Abstract

We consider the MRI physics in a low-field MRI scanner, in which permanent magnets are used to generate a magnetic field in the millitesla range. A model describing the relationship between measured signal and image is derived, resulting in an ill-posed inverse problem. In order to solve it, a regularization penalty is added to the least-squares minimization problem. We generalize the conjugate gradient minimal error (CGME) algorithm to the weighted and regularized least-squares problem. Analysis of the convergence of generalized CGME (GCGME) and the classical generalized conjugate gradient least squares (GCGLS) shows that GCGME can be expected to converge faster for ill-conditioned regularization matrices. The \({\ell}_{p}\)-regularized problem is solved using iterative reweighted least squares for \(p=1\) and \(p=\frac{1}{2}\), with both cases leading to an increasingly ill-conditioned regularization matrix. Numerical results show that GCGME needs a significantly lower number of iterations to converge than GCGLS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In low-field magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), magnetic field strengths in the millitesla (mT) range are used to visualize the internal structure of the human body. In traditional MRI scanners, magnetic field strengths of several tesla are the norm. While these high-field MRI scanners yield images of excellent quality, their cost, size and infrastructure demands make them unattainable for developing countries. Therefore, the design of low-field MRI scanners is of great clinical relevance. This research is part of a project that aims toward creating an inexpensive low-field MRI scanner using a Halbach cylinder that can be used for medical purposes. A Halbach cylinder is a configuration of permanent magnets that generates a magnetic field inside the cylinder and a very weak, or in the ideal case, no magnetic field outside of it. Imaging can be done by making use of the variations in the magnetic field. However, the resulting reconstruction problem is very ill-posed. This is due to the nonlinearity of the magnetic field inside the Halbach cylinder that we consider. This field leads to non-bijective mappings and potentially gives rise to aliasing artifacts in the solution. Additionally, in the center of the cylinder, there is very little variation in the field, limiting the spatial resolution in that area. Another complication we face is low signal-to-noise ratios. Nevertheless, in a similar project, Cooley et al. [6] have shown that it is possible to reconstruct magnetic resonance images given signals obtained with a device based on a Halbach cylinder, using a simplified signal model in which similar assumptions are made as in high-field MRI. In this paper, we revisit the underlying physics and formulate the general signal model for MRI without making these assumptions.

Regularization is required to limit the influence of noise on the solution of the image reconstruction problem as much as possible. In this paper, we reformulate the weighted and regularized least-squares problem such that the conjugate gradient minimal error (CGME) method (see for example [2]) can be used to solve it for nontrivial covariance and regularization matrices, filling a gap in existing literature as far as we know. We do this by deriving the Schur complement equation for the residual. A similar approach is taken by Orban and Arioli [25] to derive generalizations of the Golub–Kahan algorithm. Using these algorithms, they formulate generalizations of LSQR, Craig’s method and LSMR (see [2]) for the general regularization problem. We explain in which cases generalized CGME (GCGME) may have an advantage over generalized conjugate gradient least squares (GCGLS). Additionally, we apply GCGME to MRI data with different types of regularization.

The present paper results from our efforts to address the challenges of low-field MRI using advanced image processing. It is interdisciplinary in nature, with an emphasis on image reconstruction techniques. The contributions of this paper include a signal model for low-field MRI that does not rely on any field assumptions as encountered in high-field MRI. Also, a new generalization of the conjugate gradient method is presented for the weighted and regularized least-squares problem, including an analysis of when this generalization is expected to perform best. Although we focus on a low-field MRI setting, this algorithm is generally applicable to \({\ell}_{p}\)-regularized least-squares problems.

1.1 Low-field MRI

In magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the internal structure of the body is made visible by measuring a voltage signal that is induced by time variations of the transverse magnetization within a body part of interest. Based on this measured signal, an image of the spin density \(\rho\) of different tissue types may be obtained.

To be specific, first the body part of interest is placed in a static magnetic field \(\vec {B}=B_0(\vec {r})\vec {i}_x\) that is oriented in the x-direction in our Halbach measurement setup (see Fig. 1a) with a position-dependent x-component \(B_0=B_0(\vec {r})\). A net magnetization

will be induced that is oriented in the same direction as the static magnetic field. In the above expression, \(\gamma = 267 \times 10^{6}~{\text {rad}}~{\text {s}}^{-1}~{\text {T}}^{-1}\) is the proton gyromagnetic ratio, \(\hbar = 1.055 \times 10^{-34}~{\text {m}}^2~{\text {kg}}~{\text {s}}^{-1}\) is Planck’s constant divided by \(2\pi\), \(k_{\text {B}} = 1.381 \times 10^{-23}~{\text {m}}^2~{\text {kg}}~{\text {s}}^{-2}~{\text {K}}^{-1}\) is Boltzmann’s constant, and T is the temperature in kelvin.

Subsequently, a radiofrequency pulse is emitted to tip the magnetization toward the transverse yz-plane. After this pulse has been switched off (in our model at \(t=0\)), the magnetization rotates about the static magnetic field with a precessional frequency \(\omega\) (also known as the Larmor frequency) given by

and will relax back to its equilibrium given by Eq. (1). During this process, an electromagnetic field is generated that can be locally measured outside the body using a receiver coil. This measured signal is amplified, demodulated, and low-pass filtered, and for the resulting signal, we have the signal model [23]:

where \({\mathbb {D}}\) is the domain occupied by the body part of interest, \(T_2(\vec {r})\) is the transverse relaxation time, \(c(\vec {r})\) is the so-called coil sensitivity with amplification included, \(M_{\perp }(\vec {r},0)\) is the transverse magnetization at \(t=0\), and \(\varDelta \omega\) is the difference between the Larmor frequency and the demodulation frequency that is used. For this demodulation frequency, we take the frequency that corresponds to the static magnetic field at the center of our imaging domain.

Furthermore, using Eq. (2) in the expression for \(M_0\), we have

and since the initial transverse magnetization \(M_{\perp }(\vec {r},0)\) is proportional to \(M_0(\vec {r})\), we can also write our signal model as:

where it is understood that all remaining proportionality constants have been incorporated in the coil sensitivity \(c(\vec {r})\). Conventionally, the spatial dependence of \(\omega\) is ignored. Therefore, the \(\omega ^2\) term usually does not appear in MRI literature. However, we incorporate it into our model because of the relatively large inhomogeneities in the magnetic field we are considering. We remark that Eq. (5) is a general MRI signal model, but it is more suitable for low-field MRI because the assumptions made for high-field MRI (namely, a very strong and homogeneous magnetic field) do not hold for low field. Ignoring \(T_2\) relaxation, the final signal model becomes

The measurements taken in an MRI scanner consist of noisy samples of the signal given by Eq. (6):

where \(b_i\) denotes the ith sample of the signal, measured at time \(t_i\). L is the number of time samples, and \(e_i\) is the measurement error.

1.1.1 Model-based image reconstruction

In high-field MRI, the magnetic field is manipulated in such a way that Eq. (6) constitutes a Fourier transform. The resulting linear problem is well posed, and the image can be efficiently obtained using an inverse FFT. However, in low-field MRI, the magnetic field is usually strongly inhomogeneous, which prevents us from using standard FFT routines. Model-based image reconstruction can be applied instead [10].

In order to estimate \(\rho ({\mathbf {r}})\), we write it as a finite series expansion of the form:

where \(\phi (\cdot )\) denotes the object basis function, \({\mathbf {r}}_j\) is the center of the jth basis function and \(x_j\) are the coefficients. Usually, rectangular basis functions are used, in which case N is the number of pixels. Combining Eqs. (6) and (8) yields

where

When the basis functions are highly localized, a “center of pixel” approximation can be used:

Here, \(\varDelta x \varDelta y\) is the pixel size and \(\varDelta z\) is the thickness of the slice that is being imaged. Combining Eqs. (7) and (8) yields one system of equations:

where the elements of \({\mathbf {A}}\) are described by Eq. (11). This problem is ill-posed due to the nature of the magnetic field that is present within the Halbach cylinder. As shown in Fig. 2, the field has a high degree of symmetry. The precessional frequency depends linearly on the magnitude of the field, which means that several pixels will correspond to the same frequency. Therefore, using only one measured signal, it is impossible to determine the contribution of each pixel to the signal. By rotating the object to be imaged and hence obtaining a multitude of different signals corresponding to different rotations of the same object, we plan to mitigate this problem. The same approach was taken by Cooley et al. [6] (Table 1).

2 Methodology

The model that is used to reconstruct \(\rho\) is given by the linear system of Eq. (12). We can attempt to solve for \({\mathbf {x}}\) by finding a solution to the least-squares problem

This can be done by applying the conjugate gradient method introduced by Hestenes and Stiefel in 1952 [19] to the normal equations

with \({\mathbf {A}}^{\mathrm{H}}\) denoting the Hermitian transpose of \({\mathbf {A}}\).

The conjugate gradient method tailored to Eq. (14) was proposed in [19] and is usually referred to as conjugate gradient for least squares (CGLS). The difference with the standard conjugate gradient method lies in the increased stability of the CGLS method. A review of the literature reveals that this method is known by other names as well. In [29], Saad calls it conjugate gradient normal residual (CGNR), while Hanke [14] and Engl [9] use the term conjugate gradient for the normal equations (CGNE).

On the other hand, the second normal equations

can be solved using the conjugate gradient method as well. In the literature, this is usually called conjugate gradient minimal error (CGME). However, in [1] it is called conjugate gradient normal error (CGNE), while [30] uses the term Craig’s method. It was introduced by Craig in 1955 [7]. CGLS and CGME are discussed by Björck in [2], Hanke in [14] and Saad in [29]. While CGLS minimizes the residual \({\mathbf {r}}= {\mathbf {b}}-{\mathbf {A}}{\mathbf {x}}\) in the \(\ell _2\) norm over the Krylov subspace \({\mathbf {x}}_0 + {\mathcal {K}}_k({\mathbf {A}}^{\mathrm{H}}{\mathbf {A}},{\mathbf {A}}^{\mathrm{H}}{\mathbf {b}}-{\mathbf {A}}^{\mathrm{H}}{\mathbf {A}}{\mathbf {x}}_0)\), CGME minimizes the error (over the same subspace). The main drawback of this latter method is that, in theory, it only works for consistent problems for which \({\mathbf {b}}\in {{{\mathbf {R}}}({\mathbf {A}})}\). This means that the method is of limited use for most problems in practice, because the presence of noise renders the system inconsistent. In [21], this problem is circumvented by defining an operator \({\mathbf {Q}}\) that projects \({\mathbf {b}}\) onto the column space of \({\mathbf {A}}\). Subsequently, \({\mathbf {A}}{\mathbf {x}}= {\mathbf {Q}}{\mathbf {b}}\) can be solved using CGME. The obvious disadvantage of this method is that \({\mathbf {Q}}{\mathbf {b}}\) has to be calculated and stored.

2.1 Regularization of the problem

Regularization of an ill-posed problem aims to make the problem less sensitive to noise by taking into account additional information, i.e., it aims at turning an ill-posed problem into a well-posed one. Like many iterative methods, both CGLS and CGME have a regularizing effect if the iterating procedure is stopped early: keeping the number of iterations low keeps the noise from corrupting the result too much. If a large number of iterations is used, noise can have a very strong effect on the solution. The regularizing properties of CGLS were established by Nemirovskii in [24] and are discussed in [2, 9, 14], among others. CGME’s regularizing effect was shown by Hanke in [15]. However, we are interested in what Hansen [17] calls general-form Tikhonov regularization, i.e., adding a regularization term to minimization problem (13), leading to

where \({\mathbf {W}}\)is a weighting matrix, and \({\mathbf {R}}\) is a Hermitian positive definite matrix. Using a CG algorithm to solve Eq. (16) is a natural choice [10]. The CG method is often used to solve image reconstruction problems in MRI when a conventional Fourier model is insufficient (see for example [11, 27, 34]). Additionally, it is used as a building block for other algorithms used in MRI by Pruessman [26], Ramani and Fessler [28] and Ye et al. [38], among others. It is straightforward to generalize CGLS to regularized and weighted least-squares problems of the form of Eq. (16). In this case, because of the well-posedness of the resulting minimization problem, the noise does not influence the solution as much as when Eq. (13) is considered and increasing the number of iterations does not lead to a noisier solution. In this paper, we will use \({\mathbf {W}}= {\mathbf {C}}^{-1}\), where \({\mathbf {C}}\) is the covariance matrix of the noise:

For our application, the noise can be considered to be white, which means that \({\mathbf {C}}= {\mathbf {I}}\). However, for completeness, we consider the general case. In case \({\mathbf {R}}={\mathbf {I}}\), Eq. (17) reduces to a minimization problem with standard Tikhonov regularization [36]. The optimal value of the regularization parameter \(\tau\) is usually unknown. An approach that is often used to find a suitable value is the L-curve method [16]. By taking the gradient and setting it equal to \({\mathbf {0}}\), the normal equations are obtained:

Again, the conjugate gradient method can be used to solve Eq. (18). We will use the term GCGLS (generalized CGLS) to refer to the conjugate gradient method applied to the normal Eq. (18).

Saunders [30] extended Craig’s method, which is mathematically equivalent to CGME, to the regularized least-squares problem with \({\mathbf {C}}={\mathbf {I}}\) and \({\mathbf {R}}={\mathbf {I}}\). He introduces an additional variable \({\mathbf {s}}\) and considers the constrained minimization problem

By defining \(\tilde{{\mathbf {r}}} = \sqrt{\tau } {\mathbf {s}}= {\mathbf {b}}-{\mathbf {A}}{\mathbf {x}}\), he shows that this constrained minimization problem is equivalent to

For every \(\tau >0\), \(\begin{pmatrix} {\mathbf {A}}&\sqrt{\tau }{\mathbf {I}}\end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix}{\mathbf {x}}\\ {\mathbf {s}}\end{pmatrix} = {\mathbf {b}}\) is consistent, and hence, Eq. (19) can be solved using CGME. Unfortunately, no advantages to using CGME were found. Note that such a reformulization is necessary because the standard way of including the regularization matrix \({\mathbf {R}}={\mathbf {I}}\), by simply solving the so-called damped least-squares problem

using CGME, is not possible, due to the inconsistency of the system. Reformulation of CGME for general-form regularization can be achieved using a Schur complement approach as will be shown as follows.

Again, we consider Eq. (17). We introduce the variable \({\mathbf {r}}= {\mathbf {C}}^{-1}({\mathbf {b}}-{\mathbf {A}}{\mathbf {x}}),\) and we note that \(||{\mathbf {A}}{\mathbf {x}}-{\mathbf {b}}||^2_{{\mathbf {C}}^{-1}}=||{\mathbf {r}}||^2_{\mathbf {C}}\). Then, minimization problem (17) can be formulated as a constrained minimization problem:

and using the technique of Lagrange multipliers, we find that

If we eliminate \({\mathbf {r}}\) from Eq. (23), the original normal Eq. (18) is obtained, whereas if we assume \(\tau {\mathbf {R}}\) is invertible and we subsequently eliminate \({\mathbf {x}}\), we end up with a different set of equations. As mentioned before, the first option leads to the GCGLS method. The latter approach leads to the GCGME method.

2.2 GCGLS

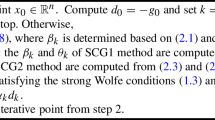

By applying the conjugate gradient method to Eq. (18) and making some adjustments to increase stability (see [2] for details), the GCGLS algorithm is obtained:

Here, M is the total number of data points measured and N is the number of pixels in the image. The residual of the normal Eq. (18) is denoted by \({\mathbf {s}}_k\). We remark that the vectors on the left side can be overwritten by the vectors on the right. Only eight vectors have to be stored, namely \({\mathbf {x}}\), \({\mathbf {r}}\), \({\mathbf {s}}\), \({\mathbf {p}}\), \({\mathbf {q}}\), \({\mathbf {R}}{\mathbf {x}}\), \({\mathbf {R}}{\mathbf {p}}\) and \({\mathbf {C}}^{-1}{\mathbf {q}}\). Note that the recursion for \({\mathbf {R}}{\mathbf {x}}_{k+1}\) is included to avoid an extra multiplication with \({\mathbf {R}}\). It can be ignored in case \({\mathbf {R}}={\mathbf {I}}\). In this algorithm, only three matrix-vector multiplications are carried out per iteration: \({\mathbf {A}}{\mathbf {p}}_{k+1}\), \({\mathbf {A}}^{\mathrm{H}}{\mathbf {r}}_k\) and \({\mathbf {R}}{\mathbf {p}}_k\). Additionally, one system with \({\mathbf {C}}\) has to be solved (if \({\mathbf {C}}\ne {\mathbf {I}}\)). A slightly different formulation of the GCGLS algorithm can be found in [34].

2.3 GCGME

If \(\tau {\mathbf {R}}\) is invertible, \({\mathbf {x}}\) can be eliminated from Eq. (23), yielding

Subsequently, \({\mathbf {x}}\) can be obtained from \({\mathbf {r}}\) as:

In [25], Arioli and Orban derive a generalization of Craig’s method [7] based on Schur complement (24). Below, we formulate a similar generalization of the CGME method applied to this system. We are not aware this generalization of CGME has been formulated elsewhere.

Here, \({\mathbf {s}}_k\) is the residual of the normal Eq. (24). Note that the original CGME algorithm can be recovered from the generalized CGME algorithm given above by taking \(\frac{1}{\tau }{\mathbf {R}}= {\mathbf {I}}\) and \({\mathbf {C}}= \mathbf {O}\), the zero matrix. Only seven vectors have to be stored, namely \({\mathbf {x}}\), \({\mathbf {r}}\), \({\mathbf {s}}\), \({\mathbf {p}}\), \({\mathbf {q}}\), \({\mathbf {R}}^{-1}{\mathbf {q}}\) and \({\mathbf {C}}{\mathbf {p}}\). Like GCGLS, GCGME needs four matrix operations per iteration: \({\mathbf {C}}{\mathbf {p}}_k\), \({\mathbf {A}}^{\mathrm{H}}{\mathbf {p}}_k\), \({\mathbf {R}}^{-1}{\mathbf {q}}_k\) and \({\mathbf {A}}{\mathbf {R}}^{-1}{\mathbf {q}}_k\). We remark that there is an essential difference between GCGLS and GCGME. GCGLS iterates for the solution vector \({\mathbf {x}},\) and the equality \({\mathbf {r}}_k = {\mathbf {C}}^{-1}({\mathbf {b}}-{\mathbf {A}}{\mathbf {x}}_k)\) is explicitly imposed. The equality \({\mathbf {x}}_k=\frac{1}{\tau }{\mathbf {R}}^{-1}{\mathbf {A}}^{\mathrm{H}}{\mathbf {r}}_k\) is not enforced and is only (approximately) satisfied after convergence. GCGME, on the other hand, iterates for \({\mathbf {r}}_k\). The equality \({\mathbf {x}}_k = \frac{1}{\tau }{\mathbf {R}}^{-1}{\mathbf {A}}^{\mathrm{H}}{\mathbf {r}}_k\) is enforced, while \({\mathbf {r}}_k = {\mathbf {C}}^{-1}({\mathbf {b}}- {\mathbf {A}}{\mathbf {x}}_k)\) is only satisfied approximately after convergence.

2.4 Convergence of GCGLS and GCGME

The convergence of the conjugate gradient method depends on the condition number of the system matrix. Again, suppose that CG is used to solve the system \({\mathbf {Lu}} = {\mathbf {f}}\) for the unknown vector \({\mathbf {u}}\), where \({\mathbf {L}}\) is a Hermitian positive definite (HPD) matrix and \({\mathbf {f}}\) is a known vector. Then, the following classical convergence bound holds [2]:

where \(\kappa _2({\mathbf {L}})\) is the \(\ell _2\)-norm condition number of \({\mathbf {L}}\), which, for HPD matrices, is equal to

in which \(\lambda _{\max }({\mathbf {L}})\) and \(\lambda _{\min }({\mathbf {L}})\) are the largest and smallest eigenvalue of \({\mathbf {L}}\), respectively. In this section, we bound the condition numbers of the two Schur complement matrices in Eqs. (18) and (24) to gain insight into when GCGME can be expected to perform better than GCGLS, and vice versa. Given two HPD matrices \({\mathbf {K}}\) and \({\mathbf {M}}\), the following bound on the condition number holds:

This inequality follows from Weyl’s theorem [37], which states that for eigenvalues of Hermitian matrices \({\mathbf {K}}\) and \({\mathbf {M}}\), the following holds:

Here, \(\lambda _i({\mathbf {K}})\) denotes any eigenvalue of the matrix \({\mathbf {K}}\). For GCGLS, we have that

and, using the following inequalities

with \(\sigma _{\max } ({\mathbf {A}})\) the largest singular value of \({\mathbf {A}}\), we get that

Analogously, for CGME, we have

and using similar manipulations as above we obtain

These inequalities indicate that if

GCGLS can be expected to perform best, and that if

GCGME should be preferred. This latter situation may occur when the regularization term is minimized in the \({\ell}_{p}\)-norm with \(p\in (0,1]\), as we will discuss in the next section.

2.5 Types of regularization

Instead of an \(\ell _2\)-penalty, we will consider the more general case of an \({\ell}_{p}\) penalty with \(p \in (0,2]\). Then, the minimization problem becomes

A vast literature regarding this \(\ell _2{\ell}_{p}\) minimization problem is available. In for example [3, 4, 20, 22], this problem is solved using a majorization–minimization approach. In this work, we will focus on the classical approach using iterative reweighted least squares (IRLS), also known as iterative reweighted norm (IRN), see for example [2], for solving minimization problem (37), in which GCGLS and GCGME can be used as building blocks. Their performances will be compared. We choose the IRLS algorithm for three reasons: its simplicity, the fact that it is a well-known technique and that in this algorithm, the regularization matrix changes in each iteration, which makes it especially interesting for us, because we can test whether GCGME indeed performs better in case Eq. (36) holds. This work is not meant to evaluate the performance of IRLS as a solver for Eq. (37), and we do not compare it with other methods. For completeness, however, we do mention that we could also have chosen to evaluate both approaches as a building block of the split Bregman method [12] for the \(\ell _1\)-regularized problem, for example. In [4], Chan and Liang use CG as a building block for their half-quadratic algorithm that solves Eq. (37) as well. A comparison between GCGLS and GCGME could be carried out in this context too.

IRLS is an iterative method that can solve an \({\ell}_{p}\)-regularized minimization problem by reducing it to a sequence of \(\ell _2\)-regularized minimization problems. Note that for a vector \(\mathbf {m}\) of length N,

so

Furthermore, \({\mathbf {F}}\) is some regularizing matrix. Note that Eq. (37) can be rewritten as:

where

and \(|{\mathbf {F}}{\mathbf {x}}|\) is the element-wise modulus of \({\mathbf {F}}{\mathbf {x}}\). This is simply another instance of minimization problem (17), with \({\mathbf {R}}={\mathbf {F}}^{{H}}{\mathbf {D}}{\mathbf {F}}\). However, now \({\mathbf {R}}\) depends on \({\mathbf {x}}\). So, when the kth iterate \({\mathbf {x}}_k\) is known, \({\mathbf {x}}_{k+1}\) is found as follows:

where

This is repeated until convergence. Furthermore, in Eq. (43), \(\epsilon\) is a small number that is added to the denumerator to prevent division by zero. We will use \(\epsilon = 10^{-6}\). We observe that in each IRLS iteration, we simply encounter an instance of minimization problem (17) again with \({\mathbf {R}}_k = {\mathbf {F}}^{\mathrm{H}}{\mathbf {D}}_k{\mathbf {F}}\), which can be solved using either GCGLS or GCGME. When carrying out calculations with \({\mathbf {D}}_k^{-1}\), we will use

Due to the sparsity-inducing property of the \({\ell}_{p}\) penalty when \(p\le 1\) (see for example [8]), \({\mathbf {D}}_k^{-1} = {\text {diag}}\left( |{\mathbf {F}}{\mathbf {x}}_k| \right)\) will contain an increasing number of entries nearly equal to zero. In cases where \({\mathbf {F}}\) is an invertible matrix, \({\mathbf {R}}_k^{-1} = {\mathbf {F}}^{-1}{\mathbf {D}}_k^{-1}({\mathbf {F}}^{\mathrm{H}})^{-1}\). When GCGME is used, we can take advantage of this structure, instead of calculating \({\mathbf {R}}_k\) and working with its inverse. Moreover, when \({\mathbf {F}}\) is an orthogonal matrix, no additional computations are necessary to compute inverses.

The regularization matrix \({\mathbf {R}}={\mathbf {F}}^{\mathrm{H}}{\mathbf {D}}_k{\mathbf {F}}\) will become ill-conditioned when elements of \({\mathbf {F}}{\mathbf {x}}_k\) become small. Therefore, we expect that, when combined with IRLS, GCGME will perform better than GCGLS for \(p\le 1\). Numerical experiments are carried out to investigate this further.

2.5.1 Different choices for p

We will minimize the following \(\ell _1\)-regularized least-squares problem and the \(\ell _{1/2}\)-regularized least-squares problem to obtain approximations to the optimal solution \({\mathbf {x}}\). For a general \({\mathbf {F}}\), this results in the following two minimization problems:

and

We note that in the latter case, the objective function is not convex which means that the obtained solution does not necessarily correspond to a global minimum, see for example [5]. For each of these two minimization problems, we will consider two different regularization operators.

2.5.2 Regularizing using the identity matrix

First, we set \({\mathbf {F}}={\mathbf {I}}\). In case the \(\ell _1\) penalty is used, the minimization problem reduces to

This is known as least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regularization which was first introduced by Tibshirani in [35]. If the regularization parameter is set to a sufficiently high value, the resulting solution will be sparse. The same holds for the \(\ell _{1/2}\)-regularized minimization problem:

The rationale behind choosing this type of regularization is the fact that the intensity of many pixels in MRI images is equal to 0. In both cases (\(p=1\) and \(p=1/2\)), the regularization matrix reduces to \({\mathbf {R}}_k = {\mathbf {D}}_k = {\text {diag}}\left( \frac{1}{| {\mathbf {x}}_k|^{2-p}} \right)\) and its inverse is simply \({\mathbf {R}}_k^{-1} = {\mathbf {D}}_k^{-1} = {\text {diag}}\left( |{\mathbf {x}}_k|^{2-p} \right)\). This is especially useful for GCGME, because calculating the product of \({\mathbf {R}}^{-1}\) and a vector is trivial in this case.

2.5.3 Regularizing using first-order differences

Additionally, we consider the case where \({\mathbf {F}}\) is a first-order difference matrix \({\mathbf {T}}\) that calculates the values of the jumps between each pair of neighboring pixels. Suppose our image consists of \(n\times n\) pixels. If we define the 1D first-order difference operator \({\mathbf {T}}_{1D}\in \mathbb {R}^{n\times n}\)

the 2D first-order difference matrix is given by:

where \(\otimes\) denotes the Kronecker product. This type of regularization is known as anisotropic total variation regularization. A reason for choosing \({\mathbf {F}}={\mathbf {T}}\) is that neighboring pixels are very likely to have the same values in MR images. This is due to the fact that neighboring pixels tend to represent the same tissue. However, \({\mathbf {T}}\) is not a square matrix, which means that, in the \(\ell _1\) case, \({\mathbf {R}}_k\) has to be calculated explicitly and then inverted when GCGME is used. Although this makes regularization with first-order differences in combination with GCGME less attractive than with GCGLS, we do include this technique to investigate the relative reconstruction quality of this widely used regularization method. The resulting minimization problems are equal to Eqs. (45) and (46) with \({\mathbf {F}}={\mathbf {T}}\):

and

2.5.4 Four different minimization problems

We will investigate all four minimization problems (47), (48), (51) and (52). Since the least-squares term is the same in all four minimization problems, the difference between them lies in the penalty term used, as summarized in Table 2. In each of the four cases, we will use both GCGLS and GCGME to compare their rate of convergence.

2.6 Numerical simulations

For our simulations, we use a simulated magnetic field as shown in Fig. 1a. (We also have access to a measured field map, but it is measured on a very coarse grid, making it unsuitable for our purposes.) The magnetic field within the FoV of 14 cm by 14 cm is clearly inhomogeneous, as shown in Fig. 2. The magnetic field has an approximately quadrupolar profile. This is because the Halbach cylinder is designed to generate a field that is as uniform as possible. However, due to practical limitations, such as the finite length of the cylinder, this uniformity cannot be attained, leading to a quadratic residual field profile. See for example [6, 18]. We do not use a switched linear gradient coil, as is done in conventional MRI. Instead, the inhomogeneous background field is used for readout encoding. For a thorough exploration of the use of non-bijective encoding maps in MRI, we refer to [13, 18, 31,32,33].

Performing slice selection in the presence of a nonhomogeneous background field is nontrivial, but this complication is ignored here. We assume that the entire measured signal originates from one slice. We simulate the signal generation inside the Halbach cylinder using Eqs. (11) and (12). The dwell time is set to \(\varDelta t = 5\times 10^{-6}\), and the readout window is 0.5 ms, leading to 101 data points per measurement. Additionally, the field is rotated by 5° after each individual measurement, so in order to cover a full circle, 72 different angles are considered. We note that this is similar to a radial frequency-domain trajectory dataset in conventional MRI. In [18], quadrupolar fields are used to generate such a dataset. However, the field we are using is only approximately quadrupolar, so it is not a true radial frequency-domain trajectory experiment. The system consists of \(72 \times 101 = 7272\) equations. The numerical phantom of \(64 \times 64\) pixels is shown in Fig. 1b, resulting in a matrix \({\mathbf {A}}\) of size \(7272\times 4096\). We assume that the repetition time \(T_R\) is long enough for the magnetization vector to relax back to its equilibrium. Also, the echo time is assumed to be so short as to make \(T_2\)-weighting negligible.

Since the background field is almost homogeneous in the center, as shown in Fig. 2, we decided to place the object of interest in the numerical phantom off-center. Within a homogeneous region in the field, distinguishing between the different pixels is impossible. Another obstacle in the reconstruction process is the fact that the background field is almost symmetrical in both the x- and the y-axis, potentially leading to aliasing artifacts in the lower half of the image (because the object of interest is placed in the upper half of the image). We could reconstruct by leaving out all the columns in matrix \({\mathbf {A}}\) corresponding to the pixels in the lower half of the image. Another way of circumventing this problem is by using several receiver coils with different sensitivity maps to break the symmetry of the problem [18, 33]. However, we choose not to take these approaches, so we can see how severe these artifacts are for the different objective functions.

The coil sensitivity c is assumed to be constant, so it is left out of the calculations. White Gaussian noise is added, so the covariance matrix \({\mathbf {C}}\) is simply the identity matrix. We assume an SNR of 20. The numerical experiments are carried out using MATLAB version 2015a. Often, CG is stopped once the residual is small enough. However, GCGLS and GCGME are solving different normal equations, so the residuals are different for both methods. Therefore, a comparison using such a stopping criterion would not be fair. Instead, a fixed number of CG iterations is used per IRLS iteration. The value of the regularization parameter \(\tau\) is chosen heuristically. The number of IRLS iterations is set to 10. We consider both 10 and 1000 CG iterations per IRLS iteration. The initial guess \({\mathbf {x}}_0\) in GCGLS (and \({\mathbf {r}}_0\) in GCGME) is the zero vector. During the first IRLS iteration, we set \({\mathbf {D}}={\mathbf {I}}\), which means that \({\mathbf {R}}= {\mathbf {F}}^*{\mathbf {F}}\). After the first IRLS iteration, we calculate the weight matrix \({\mathbf {D}}\) according to Eq. (43). We use warm starts, i.e., we use the final value of our iterate \({\mathbf {x}}_k\) (or \({\mathbf {r}}_k\) for GCGME) of the previous IRLS iteration as an initial guess for the next IRLS iteration.

3 Results and discussion

Table 3 shows the parameters that were chosen for all four different minimization problems. The regularization parameter was chosen heuristically in each case.

All resulting images are shown in Fig. 3. We note that in all cases (except perhaps the \(\Vert {\mathbf {x}}\Vert _{1/2}^{1/2}\) one), GCGME yields a result that resembles the original more than GCGLS does. GCGLS tends to yield aliasing artifacts in the lower half of the image. This effect is less pronounced for the GCGME results, especially when \(\Vert {\mathbf {T}}{\mathbf {x}}\Vert _{1/2}^{1/2}\) is used as the penalty term. The objective function value is plotted as a function of the iteration number in Fig. 4. We see that GCGME attains a lower objective function value in all cases. However, both methods should in theory converge to the same value for the \(\Vert {\mathbf {x}}\Vert _1\)- and \(\Vert {\mathbf {T}}{\mathbf {x}}\Vert _1\)-penalty terms. Evidently, GCGLS has not converged yet. If we increase the number of CG iterations to 1000, GCGLS and GCGME converge to the same result, as can be seen in Appendix B. The GCGME result is the same, whether 10 or 1000 CG iterations are carried out, which means that GCGME has already converged in the first case. However, GCGLS needs a significantly larger number of iterations to converge. In case \({\mathbf {F}}={\mathbf {I}}\), GCGLS and GCGME both need 0.069 s per iteration. When \({\mathbf {F}}={\mathbf {T}}\), GCGME needs slightly more time per iteration than GCGLS: 0.072 versus 0.069 s.

3.1 Discussion of the results

GCGLS needs a large number of CG iterations to converge, while for GCGME, this number is low (typically, 10 is sufficient). This can be explained by the observation that as we get closer to the solution, many elements of the vector \(|{\mathbf {F}}{\mathbf {x}}_k|^{2-p}\) will converge to zero, due to the sparsity-enforcing properties of the \({\ell}_{p}\) penalty when \(p\le 1\). Therefore, \({\mathbf {D}}_k^{-1} = {\text {diag}}\left( |{\mathbf {F}}{\mathbf {x}}_k|^{2-p} \right)\) will contain an increasing number of very small entries, which means that the matrix \({\mathbf {R}}_k = {\mathbf {F}}^{\mathrm{H}} {\mathbf {D}}_k {\mathbf {F}}\) will become more and more ill-conditioned as the number of IRLS iterations grows. That means that, after a few IRLS iterations, \(\kappa _2({\mathbf {R}}_k) \gg \kappa _2({\mathbf {I}})\) will hold, in which case GCGME performs better than GCGLS, which is consistent with our results.

It is interesting to note that when the number of CG iterations for GCGLS is set to 10, GCGLS appears to have reached convergence after 4–5 IRLS iterations, yielding an image with aliasing artifacts in the form of an additional shape in the lower half of the image, as well as regions of intensity in the corners of the image. However, convergence is not actually attained yet. The number of CG iterations needs to be increased to a 1000 before convergence is reached.

We observe that the \(\Vert {\mathbf {T}}{\mathbf {x}}\Vert _{1/2}^{1/2}\) penalty is best at repressing the aliasing artifacts in the lower half of the image.

4 Conclusion

We formulated a general MRI signal model describing the relationship between measured signal and image which is more suitable for low-field MRI because the assumptions that are usually made in high-field MRI do not hold here. The discretized version yields a linear system of equations that is very ill-posed. Regularization is needed to obtain a reasonable solution. We considered the weighted and regularized least-squares problem. A second set of normal equations was derived, which allowed us to generalize the conjugate gradient minimal error (CGME) method to include nontrivial weighting and regularization matrices.

We compared our GCGME method to the classical GCGLS method by applying both to data simulated using our signal model. Different regularization operators were considered: the identity matrix and the anisotropic total variation operator that determines the size of the jumps between neighboring pixels. The regularization term was measured in the \(\ell _1\)-norm and the \(\ell _{\frac{1}{2}}\)-norm, and iterative reweighted least squares (IRLS) was used to solve the resulting minimization problems. In each IRLS iteration, an \(\ell _2\)-regularized minimization problem was solved using GCGLS or GCGME.

GCGME converges much faster than GCGLS, due to the regularization matrix becoming increasingly ill-conditioned as the number of IRLS iterations increases. This makes GCGME the preferred algorithm for our application.

References

Barrett R, Berry M, Chan TF, Demmel J, Donato J, Dongarra J, Eijkhout V, Pozo R, Romine C, Van der Vorst H (1994) Templates for the solution of linear systems: building blocks for iterative methods. SIAM, Philadelphia

Björck Å (1996) Numerical methods for least squares problems. SIAM, Philadelphia

Buccini A, Reichel L (2019) An \(\ell ^2-\ell ^q\) regularization method for large discrete ill-posed problems. J Sci Comput 78(3):1526–1549

Chan RH, Liang HX (2014) Half-quadratic algorithm for \({\ell}_{p}-\ell _q\) problems with applications to TV-\(\ell _1\) image restoration and compressive sensing. In: Bruhn A, Pock T, Tai X-C (eds) Efficient algorithms for global optimization methods in computer vision. Springer, Berlin, pp 78–103

Chen CN, Hoult DI (1989) Biomedical magnetic resonance technology. Hilger, Madison

Cooley CZ, Stockmann JP, Armstrong BD, Sarracanie M, Lev MH, Rosen MS, Wald LL (2015) Two-dimensional imaging in a lightweight portable MRI scanner without gradient coils. Magn Reson Med 73(2):872–883

Craig EJ (1955) The N-step iteration procedures. Stud Appl Math 34(1–4):64–73

Elad M (2010) Sparse and redundant representations: from theory to applications in signal and image processing. Springer, Berlin

Engl HW, Hanke M, Neubauer A (1996) Regularization of inverse problems, vol 375. Springer, Berlin

Fessler JA (2010) Model-based image reconstruction for MRI. IEEE Signal Process Mag 27(4):81–89

Fessler JA, Lee S, Olafsson VT, Shi HR, Noll DC (2005) Toeplitz-based iterative image reconstruction for MRI with correction for magnetic field inhomogeneity. IEEE Trans Signal Process 53(9):3393–3402

Goldstein T, Osher S (2009) The split Bregman method for L1-regularized problems. SIAM J Imaging Sci 2(2):323–343

Haas M, Ullmann P, Schneider J, Post H, Ruhm W, Hennig J, Zaitsev M (2013) PexLoc-parallel excitation using local encoding magnetic fields with nonlinear and nonbijective spatial profiles. Magn Reson Med 70(5):1220–1228

Hanke M (1995) Conjugate gradient type methods for ill-posed problems, vol 327. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Hanke M (1995) The minimal error conjugate gradient method is a regularization method. Proc Am Math Soc 123(11):3487–3497

Hansen PC (1992) Analysis of discrete ill-posed problems by means of the L-curve. SIAM Rev 34(4):561–580

Hansen PC (2010) Discrete inverse problems: insight and algorithms. SIAM, Philadelphia

Hennig J, Welz AM, Schultz G, Korvink J, Liu Z, Speck O, Zaitsev M (2008) Parallel imaging in non-bijective, curvilinear magnetic field gradients: a concept study. Magn Reson Mater Phys Biol Med 21(1–2):5

Hestenes MR, Stiefel E (1952) Methods of conjugate gradients for solving linear systems, vol 49. NBS, Gaithersburg, MD

Huang G, Lanza A, Morigi S, Reichel L, Sgallari F (2017) Majorization–minimization generalized Krylov subspace methods for \({\ell}_{p}-\ell _q\) optimization applied to image restoration. BIT Numer Math 57:351–378

King J (1989) A minimal error conjugate gradient method for ill-posed problems. J Optim Theory Appl 60(2):297–304

Lanza A, Morigi S, Reichel L, Sgallari F (2015) A generalized Krylov subspace method for \({\ell}_{p}-\ell _q\) minimization. SIAM J Sci Comput 37(5):S30–S50

Liang ZP, Lauterbur PC (2000) Principles of magnetic resonance imaging: a signal processing perspective. SPIE Optical Engineering Press, Bellingham

Nemirovskii AS (1986) The regularizing properties of the adjoint gradient method in ill-posed problems. USSR Comput Math Math Phys 26(2):7–16

Orban D, Arioli M (2017) Iterative solution of symmetric quasi-definite linear systems, vol 3. SIAM, Philadelphia

Pruessmann KP (2006) Encoding and reconstruction in parallel MRI. NMR Biomed Int J Devoted Dev Appl Magn Reson In Vivo 19(3):288–299

Pruessmann KP, Weiger M, Börnert P, Boesiger P (2001) Advances in sensitivity encoding with arbitrary k-space trajectories. Magn Reson Med Off J Int Soc Magn Reson Med 46(4):638–651

Ramani S, Fessler JA (2010) Parallel MR image reconstruction using augmented lagrangian methods. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 30(3):694–706

Saad Y (2003) Iterative methods for sparse linear systems. SIAM, Philadelphia

Saunders MA (1995) Solution of sparse rectangular systems using LSQR and CRAIG. BIT Numer Math 35(4):588–604

Schultz G (2013) Magnetic resonance imaging with nonlinear gradient fields: signal encoding and image reconstruction. Springer, Berlin

Schultz G, Gallichan D, Weber H, Witschey WR, Honal M, Hennig J, Zaitsev M (2015) Image reconstruction in k-space from MR data encoded with ambiguous gradient fields. Magn Reson Med 73(2):857–864

Schultz G, Ullmann P, Lehr H, Welz AM, Hennig J, Zaitsev M (2010) Reconstruction of MRI data encoded with arbitrarily shaped, curvilinear, nonbijective magnetic fields. Magn Reson Med 64(5):1390–1403

Sutton BP, Noll DC, Fessler JA (2003) Fast, iterative image reconstruction for MRI in the presence of field inhomogeneities. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 22(2):178–188

Tibshirani R (1996) Regression shrinkage and selection via the LASSO. J R Stat Soc Ser B (Methodol) 58:267–288

Tikhonov AN (1963) On the solution of ill-posed problems and the method of regularization. Dokl Akad Nauk 151:501–504

Weyl H (1912) Das asymptotische verteilungsgesetz der eigenwerte linearer partieller differentialgleichungen (mit einer anwendung auf die theorie der hohlraumstrahlung). Mathe Ann 71(4):441–479

Ye JC, Tak S, Han Y, Park HW (2007) Projection reconstruction MR imaging using FOCUSS. Magn Reson Med Off J Int Soc Magn Reson Med 57(4):764–775

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the anonymous referees for their detailed comments which helped us improve our manuscript. We would like to express our gratitude to Peter Sonneveld for useful discussions regarding Krylov methods. We also thank the low-field MRI team members of the Leiden University Medical Center, the Electronic and Mechanical Support Division (DEMO) in Delft, Pennsylvania State University and Mbarara University of Science and Technology for their insight and expertise.

Funding

This research is supported by NWO-WOTRO (Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research) under Grant W07.303.101 and by the TU Delft | Global Initiative, a program of the Delft University of Technology to boost Science and Technology for Global Development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Optimality property of GCGLS and GCGME

Suppose we have a linear system of equations \({\mathbf {L}}{\mathbf {u}}= {\mathbf {f}}\) with solution \({\mathbf {u}}^*\). \({\mathbf {L}}\) is a hermitian positive definite (HPD) matrix. Then, at iteration k, the conjugate gradient method finds \({\mathbf {u}}_k\) such that \(||{\mathbf {u}}_k - {\mathbf {u}}^*||_{\mathbf {L}}\), the error induced by the system matrix \({\mathbf {L}}\), is minimized over the Krylov subspace \({\mathbf {u}}_0 + \mathcal {K}_k({\mathbf {L}},{\mathbf {f}}):= {\mathbf {u}}_0+{\text {span}}\{{\mathbf {f}},{\mathbf {L}}{\mathbf {f}},{\mathbf {L}}^2{\mathbf {f}},\ldots ,{\mathbf {L}}^{k-1}{\mathbf {f}}\}\). This means that, in every iteration, GCGLS minimizes

for \({\mathbf {x}}_k - {\mathbf {x}}_0 \in \mathcal{K}_k({\mathbf {A}}^{\mathrm{H}} {\mathbf {C}}^{-1} {\mathbf {A}}+ \tau {\mathbf {R}}, {\mathbf {A}}^{\mathrm{H}}{\mathbf {C}}^{-1} {\mathbf {r}}_0 + \tau {\mathbf {R}}{\mathbf {x}}_0)\). For every iteration of GCGME, the following holds:

with \({\mathbf {r}}_k - {\mathbf {r}}_0 \in \mathcal{K}_k({\mathbf {r}}_0,\frac{1}{\tau } {\mathbf {A}}{\mathbf {R}}^{-1}{\mathbf {A}}^{\mathrm{H}} + {\mathbf {C}})\). Note that GCGLS and GCGME minimize the same weighted combination of the errors in the residual and in the solution, but over different subspaces and under different constraints.

Appendix 2: Increasing the number of CG iterations per IRLS iteration

1.1 Appendix 2.1: \(\ell _1\)-penalty with \({\mathbf {F}}={\mathbf {I}}\)

See Fig. 5.

Reconstruction results with \({\mathbf {F}}={\mathbf {I}}\), \(\tau = 3 \times 10^{-1}\) and 1000 CG iterations per IRLS iteration. In the rightmost figure, the value of objective function (47) is plotted as a function of the iteration number. The vertical black lines indicate the start of a new IRLS iteration

1.2 Appendix 2.2: \(\ell _1\)-penalty with \({\mathbf {F}}={\mathbf {T}}\)

See Fig. 6.

Reconstruction results with \({\mathbf {F}}={\mathbf {T}}\), \(\tau = 2\times 10^{-2}\) and 1000 CG iterations per IRLS iteration. In the rightmost figure, the value of objective function (51) is plotted as a function of the iteration number. The vertical black lines indicate the start of a new IRLS iteration

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

de Leeuw den Bouter, M.L., van Gijzen, M.B. & Remis, R.F. Conjugate gradient variants for \({\ell}_{p}\)-regularized image reconstruction in low-field MRI. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 1736 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1670-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1670-2