Abstract

Stigma is a well-documented barrier to health seeking behavior, engagement in care and adherence to treatment across a range of health conditions globally. In order to halt the stigmatization process and mitigate the harmful consequences of health-related stigma (i.e. stigma associated with health conditions), it is critical to have an explicit theoretical framework to guide intervention development, measurement, research, and policy. Existing stigma frameworks typically focus on one health condition in isolation and often concentrate on the psychological pathways occurring among individuals. This tendency has encouraged a siloed approach to research on health-related stigmas, focusing on individuals, impeding both comparisons across stigmatized conditions and research on innovations to reduce health-related stigma and improve health outcomes. We propose the Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework, which is a global, crosscutting framework based on theory, research, and practice, and demonstrate its application to a range of health conditions, including leprosy, epilepsy, mental health, cancer, HIV, and obesity/overweight. We also discuss how stigma related to race, gender, sexual orientation, class, and occupation intersects with health-related stigmas, and examine how the framework can be used to enhance research, programming, and policy efforts. Research and interventions inspired by a common framework will enable the field to identify similarities and differences in stigma processes across diseases and will amplify our collective ability to respond effectively and at-scale to a major driver of poor health outcomes globally.

Background

Stigma is a well-documented global barrier to health-seeking behavior [1], engagement in care [2], and adherence to treatment [3] across a range of health conditions [4, 5]. As a distinguished and labelled difference [6], stigma, Goffman notes, enables varieties of discrimination that ultimately deny the individual/group full social acceptance, reduce the individuals’ opportunities [7], and fuel social inequalities [8]. Stigma influences population health outcomes by worsening, undermining, or impeding a number of processes, including social relationships, resource availability, stress, and psychological and behavioral responses, exacerbating poor health [9].

In order to intervene to halt the stigmatization process or mitigate the harmful consequences of health-related stigma, or stigma associated with health conditions, the existence of a clear, multi-level theoretical framework to guide intervention development, measurement, research, and policy is critical. Existing stigma frameworks typically focus on one health condition in isolation, for example, obesity/overweight [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17], HIV [8, 18,19,20,21,22,23], or mental health [24,25,26,27,28]. This tendency has encouraged a siloed approach to research on health-related stigmas, stifling innovative public health responses. Alderson argues that it is practical and scientific to examine theories, as they powerfully influence how evidence is collected, analysed, understood and used and notes that, when theories are implicit, their power to clarify or to confuse, and to reveal or obscure new insights, can work unnoticed [29]. As such, it is useful to have an explicit theoretical framework that can both guide research and intervention development on individual health conditions and allow for comparisons and responses across health conditions.

The majority of health-related stigma frameworks explore psychological pathways at the individual level, focusing either on the individuals experiencing stigma [10, 11, 14,15,16, 30, 31], those perpetuating stigma [21, 26], or both [20, 24, 32]. While critical to understanding the factors that facilitate and mediate the stigmatization process for individuals, these frameworks limit researchers’ ability to inform the multi-level interventions required to meaningfully influence the stigmatization process [33]. For some health conditions, including HIV [8, 18, 19, 23, 34, 35], mental health [27, 28], child health [35], and obesity/overweight [17], frameworks addressing the social (e.g. cultural and gender norms) and structural (e.g. legal environment and health policy) pathways leading to stigma, in addition to the individual pathways, have been proposed. A few general stigma frameworks have also highlighted the influence of social and structural forces on the stigmatization process across socio-ecological levels [6, 9, 36]. In the context of health-related stigma reduction, socio-ecological levels have been defined as public policy (national and local laws and policies), organizational (organizations, social institutions, workplaces), community (cultural values, norms, attitudes), interpersonal (family, friends, social networks), and individual (knowledge, attitudes, skills) [37].

Building from existing conceptualizations of health-related stigmas and practical experience in designing stigma-reduction interventions, we propose a new, crosscutting framework and demonstrate its application to a range of health conditions, including leprosy, epilepsy, mental health, cancer, HIV, and obesity/overweight. We discuss how stigma related to race, gender, sexual orientation, class, and occupation intersects with health-related stigmas, and examine how the framework can be used to enhance research, programming, and policy efforts. The framework is intended to amplify our collective ability to respond effectively and at-scale to a major driver of poor health outcomes globally.

The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework

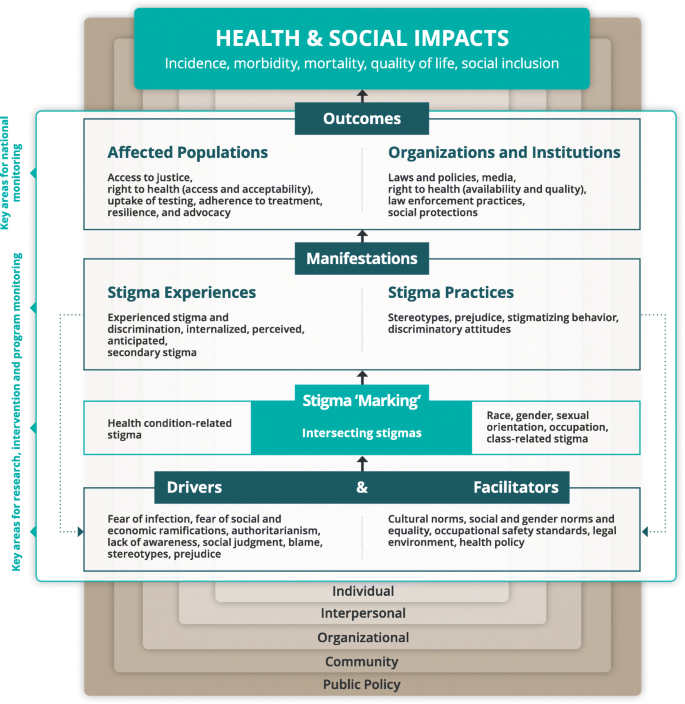

The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework (Fig. 1) articulates the stigmatization process as it unfolds across the socio-ecological spectrum in the context of health, which can vary across economic contexts in low-, middle-, and high-income countries. The process can be broken down into a series of constituent domains, including drivers and facilitators, stigma ‘marking’, and stigma manifestations, which influence a range of outcomes among affected populations, as well as organizations and institutions, that ultimately impact health and society.

The first domain refers to factors that drive or facilitate health-related stigma. Drivers vary by health condition, but are conceptualized as inherently negative [18]. They may range from fear of infection through casual contact for communicable diseases and concerns about productivity due to poor health for chronic conditions, to authoritarianism and social judgment and blame. Conversely, facilitators may be positive or negative influences [33], for example, the presence or absence of occupational safety standards and protective supplies in health facilities can minimize or exacerbate stigmatizing avoidance behaviors towards populations with infectious diseases by healthcare workers [38]. Drivers and facilitators determine whether stigma ‘marking’ occurs, through which a stigma is applied to people or groups according to a specific health condition or other perceived difference such as race, class, gender, sexual orientation, or occupation. Intersecting stigma occurs when people are ‘marked’ with multiple stigmas [39]. Once a stigma is applied, it manifests in a range of stigma experiences (i.e. lived realities) and practices (i.e. beliefs, attitudes, and actions). Stigma experiences can include experienced discrimination, which refers to stigmatizing behaviors that fall within the purview of the law in some places, such as refusal of housing [33], and experienced stigma, or stigmatizing behaviors that fall outside the purview of the law such as verbal abuse or gossip [33]. The legal distinction is included as responding to a stigma manifestation that is illegal may require a different response (e.g. litigation) compared with a manifestation that is not illegal. Another stigma experience is internalized or ‘self-stigma’, which is defined as a stigmatized group member’s own adoption of negative societal beliefs and feelings, as well as the social devaluation, associated with their stigmatized status [40]. Perceived stigma (i.e. perceptions about how stigmatized groups are treated in a given context) [41] and anticipated stigma (i.e. expectations of bias being perpetrated by others if their health condition becomes known) are also classified as stigma experiences [42]. Finally, secondary or ‘associative’ stigma, which refers to the experience of stigma by family or friends of members of stigmatized groups or among healthcare providers who provide care to members of stigmatized groups [43], is included under stigma experiences. Stigma practices can include stereotypes (i.e. beliefs about characteristics associated with the group and its members), prejudice (i.e. negative evaluation of the group and its members), stigmatizing behavior (i.e. exclusion from social events, avoidance behaviors, gossip), and discriminatory attitudes (i.e. belief that people with a specific health condition should not be allowed to participate fully in society). We included stereotypes and prejudice under ‘drivers’ and ‘manifestations’, as they both fuel and are reinforced by the stigmatization process.

We postulate that stigma manifestations subsequently influence a number of outcomes for affected populations, including access to justice, access to and acceptability of healthcare services, uptake of testing, adherence to treatment, resilience (i.e. the power to challenge stigma) [34, 44], and advocacy. They also influence outcomes for organizations and institutions, including laws and policies, the availability and quality of health services, law enforcement practices, and social protections.

While the framework is specific to health-related stigma, it recognizes that health-related stigma often co-occurs with other, intersecting stigmas, such as those related to sexual orientation, gender, race, occupation, and poverty. Therefore, incorporating intersecting stigmas into the framework is necessary, as stigma manifestations and health outcomes may be influenced by a range of stigmatizing circumstances that must be considered to understand the full impact of stigma [5, 36].

How is the framework different?

The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework differs from many other models in that it does not distinguish the ‘stigmatized’ from the ‘stigmatizer’ [21, 32]. The absence of this dichotomy is intentional, as we seek to challenge the ‘us’ versus ‘them’ distinction that enables people to set others apart as ‘different from the norm’, a key component of the stigmatization process described by Link and Phelan [6], which precedes stigma ‘marking’. As suggested by Parker and Aggleton [8], we seek to move away from psychological models that see stigma as a thing which individuals impose on others and instead emphasize, the broader social, cultural, political and economic forces that structure stigma.

According to Kippax et al. [45], the danger in separating ‘us’ from ‘them’, or ‘agency’ from ‘vulnerability’, is that it removes the power that vulnerable populations have to act upon the social contexts driving their experiences, behaviors, and actions. The dichotomy also leads to an oversimplified view of vulnerable populations as a group of individuals defined and connected only by the ‘attribute’ of vulnerability [45]. Our framework seeks to show the interconnections between power and vulnerability and how they are fluid and complex. We want to underscore that all individuals can anticipate, perceive, internalize, experience, or perpetuate health-related stigma, while acknowledging unique outcomes for affected populations. There are no clear-cut boundaries about who experiences and who perpetuates stigma, yet, as we highlight throughout each example, stigma intersects with other axes of disempowerment and marginalization (e.g. across race, class, gender) in ways that result in some persons being more disadvantaged by health-related stigma. Removing the ‘us’ versus ‘them’ dichotomy also makes the framework more palatable to change agents, such as community leaders, advocates, and policy-makers, as it highlights that all persons can act as change agents and underscores the need for self-reflection and awareness of biases.

Another difference from previous frameworks is the separation of manifestations into ‘experiences’ and ‘practices’. This distinction clarifies the pathways to various outcomes following the stigma-marking phase of the process. Those who experience, internalize, perceive, or anticipate health-related stigma face a range of possible outcomes, such as delayed treatment, poor adherence to treatment, or intensification of risk behavior, that may diminish their health and wellbeing. While outcomes are mostly negative, positive outcomes are possible; stigma has been known to foster resilience in marginalized populations [46] and fuel the formation of patient advocacy groups and advocacy efforts that have led to major policy changes to improve access to healthcare for some stigmatized conditions like HIV [36, 47]. Stigma practices, on the other hand, highlight how the stigmatization process can generate or reinforce stereotypes and prejudice towards people or groups living with or at risk of various health conditions and foster discriminatory attitudes that fuel social inequalities [8].

We also differentiated outcomes for affected populations (i.e. the stigmatized person or group, as well as their family, friends, or healthcare providers) from outcomes for organizations and institutions. Our framework seeks to demonstrate that stigma experiences and practices influence affected populations as well as organizations and institutions, which then together influence the health and social impacts of stigma. By articulating these outcomes, the framework highlights the need for multilevel interventions to respond to health-related stigma. It also focuses attention on the far-reaching influence of health-related stigma on societies as well as individuals.

Where to intervene?

Ideally, we want to interrupt the process prior to the application of stigma. Thus, interventions often target the removal of the drivers of stigma or the shifting of norms and policies that facilitate the stigmatization process [33]. However, once a stigma is applied to people with a specific disease or health condition and once it manifests in experiences or practices, interventions are needed to mitigate harm and shift harmful attitudes and behaviors that compromise the general health and wellbeing of affected communities. Stigma-reduction interventions are most effective when they include components directed at a range of actors and socio-ecological levels [37]. A multi-component intervention, for example, may seek to support individuals with leprosy to cope with experienced stigma and overcome internalized stigma, as well as reaching out to community members to shift harmful norms about leprosy through community dialogues or engaging local leaders to share anti-stigma messages [48]. Likewise, advocacy with policy-makers and community leaders about the benefits of syringe exchange programs to prevent transmission of HIV may be combined with training of law enforcement officers on harm reduction and proper implementation of laws that de-criminalize drug use [49].

What to monitor?

The availability of data on health-related stigma and discrimination is critical for improving interventions and programs to address them, yet such routine data are often lacking [33]. The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework indicates key areas of focus for program-, facility-, and national-level monitoring. At the program level, data on the drivers and facilitators of stigma are needed to inform appropriate interventions in a given context. Systematically collected information regarding the manifestations of stigma is required for researchers and program evaluators to assess the impact of interventions to reduce stigma or mitigate the related harmful consequences. Such information is also important for health facility administrators to identify when training or changes to institutional policies are required to ensure a stigma-free healthcare environment. Affected communities and advocates can use information on stigmatizing practices, as well as the experiences and realities of affected individuals, to raise awareness among the general population and policy-makers to facilitate change. At the national level, data on the outcomes of stigma for affected populations and for organizations and institutions is needed to inform funding for and the scale of programming to address health-related stigma. Such information will also help to identify gaps where new interventions or programs are required.

Why a new framework and how to use it?

Since sociologist Erving Goffman published his seminal work on stigma in 1963, research on stigma across the disciplines of sociology, psychology, social science, medicine, and public health have expanded, and much is now understood about how stigma operates and induces harm in the context of different diseases and identities. Yet, progress has stalled in our collective ability to tackle stigma and its harmful consequences. Therefore, cross-disciplinary and cross-disease research and collaboration are urgently required to move forward.

The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework is intended to be a broad, orienting framework, akin to Pearlin’s Stress Process Model, which was developed to give some conceptual organization to the diverse lines of research that were – and still are – underway [50]. It is our hope that the framework will enable stigma researchers across disciplines to standardize measures, compare outcomes and build more effective, cross-cutting interventions. In addition, researchers can use the framework to generate research foci, to explore multiple health issues, and consider the interaction between multiple identities, social inequalities and health issues. The framework can also point to areas where clinicians, program implementers, and policy-makers can focus greater attention to better meet the needs of and improve health outcomes among their clients, communities, and societies more broadly. Implementation science approaches can advance how we tailor and apply the framework to guide stigma and discrimination reduction interventions and policies, for example, in defining the target audience for change, what specific drivers and facilitators of stigma should be addressed, what intervention or policy components are appropriate to address them, and how to measure change in specific outcomes overtime.

Practical applications

To demonstrate the cross-cutting nature of the Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework, we examine how it applies to both communicable and non-communicable health conditions. We review health conditions in roughly chronological order to provide perspective on how health-related stigma has been applied to new and emerging conditions throughout the course of human history. While the different domains of stigma articulated in the framework may not apply in the exact same way across all health conditions, health-related stigmas share a number of commonalities that warrant underscoring.

Firstly, social exclusion rooted in stigma appears to be a response to threat, varying across health-related stigma to the degree to which the source of threat is physical (such as fear of biological contagion, fear of violence and harm) or symbolic (such as aversion based on perceptions that the person does not adhere to central cultural values). Across the various health-related stigmas, people negatively stereotype, display prejudice toward, and discriminate the group and its members, although the content of the stereotype (e.g. being promiscuous, unclean) and the rationalization for the bias differ across the groups. In addition, these conditions differ in the extent to which they are concealable and thus in the way people cope with and manage their stigmatized identity, but all involve anticipated, experienced, and internalized stigma. Finally, how people cope with and manage stigma often adversely affects their health, both in terms of the stress it causes and in the underutilization of services available to them. Table 1 highlights both the commonalties and differences in drivers, facilitators, intersecting stigmas, manifestations, outcomes, and impacts relevant to leprosy, epilepsy, mental health, cancer, HIV, and obesity/overweight, which are further explored below.

Leprosy

Leprosy is perhaps the oldest stigmatized health condition known to humankind [51]. Most major religious scriptures make mention of leprosy, often as a condition to be avoided and/or as a divine supernatural punishment for sin or breaking a taboo [52]. The notion that leprosy – or a group of skin diseases that included leprosy – was contagious was already present in the Old Testament of the Bible. Fear of contagion and social exclusion remains closely tied to the image of leprosy [53,54,55] and the belief that leprosy is hereditary is also widespread [54, 56]. Together, these factors drive the stigmatization process for people living with leprosy.

The fact that persons affected by leprosy often have a low socioeconomic status, a low level of education and little awareness of human rights increases people’s vulnerability to discrimination [57]. In South Asia, a low-caste background can add a further, intersecting layer of stigma, as is the case for women in many endemic countries [58]. The stigma attached to leprosy typically manifests as a ‘spoiled identity’ in the affected person, affecting status and reputation, including that of family members [54, 59]. Social participation may be severely restricted, including problems in finding or maintaining a job, reduced access to education, reduced opportunities in finding a marital partner or problems in ongoing marriages, and sexual health [52, 60,61,62].

Further, many persons affected seek to conceal their condition [63, 64]. Concealment causes stress and anxiety, but may also lead to a delay in presenting for diagnosis and treatment [65, 66]. When treatment is delayed, the severity of disability may increase [67, 68]. Others may opt to discontinue treatment rather than risk ‘being found out’ [64]. At the personal level, these outcomes of stigma lead to a number of negative impacts for people living with leprosy, such as reduced quality of life and mental wellbeing, including a much increased risk of anxiety and depression [69, 70]. At the organizational level, leprosy-related stigma outcomes may include poor quality of health services and increased staff turnover. At the societal level, the combined impact of these outcomes may be prolonged transmission of bacilli in the community.

Epilepsy

Epilepsy is a neurological condition characterized by chronic or recurrent seizures. Seizures can lead to individuals crying out, collapsing, bleeding or foaming from the mouth, and losing control of urine and/or stools, and can therefore be frightening to those experiencing or witnessing them. Epilepsy is both concealable and unpredictable – it may be impossible to know that someone has epilepsy until they experience a seizure and it may be impossible to predict the onset of a seizure. Epilepsy-related stigma is largely driven by concerns about productivity and longevity, and fear of infection. Members of the general public endorse beliefs that people with epilepsy cannot contribute meaningfully to society and are poor prospects for marriage and employment [71,72,73]. Moreover, despite epilepsy not being contagious, some believe that epilepsy is contagious through saliva [74]. Such fears of contagion may be particularly problematic when they are endorsed by first responders, including police officers [75].

Religious and supernatural beliefs act as facilitators of epilepsy-related stigma in some contexts, with some believing that epilepsy is a curse or caused by witchcraft [76]. Risk factors for epilepsy include other health issues (e.g. cerebral palsy, birth asphyxia, stroke) and injuries (e.g. traumatic brain injury), and therefore epilepsy-related stigma may intersect with these other health-related stigmas. People with epilepsy experience a number of manifestations, such as social rejection and exclusion in a range of contexts, including familial and romantic [77]. Children with epilepsy have lower educational achievement and adults with epilepsy experience discrimination within the workplace [76]. Adults with uncontrolled seizures are less likely to be employed and more likely to report job problems when employed [77]. Outcomes of epilepsy-related stigma include lower self-efficacy surrounding treatment engagement and lower medication adherence [4]. Institutional outcomes include stigmatizing policies such as driving and/or employment restrictions that may be disproportionate to illness severity [78]. Epilepsy-related stigma ultimately undermines the quality of life of people living with epilepsy [72].

Mental health

Mental health-related stigma is often grounded in stereotypes that persons with mental health issues are dangerous (unpredictable, violent), responsible for their mental health issue, cannot be controlled nor recover, and should be ashamed [79]. Persons with mental health issues are often viewed as incompetent and unable to work or live independently [79]. Negative public attitudes, opinions, and intentions persist and are reported across diverse global contexts [80,81,82,83]. For instance, findings from the Stigma in Global Context – Mental Health Study, examining responses to scenarios of depression and schizophrenia in 16 countries [84], indicated that core ‘backbone’ stigmatizing beliefs remain across settings with regards to having a person with mental health issues provide childcare, teach children, marry into the family, attempt self-harm, or hold authority positions.

Race and gender appear to intersect with mental health-related stigma, influencing its severity. For example, a higher risk for psychiatric disorders among Caribbean-born versus US-born black men has been reported [85] and greater embarrassment in seeking mental health care has been reported among Somalian-born participants compared to US-born black participants [86]. Certain mental health concerns are perceived as masculine (e.g. addiction, antisocial personality disorder) and others as feminine (e.g. eating disorder), and public stigma towards issues perceived as masculine appears to be higher than towards those perceived as feminine [87, 88]. There are also gender differences in perceived stigma, where men may experience elevated stress regarding disclosing mental health issues in comparison to women [89]. Anticipated and perceived stigma are common manifestations of mental health-related stigma, contributing to fear of acknowledging one’s mental health issue and possibly leading to shame and avoidance regarding seeking mental health care [90, 91]. Mental health-related stigma also has a profound influence on life opportunities and persons realizing their goals and potential; it is associated with lower self-efficacy and self-esteem and compromised engagement in employment and independent living [92].

Public policy responses in some countries have gone a long way towards reducing or ameliorating the harmful effects of mental health-related stigma at the organizational and institutional levels. For example, in the US, the Americans with Disabilities Act [93] enacted in 1990 called for preventing discrimination on the basis of mental health and for the social inclusion and participation of persons with mental health issues in society. In 1999, this was followed by Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General [94] to inform the public of mental health issues and raise awareness of stigma and discrimination. Additionally, California’s Mental Health Services Act in 2004 [95] addressed stigma at institutional, societal and individual levels, including social marketing, training, and a focus on cultural competence.

Cancer

Cancer encompasses a large group of diseases characterized by the uncontrolled growth and spread of abnormal cells. Despite the fact that many cancers can be cured or at least effectively controlled, it remains a highly stigmatized condition, with some types of cancer more stigmatized than others [96]. One key factor in the stigmatization of different types of cancer involves perceptions of the individual’s responsibility for having the disease. For example, cancers of the lung are highly stigmatized [1] due to the belief that smoking is their primary cause, which is believed to be under the person’s control [97]. Most people have negative explicit and implicit attitudes toward smoking and those who smoke [98], which may further strengthen the stigmatization of people with lung cancer. A second factor underlying cancer-related stigma is the degree to which the disease causes apparent disfigurement such as cancers of the throat or mouth. As with other physical conditions, such as weight loss/gain or leprosy, the physical abnormalities associated with some forms of cancer activate the behavioral immune system, eliciting negative emotions such as disgust or aversion, distancing, and avoidance [99].

The experience of cancer-related stigma has important psychological, physical, and social consequences. Psychologically, it is associated with depression, anxiety, and demoralization among patients with cancer [100]. Individuals who experience greater cancer-related stigma tend to delay more in seeking medical care [101] and often attempt to conceal their disease from others [102]. To the extent to which people experience stigma and shame associated with their disease, such as is common with people with lung cancer, they often experience disruption in their personal relationships and decreased marital satisfaction, as well as increased depression, particularly when they blame themselves for their illness [103]. Greater internalization of cancer-related stigma leads to lower self-esteem and poorer mental health, smaller social networks and less opportunity to receive social support, and greater anticipated social rejection, all of which compromise the quality of life [104].

The stigma associated with cancer varies across religions and related cultures. Although women who are members of ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities are at heightened risk for both breast and ovarian cancer due to an increased probability of being carriers of certain genes associated with these cancers given their Eastern and Central European ancestry, they tend to have low screening rates, low health literacy, and poor health practices because of the stigmatization of cancer in these communities [105]. Fears that a diagnosis of breast cancer will dim prospects for arranged marriages have been shown to discourage single Muslim women from accessing treatment for breast cancer in Pakistan [106]. Similarly, South Asian immigrant women of many different faiths in Canada share the belief that having a breast cancer diagnosis would threaten a family’s social status and lead to spousal rejection [106].

HIV

HIV is a potentially life-threatening disease caused by a virus that weakens the immune system and spreads through blood and sexual contact. HIV-related stigma is driven by several factors, including (1) fear of infection, where people living with HIV (PLHIV) may be perceived as threatening due to the infectious nature of HIV; (2) concerns about productivity and longevity, where PLHIV may be perceived as poor prospects for employment, friendships, and romantic relationships; and (3) social norm enforcement, since HIV risk is related to a range of socially stigmatized behaviors (e.g. same-sex sexual relations, injection drug use, sex work) and therefore PLHIV are devalued due to their perceived associations with these behaviors [107, 108]. Factors that facilitate HIV stigma range from laws that criminalize HIV transmission or specific professions (e.g. sex work) or behaviors (e.g. same-sex sexual relations, injection drug use) to the lack of universal protection supplies in health facilities. Key populations for HIV include men who have sex with men, people with histories of injection drug use, racial and ethnic minorities, and sex workers, and therefore stigmas that intersect with HIV include those associated with sexual orientation, substance use, race, and occupation [36, 109].

PLHIV, including adolescents and young people, report a range of stigmatizing experiences from others, including social rejection, exclusion, gossip, and poor healthcare, and are at risk of internalizing stigma [110]. The level of HIV stigma in communities and societies influences a number of stigma practices, such as discriminatory attitudes among the general public and healthcare workers, and harmful stereotypes and prejudices that can lead to stigmatizing behavior towards PLHIV (exclusion, verbal abuse, etc.). Outcomes of HIV stigma for people at risk of or living with HIV include engagement in greater HIV risk behaviors, lower rates of HIV testing, worse engagement and retention in HIV care, and worse initiation and adherence to medication [3, 44, 111]. Institutional outcomes include stigmatizing policies such as those that criminalize PLHIV who do not disclose their HIV status to their partners or prohibit PLHIV from traveling. Finally, HIV-related stigma has downstream effects on HIV incidence as well as morbidity, mortality, and quality of life for PLHIV [3, 109].

Overweight and obesity

The stigma associated with weight is particularly strong, pervasive, and openly expressed. There seem to be minimal social norms prohibiting weight shaming, making it particularly problematic. It develops relatively early in socialization, emerging as early as 31 months [112]. Obesity and overweight are often perceived as culturally non-normative, and therefore people with obesity or overweight are often perceived unfavorably, negatively stereotyped, and discriminated against. Additionally, since weight is generally perceived as personally controllable, overweight implies negative personal qualities. Individuals with obesity are often blamed for their weight status and stereotyped as lazy, lacking willpower, incompetent, and unattractive, particularly in cultures that hold core values, such as the Protestant Work Ethic, that emphasize self-control and hard work [113]. In addition to concerns about character, because obesity and overweight are perceived as abnormal physical features, they may activate the behavioral immune system [99] and elicit disgust and related concerns about disease avoidance [114], which leads to distancing and other direct forms of social rejection. Weight-based disparities are well documented in employment, healthcare, education, and interpersonal outcomes [115, 116].

Experiencing and anticipating weight-based stigma (including discrimination, teasing and bullying, social rejection, and other forms of unfair treatment) adversely affects the mental and physical health of people with overweight or obesity [117]. Psychologically, experiencing greater weight-based discrimination is associated with heightened distress (including depression and anxiety) and low self-esteem generally, as well as demoralization and diminished confidence in being able to pursue health-promoting behaviors. Physically, people who experience greater weight-based stigma display less cardiovascular fitness, muscular strength, and endurance [118]. Further, since exposure to weight-based stigma generally reduces motivation, intentions, and feelings of efficacy related to engaging in health-promoting behaviors, weight-based stigma has adverse effects on weight management. Consequently, experiencing more weight-based stigmatization predicts greater caloric consumption and reduced energy expenditure during weight-loss treatment [119]. Thus, weight stigma may contribute to obesity-related health problems due to added stress and reduced engagement in health-promoting behaviors, which jointly operate to increase or maintain excess weight.

In healthcare settings, women who perceive stigmatization from their providers report delaying use of preventive health services for fear of being judged or embarrassed [120]. This avoidance of care allows for untreated problems to progress to a more advanced stage that may be more difficult to treat, thus exacerbating health problems. Moreover, these psychological, physical, motivational, and behavioral effects of weight-based stigma are particularly strong among individuals who internalize this stigma to a greater degree. In terms of responses at the public policy level, there are currently no federal laws against weight-based discrimination; however, one state (Michigan), and a limited number of cities in the US, legally prohibit weight-based discrimination.

Discussion

The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework provides an innovative and alternative method to conceptualize and respond to health-related stigmas. Applicable across a range of health conditions and diseases, the framework highlights the domains and pathways common across health-related stigmas and suggests key areas for research, intervention, monitoring, and policy. This crosscutting approach will support a more efficient and effective response to addressing a significant source of poor health outcomes globally.

The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework has practical applications for program implementers, policy-makers, and researchers alike, providing a ‘common ground’ to inform discourse around research priorities, developing innovative responses and implementing them at scale. For program implementers, the framework can inform the combination and level of interventions most appropriate for responding to a specific type of health-related stigma. For policy-makers, the framework has the potential to lead to efficiencies in funding for and implementation of efforts to reduce health-related stigmas. Lastly, for researchers, the framework should enable more concise and comparable measures of stigma that can be compared across health conditions and diseases by removing the disease siloes of the past and replacing them with common domains and terminology that is more accessible. The framework should also enable crosscutting research endeavors to develop and test interventions that more appropriately address the lived realities of vulnerable populations accessing healthcare systems.

People are not defined by just one disease or one perceived difference, they have complex realities in which to maneuver in order to protect their health and wellbeing, and public health interventions must be responsive to these realities.

References

Scott N, Crane M, Lafontaine M, Seale H, Currow D. Stigma as a barrier to diagnosis of lung cancer: patient and general practitioner perspectives. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2015;16(06):618–22.

Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am Psychol. 2004;59(7):614–25.

Mahajan AP, et al. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS. 2008;22(Suppl 2):S67–79.

DiIorio C, et al. The association of stigma with self-management and perceptions of health care among adults with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2003;4(3):259–67.

Link B, Hatzenbuehler ML. Stigma as an Unrecognized Determinant of Population Health: Research and Policy Implications. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2016;41(4):653–73.

Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing Stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27(1):363–85.

Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc.; 1963.

Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(1):13–24.

Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a Fundamental Cause of Population Health Inequalities. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):813–21.

Barlösius E, Philipps A. Felt stigma and obesity: Introducing the generalized other. Soc Sci Med. 2015;130:9–15.

Tomiyama AJ. Weight stigma is stressful. A review of evidence for the Cyclic Obesity/Weight-Based Stigma model. Appetite. 2014;82:8–15.

Abu-Odeh D. Fat stigma and public health: a theoretical framework and ethical analysis. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 2014;24(3):247–65.

DeJoy SB, Bittner K. Obesity Stigma as a Determinant of Poor Birth Outcomes in Women with High BMI: A Conceptual Framework. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(4):693–9.

Sikorski C, Luppa M, Luck T, Riedel-Heller SG. Weight stigma ‘gets under the skin’-evidence for an adapted psychological mediation framework-a systematic review. Obesity. 2015;23(2):266–76.

Ratcliffe D, Ellison N. Obesity and Internalized Weight Stigma: A Formulation Model for an Emerging Psychological Problem. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2015;43(02):239–52.

Himmelstein MS, Puhl RM, Quinn DM. Intersectionality: An Understudied Framework for Addressing Weight Stigma. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(4):421–31.

Puhl RM, Heuer CA. Obesity stigma: important considerations for public health. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(6):1019–28.

Stangl AL, Brady L, Fritz K. Measuring HIV stigma and discrimination. Washington, D.C.: International Center for Research on Women; 2012.

Stangl A, Sievwright K. HIV-Related Stigma and Children. In: A Clinical Guide to Pediatric HIV. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 297–315.

Earnshaw VA, Chaudoir SR. From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: a review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(6):1160–77.

Misir P. Structuration Theory. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2015;14(4):328–34.

Steward WT, et al. HIV-related stigma: Adapting a theoretical framework for use in India. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(8):1225–35.

Holzemer WL, et al. A conceptual model of HIV/AIDS stigma from five African countries. J Adv Nurs. 2007;58(6):541–51.

Fox AB, Earnshaw VA, Taverna EC, Vogt D. Conceptualizing and measuring mental illness stigma: The mental illness stigma framework and critical review of measures. Stigma Heal. 2018;3(4):348–76.

Yang LH, et al. A theoretical and empirical framework for constructing culture-specific stigma instruments for Chile. Cad saude coletiva. 2013;21(1):71–9.

Longdon E, Read J. ‘People with Problems, Not Patients with Illnesses’: Using Psychosocial Frameworks to Reduce the Stigma of Psychosis. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2017;54(1):24–8.

Pescosolido BA, Martin JK, Lang A, Olafsdottir S. Rethinking theoretical approaches to stigma: A Framework Integrating Normative Influences on Stigma (FINIS). Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(3):431–40.

Mukolo A, Heflinger CA, Wallston KA. The Stigma of Childhood Mental Disorders: A Conceptual Framework. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(2):92–103.

Alderson P. The importance of theories in health care. BMJ. 1998;317(7164):1007–10.

Schabert J, Browne JL, Mosely K, Speight J. Social Stigma in Diabetes. Patient - Patient-Centered Outcomes Res. 2013;6(1):1–10.

Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma ‘get under the skin’? A psychological mediation framework. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(5):707–30.

Weiss MG. Stigma and the Social Burden of Neglected Tropical Diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2(5):e237.

Stangl AL, Lloyd JK, Brady LM, Holland CE, Baral S. A systematic review of interventions to reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination from 2002 to 2013: how far have we come? J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(Suppl 2):3.

Earnshaw VA, Bogart LM, Dovidio JF, Williams DR. Stigma and racial/ethnic HIV disparities: moving toward resilience. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4):225–36.

Nayar US, Stangl AL, De Zalduondo B, Brady LM. Reducing stigma and discrimination to improve child health and survival in low-and middle-income countries: Promising approaches and implications for future research. J Health Commun. 2014;19 Suppl 1(sup1):142–63.

Logie CH, James L, Tharao W, Loutfy MR. HIV, Gender, Race, Sexual Orientation, and Sex Work: A Qualitative Study of Intersectional Stigma Experienced by HIV-Positive Women in Ontario, Canada. PLoS Med. 2011;8(11):e1001124.

Heijnders M, Van Der Meij S. The fight against stigma: An overview of stigma-reduction strategies and interventions. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11(3):353–63.

Pulerwitz J, Oanh KTH, Akinwolemiwa D, Ashburn K, Nyblade L. Improving hospital-based quality of care by reducing HIV-related stigma: evaluation results from Vietnam. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(2):246–56.

Hargreaves J, et al. P14.14 Intersecting stigmas: a framework for data collection and analysis of stigmas faced by people living with hiv and key populations. Sex Transm Infect. 2015;91(Suppl 2):A203.1–A203.

Rao D, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of the unity workshop: an internalized stigma reduction intervention for African American women living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(10):614–20.

Zelaya CE, Sivaram S, Johnson SC, Srikrishnan AK, Suniti S, Celentano DD. Measurement of self, experienced, and perceived HIV/AIDS stigma using parallel scales in Chennai, India. AIDS Care. 2012;24(7):846–55.

Quinn DM, Chaudoir SR. Living with a concealable stigmatized identity: The impact of anticipated stigma, centrality, salience, and cultural stigma on psychological distress and health. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;97(4):634–51.

Holzemer WL, et al. Measuring HIV stigma for PLHAs and nurses over time in five African countries. SAHARA J J Soc Asp HIV/AIDS Res Alliance. 2009;6(2):76–82.

Logie CH, et al. Pathways From HIV-Related Stigma to Antiretroviral Therapy Measures in the HIV Care Cascade for Women Living With HIV in Canada. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77(2):144–53.

Kippax S, Stephenson N, Parker RG, Aggleton P. Between individual agency and structure in HIV prevention: understanding the middle ground of social practice. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(8):1367–75.

Trapence G, et al. From personal survival to public health: community leadership by men who have sex with men in the response to HIV. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):400–10.

Kerrigan D, et al. A community empowerment approach to the HIV response among sex workers: effectiveness, challenges, and considerations for implementation and scale-up. Lancet. 2015;385(9963):172–85.

Peters RM, Dadun, Zweekhorst MB, Bunders JF, Irwanto, van Brakel WH. A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Intervention Study to Assess the Effect of a Contact Intervention in Reducing Leprosy-Related Stigma in Indonesia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(10):e0004003.

Martinez AN, Bluthenthal RN, Lorvick J, Anderson R, Flynn N, Kral AH. The impact of legalizing syringe exchange programs on arrests among injection drug users in California. J Urban Health. 2007;84(3):423–35.

Pearlin L. The Stress Process Revisited: Reflections on Concepts and Their Interrelationships. In: Aneshensel C, Phelan J, editors. Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health. New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers-Plenum Publishers; 1999. p. 395–415.

Jopling WH. Leprosy Stigma. Lepr Rev. 1991;62:0305–7518, 1–12.

Try L. Gendered experiences: marriage and the stigma of leprosy. Asia Pacific Disabil Rehabil J. 2006;17(2):55–72.

de Stigter DH, de Geus L, Heynders ML. Leprosy: between acceptance and segregation. Community behaviour towards persons affected by leprosy in eastern Nepal. Lepr Rev. 2000;71(4):492–8.

Engelbrektsson U. Challenged Lives: A Medical Anthropological Study of Leprosy in Nepal. Göteborg: University of Gothenburg; 2012.

Peters RMH, Dadun, Mimi Lusli, et al. The meaning of leprosy and everyday experiences: An exploration in Cirebon, Indonesia. J Trop Med. 2013;2013(Article ID 507034):10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/507034.

Schuller I, et al. The way women experience disabilities and especially disabilities related to leprosy in rural areas in South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Asia Pacific Disabil Rehabil J. 2010;21(1):60–70.

Sermrittirong S, van Brakel WH. Stigma in leprosy: concepts, causes and determinants. Lepr Rev. 2014;85(1):36–47.

Dijkstra JIR, van Brakel WH, van Elteren M. Gender and leprosy-related stigma in endemic areas: A systematic review. Lepr Rev. 2017;88:3.

Dako-Gyeke M. Courtesy stigma: A concealed consternation among caregivers of people affected by leprosy. Soc Sci Med. 2018;196:190–6.

van Brakel WH, et al. Disability in people affected by leprosy: the role of impairment, activity, social participation, stigma and discrimination. Glob Health Action. 2012;5:1–11.

van’t Noordende AT, van Brakel WH, Banstola N, Dhakal KP. The impact of leprosy on marital relationships and sexual health among married women in eastern Nepal. J Trop Med. 2016;2016:4230235.

Raju MS, Reddy JVS. Community attitude to divorce in leprosy. Indian J Lepr. 1995;67(4):389–403.

Peters RMH, et al. Narratives around concealment and agency for stigmareduction: A study of women affected by leprosy in Cirebon District, Indonesia. Disabil CBR Incl Dev. 2014;25(4):5–21.

Heijnders ML. The Dynamics of Stigma in Leprosy. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 2004;72(4):437.

Barrett R. Self-mortification and the stigma of leprosy in northern India. Med Anthr. 2005;19:0745–5194 LA–eng PT–Journal Article SB–IM, pp. 216–230.

Nicholls PG, Wiens C, Smith WCS. Delay in Presentation in the Context of Local Knowledge and Attitude Towards Leprosy—The Results of Qualitative Fieldwork in Paraguay. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 2003;71(3):198.

Van Veen NHJ, Meima A, Richardus JH. The relationship between detection delay and impairment in leprosy control: a comparison of patient cohorts from Bangladesh and Ethiopia. Lepr Rev. 2006;77(4):356–65.

Meima A, Saunderson PR, Gebre S, Desta K, van Oortmarssen GJ, Habbema JD. Factors associated with impairments in new leprosy patients: the AMFES cohort. Lepr Rev. 1999;70(2):189–203.

Tsutsumi A, Izutsu T, Md Islam A, Maksuda AN, Kato H, Wakai S. The quality of life, mental health, and perceived stigma of leprosy patients in Bangladesh. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(12):2443–53.

Yamaguchi N, Poudel KC, Jimba M. Health-related quality of life, depression, and self-esteem in adolescents with leprosy-affected parents: Results of a cross-sectional study in Nepal. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):22.

Demirci S, Dönmez CM, Gündoǧar D, Baydar ÇL. Public awareness of, attitudes toward, and understanding of epilepsy in Isparta, Turkey. Epilepsy Behav. 2007;11(3):427–33.

Fiest KM, Birbeck GL, Jacoby A, Jette N. Stigma in Epilepsy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2014;14(5):444.

Senanayake N, Román GC. Epidemiology of epilepsy in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 1993;71(2):247–58.

Tran D-S, et al. Epilepsy in Laos: knowledge, attitudes, and practices in the community. Epilepsy Behav. 2007;10(4):565–70.

Mbewe E, Haworth A, Atadzhanov M, Chomba E, Birbeck GL. Epilepsy-related knowledge, attitudes, and practices among Zambian police officers. Epilepsy Behav. 2007;10(3):456–62.

Baskind R, Birbeck G. Epilepsy Care in Zambia: A Study of Traditional Healers. Epilepsia. 2005;46(7):1121–6.

Morrell MJ. Stigma and epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2002;3(6S2):21–5.

Jacoby A, Austin JK. Social stigma for adults and children with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2007;48(Suppl 9):6–9.

Angermeyer MC, Dietrich S. Public beliefs about and attitudes towards people with mental illness: a review of population studies. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2006;113(3):163–79.

Pescosolido BA, Martin JK, Long JS, Medina TR, Phelan JC, Link BG. "A disease like any other"? A decade of change in public reactions to schizophrenia, depression, and alcohol dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(11):1321–30.

Phelan JC, Link BG, Stueve A, Pescosolido BA. Public Conceptions of Mental Illness in 1950 and 1996: What Is Mental Illness and Is It to be Feared? J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41(2):188–207.

Weiss SM, Zulu R, Jones DL, Redding CA, Cook R, Chitalu N. The Spear and Shield intervention to increase the availability and acceptability of voluntary medical male circumcision in Zambia: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet HIV. 2015;2(5):e181–9.

Schomerus G, et al. Evolution of public attitudes about mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125(6):440–52.

Pescosolido BA, Medina TR, Martin JK, Long JS. The ‘backbone’ of stigma: Identifying the Global core of public prejudice associated with mental illness. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):853–60.

Williams DR, Haile R, González HM, Neighbors H, Baser R, Jackson JS. The mental health of Black Caribbean immigrants: results from the National Survey of American Life. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):52–9.

Henning-Smith C, Shippee TP, McAlpine D, Hardeman R, Farah F. Stigma, discrimination, or symptomatology differences in self-reported mental health between US-born and Somalia-born Black Americans. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):861–7.

Boysen G, Ebersole A, Casner R, Coston N. Gendered mental disorders: masculine and feminine stereotypes about mental disorders and their relation to stigma. J Soc Psychol. 2014;154(6):546–65.

Wirth JH, Bodenhausen GV. The role of gender in mental-illness stigma: a national experiment. Psychol Sci. 2009;20(2):169–73.

Brown RL, Moloney ME, Brown J. Gender differences in the processes linking public stigma and self-disclosure among college students with mental illness. J Community Psychol. 2018;46(2):202–12.

Link BG, Yang LH, Phelan JC, Collins PY. Measuring mental illness stigma. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(3):511–41.

Pattyn E, Verhaeghe M, Sercu C, Bracke P. Public Stigma and Self-Stigma: Differential Association With Attitudes Toward Formal and Informal Help Seeking. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(2):232–8.

Corrigan PW, Rafacz J, Rüsch N. Examining a progressive model of self-stigma and its impact on people with serious mental illness. Psychiatry Res. 2011;189(3):339–43.

Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990, Pub. L. No. 101-336, 104 Stat. 328 (1990).

Carter R, Satcher D, Coelho T. Addressing Stigma Through Social Inclusion. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):773.

Clark W, et al. California’s historic effort to reduce the stigma of mental illness: the Mental Health Services Act. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):786–94.

J. Penner, L, Phelan, S, Earnshaw, V, Albrecht, T, Dovidio, “Patient stigma, medical interactions, and healthcare disparities: A selective review.,” in The Oxford Handbook of Stigma, Discrimination, and Health, B Dovidio, J Link, Ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018, 183–201.

Marlow LA, Waller J, Wardle J. Does lung cancer attract greater stigma than other cancer types? Lung Cancer. 2015;88(1):104–7.

Robinson MD, Meier BP, Zetocha KJ, McCaul KD. Smoking and the Implicit Association Test: When the Contrast Category Determines the Theoretical Conclusions. Basic Appl Soc Psych. 2005;27(3):201–12.

Park JH, Schaller M, Crandall CS. Pathogen-avoidance mechanisms and the stigmatization of obese people. Evol Hum Behav. 2007;28(6):410–4.

Fujisawa D, Hagiwara N. Cancer Stigma and its Health Consequences. Curr Breast Cancer Rep. 2015;7(3):143–50.

Carter-Harris L, Hermann CP, Schreiber J, Weaver MT, Rawl SM. Lung cancer stigma predicts timing of medical help-seeking behavior. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(3):E203–10.

Gonzalez BD, Jim HSL, Cessna JM, Small BJ, Sutton SK, Jacobsen PB. Concealment of lung cancer diagnosis: prevalence and correlates. Psychooncology. 2015;24(12):1774–83.

Dirkse D, Lamont L, Li Y, Simonič A, Bebb G, Giese-Davis J. Shame, guilt, and communication in lung cancer patients and their partners. Curr Oncol. 2014;21(5):e718–22.

Chambers SK, et al. Psychological distress and quality of life in lung cancer: the role of health-related stigma, illness appraisals and social constraints. Psychooncology. 2015;24(11):1569–77.

Tkatch R, et al. Barriers to Cancer Screening Among Orthodox Jewish Women. J Community Health. 2014;39(6):1200–8.

Bedi M, Devins GM. Cultural considerations for South Asian women with breast cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(1):31–50.

Phelan JC, Link BG, Dovidio JF. Stigma and prejudice: One animal or two? Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(3):358–67.

Herek GM. AIDS and Stigma. Am Behav Sci. 1999;42(7):1106–16.

Logie CH, et al. HIV-related stigma, racial discrimination, and gender discrimination: Pathways to physical and mental health-related quality of life among a national cohort of women living with HIV. Prev Med (Baltim). 2018;107:36–44.

Earnshaw VA, et al. Exploring Treatment Needs and Expectations for People Living with HIV in South Africa: A Qualitative Study. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:2543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2101-x1-10.

Katz IT, et al. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16((Suppl 2):3.

Ruffman T, O’Brien KS, Taumoepeau M, Latner JD, Hunter JA. Toddlers’ bias to look at average versus obese figures relates to maternal anti-fat prejudice. J Exp Child Psychol. 2016;142:195–202.

Crandall CS. Prejudice against fat people: ideology and self-interest. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;66(5):882–94.

van Leeuwen F, Hunt DF, Park JH. Is Obesity Stigma Based on Perceptions of Appearance or Character? Theory, Evidence, and Directions for Further Study. Evol Psychol. 2015;13(3):147470491560056.

Puhl RM, Heuer CA. The Stigma of Obesity: A Review and Update. Obesity. 2009;17(5):941–64.

Spahlholz J, Baer N, König H-H, Riedel-Heller SG, Luck-Sikorski C. Obesity and discrimination - a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Obes Rev. 2016;17(1):43–55.

J. Dovidio, L. Penner, S. Calabrese, and R. Pearl, “Physical Health Disparities and Stigma Race Sexual Orientation and Body Weight,” in The Oxford Handbook of Stigma, Discrimination, and Health, B. Major, J. Dovidio, and B. Link New York: Oxford University Press. 2018. p. 576.

Greenleaf C, Petrie TA, Martin SB. Relationship of weight-based teasing and adolescents’ psychological well-being and physical health. J Sch Health. 2014;84(1):49–55.

Wott CB, Carels RA. Overt Weight Stigma, Psychological Distress and Weight Loss Treatment Outcomes. J Health Psychol. 2010;15(4):608–14.

Phelan SM, Burgess DJ, Yeazel MW, Hellerstedt WL, Griffin JM, van Ryn M. Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obes Rev. 2015;16(4):319–26.

Acknowledgements

This article is part of a collection that draws upon a 2017 workshop on stigma research and global health, which was organized by the Fogarty International Center, National Institute of Health, United States. The article was supported by a generous contribution by the Fogarty International Center.

Funding

The publication of this paper was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health. Anne Stangl and Iman Barré received support for writing from the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation (2016-4379) and the STRIVE research program consortium funded by UK Aid from the Department for International Development. Valerie Earnshaw received support for writing from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K01DA042881). Carmen Logie received support for writing from an Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation Early Researcher Award and the Canadian Foundation for Innovation. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the funding agencies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS, VE, CL, WvB, LS, and JD conceptualized the manuscript. AS led the manuscript writing. VE, CL, WvB, LS, IB, and JD were involved in drafting the manuscript and provided critical feedback on the framework and full manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Stangl, A.L., Earnshaw, V.A., Logie, C.H. et al. The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: a global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med 17, 31 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1271-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1271-3