Abstract

Coral cover throughout the Caribbean region has declined by approximately 80% since the 1970s (Gardner et al. in Ecology 86(1):174–184, 2005) attributed to a combination of environmental and anthropogenic factors, including ocean acidification, rising sea surface temperatures, increased susceptibility to disease, as well as increased frequency and strength of storms, development stress, and increased sediment and nutrient loads. Three Global Bleaching Events (GBE) coincide directly with El Niño warming phases in El Niño-Southern Oscillation cycle (1997–1998, 2009–2010, and 2014–2017). This study focuses the effects of anomalously high sea surface temperatures on Turks and Caicos Islands coral taxa during the 2014–2017 GBE. Interannual and interspecific variability in coral health offshore of South Caicos Island were evaluated between 2012 and 2018 using the CoralWatch citizen science Coral Health Chart method along belt transects at four dive survey sites. The study includes 104 site surveys conducted from 15 October 2012 to 18 July 2018. Coral health was assessed for the 35 principal coral taxa and 5646 individual corals. Data indicates that all coral taxa at the study sites were resilient to the maximum regional thermal stress during the 2014–2017 GBE, with boulder-type corals showing no significant bleaching as a result of the peak thermal stress in late 2015 and plate-type corals responding with a significant (p < 0.05) bleaching signal (i.e., coral color reductions), rebounding to pre-GBE pigmentations within months of the anomalously-high thermal stress. Boulder coral types were significantly healthier in 2017 than in 2014 when using coral color as a health diagnostic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Climate-change induced increases in sea surface temperatures (SSTs) and the frequency of extreme thermal stress events have resulted in widespread coral bleaching [1,2,3,4,5,6]. For instance, when SSTs surpass a coral’s thermal threshold, bleaching may occur. Coral bleaching mechanisms are linked with the unique endosymbiotic relationship between the host coral and single-celled dinoflagellates known as Symbiodinium (zooxanthellae), living within the coral polyps that provide corals with their color and 90% of their total energy through photosynthesis [7]. When corals become stressed, they expel their algal symbionts, losing both their pigmentation and primary source of nutrients [7, 8].

Approximately 90% of Caribbean coral reef systems are likely to experience severe bleaching in response to climate-change induced thermal stress by 2040 [9,10,11]. Over the past three decades, coral cover throughout the Caribbean has declined by approximately 80% [12]. Health declines of these reef biomes are largely attributable to major Global Bleaching Events (GBEs) that have occurred most recently in 1997–1998, 2009–2010, and 2014–2017, coinciding with El Niño warming phases in the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle [2, 6, 13]. Lough et al. [14] found that the level of thermal stress on coral reefs was about 3 times greater in the GBE of 1997–1998 than the level of thermal stress in pre-industrial El Niño of 1878, hinting that temperatures have been rising steadily with the Caribbean and Atlantic oceans experiencing the most severe stress. Although thermal stress in the Caribbean has been influencing coral health in years outside of major GBEs, the 2014–2017 event was detrimental to Caribbean reef ecosystems, particularly given the two extreme hurricanes in 2017 that damaged both shallow and deep reefs by dislodging coral colonies and turning them to rubble [15].

Seasonality of the environmental stressors, such as increases in water temperature, may impact coral susceptibility to bleaching [16]. Symbiont density responds to higher water temperatures negatively causing decreases in Symbiodinium [16]. However, recent studies reveal that the specific lineages, or clades, of Symbiodinium may influence the resistance and abilities of individual coral taxa to recover from environmental and thermal stress [7, 17]. Consequently, when evaluating the resistance of coral taxa and reefs to thermal stress, it is important to consider the multiple environmental, geographical, and physiological factors that can impact coral resistance and recovery from stress events such as the recent 2014–2017 GBE.

With SSTs predicted to increase in the coming years, a simple methodology of determining coral health is vital to gain a wide-spread assessment of bleaching and recovery [10]. The CoralWatch (CW) citizen science monitoring program enables non-specialists to assess coral health using a color chart (Fig. 1), providing a health diagnostic tool with the potential to expand global coral bleaching and health datasets, providing a low-cost proxy for evaluating and documenting natural coral color variability and health [18]. CW color health charts have been used in over 25 published scientific papers to help validate, in part, remotely-sensed methods of monitoring thermal stress and coral bleaching threats [19]. Following Siebeck et al. [20], CW coral health score, CWHS, can be used as a diagnostic to monitor coral health over time and coral sensitivity to regional thermal stress. Specifically, lighter CWHS values (closer to 1) represent decreased densities of Symbiodinium associated with stress and bleaching, while darker CWHS values (closer to 6) represent higher densities of Symbiodinium and therefore healthier or recovering corals [18, 20] (Fig. 1). According to Siebeck et al. [20], a shift in CWHS distributions to lighter color hues over time indicates reductions in zooxanthellae density.

CoralWatch Coral Health Chart sampling methodology, used to sample 5646 corals in the Turks and Caicos from 2012 to 2018 over 104 surveys. An example measurement of a darker, healthier coral is depicted, with hue CWHS difference and average shown. Schematic based on “What is coral bleaching?” schematic, published by NOAA (2019)

This study investigates the interannual and interspecific variability in Turks and Caicos coral taxa stress and subsequent recovery, evaluated using the CW Coral Health Chart method, in response to the 2014–2017 Global Bleaching Event. South Caicos Island, historically dominated by Montastraea spp., Siderastrea spp., and Porites spp., has seen a drop in average coral cover from 32.5% in 1995 to 21.9% in 2004 with signs of increased coral bleaching and disease [21]. Compared to neighboring countries in the Caribbean, South Caicos has reasonably healthy reefs, perhaps in part due to lower density tourism and minimal anthropogenic drivers of coral stress [13]. South Caicos Island fringing reefs are characterized as narrow, discontinuous, with shelf-edges dominated with macroalgae, corals, and gorgonians, with the reef dropping off into the deep ocean at approximately 15 meters, as seen in Fig. 1 [13]. As sea surface temperatures continue to rise, susceptibility to bleaching is increasing. This increase in coral bleaching causes physiological distress leading to increased incidence of coral disease, coral death, and growth of macroalgae [22]. It is essential to understand the extent of thermal stress and its impacts on corals around South Caicos so that effective conservation methods may take place.

An assessment of coral color loss and restoration was conducted using 104 surveys of CW coral color variability offshore of South Caicos Island (Fig. 2) for 35 coral taxa from 2012 to 2018, along with NOAA Coral Reef Watch (CRW) monitoring products. Our study questioned if coral color, a coral health proxy, in the Turks and Caicos was significantly affected by the late 2015 thermal stress event as part of the 2014–2017 GBE? In addition, were different coral species in this region more resilient to the 2014–2017 bleaching event? If so, what was the interspecific variability in coral rebound and healing from this major thermal stress event? Specifically, to what extent did corals that survived the 2014 event lose and regain their color? And finally, does coral color decline linearly in response to repeated thermal stress, or are coral color and bleaching stress signals nonlinear and more strongly coupled with longer wavelength regional sea surface temperature (SST) signals?

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Data collection

The CWHS data assessed in this study was collected by students, interns, and researchers at The School for Field Studies Center for Marine Resource Studies (SFS) on South Caicos Island (Fig. 2). Members of the SFS field station assessed coral health using the CoralWatch method (Fig. 1) from 15 October, 2012 to 18 July, 2018 across multiple dive study sites in the Admiral Cockburn Land and Sea National Park off South Caicos Island, TCI. Coral reef sampling locations in this study include four dive sites greater than 10 m in depth, i.e., Arch, Chain, Plane, and Spanish Maze (Fig. 2).

At each study site, a 100 m long line-intercept transect was established as part of SFS’ long-term monitoring of reef health in South Caicos. At 2-m intervals, two corals were randomly selected, the diver recorded the lightest and darkest CWHS values of a coral using the CW color card chart, from which average CWHS for the specific coral species were determined (Fig. 1). Water temperature, time of the day, depth, coral species, and CWHS values were also recorded. CWHS values were then averaged by individual coral species and by coral types (boulder and plate).

2.2 NOAA Coral Reef Watch (CRW) data

NOAA Coral Reef Watch (CRW) products were extracted for the study area to diagnose thermal stress variability over the study period, and to determine when the environmental stress during the 2014–2017 GBE began. Specifically, the 4 coral reef sampling sites in this study are encompassed by two (2) NOAA CRW 5-km grids (0.05°), i.e., NOAA-1 and NOAA-2 grids (Fig. 1). NOAA CRW products from 1985 to 2018, including the 2012–2018 study interval, were extracted to help establish a long-term record of thermal stress in the TCI region, including: (a) SST Anomaly (SSTA), (b) Coral Bleaching HotSpot, and (c) Degree Heating Week (DHW). The Coral Bleaching HotSpot represents the maximum of the monthly mean SST climatology, as outlined by Strong et al. [23], Liu et al. [24], and Skirving et al. [25]. A description of the data products can be found on NOAA’s, “Description for 5 km Regional Virtual Stations, Time Series Data, and Graphs,” webpage (https://coralreefwatch.noaa.gov/vs/description.php).

2.3 Statistical analysis

In order to estimate differences in CWHS over time and to diagnose coral stress and response during and after the 2014–2017 GBE, three time intervals were established using NOAA SSTA data: (1) 28 April, 2014–28 April, 2015–pre-GBE conditions, (2) 28 April 2015–31 October 2016–maximum thermal stress during the GBE as indicated by the SSTA time series, and (3) 1 November 2016–18 July 2017–post GBE recovery time window, corresponding with the return of SSTA levels to pre-GBE conditions.

Gaussian Probability Density Functions (PDFs) of CWHS data for coral species and type were fitted using MATLAB®’s Statistical Toolbox for each of the three-time windows, according to Johnson et al. [26, 27] and Bowman and Azzalini [28]. MATLAB’s Statistics and Machine Learning Toolbox was used to conduct the ANOVA analyses to determine statistical significance of coral color response during and after the 2014–2017 GBE. Using ANOVA, two CWHS distributions were determined to be statistically significant from one another if the ANOVA returned a p value < 0.05.

Interspecific variability coral response to the 2014–2017 GBE was then evaluated by comparing, the change in average CWHS before significant thermal stress impacted the region to the average CWHS during significant thermal stress in the region, as established by the NOAA SSTA data products. Coral species recovery was then compared from the thermal stress after the April 2015 SSTA maximum by quantifying change in average CWHS during the GBE to the average CWHS after significant thermal cooling region.

The average CWHS time series for each coral species was cross-correlated with SSTA in order to understand which coral taxa are most sensitive to changes in water temperature and thermal stress. Cross-correlation coefficients, Rxy, between the discrete average CWHS and SSTA time series were computed as:

where \( - \infty < n < \infty , \) the asterisk represents complex conjugation, and E is the expected value operator [29, 30], as implemented in MATLAB®’s Signal Processing Toolbox. In our cross-correlation of the species-species, average CWHS time series and SSTA time series over the 2012–2018 study period, Rxy values closer to 1 would therefore indicate that coral color coral bleaching of a given coral taxa resulted likely from increased thermal stress according to the SSTA record. Alternately, lower Rxy values closer to 0 would indicate coral insensitivity to thermal stress and changes in sea water temperature.

Finally, in order to investigate the potential correlation between coral growth habit (boulder vs. plate-type) and thermal stress, a dendrogram analysis (hierarchical binary cluster tree) was performed in MATLAB® for the dominant seven coral species, in which the species-specific CWHS time series were included in the analysis.

3 Results

NOAA SSTAs averaged over the two TCI 5 km (0.05o) grid cells, from 1985 to present show a clear increasing (warming) trend (Fig. 3). The 1997–1998, 2009–2010, and 2014–2017 mass Global Bleaching Events (GBEs) are indicated. The 2012–2018 study interval was used to analyze TCI sensitivity to the 2014–2017 GBE (Fig. 3). Maximum SSTA and DHW across the entire Caribbean region in late 2015 during the 2014–2017 GBE is shown in Fig. 4. While the TCI site is located in the NE Caribbean and generally cooler with its closer proximity to Atlantic currents, maximum 2015 SSTA and DHW for the study site were comparable with the Caribbean regions experiencing higher thermal stress, but not at the extremes found in other regions in 2015 (Fig. 4).

NOAA Sea Surface Temperature Anomalies (SSTAs), averaged over the three Turks and Caicos Islands 5 km grid cells, 1985 to present. The 1997–1998, 2009–2010, and 2014–2017 mass Global Bleaching Events (GBEs) are bracketed in gray. The 2012–2018 study interval, used in this paper to analyze TCI sensitivity to the 2014–2017 GBE, is bracketed by the black bar at the top-right of the figure

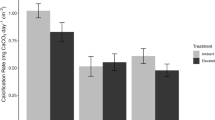

Interannual variability in CoralWatch Coral Health Chart color for a boulder type and b plate type corals all survey sites between 2012 and 2018. Average lighter colors (1–2) indicate stressed corals whereas average darker coral colors (4+) indicate healthier, less stressed coral habitats. NOAA Degree Heating Week (DHW) depicted in (c)

The dominant coral taxa in South Caicos Island include: plate-type Agaricia spp. (29%), boulder-type Porites astreoides (16%), and boulder-type Siderastrea spp. (12%), as seen in Table 1. A time series for boulder and plate-type corals represents the average boulder or plate-type coral CWHS values for each survey (Fig. 5). The NOAA Degree Heating Week (DHW) in Fig. 5c illustrates the interannual variability in SST over the study period, averaged over the NOAA-1 and NOAA-2 5 km grid cells (Fig. 2). An ANOVA analyses of annual DHW trends reveals that 2013, 2015, and 2016 were significantly warmer than 2012, 2014, and 2017–2018 (p < 0.05) due to abnormally high SSTA in these years compared with the remainder of the years included in the analysis.

The CWHS time series visually depicts an apparent coupling between coral color (coral health) and thermal stress, as the average CWHS time series declines in magnitude during the GBE event (Fig. 5). Although boulder and plate coral types generally drop in value, indicating bleaching during the GBE, data indicate a general recovery in CWHS values after the GBE to pre-GBE (April 2014-April 2015) CWHS averages within 1 year following the end of the GBE (Fig. 5).

While the CWHS trends appear to suggest a coral bleaching stress response to, and recovery from the late 2015 DHW peak thermal stress associated with the GBE, one-way ANOVA analyses of the fitted CWHS distributions (Fig. 6) for boulder and plate-type corals provides more meaningful insight into the bleaching response. In our analysis, only plate-type corals exhibited significant color reduction during the 2014–2017 GBE, indicated by a statistically significant (p < 0.05) shift in color distributions. Average CWHS trends for both types increased after the GBE, with boulder-type corals darkening significantly (higher average CWHS, p < 0.05) more than pre-GBE color distributions in the post-GBE recovery (2017 +) time window (Table 2).

Results from our cross-correlation analyses (Eq. 1) of species-specific CWHS and SSTA signals (Fig. 7) reveal strong coupling between coral color and SSTA for the dominant coral taxa sampled between 2012 and 2018 during the 104 surveys. As seen in Fig. 7, even though boulder corals are most strongly correlated with changes in SSTA, the correlation appears to be dominated by post-GBE coupling, given boulder-type corals did not significantly bleach during the GBE. Cross-correlation analyses over each of the 3 analysis periods (pre-GBE, GBE, and post-GBE) could help devolve which coral color signals were most correlated with SSTA over each of these intervals versus the entire study period. The dominating coral species in the TCI appear to be the most influenced by rising SSTA. Similarly, the Rxy values for corals not sampled frequently (e.g., < ~ 5% of overall dataset) may not yield as much insight into species-specific coupling of coral-color to water temperature variability.

Cross-correlation of Turks and Caicos coral taxa with SSTA, showing coral species most sensitive to thermal stress and exhibiting bleaching in response to the 2014–2017 Global Bleaching Event. Sample sizes for each species can be found on Table 1

The dendrogram analysis (Fig. 8) reveal that coral color and pigmentation variability for the principal coral taxa surveyed offshore of South Caicos during the 2012–2018 study period is independent of coral growth habit. As shown on Fig. 8, color variability of plate-type Agaricia sp. is most correlated with boulder-types Porites astreoides (Rxy = 0.82) and Siderastrea sp. (Rxy = 0.65). The CWHS signals for boulder-types corals Meandrina meandrites and Siderastrea sp. were found to be strongly coupled (Rxy = 0.7). In summary, the dendrogram analysis of CWHS signals adds to our understanding of coral response to thermal stress by revealing that coral response to thermal stress in the TCI region is independent of coral growth habit.

Dendrogram of interspecific color and pigmentation variability for principal coral taxa surveyed offshore of South Caicos during the 2012–2018 study period using cross-correlation analysis of average CWHS signals. As seen, coral color coupling to thermal stress is not dependent upon coral growth habit, as the dendrogram analysis reveals close correlation between coral species of differing growth habits

4 Discussion

Our study revealed that significant coral bleaching and restoration of coral color occurred offshore of South Caicos Island during, and after the 2014–2017 GBE for plate-type corals. Instead of a linear decline in average coral color over the 2012–2018 time window, principal coral taxa in our analysis exhibited strong coupling with longer wavelength regional sea surface temperature (SST) signals. We recognize a multitude of factors influence the susceptibility of a coral to bleach or its ability to recover. Such influences are the coral community composition, geography, endosymbiont type, and multiple temperature metrics [31].

However, while our study found temperature to play a direct role in coral color decline, many studies have found Symbiodinium to have a large impact on coral recovery from increased ocean temperatures [7, 17]. Interestingly, plate-type corals contain a different type of Symbiodinium that is not as resilient to thermal stress which may explain why plate-type corals experienced significant bleaching in response to the anomalously high SSTAs in 2015 and 2016 (Figs. 5, 6) [32, 33]. Whereas boulder-type corals did not significantly respond to the GBE, many studies have found P. astreoids and Siderastrea spp., two dominant boulder-type corals in our study, to have resilient Symbiodinium clades (Clades A4a, B1, C3) that have made them resilient to intense bleaching events [32, 34, 35].

Nonetheless, while Symbiodinium clades may explain the resilience and recovery differences across plate and boulder-type corals, the three South Caicos reef-dominating corals, Agaricia spp., P. astreoids and Siderastrea spp., all share opportunistic life history traits that allow them to monopolize and persist in degraded reef habitats [34, 36,37,38]. Overall, supporting research seems to conclude that Symbiodinium types and life history traits are important determinants in the survival of corals in degrading reef habitat with multiple environmental stressors [34,35,36, 39].

While our study only found plate-type corals to bleach significantly, both plate-type and boulder-type significantly rebounded to pre-GBE health by the beginning of 2017 with boulder-type corals darkening even more post-GBE (Figs. 5, 6). However, looking outside the physiological processes impacting recovery, environmental factors influence the recovery process. For example, Fig. 3 shows a large decrease in SSTA in 2017 due to the two hurricanes, Irma and Maria that passed through the Caribbean and reduced SST, inducing local upwelling and a reduction in light stress. Furthermore, as indicated by the dendrogram analysis (Fig. 8), coral color response to thermal stress is independent of coral growth habit.

Our cross-correlation analysis of CWHS with thermal stress indicated that, not only was the bleaching of plate type corals during the GBE directly attributable to increases in water temperature, but that cooler, post-GBE regional water temperatures resulted in coral health recovery for both boulder and plate-type corals, albeit with less coral color variability post-GBE than pre-GBE. The cross-correlation analysis of coral color and SSTA variability (Fig. 7) suggested which coral species and taxa are most susceptible to bleaching and stress during GBEs. Furthermore, corals most strongly correlated with SSTA variability may be the most likely to experience widespread mortality in the Caribbean with more frequent, more extreme GBEs associated with climate change. It is important to note, however, that coral vulnerability to bleaching may be due to different stressors, including multiple temperature metrics. Specifically, McClanahan et al. [31] find that, “Corals experience temperatures that differ from those measured by satellites, and their responses also integrate acclimation, adaptation and histories of stress,” and exercise caution when interpreting products like DHW due to the spatial complexities and need for additional ground truthing of satellite-derived products to properly represent the thermal history at any given site. Pernice and Hughes [40] highlight the need for proper representation of thermal history, as fluctuations of extreme temperatures may improve certain coral species’ ability to withstand thermal stress, as found by Oliver and Palumbi [41].

Our results support Muñiz-Castillo et al. ’s [42] finding that the TCI belong in the Caribbean ecoregion least exposed to heat stress and with the greatest percentage of its area without bleaching and mortality risk. Whereas our results reveal coral color darkening, i.e., statistically-significant shift of mean color distribution from lighter to darker hues, in response to thermal stress offshore of South Caicos Island, the relatively low thermal stress experienced in this region compared with other Caribbean regions more stressed during the 2014–2017 GBE (i.e., Central and eastern Venezuelan, Honduran and Nicaraguan Miskito Cays and nearby islands, etc., [42]), adds important regional context.

While coral bleaching in the Caribbean has been documented since the 1980s [43, 44], the increase in frequency and intensity of GBEs with climate change has added unprecedented stress on coral habitats regionally and globally. Recent studies assess the rapid decline in scleractinian corals and the transformation of dominant reef-building corals to reefs covered in macroalgae [43,44,45]. An ecological study by Dikou et al. [46] revealed that South Caicos benthic substrate was dominated by turf algae and dead coral rubble with live coral cover only encompassing approximately 2–7% of benthic space. Of the live coral found in the benthic space the dominating species were Agaricia spp., Montastraea spp., and Siderastrea spp. [46]. Thus, in general, the greater Caribbean reefs are shifting, as a result, from historically large, slow-growing scleractinian colonies of Acropora and Montastraea to smaller colonies of ‘weedy’ species, such as P. astreoides [45, 47, 48].

5 Conclusion

In summary, assessing coral health using the CoralWatch health chart methodology as described by Siebeck et al. [20] has proven to be an efficient diagnostic tool in diagnosing coral reef bleaching and recovery in response to regional thermal stress. Results from this study suggest a change in the composition of modern reefs, moving from massive colonies of scleractinian corals to ‘weedy’ scleractinian corals. Future studies in this region should examine the resilient endosymbiont types and life history traits of corals that have assisted in the survival of dominant reef species, representing a key factor for the emerging assisted evolution science as outlined by van Oppen et al. [49]. Further investigations of Turks and Caicos coral habitats are imperative to help understand specific coral response mechanisms and therefore predict how Caribbean region coral reefs may respond to more frequent, and more intense GBEs in the coming decades. This research is important not only to understand the mechanisms behind survival in high stress environments but in order to prioritize conservation efforts, such as establishing effective Marine Protected Areas.

References

Hoegh-Guldberg O (1999) Climate change, coral bleaching and the future of the world’s coral reefs. Mar Freshw Res 50(8):839–866. https://doi.org/10.1071/MF99078

Eakin CM, Heron SF, Caldwell MM, Heldmaier G, Jackson RB, Lough JM, Van Oppen MJH (2009) Climate variability and change: monitoring data and evidence for increased coral bleaching stress, vol 205

Kwiatkowski L, Cox P, Halloran PR, Mumby PJ, Wiltshire AJ (2015) Coral bleaching under unconventional scenarios of climate warming and ocean acidification, vol 5. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2655

Ainsworth TD, Heron SF, Ortiz JC, Mumby PJ, Grech A, Ogawa D, Eakin CM, Leggat W (2016) Climate change disables coral bleaching protection on the Great Barrier Reef. Science 352(6283):338–342. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac7125

Hughes TP, Kerry JT, Baird AH, Connolly SR, Dietzel A, Hoey AS, Hoogenboom MO, McWilliam MJ, Pratchett MS, Torda G, Eakin CM, Heron SF, Liu G, Skirving WJ, Pears RJ, Stella JS (2018) Global warming transforms coral reef assemblages. Nature 556(7702):492–496. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0041-2

Skirving WJ, Heron SF, Marsh BL, Liu G, De La Cour JL, Geiger EF, Eakin CMJCR (2019) The relentless march of mass coral bleaching: a global perspective of changing heat stress. Coral Reefs 38(4):547–557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-019-01799-4

Berkelmans R, van Oppen MJH (2006) The role of zooxanthellae in the thermal tolerance of corals: a ‘nugget of hope’ for coral reefs in an era of climate change. Proc R Soc Biol Sci 273(1599):2305–2312

Nyström M, Folke C, Moberg F (2000) Coral reef disturbance and resilience in a human-dominated environment. Trends Ecol Evol (Regular ed Print) 15(10):413–417

Frieler K, Meinshausen M, Golly A, Mengel M, Lebek K, Donner SD, Hoegh-Guldberg OK (2013) Limiting global warming to 2 °C is unlikely to save most coral reefs. Nat Clim Change 3(2):165–170

Pachauri RK, Allen MR, Barros VR, Broome J, Cramer W, Christ R, Church JA, Clarke L, Dahe Q, Dasgupta P, Dubash NK, Edenhofer O, Elgizouli I, Field CB, Forster P, Friedlingstein P, Fuglestvedt J, Gomez-Echeverri L, Hallegatte S, Hegerl G, Howden M, Jiang K, Jimenez Cisneroz B, Kattsov V, Lee H, Mach KJ, Marotzke J, Mastrandrea MD, Meyer L, Minx J, Mulugetta Y, O’Brien K, Oppenheimer M, Pereira JJ, Pichs-Madruga R, Plattner G-K, Pörtner H-O, Power SB, Preston B, Ravindranath NH, Reisinger A, Riahi K, Rusticucci M, Scholes R, Seyboth K, Sokona Y, Stavins R, Stocker TF, Tschakert P, van Vuuren D, van Ypserle J-P (2014) Climate change 2014: synthesis report. Contribution of working groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC, Geneva

Van H, van Hooidonk R, Maynard J, Liu Y, Lee S-K (2015) Downscaled projections of Caribbean coral bleaching that can inform conservation planning. Glob Change Biol 21(9):3389–3401

Gardner T, Côté I, Gill J, Grant A, Watkinson AR (2005) Hurricanes and Caribbean coral reefs: impacts, recovery patterns, and role on long-term decline. Ecology 86(1):174–184

Status of coral reefs of the World (2004) Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville

Lough JM, Anderson KD, Hughes TP (2018) Increasing thermal stress for tropical coral reefs: 1871–2017. Sci Rep 8(1):6079. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-24530-9

Hughes T, Kerry J, Álvarez Noriega M, Álvarez Romero J, Anderson K, Baird A, Babcock R, Beger M, Bellwood D, Berkelmans R, Bridge T, Butler I, Byrne M, Cantin N, Comeau S, Connolly S, Cumming G, Dalton S, Diaz Pulido G, Eakin CM, Figueira W, Gilmour J, Harrison H, Heron S, Hoey A, Hobbs J-P, Hoogenboom M, Kennedy E, Kuo C-y, Lough J, Lowe R, Liu G, McCulloch M, Malcolm H, McWilliam M, Pandolfi J, Pears R, Pratchett M, Schoepf V, Simpson T, Skirving W, Sommer B, Torda G, Wachenfeld D, Willis B, Wilson SK (2017) Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature 543(7645):373–377

Thornhill D, Rotjan R, Todd B, Chilcoat G, Iglesias Prieto R, Kemp D, LaJeunesse T, Reynolds J, Schmidt G, Shannon T, Warner M, Fitt W, Voolstra CR (2011) A connection between colony biomass and death in Caribbean reef-building corals. PLoS ONE 6(12):e29535

Sampayo EM, Ridgway T, Bongaerts P, Hoegh Guldberg O (2008) Bleaching susceptibility and mortality of corals are determined by fine-scale differences in symbiont type. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105(30):10444–10449

Marshall NJ, Kleine D, Dean AJ (2012) CoralWatch: education, monitoring, and sustainability through citizen science. Front Ecol Environ 10(6):332–334

Fabricius K, Langdon C, Uthicke S, Humphrey C, Noonan S, Death G, Okazaki R, Muehllehner N, Glas M, Lough JM (2011) Losers and winners in coral reefs acclimatized to elevated carbon dioxide concentrations. Nat Clim Change 1(3):165–169

Siebeck UE, Marshall NJ, Klüter A, Hoegh-Guldberg O (2006) Monitoring coral bleaching using a colour reference card. Coral Reefs 25(3):453–460

Status of coral reefs of the World (2000) Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville

Jackson JBC, Donovan MK, Cramer KL, Lam VV (2014) Status and trends of Caribbean coral reefs: 1970–2012. Gland, Switzerland

Strong AE, Barrientos CS, Duda C, Sapper J (1997) Improved satellite techniques for monitoring coral reef bleaching. In: 8th International Coral Reef Symposium, pp 1495–1498

Liu G, Strong A, Skirving W (2003) Remote sensing of sea surface temperatures during 2002 Barrier Reef coral bleaching. EOS Trans Am Geophys Union 84(15):137–141

Skirving W, Strong AE, Liu G, Arzayus F, Liu C, Sapper J (2006) Extreme events and perturbations of coastal ecosystems: sea surface temperature change and coral bleaching. Remote sensing and digital image processing, vol 9. Springer, Berlin

Johnson NL, Kotz S, Balakrishnan N (1993) Continuous univariate distributions, vol 1. Wiley-Interscience, Hoboken

Johnson NL, Kotz S, Balakrishnan N (1994) Continuous univariate distributions, vol 2. Wiley-Interscience, Hoboken

Bowman AW, Azzalini A (1997) Applied smoothing techniques for data analysis. Oxford University Press, New York

Buck J, Daniel MM, Singer AC (2002) Computer explorations in signals and systems using MATLAB®, 2nd edn. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River

Stoica P, Moses R (2005) Spectral analysis of signals. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River

McClanahan TR, Darling ES, Maina JM, Muthiga NA, D’agata SD, Jupiter SD, Arthur R, Wilson SK, Mangubhai S, Nand Y, Ussi AM, Humphries AT, Patankar VJ, Guillaume MMM, Keith SA, Shedrawi G, Julius P, Grimsditch G, Ndagala J, Leblond J (2019) Temperature patterns and mechanisms influencing coral bleaching during the 2016 El Niño. Nat Clim Change 9(11):845–851. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0576-8

LaJeunesse TJMB (2002) Diversity and community structure of symbiotic dinoflagellates from Caribbean coral reefs. Mar Biol 141(2):387–400

Venn A, Wilson M, Trapido-Rosenthal H, Keely B, Douglas A (2006) The impact of coral bleaching on the pigment profile of the symbiotic alga, Symbiodinium. Plant, Cell Environ 29:2133–2142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.01587.x

Green DH, Edmunds PJ, Carpenter RC (2008) Increasing relative abundance of Porites astreoides on Caribbean reefs mediated by an overall decline in coral cover. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 359:1–10

Thornhill D, LaJeunesse T, Kemp D, Fitt W, Schmidt GW (2006) Multi-year, seasonal genotypic surveys of coral-algal symbioses reveal prevalent stability or post-bleaching reversion. Mar Biol 148(4):711–722

Oxenford HA, Nurse L, Goodridge R, Baldwin K, Finney C, Roach R, Brathwaite A, Hinds F (2008) Quantitative observations of a major coral bleaching event in Barbados, Southeastern Caribbean. Clim Change 87(3–4):435–449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-007-9311-y

Aronson R, Macintyre I, Wapnick C, O’Neill MW (2004) Phase shifts, alternative states, and the unprecedented convergence of two reef systems. Ecology 85(7):1876–1891

Smith SR (1992) Patterns of coral recruitment and post-settlement mortality on Bermuda’s reefs: comparisons to Caribbean and Pacific reefs. Am Zool 32(6):663–673

Rowan R, Knowlton N, Baker A, Jara J (1997) Landscape ecology of algal symbionts creates variation in episodes of coral bleaching. Nature 388(6639):265–269

Pernice M, Hughes DJ (2019) Forecasting global coral bleaching. Nat Clim Change 9(11):803–804. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0593-7

Oliver TA, Palumbi SR (2011) Do fluctuating temperature environments elevate coral thermal tolerance? Coral Reefs 30:429–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-011-0721-y

Muñiz-Castillo A, Rivera-Sosa A, Chollett I, Eakin CM, Andrade-Gómez L, McField M, Arias-González JE (2019) Three decades of heat stress exposure in Caribbean coral reefs: a new regional delineation to enhance conservation. Sci Rep 9(1):11013

Gardner TA, Côté IM, Gill JA, Grant A, Watkinson AR (2003) Long-term region-wide declines in Caribbean corals. Science (New York, NY) 301(5635):958–960

Jackson J (1997) Reefs since Columbus. Coral Reefs 16(1):S23–S32

Knowlton N (2001) The future of coral reefs. Proc Natl Acad Sci 98(10):5419–5425. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.091092998

Dikou A, Ackerman C, Banks C, Dempsey A, Fox M, Gins M, Hester P, Parnes A, Roach S, Rohde J, Spital C, Tapleshay M, Thomas L (2009) Ecological assessment to detect imminent change in coral reefs of Admiral Cockburn Land and Sea National Park, Turks and Caicos Islands. Mar Ecol 30(4):425–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0485.2009.00291.x

Adjeroud M, Michonneau F, Penin L, Vidal-Dupiol J, Salvat B, Galzin R, Chancerelle Y, de Loma TL, Edmunds PJ, Thibaut L (2009) Recurrent disturbances, recovery trajectories, and resilience of coral assemblages on a South Central Pacific reef. Coral Reefs 28(3):775–780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-009-0515-7

Edmunds PJ (2010) Population biology of Porites astreoides and Diploria strigosa on a shallow Caribbean reef. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 418:87–104

van Oppen MJH, Oliver JK, Putnam HM, Gates RD (2015) Building coral reef resilience through assisted evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci 112(8):2307–2313. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1422301112

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank The School for Field Studies (SFS) providing historic data for this analysis. Thank you, Erick Geiger, NOAA Coral Reef Watch Scientist, for providing the extracted NOAA data products for the study site. The authors also would like to thank the following individuals who performed the reef surveys: Chrissy Lamendola, Holden Harris, Billie Beckley, Sophia Wasserman, Adrian Jourdan, Erin Garnett, Adrian Jourdan, Hannah Reich, Brent Sacks, Valerie Cleland, Anna Campbell, Anela Akiona, Travis Gomez, Emily Stokes, Connor Burke, Jess Bechhofer, Emily Volkman, Lily Zhao, Sarah Fleming, Taylor Determan, Noelle Helder, Rachel Baker, Mariana Silva, and Eva Lenain. The authors thank A. Cohen and B. Fouke for helpful comments, which improved the manuscript. J. C. Pettijohn is supported by a University of Illinois Office of the Provost Initiative on Teaching Advancement (PITA) Grant and College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, Applied Technologies for Learning in the Arts and Sciences (ATLAS) Grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Knipp, A.L., Pettijohn, J.C., Jadot, C. et al. Contrasting color loss and restoration in survivors of the 2014–2017 coral bleaching event in the Turks and Caicos Islands. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 331 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-020-2132-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-020-2132-6