The Fulani and Fon ethnic groups, apart from mangrove planting and their rational management, had suggested participatory management and the planting of other species. The Fulani people further indicated the promotion of good governance of conflicts between farmers and herders.

3.2.3 Farmers’ future strategies for sustainable conservation of mangrove forests

The herders surveyed have mentioned their willingness to participate in actions to restore and conserve degraded mangrove ecosystems in southern Benin. Most of them agree with planting the mangroves like R. racemosa and A. africana, and suggested finding alternatives firewood/energy. They had also suggested developing a participatory approach with different stakeholders to restore and effectively conserve mangrove ecosystems in southern Benin.

The results of the logistic regression analysis are presented in Table 5. The analysis used the socio-economics characteristics of the farmers that were likely to influence their willingness to participate in the mangrove conservation strategy. The herders’ age, education level, ethnic group, farm location, religion, and herders types (cattle or small ruminants’ keepers) were selected as predictors. Variables highly correlated with the others like education level, religion and herder types were removed from the predictors’ list.

Using the remaining variable, the backward logistic regression permits retaining the age of the herders and his ethnical group as suitable to predict farmers’ willingness to contribute to enhancing mangrove restoration and conservation. Indeed, the full model was statistically significant, indicating that the predictors (age and ethnic group) as a whole reliably distinguish farmers’ that contribute to mangrove restoration and the others (df = 6, χ2 = 24,470, P < 0,001). The Nagelkerke R2 value of 0.320 indicates a moderately strong relationship between prediction and aggregation. The non-significance of Hosmer and Lemeshow’s test confirmed the validity of the regression model. The success of the prediction was 68.42% for the group of herders who reported degradation and 76.92% for those who contributed to restoration strategy for better conservation of mangrove resources. The eß values indicate that when the herder was an adult (31–59 years old), the odds ratio is 0.130 times as large. This odds ratio is 9.328 and 19.85 times greater when the herders were respectively of Peda or Fulani ethnic groups. These results implied that the probability that a herder contributes to enhancing actions for mangroves conservation increases in adult herders’ farms and farms kept by Fulani and Peda people.

4 Discussion

4.1 Various uses of mangroves by ruminant herders

Our results showed that along the coastal belt of southern Benin, two true mangroves species (Avicennia africana; Rhizophora racemosa) and three associated species were the most used in ruminant rearing, following findings of [22]. Those species were the most abundant in the area [26]; however, more species were mentioned in Grand-popo where mangroves had been acknowledged as less degraded [13]. In addition, mangrove resources have been diversely used for various purposes by local communities [15].

Grazing in wetlands, including mangroves, was the major feeding strategy [14] along the coastal belt of Benin during dry seasons. Therefore, animals rely on dominant herbaceous in mangrove swamp species like P. vaginatum and B. vermiculare, while true mangroves species A. germinans and R. racemosa were harvested and supplemented. Both true species had also been acknowledged as the most used in animal feeding in Indonesia by Zuhri et al. [22]. Moreover, leaves of Z. zanthoxyloides that are also available in the area were harvested to supplement the animals.

The mangroves species were differently used by ethnical groups, suggesting high pressure by authochton ethnical groups Xwla and Peda. All the plant parts of the two true woody species were used. In addition to feeding, the use as wood [13] or medicine [22, 38] was acknowledged. However, R. racemosa bark was cited in reproduction management in sheep farms, which is less known in the literature. Indeed, this species is fed to sheep to obtain more male than female offspring. The latter use could be justified by the presence of sheep fattening units in the periurban area of Cotonou, as found by [39] in west-African cities, increasing the need for male offspring. In addition, Gnansounou et al. [13] argue that the species is highly palatable to goats. Among other uses reported in the literature, goats graze on fallen leaves and propagules of the mangroves of the genus Rhizophora sp. [22]. The same trend was observed Ouidah region, where small ruminants fed on the fallen leaves of R. racemosa and A. africana.

The surveyed small ruminant farmers used the anthelminthic properties of Zanthoxylum zanthoxyloides leaves, according to findings by Vinoh et al. [38]. R. racemosa (names Xwèto) appeared to be the most helpful to local ethnical groups. Farmers mainly used (A) africana in Ouidah and Grand Popo municipalities, where this plant was named Akpontin by Xwla and Peda. (B) vermiculare was only found in Ouidah and named Djèdjè by Xwla and Peda people, the predominant ethnical groups in this area.

Some other species of mangroves plants, such as Laguncularia racemosa and Conocarpus erectus, which were also found in these forests, were not used by the herders. However, some other studies [40] showed the feeding use of Avicennia marina, a true mangrove species in the Indian region. It was reported that Avicennia sp. is good fodder for small ruminants [21, 22, 41] with high crude protein (13% DM) and palatability, justifying its preference for supplementing small ruminants in our study.

However, true mangrove species were less used for cattle among the studied farmers in southern Benin. Fulani people that were cattle herders did not have a broad knowledge of mangrove resources like the autochthon ethnical groups’ of the area. At the same time, Fulani people had been known to have the capacity to identify the greatest number of useful forest species [31]. Their low interest in true mangroves species could be explained by the low fodder availability to be harvested for their large herd. Indeed, using mangrove swamp for grazing is an alternative to forage shortage in other areas of the coastal zone [14].

4.2 Mangroves degradation drivers

Mangrove’s degradation was mainly due to human activities, as found in previous studies [13]. Uncontrolled exploitation for several uses, including salt production and firewood needs, was commonly elicited, corroborating the literature’s results [15, 40]. Worldwide, many mangrove forests experienced similar threats and conversion to other land uses such as agriculture and aquaculture [42]. As found in our study, frequent grazing by cattle and fodder collecting for feeding small ruminants could disrupt the normal functioning of this ecosystem [12]. Mainly ruminant herders mentioned degradation as a consequence of uncontrolled harvesting. Stewart and Fairfull [43] and Baba et al. [44] reported that uncontrolled access of livestock, especially cattle and camels, to mangroves could induce considerable damage by killing the young seedlings and stunting the growth of trees and shrubs or could destroy root systems or pneumatophores by trampling.

In India and South Africa, Hope-speer and Adams [45] linked slower and stunted growth of mangroves and lower frequency of flowering and fruiting to grazing pressure by camels, and fodder harvesting for cattle. This situation may be enhanced by the accessibility of the mangrove sites and the high preference for leaves of mangrove trees by those animals [44]. As suggested by [44], herders are expected to regulate the animals’ access to mangroves, to reduce the treats in mangrove forests.

The low forage availability in the periurban area during the dry season could explain the pressure on mangroves by ruminants in southern-Benin [14]; therefore, ruminants rely on mangroves located close to the city. With increased in ruminant keeping and the commercial gardening in this area, pressures on mangroves will also rise over the years. Thus, ruminant husbandry around mangroves should be improved and maintained through management options such as reducing the average herd size, better animal and crop integration, fodder cultivation, and sustainable management of the remaining grazing areas.

4.3 Determinants of ruminant keepers’ participation in restoration and conservation of mangroves

Wetlands utilization for feeding animals is a well-known strategy for coping with forage scarcity during dry seasons [14]. The ruminant production system around mangrove swamps described in our study calls for the strong relationship between land use and animals and justify the need to involve ruminant breeder in the sustainable management of mangroves. Therefore, ruminant herders are expected to participate in the sustainable management of these resources.

Mangroves were restored in areas with educated farmers of local communities (Xwla and Peda) that use more than two mangroves species. As most of them attend school, those farmers were expected to understand the needs and actions for sustainable conservation of mangroves. In addition, these local populations practicing other occupations linked to mangroves like fishing and salt production were much more dependent on mangroves. Therefore they contribute to the conservation and sustainable management of this resource. The importance of traditional religion in natural resources conservation, as mentioned in previous studies [46] was evident in southern-Benin. Indeed, most farmers around restored mangroves practice traditional religion.

On the other hand, farmers perceived continuous degradation of mangroves in Semè-Podji, the most urbanized communes beside Cotonou. Most herders had no formal education and no other activities linked to mangroves, which could reduce their interest and awareness to conserve this resource. Our results showed a difference in the status of mangrove resources according to ethnical group and age herders’, which was consistent with findings in the literature [47,48,49,50]. Xwla and Fulani were the dominant ethnic groups around degraded mangroves, which justifies the state of the mangrove because of cattle rearing on mangrove swamp and fishing activities that require the cutting of mangrove plant woods.

NGOs implemented several many projects for the sustainable conservation of mangroves in Benin [12]. However, these actions hardly concern ruminant keepers as contributors to threats on mangrove resources. Our study showed that the age and the ethnical group of a herder were the factors that influenced his decision to participate in actions for mangroves’ restoration. Both factors were widely identified as determinants of sustainable agricultural practices adoption [51]. Teka et al. [19] highlighted the link between ethnical groups, natural resource uses, and the willingness to participate in this resource conservation. Therefore, mangroves conservation strategies should consider paying attention to age and ethnical group of herders to be involved in conservation actions.

4.4 Prospects for mangrove conservation

The studied farmers reported the need for their animals to graze in mangroves during dry seasons to sustain ruminant production in the area. In this area, urbanization and cultivated land extension had reduced grazing lands, while climate change increased the farmers’ vulnerability [11]. All the coastal area herders were aware of the importance of these ecosystems for them and of their degradation. They had all mentioned their willingness to contribute to mangrove conservation by rationally using the resource and planting the true mangrove species. The latter actions were ongoing in the area; however, cattle herders suggested improving land-use patterns to avoid the recurrent conflict they experienced with crop farmers. As a result, grazing lands availability could be increased, and cattle could avoid grazing in mangroves if more grazing areas were available. Xwla and Fulani people also suggested planting true mangrove trees, while Peda preferred controlling harvesting and rational use of mangroves resources.

Instead of the several projects implemented in the Ramsar site in 2017 and the Mono Transboundary Biosphere Reserve (Togo-Benin) for mangroves conservation, not everywhere restoration occurred. The suggested strategies by farmers also varied between the two mangroves’ status (degraded or restoring). Near the still degraded mangroves, the strategies most used by farmers were planting mangroves and rational use through controlled cuts. On the other hand, near mangroves in restoration, the most used conservation strategies were mainly rational exploitation through control of cutting and management. Thus, livestock herders should be more involved in actions for the sustainable management of mangroves. Participatory co-management of mangroves remains the most acceptable strategy [52] at the level of sites under restoration, while planting could be suggested at degraded sites [15]. As indicated by [15], the restoration of traditional rules could also enhance actions for the conservation of mangroves.

The burning of stumps after cutting is frequent and could reduce the regeneration of the species. Therefore, stopping this threat and planting the true mangroves and other trees could be an alternative to reduce the pressure on this particular ecosystem. Indeed, informants had suggested planting other trees than the mangrove true ones, which could be used as an alternative for providing fuel and forage. Therefore, the cultivation of fodder species like Gliricidia sepium, Leucaena leucocephala and Acacia sp. to be used as forage for the ruminants [53] could be helpful to avoid pressure on mangroves. This is a possible new strategy for saving mangrove ecosystems from degradation in southern Benin.

To ensure the sustainability of mangrove management in the coastal areas of Benin, collective actions and supports for the establishment of policies and institutions are necessary [54]. To this end, there is an urgent need to prioritize the integration of socio-economic factors while improving local people’s livelihoods with other income-generating activities. Thus, the implementation of the following actions could contribute to the conservation of mangrove ecosystems : (1) planting of true mangrove species; (2) sensitization and training of herders for the establishment of fodder crops; (3) promotion of fast-growing species to support the demand for timber and fuelwood; (4) promotion of better land-use pattern with more grazing lands; (5) contribution to food security and poverty alleviation by improving animal productivities (genetic potential, better feeding, and secure watering).

5 Conclusion

This study helped to understand the use of mangrove ecosystems by ruminant breeders and their contribution to its degradation and potential restoration in Benin (West Africa). Five (05) species of mangroves, namely Rhizophora racemosa, Avicennia africana, Paspalum vaginatum, Zanthoxylum zanthoxyloides and Blutaparon vermiculare were used in ruminant rearing. Among the categories of use, ruminant feeding was the most cited. The use of these resources varied according to ethnical groups. Native herders were much more interested in the organs of the true mangrove trees, Rhizophora racemosa and Avicennia africana, for their small ruminants herds. However, migrant cattle herds grazed in the surrounding grasslands during the dry season. At the same time, other activities are carried out in the mangroves, such as salt preparation, fishing, and harvesting wood for fuel services and human settlements. All these threats affect the sustainability of mangrove ecosystems, mainly in areas close to the cities. Our study revealed that ethnical group appurtenance and the age of herders influenced the management of mangroves. Livestock breeders in the coastal zone suggested conservation strategies through mangrove planting, controlled cutting, and participatory governance, which could ensure this ecosystem preservation and conservation.

Data availability

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the paper and its additional files.

Abbreviations

- FAO:

-

Food and Agriculture Organization

- RFC:

-

Relative frequency of citation

- UV:

-

Use value

- AFC:

-

Correspondence factor analysis

References

Rafique MA. Review on the status, ecological importance, vulnerabilities, and conservation strategies for the mangrove ecosystems of Pakistan. Pak J Bot. 2018;50(4):1645–59.

Giri C, Ochieng E, Tieszin LL, Zhu Z, Singh A, Loveland T, Masek J, Duke N. Status and distribution of mangrove forests of the world using earth observation satellite data. Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2011;20:154–9.

Giri C, Long J, Abbas S, Murali RM, Qamer FM, Pengra B, Thau D. Distribution and dynamics of mangrove forests of South Asia. J Environ Manag. 2015;148:101–11.

Stuart EH, Casey D. Creation of a high spatio-temporal resolution global database of continuous mangrove forest cover for the 21st century (CGMFC-21). Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2016;25:729–38.

Estoque RC, Myint SW, Wang C, Ishtiaque A, Aung TT, Emerton L, Ooba M, Hijioka Y, Mon MS, Wang Z, Fan C. Assessing environmental impacts and change in Myanmar’s mangrove ecosystem service value due to deforestation (2000–2014). Glob Chang Biol. 2018;24:5391–410.

Himes-Cornell A, Pendleton L, Atiyah P. Valuing ecosystem services from blue forests: a systematic review of the valuation of salt marshes, sea grass beds and mangrove forests. Ecosyst Serv. 2018;30:36–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2018.01.006.

Himes-Cornell A, Grose SO, Pendleton L. Mangrove ecosystem service values and methodological approaches to valuation: where do we stand? Front Mar Sci. 2018. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2018.00376.

Reyes-Arroyo N, Camacho-Valdez V, Saenz-Arroyo A, Infante-Mata D. Socio-cultural analysis of ecosystem services provided by mangroves in La Encrucijada Biosphere Reserve, southeastern Mexico. Local Environ. 2021;26(1):86–109.

Polidoro BA, Carpenter KE, Collins L, Duke NC, Ellison AM, Ellison JC, et al. The loss of species: mangrove extinction risk and geographic areas of global concern. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(4):e10095.

Boateng I. An assessment of vulnerability and adaptation of coastal mangroves of West Africa in the face of climate change. In: Threats to mangrove forests. Cham: Springer; 2018. p. 141–54.

Sinsin CBL, Salako KV, Fandohan AB, Kouassi KE, Sinsin BA, Glèlè-Kakaï R. Potential climate change induced modifications in mangrove ecosystems: a case study in Benin, West Africa. Environ Dev Sustain. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01639-y.

Padonou EA, Gbaï NI, Kolawolé MA, Idohou R, Toyi M. How far are mangrove ecosystems in Benin (West Africa) conserved by the Ramsar Convention? Land Use Policy. 2021;108:105583.

Gnansounou SC, Salako KV, Sagoe AA, Mattah PAD, Aheto DW, Glèlè Kakaï R. Mangrove ecosystem services, associated threats and implications for wellbeing in the mono transboundary biosphere reserve (Togo-Benin), West-Africa. Sustainability. 2022;14(4):2438.

Koura BI, Dossa LH, Kassa BD, Houinato MRB. Adaptation of periurban cattle production systems to environmental changes: feeding strategies of herdsmen in Southern Benin. Agroecol Sustain Food Syst. 2015;39(1):83–98.

Teka O, Houessou LH, Djossa BA, Bachmann Y, Oumorou M, Sinsin B. Mangroves in Benin, West Africa: threats, uses and conservation opportunities. Environ Dev Sustain. 2019;21:1153–69.

Carugati L, Gatto B, Rastelli E, et al. Impact of mangrove forests degradation on biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Sci Rep. 2018;8:13298. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-31683-0.

Feka Zebedee N, Morrison I. Managing mangroves for coastal ecosystems change: a decade and beyond of conservation experiences and lessons for and from west-central Africa. J Ecol Nat Environ. 2017;9(6):99–123. https://doi.org/10.5897/JENE2017.0636.

Friess AD, Webb EL. Variability in mangrove change estimates and implications for the assessment of ecosystem service provision. Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12140.

Teka O, Hentschel US, Vogt J, Bähr HP, Hinz S, Sinsin B. Process analysis in the coastal zone of Bénin through remote sensing and socio-economic surveys. Ocean Coast Manag. 2012;67:87–100.

Maxwell GS, Lai C. Avicennia marina foliage as salt enrichment nutrient for New Zealand dairy cattle. ISME GLOMIS Electron J. 2012;10(8):22–4.

Maxwell GS. Gaps in mangrove science. ISME GLOMIS Electron J. 2015;13:21.

Zuhri F, Tafsin MR. Mangrove utilization as sources of ruminant feed in Belawan Secanang Subdistrict, Medan Belawan District. J Sylva Indones. 2022;5(01):1–9.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Benin introduces artificial insemination in cattle, improving animal breeding and nutrition. Rome: FAO; 2017.

Baglo AA. In: Enjeux économiques des strategies de gestion durable des zones humides: cas de la zone située sur le cordon Abomey-Calavi-Degoue sur le littoral béninois. Bénin: Laboratoire d’écologie appliquée, Faculté des Sciences Agronomiques, Université d’Abomey-Calavi; 2005.

Rahman MD, Jiang Y, Kenneth I. Assessing wetland services for improved development decision-making: a case study of mangroves in coastal Bangladesh. Wetl Ecol Manag. 2018;26:563–80.

Adite A, Toko II, Gbankoto A. Fish assemblages in the degraded mangrove ecosystems of the Coastal Zone, Benin, West Africa: implications for ecosystem restoration and resources conservation. J Environ Prot. 2013;4:1461–75.

Dossou-Yovo HO, Vodouhè FG, Sinsin B. Ethnobotanical survey of mangrove plant species used as medicine from Ouidah to Grand-Popo Districts, Southern Benin. Am J Ethnomed. 2017;4(1):8.

Zanvo MS, Salako KV, Gnanglè C, Mensah S, Assogbadjo AE, Glèlè Kakaï R. Impacts of harvesting intensity on tree taxonomic diversity, structural diversity, population structure, and stability in a West African mangrove forest. Wetl Ecol Manag. 2021;29(3):433–50.

Sinsin B, Assogbadjo AE, Tenté B, Yo T, Adanguidi J, Lougbégnon T, Ahouansou S, Sogbohossou E, Padonou E, Agbani P. Inventaire floristique et faunique des écosystèmes de mangroves et des zones humides côtières du Bénin. Rome: (FAO) Food and Agriculture Organization; 2018.

Zanvo MS, Barima YS, Salako KV, Koua KN, Kolawole MA, Assogbadjo AE, Kakaï RG. Mapping spatio-temporal changes in mangroves cover and projection in 2050 of their future state in Benin. Bois For Trop. 2021;350:29–42.

Ahoyo CC, Houehanou TD, Yaoitcha AS, Prinz K, Assogbadjo AE, Adjahossou CS, Hellwig F, Houinato MRB. A quantitative ethnobotanical approach toward biodiversity conservation of useful woody species in Wari-Maro forest reserve (Benin, West Africa). Environ Dev Sustain. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-017-9990-0.

Houéhanou DT, Assogbadjo AE, Chadare FJ, Zanvo S, Sinsin B. Approches méthodologiques synthétisées des études d’ethnobotanique quantitative en Milieu Tropical. Ann Sci Agron. 2016;20:187–205.

Tardío J, Pardo-de-Santayana M. Cultural importance indices: a comparative analysis based on the useful wild plants of Southern Cantabria (Northern Spain). Econ Bot. 2008;62(1):24–39.

Phillips O, Gentry AH. The useful plants of Tambopata, Peru: additional hypothesis testing in quantitative ethnobotany. Econ Bot. 1993;47:33–43.

Rossato SC, Leitaõ Filho H, Begossi A. Ethnobotany of caic¸aras of the Atlantic Forest coast (Brazil). Econ Bot. 1999;53:387–95.

Lê S, Josse J, Husson F. FactoMineR: a package for multivariate analysis. J Stat Softw. 2008;25(1):1–18. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v025.i01.

Core Team R R. A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2019.

Vinoth R, Kumaravel S, Ranganathan R. Therapeutic and traditional uses of mangrove plants. J Drug Delivery Ther. 2019;9(4-s):849–54.

Dossa LH, Sangaré M, Buerkert A, Schlecht E. Intra-urban and peri-urban differences in cattle farming systems of Burkina Faso. Land Use Policy. 2015;48:401–11.

Baba S, Chan HT, Oshiro N, Maxwell GS, Inoue T, Chan EWC. Botany, uses, chemistry and bioactivities of mangrove plants IV: Avicennia marina. ISME GLOMIS Electron J. 2016;14:2.

Jamarun N, Pazla R, Arief A, Jayanegara A, Yanti G. Chemical composition and rumen fermentation profile of mangrove leaves (Avicennia marina) from West Sumatra, Indonesia. Biodiversitas J Biol Divers. 2020. https://doi.org/10.9734/bpi/nvbs/v1/12095D.

Feka Njisuh Z, Gordon N, Ajonina. Drivers causing decline of mangrove in West-Central Africa: a review. Int J Biodivers Sci Ecosyst Serv Manag. 2011;7(3):217–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/21513732.2011.634436.

Stewart M, Fairfull S. Mangroves. Profitable and sustainable primary industries. PRIMEFACT. 2008;746:9–10.

Baba S, Chan HT, Aksornkoae S. Useful products from mangrove and other coastal plants. In: ISME mangrove educational book series no. 3. Okinawa: International Society for Mangrove Ecosystems (ISME)); 2013.

Hoppe-Speer SCL, Adams JB. Cattle browsing impacts on stunted Avicennia marina mangrove trees. Aquat Bot. 2015;121:9–15.

Hammami F. Conservation under occupation: conflictual powers and cultural heritage meanings. Plann Theory Pract. 2012;13(2):233–56.

Latorre S, Katharine NF. The disruption of ancestral peoples in Ecuador’s mangrove ecosystem: class and ethnic differentiation within a changing political context. Lat Am Caribb Ethn Stud. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1080/17442222.2014.959777.

Lamsal P, Pant KP, Kumar L, Atreya K. Sustainable livelihoods through conservation of wetland resources: a case of economic benefits from Ghodaghodi Lake, western Nepal. Ecol Soc. 2015;20(1):10.

Lau J, Scales IR. Identity, subjectivity and natural resource use: how ethnicity, gender and class intersect to influence mangrove oyster harvesting in The Gambia. Geoforum. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GEOFORUM.2016.01.002.

Ramli F, Samdin Z, Noor A, Ghani ABD. Willingness to pay for conservation fee using contingent valuation method: the case of matang mangrove forest reserve, Perak, Malaysia. Malays For. 2017;80(1):99–110.

Koura BI, Dedehouanou H, Dossa HL, Kpanou V, Houndonougbo F, Houngnandan P, Mensah GA, Houinato MRB. Determinants of crop-livestock integration by small farmers in Benin. Int J Biol Chem Sci. 2015;9(5):2272–83.

Borrini-Feyerabend G, Hill R. Governance for the conservation of nature. In: Worboys GL, Lockwood M, Kothari A, Feary S, Pulsford I, editors. Protected area governance and management. Canberra: ANU Press; 2015. p. 169–206.

Musco N, Koura BI, Tudisco R, Awadjihè G, Adjolohoun S, Cutrignelli MI, Mollica MP, Houinato M, Infascelli F, Calabrò S. Nutritional characteristics of forage grown in south of Benin. Asian Aust J Anim Sci. 2016;29:51–61.

Medina LF. The analytical foundations of collective action theory: a survey of some recent developments. Annu Rev Polit Sci. 2013;16:259–83.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to M. Sodji Mathieu (1989–2018) posthumously for his involvement in this study. We also thank the ruminant herders of the coastal areas of Benin in the municipalities of Sémè-podji, Abomey-Calavi, Ouidah and Grand-Popo, and the local authorities that were interviewed and agreed to share their knowledge.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the “Fonds National de l’Innovation et de la Recherche Scientifique (FNRSIT, Benin)”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BSCMA designed the study with advice from BIK and CS. BSCMA collected the data. BSCMA, BIK, and CS designed the manuscript structure with the contribution of MST. BSCMA and BIK analyzed the data under the supervision of MRBH. BSCMA and BIK drafted the manuscript. ADPL, CS, MST and MRBH revised and critically improved the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No ethical approval was needed for this study. Prior to data collection, the participants gave oral consent to participate in the study.

Consent for publication

The herders were informed that their opinions were published in a scientific paper and given their approval.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahouangan, B.S.C.M., Koura, B.I., Sèwadé, C. et al. Ruminant keeping around mangrove forests in Benin (West Africa): herders’ perceptions of threats and opportunities for conservation of mangroves. Discov Sustain 3, 13 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-022-00082-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-022-00082-x