Abstract

Bullying and victimization in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a problem of particular importance, as this category of students is at high risk of victimization by other students, which negatively affects their psychosocial and emotional development. The purpose of this study is to investigate the rate of victimization of children with high-functioning autism (AHF) by their peers in primary school, and whether this rate correlates with teachers’ education professionals’ classroom practices for the inclusion. Data collection was conducted using two questionnaires, the Autism Inclusion Questionnaire (AIQ) (Segall & Campbell in Autism inclusion questionnaire, 2007), which explores the educational practices that teachers utilize in terms of including students with ASD in the general classroom (Segall & Campbell in Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 6(3):1156–1167, 2012), and the questionnaire on victimization of children with ASD by their peers (Belidou in Autism spectrum disorder and victimization: teachers’ views of the association with theory of mind and friendship (Master thesis), 2017). The survey was based on the responses of 143 teachers who teach primary school students diagnosed with high-functioning ASD. The results showed that 34.3% of teachers observed that AHF children are at higher risk of victimization compared to typically developing children. Also, it was found that there are several educational practices of children with autism, which are associated with the victimization of children belonging to the high-functioning autism spectrum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, the international standards of all countries and Greece call for more inclusive school environments. The inclusion classroom of children with high-functioning autism (AHF) in all levels of education is implemented through co-teaching strategies and practices. Co-teaching promotes the inclusion of students with AHF in the same school environment as typically developing students. However, the policy of inclusion is challenging for both HFA students and teachers due to the high risk of victimization of these students (Humphrey & Hebron, 2015). Their victimization compounds their existing social difficulties with adverse effects on their psychosocial and emotional development (Locke et al., 2010). Research on bullying of AHF students is limited, and findings suggest an exacerbation of their victimization phenomena in inclusive school settings (van Schalkwyk et al., 2018). However, research on the victimization of AHF students (van Schalkwyk et al., 2018), prevention strategies, and coping methods are very limited, while all studies focus on prevention through interventions to address depression, anxiety, and suicidality (Ung, 2016). Also, there is limited research data on the victimization of the same group of students by typically developing peers in primary school, which makes it difficult to draw safe conclusions (Chou et al., 2019; Hu et al., 2019). Furthermore, no literature was found that focused on the co-teaching of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and the impact of general and special education teachers’ practices on the exacerbation of bullying victimization phenomena among ASD students.

Educational practices implemented in the classroom mobilize factors that influence the inclusion or not of autistic students in general education. In particular, co-teacher training has been found to be associated with more positive attitudes toward inclusion (Segall, 2012). Subsequently, the implementation of specific strategies based on certain educational practices can support inclusion (Bond et al., 2017). In addition, current literature highlights the need for specific training for teachers of HFA students as through this, it is possible to increase their self-efficacy, which contributes to a change in their attitudes and promotes inclusion (Russell et al., 2022). Based on the above, the present research aims to investigate which educational practices of co-education and inclusion promote or discourage the manifestation of victimization of students with HFA by their typically developing peers in primary school.

Literature Review

Bullying in Autism High-Functioning Children

Bullying is a major problem in school life. In this problematic school context, students with ASD are overrepresented as victims. Their involvement rates depend on the methodology used in the studies (Sreckovic et al., 2014). A meta-analysis suggests that the estimated prevalence of perpetrating bullying, victimization of students with ASD, and simultaneous involvement as perpetrators and victims was 10%, 44%, and 16% respectively (Maïano et al., 2016). Similarly, Chou et al.’s (2020) research data describe the percentages of HFA adolescents who were neutral, net victims, net perpetrators, and victims in victimization incidents as 63.9%, 17.8%, 9.1%, and 9.1%, respectively. A recent survey from the National Transition Analysis Study, which examined rates of bullying victimization in a sample of parents of ASD young people (N = 900), aged 13–16 years, found that 46.3% of young people reported bullying victimization (Sterzing et al., 2012). At the same time, the intensity of bullying toward ASD students is worth noting. More specifically, in a sample of 192 parents of youth with ASD, aged 5–21 years, 54% of responding parents reported that bullying victimization persisted for more than 1 year (Cappadocia et al., 2012). In another study involving 101 mothers of ASD youth, (aged 12–21 years), 36% reported that their children experienced bullying two or more times per week (Weiss et al., 2015).

It is noteworthy that, given the high prevalence of the phenomenon of victimization of ASD students in the school setting, the recent research literature has focused on studying the factors that make the group of ASD students vulnerable to victimization (Kerns et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2021; Pabian et al., 2016). Relatively speaking, therefore, the studies agree that there is a psychological burden on the victimized. With absolute accuracy, it is confirmed that pure victims had more severe depression and anxiety compared to self-reported neutral, perpetrator-victims (Chou et al., 2020). The increased victimization of high-functioning ADHD children is attributed to their deficient understanding of social behavior cues compared to typically developing children. This was found in a study that investigated their ability to understand bullying in valid video clips containing actual bullying situations as well as staged bullying situations (Hodgins et al., 2020). Therefore, the new findings suggest that ASD adolescents understand bullying differently than their typically developing peers. This difficulty may explain problems in interpreting their involvement in bullying incidents.

There is limited research data on bullying and victimization of HFA children in the school setting. This is in part because the studies that have been conducted involved students diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders in general, which includes HFA students. In particular, one study which looked at the victimization rate of children with ASD was based on the views of 97 Greek teachers who have taught children with ASD in the school setting, with 45.4% of the sample of teachers having been exclusively responsible for teaching HFA children (Belidou, 2017). The results obtained from the observations of the Greek teachers show that 38.1% of the teachers observed that students with ASD are vulnerable to victimization in the school setting. It is noteworthy that victimization occurs mainly in an indirect form, which is manifested by excluding children from activities and isolating them from groups (25.8%). Less frequently, victimization occurs in direct forms, such as physical or verbal abuse (15.5% and 8.2% respectively). Similar are the findings of Kloosterman et al. (2013) on the victimization of HFA students, aged 11–18 years. Therefore, HFA students are primarily victimized by social isolation, more than typically developing students, and subsequently by physical and verbal forms of bullying.

Factors Associated with the Victimization of Autism High-Functioning People

In reviewing the literature, it was found that research regarding the factors that are significantly associated with the phenomenon of special-category victimization of HFA students is quite limited. This is because a large number of researchers study the phenomenon of victimization in the totality of autism spectrum disorders, including all subcategories (Liu et al., 2021). Researchers Chou et al. (2019) focused only on the specific category of HFA students and argue that there are certain factors associated with the psychopathological characteristics of HFA children, which make these individuals particularly vulnerable victimization in the school setting. The focus is on the weakness of social and communication skills, which weakens their ability to develop social interactions. The results of this study, based on self-reports from students with ASD, as well as their parents, show that the percentage of students who have been victims of bullying have more severe deficits in social communication. Difficulties in social communication and social interaction are diagnostic criteria for one of the two high-functioning behavioral domains of individuals as listed in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5/APA, 2013). Social communication deficits may also limit the ability of individuals with ASD to form friendships with others, reducing the likelihood that they will receive protection and help from others when bullied (Rowley et al., 2012a, b). Research evidence from other studies suggests that victimization does not correlate with social awareness and social emotion. In the same vein, research by Chou et al. (2019, 2020) demonstrates that social anxiety was significantly associated with higher rates of bullying in HFA students.

In addition, the comorbidities of HFA are a key factor influencing and contributing to victimization. When victimized, HFA students were more likely to have ADHD (Chou et al., 2019). Furthermore, in the same group of students, emotion regulation problems and affective disorders have been linked to high rates of victimization (Zablotsky et al., 2014).

Educational Practices and Inclusion of pupils with Autism

The success of an inclusion program in mainstream schools is influenced by the choice of teaching approaches, the educational practices that teachers use for students with ASD, and the effectiveness of those interventions (Cassady, 2011; De Boer et al., 2011; Sam et al., 2021). Knowledge of educational practices is a particularly important factor in the successful inclusion of ASD children in the general education school environment (Jordan, 2005). Overall, these practices are numerous and varied. They include changes in the physical classroom environment, teacher-related variables and interventions involving social skills. In the field of autism, there are key interventions and treatments which have the potential to be considered as a basis for formulating of successful educational programs for students with ASD. Ultimately, effective practices are those that are systematically and objectively tested, accurately applied, and adapted to the specific needs of the students (Simpson, 2005). Simpson et al. (2005) evaluated 35 interventions and treatments (Table 2) used for children and young people with ASD and organized the methods into five categories: basic skills, interpersonal, cognitive, psychological/biological, neurological, and other. The 35 interventions and treatments are categorized (Simpson, 2005) into four groups:

-

(a)

Scientifically based practices were identified as those with significant and proven empirical effectiveness and support.

-

(b)

Promising practices that, although they were effective for pupils with ASD, needed further objective evidence.

-

(c)

Practices with limited support, which lacked objective and convincing/supporting evidence but had potential usefulness and effectiveness.

-

(d)

Non-proposed practices which lacked effectiveness and whose use could even be harmful.

The Autism Inclusion Questionnaire (Segall & Campbell, 2007), which will be utilized for the purposes of this study, includes 38 interventions, of which 14 interventions are included in the list of practices that are part of the twenty-seven (27) documented practices according to the National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorder (NPDC/2014) (Kucharczyk et al., 2012). However, including the interventions in Table 1, the practices included in this questionnaire can be classified by the skills that they aim to cultivate or by area of focus as follows (Simpson, 2005):

-

Basic skills: applied behavioral analysis, teaching key skills, assistive technology, augmentative and alternative communication, instruction by occasion, common action routines, structured teaching (TEACCH Method), Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS), training by discrete trials, communication facilitation, and the Van Dijk Thematic Approach

-

Interpersonal relations: strategies adapted to play, play on the floor, practice teaching, and intervention through relationship development

-

Cognitive: social stories

-

Psychological/biological, neurological: sensory integration

-

Classroom modifications: position by preference, relaxation strategies, providing a list of changes to the school schedule for a school day, and providing a list of expected behaviors in the classroom

-

Social skills: direct teaching of social skills, teaching typically developing pupils about ASD, peer initiation, and inter-peer teaching

-

Teaching techniques: extra time to complete tasks, preparation strategies, motivation strategies (e.g., verbal, visual, imitation, and physical), and visual activity schedule

-

Behavior management: behavior contract, decision-making, food support, functional behavioral assessment/analysis, reward exchange system, verbal reinforcement-praise, and differential reinforcement of alternative, opposite, or other behavior

-

Others: therapy through art

Method

Purpose

The present study aims to investigate the rate of peer victimization of HFA students in primary school and whether this rate correlates with teachers’ educational practices in the context of inclusion. More specifically, the aim was to answer two exploratory questions: (1) What is the rate of victimization of HFA children by their peers in primary school? (2) Is there a correlation between the rate of victimization of children with ASD and professional, educational practices in the context of inclusive co-teaching?

Population

Τhe population examined in this study is 143 primary school teachers in four regions of Greece, Achaia, Ioannina, Kozani, and Aitoloakarnania. The teachers invited to participate in the study were teaching in the current school year 2022–2023 in general education primary schools and working with HFA students. They aimed to promote inclusion and integration in general education schools.

Measures

Data collection was based on a single questionnaire, which was the result of the synthesis of two valid questionnaires. The questionnaire used is titled “Teachers’ Questionnaire -on the topic: correlation between applied, educational practices toward HFA students and bullying, victimization behaviors” which included closed-ended questions graded on the Likert scale, which were then processed and coded.

More specifically, the first part contains a self-report questionnaire, utilized in the study, the Autism Inclusion Questionnaire (AIQ) (Segall & Campbell, 2007), which was developed to investigate teachers’ experiences, knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding the inclusion of students with ASD in the general classroom at the University of Georgia in the USA. The Autism Inclusion Questionnaire (AIQ) has been utilized by a number of studies, including examining factors related to educational practices for the inclusion of students with ASD in the general classroom (Segall & Campbell, 2012) and factors influencing the choice of school setting for the attendance of students with ASD (Segall & Campbell, 2014). In Greece, it has been utilized in the context of a study by Skipitari (2016), which investigated the experiences and knowledge of general and special education teachers in primary education about autism, their attitudes toward the inclusion of students with autism, and their knowledge and use of strategies in relation to their inclusion in the general classroom of the school. The questionnaire was translated with the authors’ permission. The questionnaire was reviewed by experts in the field of autism, followed by piloting the instrument with teachers with previous experience in general and special education.

The second self-report questionnaire, which explored victimization, friendships between students with ASD and their peers, and deficits according to the theory of mind (Belidou, 2017), was based on previous questionnaires and research data with the same themes, as reported in her research (Goodman & Williams, 2007; Lord et al., 2000; Olweus, 1996; Russell et al., 2022; Solberg & Olweus, 2003; Sofronoff, 2011). The present questionnaire was completed by teachers at all levels who have taught children with autism spectrum disorder in the school setting. It was then tested for reliability, which was quite satisfactory, and implemented.

The single questionnaire in its final form, as utilized for data collection in this study, consisted of four sections. Specifically, the first section included 3 questions with demographic and service information of the teachers in the research sample. The second section consisted of 7 questions that examined the rate of victimization of students diagnosed with high-functioning ASD by their peers and the type of victimization. The third section investigated the friendships of these children with their peers (results not presented in this article). Finally, the fourth section examined the practices used by all teachers during co-teaching to include students with ASD in the general classroom.

Data Collection Process

The process of collecting the empirical material took place during the 2022–2023 school year. In particular, in February 2023, a telephone communication took place with the Education and Counseling Support Centers (ESCs) of Ioannina, Patras, Kozani, and Etoloakarnania in order to approve the request for the distribution of the electronic questionnaires in primary education schools, where HFA children attend. Due to the protection of the personal data of students with ASD, no information was provided to the research team about the personal details of HFA students (gender, age, school, and grade attended). Given these limitations, it was decided to give the questionnaires through the ESCs without direct communication between the research team and the principals or teachers of the schools attended by students with HFA. The application was accepted, in March, and then, the questionnaire was distributed electronically by ESCs to the principals of state, general education, and primary schools through an electronic platform of Google. The principals are committed to forwarding it to the teachers who teach children with ASD in the respective school units. The questionnaires were accompanied by a letter, which provided information about the purpose of the research, their voluntary and anonymous participation, clarifications about the basic conditions, and contact information with the research team. The statistical analysis of the data was carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 22.0.

Results

For the purposes of this research, a descriptive and inductive statistical analysis was performed. First, the results of the elements obtained from the application of the descriptive methods of statistics are presented, and then, the results of the elements of the inductive methods of statistics are presented.

Descriptive Characteristics of the Sample

The total sample consisted of 143 teachers, 94 were women (65.7%), and 49 were men (34.3%). These are teachers who worked in four prefectures of Ioannina, Aitoloakarnania, Patras, and Kozani and serve in general public schools. Subsequently, 33.6% of the sample (N = 48) belonged to the age group of 41 to 50 years, 27.3% (N = 39) belonged to the group of 31–40 years, 34 belonged to the age group of 51–60 years (23.8%), and 22 belonged in the group from 20 to 30 years old (15.4%). Finally, the total percentage of the sample concerns teachers who observed HFA children in the general classroom, parallel support teachers, and specialty teachers. In more detail, of the participants in terms of specialty, 29 were general education teachers (20.3%), 25 were special education teachers (17.5%) who worked in the general public school in parallel support, and 62% were teachers of various specialties who teach English, gymnastics, theater education, music, and informatics (Table 2).

High-Functioning Autism and School Bullying

The results show that teachers who teach in general classes, where HFA children attend, tend to place these children in the vulnerable groups of victimization compared to children with typical development. Specifically, from the responses in Table 3, it appears that 34.3% of the interviewed teachers agree that a child with autism is more vulnerable to victimization than other children. A look at the corresponding table shows that the vast majority (> 60%) agree that children with high-functioning ADHD are vulnerable to victimization (Table 3).

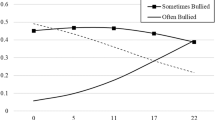

Also, according to the teachers’ statements about individual incidents of bullying in the classroom, it seems that HFA children are mainly bullied once a week (n = 52, p = 36, 4%). The results show that victimization of children with ASD is more intense in the indirect form of excluding children from activities—isolation—and is observed once a week (n = 57, p = 39.9%). Verbal violence is observed mainly once a week (n = 53, p = 37.1%). The direct form of aggression, physical violence against the same category of students, is mainly observed 1 to 2 times in 2 months (n = 48, p = 33.6%). Finally, 30.8% of the teachers state that the abusers spread rumors or lies about the student with ASD mainly 2–3 times per month. 33.6% say that students are forced to do something they do not want to do.

Association of Inclusive Educational Practices with Victimization of Autism High-Functioning Children

The second research question aimed to examine whether the incidents of school bullying victimization of HFA students depend on the inclusive educational practices used by all teachers in the context of co-education. To test the specific research question, the χ2 statistical test was performed. However, in order to investigate the type of correlation, the Spearman correlation coefficient was applied, following the results obtained from the crosstabs procedures (Table 4).

From the results of the x2 test, it emerged that the educational practices of inclusion that are associated with the phenomenon of victimization of children with high-functioning ASD are the following: assistive technology, therapy through art, contract of conduct, decision-making, direct teaching of social skills, extra time to complete tasks, functional behavior assessment/analysis (FBA), pivotal response training (PRT), strategies adapted to the game, motivational strategies (e.g., verbal, visual, imitative, and physical), relationship development intervention (RDI), scenarios (e.g., cognitive scenarios), structured teaching (TEACCH Method), token economies, and verbal reinforcement-praise (Table 5):

Discussion

The present research investigated the phenomenon of school bullying of HFA students in primary school, general education. Use information from the teachers of the specific category of students. In this context, the impact of inclusive educational practices utilized by general and special education teachers working in public schools was investigated.

The obtained results show that the frequency of the phenomenon of school bullying and the victimization of students with high-functioning autism, according to the teachers, is quite high. This conclusion results from the fact that the majority of teachers (> 60%) believe that HFA children are more vulnerable to victimization compared to their classmates. Similar conclusions have been reached by other researchers who have studied in recent research conducted by other researchers, who focused on the victimization of students with HFA (Chou et al., 2020; Van Schalkwyk, 2018). The findings of the present study are consistent with a number of studies that have been conducted, both recently and in the past. The findings support that students on the autistic spectrum, including both those diagnosed with high-functioning ASD and those diagnosed with lower functioning, are more likely to be victimized than typically developing children and also than children with other difficulties (Bitsika & Sharpley, 2021; Chou et al., 2020; Hsiao et al., 2022; Rowley et al., 2012a, b; Zablotsky et al., 2014). It is also worth noting that from the teachers’ statements, the most common form of victimization is exclusion/isolation, followed by verbal and then physical victimization. This finding of the present study is fully consistent with the research data and other studies that show that adolescents with ASD are more often victims of bullying in the form of isolation and exclusion (72%), followed by verbal victimization (66%) (Chiu et al., 2018). Other studies present similar findings which show that children with ASD are more often victims of social isolation, followed by verbal and physical ones, than children with typical development (Locke et al., 2010; Reiter & Lapidot-Leflet, 2007; Wainscot et al., 2008). Prolonged duration and chronicity of victimization is more common in children with ASD in primary and middle school (Blake et al., 2012; Christensen et al., 2012; Rowley et al., 2012a, b). High rates of internalizing problems and conflicts in friendships are significant predictors of peer victimization in children with ASD (Zeedyk et al., 2014). At this point, the need for future research that focuses on strategies that improve the social interaction of the special category of HFA students as a measure to prevent victimization and promote friendships (Rowley et al., 2012a, b) in the general school setting becomes apparent.

In the same direction, the present study investigates which inclusion practices are used by teachers and which correlate positively or negatively with the victimization of HFA students. The statistical analysis revealed several educational practices that are directly related to the victimization of students with ASD (and the friendships that HFA students form with their classmates). This means that the limited use of inclusive educational practices becomes a brake on the development of the communication skills of students with high-functioning ASD. More specifically, one of these practices is art therapy, which belongs to the Limited Support Inclusion Practices. The use of the educational practice “art therapy” is negatively associated with incidents of victimization with HFA students and positively with the friendships formed by HFA students (Gkatsa & Antoniou, 2024). According to the recent research literature, the performing arts (music therapy, dance-motor psychotherapy, theatrical games in therapy), which are included in the wider educational practice of art therapy, play an important role in improving social skills and behavior while contributing significantly to the improvement of social functioning in children with ASD (Aithal et al., 2021; Pater et al., 2021; Schmid et al., 2020). This happens, possibly, because it promotes the reduction of anxiety associated with weaknesses in social skills. It is also pointed out by other scholars as the lack of effectiveness of “educational technology” due to the imprecise design of technological interventions of virtual and augmented virtual reality technology media (Yeung et al., 2021). Some other studies identify serious weaknesses in video game design due to poor integration of non-expert knowledge (Hassan et al., 2021; Malinverni et al., 2017).

Additionally, this research highlighted the following educational practices as important: functional assessment/behavior analysis, key skills teaching, scenarios, and extra time to complete tasks, which belong to evidence-based practices, and the last two in limited support practices. All of these are negatively associated with the victimization of students with ASD. The three aforementioned educational practices have been shown in other research to be quite effective in helping children with ASD acquire a variety of skills in important areas, among which are communication and social interaction (Gutstein, 2009; Koegel & Koegel, 2006; NasoudiGharehBolagh et al., 2013). Therefore, it is understandable that their limited use becomes an obstacle to improving the social skills of students with high-functioning ASD and, consequently, their social interaction with their peers.

In addition, it was found that educational practices such as “Behavior Contract,” “Decision-Making,” and “Adapted Strategies in the game” are negatively related to victimization phenomena. However, there is no literature to support the generalization of any conclusions about the effectiveness of these practices against peer victimization of HFA. However, according to the assumption derived from research data, “Correct Decision-Making” is a deficient skill for children with ASD as the functional abilities of theory of mind and executive function are lacking. The development of the capacity for fair decisions has been documented in research to promote the development of cognitive and executive functions (Jin et al., 2020).

Understanding this becomes increasingly difficult when one considers that students with ASD, because of the disorder in ΤοΜ (Theory of Mind), tend to view a social indication of bullying behavior as “not bad.” Consequently, they underestimate this behavior, fail to make the right decision, and fail to cope with their victimization (Carothers & Taylor, 2004; Steele et al., 2003). Regarding the “adaptation of a strategy in play,” research data have shown that it has positive results in promoting of autonomy strategies that strengthen the treatment and prevention of victimization compared to the non-implementation of the same intervention (Lievense et al., 2019). This makes further research and continuous, systematic, and objective monitoring of the impact of inclusive education practices on improving social skills and combating victimization urgently needed. Among the educational practices that emerged are some that have previously been considered documented, promising or even of limited support. Future studies could help further investigate their effect on improving social skills and eliminating bullying victimization. It must also be said that the limited sample of the research affects the interpretation and generalization of the conclusions.

Conclusion

The findings of the study highlight specific, inclusive educational practices, which could be used in designing targeted interventions to develop social skills, social networking (Ung, 2016), good communication, and quality friendships that could protect and act as a deterrent for loneliness and victimization of ASD students (Locke et al., 2010).

Change history

29 February 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-024-00240-x

References

Aithal, S., Karkou, V., Makris, S., Karaminis, T., & Powell, J. (2021). A dance movement psychotherapy intervention for the wellbeing of children with an autism spectrum disorder: A pilot intervention study. Frontiers in Psychology, 2672. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.588418

American Psychiatric Association, D. S. M. T. F., & American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (Vol. 5, No. 5). Washington, DC: American psychiatric association.

Belidou, K. (2017). Autism spectrum disorder and victimization: teachers’ views of the association with theory of mind and friendship (Master thesis). University of Macedonia. http://dspace.lib.uom.gr/handle/2159/19925

Bitsika, V., Heyne, D. A., & Sharpley, C. F. (2021). Is bullying associated with emerging school refusal in autistic boys? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51, 1081–1092. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04610-

Blake, J. J., Lund, E. M., Zhou, Q., Kwok, O., & Benz, M. R. (2012). National prevalence rates of bully victimization among students with disabilities in the United States. School Psychology Quarterly, 27, 210–222. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000008

Bond, C., Hebron, J., & Oldfield, J. (2017). Professional learning among specialist staff in resourced mainstream schools for pupils with ASD and SLI. Educational Psychology in Practice, 33(4), 341–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2017.1324406

Cappadocia, M. C., Weiss, J. A., & Pepler, D. (2012). Bullying experiences among children and youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 266–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1241-x

Carothers, D. E., & Taylor, R. L. (2004). How teachers and parents can work together to teach daily living skills to children with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 19(2), 102–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/10883576040190020501

Cassady, J. M. (2011). Teachers’ attitudes toward the inclusion of students with autism and emotional behavioral disorder. Electronic Journal for Inclusive Education, 2(7), 5. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/ejie/vol2/iss7/5/

Chiu, Y. L., Kao, S., Tou, S. W., & Lin, F. G. (2018). Effects of heterogeneous risk factors on psychological distress in adolescents with autism and victimization experiences in Taiwan. Disability and Rehabilitation, 40(1), 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2016.1242173

Chou, W. J., Hsiao, R. C., Ni, H. C., Liang, S. H. Y., Lin, C. F., Chan, H. L., & Yen, C. F. (2019). Self-reported and parent-reported school bullying in adolescents with high functioning autism spectrum disorder: The roles of autistic social impairment, attention-deficit/hyperactivity and oppositional defiant disorder symptoms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(7), 1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071117

Chou, W. J., Wang, P. W., Hsiao, R. C., Hu, H. F., & Yen, C. F. (2020). Role of school bullying involvement in depression, anxiety, suicidality, and low self-esteem among adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00009

Christensen, L. L., Fryant, R. J., Neece, C. L., & Baker, B. (2012). Bullying adolescents with intellectual disability. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 5, 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315864.2011.637660

De Boer, A., Pijl, S. J., & Minnaert, A. (2011). Regular primary schoolteachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education: A review of the literature. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 15(3), 331–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110903030089

Gkatsa, T., & Antoniou I. (2024). Friendship and autism spectrum disorder (ASD): Correlation between friendships of high function (AHF) autism students and teachers’ educational practices in the context of inclusion in elementary education. (Unpublished, under review)

Goodman, G., & Williams, C. M. (2007). Interventions for increasing the academic engagement of students with autism spectrum disorders in inclusive classrooms. Teaching Exceptional Children, 39(6), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/004005990703900608

Gutstein, S. E. (2009). Empowering families through relationship developmental intervention: An important part of the biopsychosocial management of autism spectrum disorders. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2009-17490-005

Hassan, A., Pinkwart, N., & Shafi, M. (2021). Serious games to improve social and emotional intelligence in children with autism. Entertainment Computing, 38, 100417.

Hodgins, Z., Kelley, E., Kloosterman, P., Hall, L., Hudson, C. C., Furlano, R., & Craig, W. (2020). Brief report: Do you see what I see? The perception of bullying in male adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50, 1822–1826. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3739-y

Hsiao, M. N., Tai, Y. M., Wu, Y. Y., Tsai, W. C., Chiu, Y. N., & Gau, S. S. F. (2022). Psychopathologies mediate the link between autism spectrum disorder and bullying involvement: A follow-up study. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 121(9), 1739–1747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2021.12.030

Hu, H. F., Liu, T. L., Hsiao, R. C., Ni, H. C., Liang, S. H. Y., Lin, C. F., & Yen, C. F. (2019). Cyberbullying victimization and perpetration in adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: Correlations with depression, anxiety, and suicidality. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49, 4170–4180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04060-7

Humphrey, N., & Hebron, J. (2015). Bullying of children and adolescents with autism spectrum conditions: A ‘state of the field’ review. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 19(8), 845–862. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110903030089

Jin, X., Simmons, S. K., Guo, A., Shetty, A. S., Ko, M., Nguyen, L., & Arlotta, P. (2020). In vivo Perturb-Seq reveals neuronal and glial abnormalities associated with autism risk genes. Science, 370(6520), eaaz6063. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaz6063

Jordan, R. (2005). Managing autism and Asperger’s syndrome in current educational provision. Pediatric Rehabilitation, 8(2), 104–112.

Kerns, C. M., Maddox, B. B., Kendall, P. C., Rump, K., Berry, L., Schultz, R. T., & Miller, J. (2015). Brief measures of anxiety in non-treatment- seeking youth with autism spectrum disorder. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 19(8), 969–979. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361314558465

Kloosterman, P. H., Kelley, E. A., Craig, W. M., Parker, J. D., & Javier, C. (2013). Types and experiences of bullying in adolescents with an autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(7), 824–832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2013.02.013

Koegel, L. K., & Koegel, R. L. (2006). Pivotal response treatments for autism communication, social, & academic development. Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Kucharczyk, S., Shaw, E., Myles, B. S., Sullivan, L., Szidon, K., & Tuchman-Ginsberg, L. National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorder (NPDC). (2012). Guidance & Coaching on Evidence-Based Practices for Learners with Autism Spectrum Disorders. National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorders.

Lievense, P., Vacaru, V. S., Liber, J., Bonnet, M., & Sterkenburg, P. S. (2019). “Stop bullying now!” Investigating the effectiveness of a serious game for teachers in promoting autonomy-supporting strategies for disabled adults: A randomized controlled trial. Disability and Health Journal, 12(2), 310–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2018.11.013

Liu, T.-L., Hsiao, R. C., Chou, W.-J., & Yen, C.-F. (2021). Social anxiety in victimization and perpetration of cyberbullying and traditional bullying in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 5728. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115728

Locke, J., Ishijima, E. H., Kasari, C., & London, N. (2010). Loneliness, friendship quality and the social networks of adolescents with high-functioning autism in an inclusive school setting. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 10(2), 74–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2010.01148.x

Lord, C., Risi, S., Lambrecht, L., Cook, E. H., Leventhal, B. L., DiLavore, P. C., & Rutter, M. (2000). The autism diagnostic observation schedule—generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30, 205–223.

Maïano, C., Normand, C. L., Salvas, M. C., Moullec, G., & Aimé, A. (2016). Prevalence of school bullying among youth with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autism Research, 9(6), 601–615. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1568

Malinverni, L., Mora-Guiard, J., Padillo, V., Valero, L., Hervás, A., & Pares, N. (2017). An inclusive design approach for developing video games for children with autism spectrum disorder. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 535–549.

NasoudiGharehBolagh, R., Zahednezhad, H., & VosoughiIlkhchi, S. (2013). The effectiveness of treatment-education methods in children with autism disorders. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 84, 1679–1683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.07.013

Olweus, D. (1996). Revised Olweus bully/victim questionnaire. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment.

Pabian, S., & Vandebosch, H. (2016). An investigation of short-term longitudinal associations between social anxiety and victimization and perpetration of traditional bullying and cyberbullying. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, 328–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0259-3

Pater, M., Spreen, M., & van Yperen, T. (2021). The developmental progress in social behavior of children with autism spectrum disorder getting music therapy. A multiple case study. Children and Youth Services Review, 120, 105767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105767

Reiter, S., & Lapidot-Lefler, N. (2007). Bullying among special education students with intellectual disabilities: Differences in social adjustment and social skills. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 45(3), 174–181. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556(2007)45[174:BASESW]2.0.CO;2

Rowley, E., Chandler, S., Baird, G., Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Loucas, T., & Charman, T. (2012a). The experience of friendship, victimization and bullying in children with an autism spectrum disorder: Associations with child characteristics and school placement. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(3), 1126–1134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2012.03.004

Rowley, E., Chandler, S., Baird, G., Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Loucas, T., & Charman, T. (2012b). The experience of friendship, victimization and bullying in children with an autism spectrum disorder: Associations with child characteristics and school placement. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(3), 1126–1134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2012.03.004

Russell, A., Scriney, A., & Smyth, S. (2022). Educator attitudes towards the inclusion of students with autism spectrum disorders in mainstream education: A systematic review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-022-00303-z

Sam, A. M., Odom, S. L., Tomaszewski, B., Perkins, Y., & Cox, A. W. (2021). Employing evidence-based practices for children with autism in elementary schools. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51, 2308–2323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04706-x

Schmid, L., DeMoss, L., Scarbrough, P., Ripple, C., White, Y., & Dawson, G. (2020). An investigation of a classroom-based specialized music therapy model for children with autism spectrum disorder: Voices together using the VOICSS™ method. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 35(3), 176–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357620902505

Segall, M. J., & Campbell, J. M. (2007). Autism inclusion questionnaire. Unpublished measure.

Segall, M. J., & Campbell, J. M. (2012). Factors relating to education professionals’ classroom practices for the inclusion of students with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(3), 1156–1167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2012.02.007

Segall, M. J., & Campbell, J. M. (2014). Factors influencing the educational placement of students with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(1), 31–43.

Simpson, R., de Boer-Ott, S., Griswold, D., Myles, B., Byrd, S., Ganz, J., et al. (2005). Autism spectrum disorders: Interventions and treatments for children and youth. Corwin Press.

Skipitari, B. (2016). Inclusion of students with autism: Experience, knowledge, attitudes and strategies of primary education teachers (Master thesis). University of Western Macedonia - Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. http://dspace.uowm.gr:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/436

Sofronoff, K., Dark, E., & Stone, V. (2011). Social vulnerability and bullying in children with Asperger syndrome. Autism, 15(3), 355–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361310365070

Solberg, M. E., & Olweus, D. (2003). Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Aggressive Behavior: Official Journal of the International Society for Research on Aggression, 29(3), 239–268. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.10047

Sreckovic, M. A., Brunsting, N. C., & Able, H. (2014). Victimization of students with autism spectrum disorder: A review of prevalence and risk factors. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(9), 1155–1172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.06.004

Steele, M., Hodges, J., Kaniuk, J., Hillman, S., & Henderson, K. A. Y. (2003). Attachment representations and adoption: Associations between maternal states of mind and emotion narratives in previously maltreated children. Journal of Child Psychotherapy, 29(2), 187–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/0075417031000138442

Sterzing, P. R., Shattuck, P. T., Narendorf, S. C., Wagner, M., & Cooper, B. P. (2012). Bullying involvement and autism spectrum disorders. Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, 156(11), 1058–1064. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.790

Ung, D. (2016). Peer victimization in youth with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder (Doctoral dissertation, University of South Florida). https://www.proquest.com/openview/3bcee3b71c5d5e3df4d5b07292a04626/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750

Van Schalkwyk, G., Smith, I. C., Silverman, W. K., & Volkmar, F. R. (2018). Brief report: Bullying and anxiety in high-functioning adolescents with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48, 1819–1824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3378-8

Wainscot, J. J., Naylor, P., Sutcliffe, D. T., & Williams, J. V. (2008). Relationship with peers and use of the school environment of mainstream secondary school pupils with Asperger syndrome (high-functioning autism): A case–control study. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/560/56080103.pdf

Weiss, J. A., Cappadocia, M. C., Tint, A., & Pepler, D. (2015). Bullying victimization, parenting stress, and anxiety among adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research, 8, 727–737. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1488

Yeung, A. W. K., Tosevska, A., Klager, E., Eibensteiner, F., Laxar, D., Stoyanov, J., & Willschke, H. (2021). Virtual and augmented reality applications in medicine: analysis of the scientific literature. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(2), e25499.

Zablotsky, B., Bradshaw, C. P., Anderson, C. M., & Law, P. (2014). Risk factors for bullying among children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 18(4), 419–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361313477920

Zeedyk, S. M., Rodriguez, G., Tipton, L. A., Baker, B. L., & Blacher, J. (2014). Bullying of youth with autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, or typical development: Victim and parent perspectives. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(9), 1173–1183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.06.001

Funding

Open access funding provided by HEAL-Link Greece. There was no funding of any kind in the present study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The co-author’s contribution to the research process was very important. He contributed to the writing of the research process in this article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Throughout the process, the principles of respect and protection of human rights were followed (Declaration of Helsinki). There was a commitment to use the data exclusively for research purposes, and participation was voluntary and completely anonymous. Absolute anonymity and protection of the personal data of the teachers who answered the questionnaire were maintained, as well as any information about the children that they were referring to. The proof of this was that the questionnaire was circulated through “Educational, Counselling and Support Centers” (ECSc), which mediated the transmission of the questionnaire from “Educational, Counselling and Support Centers” (ECSc) to primary schools that had high-functioning autistic students. Absolutely no information was given about the teachers and the students. That is why we do not know the total number of students to which the responses of the teachers who made up our sample refer. The absolute protection of personal data is described in detail in the following excerpt from the article: “The process of collecting the empirical material took place during the school year 2022–2023. In particular, in February 2023, there was a telephone contact with the Educational and Counseling Support Centers (ECSc) of Ioannina, Patras, Kozani and Aitoloakarnania, in order to approve the request for the distribution of the electronic questionnaires to primary education schools where AHF children attend. Due to the protection of the personal data of students with AHF, no information about the personal data of students with AHF (gender, age, school and class attended) was provided to the research team. Given these constraints, it was decided that the questionnaires would be administered through the ECSc without direct contact between the research team and the principals or teachers of schools attended by students with AHF. The request was accepted, in March, and then the questionnaire was distributed electronically by the ECSc through an online Google platform to the principals of public primary schools, general education, of four regional units in Greece, namely the prefectures of Achaia, Ioannina and Aitoloakarnania and Kozani. The principals undertook to forward it to the teachers who teach children with ASD in the respective school units. The questionnaires were accompanied by an information letter, informing about the purpose of the survey, voluntary and anonymous participation, clarification of the basic terms and contact details of the research team.”

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

The original version of this article titled “Bullying and Autism Spectrum Disorder: Correlating the Victimization of High-Functioning Autism Students with Educational Practices in the Context of Inclusion in Primary Education” published online on the 20th of January 2024 has an incorrect presentation of the Authors names - first and last names were interchanged. The first author’s surname should be "Gkatsa" and the first name should be "Tatiani". While second author's surname should be "Antoniou" and the first name is "Irene".

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gkatsa, T., Antoniou, I. Bullying and Autism Spectrum Disorder: Correlating the Victimization of High-Functioning Autism Students with Educational Practices in the Context of Inclusion in Primary Education. Int Journal of Bullying Prevention (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-023-00208-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-023-00208-3