Abstract

Background

Prompted by the Covid-19 pandemic and the need to ensure timely and safe access to medicines during a pandemic, the aim of this study was to compare and contrast the EU and US regulations, processes, and outcomes pertaining to the granting of accelerated Marketing Authorizations (MAs) for COVID-19 vaccines and treatments with a view to determining how effective these regulations were in delivering safe medicines in a timely manner.

Methods

MAs for medicines approved for Covid-related indications in the first two pandemic years (March 2020–February 2022) were identified using the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) websites. Authorization reports and utilized regulations were reviewed to determine and compare approval timelines, facilitated pathways, accepted clinical evidence, and effectiveness of the regulations by assessing them against time and safety standards.

Results

By the end of February 2022, the EMA and FDA had granted 12 and 14 MAs, respectively. Two EU and two US approvals were issued in relation to new indications for already-approved treatments; the remaining ones were first-time approvals of novel vaccines and treatments. The median time to approval was 24 days for the EMA’s conditional MAs and 36 days for the USFDA’s Emergency Use Authorizations (EUA) for all Covid-19 medicines. This is compared with 23 and 28 days, respectively, specifically for first-time novel vaccines and treatments authorized by both USFDA and EMA. The USFDA and EMA differed markedly in terms of the time taken to approve new indications of already-approved treatment; the USFDA took 65 days for such approval, compared with 133 days for the EMA. Where MAs were issued by both authorities, USFDA approvals were issued before EMA approvals; applications for approval were submitted to the FDA before submission to the EMA. Three EU and two US MAs were based on data from two or more phase 3 clinical trials; the remaining ones were based on single trial data. Only six EU and four US trials had been completed by the time of authorization. This was in line with regulations. While the applicable regulations shared many similarities, there were marked differences. For instance, the EU’s conditional MA regulation pertains only to first approvals of new treatments. It does not cover new indications of already-approved treatments. This contrasts with the US, where the EUA regulation applies to both types of applications, something that may have impacted approval timelines.

Overall, both EU and US utilized regulations were considered to be effective. For most cases, utilizing such regulations for Covid-19 MAs resulted in faster approval timelines compared to standard MAs. They were flexible enough to manage the process of granting emergency approvals while maintaining strict requirements and allowing comprehensive reviews of the supporting evidence.

Conclusion

US and EU regulations were effective in ensuring timely accelerated market access to Covid-19 medicines during the pandemic without compromising the approval standards related to safety or efficacy. The population in both regions will receive comparable access to medicines during a pandemic if sponsors submit their applications to both authorities in parallel.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared Covid-19 a global pandemic in March 2020 [1]. Consequently, many pharmaceutical companies and sponsors initiated clinical trial programs to find safe and effective vaccines and/or treatments. These trials were either to support authorization of new molecular entities or for approval of additional therapeutic indications of already-authorized medicines. By 2021, some vaccines and treatments had received emergency use or conditional marketing authorization (MA) both in the European Union (EU) and United States of America (USA) on an accelerated basis [2,3,4].

Market access of new medicines is highly regulated in most developed countries worldwide. The regulatory authorities are responsible for reviewing the safety, efficacy and quality evidence provided by pharmaceutical companies in order to grant marketing authorizations (MAs) for new medicines or for new therapeutic indications of already-authorized medicines. The US Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) are the regulatory authorities in the USA and EU, respectively, and considered the biggest regulatory authorities worldwide.

Both authorities have their own authorization procedures, requirements, and MA application review timelines. For standard new innovative drugs, the timelines from development to final approval can be lengthy and reach 10–20 years [5]. However, both authorities have facilitated pathways and tools to accelerate the development and approval timelines for medicines which fulfill certain criteria, such as if the medicine is for life-threatening disease where there are no alternatives, if it provides substantial improvement over existing treatments, or if it is for public health threats [6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. There are different types of facilitated pathways in the USA and EU that have been introduced gradually over the past decades, each with set eligibility criteria and conditions. There were reports that the EMA was more restrictive than USFDA in granting facilitated designations for drugs not having high therapeutic value between 2007 and 2017; i.e., many drugs, which were rated as having low therapeutic value, received expedited approvals by USFDA but not by EMA [13, 14].

In addition, although sponsors may submit the same clinical evidence for the same indications and other details about the use of a medicine, the regulatory authorities may not approve them as they are and request some changes. For instance, differences have been found between the indications of new medicines in USA and EU [15, 16], as well as routes of administration, dosage forms, strengths, and posology of priority review products approved by USFDA and EMA. Between 1999 and 2011, the EMA approved more indications than USFDA for the same drugs, yet EMA-approved indications were more restrictive, i.e., the drug indication or use was limited to factors such as the disease state, previous therapy failure, or inappropriate alternative therapies [15].

The Covid-19 pandemic presented an unprecedented global threat, which made fast approvals of effective and safe treatments paramount. Indeed, regulatory authorities globally granted emergency or conditional approvals to Covid-19 vaccines and treatments, including by the USFDA and EMA. However, approvals via facilitated pathways differ between the USFDA and EMA, and it was not known if the population of both regions had comparable access to officially authorized lifesaving medicines. Secondly, the speed of approvals led to concerns over potentially compromising the safety and efficacy standards of Covid-19 medicines [17,18,19]. Such concerns had previously been noted in relation to pre-Covid-19 use of facilitated approval pathways, including drug safety concerns, insufficient or delayed studies to confirm preliminary evidence, potential regulatory capture associated with the fees paid for expedited review, and public misperception of the therapeutic value of drugs approved via expedited pathways [20].

Background on Marketing Authorizations of New Medicines

This section provides an overview of regulatory pathways for medicines MAs, in order to describe and compare the different application pathways in USA and EU.

Regulatory Pathways Overview in USA

After completing clinical trials, and in line with the standard new drug application approval pathway described in Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act 505(b), a New Drug Application (NDA) is submitted containing full safety and efficacy reports to USFDA’s Center for Drugs Evaluation and Research (CDER) for all new innovative drugs to be approved for market entry [21]. Section 505(j) of the same Act specifies that the approval of all generic drug products is via an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway, with evidence that the generic drug is equally safe and effective as the approved drug.

Once the application is filed, the Code of Federal Regulations stipulates that the FDA review should be completed within the specified timeframe of 180 days, which is subject to extension if required [22]. Following this, the FDA issues either an approval letter to market if there are no refusing reasons, or a response letter detailing deficiencies and recommendations to make the application viable [22].

The licensing of biological products is regulated under separate regulation section. As per the Public Health Service Act, a Biological License Application (BLA) is submitted to the USFDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) or (CDER) instead of NDA. The BLA should contain data derived from non-clinical laboratory and clinical studies which demonstrate that the manufactured product meets prescribed requirements of safety, purity, and potency. USFDA similarly issues complete response letter detailing deficiencies and recommendations if any [23].

In practice, NDAs and BLAs have 10-month standard review timeline or 6-month priority review timeline; both following a 60-day filing period. This is to meet the performance goals for the review timelines set by the Prescription Drug Used Fee Act (PDUFA), which was first created by Congress in 1992 to authorize the FDA to collect fees from companies to expedite the drug approval process [113].

The USFDA has the following regulatory pathways to expedite the development and application review timelines of both drugs and biologics in cases of unmet medical need or for serious life-threatening conditions, [6]:

-

Fast track designation

-

Breakthrough therapy designation

-

Accelerated approval

-

Priority review

Table 1 summarizes the details extracted from the USFDA’s guidance for expedited programs [6].

These facilitated pathways have been successfully used since 1987 [20, 24,25,26,27]. Nearly half of the approvals via facilitated pathways were for first in class medicines [20, 24], and the most common disease class was oncology treatments [25]. “Priority review” has been used the most, and “accelerated approval” the least [24, 25], with the combination of facilitated pathways having been shown to be more efficient in shortening the development and review times compared to “priority review” alone [26]. In addition to these expedited programs, the Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) legal tool allows the USFDA to protect the public against chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear threats including infectious diseases by facilitating the availability and use of medical countermeasures needed during public health emergencies [7, 28]. Medical countermeasures include biologics such as vaccines, drugs, and medical devices [29]. In 2009, USFDA issued EUAs during the influenza H1N1 pandemic for many antiviral drugs such as Oseltamivir. In 2011, they issued EUAs for doxycycline for inhalational anthrax post-exposure prophylaxis. EUA was used successfully during anthrax and influenza H1N1 pandemics and they were considered first major tests for this legal tool [27].

Regulatory Pathways Overview in European Union

In the European Union, Directive 2001/83/EC [30] allows several procedures for marketing authorization of new medicines:

-

Centralized Procedure: “Marketing Authorization Application” is submitted to EMA, and following approval, the European Commission issues final authorization, valid for all EU member states.

-

Decentralized Procedure: The same MA application is submitted simultaneously to several EU member states. The determined Reference Member State leads the assessment. Upon approval, all member states issue national authorizations.

-

Mutual Recognition Procedure: If a medicine has a national authorization in one EU member state, the MA application can be submitted in other member states, which relies on the original evaluation.

-

National Procedure: The MA application is submitted through the national procedure in one EU member state, if the medicine is intended only for that member state.

All medicinal products, whether biological or chemical, will go through the same type of MA application.

EMA MA follows the centralized procedure (EC 726/2004), which is the compulsory route for many new innovative medicines indicated for treatment of certain diseases such as cancer, diabetes, viral diseases, and acquired immune deficiency syndrome. It is also compulsory for orphan and advanced therapy medicinal products, and for medicinal products developed by certain biotechnological processes such as by recombinant DNA technology or hybridoma, and monoclonal antibody methods [31]. The EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use must give its opinion within 210 days of receipt of a valid application.

The following facilitated pathways are available under the EU centralized procedure:

-

Conditional MA: Under EC No 507/2006 [32], a conditional MA can be granted without comprehensive safety and efficacy clinical data, but only if the medicinal product is for public health benefit which outweighs risks, if unmet medical need is fulfilled, and if the applicant can provide comprehensive data in future. This is applicable for medicinal products for seriously debilitating or life-threatening diseases; or for medicinal products needed in emergency situations, or for orphan designated medicinal products for rare diseases, or in response to public health threats duly recognized either by the WHO or by the Community in the framework of Decision No 2119/98/EC. The EMA has additional detailed guidelines for granting conditional MAs [8].

-

MA under Exceptional Circumstances: Under Article 14(8) of Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 [31], the EMA can grant authorization under specific procedures in exceptional circumstances for objective verifiable reasons, specifically when the applicant can justify that comprehensive data cannot be provided. This authorization can only be continued with annual assessment of the conditions. The EMA has guidance for these specific procedures [9].

-

Accelerated Assessment: Article 14 (9) of Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 [31] states that the applicant can request accelerated assessment for a MA application if the medicinal product has public health interest and if it demonstrates therapeutic innovation. If the request is accepted, the application review timeline can be reduced from 210 to 150 days. Further EMA guidance on this procedure exists [10].

-

Priority Medicines (PRIME) Scheme: This was launched by EMA in 2016, also based on the accelerated assessment permitted under Article 14 (9) of Regulation (EC) No 726/2004. This scheme aims to support the development of a medicinal product if it is for unmet medical need or if it has advantage over other existing therapies, by enhancing the interaction and early dialogue with the developers and providing scientific advice [11, 12].

Table 2 summarizes the details of EMA facilitated pathways for new MAs.

Interestingly, between 1995 and 2016, the conditional MA pathway did not accelerate the approval process for innovative drugs; in fact, review timelines were longer than standard review timelines due to longer administrative periods between EMA’s final decision and the official European Commission decision [33, 34]. Furthermore, longitudinal analysis conducted on the implementation of the conditional MA instrument emphasized that the majority did not use the conditional MA pathway in a prospectively planned fashion but instead this option appeared to be used when submitted data were not strong enough to justify the standard approval [34]. Use of the exceptional circumstances pathway also did not accelerate the approval process between 2006 and 2009, due to longer clock-stop periods for the sponsor to respond to EMA’s queries [33].

Similarities and Differences in Regulatory Pathways between USA and EU

In both regions, the related regulatory authorities (USFDA and EMA) require that an application is submitted for medicinal products for review and approval before market entry. In USA, there is one submission procedure with different types of applications, i.e., NDA for drugs or BLA for biologicals. In the EU, there is one type of MA application for drugs and biologicals, but under four different procedures, i.e., centralized, decentralized, mutual recognition, and national procedures.

USFDA and EMA have standard timelines to review applications. In both regions, facilitated pathways exist to accelerate development and/or the review timelines for exceptional cases such as medicinal product for life-threatening disease or without alternatives. However, the pathways, terminologies, and their conditions differ between the two regions. Some are equivalent pathways with different terminologies, such as the US breakthrough therapy designation and the EU priority medicines (PRIME) scheme. Other examples are the US fast track designation or priority review and the equivalent EU accelerated assessment, and the US emergency use authorization and EU conditional MA for emergency authorizations during recognized public health threats.

Some pathways are specific to each region with no equivalent pathway in the other region, such as the EU MA under exceptional circumstances, which approves without comprehensive clinical confirmatory studies under specific conditions.

Table 3 summarizes the previously mentioned applications and pathways available in USFDA and EMA centralized procedures to demonstrate the equivalency in both regions.

Study Aim and Objectives

The aim of this study was to compare and contrast the EU and US regulations, processes, and outcomes pertaining to the granting accelerated MAs for Covid-19 vaccines and treatments with a view to determine how effective these regulations were in delivering safe medicines in a timely manner.

The study's objectives were as follows:

-

i.

To identify and compare all official marketing authorizations granted by EMA and USFDA for Covid-19 vaccines and treatments, and

-

ii.

To identify and compare the corresponding implemented regulations and their effectiveness.

Methodology

Identification and Comparison of MAs for Covid-19 Vaccines and Treatments in EU and USA

In order to address the first objective, the official EMA and USFDA websites [2,3,4] were searched to find all Covid-19 vaccines and treatments that were officially approved during the Covid-19 pandemic on an accelerated basis. In the EU, all Covid-19 MAs had been granted through the EMA centralized procedure. The inclusion and exclusion criteria listed in Table 4 were used to extract relevant data published by 28 February 2022, giving a 2-year timeframe since the first WHO declaration of a pandemic.

The European Public Assessment Reports (EPARs)Footnote 1 for initial authorizations and US authorization letters with accompanying review memorandumFootnote 2 documents were accessed for each identified Covid-19 vaccine and treatment MA “Covid-19 MA.”

The following data were extracted into excel from EPARs and US review memorandum documents: product category (vaccine or treatment), entity status (new entity or new indication of previously authorized entity), therapeutic group of entity (ATC code if available), approved indication(s), application submission date, initial authorization date, authorization pathway (standard or any facilitated pathway), number and design of accepted pivotal clinical trials for safety and efficacy evaluation, and issued post-authorization obligations.

For the Covid-19 MAs approved by facilitated pathways, the conversion status to standard authorization was also recorded. Additional searches were conducted in “Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drug” and “Licensed Biological Products” databases [35, 36] to determine if any US Covid-19 MAs were based on standard NDAs or BLAs. If so, standard respective submission and approval dates were extracted from the corresponding “Summary Basis of Regulatory Action” or “Summary Review” documents.

Based on the extracted details, Covid-19 MAs were compared for the following points:

-

Number and type of Covid-19 Medicines authorized by EMA and USFDA,

-

Common Covid-19 medicines which were authorized by both EMA and USFDA,

-

Approval timelines of Covid-19 MAs, calculated as the period between official application submission and initial authorization dates,

-

Used authorization pathways (standard or facilitated pathways),

-

Status of conversion to standard authorization,

-

Variety of therapeutic groups,

-

Approved indications,

-

Accepted pivotal clinical trials and type of issued post-authorization clinical requirements.

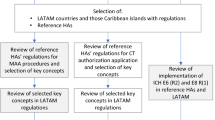

Identification and Comparison of the Utilized EU and US Regulations for Covid-19 MAs

In order to address objective 2, the following searches were undertaken:

-

1.

European Union’s (EudralexFootnote 3—Volume 1—Pharmaceutical legislation for medicinal products for human use) official website [38], which publishes the rules and regulations governing medicinal products in the EU. (The volume containing guidelines is not considered since guidelines are not legally binding documents).

-

2.

Title 21 of US Code of Federal Regulations [39] and Titles 21 and 42 of US Code [40], which govern food, drugs, and biologics in the United States.Footnote 4

Using the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed in Table 5, the relevant regulations were accessed via official websites and then screened and reviewed to extract the regulations related to the following:

-

i.

Procedures, approval timelines, clinical requirements, and post-authorization requirements for marketing authorization of new vaccines and treatments intended for viral diseases.

-

ii.

Procedures and approval timelines for the approval of new therapeutic indications of already-approved entities.

-

iii.

Criteria, procedures, and approval timelines for the used facilitated pathways or designations for Covid-19 MAs.

The utilized regulations and processes used for approval of Covid-19 vaccines and treatments during the pandemic were compared between USFDA and EMA.

The effectiveness of the utilized regulations in delivering safe medicines in a timely manner during an emergency situation was assessed by observing them against the following time and safety standards:

-

1.

If utilizing such regulations for Covid-19 MAs resulted in faster approval timelines compared to standard MAs.

-

2.

If the utilized regulations were flexible enough to manage the process of granting emergency approvals while maintaining strict requirements.

-

3.

If the clinical trials supporting the Covid-19 MAs were in line with the regulations and requirements.

-

4.

If the regulatory authorities were able to make a comprehensive assessment of all data supporting the Covid-19 MAs despite fast approval timelines.

Results

Identification and Comparison of MAs for Covid-19 Vaccines and Treatments in EU and USA

Number and Type of MAs for Covid-19 Vaccines and Treatments

-

By 28 February 2022, the EMA and USFDA had granted a total of 12 and 14 MAs for Covid-19 vaccines and treatments, respectively.

-

The EMA authorized five vaccines and seven treatments, and the USFDA authorized three vaccines and eleven treatments.

-

All vaccines were new entities. Two of the seven EMA Covid-19 treatments and two of the 11 USFDA Covid-19 treatments were previously authorized entities for which a new Covid-19 treatment indication was granted; the rest were new entities.

-

Eight of all available Covid-19-related products were approved by both USFDA and EMA (three vaccines and five treatments), four products were approved only by EMA (two vaccines and two treatments), and six products were approved only by US (six treatments).

Table 6 lists the EMA and USFDA authorized Covid-19 vaccines and treatments, alongside the accessed references of initial authorization EPARs and US emergency authorization letters with accompanying review memorandums. Figure 1 illustrates the comparison between EMA and USFDA in number and type of Covid-19 MAs.

Approval Timelines, Facilitated Pathways, and Conversion Status to Standard Approval

-

All USFDA initial approvals were under the Emergency Use Authorization pathway with some having additional Fast Track Designation.

-

Seven EMA approvals were under the Conditional MA pathway, and five were under Standard MAs. All EMA new entity approvals had gone through a rolling review procedure following Covid-19 EMA pandemic Task Force (COVID-ETF) recommendation.

-

None of EMA conditional approvals had been converted to standard approval by 28 February 2022; in USA, three of all emergency approvals had been converted to standard approval.

Approval Timeline Comparison (EMA Conditional MA vs. USFDA Emergency Use Authorization):

The median approval timeline was 24 days for all Covid-19 products authorized under the EMA’s Conditional MA pathway, whereas the median approval timeline for the USFDA’s Emergency Use Authorization pathway was 36 days.

Approval Timeline Comparison (For Covid-19 MAs authorized by both EMA and USFDA):

-

○ The USFDA approved all new novel entities faster (median 23 days) than the EMA (median 28 days).

-

○ The USFDA approved new entity vaccines faster (median 21 days) than the EMA (median 24 days), yet the EMA approved new entity treatments faster (median 29 days) than the USFDA (median 40 days).

-

○ A marked difference was also found between the approval timelines for new indication addition to already-authorized entities, with USFDA authorization faster (median 65 days) than EMA (median 133 days).

-

○ The USFDA approved all Covid-19 vaccines and treatments before the EU. Sponsors submitted applications first to USFDA before submitting to the EMA for seven out of eight cases.

Figure 2 and Tables 7 and 8 illustrate the details of approval timelines and pathways.

Therapeutic Groups, Approved Indications, and Accepted Pivotal Clinical Trials

-

The Covid-19 vaccines and treatments authorized in EU and USA varied between different pharmacotherapeutic groups as shown in Fig. 3.

-

EMA and USFDA authorized vaccines had the same approved indications, but indications of most of treatments differed. For example, Casirivimab co-packaged with Imdevimab was authorized for treatment and prevention in the EU but only for treatment in the USA. Other examples include Nirmatrelvir co-packaged with ritonavir, and Tocilizumab, which the EMA authorized only for use in adults, but the USFDA authorized them for use in adults and children. Table 9 lists the statements of all approved indications.

-

All clinical trials supporting US and EU applications for MA of Covid-19 indications were randomized and placebo controlled.

-

Two or more pivotal phase 3 clinical trials underpinned only three of twelve EMA authorizations and two of fourteen USFDA authorizations for Covid-19 indications (a minimum of two is recommended [42]). The remaining approvals were based on only one single pivotal phase 3 clinical trial. Two USFDA authorizations were approved without a pivotal phase 3 clinical trial, with one of them authorized based on totality of scientific evidence and small multiple trials, and the other on one phase 1/2 trial.

-

Only six of 12 clinical trials supporting EMA applications and four of 14 clinical trials supporting USFDA applications for Covid-19 indications had been completed, with the remainder still “ongoing” at the time of authorization.

-

The EMA issued post-authorization clinical obligations for Covid-19 indications which received conditional authorization, with most being obligations to continue the ongoing clinical trials. The USFDA granted emergency use authorizations based on the sponsor’s plans to continue the ongoing trials for some applications and by identifying outstanding issues/data gaps to provide additional confirmatory studies or requirements for some other applications.

Figure 4 illustrates these findings and Table 9 lists all the therapeutic groups, approved indications, accepted pivotal clinical trials, and post-authorization obligations for EU and US Covid-19 MAs.

Identification and Comparison of the Utilized EU and US Regulations for Covid-19 MAs

Following the processes outlined in Sect. "Identification and Comparison of the Utilized EU and US Regulations for Covid-19 MAs", the identified EU and US regulations utilized in MAs of Covid-19 vaccines and treatments are listed in Tables 10 and 11, respectively. Key points of these regulations are summarized in Tables 12 and 13, respectively.

By analyzing the key points of both EU and US regulations utilized in marketing authorization of Covid-19 vaccines and treatments, the following similarities and differences, and effectiveness of regulations were observed:

Similarities:

-

Both EU and US regulations have provisions for MA of medicinal products that can be used during recognized public health threats like pandemics to achieve accelerated authorization. These are EU Conditional MA and US Emergency Use Authorization regulations.

-

There are no stipulated approval timelines for either EU Conditional MA or US EUA. They can be granted as soon as the criteria and minimum requirements are fulfilled.

-

The requirements related to clinical studies are similar. Both regulations specify the main characteristic of clinical studies to be adequate and well controlled without mentioning the number of required pivotal clinical studies.

-

Rolling review features, in which the sponsor can submit data in many rolling review cycles as they become available before the formal application submission, are not mentioned in either EU or US regulations. Both regulatory authorities introduced this tool through guidelines, which are not legally binding.

Differences:

-

In USA, drugs and biologics are regulated separately and there are different application types (NDA and BLA) for MA. In the EU, drugs and biologics are regulated under the same regulations with the same MA application.

-

The EU conditional MA follows the same procedure as the standard MA, whereas the US EUA is a different procedure than the standard NDA or BLA.

-

The EU has one centralized application, which results in either standard or conditional MA depending on the completeness of the submitted evidence. In USA, there is EUA application at the beginning and separate NDA/BLA at a later stage if the sponsor intends to obtain standard approval.

-

The EU conditional MA has more strictly regulated post-authorization obligations, whereas US EUA is granted based on a sponsor’s plans for clinical trials continuation and mentions only identified gaps.

-

The EU conditional MA regulation is applicable only to authorization of new entities but not for addition of new therapeutic indications for already-authorized entities. The US EUA regulation is applicable for both new entities and new indications of existing entities.

-

The EU variation regulation allows authorization with missing pharmaceutical, clinical, or non-clinical data subject to post-authorization obligation in emergency cases such as a pandemic. US variations regulation does not mention anything about the acceptability of missing data.

-

The EMA regulation stipulates that a conditional MA is renewed annually, whereas a US EUA stays valid until termination, or it is revoked by declaration by secretary if the circumstances for issuance of such authorization no longer exist.

-

Unlike EU, the “rolling review” feature, in which the sponsor can submit data in many rolling review cycles as they become available before the formal application submission, is not a standalone tool in the US but is instead considered one of the features related to “Fast Track Designation” as per FDA guidance. The “Fast Track Designation” itself is regulated by US Code.

Effectiveness of the Utilized Regulations:

By assessing the utilized regulations against the time and safety standards listed under Sect. "Identification and Comparison of the Utilized EU and US Regulations for Covid-19 MAs", the following is observed:

-

1.

For most cases, Covid-19 MAs had faster approval timelines compared to the standard MAs. EU and US timelines and procedures implemented for COVID-19 case, and EU and US timelines and procedures used for other standard case approvals are illustrated in Figs. 5 and 6, respectively.

-

2.

The EU conditional and US EUA regulations were flexible. Additional facilitated pathways were implemented to further reduce the review timelines. At the same time, they both mandated strict criteria and conditions to be met as listed in Tables 12 and 13, respectively. Also, they enabled regulatory authorities to issue obligations to instruct continuation of the studies for more comprehensive data.

-

3.

The clinical trials with safety evidence, which supported the Covid-19 MAs, were all in line with the current regulations and requirements.

-

4.

Despite the fast approval timelines, the regulatory authorities were able to perform comprehensive reviews of the supporting evidence well in advance of the application submission through the rolling review feature.

There was an observation for visibility of such details in US initial EUAs. This is converted to a point for enhancement as recommendation to regulators under section "Recommendations to Regulators".

Discussion

Prompted by the Covid-19 pandemic, this study aimed to compare and contrast EU and US regulations, processes, and outcomes of granting accelerated marketing authorizations for Covid-19 vaccines and treatments, in order to determine how effective these regulations were in delivering safe medicines in a timely fashion during an emergency situation. All accelerated MAs for Covid-19 vaccines and treatments, and the associated utilized regulations, were identified and compared between the EU and USA, which enabled the identification of both efficiencies and limitations in regulations. Accordingly, recommendations are made for future enhancement.

Historic and Current Uses of Facilitated Pathways

Regulations for accelerated review of MA applications for new medicines have been developed in the EU and USA over the past two decades, so as to accelerate access to medicines treating serious conditions or unmet need. Many facilitated pathways exist in the US, which benefited the majority of new molecular entities in USA [24, 25, 27]. Facilitated pathways have also been used in the EU, but long administrative periods between EMA’s decision and final European Commission’s approval limited accelerated access [33, 34]. However, these historic delays in the EU were not observed during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Many studies investigating regulatory authority application review approval timelines for new innovative medicines reported that USFDA had faster review timelines and that new drugs were first approved in USA [15, 16, 43, 44]. This study showed that this continued during Covid-19. However, this was not because of faster approval USFDA timelines but because sponsors first submitted MA applications in USA and later in the EU.

Granting fast approvals for new medicines for serious conditions or unmet medical needs is, of course, not a new concept applied during the Covid-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, the Covid-19 pandemic emphasized the importance of good communication strategies which address public concerns and hesitancies which emerged in relation to the speed of Covid-19 vaccines and treatments regulatory approvals [17,18,19].

EU and US Regulations Utilized for Covid-19 MAs

The EU conditional MA and US emergency use authorization procedures had been introduced to facilitate accelerated MA of safe and effective new medicines during public health threats such as duly recognized pandemics. While the relevant regulations did not specify any review timelines, they were accompanied with other facilitated tools to further accelerate the development and review timelines.

This study has shown that the US and EU regulations both specify the main characteristics of clinical trials evidence for safety and efficacy, and that these need to be adequate and well controlled. The regulations in the EU and USA do not, however, mention how many pivotal clinical studies are required [45], and the standard perceived minimum of two pivotal clinical trials requirement in USA is based on a USFDA guidance document [42], without legally enforceable responsibilities. Hence, Covid-19 MAs based on one pivotal clinical trial was in line with current requirements.

Downing et al. [46] found that the clinical trials supporting both standard and facilitated US approvals for all novel drugs between 2005 and 2012 were randomized, double-blinded, and used either an active or placebo comparator. These authors also found that the median number of pivotal trials per indication was two both for standard and facilitated approvals, although 36.8% were approved based on a single pivotal trial.

Morant and Vestergaard [47] investigated whether there were differences in the reported number of EU pivotal clinical trials for standard and facilitated approvals. They found that between 2012 and 2016, indications approved via standard procedure were mostly based on clinical evidence from two or more pivotal clinical trials (61%), while the majority of the indications with a conditional MA (85%) and indications with a MA under exceptional circumstances (80%) were based on a single pivotal clinical trial.

Leyens et al. [48] found that between 2007 and 2015, there were differences in the accepted clinical trials characteristics supporting the facilitated approvals of new medicines between USFDA and EMA. For example, all EMA approvals were based at least on clinical phase II data, whereas the USFDA granted two approvals (out of 25) based on only phase I data. Indeed, most USFDA approvals were based on one or two clinical trials, whereas EMA approvals were based on at least two. However, the USFDA more often requested new confirmatory randomized controlled clinical trials, whereas EMA's common request was the completion of ongoing trials.

The current study revealed that both EU and US regulations were sufficiently effective to ensure fast authorization of Covid-19 vaccines and treatments during the pandemic.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the EU conditional MA accompanied by a rolling review procedure proved its worth for new entities. New indication approval of already-authorized entities did not, however, benefit from EU conditional MA and rolling review, so did not have accelerated authorization. In USA, the regulations of emergency use authorization were applicable to both new entities and new indications and hence both had faster approvals.

By studying the relevant regulations, the present study found that both US and EU regulations do not have provisions for rolling review, but that both authorities introduced this tool through non-legally binding guidelines. In the EU, the rolling review procedure was used as a standalone procedure under the EMA’s initiatives for acceleration of development support and evaluation procedures for Covid-19 treatments and vaccines [49]. In USA, rolling review is one of the features related to fast track designation.

This study showed that EU and US procedures were effective in ensuring that medicines approved with accelerated authorization were safe and effective. The rolling review ensured that dossier content and all data were reviewed well in advance of the official application submission and both conditional MA and emergency use authorization regulations specify criteria and conditions for authorization.

Importance of EMA and USFDA Approvals for Covid-19 Medicines

The WHO declared Covid-19 a global pandemic in March 2020 [1], and the USFDA and EMA initiatives to accelerate the development of promising vaccines and treatments and grant fast approvals thus had high importance during this time. Two years in, in March 2022, there were over 500 million confirmed Covid-19 cases worldwide, and the pandemic had claimed around 6 million lives [50].

The off-label use of medicines, whereby medicines are used for unapproved indications, increased during the Covid-19 pandemic [51]. Hence, it was crucial for regulatory authorities to grant speedy, official authorization to Covid-19 medicines to ensure safe and effective treatments. The USFDA was the fastest to grant an initial official emergency use authorization in May 2020 for Remdesivir, for the treatment of hospitalized patients with severe Covid-19 conditions. The authorization of Covid-19 convalescent plasma followed in August 2020, with all other US and EU approvals being granted gradually from November 2020.

Study Limitations and Strengths

One limitation of the current study is that it examined the Covid-19 MAs granted by two regulatory authorities only. However, the USFDA and EMA are two of the largest regulatory authorities, and the importance of their approvals is not limited to the USA and EU. They have big worldwide impact since many regulatory authorities rely on USFDA and/or EMA approvals to authorize medicines in their regions [52,53,54]. Accelerated and emergency approvals by USFDA and EMA had a major impact on saving millions of lives and on slowing down the progression of the pandemic, which had global economic effects [55].

Because the USFDA only publishes the full review history with the final NDA/BLA standard approval and not with emergency use initial authorization letter, the current study was unable to confirm if there were additional facilitated pathways beside the emergency use authorization for US Covid-19 vaccines and treatments, which were not converted to standard approval. The study did not search in press releases to avoid bias as some sponsors might not publish these details. Instead, the publication of the review history of facilitated pathways together with the emergency use initial review memorandums is picked up as one recommendation to regulators.

Another limitation is that the study did not address any revoked or terminated MAs in the study period. However, this is not due to limitation in information sources but because including revoked MAs will not provide efficient comparison in the outcomes and will not add value in addressing the aim of the study.

The current study also has many strengths. It investigated the facilitated pathways for marketing authorizations of new medicines introduced by two of the largest regulatory authorities worldwide. It provides an overview of the use of facilitated pathways historically and investigated their special use for Covid-19 vaccines and treatments. It is the first study, which compared the US emergency use authorization and EU conditional MA pathways, which are the only legal tools available for use during recognized pandemics. Moreover, this study investigated both new medicines and the addition of new therapeutic indication to already-authorized medicines. Furthermore, besides investigating Covid-19 MAs, this study also explored the underpinning regulations, which allowed a comparison of procedures used for standard vs. Covid-19 cases.

Recommendations to Regulators

Based on this study, the below points are recommendations for regulators in order to enhance regulation efficiency, especially during an emergency situation.

-

1.

Addition of provisions related to conditional variation approval for therapeutic indication addition to the European Committee Regulation (EC) No 507/2006 related to conditional marketing authorization.

-

2.

Addition of review history related to additional expedited pathways into the US published review memorandum of the initial emergency use authorization. This will ensure transparency of evidence reviewed by USFDA under expedited pathway like fast track designation and by rolling review prior to official application submission.

-

3.

Addition of provisions related to rolling review procedure to both the EU and US regulations, so that the sponsor can submit data as they become available in many rolling review cycles and before the formal application submission. These provisions can then standardize the rolling review process, conditions, criteria, and timelines.

Conclusion

Despite some variability and minor limitations found in regulations, this research demonstrated the overall efficiency of both US and EU regulations and practice in ensuring accelerated market access to safe and effective Covid-19 medicines during the pandemic. It opposed the perceived historic view that the USFDA is always faster than EMA in ensuring market access to new innovative medicines. In fact, the first US Covid-19 approvals were not related to faster approval timelines or more efficient practice, because the majority of sponsors submitted applications first in USA and later in EU. Provided sponsors submit in parallel in both regions, the populations in the USA and EU will receive parallel access to life saving medicines during any pandemic situation.

This study has further shown that fast approvals and accepted clinical trials were in alignment with current regulations and were not compromising approval standards related to safety or efficacy. Hence, communication strategies are suggested to also address public concerns and hesitancies toward Covid-19 vaccines and treatments with fast regulatory approvals.

Availability of Data and Material

The analyzed data supporting the results reported in this article can be found through hyperlinks to publicly archived datasets.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Notes

According to the Article 13(3) of Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 [31], EPAR is published for every human or veterinary medicine application that has been granted or refused a marketing authorization following assessment by Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use or Committee for Medicinal Products for Veterinary Use of EMA in the framework of the Central authorization of medicines. It provides public information on a medicine, including how it was assessed by EMA reflecting the scientific conclusions and the history of the assessment [37].

US review memorandums were published to provide all the emergency use authorization application details, assessment history, product information, related regulatory submissions, and the summary of clinical data.

Eudralex is a collection of rules and regulations which govern medicinal products in European Union. It comprises of many volumes including legislations for veterinary use and other volumes related to all the guidelines [41].

The Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) is the codification of the general and permanent rules published in the Federal Register by the departments and agencies of the Federal Government. While the United States Code is a consolidation and codification by subject matter of the general and permanent laws of the United States. It is prepared by the Office of the Law Revision Counsel of the United States House of Representatives.

Abbreviations

- BLA:

-

Biological License Application

- CFR:

-

Code of Federal Regulations

- CHMP:

-

Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use

- EC:

-

European Commission

- EMA:

-

European Medicines Agency

- EPAR:

-

European Public Assessment Report

- EU:

-

European Union

- EUA:

-

Emergency Use Authorization

- IND:

-

Investigational New Drug

- MA:

-

Marketing Authorization

- MAH:

-

Marketing Authorization Holder

- NDA:

-

New Drug Application

- NME:

-

New molecular entity

- PRIME:

-

Priority medicines scheme

- US:

-

United States

- USC:

-

United States Code

- USFDA:

-

United States Food and Drug Administration

References

World Health Organization. Archived: WHO timeline—Covid-19. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/27-04-2020-who-timeline---covid-19.

European Medicines Agency. Covid-19 vaccines: authorised. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/public-health-threats/coronavirus-disease-covid-19/treatments-vaccines/vaccines-covid-19/covid-19-vaccines-authorised#authorised-covid-19-vaccines-section

European Medicines Agency. Covid-19 treatments: authorised. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/public-health-threats/coronavirus-disease-covid-19/treatments-vaccines/treatments-covid-19/covid-19-treatments-authorised

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency use authorization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) vaccines and drugs and non-vaccine biological products. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/mcm-legal-regulatory-and-policy-framework/emergency-use-authorization

Moore TJ, Furberg CD. Development times, clinical testing, postmarket follow-up, and safety risks for the new drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. J Am Med Assoc Intern Med. 2014;174(1):90.

US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry expedited programs for serious conditions—drugs and biologics. May 2014. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/86377/download

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency use authorization of medical products and related authorities guidance for industry and other stakeholders. January 2017. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/emergency-use-authorization-medical-products-and-related-authorities

European Medicines Agency. Guideline on the scientific application and the practical arrangements necessary to implement Commission Regulation (EC) No 507/2006 on the conditional marketing authorisation for medicinal products for human use falling within the scope of Regulation (EC) No 726/2004. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/draft-guideline-scientific-application-practical-arrangements-necessary-implement-regulation-ec-no/2006-conditional-marketing-authorisation-medicinal-products-human-use-falling_en.pdf

European Medicines Agency. Guideline on procedures for the granting of a marketing authorisation under exceptional circumstances, pursuant to Article 14 (8) of Regulation (ec) no 726/2004. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/guideline-procedures-granting-marketing-authorisation-under-exceptional-circumstances-pursuant/2004_en.pdf

European Medicines Agency. Guideline on the scientific application and the practical arrangements necessary to implement the procedure for accelerated assessment pursuant to Article 14(9) of Regulation (EC) No 726/2004. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-scientific-application-practical-arrangements-necessary-implement-procedure-accelerated/2004_en.pdf

European Medicines Agency. Enhanced early dialogue to facilitate accelerated assessment of Priority Medicines (PRIME). Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/enhanced-early-dialogue-facilitate-accelerated-assessment-priority-medicines-prime_en.pdf

European Medicines Agency. Guidance for applicants seeking access to PRIME scheme. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/european-medicines-agency-guidance-applicants-seeking-access-prime-scheme_en.pdf

Boucaud-Maitre D, Altman JJ. Do the EMA accelerated assessment procedure and the FDA priority review ensure a therapeutic added value? 2006–2015: a cohort study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;72(10):1275–81.

Hwang TJ, Ross JS, Vokinger KN, Kesselheim AS. Association between FDA and EMA expedited approval programs and therapeutic value of new medicines: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;371: m3434.

Alqahtani S, Seoane-Vazquez E, Rodriguez-Monguio R, Eguale T. Priority review drugs approved by the FDA and the EMA: time for international regulatory harmonization of pharmaceuticals? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24(7):709–15.

Kuhler TC, Bujar M, McAuslane N, Liberti L. To what degree are review outcomes aligned for new active substances (NASs) between the European Medicines Agency and the US Food and Drug Administration? A comparison based on publicly available information for NASs initially approved in the time period 2014 to 2016. BMJ Open. 2019;9:11.

Nhamo G, Sibanda M. Forty days of regulatory emergency use authorisation of COVID-19 vaccines: Interfacing efficacy, hesitancy and SDG target 3.8. Glob Public Health. 2021;16(10):1537–58.

Hitti FL, Weissman D. Debunking mRNA vaccine misconceptions—an overview for medical professionals. Am J Med. 2021;134(6):703–4.

Kreps SE, Goldfarb JL, Brownstein JS, Kriner DL. The relationship between US adults’ misconceptions about COVID-19 vaccines and vaccination preferences. Vaccines. 2021;9(8):901.

Kesselheim AS, Darrow JJ. FDA designations for therapeutics and their impact on drug development and regulatory review outcomes. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;97(1):29–36.

Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act FFDCA §505. Federal food, drug, and cosmetic act FFDCA §505. Page: 184–198. Available from: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/COMPS-973/pdf/COMPS-973.pdf

Code of Federal Regulations. Title 21—Chapter I—Subchapter D—Part 314—Subpart D FDA action on applications and abbreviated applications. Available from: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-D/part-314/subpart-D

Code of Federal Regulations. Title 21—Chapter I—Subchapter F Biologics—Part 601 Licensing. Available from: https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=b89a09fffee25804c5e8b814b110c2c0&mc=true&node=pt21.7.601&rgn=div5

Kesselheim AS, Wang B, Franklin JM, Darrow JJ. Trends in utilization of FDA expedited drug development and approval programs, 1987–2014: cohort study. BMJ. 2015;351: h4633.

Kantor A, Haga SB. The potential benefit of expedited development and approval programs in precision medicine. J Person Med. 2021;11:1.

Liberti L, Bujar M, Breckenridge A, Hoekman J, McAuslane N, Stolk P, et al. FDA facilitated regulatory pathways: visualizing their characteristics, development, and authorization timelines. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:161.

Courtney B, Sherman S, Penn M. Federal legal preparedness tools for facilitating medical countermeasure use during public health emergencies. J Law Med Ethics. 2013;41(Suppl 1):22–7.

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency use authorization. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/mcm-legal-regulatory-and-policy-framework/emergency-use-authorization

US Food and Drug Administration. What are medical countermeasures? Available from: https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/about-mcmi/what-are-medical-countermeasures

European Commission. EudraLex—Volume 1—Pharmaceutical legislation for medicinal products for human use. Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 November 2001 on the community code relating to medicinal products for human use. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:02001L0083-20190726

European Commission. EudraLex—Volume 1—Pharmaceutical legislation for medicinal products for human use. Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 March 2004 laying down community procedures for the authorisation and supervision of medicinal products for human and veterinary use and establishing a European Medicines Agency. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:02004R0726-20190128

European Commission. EudraLex—Volume 1—Pharmaceutical legislation for medicinal products for human use. Commission Regulation (EC) No 507/2006 of 29 March 2006 on the conditional marketing authorisation for medicinal products for human use falling within the scope of Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32006R0507

Boon WP, Moors EH, Meijer A, Schellekens H. Conditional approval and approval under exceptional circumstances as regulatory instruments for stimulating responsible drug innovation in Europe. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88(6):848–53.

Hoekman J, Boon W. Changing standards for drug approval: a longitudinal analysis of conditional marketing authorisation in the European Union. Soc Sci Med. 2019;222:76–83.

US Food and Drug Administration. Drugs@FDA: FDA-approved drugs. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/

US Food and Drug Administration. Licensed biological products with supporting documents. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/licensed-biological-products-supporting-documents

European Medicines Agency. European public assessment reports: background and context. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/what-we-publish-when/european-public-assessment-reports-background-context#:~:text=A%20European%20public%20assessment%20report%20(EPAR)%20is%20published%20for%20every,or%20refused%20a%20marketing%20authorisation.&text=An%20EPAR%20provides%20public%20information,it%20was%20assessed%20by%20EMA.

Eudralex—Volume 1—Pharmaceutical legislation for medicinal products for human use. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/health/medicinal-products/eudralex/eudralex-volume-1_en

eCFR—Title 21 of code of federal regulations. Available from: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21

United States Code. Office of the law revision counsel. Available from: https://uscode.house.gov/browse/prelim@title21&edition=prelim

EudraLex—EU legislation. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/health/medicinal-products/eudralex_en

US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry—providing clinical evidence of effectiveness for human drug and biological. May 1998. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Providing-Clinical-Evidence-of-Effectiveness-for-Human-Drug-and-Biological-Products..pdf

Faden LB, Kaitin KI. Assessing the performance of the EMEA’s centralized procedure: a comparative analysis with the US FDA. Drug Inf J. 2008;42(1):45–56.

Joppi R, Bertele V, Vannini T, Garattini S, Banzi R. Food and drug administration vs European medicines agency: review times and clinical evidence on novel drugs at the time of approval. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;86(1):170–4.

European Medicines Agency CPMP. Points to consider on application with 1. Meta-analyses; 2. One pivotal study. May 2001. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/points-consider-application-1meta-analyses-2one-pivotal-study_en.pdf

Downing NS, Aminawung JA, Shah ND, Krumholz HM, Ross JS. Clinical trial evidence supporting FDA approval of novel therapeutic agents, 2005–2012. J Am Med Assoc. 2014;311(4):368–77.

Morant AV, Vestergaard HT. European marketing authorizations granted based on a single pivotal clinical trial: the rule or the exception? Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;104(1):169–77.

Leyens L, Richer E, Melien O, Ballensiefen W, Brand A. Available tools to facilitate early patient access to medicines in the EU and the USA: Analysis of conditional approvals and the implications for personalized medicine. Public Health Genom. 2015;18(5):249–59.

European Medicines Agency. EMA initiatives for acceleration of development support and evaluation procedures for COVID-19 treatments and vaccines. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/ema-initiatives-acceleration-development-support-evaluation-procedures-covid-19-treatments-vaccines_en.pdf

World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (Covid-19) dashboard. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/.

World Health Organization. Off-label use of medicines for Covid-19. March 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/off-label-use-of-medicines-for-covid-19.

Durán CE, Cañás M, Urtasun MA, Elseviers M, Andia T, Vander Stichele R, et al. Regulatory reliance to approve new medicinal products in Latin American and Caribbean countries. Revista Panamericana de Salud Publica/Pan American Journal of Public Health. 2021;45: e10.

Saidu Y, Angelis D, Aiolli S, Gonnelli S, Georges AM. A review of regulatory mechanisms used by the WHO, EU, and US to facilitate access to quality medicinal products in developing countries with constrained regulatory capacities. Therap Innov Regul Sci. 2013;47(2):268–76.

Moran M, Strub-Wourgaft N, Guzman J, Boulet P, Wu L, Pecoul B. Registering new drugs for low-income countries: the african challenge. Public Library Sci (PLoS Med). 2011;8(2): e1000411.

Congressional Research Service. Global economic effects of Covid-19. November 2021. Available from: https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/R46270.pdf

US Food and Drug Administration. Fast track. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/patients/fast-track-breakthrough-therapy-accelerated-approval-priority-review/fast-track.

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization Letter—Pfizer- BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine/[Comirnaty]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/150386/download

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for an Unapproved Product Review Memorandum—Pfizer- BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine/[Comirnaty]. [Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/144416/download

European Medicines Agency. European Public Assessment report—Comirnaty. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/comirnaty-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization Letter –Janssen COVID-19 Vaccine. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/146303/download

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for an Unapproved Product Review Memorandum—Janssen COVID-19 Vaccine. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/146338/download

European Medicines Agency. European Public Assessment report—COVID-19 Vaccine Janssen. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/covid-19-vaccine-janssen-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization Letter—Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine/[Spikevax]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/144636/download

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for an Unapproved Product Review Memorandum—Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine/[Spikevax]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/144673/download

European Medicines Agency. European Public Assessment report—COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/spikevax-previously-covid-19-vaccine-moderna-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization Letter—Casirivimab co-packaged with Imdevimab /[REGEN-COV]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/145610/download

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) CDER Review—Casirivimab and Imdevimab /[REGEN-COV]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/145610/download

European Medicines Agency. European Public Assessment report—Ronapreve. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/ronapreve-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization Letter—Remdesivir/[Veklury]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/137564/download

US FDA Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for an Unapproved Product CDER Review Memorandum—Remdesivir/[Veklury]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/155772/download

European Medicines Agency. European Public Assessment report—Veklury. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/veklury-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization Letter—Sotrovimab/[Xevudy]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/149532/download

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) CDER Review Memorandum—Sotrovimab/[Xevudy]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/150130/download

European Medicines Agency. European Public Assessment report—Xevudy. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/xevudy-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization Letter—Nirmatrelvir co-packaged with ritonavir/[Paxlovid]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/155049/download

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) CDER Review Memorandum—Nirmatrelvir co-packaged with ritonavir/[Paxlovid]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/155194/download

European Medicines Agency. European Public Assessment Report—Paxlovid. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/paxlovid-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization Letter—Tocilizumab/[Actemra]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/150319/download

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for the Unapproved Use of an Approved Product CDER Review—Tocilizumab/[Actemra]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/150748/download

European Medicines Agency. European Public Assessment report—RoActemra. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/variation-report/roactemra-h-c-955-ii-0101-epar-assessment-report-variation_en.pdf

European Medicines Agency. European Public Assessment report—COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/vaxzevria-previously-covid-19-vaccine-astrazeneca-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf

European Medicines Agency. European Public Assessment report—Nuvaxovid. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/covid-19-vaccine-janssen-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf

European Medicines Agency. European Public Assessment report—Kineret. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/variation-report/kineret-h-c-000363-ii-0086-epar-assessment-report-variation_en.pdf

European Medicines Agency. European Public Assessment report—Regkinora. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/regkirona-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization Letter—Molnupiravir. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/155053/download

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) CDER Review Memorandum—Molnupiravir Capsules. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/155241/download

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization Letter—Tixagevimab co-packaged with Cilgavimab/[Evusheld]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/154704/download

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) CDER Review Memorandum—Tixagevimab co-packaged with Cilgavimab Injection for Intramuscular Use/[Evusheld]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/155107/download

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization Letter—Bamlanivimab + Etesevimab. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/145801/download

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) CDER Review Memorandum—Bamlanivimab 700 mg and Etesevimab 1400 mg IV Administered Together. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/146255/download

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization Letter—Baricitinib/[Olumiant]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/143822/download

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for the Unapproved Use of an Approved Product CDER Review Memorandum—Baricitinib/[Olumiant]. [Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/144473/download

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization Letter—COVID-19 convalescent plasma. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/141477/download

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) Clinical Review Memorandum—COVID-19 convalescent plasma. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/141480/download

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) CDER Review Memorandum—Bebtelovimab. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/156396/download?attachment

US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization Letter—Bebtelovimab. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/156151/download

US Food and Drug Administration. Summary Basis for Regulatory Action—Pfizer- BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine/[Comirnaty]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/151733/download

US Food and Drug Administration. Summary Basis for Regulatory Action—Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine/[Spikevax]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/155931/download

US Food and Drug Administration. CDER Summary Review—Remdesivir/[Veklury]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2020/214787Orig1s000Sumr.pdf

European Commission. EudraLex—Volume 1—Pharmaceutical legislation for medicinal products for human use. Regulation (EC) No 1901/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 December 2006 on medicinal products for paediatric use and amending Regulation (EEC) No 1768/92, Directive 2001/20/EC, Directive 2001/83/EC and Regulation (EC) No 726/2004. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32006R1901

European Commission. EudraLex—Volume 1—Pharmaceutical legislation for medicinal products for human use. Regulation (EC) No 1394/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 November 2007 on advanced therapy medicinal products. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32007R1394

European Commission. EudraLex—Volume 1—Pharmaceutical legislation for medicinal products for human use. Commission Regulation (EC) No 1234/2008 of 24 November 2008 concerning the examination of variations to the terms of marketing authorisations for medicinal products for human use and veterinary medicinal products. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:02008R1234-20210513

European Commission. EudraLex—Volume 1—Pharmaceutical legislation for medicinal products for human use. Commission Regulation (EC) No 1662/95 of 7 July 1995 laying down certain detailed arrangements for implementing the Community decision-making procedures in respect of marketing authorizations for products for human or veterinary use. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:31995R1662

Code of Federal Regulations—Title 21—Chapter I—Subchapter D Drugs for human use—Part 314 Applications for FDA approval to market a new drug. Available from: https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=55b50bcde68e57fc4a6a50aeeb6edf76&mc=true&node=pt21.5.314&rgn=div5

US Code—Title 21—Chapter 9 Federal Food, Drug, And Cosmetic Act—Subchapter V—Part A—Section 355 New drugs. Available from: https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title21-section355&num=0&edition=prelim

US Code—Title 42—Chapter 6A — Public Health Service—Subchapter II—Part F Licensing of biological products and clinical laboratories. Available from: https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title42/chapter6A/subchapter2/partF/subpart1&edition=prelim

US Code—Title 21—Chapter 9 Federal Food, Drug, And Cosmetic Act—Subchapter V—Part A—Section 356 Expedited approval of drugs for serious or life-threatening diseases or conditions. Available from: https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title21-section356&num=0&edition=prelim

US Code—Title 21—Chapter 9 Federal Food, Drug, And Cosmetic Act—Subchapter V—Part A—Section 356b Reports of post marketing studies. Available from: https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title21-section356b&num=0&edition=prelim

US Code—Title 21—Chapter 9 Federal Food, Drug, And Cosmetic Act—Subchapter V—Part E—Section 360bbb-3 Authorization for medical products for use in emergencies. Available from: https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title21-section356&num=0&edition=prelim

US Code—Title 21—Chapter 9 Federal Food, Drug, And Cosmetic Act—Subchapter V—Part E—Section 360bbb-3c Expedited development and review of medical products for emergency uses. Available from: https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title21-section360bbb-3c&num=0&edition=prelim

US Code—Title 21—Chapter 9 Federal Food, Drug, And Cosmetic Act—Subchapter V—Part E—Section 360bbb-4a Priority review to encourage treatments for agents that present national security threats. Available from: https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title21-section360bbb-4a&num=0&edition=prelim

US Code—Title 21—Chapter 9 Federal Food, Drug, And Cosmetic Act—Subchapter VII—Part C—Subpart 2 Fees relating to drugs—Sections 379g to 379h-2. Available from: https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title21/chapter9/subchapter7/partC/subpart2&edition=prelim

Congressional Research Service. Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA): 2017 Reauthorization as PDUFA VI. Available from: https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R44864.pdf

US Food and Drug Administration. Drugs@FDA glossary of terms. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/drugsfda-glossary-terms

European Medicines Agency. Glossary of regulatory terms. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/about-us/about-website/glossary/name_az/E

Funding

No funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The following are the contributions for each author: MG contributed to conception, design, analysis, interpretation of data, drafting, and revising. ES contributed to supervision and directing in designing, analysis, interpretation, and drafting.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghadanian, M., Schafheutle, E. Comparison between European Medicines Agency and US Food and Drug Administration in Granting Accelerated Marketing Authorizations for Covid-19 Medicines and their Utilized Regulations. Ther Innov Regul Sci 58, 79–113 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43441-023-00574-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43441-023-00574-6