Abstract

In their recent article “A Gendered Resource Curse? Mineral Ownership, Female Unemployment and Domestic Violence in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Mario Krauser, Tim Wegenast, Gerald Schneider, and Ingeborg Elgersmar argue that international mine ownership alters employment possibilities for women in comparison to domestically-owned mines. They make the case that this also alters gender norms and find that foreign ownership decreases domestic violence reporting from women. In this reply, I take a closer look at the proposed mechanisms that local gender norms change around international mines and will review literature that finds persisting effects of gender norms on gender equality. Finally, I will assess the circumstance under which norms may change in response to outside interventions and suggest avenues for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

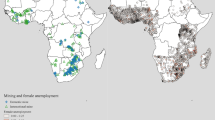

How does mineral extraction affect gender equality? In their recent article “A Gendered Resource Curse? Mineral Ownership, Female Unemployment and Domestic Violence in Sub-Saharan Africa,” published in this journal, Mario Krauser, Tim Wegenast, Gerald Schneider, and Ingeborg Elgersmar (henceforth Krauser et al.) assess whether the difference in mineral ownership – domestic vs. international – can explain variation in the effect of mines on gendered (un)employment as well as domestic violence experienced by women.

Their theory posits that locally-owned mines employ local males, while internationally-owned mines bring in foreign workers, with little employment opportunities for the local male population. Hence, domestically-owned mines should increase the employment of local males, which, in turn, does not interfere with the “male breadwinner” norm of households around this mine.

However, international mines introduce a “structural labor market shift,” affecting the females differently: while the authors expect that unemployment rises for local males per se, female employment is affected in two ways. First—due to the degradation of land around mines—women deviate from subsistence farming and move toward the service sector. Second, the authors argue that nevertheless, the overall unemployment of women increases, due to the limited number of jobs provided for local females by international firms.

Based on their theory on gendered labor market effects, their argument extends to domestic violence. At the heart of this argument lies the change in gender norms, which—through (the potential of) economic and monetary gains of females in the presence of internationally-owned mines—induces empowerment and decreases intimate partner violence directed against women.

Krauser et al.’s contribution to distinguish between types of mine ownership is a timely and important addition to the debate whether natural resources are an impediment or a furtherance of gender equality and female empowerment (e.g., Kotsadam et al. 2017; Rustad et al. 2016; Kotsadam and Tolonen 2016; Cools and Kotsadam 2017). In this reply, I will shed light on the central (but unmeasured) aspect that links mine ownership to domestic violence: local gender norms. As I will show, these norms—even if altered—often have persistent effects on gender equality. I argue that to answer the critical question of how gender norms change and lead to more gender equality, we need to include knowledge about variation in gender norms before (and after) outside actors enter the labor market. More generally, it will be critical for future research to show how the interrelationship between local norms and external interventions affect gender equality.

2 A Gendered Effect?

Krauser et al. examine the labor market effects of international vs. domestic mine ownership and propose that this distinction is responsible for gendered effects of the mining industry. Mines pose a problem for women who work in subsistence farming—the soil degrades in the areas of mines. Yet while international mine ownership does not create job opportunities for males, the authors argue, the job market for females shifts structurally with new employment opportunities, ultimately fostering an empowerment mechanism that leads to less domestic violence.

Let us examine the effects of Krauser et al. in detail: While mines do have opposite effects on the female vs. the male labor market with no differentiation between mine ownership (Table 3), the picture is less gendered once international and domestic mines are introduced as separate variables. As hypothesized, when international mines reach statistical significance, they increase unemployment for both genders (Table 4) or females only (Table 1, with no statistically significant effect on male unemployment). Similarly, when domestic mines reach statistical significance, they reduce unemployment for both genders (Table 1) or males only (Table 4, with no statistically significant effect on female unemployment).

Hence, the gendered effect we observe is that sometimes mines do not affect female or male unemployment when it affects the other gender. Considering unemployment only, the hypotheses and empirical evidence do not point towards a strong gendered effect of mine ownership.

Moving beyond unemployment, do international mines induce a structural shift for females? The authors assess female labor market conditions more closely and find that around international mines, women work in the service sector more often than being occupied by agricultural work. Although we still observe more unemployment for women, on the whole, this could indeed increase their cash income for those in the service sector.Footnote 1

It is precisely this mechanism which, according to the authors, results in a shift from “male breadwinner” models to female empowerment. Central to the theory of Krauser et al. is that domestic mines perpetuate local gender norms and that international mines shift these norms via the labor market that empowers women economically. At the end of this causal chain, Krauser et al. empirically find that women around international mines report that they experience less intimate partner violence.

While women could indeed profit from international mining, there are two potential issues with this finding. On the one hand, the finding that women around international mines report less domestic violence could be the result of the process of reporting in and by itself. On the other hand, the analysis cannot account for the dynamics in gender norms with the present data, which I will discuss more thoroughly in the next section.

The reporting of interpersonal violence can be subject to biases. In particular, this may be the case with sensitive issues – such as violence – and female empowerment. In an analysis of women’s political representation in India, Iyer et al. (2012) find that reporting of crime is more likely when there are female representatives.

Empowerment may, thus, lead to more reporting of the existing violence, even if it reduces violence in the population. In consequence, one might have to reconsider the reporting effects of mines and whether international mines lead to less reported violence, to begin with. One alternative explanation is offered by two of the authors in another publication: international mines could drive violent conflict and thus foster state repression (Wegenast and Schneider 2017), which could affect the likelihood of women to speak up about violence in the first place.

3 Local Gender Norms: Persistence and Change

Can internationally-owned mines alter gender norms via the labor market? Krauser et al. are not the first to propose that gender norms are the mechanism linking natural resources and gender equality. Yet, the article does not empirically account for these norms and other contributions to the field only approximate these norms by using indicators on the acceptance of domestic violence (cf. Kotsadam and Tolonen 2016; Kotsadam et al. 2017). Norms that are manifested in gendered institutions as well as their actual shifts are not taken into consideration.

3.1 The Persistent Effect of Local Gender Norms

Local gender norms—such as inheritance rights, polygyny, and matrilineality—have critical social effects (e.g., Koos and Neupert-Wentz 2019; Robinson and Gottlieb 2019). In particular, these norms frequently have long-lasting effects on gender equality, which may persist long after the norms have been altered.

In a study that directly links to the theory proposed by Krauser et al., Alesina, Giuliano, and Nunn (2013)—test Ester Boserup’s (1970) theory that variation in the agricultural sector in the pre-industrial era accounts for gender equality today. Specifically, Alesina, Giuliano, and Nunn (2013) find that plough agriculture—which was mainly practiced by men—led to a gendered division of labor and adheres to less equal gender norms today. At the same time, shifting cultivation that didn’t depend on the plough but handheld tools—which was also practiced by women—led to female integration in the labor market and adheres to more equal gender norms today.

Contrary to Krauser et al.’s expectations, in which female participation in agriculture sustains the “male breadwinner” model, women are treated more equally and have better political representation, where they participated in agricultural activities. Furthermore, this also gives evidence on how the historical development of gender norms affects gender equality today.

The persistent effects of gender norms have been documented for different types of norms across contexts. Focusing on local inheritance norms in Germany around 1800, Hager and Hilbig (2019) report an ongoing positive effect of equal inheritance, in which inheritance is divided among siblings rather than given to the firstborn son, on the local election of females.

Robinson and Gottlieb (2019) show a similar effect of local gender norms on political participation on the African continent. They examine the effect of kinship systems—measured around or before European colonization—on female political participation. Their findings suggest that matrilineality—family membership derived through the mother’s lineage—persistently adheres to progressive gender norms, enhancing gender equity and female political participation in contrast to patrilineal systems.

3.2 Do Local Gender Norms Change in Response to Outside Interventions?

Given that this research points towards the persistent, long-term effect of gender norms, do these norms change in response to the presence or intervention of outside actors? Such interventions and changes may include the presence of international mines, development interventions, interventions targeted at gender equality, civil war, and the introduction of new state norms.

The literature has only started to appreciate this triangular relationship between local norms, gender equality, and outside influence. In theory, the present local gender norms could determine whether changes in the political environment lead to empowerment or a backlash that could even harm women (cf. Guarnieri and Rainer 2018)—a theoretical mechanism that is also considered by Krauser et al. (p. 7–8).

In a survey experiment, Muriaas et al. (2019) analyze the effect of the endorsement of a policy intervention on public support of child marriages. The authors observe a backlash effect of policy endorsements against child marriage for all messengers but female traditional authorities. In particular, female traditional authorities are effective in changing the support of the protection against child marriages in matrilineal kinship systems, and when women receive the endorsement.

Given these potential unintended consequences of policy endorsements, they conclude that “[r]ights concerning gender equality, sexuality, and reproduction are policy areas that are sensitive to prior beliefs and backfire effects” (Muriaas et al. 2019, p. 1907). Hence female empowerment may hinge on local gender norms prior to the intervention (e.g., matrilineality) and the policymaker (the messenger or type of intervention).

Yet, interventions not targeted at gender equality can also affect changes in gender norms. Lazarev (2019) finds a disruptive effect of armed conflict on the patriarchal order in Chechnya. As a result of the conflict, he finds that women strategically choose state law over Sharia and customary law, a finding that has also been observed in other contexts, such as Papua New Guinea (cf. Cooper 2019). The more severe the conflict, the more women use state law, which is less discriminatory towards them and can be read as a key to empowerment. Similar to Krauser et al., Lazarev argues that due to the conflict, women become the “principal breadwinners in their families” (Lazarev 2019, p. 674), boosting their within-household bargaining power.

However, given the patriarchal societal order prior to the conflict, Lazarev (2019) also observes a backlash of female-empowerment through the “semiformal introduction of polygamy, support for the practice of honor killings, and restrictions on women’s dress” (Lazarev 2019, p. 699). In particular, none of the police officers Lazarev interviewed “considered domestic violence to be a crime, and none thought that a police officer had an obligation to intervene in a case of wife beating” (Lazarev 2019, p. 700).

4 Conclusion

The findings in this literature show that in order to investigate if outside disruptions, interventions, or investments change norms that are responsible for (the lack of) empowerment of women, we need to analyze the variation in norms as well as the type of intervention. The article by Krauser et al. contributes in exploring patterns of how the ownership of mines may affect genders differently and ultimately affects their equality. Yet, the stipulated causal mechanism might be regarded with caution, if we examine more closely the long-lasting effect of gender norms.

Knowledge of norms prior to potential norm-disruptions is necessary to assess whether a change in local gender norms is responsible for the effects of gender equality and intimate partner violence. The types of local gender norms can have varying effects on gender equality. For instance, there could be considerable differences between inheritance norms, marriage customs, and traditional harmful practices, such as female genital cutting.

Furthermore, the type of outside changes may moderate the effects of gender norms differently. Development interventions targeted at gender equality—such as in the case of Muriaas et al. (2019) – could be substantially different in their effect than other types of disruptions, such as international investments (Krauser et al.) or war (Lazarev 2019). In consequence, both the type of gender norms present, as well as the type of outside intervention, are varying factors that need to be theorized and analyzed in subsequent research.

Lastly, time is an important factor to consider. While disruptions and interventions open a window of opportunity in the change of norms that allow for empowerment and subsequent gender equality, norms also change slowly and may develop differently over time. Although shifts are possible in response to disruptions and interventions, norms pertaining to gender can change, but may not do so easily. It will be particularly important for future research to identify the short-, mid-, and long-term effects of these changes. As foreshadowed by Lazarev (2019), initial moves towards women empowerment in the short term can be relegated in the long-term. At the same time, some gender norms will take long to develop until they take effect in altering opportunities for women.

It will, therefore, be essential to analyze the gender norms, their persistent effects, and if and how they change in response to outside interventions. Furthermore, when norms do change, we need to acquire knowledge whether and how these sustain.

Notes

To make the case of a relative household position of females around international mines, it would be helpful to see if this effect is not present for males.

References

Alesina, Alberto, Paola Giuliano, and Nathan Nunn. 2013. On the origins of gender roles: women and the plough. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 128(2):469–530.

Boserup, Ester. 1970. Woman’s role in economic development. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd.

Cools, Sara, and Andreas Kotsadam. 2017. Resources and intimate partner violence in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Development 95:211–230.

Cooper, Jasper. 2019. “State capacity and gender inequality: experimental evidence from Papua New Guinea.” Working Paper. http://jasper-cooper.com/papers/Cooper_CAP.pdf. Accessed: 10.01.2020

Guarnieri, Eleonora, and Helmut Rainer. 2018. “Female empowerment and male backlash.” CESifo working paper series 7009 (CESifo group munich). https://ideas.repec.org/p/ces/ceswps/_7009.html. Accessed: 10.01.2020

Hager, Anselm, and Hanno Hilbig. 2019. Do inheritance customs affect political and social inequality? American Journal of Political Science https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12460.

Iyer, Lakshmi, Anandi Mani, Prachi Mishra, and Petia Topalova. 2012. The power of political voice: women’s political representation and crime in India. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 4(4):165–193.

Koos, Carlo, and Clara Neupert-Wentz. 2019. Polygynous neighbors, excess men, and intergroup conflict in rural Africa. Journal of Conflict Resolution 64(2-3):402-431 https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002719859636.

Kotsadam, Andreas, and Anja Tolonen. 2016. African mining, gender, and local employment. World Development 83:325–339.

Kotsadam, Andreas, Gudrun Østby, and Siri Aas Rustad. 2017. Structural change and wife abuse: a disaggregated study of mineral mining and domestic violence in sub-Saharan Africa, 1999–2013. Political Geography 56:53–65.

Lazarev, Egor. 2019. Laws in conflict: legacies of war, gender, and legal pluralism in Chechnya. World Politics 71(4):667–709.

Muriaas, Ragnhild L., Vibeke Wang, Lindsay Benstead, Boniface Dulani, and Lise Rakner. 2019. Why the gender of traditional authorities matters: intersectionality and women’s rights advocacy in malawi. Comparative Political Studies 52(12):1881–1924. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414018774369.

Robinson, Amanda Lea, and Jessica Gottlieb. 2019. How to close the gender gap in political participation: lessons from matrilineal societies in Africa. British Journal of Political Science https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123418000650.

Rustad, Siri Aas, Gudrun Østby, and Ragnhild Nordås. 2016. Artisanal mining, conflict, and sexual violence in Eastern DRC. The Extractive Industries and Society 3(2):475–484.

Wegenast, Tim, and Gerald Schneider. 2017. Ownership matters: natural resources property rights and social conflict in Sub-Saharan Africa. Political Geography 61:110–122.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Neupert-Wentz, C. Local Gender Norms: Persistence or Change? Reply to “A Gendered Resource Curse? Mineral Ownership, Female Unemployment and Domestic Violence in Sub-Saharan Africa” by Mario Krauser, Tim Wegenast, Gerald Schneider, and Ingeborg Elgersmar. Z Friedens und Konflforsch 9, 219–225 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42597-020-00026-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42597-020-00026-0