Abstract

Metal nitrides (and particularly TiN) are among the most extensively investigated proton exchange membrane fuel cell bipolar plates (BP) coatings. The most employed methods of nitrides coating deposition are various modifications of physical vapor deposition (PVD), while different types of stainless steels are the most common BP materials coated with TiN PVD films. In the current work, we report on the integrity maintenance of TiN PVD coating of AISI416, considering this as a clue to the sustainability of such a film. The advantage of this combination lies in the fact that the coefficients of thermal expansion (CTE) of this alloy is close to the CTE of the TiN film. Thus, the thermal stresses of such coating are expected to be minimal, as well as related coating cracks. We conducted a thorough surface analysis of roughness evolution in the course of BP corrosion process, investigating different initial surface pretreatments. Finally, we found that fine mirror-like polished BP substrate prior to deposition is essential for TiN film’s integrity during corrosion analysis time.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Bipolar plates (BP) are an important part of a polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM) hydrogen fuel cell (FC) power stack; they furnish electrical connection of the cells in the stack, support thermal management of the cells during operation, provide cells with hydrogen and oxygen, and remove water byproduct in the course of operation. BP should demonstrate high material conductivity, low areal interfacial contact resistance (ICR) at the gas diffusion layer (GDL)/BP interface, and should be corrosion-resistant in the PEM FC environments—DOE target for corrosion current is ≤ 0.1 μA/cm2; the corresponding corrosion test comprises of polarizing the item at + 0.6 V [vs. Ag/AgCl] in the electrolyte with pH3, which contains 0.1 ppm HF, over 24 h at 80 °C [1].

ICR value and its evolution with operation time is one of the most important parameters governing the feasibility of BP for commercially usage in a viable FC; along with electrode catalyst efficiency, the ICR value controls a substantial part of the overall FC losses [2]. The US Department of Energy (DOE) targets are ≥ 100 S/cm for bulk BP material conductivity, and ICR ≤ 10 mΩ cm2 (under the above corrosion test) [1]. Currently, corrosion resistance and electrical—related properties of graphite-based BPs are considered as a benchmark by which other PEM FC BPs are being rated since graphite BP demonstrate excellent bulk conductivity, outstandingly low ICR and adequate high corrosion resistance [3]. At the same time, graphite has substantial drawbacks. Indeed, each PEM FC develops impractically low voltage (even theoretical PEM FC voltage is just 1.23 V), so a common commercially viable PEM FC stack will be comprised of several tens of individual cells, thus BP material should demonstrate excellent manufacturability and be cost-effective for BP mass production. At the same time, graphite has poor machinability which makes inadequate from this point. The other aspect is poor graphite mechanical features that require graphite-based BP to be thick and heavy making such BP comprise almost 90% of PEMFC stack [4].

The above matter suggests that application of metal BP (aluminum, stainless steel, nickel, titanium, etc.) would be advantageous from production and PEMFC stack point of view. It was revealed, though, that metals which demonstrate low corrosion rate in the aggressive PEM FC environment, such as stainless steels and titanium, become covered with oxide layers. While these layers protect the BP from corrosion they drastically increase their ICR. A good example of such materials are various stainless steels; these are materials of choice for many applications because of their high mechanical strength, good machinability, excellent corrosion resistance, and fairly low cost; at the same time, stainless steel BP demonstrate high ICR that grow fast in FC environment with time.

Until now, a significant attention was devoted to the development of corrosion-resistant and conductive coatings for metallic BP in order to prevent BP corrosion, keeping the lowest ICR during FC operation. It turns out that development of a protective coating like extremely thin noble metal films, nitride and carbide-based films, which improves the corrosion resistance of the metal BP without compromising ICR [5, 6], is a challenging task. Metal nitrides (and particularly TiN) are among the most extensively investigated BP coatings, due to their exceptional metal-type conductivity and excellent corrosion stability; the most employed methods of nitride coating deposition are various modifications of physical vapor deposition (PVD) [7, 8]. Different types of stainless steels are the most common BP materials coated with TiN PVD films; these are ANSI316L, ANSI304, AISI321, AINSI410, AISI434, AISI436, AISI441, AISI444, AISI446 and also titanium [6, 8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

Currently, it is well established that the corrosion of a TiN coated metal starts via the penetration of the corroding agent through different coating defects, followed by a localized corrosion of the substrate and subsequent successive disruption and crumbling of the coating [8, 15,16,17,18,19,20]. Typical PVD coating defects are of a micron-scale sizes, and thus the substrate corrosion at coating pits has all the features of confined (pitting, crevice, gap) corrosion. The specific attribute of such corrosion is that the concentrations of the corroding agents (H+, halogen ions) inside such confined areas are usually substantially higher than in the ambient milieu [21], therefore most of the metallic substrates are prone to such pitting corrosion; e.g., if the ambient sulfuric acid solution holds a pH value of 3, the solution inside the thin gap may possess a pH value of 0.4 in the course of crevice corrosion of stainless steel [22]. This feature makes it important to focus on preparation of defect-free TiN films, without relying on self-healing features of the substrate material (being stainless steels and titanium).

Generally, PVD coatings demonstrate two kinds of defects. The origin of the first type is the intrinsic feature of the PVD coating process; namely, the defects appear because of screening of some substrate areas from accessing of vapor stream [23]. The driving force for the second type defects appearance is an uneven thermal expansion of the PVD film and the substrate [24, 25]. Both types of defects may serve as starting points for BP corrosion [26]. Regarding thermal expansion/contraction related defects, usually PVD process requires substrate heating (up to several hundred centigrade) and cooling down afterward. Additionally, the concentration of coating defects may sometimes be decreased by annealing [27, 28], which moderates the corrosion [29]; at the same time, this thermo-treatment suggests additional substrate heating/cooling cycles. These temperature variations form stresses, which originate from different values of thermal expansion/contraction during heating/cooling of the treated BP. The stresses might result in cracks, no matter are the stresses compressive or tensile in nature. Also, PEMFC undergo periodical heating/cooling cycles in the course of operation, and these thermal cycles impose an additional stress on the BP coating if the coefficients of thermal expansion (CTEs) of coating and bulk BP material are different [30, 31]. Thermal stresses not only contribute to the morphological degradation of the film, but also may promote pitting corrosion of TiN coated material [26].

In the current work, we are focusing on the maintenance of the integrity of the corrosion protective and conductive PVD coating, considering this as a clue to the sustainability of such film; we are focusing on PVD coating of AISI416 stainless steel with TiN under different surface pretreatments. AISI416’s CTE (9.9 × 10−6/°C [32]) is close to TiN’s CTE (9.4 × 10−6/°C [33]) thus thermal stresses of such coating are expected to be minimal, as well as related coating cracks. Besides, a due emphasis is given to the investigation of the BP surface roughness evolution in the course of BP corrosion; whereas roughness influence of contacting surfaces on ICR is well reported [34,35,36,37], up to now not much attention was paid to roughness evolution of BP surface under the influence of the corrosion process itself.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Samples preparation

The samples were cut from a 12.7 mm diameter AISI416 rod to form 3 mm thick discs. One side of the samples was grinded up to P180 grit or P1200 grit. Samples were also polished using diamond abrasive 1 µm as the last polish step, resulting in a mirror-like surface. Both rough and fine polished samples were coated with a thin TiN film (0.25 μm thick) using PVD. Several samples remained uncoated for comparison. The PVD coating was carried out via magnetron (200 W power) sputtering using a high purity TiN target (99.99% of TiN) in a N2/Ar = 1/50 environment (ATC-2200 sputtering system, AJA International Co). The process was maintained at 400 °C to have optimal conduction properties.

2.2 Samples studying and evaluation

Corrosion tests were conducted using a 3-electrode cell; a Platinum wire as the counter electrode and Ag/AgCl as the reference electrode. The test electrolyte is a solution of 10−3 M H2SO4 and 2 ppm F−. The cell was open to the atmosphere and was kept at room temperature. The cell design was so that only the treated side of the sample was exposed to the electrolyte. The corrosion test procedure comprised of polarization at + 0.6 VAg/AgCl for a preset time. The morphology of the sample working surface was observed before and after corrosion tests as well as ICR measurements.

2.3 Samples characterization

Sample surface was examined with SEM (Zeiss Ultra-Plus HRSEM and FEI Quanta200 SEM), EDS (Oxford SDD EDS), AFM (Agilent 5500) and XRD [Rigaku Smartlab, Cu-K alpha (1.5418Å)]; ICR versus pressure curves were measured using a home-made installation presented in Scheme S1. A constant current IConst was applied between a copper plate and a copper rod and the voltage VM was measured. The ICR at each pressure point was estimated as \(ICR = \frac{{V_{M} }}{{I_{Const} }}\). The installation is a simplified version of the assembly employed in [38] (different modifications of such assembly are frequently used for BP ICR measurements). Preliminary experiments demonstrate that the values \(R_{no\_Toray} = \frac{{V_{M}^{no Toray} }}{{I_{Const} }}\) and \(R_{no\_sample} = \frac{{V_{M}^{no sample} }}{{I_{Const} }}\), which were measured after removing of the Toray paper spacer and the sample from the installation (Scheme S1) correspondingly, are substantially smaller than all ICR values in the investigated range; Rno_Toray and Rno_sample were below 10% of ICR values in this range, so the corresponding corrections don’t influence the article discourse and conclusions. ICR results are presented as curves of ICR (Ohm cm2) versus applied pressure P (kg cm−2).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization of SS416 substrates subsequent to TiN coating

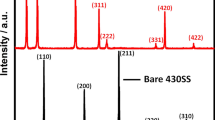

Figure 1 presents XRD pattern of TiN coated AISI416 and shows that the deposited layer has a crystalline structure that corresponds to TiN Osbornite diffraction with Fe peaks that are related to the steel substrate. It confirms that the PVD process was successful in plating the steel with a crystalline TiN. Layer thickness was estimated to be 264.8 ± 23 nm, the cross-section images with all thickness measurements are shown in Fig. S1. The thickness is uniform along the sample and all samples were made under the same conditions. Thus, it is safe to conclude that all coated samples were coated with a layer ~ 0.25 µm as described in the experimental section.

Figure 2 shows the impact of heat treatment on two different substrates, AISI416 and SS316. Both samples were heated up to 600 °C in N2 environment for 1 h. The coating on AISI416 sustained its integrity under the heat treatment though it formed some islands (Fig. 2b) whereas the coating on SS316 was severally damaged and broke off the substrate (Fig. 2d). The reason for this behavior is CTE mismatch between substrate and coating. As explained, there is only a small mismatch between TiN and AISI416 (0.5 × 10−6/°C) which make it easier to maintain integrity. SS316, on the other hand, has bigger difference (~ 6 × 10−6/°C) as its CTE is 16 × 10−6/°C [39]. This fact justifies the choice of AISI416 over the more commonly used SS316 alloy.

3.2 ICR of a metal PVD: coated with TiN film

Figure 3a demonstrates the dependence of ICR in metal surface treatment where smoother metal surface (P1200 grit polish) offers higher ICR than rougher surface (P180 grit polish). ICR of metal/Toray contacts passes through minimum at some metal surface roughness, and the smoothest metal BP surface does not necessarily offer the lowest ICR [34]. There are many who report that ICR diminishes with decreasing surface roughness and then regains resistivity when the surface gets smoother [36,37,38,39].

a ICR plots for AISI416 samples with different surface treatment; b–d 1D AFM—patterns of Toray paper and AISI416 surface textures representing the conformity of: b Toray paper with P180 treated metal; c Toray paper with P1200 treated metal; d Toray paper surface with uncoated surface and coated surface; the Figure scale is based on the experimental AFM-image

The reason behind that is that Toray paper’s surface texture fits the roughly textured (P180) sample surface at the micron-scale, and this conformity provides electrical contacts with a substantial contact area; a smaller contact area is obtained when using a smoother surface (P1200) [39]. Figure 3b and c illustrates this provision. Figure 3a also indicates that ICR of TiN coated samples differs from ICR of bare AISI416 samples; ICR of P1200 pretreated surface substantially diminishes after coating, more than 10 times less (from 270 to 18 mΩ at 15 kg/cm2.; the latter number is generally comparable to DOE 2020’s target). It is noteworthy that the ICR curve for the coated sample is actually very close to the corresponding curve of the P180 bare sample. It suggests that the reason for this ICR difference resides not in the high conductivity of the TiN film but in the changes of the sub-micron surface geometry after PVD coating (see Fig. 3d).

Toray paper is made of entangled carbon fibers on the micron-scale; the fibers are composed of thin carbon strands on the sub-micron and nanometer scales, as presented in Fig. S2. The contact topology on the sub-micron and nanometer scales depends on the multiscale surface roughness of the contacting members, and self-similar surface fractal dimensions [39]. The multi-scale roughness may be adequately described by area excess (Aexcess) which is the excess of the measured surface area Ameasured over the apparent surface area Aapparent:

Figure 4a presents AFM images for P180 and P1200 grit samples with and without TiN coating. The visual surface shows that what appears to be a uniform and flat surface at the macro scale turns to have a larger effective surface area. Furthermore, coated samples have prickly surface in contrary to a relatively smooth surface of the bare sample. The results are in consistence with the literature data regarding surface roughness increase upon metal nitride PVD coating [40, 41].

Table 1 summarizes the Aexcess results and support the hypothesis above. Since Aexcess has only a slight difference between coated and uncoated P180 samples their corresponding ICR curves doesn’t differ much as well. With P1200 samples on the other hand, the difference is noticeable—more than tenfold—thus their ICR curves also differ. Moreover, carbon paper morphology (Fig. S2) and sample surface morphology (Fig. 4a) correlation suggests that whereas bare sample contacts only with carbon fiber surface, TiN coated sharp prickles may penetrate through inter-strand space, increasing the physical contact area. Considering TiN hardness, this process is likely to happen [42].

It is commonly accepted that smoother sample surface results in less defects of its PVD coating [23, 43]; SEM inspection demonstrates that the same is true for the conditions of our experiments (Figs. 4b, 2a). As indicated above, coating defects act as origin points for PVD film detachment and thus account for ICR degradation even if they initially occupy only a small portion of the surface area. Hence, it is beneficial that a smooth sample surface turns to be rough enough upon PVD TiN coating; in fact, initially smooth substrate surface makes film’s integrity better, thus more protective, while the coating improves the ICR of the smooth surface.

3.3 ICR evolution of a pristine AISI 416 surface upon exposure to a corrosive environment

Surface morphology evolution of bare AISI416 samples (P1200 grit) is presented in Fig. 5. After 20 h of corrosion test the surface demonstrates inhomogeneous degradation and is covered with numerous pits; the pitting-related mechanism of stainless-steel electrochemical corrosion is now commonly accepted; pits density (number of pits per area unit) grows with time [44]. The typical pit size including the damaged areas around them is between 20 and 40 μm and their depth is usually shallow, ~ 5% of their linear size [45]. The damaged area covers ~ 30% of the total surface area. Figure 5c demonstrates that corrosion test substantially diminishes ICR at first, after 1 h polarization; similar effect of corrosion test on ICR was reported regarding AISI316 sample [46]. After this initial drop the ICR grows again and persists to be slightly below the starting value even after 20 h of polarization.

It is well known that passive films on stainless steels promptly grow thicker during anodic polarization; it demonstrates a substantial electrical resistance raise of more than an order of magnitude [47] over polarization time. Whereas these results were reported for AISI316 in borate buffer, the authors had also showed that the oxide film (a few nm thick) contained predominantly iron oxides/hydroxides and chromium oxide; since chromium content of AISI316 is close to that of AISI416 there is a good ground to suggest that AISI416’s passive films would demonstrate similar electrical properties. To explain the effect, it may be suggested that surface corrosion occurs in two pathways:

-

The first pathway is pitting corrosion; besides the insulating nature of the passive film inside the pit and in its vicinity, pit configuration and distribution does not prevent the contact between Toray paper and the unaffected areas. The typical pit size is between 20 ÷ 40 μm while typical distance between pits is between 50 ÷ 80 μm. Pitting corrosion affected area comprises 30% of the total sample surface after 20 h of polarization, as estimated from SEM image.

-

The second pathway is related to the inter-pits plateau (~ 70% of the total area). This surface was etched out to form a rough texture (Fig. 5d). As stated earlier, the presence of such texture implies a low ICR.

Since texture formation and insulating passive film growth are on different time scales, it may not be suggested that one is accompanied by the other. ICR measurements shows that the resistance drops initially and only than gradual ICR increase is observed. Meaning, the texture first appears, decreasing the ICR, followed by passive film growth that originating ICR increase. The value of Aexcess of the polarized uncoated P1200 sample is higher than that of a pristine sample, and it supports the above mechanism.

This explanation is at variance with another statement, reporting the influence of corrosion on the ICR of 316L, 317L, 349 and 904L stainless-steels [48]; the author’s conclusion that the interfacial contact resistance is determined only by the appearance of the passive film on stainless steel surface seemingly disregards the influence of the surface texture on the ICR.

3.4 ICR evolution of TiN coated AISI 416 surface upon exposure to a corrosive environment

Surface morphology evolution of TiN coated AISI416 samples (P1200 treated) is presented in Fig. 6. After 40 h of corrosion evaluation, pits are sparsely distributed across the surface. They seem to initiate from coating defects, as opposed to uncoated AISI416 sample (Fig. 5b).

Figure 7a demonstrates that during polarization ICR practically persists after 20 h of polarization, and then starts growing gradually; the initial ICR plateau relates to roughness evolution, which increases after the first 20 h of corrosion testing; this increase is favorable for ICR drop and is counterbalancing the corrosion, and this is well demonstrated in Fig. 7b and Table 1. The value of Aexcess growth after 20 h polarization explains the slightly decreased ICR. After 40 h polarization, the ICR rises even though Aexcess grows as well, indicating that the tradeoff between newly available electrical contacts and insulating areas is in favor of the insulation, thus resistivity is higher. After 80 h polarization ICR persists its growth. There is a large increase in Aexcess since the coating degrades and peels off hence reducing electrical contact while increasing the overall area.

Surface defects are the main reason for ICR growth upon corrosion since pit holes initiate from them and further propagate with polarization time. Coating integrity gets compromised during pit propagation and as seen, has great impact on ICR. Therefore, some samples were polished until they were reflective as mirrors before coating. Figure 8 shows (a) ICR and (b) surface evolution during polarization. ICR seems to be retentive even after 120 h of polarization. It is worth noting that the ICR curves in Fig. 8a are averaging at least three samples for each polarization time and that the standard deviation between 10 and 25 kg cm−2 is one order of magnitude lower than the corresponding ICR value. The reason for higher standard deviation at lower pressures is only because the pressure doesn’t distribute evenly for each sample until a certain point when it converges. Surface morphology doesn’t change greatly (Fig. 8b), which confirms that the coating is well-adhered to the steel substrate and preserves its integrity.

In terms of Aexcess value, the relative excess area remains quite the same (Table 1) because no severe degradation occurs. Figure 9 presents SEM micrographs of the surfaces under corrosion and little to none pit holes are observed. Additionally, micrographs from similar samples are visible in Fig. S3-S5, showing the same behavior for all tested samples. The SEM micrographs assure the statements above, even though some pit holes are created after 20 h there is no further propagation. One can assume that film’s enhanced adhesion keeps the surface from exposure to the electrolyte and pit propagation does not occur to the same extent of P1200 polished samples. Instead, a passive layer is created on pit walls and prevent further corrosion. The slight rise of ICR can be related to those passive spots and support this theory.

4 Conclusions

We report in this work on the durability and sustainability of two materials coupling that may constitutes the next generation of bi-polar plates: TiN PVD coatings onto AISI416. The advantage of joining and matching between these two materials lies in the fact that the values of coefficients of thermal expansion (CTE) of the two materials are similar. Thus, the thermal stresses of such coating are expected to be minimal, as well as the related coating cracks. Our work derived the following pointed list of conclusions:

From the point of ICR, the uncoated AISI416 stainless-steel corrosion behavior demonstrates a complex characteristic and exerts changes in two different levels at the surface. The First level is related to the pitting corrosion through susceptible spots at the surface. The corresponding pits are sized in the range of 10–40 μm. These pits are densely distributed across the surface area, having a significant share of the surface (around 30%). This portion grows with corrosion time and the surface insulating oxides are linked to this pitting corrosion. The Second level is related to the corrosion roughening of the surface, where surface morphology transformation is useful in diminishing ICR. This effect takes place along the insulating oxide expansion across the surface and thickening.

Overall, the ICR values measured depend on the balance of these two processes and one can expect a competition between the two phenomena as exposure time to the corrosive environment increases. TiN PVD coating onto smoothly polished substrates offers a favorable increase in the surface roughness, which decreases the corresponding ICR. This fact allows the preparation of a fine-polished surface before deposition to diminish deposition defects or post-deposition defect initiation from prior surficial defects. Minimizing defect sources prevent corroding agents from penetrating through the protective layer and corrode the AISI416 substrate surface. The better adhesion resulted by deposition on top of fine-polished surface also hinders corrosion propagation while still maintaining low ICR.

The achieved ICR stability upon exposure to the corrosive environment is still below the DOE target; any future works on the topic should consider strengthening the TiN coating corrosion durability by a mitigation of the corrosive agents’ accessibility to the inevitable pin-holes being produced during the PVD coating process of the metallic substrates.

References

Hydrogen storage technologies roadmap, fuel cell technical team roadmap, June 2013. https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2014/02/f8/fctt_roadmap_june2013.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2019

Zhang L, Liu Y, Song H, Wang S, Zhou Y, Hu SJ (2006) Estimation of contact resistance in proton exchange membrane fuel cells. J Power Sources 162(2):1165–1171

Laedre S, Kongstein OE, Oedegaard A, Seland F, Karoliussen H (2013) In situ and ex situ contact resistance measurements of stainless steel bipolar plates for PEM fuel cells. ECS Trans 50(2):829–839. https://doi.org/10.1149/2.1511912jes

Li X, Sabir I (2005) Review of bipolar plates in PEM fuel cells: flow-field designs. Int J Hydrog Energy 30(4):359–371

Karimi S, Fraser N, Roberts B, Foulkes FR (2012) A review of metallic bipolar plates for proton exchange membrane fuel cells: materials and fabrication methods. Adv Mater Sci Eng. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/828070

Asri NF, Husaini T, Sulong AB, Majlan EH, Daud WRW (2017) Coating of stainless steel and titanium bipolar plates for anticorrosion in PEMFC: a review. Int J Hydrog Energy 42(14):9135–9148

Wang H, Turner JA (2010) Reviewing metallic PEMFC bipolar plates. Fuel Cells 10(4):510–519

Antunes RA, Oliveira MCL, Ett G, Ett V (2010) Corrosion of metal bipolar plates for PEM fuel cells: a review. Int J Hydrog Energy 35(8):3632–3647

Ho WY, Pan HJ, Chang CL, Wang DY, Hwang JJ (2007) Corrosion and electrical properties of multi-layered coatings on stainless steel for PEMFC bipolar plate applications. Surf Coat Technol 202(4–7):1297–1301

Kahraman H, Cevik I, Dündar F, Ficici F (2016) The corrosion resistance behaviors of metallic bipolar plates for PEMFC coated with physical vapor deposition (PVD): an experimental study. Arab J Sci Eng 41(5):1961–1968

Wang Y, Northwood DO (2009) Effect of substrate material on the corrosion of TiN-coated stainless steels in simulated anode and cathode environments of proton exchange membrane fuel cells. J Power Sources 191(2):483–488

Wang H, Turner JA (2004) Ferritic stainless steels as bipolar plate material for polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells. J Power Sources 128(2):193–200

Zhang D, Duan L, Guo L, Wang Z, Zhao J, Tuan WH, Niihara K (2011) TiN-coated titanium as the bipolar plate for PEMFC by multi-arc ion plating. Int J Hydrog Energy 36(15):9155–9161

Ren Z, Zhang D, Wang Z (2012) Stacks with TiN/titanium as the bipolar plate for PEMFCs. Energy 48(1):577–581

Milošev I, Navinšek B (1994) A corrosion study of TiN (physical vapour deposition) hard coatings deposited on various substrates. Surf Coat Technol 63(3):173–180

Yang D, Liu C, Liu X, Qi M, Lin G (2005) EIS diagnosis on the corrosion behavior of TiN coated NiTi surgical alloy. Curr Appl Phys 5(5):417–421

Altun H, Sen S (2006) The effect of PVD coatings on the corrosion behaviour of AZ91 magnesium alloy. Mater Des 27(10):1174–1179

Flores JF, Valdez SB, Schorr M, Olaya JJ (2006) Corrosion protection of steels by PVD TaN thin films. Anti-Corros Methods Mater 53(2):88–94

Fenker M, Balzer M, Kappl H (2014) Corrosion protection with hard coatings on steel: past approaches and current research efforts. Surf Coat Technol 257:182–205

Balzer M (2015) Identification of the growth defects responsible for pitting corrosion on sputter-coated steel samples by large area high resolution mapping. Thin Solid Films 581:99–106

Nishimoto M, Ogawa J, Muto I, Sugawara Y, Hara N (2016) Simultaneous visualization of pH and Cl− distributions inside the crevice of stainless steel. Corros Sci 106:298–302

Kaji T, Sekiai T, Muto I, Sugawara Y, Hara N (2012) Visualization of pH and pCl distributions: initiation and propagation criteria for crevice corrosion of stainless steel. J Electrochem Soc 159(7):C289–C297

Mattox DM (1996) Surface effects on the growth, adhesion and properties of reactively deposited hard coatings. Surf Coat Technol 81(1):8–16

Woodman AS, Jayne KD, Anderson EB, Kimble MC (1999) Development of corrosion-resistant coatings for fuel cell bipolar plates. In: AESF SUR FIN-proceedings. American Electroplaters and Surface Finishers Society Inc., pp 717–726

Bielawski M, Seo D (2005) Residual stress development in UMS TiN coatings. Surf Coat Technol 200(5–6):1476–1482

Dranenko AS, Lavrenko VA, Talash VN (2013) Corrosion resistance of TiN films in 3% NaCl solution. Powder Metall Met Ceram 52(3–4):223–227

Tung HM, Huang JH, Tsai DG, Ai CF, Yu GP (2009) Hardness and residual stress in nanocrystalline ZrN films: effect of bias voltage and heat treatment. Mater Sci Eng A 500(1–2):104–108

Huang JH, Yu KJ, Sit P, Yu GP (2006) Heat treatment of nanocrystalline TiN films deposited by unbalanced magnetron sputtering. Surf Coat Technol 200(14–15):4291–4299

Zhao X, Yan D, Li S, Lu C (2011) The effect of heat treatment on the electrochemical corrosion behavior of reactive plasma-sprayed TiN coatings. Appl Surf Sci 257(23):10078–10083

Yuan XZ, Li H, Zhang S, Martin J, Wang H (2011) A review of polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell durability test protocols. J Power Sources 196(22):9107–9116

Ruiu T, Dreizler AM, Mitzel J, Gülzow E (2016) Evaluation of a 2.5 kWel automotive low temperature PEM fuel cell stack with extended operating temperature range up to 120 °C. J Power Sources 303:257–266

https://www.makeitfrom.com/material-properties/AISI-416-1.4005-X12CrS13-S41600-Stainless-Steel. Accessed 19 May 2019

BryCoat Inc. http://www.brycoat.com/surface-engineering/brycoat-pvd-coating-solutions/brycoat-titanium-nitride-tin-coatings/brycoat-titanium-nitride-tin-coatings/. Accessed 19 May 2019

Kraytsberg A, Auinat M, Ein-Eli Y (2007) Reduced contact resistance of PEM fuel cell’s bipolar plates via surface texturing. J Power Sources 164(2):697–703

Avasarala B, Haldar P (2009) Effect of surface roughness of composite bipolar plates on the contact resistance of a proton exchange membrane fuel cell. J Power Sources 188(1):225–229

André J, Antoni L, Petit JP, De Vito E, Montani A (2009) Electrical contact resistance between stainless steel bipolar plate and carbon felt in PEFC: a comprehensive study. Int J Hydrog Energy 34(7):3125–3133

Kim KM, Kim SN, Kim JH, Lee YY, Kim KY (2012) Study on surface topography of 446 M stainless steel as a bipolar plate on interfacial contact resistance of polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell. J Power Sources 220:42–46

Davies DP, Adcock PL, Turpin M, Rowen SJ (2000) Bipolar plate materials for solid polymer fuel cells. J Appl Electrochem 30(1):101–105

Swamy T, Kumbur EC, Mench MM (2011) Investigation of bipolar plate and diffusion media interfacial structure in PEFCs: a fractal geometry approach. Electrochim Acta 56(8):3060–3070

Huang RX, Qi ZB, Sun P, Wang ZC, Wu CH (2011) Influence of substrate roughness on structure and mechanical property of TiAlN coating fabricated by cathodic arc evaporation. Phys Procedia 18:160–167

Gåhlin R, Bromark M, Hedenqvist P, Hogmark S, Håkansson G (1995) Properties of TiN and CrN coatings deposited at low temperature using reactive arc-evaporation. Surf Coat Technol 76:174–180

Takadoum J, Bennani HH (1997) Influence of substrate roughness and coating thickness on adhesion, friction and wear of TiN films. Surf Coat Technol 96(2–3):272–282

Daure JL, Voisey KT, Shipway PH, Stewart DA (2017) The effect of coating architecture and defects on the corrosion behaviour of a PVD multilayer Inconel 625/Cr coating. Surf Coat Technol 324:403–412

Rosenfeld IL, Danilov IS (1967) Electrochemical aspects of pitting corrosion. Corros Sci 7(3):129–142

Aouina N, Balbaud-Célérier F, Huet F, Joiret S, Perrot H, Rouillard F, Vivier V (2013) Initiation and growth of a single pit on 316L stainless steel: influence of SO 24 − and ClO4 − anions. Electrochim Acta 104:274–281

Turan C, Cora ÖN, Koç M (2012) Contact resistance characteristics of coated metallic bipolar plates for PEM fuel cells–investigations on the effect of manufacturing. Int J Hydrogen Energy 37(23):18187–18204

Jiang R, Wang Y, Wen X, Chen C, Zhao J (2017) Effect of time on the characteristics of passive film formed on stainless steel. Appl Surf Sci 412:214–222

Wang H, Sweikart MA, Turner JA (2003) Stainless steel as bipolar plate material for polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells. J Power Sources 115(2):243–251

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Planning and Budgeting Committee (PBC)/Israel Council for Higher Education (CHE) and Fuel Choice Initiative (Prime Minister Office of Israel), within the framework of “Israel National Research Center for Electrochemical Propulsion (INREP)”, and by the Grand Technion Energy Program (GTEP).

Funding

This study was funded by Fuel Choice Initiative (Prime Minister Office of Israel), within the framework of “Israel National Research Center for Electrochemical Propulsion (INREP)”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stein, T., Ein-Eli, Y. Proton exchange membrane (PEM) fuel cell bipolar plates prepared from a physical vapor deposition (PVD) titanium nitride (TiN) coated AISI416 stainless-steel. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 1420 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1475-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1475-3