Abstract

The notion of junior scientists’ independence has increasingly become relevant in the evaluation of scientific excellence. In this paper, we deconstruct independence—as an element of excellence—in the context of reviewing a prestigious European Research Grant. Conducting qualitative interviews with this grant’s reviewers, we reveal five different dimensions of how reviewers construct the notion of independence: two dimensions are directly linked to the applicants’ relationship to their supervisors: reviewers were talking about independence as a result of emancipation from the applicants’ (former) supervisor and as a concept that researchers need to negotiate with them. Beyond, three topical dimensions of independence could be identified, referring to originality, networks and mobility. We further show that gender is deeply inscribed into these dimensions, especially when reviewers use their own biographical background for assessing the independence of an early career researcher. These experiences are subject to gender bias through (i) individual stereotypical pictures of masculinity and femininity and (ii) the specific norms of scientific disciplines and structures. These individual gendered constructions of independence might give space to gender bias in the assessment of independence and thus of excellence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Under the current regime of academic capitalism, researchers and research-performing organizations are competing for resources and recognition on an increasingly globalized research market (Slaughter and Leslie 2001). Thereby, research governance is building on instruments which have introduced market logics into classic humanistic concepts of research and higher education. Excellence is at the heart of this transformation (Ferree and Zippel 2015) as it is perceived as a main qualifier for outstanding performances. Performance assessments of research organizations as well as of individual researchers are omnipresent under the regime of academic capitalism and excellence is used as an indication to refer to the researchers’ ability to achieve outstanding and innovative results and to justify the allocation of resources and grants (Husu et al. 2004; O’Connor and O’Hagan 2016; Steinthorsdóttir et al. 2019). However, the criterion of excellence and its measurement is heavily contested and debated within the research community (Stilgoe 2014; Brouns and Addis 2004; Lamont 2009; Morley 2016).

From a gender equality perspective, assessments of excellence are criticized as reproducing the prevailing hegemonic male order of academia and to systematically disadvantage those who are not able to conform with these (gendered) norms (Schiffbänker and Holzinger 2016; Brink and Benschop 2012; Castilla 2008; Moss-Racusin et al. 2012; Besselaar et al. 2012; Haas and Schiffbänker 2016).

In this paper we contribute to this discussion about the gendered nature of excellence by analyzing the construction of independence as an element of excellence in the context of research funding. The independence criterion becomes increasingly important in grant evaluation processes in Europe, especially for early career grants [see funding guidelines of DFG Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft 2016, EC European Commission 2013, FWF Der Wissenschaftsfonds 2017, DFF 2016]. As excellence itself has been described as an “essentially contested concept” (Ferretti et al. 2018a) that is, above all, socially constructed and recognized reciprocally among different parties, we are equally interested in the social construction of independence and how various reviewers understand and interpret this concept. So far, the different meanings of independence and the related (gendered) practices have not yet been investigated systematically. We analyze how reviewers construct independence in the specific setting of the European Research Council (ERC) Starting Grant (StG). We focus our analysis on the question of how the construction of independence—as an element of excellence—perpetuates, changes or counteracts gender inequalities, building our argument on theories of gendered organizational practices (Brink and Benschop 2012; Acker 1990; Martin 2003; Poggio 2006).

The paper is organized as follows: In section “Theoretical framework”, we summarize the current literature about excellence and independence and their gendered nature and we present our theoretical framework. Section “Research context and methodology” describes the research subject, which is the ERC Starting Grant, how independence is formally defined and how the assessment of independence is organized in this context. It also specifies our methodological approach that is rooted in Grounded Theory and explains how we proceeded with the data. The findings on different constructions of independence by reviewers and related gendered practices are presented in Section “Findings”. In Section “Conclusions”, we discuss our findings in the light of our theoretical framework of gender and independence.

Theoretical framework

As stated (Sørensen et al. 2016a), the term excellence has become ubiquitous in discourses around research and academia in the European Union in the last 10 to 15 years (Ferretti et al. 2018a). In this process, excellence has been transformed “from a fuzzy, intrinsically understood concept (…) to a clear, relational concept which can be quantitatively measured and benchmarked” (Sørensen et al. 2016b, p. 219). In evaluations in academic settings as well as in research funding, the concept of excellence is a synonym for the highest level of scientific quality and performance (Lamont 2009; Commission 2004). It is rooted in meritocratic beliefs which select people for specific positions or distribute rewards based on their individual effort, talents, performance or merits—regardless of social categories like gender, age, race or class. These meritocratic beliefs or principles are therefore perceived as impartial and objective. Following these principles enables organizations or institutions to select the most suitable persons or talents for specific occupations or assignments. Merit and consequently excellence is implicitly assumed to be “self-explanatory”, unambiguous and measurable (Ferretti et al. 2018a; Nielsen 2015; Castilla and Benard 2010). On the level of individuals, excellence is measured through publication records, citation indexes and impact points, number of patents or membership in scientific boards, etc. (Brink and Benschop 2012).

Some scholars have critically remarked that the concept of excellence has turned into a ‘holy grail’ which everybody is seeking, but nobody really knows what it is or whether it really exists (O’Connor and O’Hagan 2016; Lamont 2009; Ferretti et al. 2018a; Deem 2009) characterize excellence as an “essentially contested concept” which is described as “appraisive, internally complex, describable in multiple ways, inherently open and recognized reciprocally among different parties” (Ferretti et al. 2018b). Through this critical perspective, excellence is not perceived as a self-explanatory or universal concept but is rather understood as complex and open to different meanings which will very likely lead to continuous discussions about the exact definition, understandings and as to whether it can be measured or not. Other scholars also argue that excellence is socially constructed as different meanings are attributed to this concept in varying social contexts (Brouns and Addis 2004; Ferretti et al. 2018a; Rees 2011). Furthermore, (Lamont 2009) emphasizes that assessing excellence is a process embedded in culture which is deeply interwoven with the social identity of the reviewers. Assessment and evaluation processes are therefore prone to be influenced by subjective practices and elements, and thus susceptible to various forms of bias.

Feminist scholars have pointed out that the concept of excellence and its meritocratic principles are not impartial and objective but are producing and reproducing multiple inequalities between men and women within research funding and academic systems (Brink and Benschop 2012; Wennerås and Wold 1997; Aksnes et al. 2011; Herschberg et al. 2015; Brink et al. 2006; Carnes et al. 2015; Girod et al. 2016; Langfeldt 2004). In the literature the gendered nature of excellence has been identified along several notions:

First, evaluation and promotion practices in academia are informed by gendered stereotypes which are linked to the masculine norms of the science system (Martin (2003); Brink and Benschop 2014; Heilman et al. 2015). These are related to stereotypical images of the ideal scientist who is constructed as a human being devoted entirely to research, spending unlimited time at work and being free of demands from other social spheres like family or community (Acker 1990).

Second, this ideal scientist’s habitus is based on competition and performance and exhibits traits of analytical competence, creativity, objectivity, and rationality which correspond to stereotypical masculine characteristics. In contrast, stereotypical feminine behaviors like interpersonal skills and collaboration are not valued in academic assessments to the same extent (Bailyn 2003; Foschi et al. 2004; Knights and Richards 2003; Bleijenbergh et al. 2012; Baer and Kaufman 2008). For instance, empirical studies provide evidence that women are perceived as less self-confident, more modest and less willing to compete compared to their male colleagues (Ellemers et al. 2004; Heilman 2001). The ideal scientist is therefore imagined as a male individual and reviewers who share these dominant stereotypes and expectations about the ideal scientist will recognize these traits and talents more in male then in female researchers (Correll 2017; Eagly and Carli 2007).

Third, research on the decision and selection process has shown that these processes are influenced by social identity processes (Haslam 2004), which means that decision makers are favoring early career researchers (ECRs) which are similar to themselves not only in terms of personality and attitudes but also regarding social categories like gender, race or socio-economic background (Haslam 2004; Schaubroeck and Lam 2002). Van den Brink and Benschop provided evidence that male supervisors tend to promote men more often (Brink and Benschop 2013; Emmerick 2006). This is explained with notions of “trust”: Male supervisors were found to trust male junior researchers more because they recognize them as similar and identify themselves with their own becoming-a-scientist (Brink and Benschop 2013; Kanter 1977).

Fourth, another aspect of the gendered nature of excellence is related to international mobility of researchers which is perceived as one ingredient for producing cutting-edge knowledge (Zippel 2018). Research provides empirical evidence that female researchers tend to be less mobile compared to male researchers (Ackers, et al. 2001; Ackers 2008; Etzkowitz et al. 1994; Joens 2011; EC European Commission 2016). This lower mobility is often attributed to parenting issues (Shauman and Xie 1996; Anders 2004; Ackers 2005; Uhly et al. 2015), a higher involvement of women in childcare activities and a lower likelihood to move without their partner (Xie and Shauman 2003; Ackers and Stalford 2007). In addition, recent research on recruitment procedures (Herschberg et al. 2015) has shown that international work experience is often a tacit, emergent selection criterion for post doc positions at European universities. As a tacit criterion it is not explicitly defined and therefore subjected to personal interpretations of committee members. Committee members consequently apply subjective standards in the assessment of international mobility. Herschberg et al. (Herschberg et al. 2018) have also identified gendered practices of committee members when these assume that female ECRs are not or less mobile than their male competitors because they expect women to be the primary caretakers for children (Herschberg et al. 2015b).

Fifth, excellence has been criticized for neglecting the power of gate-keeping and networking (Husu et al. 2004; Brink and Benschop 2012). Bagilhole and Goode (Bagilhole and Goode 2001) found in their qualitative study that male scientists benefit from a supportive (male) network which takes their competence and excellence for granted, while women need to actively invest in formal and informal relationships in order to be promoted. The lack of support for women in academia has been discussed in various studies and is mostly related to the preference for homophile ties (Brink and Benschop 2014; Bird 1996; Hearn and Husu 2011). Men support men more often because of their social resemblance. Women are thus frequently not involved in male networks and do not benefit from the support offered through these networks like sponsorship and encouragement (Brink et al. 2006; Rhoton 2011; Walby 2011). Male-dominated networks therefore make it more difficult for women to succeed in science but also to be perceived as excellent (Husu et al. 2004; Durbin 2011); Sabatier et al. (Sabatier et al. 2006) showed that women in the Life Sciences need a higher involvement in professional networks than their male colleagues to be promoted to professorship. Van den Brink et al. (Brink et al. 2006) demonstrated that informal, closed recruitment procedures are favoring male ECRs who are embedded in informal or formal networks and who are likewise to be informed about these positions and encouraged to apply by their sponsors. Those network ties—often appearing among applicants and reviewers—increase their chances to be selected significantly (Brink and Benschop 2012; Wennerås and Wold 1997).

Therefore, we conclude that gender bias is inscribed into the concept of excellence: on the one hand, bias can be related to the definition of the concept and to its criteria or indicators (Wroblewski 2014; Nielsen 2017). Based on the work of Acker (1990), these criteria and indicators can be understood as reflecting masculine norms and values based on the stereotypical image of the ideal scientist. Women or men whose life circumstances do not conform to these implicit standards do not share the same chances to be successful. On the other hand, gender bias can occur in the application of criteria in the evaluation process: when the assessment of female applicants is influenced by gendered role expectations and gendered stereotypes which lead to different assessments for men and women although they are equally qualified. (Correll 2017) provides four examples of such practices: (a) the benchmarking bar is higher for women than for men (see also Wennerås and Wold 1997), (b) evaluators inquire performance and merit of women more thoroughly, (c) evaluators are weighting and shifting criteria to support their favored ECR and (O’Connor and O’Hagan 2016) conflicting judgements of competence and likability for women but not for men (Heilman 2001; Ackers 2005).

In the following section, we highlight how independence—as an element of excellence—might be subject to the same gender biases and practices as excellence.

Independence as an element of excellence

Only recently, criticism of excellence has been enriched with an additional aspect: traditional excellence indicators point to past research output rather than to the potential of a researcher or a research project (Haas and Schiffbänker 2016). Research funding organizations have therefore increasingly started to focus on independence as a crucial element to demonstrate the potential for scientific excellence when it comes to the evaluation of early career researchers (ECRs). These researchers have to prove their individual talent by exhibiting an autonomous publication record that shows that they have been able to conduct research without their former supervisor (among others, cf. the funding guidelines of DFG Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (2016); EC European Commission 2013; FWF Der Wissenschaftsfonds 2017; DFF 2016). As an example the aim of the DFG-funded Emmy Noether Program in Germany is to assist early career researchers in gaining scientific independence by establishing an independent junior research group (DFG Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft 2016). In the US, the National Institute of Health even offers a specific independence guideline for Post Docs (NIH 2017).

However, the increasing relevance of independence in research funding has only rarely been reflected in academic research so far. (Besselaar et al. 2012) introduced an approach to define a concept for measuring independence. They developed a quantitative independence indicator for early career researchers which includes three sub-dimensions: the first dimension refers to the social independence of early career researchers from a former supervisor; the second one relates to their cognitive or thematic independence which measures the development of independent topical clusters of early career researchers compared to the ones they are sharing with their (former) supervisor. The third dimension deals with the innovativeness and novelty of the research stream and focus. The defined aim of this indicator is to provide an advanced way to measure excellence by focusing on the applicant’s potential for innovativeness and novelty (Besselaar et al. 2012).

Although there are a lot of studies investigating the application and weighting of excellence criteria in peer review and selection processes, there are no studies which are reconstructing the concepts of independence and related gendered practices of evaluators. One of the first empirical studies conducted on review panels revealed that reviewers found it difficult to assess independence—as the definition of independence and potentially applicable indicators were not clear (Ahlqvist et al. 2015). However, they did not link independence to excellence and thus to the gendered notion of excellence.

In our research, we are building on social theory which conceptualizes gender as socially constructed through situated practices and negotiated in face-to-face interactions (Brink 2010; Poggio 2010; Ely and Padavic 2007). Drawing on the work of Acker (1990) and others (Ely and Meyerson 2000; Gherardi and Poggio 2001; Martin 2006) enables us to understand that socially constructed images of men and women, of masculinity and femininity are inscribed into and reflected by institutional structures, cultural symbols and social interactions although they appear as gender-neutral. Gender and gender inequalities are therefore produced and reproduced through social practices in organizations. These are called gendered practices if they explicitly or implicitly distinguish between men and women or between masculinity and femininity, favoring men over women or vice versa (Brink and Benschop 2012; Ely and Meyerson 2000). These gender practices are mostly happening in an unintentional, non-reflexive way. That is why we expect in our current study that independence and gender are constructed at the same time: While reviewers talk about excellence and independence they are doing or undoing gender (Pecis 2016; Kelan 2009).

Building on the outlined theoretical framework, our study will advance the understanding of the evaluation of independence in three aspects: (a) By reconstructing different dimensions of independence in a specific assessment process, we are able to highlight the ambiguity of this criterion. (b) Building on the literature about the gendered nature of excellence, we are able to show how these different dimensions are inherently gendered. (c) Through the lens of our theoretical framework, we are able to also identify gendered practices in the application of independence.

Research context and methodology

The empirical data of our study is drawn from a research project investigating the reasons for lower success rates of female compared to male applicants of the Starting Grant (StG) awarded by the European Research Council (ERC). It is a highly prestigious grant which addresses early career researchers from 2 to 7 years after their PhD with a maximum funding of EUR 1.5 mln per person. As one of the most important funding instruments to set up a career in science, the Starting Grant has not been allocated to female and male applicants equally so far, as over the years and with regard to different grants, men had performed better. When analyzing the StG 2014, we found that lower success rates for female vs. male ECRs occurred more often in the Life Sciences (− 3%), compared to Physics, Engineering (+ 2%) and Social Sciences & Humanities (no difference). The following analysis thus focuses on the Life Sciences.

The table illustrates the different success rates of men and women in the sector of Life Sciences in 2014.

The differences in success rates show a broad range from 14% points lower to 11% points higher success rates for women. However, in seven out of nine panels, success rates for women were lower compared to those of men (see Table 1). From these data emerges a need to better understand the lower success rates of female applicants and differences between panels; we therefore first describe the process of grant evaluation.

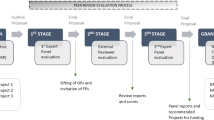

Application process

The process starts with the applicants submitting their grant applications, which are evaluated in two phases, both including a remote assessment and a panel meeting.

The first step in the evaluation process is to allocate each proposal to three or four reviewers who carry out their assessments at home and submit their results using an online system. The research project and the Principal Investigator PI are scored by answering questions that aim to operationalize ‘scientific excellence’, which is defined as the decisive criteria for funding by the ERC. The reviewers have to score (i) to what extent the proposed research addresses important challenges; (ii) to what extent the objectives are ambitious and beyond the state of the art (e.g. novel concepts and approaches or development across disciplines); (iii) whether the proposed research carries high risk or high gain; (iv) to what extent the PI has demonstrated the ability to propose and conduct ground-breaking research, (v) whether their achievements have typically gone beyond the state of the art and (vi) to what extent the PI provides evidence of creative independent thinking.

Based on the remote assessment, a ranking of all proposals is produced that serves as a basis for the discussion in the panel meetings. A lead reviewer, one of the 3–4 reviewers who remotely assessed the respective proposals, introduces and discusses them with the other remote reviewers. The other panel members contribute to the discussion which is based on the potential of the PI and the scientific impact of the project. At the end of the first phase meeting, panel members need to agree upon the proposals for the second phase, which are usually around 30% of the applications.

The second assessment phase works similarly, but up to five additional external reviewers called ‘referees’ are asked to rate the proposals remotely. The referees provide specific scientific expertise for the assessment but do not participate in the panel meetings. In the meetings, applicants are invited to present their research project in a set time frame, leaving further time for questions. After the presentations, panel members discuss the excellence of each proposal to agree on a list of ECRs that should be funded, which is then distributed to the Scientific Council of the ERC for the final decision.

We want to highlight two main aspects of the evaluation context. First, during the panel meetings, the reviewers need to agree upon the ECRs, although they are related to different cultural contexts, institutional settings and experiences and might therefore have different opinions about whether the applicants demonstrate ‘creative independent thinking’. As there are no standard criteria on how to assess excellence in the panel meetings, the reviewers need to agree on collective norms in their assessment (Lamont 2009). Panels consist of a panel chair and 10 to 16 international reviewers who are expected to maintain the highest standards of ethics and to bring in their expertise and scientific seniority. Reviewers are appointed as individuals and not as representatives of their discipline or any organization. Being aware of the fact that those reviewers come from different nations, institutions and research communities, we hypothesize that their views on the (ideal) ECRs might also differ. In line with a social constructionist perspective, we are interested in how assessments include different perceptions of the ECR.

Second, independence is constructed as one element of excellence in the documents of the ERC Grant, specifying that the applicant “must have already shown the potential for research independence” (EC European Commission 2016, p. 21). This is directly linked to independent publication activity as the ERC rules for submission and evaluation state that the PI needs “having produced at least one important publication without the participation of their PhD supervisor” (EC European Commission 2014, p. 20). Apart from that, there are no established criteria on how to assess independence.

Our analysis is based on semi-structured interviews with 32 reviewers (18 male, 14 female) who participated in StG panel reviews in 2014, including three panel chairs. While 25 interviews were done face-to-face, seven interviews were conducted by telephone or Skype. The interviews lasted between 30 min and 2.5 h. For the analysis all interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

The interviews were reflecting the different stages of the official evaluation process. Thus, reviewers were asked about (i) their understanding of being a reviewer, (ii) the criteria and definition they personally apply when assessing excellence of applicants, and (iii) the challenges and contradictions they have faced in the panel negotiations so far. The interviewees have not been explicitly asked about their understanding of independence or how they assessed this criterion. Nevertheless, reviewers were referring to independence explicitly or implicitly when talking about assessing excellence. Thus, we were looking for different dimensions and notions of independence that were depicted in the data to understand evaluation practices. What do reviewers think is independence? How did they evaluate and judge it? Were there any difficulties or challenges or were they clear about how to assign this criterion to applicants? And if they did, how exactly did they proceed? Through this open approach we were able to reconstruct how reviewers view and understand the independence criterion.

Our research interest required a Grounded Theory approach (Glaser and Strauss 1967), where data are addressed without predefined categories or hypotheses. Rather, Grounded Theory generates theory inductively. The process of developing the most important themes follows a continuous comparison of data and hypotheses, explicitly looking for contradictions and/or consistencies in the data. A three-step approach was applied: first, we started with getting familiar with the data by systematically looking for references to the terms of independence and dependence, from either an explicit or implicit point of view. Two researchers read through the interviews repeatedly and collected all relevant expressions and references. Second, we followed an open coding procedure: starting from the key concepts that were mentioned in the interviews, descriptive codes were assembled and data were summarized into categories. We therefore used different forms of paraphrasing the reviewers’ statements and discussed and further analyzed these codings in close collaboration of all authors. Third, we started looking for the concepts “behind” those categories and continuously compared and discussed them. Through different forms of structuring, restructuring and discussion, we were able to identify patterns and to reorganize our data making use of our literature knowledge, expert know-how about the research field and our academic background. To give an example, we used the quantitative model of van den Besselaar et al. (Besselaar et al. 2012) and contrasted the developed codes with their categorization of geographical, social, and topical independence. Having noticed that we did not consider geographical independence in our system, we went back to the data and explicitly looked for concepts that addressed the issue of geographical independence. We finally extracted those notions that had been referred to as “mobility” by the reviewers. Thus, the process of developing the most important themes followed a continuous comparison of data and hypotheses about the underlying concepts, explicitly looking for contradictions and/or (in-) consistencies. We continued to constantly compare, break down, discuss and group concepts until we were able to present inductively generated dimensions of independence.

Findings

From the selected quotes and remarks of reviewers about independence we extracted two sets of dimensions: one related to the content or meaning of independence and reflecting different pictures of independence, the other referring to challenges in the evaluation of independence. In the former, the categories were built upon the basis of the reviewers’ illustrations of what they found relevant about the criterion of independence, such as mobility or the emancipation from a former supervisor. In the latter set of dimensions, the findings were based on statements highlighting the reviewers’ experiences and observations in panel discussions. In this context, also ambivalences and contradictions that emerged during the evaluation process became part of the analysis. In some of the dimensions, gender or gender bias—meaning a different view on male and female ECRs—are explicitly mentioned by the reviewers (see Table 2).

In the following, we discuss the dimensions of independence that we extracted from the data in detail. To illustrate our findings, we use selected key quotes and interpret them against the backdrop of our theoretical framework.

Independence demands distancing from a former supervisor

I think we really need to encourage the younger researchers to strive for independence and really distance themselves and come to a new level. (…) I think peer research will really suffer if we get this ‘inbreeding’ in science, which this ultimately will lead to when you work closer with your former supervisor. (Reviewer 12)

In this statement, the reviewer explicitly connects independence to an emancipation of ECRs from their (former) supervisors. Independence is necessary in order to stop the “inbreeding in science” and to get “to a new level” which can refer to new research ideas and approaches. ECRs hence need to “distance themselves” from the supervisor, which can have a topical but also geographic dimension. By acknowledging the act of distancing to become independent, however, the reviewer implicitly points to a crucial role of supervisors for the development of ECRs excellence: While pursuing an academic career, ECRs need a senior supervisor to encourage them and to introduce them to the scientific community (Schiffbänker and Holzinger 2016; Baruch and Hall 2004; Elg and Jonnergård 2003). The supervisor serves as a sponsor for excellence and connects the ECRs to important topics and their own network. In this way, ECRs learn the standards and norms of scientific communities, get the chance to prove their excellence and become recognized as valuable members of the scientific community. The scientific system is thus characterized by high dependence in the beginning of a career. In the early post doc phase, these dependence structures are still salient so that they hardly allow for the real emancipation from the supervisor (Baruch and Hall 2004). The reviewer is well aware of this aspect and talks about the necessity to distance oneself from a former supervisor to “come to a new level”. However, the ability of early career researchers to distance themselves from their supervisors is attributed more to men than women, as stated in the following quote from another reviewer:

In general, women are publishing longer with their doctoral advisor than men. (…) In my experience women are more content working with someone they already know. It gives them security. Men, on the other hand, strive to break free as soon as possible and make something of their own. (Reviewer 31)

In this quote, the reviewer describes his perception of women as striving less for independence compared to their male colleagues. The reviewer states that women aim less “to break free” and to develop their own research topic or team, while men, in contrast, aim to become independent as early as possible and “to make something of their own”. He even refers to the fact that women are “more content” publishing with someone they already know, someone they can rely on. Behind this quote we find an existing gender stereotype that conceptualizes women as team-orientated and relying on social ties (Abele 2003). By using terms like “in general”, the reviewer’s own experiences are presented as an “empirical fact” rather than personal observations. Further, the quote incorporates a strong dualism between men and women; assigning the ideal picture of distancing oneself from a former supervisor to men; and presenting women as the opposite. In this dimension of independence, gender stereotypes are activated which attribute agentic behavior to men, whereas women are seen as passive and striving for security. Thus, we assume that female applicants will be disadvantaged if the assessment of independence is conceived as an active emancipation from the supervisor which is more ascribed to men than to women.

Independence needs to be negotiated by the junior

Secondly, we found that reviewers do not see independence as something simply gained, but as something that actively needs to be negotiated by early career researchers. Connecting to the aforementioned quotation by Reviewer 12, who said “I think we really need to encourage the younger researchers to go for independence and really distance themselves and go to a new level (…)”, we reconstruct that independence does neither occur spontaneously, nor is it connected to a certain career step. Instead, it needs to be strategically developed by ECRs who might either face encouragement or neglect or rejection. The “act of emancipation”—which is also inscribed in the request to have at least “one important publication without the participation of their PhD supervisor” (EC European Commission 2014, p. 20)—requires a certain negotiation power. It thus depends on the ECRs’ determination to negotiate with their supervisor:

The supervisor doesn’t want any competition. This competitiveness is still very dominant. And perhaps women think that they don’t want to work against their former boss. And men think: ‘I will show him!’. Women are perhaps less brutal negotiating [for independence]. (Reviewer 1)

This quote shows that the reviewer does not perceive women as competitive and insisting on their independence from their supervisor. Women are described as seeking collaboration, consensus and avoiding conflicts. The quote therefore points to a gender stereotype, classifying men as more assertive than women; and strengthening the stereotypical idea of women wanting to collaborate (Abele 2003) and avoid competition (Heilman 2001). At the same time, the quote reveals the necessity of being competitive in order to be successful: Only with the notion of being a potential competitor to a former supervisor, ECRs are potentially able to climb the scientific career ladder. This involves being “brutal”, being ready to fight, also against those who have been supportive along their own career trajectory. The gender-stereotypical ascription that women “do not want to fight” questions their ability to negotiate for independence. If women are constructed as less prepared for this “fight”, this could be a potential disadvantage in the evaluation process.

Independence is associated with originality

“… if they come from a big lab, you follow what they are doing there, so this is not creative thinking.” (Reviewer 16) The reviewer states that in big research laboratories, researchers are working in larger teams and therefore do not develop independence. Instead, especially younger researchers and team members are expected to fulfill what others have devised and masterminded. They are therefore constructed as following instructions or directions but not as developing “creative thinking”. Here, independence is linked to creativity and originality as well as to pursuing one’s own ideas and interests. It demonstrates the ability to make new connections between diverse knowledge bases, in ways diverging from the norm, to reach “out of the box” and develop new approaches and solutions as a result.

The reviewer makes a clear distinction between creative thinking, which contributes to individual independence, and working in a large team, which is understood as being a small part in a bigger machine. Creative thinking distinguishes independent researchers from the great bulk of researchers who just perform specific tasks and follow the ideas of others. Consequently, the reviewer presumes that creativity is more a trait of outstanding individuals or geniuses than of groups or teams. However, this contradicts research findings that describe creative thinking as an interactive and collective process (Paulus 2000; Pirola-Merlo and Mann 2004). In diverse research teams, different knowledge bases, methodological approaches, skills and perspectives are available, producing an inspiring and creative environment that is perceived to foster originality and innovation (Diaz-Garcia et al. 2013; Joshi 2014; Knippenberg et al. 2004).

Although the quote above does not imply a gender notion, we can assume that gender does play a role in the evaluation of creativity and originality. Research has demonstrated that the archetypical creative persona is considered to be male (Baer and Kaufman 2008; Abele 2003). Proudfoot et al. (2015) showed in various field experiments that creativity is more ascribed to men than to women even when they produce identical outcomes. Besides, they provided evidence that creativity is perceived to originate more from stereotypical male behavior than from specific competences: from the perspective of the test subjects, creativity is facilitated when men behave in masculine ways, but not when women behave in the same way. This connotation of masculinity and creativity may be one reason for gender bias in peer review processes. When the perception of creativity is gendered, it is more difficult for women than for men to receive appropriate credit for their creative thinking.

Independence is demonstrated with a distinct network

“She has not really established those collaborations yet … all her collaborations were people who’d been collaborating with her big boss, where she’d picked up his existing network.” (Reviewer 1) In line with the notion of emancipating from a former supervisor, the reviewer refers to the fact that a female applicant has not established her own collaborations yet. Establishing distinct collaborations is constructed as an important need and request for ECRs to prove their independence. The reviewer recognizes the establishment of a separate network as a prerequisite for independence. Having developed distinct collaborations and networks is perceived as evidence for the fact that ECRs are accepted and appreciated members in the research community and exhibit potential for excellence. The demand is to have a specific kind of collaborations (“those collaborations”), probably similar to those of her boss or supervisor. As the reviewer portrays him as being the big boss and thus an attractive and excellent network partner, the attribution might be that all members of this network are similarly excellent. In contrast to that, the female applicant is pictured as ‘little’, as someone only picking up or borrowing what others have developed, not able to set up her own thing, not quite committed and lacking initiative. She is therefore portrayed as being passive and dependent on her “big boss” when it comes to establishing new ties for research collaborations. She is perceived as not knowing who to address to become a network member; or her research ideas are not perceived as unique, attractive or excellent enough that others researchers would join. In the global research community, she is not considered to be well-positioned and to have established her individual arena yet.

The above statement further illustrates that the development of a network of one’s own is seen as a process, something that has to be developed over time. The reviewer argues that distinct collaborations have not been established “yet”; they can probably evolve in the future.

Various scholars have demonstrated that access to existing network structures is often limited and more difficult to gain for women. This is explained by a lack of time resources (Schiebinger 2000), a lack of support to enter existing networks (Husu et al. 2004) and dominance of men in most networks as well as homosocial similarity (Brink and Benschop 2014; Hearn and Husu 2011). The latter means that when a network mainly consists of men, those will prefer to include additional men, while women both are and will feel less invited.

Being aware of these facts, a well-developed network of collaborations could be more ascribed to male than female ECRs. When independence is hence constructed as having established a distinct collaboration network, reviewers need to be aware that women face challenges and limitations as a result.

Independence requires geographic mobility

If someone has done good things in one place and again does good things in another place it is like independent points, showing you this person is better than others that have done excellent things in just one place. You could have the contaminant effect working only in one place with the same people, so that´s an important point in that respect. (Reviewer 25)

The reviewer argues that mobility makes the difference: a researcher who is able to do research in different places is considered as more independent as another one who has done research in only one organization. The “independence points” the reviewer refers to are linked to one’s own establishment in different (cultural) settings, and mainly serve as “proof” of one’s own, independent research because it has been carried out in two different places at least. ECRs moving to different places are thus perceived as agentic, powerful and being able to integrate themselves into a new environment. They are perceived as more excellent than researchers who are just working in one place. In contrast, researchers who are not mobile are described as “narrow or lacking curiosity” (Reviewer 24), which refers to the picture of the ideal scientist who is constantly looking for new challenges.

Interestingly, any move to another research organization is perceived as a further step to independence. “If you are in a new location you will naturally diverge” (Reviewer 3) This reviewer points out that doing research in a new location is a positive step. ‘In this perception, ‘new’ may be different to the place where the applicant has done most of their previous work and probably also where their supervisor is working. Becoming more distinguished and thus more independent is closely linked to be in another place which refers to geographic mobility; most of the time this means moving to another country. International mobility fosters gaining different and new impressions, experiences, competences and skills to enlarge one’s individual research potential. The reviewers stressed that by moving to another institution, researchers have the chance to get closer to the centers of excellence in their field. They gain important experience by working at places that are more prestigious and have a higher scientific reputation. Working with and learning from the best in the field offers inspiration and enlarges one’s scientific network, which may later lead to more citations and a higher scientific impact (Elsevier. 2017). Mobility in this context is considered as a pathway to excellence as it is supposed to enlarge a researcher’s scientific capacity and independence (Zippel 2018).

Yet it could be observed that mobility is discussed differently for male and female applicants in evaluation panels:

Women don't move as quickly and as long as men to another country to make part of their research there. At the same time, I noticed that some men have never moved out of their university (...). They start their PhD at the same university ... And they also become professors at the same university. And everybody finds that they have an excellent CV. And for women it is sometimes mentioned that she didn't go abroad for her PhD or after her PhD. I think there is a gender bias in the assessment of the applicant’s trajectory. (Reviewer 32)

This reviewer refers to attributions or observations of women going less often abroad and if they do, they stay there only for a shorter period of time. But also male colleagues stay within the same university and show no geographic mobility; nevertheless they are perceived as excellent. The quote reflects that for men’s promotions, the mobility criterion is not essential, obviously other criteria are relevant. Referring to observations in grant review panels, the reviewer describes a similar phenomenon, namely that women are more checked for their mobility and that thus the assessment of women’s trajectories is biased.

This observed gender practice in the evaluation is linked to discussions about a lower mobility of women in science as one major reason for their career disadvantages (Joens 2011; Geuna 2015). While not all women are less mobile and have family obligations, however, immobility is attributed to women in general and thus this constitutes a gender stereotype. Also women without care obligations or with private care arrangements are perceived as less or non-mobile.

Reviewers who share this attribution question and subsequently check mobility more for female applicants. Conversely, men are perceived as mobile; mobility is assumed to be a masculine quality (Abele 2003). In evaluation panels, bias could arise when reviewers assume that women have a lower mobility as this may influence their assessment. Then mobility is not or less questioned and thus discussed for male applicants; mobility is checked for women only or more thoroughly than for men. Thus, double standards are applied to female and male candidates. More precisely, mobility is judged for female grant applicants at a higher standard, a finding (Herschberg et al. 2018), also revealed for academic positions in their analysis of international mobility. A construction of independence that relies on high mobility of the individual researchers affects women negatively as this evokes stereotypes about mobile men and settled-down women who take care of child-rearing and household duties.

Besides those five different content-related ideas on independence, reviewers did also talk about challenges arising when independence is evaluated in practice.

Independence is difficult to judge for early career researchers

I think ‘independent’ was also one criterion which I thought was odd because indeed these people come from their Post doc, so one cannot yet evaluate them on their independence, in my opinion. One can say: ”Ok, they have done great work as a Post doc“. And this would mean together with a supervisor. So it would be ”participated in great work”. Yes, that they have done a great job—often in a very good environment. (Reviewer 6)

In this quote, the reviewer is highlighting the difficulty to identify the exact notions of independence in the evaluation practice. He even conceptualizes the criterion as “odd”, as he thinks that the early career phase does not allow for scientific independence, but only for the “participation in great work”. Therefore, independence cannot be assessed for ECRs as it still needs to develop over time. Their status as post docs is essentially defined as dependent on a supervisor and they are lacking sufficient opportunities to become independent.

When talking about the difficulty to assess independence in an early career stage, reviewers refer to the implicit requirement for candidates to leave their former supervisor behind and emancipate from his or her network—while at the same time being well aware that candidates still benefit from the stable support system of a senior researcher, but also from the “very good environment” they are situated in. The reviewer points out that these applicants participate in great work which means that they do it together, probably supporting a leader of a research team or project in a specific or various tasks. This career phase aims to lift and develop potential and the ECR can prove it when collaborating with excellent peers. However, these opportunities to develop new ideas and streams of research in such invigorating and creative places are neglected if only the distance to the former supervisor is assessed.

Independence is difficult to identify in research teams

He says that he was doing only a very small part of that big research and that he was characterizing this or that interaction for three years. So he doesn’t know much about other techniques. It doesn’t mean that he’s coming home being able to start his own research which will be of such high quality to be published in a very good journal. (Reviewer 28)

The reviewer states that research conducted in a larger group or team does not allow an easy identification or assessment of the individual creative contribution of a researcher. Firstly, this holds for the research process: In the quote, the reviewer describes an applicant’s contribution to a big research project as limited to a specific task over years, while other parts of the research are carried out by different colleagues. The ECR develops competences related to this specific task, while the colleagues’ skills are not processed. The quote pictures the work organization as increasingly apportioning responsibilities and tasks to different members of a larger research team. Here, success is based on optimal collaborations between specialized team members, while individual contributions are not foregrounded. For reviewers, this individual contribution is thus difficult to identify.

Secondly, reviewers refer to the fact that not only in the process of research, but also in the publications, the individual independent contribution is hard to identify and to evaluate. “Someone is in an excellent lab in the US (Harvard) and then he comes with a paper as one of many authors. He's somewhere in the middle and it is a Nature paper, so impact 30. (...) he was just doing some very particular research, one part of excellent research. But it depends on laboratory material of course, on infrastructure and how much they are independent in their research. (Reviewer 28)

Working in an excellent team offers the opportunity to become a co-author in highly ranked publications at an early career stage. The resulting high impact factor is often used as an indicator for excellence. In the concrete evaluation practice, however, the reviewer states that it is particularly difficult to judge a researcher’s contribution and originality when an impressive scientific outcome like a Nature publication is produced by a large number of authors.

Both quotes verbalize reservations to found a positive assessment of an applicant’s independence on successful collaboration in a research team. The research output stemming from this kind of collaboration does not necessarily demonstrate the applicant’s research competences or abilities to develop a highly excellent and original research topic of their own. In the quote above, collaboration in teams objects or at least does not facilitate independence of early career researchers. This is in contradiction to other dimensions of independence presented above which value (distinct) collaborations and network ties as an indication for the ability of early career researchers to distance themselves from their former supervisors.

Independence is ascribed to male rather than to female candidates

You’re not less independent as a woman, just because you still co-publish with either your PhD or Postdoc supervisor than if a man would do it. There is no difference. But that is clearly seen upon as differently. And the male candidates come out much better than the female ones in that aspect. (Reviewer 19)

In this statement, the reviewer describes that when female and male applicants both co-publish with their supervisors, they are assessed in a different way. Although both men and women do not comply with the informal request to publish without their supervisor, this reviewer reports that panel members distinguish by sex in the way that male applicants “come out much better than the female ones”. This practice favors men and challenges women.

Evaluation practices like this one demonstrate the double standards applied to female and male applicants by reviewers in the evaluation of independence.. Based on existing norms and personal observations and experiences, reviewers have divergent assumptions about men’s and women’s independence. When women are expected to be less independent than men, they will need to put more effort into proving their independence. Thus, these gender stereotypes can result in gender bias in the evaluation of independence. This demonstrates that the same merit or behavior is assessed differently; that different standards are applied to female versus male candidates. Double standards in the assessment of independence are also revealed in the following quote, which explicitly mentions that reviewers attribute independence more “naturally” to men than to women: “(…) females’ independence is questioned more than males’ is.” (Reviewer 12).

Conclusions

In our research we followed the idea that independence—as an element of excellence—is worth a deeper analysis and deconstruction as it only recently has become relevant in grant evaluation processes. In this paper we analyzed how members of evaluation panels talk about and evaluate independence. We were explicitly interested in the constructions of independence of reviewers and whether the different dimensions we have identified are intertwined with gendered images and gendered practices.

We identified five different dimensions of independence which describe distinct concepts on how independence is constructed. Two of them are directly linked to the applicants’ relationship to their supervisors: on the one hand, reviewers were talking about independence as a result of emancipation from the applicants’ (former) supervisor and, on the other hand, independence is portrayed as a concept that researchers need to negotiate with these supervisors. Originality, the establishment of a distinct network and mobility are three additional dimensions of independence that emerged from the data.

We were able to show that these five topical dimensions partly face the same gender biases as the concept of excellence: firstly, competition and performance are inscribed in the directive to gain independence and both are less ascribed to women than to men. Negotiation power is more strongly ascribed to men who are perceived to be agentic, creative and striving to “break free”. Secondly, geographic mobility is not only part of the excellence concept but is inseparably linked to the concept of independence. However, the mobility discourse follows an explicit masculine norm (Heilman 2001) connecting the picture of the ideal scientist who is devoted to an all-life commitment to science (Acker 1990). In this context, women are conceptualized as less mobile. However, these gender inequalities are not related to different traits of men and women, but are based on the masculine structures and norms of the science system and on a gendered division of labor in society. Women are still taking over the major responsibilities for childcare and housework and thus are not as mobile as their male colleagues who are less involved in such activities (Ackers 2005; Ackers and Stalford 2007). Therefore, traditional male life contexts favor higher mobility and thus privilege people without additional care or family obligations. Thirdly, collaborations and networks are—paradoxically—seen as a basis for gaining independence: Only stable “dependence” structures at the beginning of a career as well as close ties to a (former) supervisor allow for distancing from these ties and for establishing oneself in foreign places where young researchers will “naturally diverge”. However, dependence structures with former supervisors privilege male candidates, as male candidates access (‘old boys’) networks more often, while women do not have the same prerequisites to connect to other researchers and/or establish their own networks that easily (Brink and Benschop 2014). Additionally, women are considered as being “content” with focusing on team work.

Considering evaluation practices, there is ample evidence in the analyzed quotes that the concept of independence is connoted with masculinity and male traits, whereas femininity is associated with dependence and a stable relation to their supervisors. Reviewers, for example, argue that independence needs to be negotiated and describe women as less able or less willing to negotiate and fight. Women are thus not perceived as equally able to achieve independence from their supervisors. Subsequently, these gender biases contribute to a different treatment of men and women in the assessment process, mostly to the disadvantage of women.

The concept of independence thus is inherently gendered—as an element of excellence but also because the dimensions are differently applied for men and women. We summarize that independence is ascribed to male rather than female applicants and that based on gender stereotypes, mechanisms are in place to up- or downgrade applicants.

Furthermore, we were able to show that independence is understood differently by reviewers: independence is not a formal criterion which can be easily measured. The different dimensions exhibit ambivalences and contradictions that lead us to the conclusion that independence is not a homogenous concept. Rather it comprises meanings which are evoking different understandings and in further consequence different assessments. Reviewers, on the one hand, highly argue for distancing from the supervisor socially and topically, but on the other hand point out that ECRs need time to develop independence. Another contradictive aspect is that one’s own collaborations and network ties without the former supervisor are perceived as an indication for independence. Simultaneously, reviewers argue that assessing independence when applicants work in bigger research teams is difficult as it is not clear what the concrete contribution to the research outcome has been.

Contradictions and limitations in the construction of independence become relevant in the assessment of independence as clear instructions for how to evaluate the concept of independence are missing. This leaves room for personal interpretations of the concept and for ambiguities. Although the ERC defined one concrete indicator for assessing independence, namely “having produced at least one important publication without the participation of their PhD supervisor”, reviewers apply their own understandings of independence when assessing applicants and thus bring in their own constructions of independence. In evaluation panels, independence is constructed individually and applied unsystematically. We hypothesize that one reason why reviewers did not show a consistent understanding of independence was that they are interpreting formal guidelines individually against the backdrop of their own experiences made throughout their career. Thus, personal biographical experiences co-construct independence in the evaluation process. Partly, gendered practices can be derived from this hypothesis: Professional biographical experiences are permeated with images of men and women. For example, reviewers have gone through their own emancipation processes from a former supervisor and have certain experiences with female and male junior researchers, and their (perceived) willingness to fight for independence. These own experiences, connected with the paradox that women are perceived as less committed to their careers (Ellemers et al. 2004) often lead to a systematic—though unconscious—lower evaluation of female applicants.

Our research provides an indication that, due to the lack of formalizing independence, gender bias becomes relevant not only within in the concept of independence but also perpetuates evaluation practice. Consequently, we understand independence as a gendered concept which evokes gender stereotypes and subsequently leads to gendered evaluation practices which disadvantage women.

However, our research faces some challenges that have to be addressed in the future in order to get a more holistic picture of the concept of independence: One limitation of our research is that we were not able to observe the decision-making process in the panel meetings as we were not allowed to take part in these panels. This would have enabled us to directly observe gender practices related to assessing independence and to determine their influence on concrete decisions. Although we concluded that biographical experiences might influence the construction and the application of independence, we did not discuss whether and in which way the sex of the reviewer and the panel composition are affecting gender practices in the peer review process. Distinguished gender practices—like double standards, dropping of the independence/mobility criterion or questioning the performance of women more than that of men—are often applied unconsciously (LERU – 2018). The interviews revealed a different level of awareness about how gender is inscribed into the evaluation practices or the science system on the whole. In this context, (Joshi 2014) has demonstrated that the use and evaluation of women’s expertise compared to men’s differ by the sex of the assessor and the gender composition of the team. While highly educated female and male team members were evaluated more positively by female actors than by male actors in the team, “the expertise of highly educated women was used to a greater extent in teams with a higher proportion of women than in teams dominated by men” (Joshi 2014, pp. 228–229). Therefore, the team composition might also have an impact on the evaluation of women’s expertise. As reviewers are recruited from different research organizations and national research systems, we assume that different meanings of independence might be related to these organizational and national contexts. When assessing applicants for the ERC Starting Grant, reviewers might make use of independence constructions which they are more familiar with than the ERC criteria. Both aspects could be subject to further research. One last shortcoming of this paper might be that the contained arguments build on quotes coming from the Life Sciences only. Further research is necessary to investigate concepts of independence in different disciplines and to analyze whether they are related to gendered assessment practices in different disciplines.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality agreements with research participants including the ERC.

References

Abele A (2003) The dynamics of masculine-agentic and feminine-communal traits: findings from a prospective study. J Pers Soc Psychol 85(4):768–776

Acker J (1990) Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: a theory of gendered organizations. Gend Soc 4(2):139–158

Ackers L (2005) Moving people and knowledge: scientific mobility in the European Union. Int Migr 43(5):99–131

Ackers L (2008) Internationalisation, mobility and metrics: a new form of indirect discrimination? Minerva 46(4):411–435

Ackers L, Stalford H (2007) Managing multiple life courses: the influence of children on migration processes in the European Union. Soc Policy Rev 19:321–342

Ackers L et al (2001) The participation of women researchers in the TMR marie curie fellowship 1994–1998

Ahlqvist V, Andersson J, Söderqvist L, Tumpane J (2015) A gender neutral process?—a qualitative study of the evaluation of research grant applications, Swedish Research Council 2014, Stockholm

Aksnes DW, Rorstad K, Piro F, Sivertsen G (2011) Are female researchers less cited? A large-scale study of Norwegian scientists. J Am Soc Inform Sci Technol 62(4):628–636

Baer J, Kaufman JC (2008) Gender differences in creativity. J Creat Behav 42(2):75–105

Bagilhole B, Goode J (2001) The contradiction of the myth of individual merit, and the reality of a patriarchal support system in academic careers. a feminist investigation. Eur J Women’s Stud 8(2):161–180

Bailyn L (2003) Academic careers and gender equity: lessons learned from MIT. Gend Work Organ 10(2):137–153

Baruch Y, Hall D (2004) The academic career: a model for future careers in other sectors. J Vocat Behav 64(2):241–262

Bird SR (1996) Welcome to the men’s club: homosociality and the maintenance of hegemonic masculinity. Gend Soc 10(2):120–132

Bleijenbergh IL, van Engen ML, Vinkenburg CJ (2012) Othering women: fluid images of the ideal academic. Equal Divers Incl 32(1):22–35

Brouns M, Addis E (2004) ‘Gender and excellence in the making’, synthesis report. European Commission, Luxembourg

Carnes M et al (2015) Effect of an intervention to break the gender bias habit for faculty at one institution: a cluster randomized, controlled trial. Acad Med 90(2):221–230

Castilla EJ (2008) Gender, race, and meritocracy in organizational careers. Am J Sociol 113(6):1479–1526

Castilla EJ, Benard S (2010) The paradox of meritocracy in organizations. Adm Sci Q 55(4):543–676

Correll SJ (2017) Reducing gender biases in modern workplaces: a small wins approach to organizational change. Gend Soc 31(6):725–750

Deem R (2009) Leading and managing contemporary UK universities: do excellence and meritocracy still prevail over diversity? High Educ Policy 22(1):3–17

DFF Danish Council for Independent Research (2016) Call for proposals, Autumn 2016 and Spring 2017

DFG Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (2016) Guidelines Emmy Noether programme

Diaz-Garcia MC, González Moreno A, Saez-Martinez FJ (2013) ‘Gender diversity within R&D teams: its impact on radicalness of innovation’, Innovation: management. Policy Pract 15(2):149–160

Durbin S (2011) Creating knowledge through networks: a gender perspective. Gend Work Organ 18(1):90–112

Eagly AH, Carli LL (2007) Through the labyrinth: the truth about how women become leaders. Harvard Business School Press, Boston

EC European Commission (2013) ERC work programme 2014

EC European Commission (2014) ERC rules for submission and evaluation

EC European Commission (2016) ERC work programme 2017

European Commission, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (2004) Gender and excellence in the making. Publications Office

Elg U, Jonnergård K (2003) The inclusion of female PhD students in academia: a case study of a Swedish university department. Gend Work Organ 10(2):154–174

Ellemers N et al (2004) The underrepresentation of women in science: differential commitment or the Queen-bee syndrome? Br J Soc Psychol 43(3):315–338

Elsevier (2017) The researcher journey through a gender lens—analysis of research performance through a gender lens

Ely RJ, Meyerson DE (2000) Theories of gender in organizations: a new approach to organizational analysis and change. Res Organ Behav 22:103–151

Ely R, Padavic I (2007) A feminist analysis of organizational research on sex differences. Acad Manage Rev 32(4):1121–1143

Etzkowitz H et al (1994) The paradox of critical mass for women. Science 266(5182):51–54

Ferree MM, Zippel K (2015) Gender equality in the age of academic capitalism: Cassandra and Pollyanna Interpret University restructuring. Soc Polit Int Stud Gend State Soc 22(4):561–584

Ferretti F et al (2018a) Research excellence indicators: time to reimagine the ‘making of’? Sci Public Policy 45(5):731–741

Ferretti F et al (2018b) Research excellence indicators: time to reimagine the ‘making of’? Sci Public Policy 45(5):732

Foschi M (2004) Blocking the use of gender-based double standards for competence. In: Brouns M, Addis E (eds) Gender and excellence in the making. European Commission, Brussels, pp 51–55

FWF Der Wissenschaftsfonds (2017) Application guidelines 2017 for the career development programme for women—Elise Richter

Geuna A (ed) (2015) Global mobility of research scientists—the economics of who goes where and why. Academic Press, London

Gherardi S, Poggio B (2001) Creating and recreating gender order in organizations. J World Bus 36(3):245–259

Girod S et al (2016) Reducing implicit gender leadership: bias in academic medicine with an educational intervention. Acad Med 91(8):1143–1150

Glaser B, Strauss A (1967) The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research, AldineTransaction, London

Haas M, Schiffbänker H (2016) (Do not) publish with your supervisor!"—the ambivalent construction of independence in a scientific career‘. In: STS conference sociotechnical environments, University of Trento, Italy

Haslam A (2004) Psychology in organisations: the social identity approach. Sage Publications, London

Hearn J, Husu L (2011) Understanding gender: some implications for science and technology. Interdisc Sci Rev 36(2):103–113

Heilman ME (2001) Description and prescription: how gender stereotypes prevent women’s ascent up the organizational ladder. J Soc Issues 57(4):657–674

Heilman ME, Manzi F, Braun S (2015) Presumed incompetent: perceived lack of fit and gender bias in recruitment and selection. In: Broadbridge AM, Fielden SL (eds) Handbook of gendered careers in management: getting in, getting on, getting out. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp 90–104

Herschberg C, Benschop Y, Van den Brink M (2015) Constructing excellence: the gap between formal and actual selection criteria for early career academics, GARCIA working papers, 2, Trento

Herschberg C, Benschop Y, Van den Brink M (2018) The peril of potential: gender practice in the recruitment and selection of early career researcher. In: Murgia A, Poggio B (eds) Gender and precarious research careers. Routledge, London

Husu L (2004) Gate-keeping, gender equality and scientific excellence. In: Brouns M, Addis E (eds) Gender and excellence in the making. European Commission, Brussels, pp 69–76

Joens H (2011) Transnational academic mobility and gender. Glob Soc Educ 9(2):183–209

Joshi A (2014) By whom and when is women’s expertise recognized? The interactive effects of gender and education in science and engineering teams. Adm Sci Q 59(2):202–239

Kanter RM (1977) Men and women of the corporation. BasicBooks, New York

Kelan E (2009) Performing gender at work. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Knights D, Richards W (2003) Sex discrimination in UK academia. Gend Work Organ 10(2):213–238

Lamont M (2009) How professors think: inside the curious world of academic judgment. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Langfeldt L (2004) Expert panels evaluating research: decision-making and sources of bias. Res Eval 13(1):51–62

LERU – League of European Research Universities. (2018) ‘Implicit bias in academia: a challenge to the meritocratic principle and to women’s careers—and what to do about it‘, Leuven

Martin PY (2003) “Said and done” versus “saying and doing”: gendering practices, practicing gender at work. Gend Soc 17(3):342–366

Martin PY (2006) Practising gender at work: further thoughts on reflexivity. Gend Work Organ 13(3):254–276

Morley L (2016) Troubling intra-actions: gender, neo-liberalism and research in the global academy. J Educ Policy 31(1):28–45

Moss-Racusin CA et al (2012) Science facultys subtle gender biases favor male students. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109(41):16474–16479

Nielsen MW (2015) Limits to meritocracy? Gender in academic recruitment and promotion processes. Sci Public Policy 43(3):386–399

Nielsen MW (2017) Gender consequences of a national performance-based funding model: new pieces in an old puzzle. Stud High Educ 42(6):1033–1055

NIH (2017) Postdoc-guide. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/grants-contracts/postdoc-guide. Accessed 11 Aug 2016

O’Connor P, O’Hagan C (2016) Excellence in university academic staff evaluation: a problematic reality? Stud High Educ 41(11):1943–1957

Paulus P (2000) Groups, teams, and creativity: the creative potential of idea-generating groups. Appl Psychol 49(2):237–262

Pecis L (2016) Doing and undoing gender in innovation. femininities and masculinities in innovation processes. Hum Relat 69(11):2117–2140

Pirola-Merlo A, Mann L (2004) The relationship between individual creativity and team creativity: aggregating across people and time. J Organ Behav 25(2):235–257

Poggio B (2006) Editorial: outline of a theory of gender practices. Gend Work Organ 13(3):225–233

Poggio B (2010) Vertical segregation and gender practices: perspectives of analysis and action. Gend Manage 25(6):428–437

Proudfoot D, Kay AC, Koval CZ (2015) A gender bias in the attribution of creativity: archival and experimental evidence for the perceived association between masculinity and creative thinking. Psychol Sci 26(11):1751–1761

Rees T (2011) The gendered construction of scientific excellence. Interdisc Sci Rev 36(2):133–145

Rhoton LA (2011) Distancing as a gendered barrier. understanding women scientists. Gend Pract Gend & Soc 25(6):696–716

Sabatier M, Carrère M, Mangematin V (2006) Profiles of academic activities and careers: does gender matter? An analysis based on french life scientist CVs. J Technol Transf 31(3):311–324

Schaubroeck J, Lam SSK (2002) How similarity to peers and supervisor influences organisational advancement in different cultures. Acad Manage J 45(6):1120–1136

Schiebinger L (2000) Has feminism changed science? Signs: Fem Millenn 25(4):1171–1175

Schiffbänker H, Holzinger F (2016) Indicators for constructing scientific excellence: ‘independence’ in the ERC Starting Grant. In: Conference, 21st international conference on science and technology indicators, Valencia, Spain

Shauman KA, Xie Y (1996) Geographic mobility of scientists: sex differences and family constraints. Demography 33(4):455–468

Slaughter S, Leslie LL (2001) Expanding and elaborating the concept of academic capitalism. Organization 8(2):154–161

Sørensen MP, Bloch C, Young M (2016a) Excellence in the knowledge-based economy: from scientific to research excellence. Eur J High Educ 6(3):217–236

Sørensen MP, Bloch C, Young M (2016b) Excellence in the knowledge-based economy: from scientific to research excellence. Eur J High Educ 6(3):219

Steinthorsdóttir FS et al (2019) New managerialism in the academy: gender bias and precarity. Gend Work Organ 26(2):124–139

Stilgoe J (2014) ‘Against excellence’, the guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/science/political-science/2014/dec/19/against-excellence. Accessed 08 Sept 2022

Uhly KM, Visser LM, Zippel KS (2015) Gendered patterns in international research collaborations in academia. Stud High Educ 42(4):760–782

Van Anders SM (2004) Why the academic pipeline leaks: fewer men than women percieve barriers to becoming professors. Sex Roles 51(9):511–521

Van Emmerick H (2006) Gender differences in the creation of different types of social capital: a multilevel study. Soc Netw 28(1):24–37

Van Knippenberg D, De Dreu C, Homan A (2004) Work group diversity and group performance: an integrative model and research agenda. J Appl Psychol 89(6):1008–1022

Van den Brink M (2010) ‘Behind the scenes of science: gender practices in the recruitment and selection of professors in the Netherlands‘. Pallas Publications, Amsterdam

Van den Brink M, Benschop Y (2012) Gender practices in the construction of academic excellence: sheep with five legs. Organization 19(4):507–524

Van den Brink M, Benschop Y (2013) ‘Gender in academic networking: the role of gatekeepers in professorial recruitment‘. J Manage Stud 51(3):460–492

Van den Brink M, Benschop Y (2014) Gender in academic networking: the role of gatekeepers in professional recruitment. J Manage Stud 51(3):460–492

Van den Besselaar P, Sandström U, Van der Weijden I (2012) The independence indicator. In: Archambault E, Gingras Y, Lariviere V (eds) Science & technology indicators 2012. OST & Science Metrix, Montreal, pp 131–141

Van den Brink M, Brouns M, Waslander S (2006) Does excellence have a gender?: A national research study on recruitment and selection procedures for professorial appointments in The Netherlands. Empl Relat 28(6):523–539

Walby S (2011) Is the knowledge society gendered? Gend Work Organ 18(1):1–29

Wennerås C, Wold A (1997) Nepotism and sexism in peer-review. Nature 387(6631):341–343

Wroblewski A (2014) Gender bias in appointment procedures for full professors: challenges to changing traditional and seemingly gender neutral practices. In: Demos V, Berheide CW, Segal MT (eds) Gender transformation in the academy. Advances in gender research, 19. Emerald, Bingley, pp 291–313

Xie Y, Shauman KA (2003) Women in science: career processes and outcomes. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Zippel K (2018) Gendered images of international research collaboration. Gend Work Organ 26:1794–1805

Acknowledgements

The paper is based on the the project GendERC (2014–2016), Grant Number: 610706, commissioned by the ERC/EC.

Funding

Open access funding provided by JOANNEUM RESEARCH Forschungsgesellschaft mbH. HS: research was funded from 2014 to 2016 in FP7 by European Research Council (ERC), Grant Agreement No. 610706.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HS and MH: conception and design. HS and FH: collection of research data, analysis of research data. HS, MH and FH: interpretation of anonymized research data, drafting and revising the manuscript, approving the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest