Abstract

This article offers insights into the everyday postdigital school life of two schools from two different world regions—Argentina and Germany. Based on ethnographic research in both contexts, it traces the introduction of one educational technology in each case, from the moment of its conception in policy documents to its landing in schools, its appropriation by various school actors and its integration into the socio-technical infrastructure of the classroom. Although both schools are situated differently and both technologies—a learning management system and a tablet computer—are of different quality, the article demonstrates the existence of a remarkable commonality in the journey of both educational technologies: their breakdown and the repair practices performed by various school actors. Breakdown and repair are analysed and conceptualised with reference to the Broken World Thinking exercise. By applying an Ethnography of Global Connections, the locally identified practices in both schools are framed as manifestations of global digitalisation processes in education. The article aims to shift the focus of critical EdTech studies towards two socio-material forces that are commonly addressed separately: material disruption and reassembling (and all the friction in between).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is almost 11 p.m. and Marta—a maths teacher from the city of Buenos Aires (Argentina)—has been sitting in front of her computer for about half an hour. Just as she is about to finish copying her students’ grades from paper to the school system’s platform, her connection crashes. Once again, as the platform doesn’t autosave the grades, her work is lost. She puts down the paper with the handwritten grades and goes to bed. Tomorrow she will try again. Maybe a bit later in the evening, or perhaps early in the morning, when other teachers are still sleeping, she will have better luck.

A few thousand kilometres away, Mr. Krähe—a device administrator of a small school in Lower Saxony (Germany)—sits in front of a pile of 180 brand new iPads. Until recently, the devices he administered were desks, chairs, blackboards, cabinets and various other educational media and objects. Now, with the voluntary help of Julia—a former IT entrepreneur—he attempts to get the tablet computers running. They try to do so once, twice, but they fail. Without a school Wi-Fi connection or any other digital infrastructure, the task becomes tedious, almost impossible. Finally, they come up with a plan and get to work, tackling one device after another in the knowledge that this is going to be a long day.

These two stories, which are based on the narratives shared with us during the fieldwork we carried out for the RED project,Footnote 1 may seem different from each other on many levels to the reader. Nevertheless, they constitute the starting point of our paper because, even if not apparent at first sight, they are closely related through the globally advancing digitalisation of education processes. As the research we will present in this article shows, digital technologies at schools break, stop working, are patched, fixed, discarded and reutilised on a daily basis. Nevertheless, these ‘sticky engagements’ (Tsing 2005) appear to be invisible to the smooth and dominant EdTech policy discourse (Macgilchrist 2021) and its solutionist socio-technical imaginaries (Jasanoff and Kim 2015; Ferrante et al. 2023).

We here address this educational phenomenon by presenting an ethnographic study that analyses the breakdowns and repair practices observed in two schools—one German, the other Argentinian—in light of two recent EdTech policies. The guiding question for our research is: what breakdowns and repair practices can be observed in schooling as part of the sticky engagements that the dominant global EdTech discourse omits? By engaging with this question, we are diving into the day-to-day negotiations involving EdTech at schools and providing an alternative critical framework—a framework that benefits, precisely, from giving analytical salience to the messy, sticky and constantly silenced processes through which schools engage with the global and locally enacted process of digitalisation of education.

We have carried out our enquiry by exploring two theoretical-methodological approaches that complement each other and enable us to tackle the complex and multi-scalar dimensions of our object of study: the Broken World Thinking exercise (Jackson 2014) and the Ethnography of Global Connections approach (Tsing 2005). Broken World Thinking is a research practice rooted in the field of repair studies and Science and Technology Studies (STS) (Harper 1987; Orr 1996; Strebel et al. 2019). It has provided us with both a language and conceptual and semantic tools to perform what we consider an epistemic shift regarding EdTech dominant socio-technical imaginaries and the rhetoric of progress, innovation and inevitability of technological change that permeates EdTech policy (Dussel 2020).

As scholars have observed in the past decades (Selwyn 2010; Macgilchrist, in press), a good part of EdTech introduced in schools promises to enhance students’ learning experiences, making them more engaging and enjoyable. It is expected to alleviate the monotony of traditional teaching methods for educators and guarantee that every student has the opportunity to be involved, participate actively, learn effectively and achieve success. However, a growing body of critical EdTech research consistently indicates a weak correlation between these aspirations and actual educational practices (Dussel and Trujillo Reyes 2018; Macgilchrist 2012; Selwyn 2014).

Our research attempts to elucidate the messy arrangements schools engage with daily as part of the appropriation of digital technologies. By using Broken World Thinking, an exploratory analytical exercise with no prior background in EdTech studies, we aim to shift the focus to two socio-material forces that researchers have commonly addressed separately: material disruption and reassembling (and all the friction involved in the middle). The result of this is the study of a yet mostly unexplored object in the critical EdTech research agenda: breakdowns and repair practices at schools.

Secondly, the Ethnography of Global Connections approach enables us to articulate the situated and practice-oriented Broken World Thinking exercise with larger global processes that impact schools and educational systems. Tsing’s approach not only allows us to address an analytical and methodological gap explicitly identified by proponents of repair studies (Henke 2019; Jackson 2019), but most importantly provides valuable tools and insights for examining the sticky ways in which both localities of our study engage with and shape global phenomena, such as the digitalisation of education.

Finally, this work also seeks to make a first intervention within what we hope will become a larger postdigital dialogue (Jandrić et al. 2019) on the contributions of ethnographic studies and in particular repair studies to educational research on the postdigital condition. In the field of postdigital studies, some critical scholars have strived to align the study of the postdigital with a long-standing tradition in philosophy of technology (Feenberg 1999), which has consistently challenged established assumptions regarding the nature of technology and its interplay with humanity and society. Along these lines, Knox (2019) puts forward two conceptual operations to which our study aims to contribute.

The first such operation assumes that by acknowledging the intertwined nature of the human and the non-human (Latour 1993) the postdigital field offers an opportunity to question the narratives of disruption and novelty that underpin the dominant EdTech agenda. This operation, which we join here, opens up doors to returning ‘to core educational concerns, albeit within the context of a wider society already entangled with, and constituted by, pervasive digital technologies’ (Knox 2019: 361). The second operation is closely linked to postdigital studies’ interest in ‘surfacing the often-hidden material dimensions of the digital such as the human labour required to produce and sustain technology, and the infrastructures and substances required to produce it’ (365). As we understand, this oversight has also contributed to the side-lining of material disruption as part of EdTech studies, a dimension that is crucial to understanding the increasingly digital landscape of schools and also the new conditions, and growing intensification, of teacher work (Selwyn et al. 2017; Bergviken Rensfeldt et al. 2018). By focusing on breakdown and repair, we attempt to offer a first response to this problem.

We have organised our work as follows. In the first section, we introduce the theoretical and methodological guidelines of repair studies. In the second, we provide a detailed background on Broken World Thinking, the exercise that guides our research within the repair studies field. In the third, we elaborate on Ethnography of Global Connections, the approach we have selected to study how localities engage with global digitalisation of education trends. We use the fourth section to present our research findings through a tripartite framework, including the description of policies and schools, the analysis of breakdowns and the examination of repair practices. The fifth and final section serves as both a conclusion and a revisitation of current discussions on the global phenomenon of digitalisation of education, in light of the insights produced by our study.

Literature Review

Breaking, Mending and Creating a Material World: Ethnographic Repair Studies

The ethnographic research we present in this article draws upon the insights of the as yet nascent field of ethnographic repair studies (Strebel et al. 2019). Our literature review indicates that this field has no direct precedents in education, nor in the field of educational technology, and even less so in studies from a critical perspective of EdTech.Footnote 2 However, there are recent studies in the field of education that have adopted the conceptual metaphors of repair studies either as heuristic tools or as a starting point, like in the case of studies on ‘broken data’ (Pink et al. 2018). At the same time, other studies have engaged in discussions regarding the conceptual metaphor of ‘breakdown’, proposing alternatives like ‘noise’ (Macgilchrist 2021) to address, as our work does, the sticky engagements of educational practice. Hence, we consider these studies to be direct antecedents of our research.

While the first conceptual references to bricolage and the notion of repair can already be found in ‘Savage Mind’ by Levi-Strauss (1966), it is during the 1980s and 1990s that we encounter the initial studies focusing on repair not merely as a theoretical concept but as an ethnographic object of interest (Harper 1987; Orr 1996; Henke 1999). These seminal works, which address repair as a situated practice deserving of observation and detailed description, laid the groundwork for a more recent corpus of ethnographic studies. This corpus is authored by a growing and loosely affiliated group of scholars from various disciplines such as sociology, STS, geography and material culture studies (Sormani et al. 2019).

To understand more thoroughly the origin and trajectory of ethnographic repair studies, it is crucial to consider them in light of the broader material turn they are part of (Jackson 2019). Throughout the last century, several philosophers and social scientists have emphasised the valuable insights that instances of material disruption provide for the study of the social. Martin Heidegger’s phenomenological broken hammer allegory (1962) offers an insightful starting point and is a frequent reference in the field: Heidegger suggests that an object only becomes a focus of attention and reflection when it fails to perform its usual function, prompting contemplation of its absence and the disruption of its ‘readiness-to-hand’ (Lynch et al. 1983). However, the issue does not end there: a material breakdown not only highlights problems with the malfunctioning object itself but also brings into question the context of equipment and use. Through disruption, the world makes itself visible.

More recently, Science and Technology Studies have played a crucial role in demonstrating that numerous phenomena traditionally attributed to ‘the social’ are actually deeply intertwined with the material world (Jackson 2019). Therefore, the acknowledgment of the role of things in structuring social experience, coupled with the valorisation of material engagement as a site of human meaning-making and the inseparability of social and material orders, have shaped the principles of studies such as Latour’s work on the missing masses (1992), Barad’s agential realism (2007) and Susan Leigh Star’s research on infrastructures (1999). Within the STS framework, ‘breakdown’ and ‘repair’ have become essential parts of the scholarly vocabulary to discuss technology (Pink et al. 2018), data assemblages or the tasks performed by data scientists and infrastructures (Jackson 2014; Star 1999; Tanweer et al. 2016; Schabacher 2022).

In a similar vein, a growing body of research within the field of material culture studies has underscored the importance of themes such as breakage, decay, repair and displacement. These works focus not only on the mundane yet critical reality of objects consistently being displaced or falling out of order (Domínguez Rubio 2016); they also follow anthropological research lines that have extensively highlighted the processuality of material lives (Appadurai 1988). Many of these studies emphasise that the process of decay is closely intertwined with the processes of creation and development (DeSilvey 2006; Hallam and Ingold 2014). In this regard, Graham and Thrift (2007) argue that maintenance and repair represent a frequently overlooked and missing link in social theory and conceptualise repair as an innovative practice.

This brings us to one of the main traits that distinguish ethnographic repair studies from other STS endeavours: the former focus on material disruption and repair not only as creative and generative phenomena but also, and fundamentally, as part of day-to-day invisible situated practices carried out within systems (Sormani et al. 2019). Here, the importance of maintenance (as a means of keeping systems functioning in their daily existence) and of maintainers (as the keepers of this order) is key. It is precisely for this reason that we have chosen to explore the contributions of this field to develop our study: if the incorporation of EdTech is commonly framed in terms of smooth integration, thereby rendering invisible the friction involved in the processes of digitalisation of education, then the repair studies field provides us with a unique opportunity to explore the generative scope of such friction within the day-to-day practices and negotiations that actors carry out within the socio-technical systems of schools.

Theoretical Concepts

Broken World Thinking: A New Language for an Epistemic Shift

For the purposes of this task, our study adopts a methodological approach with some tradition in repair studies: Broken World Thinking (Jackson 2014). Far from the nostalgic trait its name might suggest, the practice of Broken World Thinking is a creative and exploratory attempt to visualise, analyse and reconceptualise the phenomena that, despite their invisibility, make systems work and continue to function, as in the case of schools. When Jackson defines Broken World Thinking in his foundational essay 'Rethinking Repair', he introduces a core question concerning the life cycles of our world’s machines: ‘what happens when we take erosion, breakdown, and decay, rather than novelty, growth, and progress, as our starting points in thinking through the nature, use, and effects of information technology and new media’ (221)?

In the endeavour to answer this question, the Broken World Thinking exercise organises itself around two ‘forces’ or ‘worlds’ that coexist in the functioning of socio-technical systems: ‘On one hand, a fractal world, a centrifugal world, an always-almost-falling-apart world. On the other, a world in constant process of fixing and reinvention, reconfiguring and reassembling into new combinations and new possibilities…’ (222). The fractal force reflects the fragility of our world, and the recomposing or reassembling force shifts our focus to the often invisible, but always present and ongoing repair activities that consume a significant portion of the time devoted to technologies by the system’s custodians, the maintainers and repair workers who contribute to the stability of socio-technical systems, acting as a counterweight to decomposition.

Just as in other studies that address topics such as breakdown (Alirezabeigi et al. 2020), maintenance (Russell and Vinsel 2019; Schabacher 2020), leakage (Pink et al. 2019) and noise (Macgilchrist, in press), the Broken World Thinking conceptual metaphors present both possibilities and limitations within the semantic terrain they establish. In our case, we are interested in the possibilities these metaphors bring to the table for studying schools as socio-technical systems in their day-to-day functioning. And repair studies and Broken World Thinking, as we will see, are especially productive in this terrain.

Firstly, by accounting for decomposing and recomposing forces, Broken World Thinking synthesises in a single movement two conceptual metaphors that other researchers have addressed separately: breakdown and repair. This is crucial to our study. The conceptualisation of technologies as part of both fragile and constantly maintained socio-technical assemblages highlights some key aspects of the way schools function in scenarios heavily marked by inequalities. Unlike in other research scenarios, in the schools we have studied, breakdown appears as the norm. The fragility of the world, the ruin that prevails in the postdigital condition (Macgilchrist 2021) is a tangible phenomenon. In this materially fragile scenario, the study of repair, hand in hand with breakdown, has been key to bring to light the silenced practices that cope with material disruption concerning EdTech and the complex and creative work that teachers and other school actors perform as maintainers of the socio-technical system.

Secondly, this decision allows us to better understand, from a historical perspective, both the continuity and rupture movements that constitute the production and reproduction of school culture (Julia 1995; Rockwell 2000). Unlike other studies that delve into unexpected breakdown and thus only acknowledge this phenomenon as an entry point (Alirezabeigi et al. 2020), here we would like to consider the historic dimension of schooling and of school assemblages. From this position, in a certain socio-historical context, the phenomena that may occur do not comprehend an infinite scope, but a multiple one. As Henke (2019) articulates regarding repair: ‘This networked complexity of infrastructures means that repair is implied in the very structure of socio-technical systems, and that, when a basic breakdown occurs, structures provide hints at the need for repair and the form that repair will take’ (260). In plain words, in a given socio-historical scenario, not all or infinite possible breakdowns and repair practices may occur. We thus recognise that both breakdowns and repair practices (each on its own, but also together) can be studied, systematised and, to some extent, anticipated and expected—something that, as we will argue more thoroughly in the following sections, could prove valuable for policymaking.

A Globally Connected (and Broken) World

The scenario we face presents several challenges. It is a world where the dominant public EdTech discourses portray the digitalisation of education as frictionless; yet, numerous humanistic studies critically addressing global processes such as surveillance capitalism (Zuboff 2019) leave no room for examining the sticky ways in which the local engages with these processes (Macgilchrist 2021). At the same time, ethnographic studies attempting to account for local friction and negotiations do not always aim to reconnect them with broader processes (Henke 2019; Jackson 2019). In her book Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection (2005), Anna Tsing simultaneously presents a diagnosis, a problem and a path for intervention.

Tsing understands that all human cultures are shaped and transformed in long histories of regional-to-global networks of power, trade and meaning, where universals and particulars converge to create the forms of capitalism with which we live. However, this diagnosis comes along with some epistemological barriers. Defying universalism as it has been dominantly conceived challenges an extended mode of understanding and generating knowledge about the functioning of global phenomena.

Universalism is far from politically neutral—as a close look at the period of European colonial expansion suffices to demonstrate. In this context, the concept of universalism served as the foundation for belief in the expansive potential of reason. This particular form of reason made it possible to unify the dispersed knowledge worldwide, leading to advancements in progress, science and governance. The notion of the universal promised a path towards ever-evolving truths and envisaged an improved existence for humanity on a global scale. Conversely, those colonised were often depicted through the lens of cultural specificity and deemed incapable of evolution and growth (Rufer 2010). These binary schemes and contrasts still organise global asymmetries and can be found in the roots of some of the most widespread conceptions of inequality around the world.

In this scenario, Tsing seeks to intervene through the research of friction: ‘To study engagement requires turning away from formal abstractions to see how universals are used’ (Tsing 2005: 9). In line with our Broken World Thinking approach, Tsing’s proposal focuses on the ‘frictions’ that result from the muddy practical engagement of global processes such as the advancement of capitalism, science, politics or (as in our case) digitalisation of education. ‘We might thus ask about universals not as truths or lies but as sticky engagements’ (6). Macgilchrist (in press) extends this reflection to educational discussions and observes that, from data specialists crafting predictive models to everyday classroom activities, ethnographies challenge the polished portrayals of technology as a flawless, smooth force improving education. In our case, bringing to light the day-to-day breakdowns and the repair practices performed in schools constitutes an attempt to understand the sticky and local production of digitalisation.

Methodology and Material

Schooling in a Connected Broken World

The study we present here is part of a broader research project titled Reconfigurations of Educational In/Equality in a Digital World (RED), which includes research teams from Argentina, Mexico, Germany, Sweden and South Africa. Carried out between 2020 and 2024, the project aims to study the reconfigurations of schooling through the processes of digitalisation of education in different regions of the world and the ways in which these reconfigurations reproduce inequalities or improve conditions of equality.

In Argentina, the project involved fieldwork in four schools in the city of Buenos Aires—three public and one private. This paper presents findings from one of the public schools, La Escuela de la Avenida.Footnote 3 The fieldwork at this school was conducted between November 2022 and May 2023. Within the framework of participant observation, the research included conducting semi-structured and unstructured (ethnographic) interviews with school administrators, teachers and pedagogical-digital referents, observing and recording classes from a 3rd-year course (14–15 years old) and documenting participant observation activities in field notebooks throughout the process.

In Germany, the project involved fieldwork in three schools, all public urban schools located in the federal state of Lower Saxony—one Gymnasium (an academically oriented school), one Gesamtschule (mixed student clientele) and one Hauptschule (practically oriented school). This paper presents findings from the Hauptschule, here named the Vogelsangschule. The fieldwork at this school was conducted between February 2022 and December 2022. This involved participant observation of a grade 8/9 classroom (13–16 years old), conducting semi-structured interviews with teachers, school leaders and school administrators as well as holding unstructured (ethnographic) interviews with various actors in the field.

In both cases, we also conducted an analysis of policy documents. This allowed us to achieve a more precise understanding of the discursive and techno-pedagogical framing of the policies designed to regulate the use of the digital technologies we aimed to track at schools. Additionally, it enabled us to have a closer look at how these policies framed a phenomenon that, according to specialised critical EdTech literature, is global in the EdTech field: the omission or smoothening of friction.

The selection of these two schools for our Broken World Thinking exercise emerged from an ongoing dialogue between the two authors of this article and, more specifically, from the recognition of a coincidence that initially struck us as noteworthy. During our fieldwork, these two schools very clearly exhibited the two forces that make up the Broken World Thinking analytic model: decomposition and recomposition. This refers not only to the friction that, although often omitted or smoothened in EdTech discourses, continually surfaced in each school’s attempt to incorporate digital technologies, but also to the more generative and equally omitted aspects that allow the schools to continue functioning in spite of that friction. This double omission, which mirrored the Broken World Thinking focus, constituted the starting point of our work and first hinted at what we later conceptualised as a global phenomenon.

In the case of the Argentinian school, one of the triggering signs was the successive interruptions that occurred during one of the semi-structured interviews conducted as part of the stay at the school and carried out with the techno-pedagogical coordinator, who is responsible for implementing the digital education curriculum of the jurisdiction's educational policy. Most of these interruptions were related to unlocking computers, solving technical problems and answering technical questions about software use that other school actors could not resolve. As the Argentinian researcher later learned, a large part of the techno-pedagogical coordinator’s work consisted of solving these problems—an aspect completely neglected in Buenos Aires’s curricular policy, which focuses on the acquisition of twenty-first-century digital literacies. This constant ‘firefighting’, as the teacher described it, caused tensions between her competing roles: the Education Ministry’s demand that she works with a new curriculum collided with the duties and practices the school assigned her, which involved (as we later phrased it) the repairing of breakdowns.

This case resonated strongly with an observation from the German school, where a teacher was conducting a physics lesson. Her expertise in this subject was very limited, as she normally taught subjects from the humanities. However, the school’s lack of personnel forced her to substitute teach. In order to still provide her students with high-quality lessons, she started by showing explanatory videos from trained physics teachers via the streaming platform YouTube. This was surprising, as the school does not have a functioning Internet connection. It turned out that the teacher had bought a premium account on YouTube, which enabled her to save videos offline and play them without a connection. In this practice—of a teacher investing personal financial and time resources to keep the school running and to fulfil the political call for digital education—we also saw fractures and tensions between a frictionless policy discourse and a messy school reality. We would later reframe these practices in the context of breakdown and repair and interpret them as global phenomena.

We begin our analysis by describing the German and Argentinian schools, given that they constitute the socio-technical systems where the educational technologies we follow are assembled, and also the educational policies that orient the inscription of these technologies within both schools. Afterwards, and given that the universal is enacted in the ‘sticky materiality of practical encounters’ (Tsing 2005), we describe and systematise the way each educational technology interacts with human and non-human actors within each school’s socio-technical assemblage—something similar to what in STS and ANT has been called ‘translation’ (Callon 1984). Here, we focus on the silenced breakdowns and repair practices that produce the global process of digitalisation of education in each scenario. The material presented here can be described as ethnographic reports from the two case studies. We generated it by using ethnographic field notes to create thick descriptions of school practices. In order to tailor these descriptions towards this paper’s comparative aim and to not overextend its scope, we distilled short narratives from the descriptions and arranged them in a dialogic form between both cases. Although this approach does remove some of the ethnographic description’s thickness, it enables us to give a more condensed presentation of our findings.

On the Argentinian side, we follow a hybrid platform called MiEscuela, a LMS with school management functionalities; on the German side, we follow a tablet computer known as an iPad that is used as a learning device. Since our descriptions each follow a specific technology, it could be assumed that our analysis is aimed at the individual functioning of these technologies. However, we emphasise that we only adopt this perspective in order to trace the embedding of the technologies in more complex systems, associated to practices and actors. We are thereby aiming at an analysis of socio-technical school systems in what we understand is a broken and connected world. This means that digital technology engagements in each context present interesting insights not only on how digitalisation of education is produced in local scenarios, but also on the sticky interplay between the global trends and local negotiations and practices.

Finally, our analysis works not only in a vertical, but also in a horizontal way. In spite of the differences concerning context, policy and digital technologies, the operation of contrasting both localities has helped us to understand each locality more thoroughly in its complexity (Marcus 2001). This comparative operation has allowed us to perceive not only differences but surprising similarities and patterns in how the schools deal with digitalisation of education. As we will demonstrate in the discussion sections, these similarities reveal some of the most pressing challenges involved in the digitalisation of education and schooling.

Localities and Policies

Vogelsangschule and the Sofortausstattungsprogramm

Vogelsangschule is a secondary school in an urban area of the federal state of Lower Saxony in Germany. In the traditional three-tier German school system, the school is considered part of the Hauptschulen—schools attended by students who are aiming for vocational training in hands-on professions. The school is therefore more practically than academically oriented. Vogelsangschule operates in a relatively precarious setting, reflected in aspects such as a building requiring renovation, a lack of digital infrastructure and a notorious staff shortage. The majority of students come from low-income families, and around 90% have learnt or are currently learning German as a foreign language.

The arrival of the tablets in Vogelsangschule becomes understandable within the context of the so-called Sofortausstattungsprogramm (Immediate Equipment Programme for Digitally Supported Teaching), a policy the German government adopted in March 2020 as a result of an extension of the so-called DigitalPakt Schule (BMBF 2019) during the Covid-19 pandemic. This initiative thus ties back to the broader trajectory of the DigitalPakt Schule. In 2012, the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs (KMK) aimed to firmly embed media education within school education through the declaration Media Education in Schools. However, the nationwide implementation of this declaration was slow. The pace only quickened with the introduction of two pivotal policy strategies: the Education in the Digital World strategy in 2016, which underscored the importance of digital competence across school curricula, and the DigitalPakt Schule, launched in 2019. The latter provided the Länder with a special fund of 500 million euros specifically for the purpose of enhancing digital infrastructures and supporting the acquisition of digital technologies in schools.

This fund enabled schools and school authorities to purchase digital devices and lend them to students specifically ‘to compensate for social imbalances’ (BMBF 2020: 1). Policymakers split the 500 million euros between schools using a social index on the federal level. In Lower Saxony, federal authorities using this ‘social index’—which included various social welfare indicators such as unemployment benefits or asylum benefits—calculated that an average of 14.7% of students would be entitled to borrow one of the purchased devices. However, after the local school authority applied the index to Vogelsangschule, it awarded the school 180 devices for its 320 students, corresponding to a share of 56.3%. The devices purchased by the school authority were iPads by Apple—a company that had already aggressively positioned itself in the education market with its products and services before the Covid-19 pandemic (GEW 2019).

Escuela de la Avenida and the MiEscuela Platform

Escuela de la Avenida is a state-managed, traditional secondary school situated in a wealthy neighbourhood of Buenos Aires, the capital city of Argentina. With a history spanning over a hundred years, this institution serves approximately 800 students divided across two shifts: one in the morning and the other in the afternoon. Focusing on Natural Sciences and Social Sciences and Humanities, it caters for a student body whose socioeconomic background predominantly ranges from lower to lower-middle sectors. Despite its location in an affluent area, a significant portion of the students commute from more peripheral parts of the city, many being children of workers employed in the neighbourhood during the day.

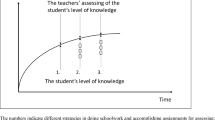

MiEscuela is the digital platform that Escuela de la Avenida, as well as the rest of the city’s secondary schools, massively adopted in the year 2018. The platform was launched as part of the Secundaria del Futuro (Secondary of the Future), an educational policy aimed at adapting secondary education to embrace the latest technological innovations and thus arm students with relevant skills and knowledge for the digital age. In the frame of this modernisation trend, policymakers presented MiEscuela as a platform that would help school staff, and mainly teachers, streamline and unify various processes: the creation of virtual classrooms through the integration of Google Classroom; the organisation and planification of classes and online work with groups; the tracking of tasks, attendance, grades and progress of each student. This platformisation process would also positively impact on the communication between schools and families and would translate into a modernisation of the school system.

Far from the launching announcements, the platform’s most frequent use in the present is to register evaluations and attendance. Bi-monthly, teachers are required to register and submit student grades via MiEscuela. While teachers are responsible for inputting grades for their respective courses, the school secretary aggregates this data to produce a comprehensive report card that includes all subject grades, attendance and disciplinary records if applicable. Although families have access to the platform, interviews with school staff suggest that they use this resource only infrequently, due to limited Internet connection and lack of digital skills. The school thus also gathers the platform data into a complementary printed report card it sends home to families. In September 2022, the city’s Ministry of Education responded to these problems by launching an app for families, so that they could access attendance and evaluation information related to the students and also communications from the school. Nevertheless, printed report cards remain the main communication means between many schools and families.

Discussion: The Policy’s Techno-Pedagogical Orientations

In the case of our study, three educational policy frameworks guide the techno-pedagogical orientation of the specific policies of the schools we have depicted. In the German case, we have the Education in the Digital World strategy, launched in 2016, which identified digital competence as a core task to be integrated into all Länder school curricula. Secondly, the DigitalPakt Schule policy, introduced in 2019, also followed a digital competence framework and provided Länder with a 500-million-euro fund to develop digital infrastructures and acquire digital technologies for schools. Both policies highlight Germany's perceived delay in digitalisation compared to international standards and address concerns about insufficient teacher training, a lack of federal and state cooperation and inadequate funding.

The MiEscuela platform is part of a broader educational policy, Secundaria del Futuro (Secondary School of the Future), an initiative launched in 2017, that aims to deeply reshape and modernise secondary education in the city of Buenos Aires through the integration of digital technologies. As outlined in its policy documents, Secondary School of the Future is not just a curriculum reform but a shift in the educational paradigm of the jurisdiction, where digital technologies are integral to schooling reconfiguration. The secondary education envisioned by this policy is dynamic, adaptive to technological advancements and future societal needs, updating teaching methods and learning to reflect the realities of contemporary adolescents and XXI century’s labour demands.

Despite the differences these policies may show, we have detected two common patterns that bring them together and also align them with the policies analysed in prior literature on socio-technical imaginaries (Ferrante et al. 2023; Büchner et al. 2023). The first one is the shared solutionist (Morozov 2013) orientation of the three policies’ documents. There, heavily anchored in the myth of digital universalism (Chan 2014), technology constitutes a promise, a panacea to solve complex problems that have to do with a wide range of challenges: teachers’ work, teaching practices, learning, the challenges of a changing labour market and citizenship, among others. The second pattern is that these policies manifest an evident silence (Bacchi 2012) when it comes to the sticky engagements involved in school staff’s daily work, the practices concerning digital technologies and the ways these relate to existing school practices. None of the phenomena we describe from now on can be inferred from reading policy documents. None of them are foreseen at some scale nor addressed under the smooth discourse of EdTech either. They bluntly fall under the radar.

Theme A: Breakdowns at School

In this section, we address the decomposing forces of our Broken World Thinking exercise and present the breakdowns observed during our fieldwork in both schools, along with the insights that result from the comparison of these localities. Like previous studies on breakdown (Alirezabeigi et al. 2020), our analysis tries to unveil the silenced making of digitalisation in day-to-day schooling and focuses on the ways in which these new technologies interact with the functioning of school as a socio-technical system. As we have already established, within repair studies, breakdowns do not only imply the mundane breakage of an element or object, human or non-human, but also a disruption in a system, with its assemblage and the practices that make it possible.

Breakdowns at Vogelsangschule

The first form of breakdown that we have found in Vogelsangschule involves school staff’s knowledge and availability concerning the setup of digital technology. The 180 iPads need initial setup for use. This requires a minimum of technical expertise and personnel. At Vogelsangschule, neither was available at the time the devices landed. On the one hand, the school (like most of the German school system) has a staff shortage—the available personnel are needed to cope with the normal school routine, making them unavailable for device administration. On the other hand, there is also limited technical expertise at the school. The position of media officer, which has been required by school law since 2016, is occupied by a teacher who is prevented from working for an indefinite period of time due to health reasons—a situation that is also created by the systemic lack of staff and the teachers’ high workloads.

The second form of breakdown also concerns the setup of digital technology, but this time linked to parents’ schooling practices. Setting up the iPads requires the creation of an Apple ID. However, this personalisation of the devices can only be done by users of legal age, which in the school context would be the students’ parents. Yet parent contact has traditionally been a complicated endeavour at Vogelsangschule. For example, a large proportion of parents do not speak German and cannot be contacted by the school, despite extensive translation measures. In addition, Vogelsangschule educates many students from family contexts in which formal schooling does not play a major role. Here, many parents do not see themselves as dialogue partners of the school and withdraw from communication. In addition, many students attending Vogelsangschule do not live with their parents, for various reasons. All of this means that setting up identification poses major challenges.

The third form of breakdown involves school infrastructure and the management of digital technology. Vogelsangschule’s infrastructure is not prepared to manage 180 devices. The school, which has long been in need of renovation, has only one storage chamber for equipment. There are not enough power outlets to properly store the iPads, and the chamber is occupied by a set of laptops that were purchased several years ago and are not in use.

The fourth form of breakdown also concerns school infrastructure, although this time specifically linked to digital technology interoperation. Part of the school’s need for renovation is also the lack of connection to the Internet (Wi-Fi) and lack of digital equipment, such as digital display technologies (i.e. interactive boards or projectors). Therefore, the iPad can interoperate only poorly in this environment and loses a large part of its potential function as a teaching and learning medium.

The fifth and last form of breakdown detected in Vogelsangschule responds to schooling practices and the way they relate to digital technology policy. Due to the specific student clientele at Vogelsangschule, many of the everyday schooling practices are designed for physical presence at school. Because of the students’ often precarious home situations, educational materials are not brought to school, but kept on site. Similarly, the school offers breakfast to compensate for the deprivation many students face at home. The idea is to remove as many organisational barriers as possible for the students so that they only need to (physically) come to school and not have to worry about much else. The policy idea of the iPads, however, is to provide students with devices on a one-to-one basis, which they then take responsibility for (at school and at home). This idea is in direct conflict with the established place-based schooling practices and further complicates everyday school life for students and teachers.

Breakdowns at Escuela de la Avenida

In Escuela de la Avenida, we detected a first form of breakdown involving school staff practices. In some cases, these practices find a limit and challenge in digital technology’s affordances. Teachers have to upload grades and evaluations to MiEscuela at the end of each bimester. They frequently perform this task some days before the deadline. With so many grades being uploaded simultaneously and platform use intensifying, MiEscuela overloads and crashes, thus interrupting teachers’ work. Complaints about platform malfunction accordingly rise during these periods, yet the problem persists.

We detected a second form of breakdown involving school staff's available infrastructure and the way it connects to digital technology's affordances. The MiEscuela platform does not possess an autosave function, and the teachers’ and preceptors’ Internet connections (mainly at home where they perform this task, but also at school) are unstable. It is therefore very common for the Internet to crash and teachers to be forced to carry out their work more than once. This work overload is not an isolated phenomenon: teachers across different jurisdictions of the Argentinian educational system complain about the bureaucracy involved in the recursive register of grades across different media.

The third form of breakdown responds to school staff practices and the way they speak to digital technology updates. Ever since launching MiEscuela, the ministry’s administration has been modifying and updating the platform—and it has done so without consulting school staff or communicating the approaching changes. This has happened not only with the grading categories that teachers assign students to pass from one year to the following, but also with other platform functionalities involved in their work. Before the pandemic, for example, some teachers used the platform’s planification form to upload the school year’s activities. They treated it as a rubric for following up on their own work and checking if they had accomplished the goals set for the year. After the pandemic, the administration removed this planification functionality without consulting teachers or communicating the change.

This takes us to another form of breakdown, also linked to communication issues, this time involving parents’ schooling practices and the use of digital technology. Even though MiEscuela was launched in 2018, the platform has still not penetrated as a channel of communication between families and schools. In other words, it has failed to fulfil one of the main objectives that inspired policymakers to create it in the first place, in a modernising spirit. In many schools, including Escuela de la Avenida, parents do not access student evaluations through MiEscuela, nor can teachers or schools communicate with them through the platform.

The last form of breakdown we have observed differs from the previous ones, as it responds to digital technology’s inherent fails. This means that it not only involves the encounters and negotiations between the school’s socio-technical assemblage and the educational digital platform, but it is part of an inherent malfunction of the digital technology. We have found two examples of this. The first involves the MiEscuela platform losing teachers’ registered grades—that is, the grades disappear from the system record after uploading, as school staff have stated. Secondly, the MiEscuela platform crashes in random moments, even when it is not overloaded with activity, as happens at the end of each term. This is a problem that crosses all of the practices that involve the use of the platform.

Discussion: Breakdowns

The first thing we can observe is that these mundane breakdowns may stem from an object breaking, like in the case of inherent failures from digital technology in the Argentinian school, but it can also be the result of a frictional pairing—a lack of fit between the infrastructure, knowledge and practices that digital technologies and the school’s socio-technical system demand from each other. In other words, a breakdown may occur in two different forms:

-

1.

Technical functionality failure: This breakdown takes place at the level of the technical functionality of the technology itself. In this case, the technology is attributed functionalities that it does not or cannot fulfil, contrary to its ideal design. Although the school context surrounding the technology would have allowed it, the practices associated with the anticipated functionalities cannot be carried out, or only against great odds.

-

2.

Contextual pairing failure: On the other hand, breakdowns occur at the level of school contextual functionality. Although nothing stands in the way of the technical functionality, school contexts such as the infrastructure, work routines or cultural aspects ensure that the practices associated with the technology’s anticipated functionality cannot be carried out, or only against great odds. It is precisely at this level that we find similarities between the two schools. Although the schools differ as radically in their situatedness as the technologies differ in their characteristics, the breakdowns exhibit clear similarities. The teachers’ heavy workload and the precariousness of the teaching profession should be mentioned here. While these working conditions make it difficult to integrate the technologies into the school’s existing socio-technical system, at the same time, they are further exacerbated by the technologies’ logics and requirements. We also see that the integration of technologies is reconfiguring the role of parents in the socio-technical system. In this context, parents and guardians are envisioned as actors with specific roles—for example, as communication partners or device administrators. In our study, however, parents at neither school were able to fully take on these roles. They were less involved in school life, did not speak the language, could not operate the technology or were excluded from communication due to technical malfunctions.

In this very close-to-practice level of analysis, we do not intend to attribute responsibility for breakdowns to any human or non-human actor. Instead, we try to conceptualise breakdown as a failed encounter and also as the beginning of a series of practices meant to reestablish and renegotiate the lost order (Henke 2019). In light of this, we would also like to add that the more frequently used term ‘clash’, which points to the encounter between agonistic forces, may not be accurate when it comes to describing processes that have more to do with objects and systems interacting. In these encounters, the interacting elements demand from each other things they do not possess and envision each other in terms that diverge from what they actually are. More importantly, these encounters usually do not end with the rejection, explosion or destruction of the parties involved, but rather with the demand that elements be repaired or reassembled in new ways, so that people and institutions may continue working and functioning. This also leads us to another core argument of our work, which we will further develop in the following sections. We have observed that when we focus on the reassembling force that puts back the pieces of the broken order, agency necessarily needs to be reframed: those in charge of making things work after breakdown are not the policy designers, but the workers who keep school functioning day after day. The use of the term ‘clash’ may not be suitable to provide salience to this already frequently neglected phenomenon.

Theme B: Repair Practices at School

In this section, we address the recomposing forces of our Broken World Thinking exercise—the silenced repair practices in which school staff engage in order to generatively mend the system, negotiate breakdown and keep the schools working. As we have already commented, we are presenting an ‘expanded’ definition of our object (Henke 2019), according to which repair is not just a fixing practice nor carried out only by those who are commonly understood as repair workers, like plumbers, electricians or tailors. Repair, as we conceive it, is part of the fabric of everyday interactions, given that it constitutes a practice for negotiating order and stability between people, organisations and materiality in scenarios where, as in the case of the schools we have studied, heterogeneous objects come together and give life to complex socio-technical systems.

Repair Practices at Vogelsangschule

The first repair practice observed in Vogelsangschule falls under what we have categorised as interinstitutional cooperation. Even before receiving its 180 new iPads, Vogelsangschule had been struggling to maintain its technological devices. Operating the long-established computer classroom also repeatedly requires technical expertise which the school’s personnel cannot provide. For some time, the school has therefore been cooperating with the city’s volunteer centre, which is run by a non-profit organisation and financed by donations. People and institutions from the city can submit both requests for help and offers of help to the volunteer centre. Vogelsangschule previously asked the centre for help with the maintenance of its technical school devices. The centre established a cooperation with the Nohl couple—former IT entrepreneurs who were interested in civic engagement after selling their company. After receiving the 180 iPads, the school’s device administrator Mr. Krähe contacted Julia Nohl again to set up the devices. Despite the socio-technical breakdowns described above, they together managed to get 30 of the 180 devices running. These were given to individual students for purposes such as solving maths problems or learning vocabulary at home via learning apps. The other 150 were stored for the time being in a small storage room, next to an old and dusty set of laptops that the school acquired some years ago.

Another repair practice that we observed was the use of backup/alternative technology. The use of iPads at Vogelsangschule during the time of school closure and distance education was sporadic and unsatisfactory. Teachers began to resist the technology and develop their own teaching strategies, which they deemed more suitable for the individual student clientele at that time and in that context. The most successful approach was the open-window strategy: once a week, students were expected to come to the (officially closed) school and pick up educational materials in the form of printed worksheets. To do this, a large window of the school was opened towards the street side, allowing students to access the materials without entering the school, which was then prohibited. Although this strategy also did not reach all students, teachers judged it to be significantly more promising than the iPad, because it tied into the forms and habits of the pre-pandemic school day. It provided students with orientation, comfort and structure. School actors resisted the iPad and replaced it with another technology: that of the open window and the printed worksheet.

The last repair practice observed in Vogelsangschule is the repurposing of technology, linked in this case to interinstitutional cooperation practices. A few months after the end of the school closure depicted in the previous paragraph—when Germany’s schools had reopened and the 180 iPads were accordingly no longer in use—another global phenomenon enters Vogelsangschule’s everyday school life. The war in Ukraine has caused countless Ukrainian families to flee, many coming to Germany, and Vogelsangschule is traditionally the district’s school that accepts as many refugee children as possible. Compared to their new classmates, the Ukrainian children often come from family contexts where digital technologies are a well-established part of everyday life. In addition, their old schools in Ukraine and teachers who stayed behind often offer digital distance teaching. The 30 iPads Mr. Krähe and Julia Nohl had set up so many months previously are now finding a new purpose by being lent to the Ukrainian students so they can participate in distance learning. In addition, the local school authority has asked the Vogelsangschule to return the remaining 150 iPads so that they can be redistributed centrally to other schools with Ukrainian students. This was agreed to and the journey of the iPads at Vogelsangschule has come to an end, through a repurposing of the technologies and a reinterpretation of the policy idea that made them appear in the first place.

Repair Practices at Escuela de la Avenida

As already mentioned, one of the main and most problematic practices teachers have been carrying out on the MiEscuela platform since its 2018 launch is grade registry. The first repair practice found in this school thus responds to this form of breakdown and concerns the use of backup/alternative technology. Given the platform’s inherent failures and breakdowns, teachers do not trust it when uploading and saving their students’ grades. Accordingly, some have started keeping a double record of these data. First, they register and save the grades in more liable supports, both digital and printed; only then do they make a second (and frequently problematic) record by uploading them to the digital platform. This practice of recording grades by hand on paper and in some cases a second time on an Excel spreadsheet is common among the school staff. Yet even if this double record-keeping is a frequent practice, we cannot affirm it has become naturalised. Instead, part of the school staff openly criticises it for intensifying teacher work.

The second repair practice detected in Escuela de la Avenida is close to the first one, as it also involves the use of backup/alternative technology. Teachers have supplemented their double record-keeping with another adjunct practice in reaction to, and as a form of negotiation with, MiEscuela’s failures and breakdowns. Since, as we have seen, the platform loses grades after they are uploaded, teachers sometimes opt to download their just-entered spreadsheets, keeping them as both a digital record of their work and as evidence, should a problem related to these records arise in the future.

The third repair practice observed acts as a response to the platform collapsing when its use intensifies. In this case, there is an alternative use of the digital technology. Some teachers avoid using the platform during massive simultaneous use and opt to perform their grade uploading practices at other moments of the day, when the platform is more likely to work properly. These suitable moments may vary, but they are usually late at night or early in the morning. Sometimes teachers even share information on the optimum moments for platform use with colleagues who have also experienced platform crushes. There is another practice similar to this one: conducting the final evaluations of each period some days before the respective grades must be uploaded to the platform at the end of the bimester. By slightly anticipating the moments when the grade uploading practice has to be performed, teachers avoid the platform crush breakdown.

The last repair practice detected in Escuela de la Avenida is the use of a backup/alternative technology that acts as an answer to communication-related breakdowns. Since many families from the community do not use the platform as a communication channel, Escuela de la Avenida authorities have opted to use a more traditional and settled means of communication, one that has proven more effective than the platform: printing and circulating report cards among students’ families, just like other public schools in the city of Buenos Aires. It is worth noticing that this repair practice creates what we consider a new crack in the system: although MiEscuela does not limit the word count of a teacher’s conceptual evaluation, printed bulletins do. This has forced teachers to adjust the length of their conceptual evaluations in the platform to later fit on the printed, space-restricted paper evaluations. In this way, the breakdown indirectly models the length and therefore the form of the teacher’s conceptual evaluation.

Discussion: Repair

In both contexts, teachers and other school actors respond to everyday school breakdowns with constant repair efforts. As discussed in the previous section, the breakdown is to be seen as a socio-technical phenomenon that takes place in the interplay of many components of the school infrastructure. Accordingly, repairing, as we want to discuss here, is also a socio-technical phenomenon that does not only and not always unfold as a technological fix. Nevertheless, it always works at the socio-technical level. This allows us to emphasise the idea of repairing as re-pairing: the creative and innovative drawing of connections between components of a socio-technical system. In this sense, re-pairing is the finding of pairs, the reassembling or recomposing of objects, actors, institutions, ideas or affects to cope with a day-to-day school life that is characterised by breakdown.

Taking a step further in our analysis, we have formalised five classes or forms of repair that account for the complexity of this silenced practice that is performed by school staff.

-

1.

Repairing-as-Anticipating: This form of repair is a result of school staff anticipating breakdowns. Here, these breakdowns render themselves iterative on the level of practice and repairing is fruit of the institutionalisation of a certain assemblage of human and non-human actors that prevents a breakdown from happening before it even materialises, given that it is foreseeable. Yet the fact that these practices become regular does not necessarily mean that school staff accept them, as they in many cases resist the accompanying work intensification. We can locate these repair practices, for example, in cases 1, 2 and 3 from the Argentinian school.

-

2.

Repairing-as-Partnering: In this particular form of repair, school actors partner or pair themselves with new actors to modify technologies that do not fit with or break in the existing school socio-technical assemblage. These practices include collaboration with new actors within the school or in other institutions. They may involve changes in the composition of the school’s socio-technical infrastructure, negotiations about the involved parties’ needs and demands as well as an exchange of knowledge between school and external actors. We can locate these repair practices, for example, in cases 1 and 3 from the German school.

-

3.

Repairing-as-Remodelling/Repurposing: This form of repair can take various forms. It occurs when school or external actors modify or repurpose a technology new to the school so that it may function properly within the school’s socio-technical system. The remodelling practice can simultaneously draw upon technical knowledge about the new technology and knowledge related to the school’s socio-technical system and how the new technology can adapt to it. As seen in case 1 of the German school, this knowledge can be negotiated between school actors and external actors. It also occurs when a human or non-human actor traditional in school is modified to adapt to a new technology, as observed, for example, in cases 1, 2, and 3 from the Argentinian school. Moreover, the first and second situations can (and frequently do) occur simultaneously.

-

4.

Repairing-as-Replacing/Complementing: When a technology does not fit the school’s assemblage and cannot be fixed or changed in order to fulfil its purpose within the socio-technical system, other actors find a replacement or a complement. In some cases, they meet new tasks by repurposing old technologies, like windows in case 2 from the German school or report cards in case 4 from the Argentinian school. This sometimes leads to what we call ‘reverse retrofitting’. Within engineering studies, retrofitting is the process of updating older systems by adding new technology or features to modernise them and enable them to perform tasks for which they were not initially designed. What we observe in our cases can be understood as reverse retrofitting: the process of complementing newer technologies with older ones that prove more suitable or adequate for practice.

-

5.

Repairing-as-Discarding: This form of repair occurs when a new technology is discarded because it does not fit into the socio-technical system where it has landed. In that case, the lack of fit and the resulting friction are resolved by discarding the new technologies. These rejected technologies may either be put into storage, or they may continue their journey in other localities where they can be used, remodelled or repurposed—as the final destination of the iPad’s trajectory in the German case.

This set of practices is closely intertwined with other school practices, with which they maintain different types of relationships. If teaching and learning are core practices necessary for the system’s functioning, breakdown and repair at school will necessarily articulate with them: as we have seen, teachers may replace technologies as a form of resistance to the pedagogical practices linked to them; alternatively, they may choose to use them as they fit new educational practices. A platform may contribute to modify the way teachers evaluate and communicate evaluations. What is important to us is that, although these articulations between pedagogy and EdTech are multiple, and deserve to be studied in detail, there is a significant pattern that crosses them and summons our attention. This pattern becomes clearer when we frame the relationship between EdTech and schooling in terms of breakdown and repair, that is, in less discreet and more processual terms (Appadurai 1988). When breakdown occurs, the responsibility and workload of re-pairing the system lay with the people who work in schools. Keeping the system functioning involves time, effort, the acquisition of new knowledge and the development of negotiations that exceed school staff’s already intensified (and normally uncompensated) work. This also means that by not contemplating the sticky engagements involved in the incorporation of digital technologies in schools, educational policymakers are not only failing to anticipate the problems they are attempting to address, but are also generating new breakdowns that are then left for school actors to repair.

Closing Remarks: Possibilities and Restraints in Concept Metaphors

In this closing section, we would like to take this line of thought a step further and reframe human agency within our work. When it comes to responsibility and workload, human and non-human agencies are not comparable, even if rendering their connections visible is analytically productive, as we argue here, and allows us to discuss those approaches that smoothen the disruptive role of technology at school or simply frame it in terms of clashes. As the sociologist Bram Büscher explains when reflecting upon recent critiques to the non-human turn, ‘this is not a call for unbridled human supremacy or to depreciate attention for the nonhuman. It is about making political distinctions as to when and where it is exclusively up to humans to make or resist particular choices within contexts that are always already entangled with nonhumans’ (Büscher 2022: 69).

As we have seen, school staff are in charge of repairing a wide range of the systems breakdowns policymakers’ flawed projections create. In this regard, and as a summary of our Broken World Thinking exercise, we have here revealed the existence of various breakdowns and repair practices that act as forces of decomposition and recomposition within the socio-technical system. Furthermore, we have observed—in an as yet not finalised, open and exploratory manner—that these breakdowns and repair practices can be organised into two major forms for the first case (Technical Functionality Failure and Contextual Pairing Failure) and five for the second (Repairing-as-Anticipating, Repairing-as-Partnering, Repairing-as-Remodelling/Repurposing, Repairing-as-Replacing/Complementing and Repairing-as-Discarding).

We have demonstrated that the global process of the digitalisation of education is being projected and advanced at a double expense: intensifying the work of those who maintain the daily functioning of school, as well as silencing the generative knowledge and practices these actors produce. School staff continuously develop contextualised, practice-based and often understudied knowledge on how to manage friction as part of their daily work. This knowledge is crucial for understanding EdTech appropriation in schools as part of a re-pairing process, where innovation involves not only the introduction of the ‘new’ but, more importantly, the messy (re)arrangement of existing pedagogical practices, teachers’ work and objects to keep the system functioning. By engaging in a Broken World Thinking exercise, we have not only explored the possibilities of an epistemological shift that unveils these issues but also attempted to confront the dominant research lines that inform policymaking and EdTech discourse with the day-to-day challenges faced by school actors in their educational practice, which are often omitted.

Finally, our study aims to call for the recentring of the agency of public, private and third sector actors involved in the design of EdTech policies. Just as there is a risk in romanticising maintenance and repair (Mattern 2018), there is also one in essentialising breakdowns. We understand that contrary to what some repair studies suggest, breakdown can never occur solely due to the passing of time or the force of natural material decay and erosion. A broader political and socio-historical view makes clear that not intervening when breakdowns occur is also a form of active intervention that deepens inequalities and impacts teachers’ work. In this sense, our Global Connections framework allows us not only to observe the policy imaginaries that contribute to this lack of intervention and silencing, but also to reframe agency on a global scale and project new concept metaphors that provide political salience to the responsibility of actors involved in the advancement of the digitalisation of education. As a closing remark, and in order to avoid essentialisations in the use of concept metaphors, we would therefore like to put forward and open to further analysis the following idea: although ‘breakdown’ is a productive term on one level, on another, given its formal and semantic composition, it may render unspecific the agency that causes it. This is why, in the context of analysing global connections, we believe that practices should be reframed in more agentic terms. Based on the scenarios we have depicted, we accordingly find that the concept metaphors of ‘sabotage’ or ‘programmed obsolescence’ could be fruitful for future ethnographic and critical interventions addressing breakdown and repair in their global connections and political responsibilities.

Notes

RED (Reconfigurations of Educational In/Equality in a Digital World) is an international research project including research from Argentina, Germany, Mexico, Sweden and South Africa. It seeks to study in/equalities in digital education settings by including and combining policy, practices and infrastructural studies.

For this reason, we will take a brief detour and outline the theoretical and methodological foundations that organise it.

All names included in this article referencing schools and school actors are pseudonyms.

References

Alirezabeigi, S., Masschelein, J., & Decuypere, M. (2020). Investigating Digital Doings Through Breakdowns: A Sociomaterial Ethnography of a Bring Your Own Device School. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(2), 193–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1727501.

Appadurai, A. (1988). The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (Reprint Edition). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bacchi C. (2012). Introducing the ‘What’s the Problem Represented to be?’ Approach. In A. Bletsas & C. Beasley (Eds.), Engaging with Carol Bacchi: Strategic Interventions and Exchanges (pp. 21–24). Adelaide: University of Adelaide Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/UPO9780987171856.003.

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

Bergviken Rensfeldt, A., Hillman, T., & Selwyn, N. (2018). Teachers ‘Liking’ Their Work? Exploring the Realities of Teacher Facebook Groups. British Educational Research Journal, 44(2), 230–250. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3325.

BMBF–Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung. (2019). Verwaltungsvereinbarung. DigitalPakt Schule 2019 bis 2024. https://www.digitalpaktschule.de/files/VV_DigitalPaktSchule_Web.pdf. Accessed 24 June 2024.

BMBF–Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung. (2020). Zusatz zur Verwaltungsvereinbarung DigitalPakt Schule 2019 bis 2024 („Sofortausstattungsprogramm“). https://www.digitalpaktschule.de/files/Zusatzvereinbarung-web.pdf. Accessed 24 June 2024.

Büchner, F., Bittner, M., & Macgilchrist, F. (2023). Imaginationen von Ungleichheit im Notfall-Distanzunterricht: Analyse eines Policydiskurses und seiner Problemrepräsentationen. In A.M. Kamin, J. Holze, M. Wilde, K. Rummler, V. Dander, N. Grünberger & M. Schiefner-Rohs (Eds.), MedienPädagogik 20 (Jahrbuch Medienpädagogik) (pp. 347–374). Zürich: OAPublishing Collective Genossenschaft. https://doi.org/10.21240/mpaed/jb20/2023.09.14.X.

Büscher, B. (2022). The Nonhuman Turn: Critical Reflections on Alienation, Entanglement and Nature Under Capitalism. Dialogues in Human Geography, 12(1), 54–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/20438206211026200.

Callon, M. (1984). Some Elements of a Sociology of Translation: Domestication of the Scallops and the Fishermen of St Brieuc Bay. The Sociological Review, 32(1), 196–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.1984.tb00113.x.

Chan, A. S. (2014). Networking Peripheries: Technological Futures and the Myth of Digital Universalism. Cambridge: The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9360.001.0001.

DeSilvey, C. (2006). Observed Decay: Telling Stories with Mutable Things. Journal of Material Culture, 11(3), 318–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183506068808.

Domínguez Rubio, F. (2016). On the Discrepancy Between Objects and Things: An Ecological Approach. Journal of Material Culture, 21(1), 59–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183515624128.

Dussel, I. (2020). Educational Technology as School Reform: Using Actor-Network Theory to Understand Recent Latin American Educational Policies. In G. Fan & T. S. Popkewitz (Eds.), Handbook of Education Policy Studies: School/University, Curriculum, and Assessment, Volume 2 (pp. 35–53). Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-8343-4_2.

Dussel, I., & Trujillo Reyes, B. F. (2018). ¿Nuevas formas de enseñar y aprender?. Las posibilidades en conflicto de las tecnologías digitales en la escuela. Perfiles educativos, 40, 142–178. https://doi.org/10.22201/iisue.24486167e.2018.Especial.59182.

Feenberg, A. (1999). Questioning Technology. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203022313.

Ferrante, P., Williams, F., Büchner, F., Kiesewetter, S., Chitsauko Muyambi, G., Uleanya, C., & Utterberg Modén, M. (2023). In/Equalities in Digital Education Policy – Sociotechnical Imaginaries from Three World Regions. Learning, Media and Technology, 49(1), 122–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2023.2237870.

GEW - Gewerkschaft Erziehung und Wissenschaft, Hoffmann, I., & Klinger, A. (2019). Aktivitäten der Digitalindustrie im Bildungsbereich. https://www.gew.de/index.php?eID=dumpFile&t=f&f=91790&token=76e262551195777636f30dc9c5d78ceccf8db8bf&sdownload=&n=DigitalIndustrieBB-2019-A4-web.pdf. Accessed 24 June 2024.

Graham, S., & Thrift, N. (2007). Out of Order: Understanding Repair and Maintenance. Theory, Culture & Society, 24(3), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276407075954.

Hallam, E., & Ingold, T. (2014). Making and Growing: An Introduction. In E. Hallam, & T. Ingold (Eds.), Making and Growing: Anthropological Studies of Organisms and Artefacts (pp. 1–24). Farnham/Burlington: Ashgate.

Harper, D. (1987). Working Knowledge: Skill and Community in a Small Shop. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Heidegger, M. (1962). Being and Time. New York: Harper & Row.

Henke, C. R. (1999). The Mechanics of Workplace Order: Toward a Sociology of Repair. Berkeley Journal of Sociology, 44, 55–81.

Henke, C. R. (2019). Negotiating Repair: The Infrastructural Contexts of Practice and Power. In I. Strebel, A. Bovet, & P. Sormani (Eds.), Repair Work Ethnographies: Revisiting Breakdown, Relocating Materiality (pp. 255–282). Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-2110-8_9.

Jackson, S. J. (2014). Rethinking Repair. In T. Gillespie, P. J. Boczkowski, & K. A. Foot (Eds.), Media Technologies (pp. 221–240). Cambridge: The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9042.003.0015.

Jackson, S. J. (2019). Repair as Transition: Time, Materiality, and Hope. In I. Strebel, A. Bovet, & P. Sormani (Eds.), Repair Work Ethnographies: Revisiting Breakdown, Relocating Materiality (pp. 337–347). Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-2110-8_12.

Jandrić, P., Ryberg, T., Knox, J., Lacković, N., Hayes, S., Suoranta, J., Smith, M., Steketee, A., Peters, M., McLaren, P., Ford, D. R., Asher, G., McGregor, C., Stewart, G., Williamson, B., & Gibbons, A. (2019). Postdigital Dialogue. Postdigital Science and Education, 1(1), 163–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-018-0011-x .

Jasanoff, S., & Kim, S.-H. (2015). Dreamscapes of Modernity: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Fabrication of Power. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226276663.001.0001.

Julia, D. (1995). La culture scolaire comme objet historique. Paedagogica Historica, 31(1), 353–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/00309230.1995.11434853.