Abstract

Nineteen million people were diagnosed with cancer, and almost ten million cancer deaths were recorded worldwide in 2020. The extent of cancer stigmatisation can be as prevalent as 80%. 24% of advanced cancer patients have been diagnosed with an anxiety or depressive disorder. The aim is to provide valuable plans of how it may be conceptually possible to form an intervention from a public health perspective. Preliminary observations identified a gap in research of a novel framework for cancer stigma. It is hoped this knowledge will build the foundations to develop an explanatory evidence-based theoretical model for improving the understanding, evaluation and planning of cancer stigma. Less than 6% of current studies are aimed at actually implementing interventions into practise. Using the Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework as an example, whilst drawing upon the independently existing theoretical work on stigma mechanisms and mental health intervention strategies, widening the field of exploration, through mixed method analysis concerning cancer stigma to address the barriers at person, provider, and societal levels, will expand upon the initial application of theories and suggest ways of countering the broader attitudes and beliefs. Guiding future evidence-based initiatives, designed to target and address the many levels at which, cancer stigma can derive. It holds the potential to map out public health directives and strategies, targeting such a multidimensional facet, intricately interwoven across a myriad of levels, being able to support a rationale as to the origins of stigma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

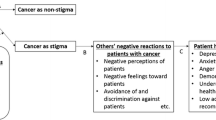

Nineteen million people were diagnosed with cancer, and almost ten million cancer deaths were recorded worldwide in 2020 [1]. Cancer stigma refers to the perception of the person affected by cancer as differing from the norm in a negative or undesirable way [2]. The extent of cancer stigmatisation can be as prevalent as 80% [3]. Cancer stigma can originate from preconceived opinions that are not based on reason or experience and can have potentially devastating consequences for those who have been given a cancer diagnosis, often leading to the depersonalisation of an individual, which, in turn, can present additional barriers, such as delays in seeking medical help and social isolation [4].

A variety of factors influence differences across types of cancer and associated features of perceived health-related stigma; for example, patients with lung cancer report feeling particularly stigmatised because of the association with behaviour, perceived to be personally controllable [5]. Surveys indicate people are hesitant to talk about colorectal cancer because of the stigma associated with the body parts involved and the aversion to the various screening options [6]. Skin cancer is often considered highly preventable in relation to risk factors [7]. Breast cancer can lead to feeling different or alienated from others due to perceptual changes. Cervical cancer is seen to be widely misunderstood, as a result of incautious behaviour [8].

Receiving a cancer diagnosis is likely to invoke a range of emotions, including worries, fears of uncertainties, and poor self-esteem [9]. 24% of advanced cancer patients have been diagnosed with an anxiety or depressive disorder, a higher value than that in healthy populations [10]. Diminished quality of life can also be experienced, particularly when individuals are avoided by family and friends, with a cancer patient’s emotional responses after a cancer diagnosis can influence both morbidity and mortality [11]. Although many cancer patients have expressed the opportunity to have open discussions about their diagnosis, many people assume talking about cancer with someone who has a diagnosis could arouse or exacerbate feelings of anxiety, depression, and hopelessness [12]. But communication is critical to increasing emotional support and decreasing cancer-related stigma. Combating the negative impacts of stigma holds the potential to play an important role in improving cancer patients’ quality of life.

Although previous studies considering cancer stigma have provided an invaluable appreciation, there has been a concentration on personal experiences and less than 6% of current studies are aimed at actually implementing interventions into practise [13]. Preliminary observations identified a gap in evidence-based research into the exploration of a combination of consistent contributors, disease and treatment characteristics, situational threats, and personal attributions, such as stress and coping, which could lead to an effective intervention. An intervention framework informed by insights from the tremendous variability across people, groups, and situations in response to cancer stigma needs to be addressed.

Devising such a multifaceted construct would offer a multi-level perspective. Moreover, the use of grounded theory studies needs to examine between differences in attitudes towards cancer types, using a multidimensional measure of cancer stigma, which could extend findings beyond personal responsibility attributions [5]. There is a comparison of how cancer stigma, death, and dying influence different cultural societies and how much impact this has on a suggested Cancer Stigma Framework [14], alongside rich data of experiences, including those of the patient, individuals connected to a person with cancer, and the general population. All necessary additions to the understanding, evaluation, and planning of a Cancer Stigma Framework are beneficial in the creation of an effective intervention and policy development.

Discussion

Standardised mental health interventions and group support are known to be used for patients with cancer. Trials have included evidence-based cognitive modalities, focusing on changing specific beliefs or thoughts by learning coping skills, such as cognitive behavioural therapy, dignity therapy, meaning-centred psychotherapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, and supportive expressive therapy [15]. Behaviour techniques, including relaxation and visualisation, have also proven useful, as many times, stress responses and subsequent psychological disorders can often depend on the reaction to everyday life events during illness [16].

Separately, frameworks to reduce cancer stigma have included a specific focus on education and intergroup contact, particularly concerning barriers towards end-of-life discussions. Projects have been funded to encourage engagement, such as The Conversation Project and last year; Marie Curie launched a county-specific initiative, The Somerset Talk About Project [17]. Advocacy organisations have intermittently released public awareness campaigns in attempts to lessen the stigma associated with dying within the community. Yet, it can be argued that blended elements of these standalone directives could further contribute towards societal changes.

In the context of mental health-related cancer stigma reduction, an intervention and an associated process and evaluation plan, aiming to focus on the cause and effects of mental health problems and stigma for those affected by cancer would be best informed by grounded theory studies, synonymous with grounded evidenced based practise more broadly. Avoidant attitudes can be more frequent amongst close social relationships, and due to the broad complexities of the stigma surrounding dying and death, a grounded intervention that can prove effective in increasing interpersonal empathy and understanding for both the individual and their support network could then impact behaviour change within wider intergroup social contexts.

The newly proposed Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework holds firm foundations to build upon, within the context of those affected by cancer. Such an intervention would not distinguish the stigmatised from the stigmatising, challenging hostility, and unreasonable opinions that differentiate individuals from the social norm, which is imperative to successful stigma-reducing interventions [18].

Sympathetically integrated after diagnosis, with an inclusion of a combination of cognitive and intergroup focus, this offering could better recognise implicit attitudes between affected individuals and their families and explore ways to change behaviours. Drawing upon cognitive techniques used within existing grounded mental health interventions, beneficial for interpersonal perception and attitudes of patients with cancer. Nuances connected to intergroup contact can be important to transcend stigma, highlighting common experiences of cancer and encouraging individuals to identify with others, whilst building strength within the community. These advances can enhance individual cognitive work, whilst at the same time, members can engage in community and public education, contributing to substantial strides towards the reduction of negative attitudes and cancer stigma, whilst promoting inclusivity within wider social group contexts.

Our findings highlight a lack of rigorous studies to adequately support efficacy research to overcome likely problems associated with cancer stigma. An increase in researching the intersection of novel integration models, alongside process evaluation plans, is needed, which include education and advocacy for public health policy changes, incorporating patients and their families. It will be imperative to consider implementation strategies from the point of development. Implementation science, such as the UK Medical Research Council’s complex intervention development guidance, offers supportive frameworks to ensure a dynamic iterative process [19]. During such phases, researchers, specialists, executives, and political leaders need to work closely together to ensure interventions can be successfully embedded.

The identification of social-psychological problems and the need to develop subsequent interventions hold the possibility to outpace capacity. Psychosocial oncology departments are reportedly understaffed and underfunded; therefore, such research identifications can be overlooked. The result of this is the proportion of cancer patients who receive optimal psychosocial support is far from uniform.

Conclusion

With no defined applied, theoretically grounded model to serve as a conceptual framework for cancer stigma, the authors are completing public health strategy and policy solutions mixed method research, concerning cancer stigma to address the barriers at person, provider, and societal levels.

To truly make a change, more theoretically grounded research and empirical evaluations are still required to further examine the cause of research inconsistencies and subconscious stigmatisation on a broader scale, within clinical practise and intervention development. Perhaps, implementing a reversed perspective, understanding the meanings attributed to the experience. Researchers within the domain are starting to ask questions, such as the fear of death a predictor for cancer stigma, to determine the origins of cancer stigma and its effects on mental health, and what is the impact of end-of-life discussions on delivery confidence, from a staff’s perspective. The results from such analysis could better guide suggestions for a successful grounded intervention, which will inform care plan directives and service changes, whilst improving compassion and honesty.

A multidimensional approach exploring the sources of stigma may support the understanding of strong predictors of avoidant behaviours and decrease the varying effects of structural stigma [20]. The offering is a single overarching grounded intervention principle to inform care plan directives and service changes, whilst enhancing quality of life, changing implicit attitudes and several advantages that could further explore how people talk, think, feel, and act. The economic value of such an intervention is unmeasurable, particularly when evidence strongly supports how any such an addition can have cascading benefits to the quality of care.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49.

Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Ann Rev Sociol. 2001;27(1):363–85.

Ernst J, Mehnert A, Dietz A, Hornemann B, Esser P. Perceived stigmatization and its impact on quality of life - results from a large register-based study including breast, colon, prostate and lung cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):741.

Wortman CB, Dunkel-Schetter C. Interpersonal relationships and cancer: a theoretical analysis. J Soc Issues. 1979;35(1):120–55.

Marlow LAV, Waller J, Wardle J. Does lung cancer attract greater stigma than other cancer types? Lung Cancer. 2015;88(1):104–7.

Jin Y, Zheng M-C, Yang X, Chen T-L, Zhang J-E. Patient delay to diagnosis and its predictors among colorectal cancer patients: a cross-sectional study based on the theory of planned behavior. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2022;60:102174.

Bowers JM, Nosek S, Moyer A. Young adults’ stigmatizing perceptions about individuals with skin cancer: the influence of potential cancer cause, cancer metaphors, and gender. Psychology & Health. 2021;1–18.

Peterson CE, Silva A, Goben AH, Ongtengco NP, Hu EZ, Khanna D, et al. Stigma and cervical cancer prevention: a scoping review of the US literature. Preventive Med. 2021;153:106849.

Else-Quest NM, Jackson TL. Cancer stigma. The stigma of disease and disability: Understanding causes and overcoming injustices. 2014;:165–81.

Kyota A, Kanda K. How to come to terms with facing death: a qualitative study examining the experiences of patients with terminal Cancer. BMC Palliat Care. 2019;18(1):33.

Holland JC. History of psycho-oncology: overcoming attitudinal and conceptual barriers. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(2):206–21.

Iverach L, Menzies RG, Menzies RE. Death anxiety and its role in psychopathology: reviewing the status of a transdiagnostic construct. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34(7):580–93.

Rankin NM, Butow PN, Hack TF, Shaw JM, Shepherd HL, Ugalde A, et al. An implementation science primer for psycho-oncology: translating robust evidence into practice. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology Research & Practice. 2019;1(3).

Baider L. Cultural diversity: family path through terminal illness. Annals of Oncology. 2012;23:iii62–iii65.

Kredentser MS, Chochinov HM. Psychotherapeutic considerations for patients with terminal illness. Am J Psychother. 2020;73(4):137–43.

Selene G-C, Omar C-IF, Silvia A-P. Palliative care, impact of cognitive behavioral therapy to cancer patients. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2016;217:1063–70.

Improving palliative care: the conversation project [Internet]. NHS choices. NHS; 2019 [cited 2022Dec12]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/atlas_case_study/improving-palliative-care-the-conversation-project/

Stangl AL, Earnshaw VA, Logie CH, van Brakel W, L CS, Barre I, et al. The health stigma and discrimination framework: a global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):31.

O’Cathain A, Croot L, Duncan E, Rousseau N, Sworn K, Turner KM, et al. Guidance on how to develop complex interventions to improve health and healthcare. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8):e029954.

Harper FWK, Schmidt JE, Beacham AO, Salsman JM, Averill AJ, Graves KD, et al. The role of social cognitive processing theory and optimism in positive psychosocial and physical behavior change after cancer diagnosis and treatment. Psychooncology. 2007;16(1):79–91.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of data were performed by Lucie-May Golbourn. Drafting of the article and critically revising for important intellectual content were completed by Rory Colman. Final approval of the version to be published was given by Yu Uneno and Yasuhiro Kotera.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Medicine

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Golbourn, LM., Colman, R., Uneno, Y. et al. A Need for Grounded Mental Health Interventions to Reduce Cancer Stigma. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 5, 114 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-023-01456-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-023-01456-6