Abstract

The aim of this exploratory study is to provide a better understanding of the representation shared by Chinese teenagers in Italy about Italian people. As research into migrants’ attitudes toward the host culture and society is rare, this study aims to bridge this gap. In 2016, 22 low-income first and second-generation Chinese teenagers living in an Italian city were interviewed. Analysis of their narratives, performed with T-Lab, a text mining software, produced three thematic clusters: “value differences”, the most relevant, which highlights the contrast between the perceived Chinese ethics of sacrifice versus the Italian propensity for leisure; “peer relationships and school life” which points at difficulties and opportunities in the integration process; while in the “stereotypes and prejudices” cluster, a kaleidoscopic vision of others as enemies emerges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The interest of the present research is part of the classic topic of social psychology on intergroup relations and how these are often biased by stereotyped and discriminatory representations, which can lead to the emergence of conflicts between members of different social groups. Theories on intergroup contact have indeed shown how this contact can on one side lead to the perception of intergroup threat, on the other to the reduction of prejudicial attitudes (Pettigrew et al. 2011). The success or failure of contact interactions in decreasing intergroup conflict depends on several elements, one of which is the individual and collective representations shared by members of the in-group regarding the out-group (Dovidio et al. 2003). Most studies that have analyzed intergroup relations have primarily focused on the attitudes of host country members (in-group) toward immigrant members (out-group). The novelty of the present study is to study the inverse, i.e., the representations of immigrants of their host society. Indeed, in-group and out-group representations and their positive or negative connotations are crucial as they affect the integration process of migrants in the host country and intergroup relations in general in the short- and long-term (Reicher et al. 2008). While the focus has often been on only one side of the coin, it therefore becomes important to analyze integration as a two-way process, so that if the host society's perception of immigrants is important, so are the perceptions that immigrants have (Gonzales and Brown 2017). Specifically, the present research focuses on the representations shared by immigrant teenagers, with the idea, widely supported in the literature (Phinney 1990), that this is an important and critical period in the formation of their cultural identity and integration in the host country. In the following paragraph, some more information about the social group under investigation will be outlined. After that, the main theories that analyzed the topic of intergroup contact and the one of acculturation in adolescence will be concisely presented.

Chinese migrants in Italy

The number of Chinese migrants in Italy has been steadily growing. The Chinese population, which has grown from 209,000 in 2011 to 288,923 in 2020 (Statistiche Tuttitalia 2021b), represents the third largest minority in the country (Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali 2018). Most Chinese migrants come from the Wenzhou and Qingtian areas of the Zhejiang Province and display a number of similarities, such as low socio-economic background, low levels of education, aspirations of owning a family business, and poor integration in the host society (Latham and Wu 2013). The Chinese community in Italy is relatively young: its median age is lower than that of other non-EU citizens living in Italy (Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali 2018). Children make up about 26% of the community, 2 percentage points more than other non-EU citizens (Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali 2018). 30% of the student population in Italy is foreign; China ranks fourth (41,707 students) (Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca 2015). Chinese teenagers’ life is greatly affected by the importance of the family business. Firstly, since parents very often work overtime, they have less time to meet their children’s emotional and psychological needs (Sáiz López 2015). Also, Chinese teenagers are usually required to help in the family business and are even asked to be interpreters or mediators with host society members (Chung 2013). Chinese communities in Italy rest upon a family based migratory model and independent enterprises, which thrive on close-knit relationships. Members of these communities, mainly established in larger cities, tend to stress the importance of their cultural heritage (Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali 2018). In early research on the Chinese in Europe, Pieke (1988) highlighted the relative invisibility of Chinese migrants. Thirty years later, Italian media perpetuates the perception of the Chinese community as closed and attached to its traditions (Latham 2015).

Theoretical framework

The question of whether or not contact between different social groups within the same context can foster tolerance between members of those groups, and when such interactions instead support intergroup conflict, has been a central topic in social psychology since Allport’s (1954) seminal work (Dovidio et al. 2003). This question has become topical again in recent decades, following the great migratory movements that have involved the so-called Western countries as a destination (Passini and Villano 2018). Recent studies (see Pettigrew et al. 2011) have shown, in particular, that in order to prevent attitudes and behaviors of discrimination, it is necessary to analyze the representations of members of the in-group with regard to those of the out-group, and vice versa, in order to consider when these are vitiated by stereotyped images. While the literature is in broad agreement about the positive effects of intergroup contact (Lytle 2018), these can be undermined by interacting according to stereotypical representations that increase the “us” vs. “them” perception. As Gonzales and Brown (2017) have pointed out, most of the literature on intergroup contact focuses on how contact affects the attitudes, perceptions, and behavior of the majority, with much smaller literature examining the same variables on minority individuals. Specifically, the two authors suggest the need to better understand how climate and social norms may influence acculturation preferences and how this may foster positive intergroup contact through increased intergroup trust and perceived similarities to the other group (Lytle 2018). Moreover, the possibility that the socio-political context may influence the way in which members of two different groups interact with each other should also not be underestimated (Pertiwi et al. 2020). These considerations about the outcome of intergroup contact and the actions that can be taken to foster positive relationships take on even greater importance wherever the two cultures that come into contact appear to differ significantly with respect to the vision of society itself. In particular, people who migrate from collectivist to individualistic societies (Triandis 2001), from high-power-distance to low-power-distance societies (Hofstede et al. 2010), from long-term to short-term orientation societies (Hofstede and Minkov 2010), undergo a more arduous acculturation process (Berry et al. 2002). Some studies (see Cheng et al. 2020) have actually shown that immigrants from collectivist societies have more difficulty in making friends and experience negative events more often in the process of integrating into an individualist society than immigrants from individualist societies.

The issue of acculturation and the impact of ethnic identities on intergroup contact acquire particular relevance when considering migrants going through adolescence, a stage of identity formation (Crocetti, Fermani, Pojaghi and Meeus, 2011). Migrants, especially teen-agers, experience difficulties during the adaptation process (Aronowitz 1984, 1992; Carlin 1990; Ghuman 1991; Sam and Berry 1995), not only the age-related identity-building struggle, but also all the difficulties and uncertainties that come with the migrant status and the acculturation process. Consequently, the evolutionary challenges distinctive of this age group create additional stress factors (Crocetti et al. 2011). Migrant teenagers are forced to deal with a larger set of values and norms, deriving from both their family traditions and the hosting society (Berry 2001). One’s own culture and society usually provide teenagers with a sense of belonging and safety. On the other hand, being a migrant changes the perception of the environment and deprives one of any point of reference (Phinney 1990).

European and American research offers an overview of the psychological difficulties experienced by migrants (see e.g., Sam et al. 2008; Mannarini et al. 2018; Robles-Llana 2018; Stein et al. 2018). However, psychological research on Asian immigrants in Western societies has focused primarily on the experiences of college students, middle and upper-class populations, and participants who are at least second-generation migrants, while little research exists on Asian immigrant teenagers, especially among low-income populations (Yeh et al. 2008). The academic and professional achievements of a great many Asian Americans has fuelled the “model minority” myth (Kao 1995, 1999; Lee 1996). However, many Asian Americans and Asian immigrants experience poverty, school dropout, generational conflict, and psychological distress (Yeh et al. 2008). The well-documented low utilization of mental health services by Asian Americans due to cultural values such as avoidance of shame and stigma further perpetuates the notion that this group suffers fewer psychological problems (NAMI 2011). Consequently, there is a need to explore the experiences of children of migrants of different ages in different socio-cultural and geographical contexts in order to bring forth new analytical categories that address their specificities (Robles-Llana 2018; Cao et al. 2018).

Literature on the Chinese living in Italy is limited, with some exceptions (see e.g., Cologna 2005; Pedone 2011; Barbieri and Zani 2015; Ottati and Cologna 2015) to the national research audience, and published mainly in Italian (Ceccagno 1999; Cologna 2002, 2009; Cologna and Breveglieri 2003; Pedone 2004, 2008). Moreover, most of the literature regarding the migrants living in Italy is focused on discrimination (see e.g., Cariota Ferrara and La Barbera 2008; Pivetti et al. 2018) and the attitudes (see e.g., Castellini et al. 2011) of the host society toward them. Few studies, on the other hand, focus on the representation of Chinese immigrants of their host society and how it affects their experience.

Minorities, which are often victims of stereotyping, possess their own cultural baggage, in other terms, they tend to categorize and build representations of the groups among which they live. Research regarding the attitudes of migrants toward the receiving culture and society, their interpersonal and intergroup relationships is extremely rare and this study aims to bridge this gap. It focused on the following research questions: (a) How do the participants perceive Italians, their culture (b) and their relationships with them? (c) Do these perceptions evolve as individuals become more familiar with the host culture?

Method

Participants

In a study on the Chinese community in Italy, Nielsen et al. (2012) underline the need to conduct in-depth interviews in order to gain some insight in the experience of Chinese migrants in Italy. In accordance with these considerations, we have conducted interviews with teenagers aimed at exploring their experience in Italy. For this semi-structured study, not based on a priori research hypotheses, in-depth interviews with 22 teenagers were conducted in Chinese between April and May 2016. This study was conducted in San Benedetto del Tronto, a town in central Italy with a population of approximately 49,000 and an estimated 149 Chinese citizens (Statistiche tuttitalia 2021a). Four public high schools in San Benedetto del Tronto were involved in the study. Specifically, teachers contacted the families of all enrolled Chinese students to ask for consent to be interviewed. Participants in the study were those who agreed to be interviewed in the local public library.

The participants were 16 female and 6 male students between 14 and 18 years of age, all permanent residents who migrated to Italy with their parents and belong to low-income households. Six of them were second-generation Chinese, 16 of them had been in Italy for 2–12 years (first-generation). Only six of them experienced a linear migration process (see Table 1), which consists in migrating only once. Children born in Italy are sometimes sent back to China at birth or within their first year of age by parents who are unable to look after them, and later return to rejoin them, when they reach school age or later. Furthermore, due to the work demands of their parents, the majority of non-linear migration process participants have lived in several Italian or European cities.

Both participant and parental consent were obtained prior to the interviews. The participants were informed that they would remain anonymous and that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any stage. No economic incentive was offered. Each participant was interviewed individually for approximately one hour.

The interviews were conducted by one of the authors, who works as an intercultural mediator in hospitals in the area of San Benedetto del Tronto. She speaks Chinese and is considered to be a trusted insider (Merton 1972) in the local Chinese community. Her participation was crucial in overcoming the language barrier which often impedes research on the Chinese community in Italy (Nielsen et al. 2012). As suggested by Xing (2001), the presence of the trusted insider as interviewer made the participants more willing to overcome their reticence and share their thoughts (Fang et al. 2016). The concept of “face” (mianzi), crucial in Chinese culture, refers to a person’s reputation and feelings of prestige which permeate all aspects of life (Lockett 1988). Due to the familiarity with the interviewer, the participants felt at ease expressing negative opinions and feelings about the host society not fearing the interviewer’s “loss of face”, in other words, her feeling offended. This allowed for emotionally richer interviews, and therefore semantically richer contents, which provide for more significant analysis.

The interviews addressed four topics: their migratory path, their relationship with Italians, their opinions of Italians and how they believe Italians perceive them. The first section includes questions about their migration process, their plans for the future, and their wish to remain in Italy. The second area of investigation concerns their school life and the relationships with their Italian classmates. The opinions expressed by the participants on Italian people, values and lifestyle are the central theme of the third section. The last part of the interview regarded potential relationships between the Italians and the Chinese. The questions addressed what Chinese believe Italians might think of them, and what forms of intolerance they have suffered. All the interviews were conducted, recorded and transcribed in Chinese and then translated into Italian.

Data analysis

The interviews were organized into a corpus and analysed using the T-LAB text mining software, within a qualitative research paradigm (Jodelet 2003). This qualitative approach unveils subjective experiences that are socially built and context-bound. Through language, we can explore cognitive and affective representations which characterize the participants’ experience and are shared in that context. This software allows in fact to identify shared latent themes or issues associated with the topics being researched (Braun and Clarke 2006) across the entire data set.

From an operational point of view, the interviewer’s questions were omitted as well as empty words (e.g., articles, conjunctions, prepositions), and lemmatization was carried out (i.e., grouping of inflected forms into single lemmas that can be analysed as single items) (Verrocchio et al. 2012; Cortini and Tria 2014). After lemmatization, the researchers choose the main keywords within the list (provided by the software) in line with their research aim and build a dictionary. Each interview was labelled according to the set of variables selected for this study: age group, gender, generation status, migration path and Italian language proficiency (basic, intermediate, fluent).

T-LAB builds a representation of the whole corpus through few and significant thematic clusters, each of which consists of a set of elementary context units (ECUs, i.e., sentences, paragraphs or short texts like responses to open-ended questions) characterized by the same patterns of keyword (Lancia 2012). Co-occurrences analysis shows the frequencies of two or more keywords in the same elementary context by transforming the corpus into a presence/absence matrix, in which each row consists of an “elementary context unit”, and each column consists of lexical units (i.e., keywords that reach a given frequency threshold).

A comparative analysis is then performed. A contingency table is built of lexical units by clusters—derived from the co-occurrence analysis; a chi squared test is then applied to the intersections of the table. The test reveals groupings of words co-occurring in the same ECUs with the highest probability; these thematic clusters are then appropriately labelled by the researchers based on the most characteristic lexical units provided. These thematic clusters shed light on the associations that arise on a psychological level in the participants, and in particular on the way a theme might be cognitively and emotionally conceptualized.

Finally, T-Lab carries out a correspondence analysis of the contingency table, which determines a spatial relationship between clusters and variables, and points at the main factors underlying the semantic oppositions in the corpus. This produces a graphical representation of the whole universe of meanings evoked by the participants (the “factorial space”). This factorial space is defined by a number of bipolar factors, characterized by opposite processes of meaning. Total variation is divided into components along axes, each representing a factor (labelled by the researcher), defined by polar opposites so that variables and clusters on opposite poles are the most weakly associated. Factor 1 (x-axis) accounts for the maximum variation, Factor 2 (y-axis) accounts for the maximum of the remaining variation. A framework of interpretation is thus provided. The T-LAB analysis was carried out by one of the authors, an expert in T-Lab qualitative research (Author et al. 2018, 2019). The output was interpreted separately by each of the authors with the aim to interpret the sense-making process from a psychosocial point of view (Markova, Linell, Grossen and Orvig 2007).

Results

Thematic analysis

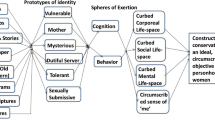

The analysis of the interviews with the T-LAB software produced three clusters (see Table 1) represented across two dimensions (see Fig. 1).

Cluster 2: “Value differences”

Cluster 2, labelled “value differences” is the most relevant. It includes 56.66% of the ECUs. The most frequent keywords (ranked by χ2) were: money (13.63), family (13.59), work (13.29), we (12.98), different (9.79), parent (8.92), ours (8.45), future generations (7), Italians (6.57), open minded (6.21), earning money (6.12), care taking (6.12), tradition (6.09).

The participants seem to perceive a culture gap between the Chinese, who value strong family ties and honour generational hierarchy, and the Italians, who do not. More significantly, according to the participants, while the former are busy accumulating wealth, to ensure long-term livelihood, the latter focus more on their present lifestyles and the enjoyment of short-lived pleasures. In essence, Italians are seen like the irresponsible, carefree and lazy grasshopper portrayed in Aesop’s fable “The Grasshopper and the Ant” while the industrious and provident Chinese are not unlike the ant.Footnote 1

The following are some of the ECUs in which keywords co-occur and have contributed to cluster formation.

We usually say that Italians are good at enjoying life. They are not like the hard-working Chinese, who even send family members to different parts of the world to make money.

(a first-generation 16-year-old male)

The interviewees consider money the most important way to take care of the family and support future generations.

My mother has already saved enough money for us and for herself, but she still strives for more money in compliance with Chinese tradition. We all know that the Chinese work, work and work to make money because in our tradition to earn money and save for future generations is crucial.

(a firstgeneration 14-year-old female)

Participants seem to deplore the lack of moral standards in Italian society (i.e., tradition), and particularly the “carefree attitude” of Italians, insufficiently concerned with the welfare of their family.

The Chinese like money, especially saving it, Italians as soon as they have money in their hands, they squander it. It is a very different way of thinking, the Chinese think about future generations, while Italians waste their time.

(a first-generation 14-year-old female)

And:

When they make money, Italians spend it right away, because unlike the Chinese they don't care about future generations. The Chinese buy cars and houses for their children. Spending all this money makes no sense. In August, when they go to the beach, Italians spend all the money that they managed to save. They like to enjoy life.

(a first-generation 16-year-old female)

According to the participants, their parents as well express rather negative views about Italian values.

At home we talk about the Italians, my parents say that they waste their time and they don't know how to manage their money. My parents think that Italians are irresponsible, that they don't think about future generations. But the way I see it, their life is easier than ours because they’re not obsessed with money.

(a second-generation 14-year-old female)

Cluster 3: “Peer relationships and school life”

Cluster 3 is the second most relevant theme which emerged from the interviews. The cluster mainly refers to the experience of the participants at school and their relationships with their Italian classmates and teachers. The most frequent keywords and phrases ranked by χ2 are: school (48.44), classmate (44.97), homework (15.93), Italian friend (29.59), Facebook (21.64), teacher (20.90), student (11.71), afternoon (10.59), meeting (Italian friends; 10.08), pressure (19.40) and discrimination (19.23).

The participants are ambivalent about their school life. On the one hand, compared to China, school in Italy is far less demanding. On the other, peer relationships appear to be less than satisfying, as they are hindered by prejudice, according to the participants, who also spoke of episodes of discrimination. Teachers, however, are seen as supportive and sympathetic.

The following are some of the ECUs (in italics) in which keywords co-occur and have contributed to cluster formation.

Maybe the reason why we're not good friends with my classmates is because my Italian isn't good enough. We met at school and when we're together we do our homework, but I hardly ever meet them in the afternoon.

(a first-generation 18-year-old female)

School in China is difficult, you’re always studying, there are few breaks and you have to go in the afternoon too. In Italy school is easy, you go only in the morning, the teachers are nice, but my classmates completely ignore me and this makes me feel very lonely.

(a first-generation 17-year-old male)

Teachers are understanding, but my classmates make fun of me because I don't speak much or because I sleep in class sometimes. Italian kids have an easy life, they don't have to work or help their parents. I sleep in class because I work in the afternoon and in the evening, so when I get to school, I am tired, yet I cannot but help my parents, if you can call them that...

(a first-generation 17-year-old male)

Classmates often say bad things about the Chinese behind their backs. School in China was much more difficult, [we had] much more homework, much more pressure, I was forced to go, in Italy I can even stay at home and sleep if I don't feel like going.

(a first-generation 18-year-old female)

Cluster 1: “Stereotypes and prejudices”

Cluster 1 “stereotypes and prejudices”, which accounts only for 8.32% of the ECUs, is the smallest cluster. It refers to attitudes held by the Chinese toward the Italians and how they feel about the latter’s opinion regarding them. Overall, Chinese teen-agers express negative views towards Italians and acknowledge some negative views expressed by Italians towards the Chinese community. Keywords of the cluster include (ranked by χ2): “complaining” (160.77), “dirty” (72.99), “sly” (47.44), “food” (29.11), “poor quality products” (20.60), “Italians-Waiguoren” (13.44), “Chinese” (11.31), “stealing” (10.32), “eating dogs” (6.10). Ranked high above all other terms, the word “complaining” refers to the Italians’ attitude toward life. Italians are considered reluctant to take action and oblivious to everything except the enjoyment of life.

Italians can speak all day about something without doing anything about it: they are inconclusive! They are lazy and slow. Italians complain for hours about things they should not without resolving them. They talk a lot, but they do not do much (...) We Chinese believe that it is pointless complaining: for example, students complain that teachers do not teach well, but in reality, they are not listening and therefore do not understand. They also blame others for their mistakes and have bad habits.

(a first-generation 17-year-old female)

Some Italians are sly, they act all nice in your presence but then they backstab you, they're turncoats... Italy is a country of complainers. Italians complain about everything and they complain a lot about the Chinese for everything they do. The worst thing is that Italians complain all the time but they do nothing to change things.

(a first-generation 17-year-old female)

Furthermore, participants usually do not speak about Italians at home or with their parents and they only mention them when describing discriminatory episodes and problems they have had.

At home we barely talk about Italians. My parents believe Italians are all ignorant. They just know how to complain about their country and the crisis, but do nothing concrete to improve the situation. That is why they avoid contact with the Italians.

(a second-generation 17-year-old male)

Participants also have a profoundly negative perception of the Italian views towards them. Chinese participants feel they are treated as members of an ethnic category rather than as people, and are victims of generalization. They believe Italians see them as dirty, sly, and dog-eaters, manufacturers and sellers of poor-quality products who steal their jobs and money.

Italians complain that Chinese people are dirty, because they don’t clean the apartments they rent when they move out. They complain that our cooking smells. Then Italians whine that we Chinese have iPhones, and therefore we are richer. Perhaps we are, but our wealth is based on huge sacrifices.

(a second-generation 14-year-old female)

The factorial plane and the variables

The factorial plane represents the whole field of discourse. It is a graph where the axis represents two factors, each of which is defined by polar opposites. The analysis produced two factors: Factor 1, the horizontal one, which expresses an opposition between “interpersonal” (on the negative pole) and “intergroup relationships” (on the positive one) (Tajfel 1981), and Factor 2, the vertical factor, defined by “abstract values and principles” on the negative pole, which refers to one’s cultural heritage and choices in matters of education, politics, religion and lifestyle, and “daily behaviour” on the positive pole, which refers to one’s choices in the areas of friendship, dating, gender roles, and recreation.

Clusters are placed within the factorial plane. The logic behind the construction of the cluster is that they are formed so as to be as homogeneous as possible within them and maximally diversified from each other. However, they all come from the common matrix of the discourse and thus are interconnected on the factorial plane.

In particular, the “peer relationship and school life” cluster (n.3) is linked to the “interpersonal relationships” pole of Factor 1. We can interpret this association as evidence that, for the participants, interpersonal relationships with the host society are mainly possible at school. The polar opposite, “intergroup relationships” is instead associated with the “value differences” (n.2) and “stereotypes and prejudices” (n.1) clusters: as a matter of fact, differences in terms of values, as well as prejudices and stereotypes are experienced mainly at the intergroup level. In other terms, for these participants, intergroup relationships are defined in terms mainly of the value differences that exist between the Chinese and the Italians, and, to a lesser extent, in terms of mutual stereotypes and prejudices which may characterize daily situations.

Both sharing the positive pole “intergroup relationship” on the first factor, on the second factor, “value difference "cluster (n.2) is placed near the negative pole (“abstract rules and principles”), represented by cultural heritage, while the “stereotypes and prejudices” cluster (n.1) is at the opposite positive pole called “daily behaviour”, characterized by friendship and recreation.

Data also shows that, among the structural variables taken into consideration (age group, gender, generation status, migration path and Italian language proficiency), generation status and language proficiency are most significant, whereas the other variables lie at the intersection of the two factorial axes, which means they are common to the entire factorial plane, thus not specific to any subgroup.

Highly proficient second-generation Chinese teenagers lie in the lower left quadrant of the factorial plane, where the polarity of Factor 1 “interpersonal relationship” and of Factor 2 “abstract rules and principles” intersect. Second-generation Chinese immigrants appear to be the most conflicted: on the one hand, their command of the Italian language should facilitate their interaction with the host society on an interpersonal level; on the other hand, their awareness of the culture gap somewhat hinders it. In other words, it seems that the longer Chinese teen-agers have been living in Italy and have been socializing with Italians, the more they perceive the distance with the target culture.

First-generation participants who have been living in Italy for less time and have low language proficiency lie in the upper right quadrant of the factorial plane, at the intersection of the “intergroup relationship” pole of Factor 1 and the “daily behaviour” pole of Factor 2. Low proficiency severely limits interpersonal relationships, this is why, for first-generation migrants, relationships are almost exclusively intergroup.

Discussion

Based on the literature that has investigated the issue of intergroup contact, the aim of the present research was to investigate the perceptions and attitudes of migrant teen-agers towards the host country. Specifically, as concerns our first two research questions (i.e., how participants perceive Italian culture and their relationship with native people), what emerged is how the relationship between the two groups is experienced as vitiated by stereotypes and prejudices, both expressed and experienced by the teen-agers interviewed. Specifically, Cluster 2 “value differences” can be explained in terms of the vast difference between collectivist and individualistic societies. According to Hofstede (2019), the individualism/collectivism polarity depends on whether self-image is defined in terms of “I” or “We”. Indeed, our participants spoke about themselves as Chinese rather than as individuals and exhibited a sense of belonging using terms such as “we” and “ours”. This cluster shows that individualistic behaviour, typical of Western culture, is usually considered selfish, shameful and socially damaging versus the virtuous accumulation of wealth as means to ensure the material well-being of future generations. The results thus support the idea of greater distance occurring when intergroup relations take place between different cultures in terms of the individualism-collectivism axis. The factorial plan shows how a distance at the intergroup level is perceived by Chinese adolescents precisely in relation to classic themes that distinguish so-called collectivist cultures (like China) from individualist ones (Italy, in this case): greater importance is given by the former to the matters of tradition, family, and long-term plans, as opposed to a lack of moral standards and greater hedonism in Italian society peers. While this remains an assumption that cannot be inferred from the data collected, we can suppose that the participants feel even more difficulty in their integration process, precisely because of the differences in terms of shared values. That is, a tension emerges between the two cultural backgrounds that is well illustrated by the metaphor of the Grasshopper and the Ant. Given that migrants socialize in two social worlds—their own ethnic community and mainstream society—teenagers struggle to balance contrasting cultural systems. A study on international Chinese students in Belgium carried out by Cao et al. (2017) found that separation and integration were the most common acculturation strategies, both of which imply the tendency to maintain one’s cultural heritage. Ethnic separation grants a “comfort zone” in order to perpetuate the group’s cultural identity (Xing 2001).

Moreover, participants have a negative perception of the Italian society as shown by Cluster 1, “stereotypes and prejudices”. Relationships with Italians are perceived mainly in terms of in-group and out-group. According to McGuire and McGuire (1981), social identities are notable if they are distinctive in an individual’s social context. Being part of a specific minority within a group setting makes this membership noticeable and increases social identity prominence. Ethnic minority children spontaneously mention their ethnicity more often when they are merely asked to describe themselves (Yang et al. 2008). When referring to the Italians, most of the participants frequently use the term waiguoren, “foreigner”, which literally means “out-country person”. Beltrán and López (2001) have denoted in Chinese mentality, in China and elsewhere alike, a distinction between the outside (wai) and the inside (nei), whereby outsiders are viewed as dangerous and hostile, whereas insiders are considered trustworthy. The use of the term waiguoren and Chinese self-identification denotes that our participants seem to interact with Italians in terms of their group membership and identification (Tajfel 1979).

In addition, as concerns the third research question (i.e., a positive evolution of integration over time), our results oppose the idea that socio-cultural adaptation increases with time as individuals become more familiar with the host culture. It is expected that second-generation immigrants adapt more easily as opposed to the first-generation. Our study underlines an aspect of the “immigrant paradox” (Sam et al. 2008): first-generation immigrants often have higher levels of adaptation than the second-generation. Other research suggests that the views of Chinese adults in the U.S. and Chinese students in Germany becomes less favourable the longer they live in the host society (Chae and Foley 2010; Stein et al. 2018).

With regard to Cluster 3, views on school life are ambivalent: on the one hand, participants appreciate the fact that school in Italy is not as demanding as in China and express positive views towards their teachers; on the other hand, some suffer isolation and deplore that they are victims of discrimination on behalf of their peers. Along with scholars who consider the impact of the racial climate on individual acculturation experiences (Concepcion et al. 2013), our findings may also be explained and linked to this phenomenon. In fact, racist incidents in Italy have been rising over the past 2 years. In March 2018, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights deplored the racism and xenophobia in Italy’s election campaign (Human Rights Watch 2019). Chinese students, however, have a positive attitude towards their teachers (see Cluster 3 “peer relationships and school life”), by whom they feel looked after. Moreover, our results are in line with Troop and Pettigrew’s meta-analysis (2005), according to which, because the minority expects prejudice from the majority, positive interpersonal contact with members of the majority does not imply a group attitude shift. In fact, the second-generation Chinese teenagers in our study, who have socialized more with Italians, show minimal attitude change, as displayed in Fig. 1 “Clusters on the Factorial Plane”. Therefore, in relation to our third research question “Do these perceptions evolve as individuals become more familiar with the host culture?,” results show that, unlike what Allport (1954) predicted (at least in the first version of the contact hypothesis), there is no improvement in perceptions. This is a further confirmation of what Allport himself pointed out later about the conditions and the concrete possibilities in which contact supports positive interactions.

Conclusion

This study provides an exploratory understanding of the representations of Chinese teenagers living in Italy and sheds new light into their experience within their host society. An analogy can be drawn between the way Chinese teenagers, both first and second-generation, perceive the culture gap that separates them from their host society, and Aesop’s fable “The Ant and the Grasshopper”: while they belong to a culture that values hard work, self-sacrifice and providence, Italians are perceived as the exact opposite. According to the participants, they are prone to complaints and criticism, and view the Chinese as backward, as highlighted by racist incidents at school.

Interestingly, the participants’ ambivalence was manifest throughout this study. On the one hand, although they express negative views towards the Italians, they acknowledge their teachers’ support; moreover, there are aspects of their daily lives that they do enjoy: for example, academic pressure—perhaps even social pressure—would be far greater in China. On the other hand, they are conflicted between the sense of belonging to a group and the safety it provides as opposed to their desire to be acknowledged as individuals.

Finally, the results of the interview analysis showed that for ethnic and cultural integration, intergroup contact is by no means enough. Despite the robust findings on the contact effect, several issues still need to be addressed: one of these is the possibility that the socio-political context around individuals influences the way members of two different groups interact with each other. The fate of the minority Chinese community has taken very different trajectories among countries. For instance, in the U.S., Chinese Americans, who were previously viewed as less powerful within the country, have seen their status elevated. Although the stereotype of the Asian-American continues to carry with it some negative traits, the positive traits in relation to the “model minority” grant this group more equivalent respect and social status from the majority and other minority groups in society. The same cannot be said for Italy.

Limitations

This study was carried out on a small convenience sample: the participants were few in number and all lived in the same town. Chinese students in larger cities might display different representations and attitudes. Secondly, this study lacks longitudinal data which would significantly deepen our understanding of the identity-building process of Chinese teenage migrants.

However, we believe that our qualitative investigation might provide a fresh perspective into the representations of Chinese teenage migrants and a meaningful contribution to the debate on acculturation.

Data availability

Further data are in supplementary material file and are available on request from the corresponding author.

Notes

Aesop’s fable is about a grasshopper that spent the summer singing and dancing whereas the ant toiled away to stockpile food for the winter. When winter came, the grasshopper found itself starving and begged the ant to give it some food to eat. Instead, the ant rebuffs her for her laziness and tells her sarcastically to dance the winter away now. Despite an alternative version, also attributed to Aesop, in which the ant was seen as setting a bad example, the story was used to teach the virtues of hard work and the dangers of idleness. Thus, th.e fable only partially captures the way the Chinese view Italians, as the separation between virtues and vices it expresses is clear, without the ambivalence that characterizes the attitude of the interviewees.

References

Allport GW (1954) The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley Pub. Co, Cambridge

Aronowitz M (1984) The social and emotional adjustment of immigrant children. Int Migr Rev 26:89–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/019791839202600105

Aronowitz M (1992) Adjustment of immigrant children as a function of parental attitudes to change. Int Migr Rev 26:86–110. https://doi.org/10.2307/2546938

Potì S, Emiliani F, Palareti L (2018) Subjective experience of illness among adolescents and young adults with diabetes: a qualitative research study. J Patient Exp 5(2):140–146

Potì S, Palareti L, Cassis, FR, Brondi S. (2019) Health care professionals dealing with hemophilia: insights from the international qualitative study of the HERO initiative.J Multidiscip Healthc 12:361–375.https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S201759

Barbieri I, Zani B (2015) Multiple sense of community, identity and wellbeing in a context of multiculture: a mediation model. Community Psychol Glob Perspect 2:20–40

Beltrán AJ, López AS (2001) Elsxinesos a Catalunya: Familia, educació i integració. Alta Fulla/Fundació Jaume Bofill, Barcelona

Berry J (2001) A psychology of immigration. J Soc Issues 57:615–631. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00231

Berry J, Poortinga Y, Segall M, Dasen P (2002) Cross-cultural psychology: research and applications. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Cao C, Zhu C, Meng Q (2017) Predicting Chinese International Students’ Acculturation strategies from socio-demographic variables and social ties. Asian J Soc Psychol 20:85–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12171

Cao C, Meng Q, Shang L (2018) How can Chinese International Students’ host-national contact contribute to social connectedness, social support and reduced prejudice in the Mainstream Society? Testing a moderated mediation model. Int J Intercult Relat 63:43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.12.002

Cariota Ferrara P, La Barbera F (2008) September. L’effetto del conflitto realistico su pregiudizio sottile e manifesto: Il caso cinese. Paper presented at the Meeting “Spazi interculturali: trame, percorsi, incontri”. Roma

Carlin J (1990) Refugee and immigrant populations at special risk: women, children and the elderly. In: Holtzman W, Bornemann T (eds) Mental health of immigrants and refugees. Hogg Foundation for Mental Health, Austin, pp 224–233

Castellini F, Colombo M, Maffeis D, Montali L (2011) Sense of community and interethnic relations: comparing local communities varying in ethnic heterogeneity. J Community Psychol 39:663–667. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20459

Ceccagno A (1999) Interazioni con il tessuto socioeconomico e autoreferenzialità nelle comunità cinesi in Italia. Mondo Cinese 101:73–95

Chae M, Foley P (2010) Relationship of ethnic identity, acculturation, and psychological well-being among Chinese, Japanese, and Korean Americans. J Couns Dev 88:466–475. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00047.x

Cheng AW, Rizkallah S, Narizhnaya M (2020) Individualism vs. collectivism. In: Carducci BJ, Nave CS, Mio JS, Riggio RE (eds) The Wiley encyclopedia of personality and individual differences: clinical, applied, and cross-cultural research. Wiley, Hoboken, pp 287–297

Chung A (2013) From caregivers to caretaker: the impact of family roles on ethnicity among children of Korean and Chinese immigrant families. Qual Sociol 36(3):279–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-013-9252-x

Cologna D (2002) Bambini e famiglie cinesi a Milano. Materiali per la formazione degli insegnanti del materno infantile e della scuola dell’obbligo. Franco Angeli, Milano

Cologna D (2005) Differential Impact of transnational ties on the socio-economic development of origin communities: the case of chinese migrants from Zhejiang Province in Italy. Asian Pac Migr J 14:121–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/011719680501400107

Cologna D (2009) Giovani cinesi d’Italia: una scommessa che non dobbiamo perdere. In: Visconti LM, Napolitano EM (eds) Cross generation marketing. Milano, Egea, pp 259–282

Cologna D, Breveglieri L (2003) I figli dell’immigrazione, ricerca sull’integrazione dei giovani immigrati a Milano. Franco Angeli, Milano

Concepcion W, Kohatsu E, Yeh C (2013) Using racial identity and acculturation to analyze experiences of racism among Asian Americans. Asian Am J Psychol 4(2):136–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027985

Cortini M, Tria S (2014) Triangulating qualitative and quantitative approaches for the analysis of textual materials: an introduction to T-lab. Soc Sci Comput Rev 32(4):561–568. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439313510108

Crocetti E, Fermani A, Pojaghi B, Meeus W (2011) Identity formation in adolescents from Italian, mixed and migrant families. Child Youth Care Forum 40(1):7–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-010-9112-8

Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL, Kawakami K (2003) Intergroup contact: the past, present, and the future. Group Process Intergroup Relat 6(1):5–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430203006001009

Fang K, Friedlander M, Pieterse A (2016) Contributions of acculturation, enculturation, discrimination, and personality traits to social anxiety among Chinese immigrants: a context-specific assessment. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 22(1):58–68. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000030

Gonzalez R, Rupert B (2017) The influence of direct and extended contact on the development of acculturation preferences among majority members. In: Vezzali L, Stathi S (eds) Intergroup contact theory: recent developments and future directions. Routledge, New York, pp 31–52

Ghuman PAS (1991) Best or worst of two worlds? A study of asian adolescents. Educ Rev 33:121–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013188910330205

Hofstede G (2019) What about China? https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country/china/. Accessed 1 May 2019

Hofstede G, Minkov M (2010) Long- versus short-term orientation: new perspectives. Asia Pac Bus Rev 16(4):493–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602381003637609

Hofstede G, Hofstede GJ, Minkov M (2010) Cultures and organizations: software of the mind. Revised and expanded, 3rd edn. McGraw-Hill, New York

Human Rights Watch (2019) World Report 2019. Our annual review of human rights around the globe. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2019/country-chapters/european-union#1007e1/ Accessed 1 May 2019

Jodelet D (2003) Aperçussur les Methodologies Qualitatives. In: Moscovici S, Buschini F (eds) Les Méthodes des Sciences Humaines. PUF, Paris, pp 139–162

Kao G (1995) Asian Americans as model minorities? A look at their academic performance. Am J Educ 103(2):121–159. https://doi.org/10.1086/444094

Kao G (1999) Psychological well-being and educational achievement among immigrant youth. In: Hernandez D (ed) Children of immigrants: health, adjustment, and public assistance. National Academy Press, Washington, pp 410–477

Lancia F (2012). T-LAB pathways to thematic analysis. Accessed Jan https://www.tlab.it/en/tpathways.php

Latham K (2015) Media and discourses of chinese integration in Prato, Italy: some preliminary thoughts. In: Baldassar L, Johanson G, McAuliffe N, Bressan M (eds) Chinese migration to Europe. Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp 139–157

Latham K, Wu B (2013) Chinese immigration into the EU: new trends, dynamics and implications. ECRAN-Europe China Research and Advice Network

Lee S (1996) Unraveling the “Model Minority” Stereotype: listening to Asian American youth. Teacher College Press, New York

Lytle A (2018) Intergroup contact theory: recent developments and future directions. Soc Justice Res 31(4):374–385

Lockett M (1988) Culture and the problems of Chinese management. Organ Stud 9(4):475–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/017084068800900402

Mannarini T, Talò C, Mezzi M, Procentese F (2018) Multiple senses of community and acculturation strategies among migrants. J Community Psychol 46(1):7–22

Markova I, Linell P, Grossen M, Orvig AS (2007) Dialogue in focus groups. Exploring socially shared knowledge. Equinox, London

McGuire W, McGuire C (1981) The spontaneous self-concept as affected by personal distinctiveness. In: Lynch M, Ardyth N-H, Gergen K (eds) Self-concept: advances in theory and research. Ballinger, Cambridge, pp 147–171

Merton R (1972) Insiders and outsiders: a chapter in the sociology of knowledge. Am J Sociol 78(1):9–47

Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca (2015) Alunni con cittadinanza non italiana: la scuola multiculturale nei contesti locali. RapportoNazionale 2014/2015

Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali (2018) La comunità cinese in Italia. Rapporto annuale sulla presenza dei migranti (Chinese community in Italy. Presence of migrant annual report). https://www.lavoro.gov.it/documenti-e-norme/studi-e-statistiche/Documents/Rapporti%20annuali%20sulle%20comunit%C3%A0%20migranti%20in%20Italia%20-%20anno%202018/Cina-rapporto-2018.pdf/. Accessed 1 May 2019

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) (2011) Asian-American and Pacific Islander Mental Health. Report from a NAMI Listening Session. http://www.drjeiafrica.com/Dr._Jei_Africa/Media_files/NAMIAAPI.pdf/. Accessed 1 May 2019

Nielsen I, Paritski O, Smyth R (2012) A minority-status perspective on intergroup relations: a study of an ethnic Chinese population in a small Italian Town. Urban Stud 49(2):307–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098010397396

Ottati G, Cologna D (2015) The Chinese in Prato and the current outlook on the Chinese-Italian experience. In: Baldassar L, Johanson G, McAuliffe N, Bressan M (eds) Chinese migration to Europe. PalgraveMacmillan, London, pp 29–48

Passini S, Villano P (2018) Justice and immigration: the effect of moral exclusion. Int J Psychol Res 11(1):42–49. https://doi.org/10.21500/20112084.3262

Pedone V (2004) Contesti extrascolastici di socializzazione della seconda generazione cinese. Mondo Cinese 121:33–43

Pedone V (2008) Il vicino cinese. La comunità cinese a Roma. Nuove edizioni romane, Roma

Pedone V (2011) ‘As a rice plant in a wheat field’: identity negotiation among children of Chinese Immigrants. J Mod Ital Stud 16(4):492–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354571X.2011.593759

Pertiwi Y, Geers A, Lee Y-T (2020) Rethinking intergroup contact across cultures: predicting outgroup evaluations using different types of contact, group status, and perceived socio-political contexts. J Pac Rim Psychol 14(e16):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/prp.2020.9

Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR, Wagner U, Christ O (2011) Recent advances in intergroup contact theory. Int J Intercult Relat 35(3):271–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.03.001

Phinney J (1990) Ethnic identity in adolescence and adults: review of research. Psychol Bull 108:499–514. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499

Pieke F (1988) Introduction. In: Benton G, Houndmills FP (eds) The Chinese in Europe. Macmillan, Basinstoke, p 15

Pivetti M, Di Battista S, Pesole M, Di Lallo A, Ferrone B, Berti C (2018) Animal, human and robot attribution: ontologization of Roma, Romanian and Chinese groups in an Italian sample. Open Psychol J 11:65–76. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874350101811010065

Reicher S, Haslam A, Rath R (2008) Making a virtue of evil: a five-step social identity model of the development of collective hate. Soc Pers Psychol Compass 2(3):1313–1344. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00113.x

Robles-Llana P (2018) Cultural identities of children of Chinese migrants in Spain: a critical evaluation of the category 1.5 generation. Identity 18(2):124–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2018.1447481

Sai Lopez A (2015) Mujeres y Sociedad Civil en la Diaspora China. Inter Asia Papers 47:1–31

Sam D, Berry J (1995) Acculturative stress among young immigrants in Norway. Scand J Psychol 36:10–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.1995.tb00964.x

Sam D, Vedder P, Liebkind L, Neto F, Virta E (2008) Immigration, acculturation and the paradox of adaptation in Europe. Eur J Dev Psychol 5(2):138–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405620701563348

Statistiche tuttitalia IT, Cinesi in Italia (2021a) https://www.tuttitalia.it/statistiche/cittadini-stranieri/repubblica-popolare-cinese/. Accessed 1 Nov 2021

Statistiche tuttitalia IT, Cittadini stranieri San Benedetto del Tronto (2021b) https://www.tuttitalia.it/marche/provincia-di-ascoli-piceno/statistiche/cittadini-stranieri/repubblica-popolare-cinese/. Accessed 1 Nov 2021

Stein J-P, Lu X, Ohler P (2018) Mutual perceptions of Chinese and German students at a German university: stereotypes, media influence, and evidence for a negative contact hypothesis. Compare 6:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2018.1477579

Tajfel H (1979) Human intergroup conflict: useful and less useful forms of analysis. In: von Cranach M, Foppa K, Lepenies W, Ploog D (eds) Human ethology: claims and limits of a new discipline. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 396–422

Tajfel H (1981) Human groups and social categories. Studies in social psychology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Triandis H (2001) Individualism-collectivism and personality. J Pers 69:907–924. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.696169

Various Authors (2015) Codice etico (Code of Ethics of the Italian Psychology Association). Accessed http://www.aipass.org/node/11560

Verrocchio MC, Cortini M, Marchetti D (2012) Assessing child sexual abuse allegations: an exploratory study on psychological reports. Int J Multiple Res Approach 6(2):175–186. https://doi.org/10.5172/mra.2012.6.2.175

Xing L (2001) Bicultural identity development and Chinese community formation: an ethnographic study of chinese schools in Chicago. Howard J Commun 12(4):203–220

Yang H, Liao Q, Huang X (2008) Minorities remember more: the effect of social identity salience on group-referent memory. Memory 16:910–917. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210802360629

Yeh C, Kim A, Pituc S, Atkins M (2008) Poverty, loss, and resilience: the story of Chinese immigrant youth. J Couns Psychol 55(1):34–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.55.1.34

Tropp LR, Pettigrew TF (2005) Relationships Between Intergroup Contact and Prejudice Among Minority and Majority Status Groups. Psychological Science 16(12) 951–957 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01643.x

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi G. D'Annunzio Chieti Pescara within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, CB, SPa and FDF.; methodology, CB, FDF and SPo; software, SPo; validation, CB, FDF and SPo; formal analysis, CB, FDF and SPo; investigation, FDF; resources, CB and FDF, data curation, FDF and SPo; writing—original draft preparation, CB and FDF; writing—review and editing, CB, SPa and FDF; visualization, FDF, supervision, CB; all authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

In Italy, research was compliant with the Code of Ethics of the Italian Psychology Association (Various Authors, 2015), which is inspired to the Declaration of Helsinki. As no Institutional Review Board for Psychology research was available at the institution with which the social psychology researchers involved in this study are affiliated (i.e., the University of Chieti-Pescara), no request for approval could be submitted.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Berti, C., Potì, S., Passini, S. et al. The grasshopper and the ant: Chinese teenagers and their representation of Italian people. SN Soc Sci 2, 181 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-022-00475-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-022-00475-9