Abstract

Peers can positively or negatively influence situations where nudes are forwarded without the original sender’s consent. This study aims to explore opinions and representations of adolescents regarding bystanders’ reactions to nudes being forwarded without consent. Discussions through focus groups (FG) were facilitated with vignettes using quotes related to bystanders. While discussions revolved around the quotes, acting as scenarios, most participants referred to personal experiences as most knew such situations in their social circles. Between May and June 2021, 42 adolescents (23 females) aged between 14 and 17 years participated in eight online FG. A thematic content analysis was performed. Participants reported different levels of bystanders’ responsibility depending on whether one does nothing, reacts by laughing or insulting, or continues to share, this last action being, for most, the most serious one. Several active behaviors were mentioned: shunning the victim, gossiping, laughing, mocking, insulting, and prolonging the sharing. Peer pressure, fear of retaliation, emotional management, friendships, age, and gender were explanations for the different bystanders’ behaviors. There is a lack of awareness of peers’ responsibility regarding nudes being forwarded without consent. It is essential to include bystanders in prevention strategies to make them aware of their influential role within the social dynamic. Demonstrating the weight that the group, collectively, can have in such situations could encourage bystanders to play a proactive role, fostering a sense of responsibility and empowerment. Deconstructing gender stereotypes from an early age is crucial to reduce violence related to power imbalances, discrimination, or expectations associated with gender roles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nudes is the term used to define personal sexual-related pictures electronically shared between two persons (Needham, 2021). In addition to pressure issues to obtain such content, nudes are sometimes forwarded to third parties without the consent of the depicted person (Celizic, 2009; Clancy et al., 2019; Madigan et al., 2018; Wolak & Finkelhor, 2011). The prevalence of non-consensual forwarding among youth ranges from 8 to 20% (Barrense-Dias et al., 2020; Madigan et al., 2018; The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, 2008). Some authors consider non-consensual forwarding in a bullying perspective with characteristics common to both issues such as power imbalance between victims and perpetrators and group pressure (Finkelhor et al., 2021; Ojeda et al., 2019).

As bystanders, peers can positively or negatively influence a situation by, for example, reporting the forwarding to adults or supporting the victim or, on the contrary, through participating to and reinforcing the bullying (DeSmet et al., 2019; Harder, 2021; Salmivalli, 2010; Salmivalli et al., 2011). Even one peer’s passivity could worsen the problem (Pozzoli et al., 2012). Four distinct roles of people witnessing bullying situations can be distinguished: assistant who is joining in the bullying, reinforcer who is giving positive feedback without being active, outsider who is staying away, and defender who is comforting and supporting the victim (Salmivalli, 1999). In a recent Belgian study, 72% of adolescents reported no reaction when they received a forwarded nude while 8% admitted having showed or forwarded it to someone else (Van Ouytsel et al., 2021). Some bystanders’ reactions may be related to a lack of empathy, but also to insecurity, including the fear of being victimized in turn (Allison & Bussey, 2016; Schacter et al., 2016).

Females and males would be equally likely to witness a non-consensual forwarded nude and to forward it as third parties (Flynn et al., 2022; Van Ouytsel et al., 2021). However, motivations to act in a certain way as a bystander may differ according to gender, just as motivations to share without consent can. Indeed, one study showed that forwarding a nude without consent was linked to gossiping intent for girls, and to normalizing the practice of sexting for boys (Casas et al., 2019). In the same line, another study found that males were more likely to report showing off as a motive to forward without consent (Barrense-Dias et al., 2020). Another gender specificity was identified in relation to the slut-shaming issue with bystanders’ reactions towards the victim of a non-consensual forwarding being more negative if the victim was a female (Lippman & Campbell, 2014; Ringrose et al., 2012; Van Ouytsel et al., 2014; Walker et al., 2013; Walrave et al., 2015).

Several authors advocated for not only including the potential victim and the perpetrator in bullying prevention measures but also peers or, in other words, potential bystanders to increase solidarity and strengthen empathy (Harder, 2021; Schacter et al., 2016; Walker et al., 2013; Walrave et al., 2015). In addition, peer responsibility in relation to forwarded nudes would not be so clear to young people (Clancy et al., 2019; Walker et al., 2013; Walrave et al., 2015). Perhaps this is due to the absence of this actor in most prevention campaigns. Indeed, social or group dynamics, which can lead to deleterious reactions towards the victim, are rarely considered in nudes-related prevention, mainly focusing on potential victims (Barrense-Dias et al., 2018).

In the French-speaking part of Switzerland, the approach adopted in recent years to prevent peer-to-peer bullying in school context is the non-blaming shared concern method (Pikas, 2002). This method is designed to involve not only the victim and the bully but also the larger peer group in addressing bullying situations. More precisely, during interviews conducted by an adult trained in the method, participants are encouraged to share their perspectives, feelings, and concerns related to the bullying situation, with a focus on problem-solving. Thus, those interviewed are actively encouraged to contribute to finding solutions to the problem, adopting a collaborative approach that aims to empower peers to play a proactive role in creating a supportive and respectful social environment, while promoting empathy. The approach is consistent with a broader recognition of the significance of addressing the social dynamics associated with bullying (Harder, 2021; Salmivalli et al., 1996). As overcoming peer pressure during adolescence might be a real barrier, some authors suggest working on moral engagement or reasoning of young people to avoid harmful bystanders’ reaction (Gini et al., 2015; Song & Oh, 2018).

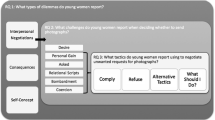

A significant research gap exists concerning the role of bystanders and group dynamics in the context of non-consensual forwarding of explicit content (Mainwaring et al., 2024), particularly among minors. This is especially relevant as adolescents may be driven by a higher desire for conformity and “normality” during their exploration and experimentation in relationships and intimacy. In this line, and in order to better understand the roles of peers when a nude is forwarded without consent, this study aims to explore opinions and representations of adolescents regarding bystanders’ reactions to such a situation.

Methods

Participants

Between May and June 2021, 42 adolescents (23 females) aged between 14 and 17 years (median 16) participated in eight focus groups (FG), which lasted approximately1 h. Given the sensitive topic of this study, we decided to see females and males separately. In addition, gender homogeneity is often recommended for FG with youth, avoiding an adaptation of the speeches or embarrassment and encouraging discussions thanks to this common characteristic. No one from another gender category than females or males contacted us.

Procedure

We conducted this exploratory qualitative research in the canton of Vaud (French-speaking part of Switzerland) using FG. This method allows to capture the meaning that can be given to a social phenomenon and to deepen the interpretations and perceptions of participants (Flick, 2018; Heary & Hennessy, 2002). This technique also offers a space for interaction between participants and a climate of safety and trust during the discussion, which is particularly beneficial for adolescents who have to discuss sensitive topics (Frith, 2000; Hyde et al., 2005).

An ad calling for adolescents aged 14–17 who were interested in giving their opinion on the role of bystanders in sexting context was posted in a job recruitment website for youths aged 15–22 and on the social network of a prevention association and sent to several regional community centers. We indicated that we aimed to collect general points of view and not personal experiences. The snowball method was also used. Participants had to reach us through phone, e-mail, SMS, or instant message, and we asked them their age, gender, and availability. We stopped recruiting when we reached data saturation or informational redundancy regarding the emergence of additional insights or the main themes that we aimed to address (Saunders et al., 2018).

FG were conducted by videoconference using the secure professional version of the Zoom© platform due to the sanitary measures imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Prior to each meeting, participants received a link to an online questionnaire to answer some sociodemographic questions (gender, age, current main occupation). The platform also included an information letter explaining the study and the rules of confidentiality, as well as an electronic participation consent form to sign. The link for the discussion was sent a few hours before the appointment. Before starting, the important points included in the information sheet were verbally recalled. Discussions were audio-recorded (with a voice recorder not through the Zoom© platform), anonymously transcribed verbatim, and then deleted. To ensure anonymity, all identification elements were removed during transcription. Each participant received an electronic gift card approximately 30 US$ for a store.

The Cantonal Ethics Committee verified the protocol and gave a waiver as it did not need to be evaluated according to Swiss law. According to the Federal Act on Research involving Human Beings, discussions could be carried out without the informed parental consent as participants were at least 14 years old and risks of the study were minimal. Contacts for help institutions were included in the information letter. A participant who had reported personal difficulties could have been referred to these institutions. None of the participants directly reported any problems during these discussions.

Discussions were initiated with questions about what sexting was in general and how the practice could sometimes go wrong (e.g., What is sexting? What are the risks of sexting? How do you explain that sometimes sexting goes wrong? Are there any gender differences?). Subsequently, vignettes using bystanders’ perspectives were used to focus on these actors and facilitated the discussions. The vignettes came from previous qualitative studies (blinded reference) on sexting using quotes from adolescents aged between 13 and 19 years old. Different situations were presented: (1) discussion on the difference between verbal and physical violence; (2) quote on gossip intent; and (3) quote on responsibility issues. The discussions revolved around the quotes, acting as hypothetical scenarios, but also on personal experiences, as most of participants having already been aware of such issues in their social circles. Based on the quotes, we asked them their first reactions after reading them and how they designated and defined the persons who were talking (bystanders). We asked them how they perceive the role of bystanders when a non-consensual nude is forwarded. We followed with questions on the different behaviors a bystander might adopt (e.g., How might a bystander react to an image being forwarded without consent? Do you perceive any gender differences in these reactions?) and why (e.g., as a prompt How do you explain that some youth do nothing?).

Data Analysis

We performed a thematic content analysis, a method for identifying and reporting patterns, extracting subjective interpretations and meanings using a process of organization, classification, and categorisation of the data (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). A computer-assisted analysis was carried out using MAXQDA (v22.1.1). Some codes or themes were developed a priori with the interview grid based on literature, mostly the main themes (definitions of bystander and accomplice, responsibility, potential bystander reactions, and explanations of reactions), and others, principally subthemes, were then developed through the analyses and derived directly from the data.

Two discussions were double-coded by the first and last authors, and the coded transcripts were then compared for agreement. The final codebook was applied to all the transcripts by the first author and crosschecked by the other authors. Each new code or doubt was discussed between the authors. This process allowed for a form of triangulation at the level of the analysis, thus avoiding the risk of bias as much as possible. Quotes were translated from French into English.

Results

Based on the interview grid, four main themes were discussed: definitions of a bystander, bystanders’ responsibility, potential bystanders’ reactions, and factors explaining the reactions. The subthemes are developed within each section.

Definitions of a “Bystander”

Bystander

First, participants were asked to define what a bystander is in such a context. For some participants, a bystander was a person who saw a situation but did not react. Hearing a story would be enough to be considered as a bystander. “For me, the place of bystander […] it’s when you just hear a story.” (Female, 17Footnote 1). Specifically with a nude, a person who received an unsolicited intimate picture and did nothing could be defined as a bystander. “For me, a bystander is someone who has seen it (the picture) but who does not talk about it […]” (Male, 17). The status of bystander would therefore depend on whether or not the person was aware of a problem.

Accomplice

There would be a distinction between those who knowing something did not react, the bystanders as defined previously, and those who would react in a negative way, becoming perpetrators. “For me, the one who shares is a witness, but I think he becomes the stalker. He adds to it (the problem) instead of shutting up. […] He/She moves on to another stage.” (Male, 17). Finally, a real bystander would be someone who knows the problem and tries to help. All other reactions, even the fact of doing nothing, would transform a bystander into an accomplice. “We are all bystanders if we know, and then it depends on how we act. For example, if we share it (the picture), we go from being a witness to being an accomplice, and if we let it happen, we remain a witness but we also remain an accomplice. And then you can be a real witness by trying to help the person or make it stop […].” (Female, 15).

Responsibility

Lack of Awareness

First of all, some participants reported a lack of awareness of peer responsibility regarding these issues. “Maybe they don’t necessarily realize the damage they can do or how the person can feel.” (Male, 16). This would allow some to disclaim responsibility for their action, especially when the picture has already been shared, thinking that one more time would not change anything. “[…] The fact is that if the picture has already been shared, then you feel irresponsible and […] you don’t have any trouble sending it again because you say to yourself ‘Anyway, everyone has it so it’s no big deal!’ […].” (Male, 17).

Level of Responsibility in Terms of Behaviors

Then, there would be different stages of responsibility depending on whether one does nothing, reacts by laughing or insulting, or continues to share, this last action being, for most, the most serious one.

First, opinions were divided about those who were aware of a problem but did nothing. For some, doing nothing would already be part of the responsibility for not solving the problem. “I said that if the person does not react, he or she is guilty […]. This person could have done something to help this other person […].” (Female, 16). While, for others, a person would not be liable as long as they did not share the content. “For me, as long as you don’t share it, you’re not guilty […].” (Female, 17).

The most serious reaction, and the one that would incur the most responsibility, is to share. Regarding this action of sharing, the participants made several distinctions. First, there were discussions about the difference in responsibility between sharing by sending or sharing by showing on your phone. “Well I think it depends on when you want to show someone like ‘Oh look, I know bla bla…’, it’s indirectly. Completely directly, it’s when you share.” (Female, 16). Opinions were mixed with participants thinking that showing would be less serious. “I find that sharing on WhatsApp or like that, it stays, whereas (showing) on a phone, it’s seen once and then it’s over.” (Male, 16). While for others, both actions would incur the same responsibility given the effect that could occur, including massive sharing and rumors. “But it’s still serious because depending on our reaction, we can motivate the person (who shows the content). If we laugh, it will encourage the person who showed it to us to share it even more […].” (Male, 17).

Level of Responsibility in Terms of Chain Link

Second, some participants distinguished between the first person who shares and subsequent senders, considering the latter to be less responsible. “Yes it is sure that the one who shares the photo first […], this is in the most serious. And then, I would say that it’s those who continue to share.” (Female, 17). However, for the majority of participants, the responsibility was equal. “[…] All those who share, it does not change anything. For me, they all have the same degree of fault; ‘it (the picture) has been shared all over the place so I’m going to share it even more’. It doesn’t make sense, whether it’s about nudes or anything else.” (Female, 15). In this line, responsibility of third parties would be as important as the one incurred with the first sharing as without them, the problem would not even exist. “[…] If there was just one person who published the photos and there was nothing behind them that would change everything.” (Female, 17).

Potential Bystander Reactions

In relation to how a bystander could react to a non-consensual sharing of intimate pictures, participants mentioned different passive and active behaviors ranging from doing nothing to prolonging the sharing and participating to the bullying.

Doing Nothing

First, doing and saying nothing was reported as a way of not being involved in the problem. “[…] Someone who […] does not talk about it (a picture); […] because he/she does not […] want to be involved in it […].” (Male, 17). Or not knowing what could be done as a witness. “Honestly, even if we receive them (nudes), it’s complicated to know what to do…” (Female, 17). However, it would seem that doing absolutely nothing would not be really possible because it seemed inevitable that such an event would, at least, be discussed with friends. “Well, we wouldn’t share but I think that… well […] we’d talk about it with friends […], close friends, not in front of everyone but everyone does that I think. To say to your best friend ‘Oh, did you see the picture?’ And that, well, I mean, it’s… inevitable.” (Female, 16).

Deleting the Content

Second, even though several participants were pessimistic about the impact of such an action, participants talked about deleting the picture. “But the problem, […] even when you delete a photo, […] from the moment it starts, it’s very, very hard to stop it […].” (Female, 17). This action was also presented as a way to protect themselves. “[…] I delete it (the picture) from my phone because if there’s a police investigation for harassment or something like that, I obviously don’t want to have the picture on my phone and be involved […].” (Male, 15).

Supporting the Victim

Third, another action being reported was supporting the victim, but it remained in the minority and it was mainly the females who presented this opportunity to act. “They’ll comfort the victim […]. They’re going to say that it’s okay, that she can do what she wants with her body and… yes they’re going to support her because that’s what she needs.” (Female, 15). This support could also be indirect and, therefore, easier to achieve. “[…] I think that there are ways to support the person even if we don’t talk to her/him directly. Like for example, if it’s in a school setting, talking to the people who work in the school so that they can intervene […].” (Female, 17). Finally, some admitted that they could not resist adopting a sanctimonious discourse towards the victim, with no malicious intent. “To be honest with you, if […] I see a picture of a female, I wouldn’t go as far as insulting her […] just… let’s say lecture her and say ‘Be careful next time!’.” (Male, 15).

Bullying the Victim

Fourth, several steps in the bullying of the victim were mentioned: shunning the victim, gossiping, laughing and mocking, insulting, and prolonging the sharing.

The shunning of the victim would be due to the negative opinion that others would have of this person with regard to sexting practice. “I would say that the reaction is often that the person will automatically be put aside because people will have a negative image of the person whose pictures are being shared and so when they see the picture, they will not necessarily say anything but they will automatically put the person aside.” (Male, 17). There was also a lot of discussion about rumors and gossips, which turned out to be a big concern for adolescents. “I sincerely think the worst thing are the rumors because it goes very very fast and after a while there are several schools that know and it’s hard.” (Female, 17). Laughing and mocking could be directly related to the victim’s body. “[…] It was a friend who sent it to me saying like ‘Oh look! She has no ass!’ or something silly like that but it was in that sense I mean… just kidding!” (Female, 15). The term “whore” or “bitch” or “slut” was very often used to describe the insults, obviously towards females exclusively. “When it’s a female, […] it’s easily a whore, a slut because she sent pictures […].” (Female, 16). Besides the gender difference in the individuals targeted by the insults, with females being more frequently victims, a higher representation of females among the perpetrators of the insults was also reported. This could be explained by the fact that females already criticize each other a lot for other reasons. Moreover, it seems that this kind of reactions would last much longer among females than males. “They (males) talk about it for two minutes and then they talk about another subject, whereas the females, […] they’ll stay on it and so they’ll look at it (the picture), they’ll judge it a bit more. In the long term, it will last longer than with males.” (Male, 17). Finally, the last reaction mentioned was to continue sharing as a third party, which was considered as the most serious action for most participants. “[…] There are people who react and then they share to other people saying ‘Look what she is doing!’ […].” (Female, 15).

Explanatory Factors

Different factors to explain the diverse reactions emerged in the discussions: peer pressure or group dynamics, age and maturity issues, relationship and degree of friendship with the victim, or emotion generated by the picture.

Peer Pressure or Group Dynamics

Some youth would simply follow the reactions of the majority. Fear of retaliation was also reported, mainly by females. “I’d like to go and help but […] it could turn against me, I don’t want to be in trouble, I don’t want to be insulted so I stay there and watch […].” (Female, 15). Some people, mainly females, might also react negatively to the victim to show the group that nudes are not part of their practice. “[…] Maybe to clear their name. Often, sharing is for saying “No, but I don’t do that (sending nudes of herself)!” (Female, 15). Laughing with others or making others laugh would also be a reason to talk about a picture, show it, or share it. “[…] Three or four years ago… I would have surely sent it (the nude) to my best friend. ‘Look, it’s too funny!’; it seems to me quite obvious […].” (Male, 17).

Age and Maturity Issues

Negative reactions are more likely to be found among younger adolescents who are more impressionable and less understanding of the practice of sexting. “In my opinion, the younger you are, the greater the group effect is because you grow up, […] you learn things and you mature, so you have much less need to be the same as everyone else […].” (Female, 16).

Degree of Friendship with the Victim

Not participating in violence or bullying and showing support to a victim would also depend on the degree of friendship. Indeed, it would be easier for a friend to take a stand against the group than for a simple acquaintance or a stranger. “[...] If it’s an acquaintance, it’s harder to get involved publicly because people will wonder […] why he defended him/her […] whereas if’it’s […] your best friend […] to whom it happens […], people will say to themselves that it is logical that he intervenes […].” (Male, 17). Similarly, revenge and jealousy were mentioned as possible explanations for negative reactions, especially among females. “[…] I think it’s also a lot of revenge. Well, personally, I know a story […]. There were two females who were friends, well best friends, and then they were no longer friends and in fact, what is really disgusting is that her friend sent worse than a nude; it was really a sex tape to her mother […].” (Female, 17).

Emotions Generated by the Picture

Finally, certain emotions, such as shock or disgust, generated by the viewing of the nude could lead to negative reactions. “Maybe, it’s also […] a way of reacting given that you’re getting something that’s not necessarily normal every day […].” (Male, 17).

Discussion

This qualitative study presents the opinions of adolescents regarding bystanders’ reactions to nudes being forwarded without consent and discussions covered definitions and distinctions between witness and accomplice in such a situation, collective responsibility, and passive and active behaviors as a peer. The status of witness would depend on whether or not the person was aware of the problem. There would be a distinction between those who would try to help the victim of forwarding, and would therefore remain witnesses, and those who would do nothing or continue to share, who would no longer be witnesses but accomplices. Some young people reported a lack of awareness, or knowledge, of peers’ responsibility in such situations. The participants reported several possible (in)actions by peers towards a sexual-related content of someone else shared in a non-consensual manner: doing nothing, trying to delete the content, supporting the victim, and bullying the victim. Several reasons were given to explain these reactions such as direct or indirect influence of the group, aiming to make people laugh, reacting out of revenge and/or jealousy, young age and maturity, closeness and friendship with the perpetrator and/or victim, the shock of seeing the content, or beauty standards. In terms of what a bystander could feel, participants mentioned embarrassment, surprise, disgust, and feeling bad.

As previously reported, participants reported a lack of awareness among youth on peer responsibility in relation to forwarded nudes (Clancy et al., 2019; Walker et al., 2013; Walrave et al., 2015). Yet participants were rather adamant about the definitions of bystanders considering that they could even become accomplices in certain situations. However, some youth would use strategies to maintain distance from an action, minimize its impact, or relieve oneself of guilt, especially when other peers also react (e.g., when the image has already been forwarded). Mainwaring et al. (2024) used the term diffusion of responsibility in this line. In addition, some participants were quite pessimistic about positive actions, such as supporting the victim, to resolve problems linked to a forwarded nude. As in Bennett et al. (2014), some participants reported that they do not have enough skills to intervene. Gossips were also discussed when doing nothing was mentioned by the participants as no reaction at all was considered as being mission impossible when receiving such a nude, highlighting the fact that even if youth consider doing nothing or wish to remain passive when faced with such an image, there will be consequences for the victim.

The difference between forwarding and showing was not always clear in our study, with some youth accepting more the fact of showing without sending the content in terms of bystanders’ responsibility. Indeed, opinions were divided on bystanders’ guilt as, for some, someone who would show a picture directly on the screen phone would be less responsible than someone who would send it, the latter action being unanimously considered as the most serious ones. While studies showed that males and females can equally witness forwarded nudes (Flynn et al., 2022; Van Ouytsel et al., 2021), we were able to identify gender differences in terms of reaction, with females sometimes reacting more negatively, especially when the victim of the non-consensual forwarding was a female. This was particularly the case with the action of shunning someone. These reactions may also be related to the fear of being assimilated to that person and that others will believe they are sending nudes of themselves. This fear can be seen as part of the slut-shaming and cybersexism issues that are also present in the context of sexting (Lippman & Campbell, 2014; Ringrose et al., 2012; Van Ouytsel et al., 2014; Walker et al., 2013; Walrave et al., 2015). In the same line, bystanders who have stereotyped beliefs in regard to sexual violence and rape are less likely to help a victim.

Our study demonstrated the important influence of the group on the reactions of young people as bystanders to a forwarded nude. In adolescence, peers become the main resource and acceptance by the group is therefore essential. In this line, fear of retaliation might explain some bystanders’ behaviors (Forsberg et al., 2018; Strindberg et al., 2020). As previously found (Mainwaring et al., 2024), the fact of feeling safe or not may influence bystanders’ reaction, and those who are afraid of becoming a target if they intervene will not take sides. The fear of being out of the group would even be the main concern of young people (Strindberg et al., 2020). As another explanation, we also identified whether or not adolescents knew the victim of the forwarded nude, specifically whether or not they were friends with her/him. In contrast to a study (Mainwaring et al., 2024) which showed that some participants stressed the importance of helping the victim independently of their relationship, we found that bystanders’ reaction would depend on the friendship with the victim. Moreover, risk of retaliation would be perceived as lower if a bystander opposes the group for a friend. However, the other study (Mainwaring et al., 2024) included adults with a mean age of 23 (age range 18–53), and morality may have taken over with age.

Finally, the practice of sexting could present an ambivalence in terms of emotions mixing excitement and disgust among youth (Macdowall et al., 2022). Receiving a forwarded nude as a bystander could be unsolicited, making it more difficult to manage emotionally, especially among younger adolescents. This could be in line with the disgust towards sexuality in young adolescents, explained by a lack of maturity and sensitivity to such matters (Borg et al., 2019). In this context, disgust acts as a protective mechanism, helping them navigate and manage certain emotions related to new experiences. The emotions that the reception of a nude could generate and the fact that young adolescents could encounter difficulties in managing them could then explain certain negative reactions as described above.

Strengths and Limitations

Thanks to this study, we were able to explore bystanders’ perspective in a bullying situation related to non-consensual forwarding of nudes, a perspective that is not often considered in research and prevention (Harder, 2021). In addition, our sample consisted of adolescents, period during which sexting-related problems appear to be most prevalent (Ševčíková, 2016; Van Ouytsel et al., 2019). However, some limitations need to be discussed. Firstly, our findings are based on self-report and we cannot assure that there was no social desirability bias in the responses. Nevertheless, as we specified that we were not looking for personal experiences or testimonies, we certainly reduced this bias as participants were able to share their opinions without necessarily revealing their own behaviors or emotions. We also used vignettes to facilitate the discussion and create a context where participants could share their views without feeling constrained by personal experiences and showing that we were looking for general opinions and not personal experiences. Secondly, the snowball method could have the bias of recruiting participants who share the same characteristics and opinions, but few participants were recruited using this method. Thirdly, despite that all participants had heard of a case of bullying or violence related to sexting, not all participants took on the role of direct bystander and experienced all the reactions discussed.

Implications for Practice

The school is an ideal place to make young people aware of the group effect in relation to this type of problem because they have to live in and with a group most of the week. The aim would be to improve their knowledge on the responsibility of each person when a nude is forwarded without consent, avoiding the diffusion of responsibility (Mainwaring et al., 2024). Young people were quite pessimistic about their power and skills to intervene. I would therefore be important to demonstrate to them the weight that the group can have to solve a problem and act positively. It is certain that a nude should not even be forwarded without consent in the first place. Prevention must focus on the perpetrators of these first non-consensual forwarding, but peers must be included as they can positively or negatively influence the situation. Finally, the stigmatization of victims, often exacerbated by gender norms, may contribute to the minimization of certain actions under the excuse that the victim, mostly females, should never have sent her/his own image. Deconstructing gender stereotypes from an early age is therefore essential.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Notes

(Gender, Age).

References

Allison, K. R., & Bussey, K. (2016). Cyber-bystanding in context: A review of the literature on witnesses’ responses to cyberbullying. Children and Youth Services Review, 65, 183–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.03.026

Barrense-Dias, Y., De Puy, J., Romain-Glassey, N., & Suris, J.-C. (2018). La prévention et le sexting: un état des lieux. Lausanne, Institut universitaire de médecine sociale et préventive, (Raisons de santé 285). https://doi.org/10.16908/issn.1660-7104/285

Barrense-Dias, Y., Akre, C., Auderset, D., Leeners, B., Morselli, D., & Surís, J.-C. (2020). Non-consensual sexting: Characteristics and motives of youths who share received-intimate content without consent. Sexual Health, 17(3), 270–278. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH19201

Bennett, S., Banyard, V. L., & Garnhart, L. (2014). To act or not to act, that is the question? Barriers and facilitators of bystander intervention. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(3), 476–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260513505210

Borg, C., Hinzmann, J., Heitmann, J., & de Jong, P. J. (2019). Disgust toward sex-relevant and sex-irrelevant stimuli in pre-, early, and middle adolescence. The Journal of Sex Research, 56(1), 102–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2018.1445694

Casas, J. A., Ojeda, M., Elipe, P., & Del Rey, R. (2019). Exploring which factors contribute to teens’ participation in sexting. Computers in Human Behavior, 100, 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.06.010

Celizic, M. (2009). Her teen committed suicide over 'suicide'. TODAY.com. Retrieved Juillet 30 from https://www.today.com/parents/her-teen-committed-suicide-over-sexting-2D80555048

Clancy, E. M., Klettke, B., & Hallford, D. J. (2019). The dark side of sexting – Factors predicting the dissemination of sexts. Computers in Human Behavior, 92, 266–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.11.023

DeSmet, A., De Bourdeaudhuij, I., Walrave, M., & Vandebosch, H. (2019). Associations between bystander reactions to cyberbullying and victims’ emotional experiences and mental health. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 22(10), 648–656. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0031

Finkelhor, D., Walsh, K., Jones, L., Mitchell, K., & Collier, A. (2021). Youth internet safety education: Aligning programs with the evidence base. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 22(5), 1233–1247. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838020916257

Flick, U. (2018). An introduction to qualitative research: 6th Edition. Sage Publications Limited.

Flynn, A., Cama, E., & Scott, A. J. (2022). Preventing image-based abuse in Australia: The role of bystanders. Australian Institute of Criminology.

Forsberg, C., Wood, L., Smith, J., Varjas, K., Meyers, J., Jungert, T., & Thornberg, R. (2018). Students’ views of factors affecting their bystander behaviors in response to school bullying: A cross-collaborative conceptual qualitative analysis. Research Papers in Education, 33(1), 127–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2016.1271001

Frith, H. (2000). Focusing on sex: Using focus groups in sex research. Sexualities, 3(3), 275–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/136346000003003001

Gini, G., Pozzoli, T., & Bussey, K. (2015). The role of individual and collective moral disengagement in peer aggression and bystanding: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(3), 441–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9920-7

Harder, S. K. (2021). The emotional bystander – Sexting and image-based sexual abuse among young adults. Journal of Youth Studies, 24(5), 655–669. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2020.1757631

Heary, C. M., & Hennessy, E. (2002). The use of focus group interviews in pediatric health care research. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 27(1), 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.47

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Hyde, A., Howlett, E., Brady, D., & Drennan, J. (2005). The focus group method: Insights from focus group interviews on sexual health with adolescents. Social Science & Medicine, 61(12), 2588–2599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.040

Lippman, J. R., & Campbell, S. W. (2014). Damned if you do, damned if you don’t…if you’re a girl: Relational and normative contexts of adolescent sexting in the United States. Journal of Children and Media, 8(4), 371–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2014.923009

Macdowall, W. G., Reid, D. S., Lewis, R., Bosó Pérez, R., Mitchell, K. R., Maxwell, K. J., Smith, C., Attwood, F., Gibbs, J., Hogan, B., Mercer, C. H., Sonnenberg, P., & Bonell, C. (2022). Sexting among British adults: A qualitative analysis of sexting as emotion work governed by ‘feeling rules.’ Culture, Health & Sexuality, 25(5), 617–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2022.2080866

Madigan, S., Ly, A., Rash, C. L., Van Ouytsel, J., & Temple, J. R. (2018). Prevalence of multiple forms of sexting behavior among youth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(4), 327–335. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.5314

Mainwaring, C., Scott, A. J., & Gabbert, F. (2024). Facilitators and barriers of bystander intervention intent in image-based sexual abuse contexts: A focus group study with a university sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605231222452

Needham, J. (2021). Sending nudes: Intent and risk associated with ‘sexting’ as understood by gay adolescent boys. Sexuality & Culture, 25(2), 396–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09775-9

Ojeda, M., Del Rey, R., & Hunter, S. C. (2019). Longitudinal relationships between sexting and involvement in both bullying and cyberbullying. Journal of Adolescence, 77, 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.10.003

Pikas, A. (2002). New developments of the shared concern method. School Psychology International, 23(3), 307–326.

Pozzoli, T., Gini, G., & Vieno, A. (2012). The role of individual correlates and class norms in defending and passive bystanding behavior in bullying: A multilevel analysis. Child Development, 83(6), 1917–1931. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01831.x

Ringrose, J., Gill, R., Livingstone, S., & Harvey, L. (2012). A qualitative study of children, young people and ‘sexting’: A report prepared for the NSPCC. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/44216/

Salmivalli, C., Lagerspetz, K., Björkqvist, K., Österman, K., & Kaukiainen, A. (1996). Bullying as a group process: Participant roles and their relations to social status within the group. Aggressive Behavior, 22(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(1996)22:1<1::AID-AB1>3.0.CO;2-T

Salmivalli, C. (1999). Participant role approach to school bullying: Implications for interventions. Journal of Adolescence, 22(4), 453–459. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.1999.0239

Salmivalli, C. (2010). Bullying and the peer group: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15(2), 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.08.007

Salmivalli, C., Voeten, M., & Poskiparta, E. (2011). Bystanders matter: Associations between reinforcing, defending, and the frequency of bullying behavior in classrooms. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40(5), 668–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2011.597090

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), 1893–1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

Schacter, H. L., Greenberg, S., & Juvonen, J. (2016). Who’s to blame? The effects of victim disclosure on bystander reactions to cyberbullying. Computers in Human Behavior, 57, 115–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.018

Ševčíková, A. (2016). Girls’ and boys’ experience with teen sexting in early and late adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 51(1), 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.06.007

Song, J., & Oh, I. (2018). Factors influencing bystanders’ behavioral reactions in cyberbullying situations. Computers in Human Behavior, 78, 273–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.10.008

Strindberg, J., Horton, P., & Thornberg, R. (2020). The fear of being singled out: Pupils’ perspectives on victimisation and bystanding in bullying situations. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 41(7), 942–957. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2020.1789846

The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. (2008). Sex and tech: Results from a survey of teens and young adults. https://www.drvc.org/pdf/protecting_children/sextech_summary.pdf

Van Ouytsel, J., Walrave, M., De Marez, L., Vanhaelewyn, B., & Ponnet, K. (2021). Sexting, pressured sexting and image-based sexual abuse among a weighted-sample of heterosexual and LGB-youth. Computers in Human Behavior, 117, 106630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106630

Van Ouytsel, J., Walrave, M., & Ponnet, K. (2019). An exploratory study of sexting behaviors among heterosexual and sexual minority early adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 65(5), 621–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.06.003

Van Ouytsel, J., Walrave, M., & Van Gool, E. (2014). Sexting: Between thrill and fear—How schools can respond. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 87(5), 204–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.2014.918532

Walker, S., Sanci, L., & Temple-Smith, M. (2013). Sexting: Young women’s and men’s views on its nature and origins. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52(6), 697–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.026

Walrave, M., Ponnet, K., Van Ouytsel, J., Van Gool, E., Heirman, W., & Verbeek, A. (2015). Whether or not to engage in sexting: Explaining adolescent sexting behaviour by applying the prototype willingness model. Telematics and Informatics, 32(4), 796–808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2015.03.008

Wolak, J., & Finkelhor, D. (2011). Sexting: A typology. Durham, NH: Crimes against Children Research Center. https://scholars.unh.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1047&context=ccrc

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Lausanne This study was financed by the Direction Générale de la Santé du canton de Vaud (Directorate General of Health (Canton of Vaud)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yara Barrense-Dias conceptualized and designed the study; obtained funding; collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data; drafted and revised the manuscript; and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Joan-Carles Suris contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, critically revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Lorraine Chok collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data; critically revised the manuscript; and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

The Ethics Committee of the canton of Vaud gave a waiver (req 2021-00034) as it did not need to be evaluated according to Swiss law.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barrense-Dias, Y., Suris, JC. & Chok, L. “Maybe They Don’t Necessarily Realize the Damage They Can Do…”: A Qualitative Study on Bystanders to Non-consensual Forwarding of Nudes Among Adolescents in Switzerland. Int Journal of Bullying Prevention (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-024-00249-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-024-00249-2