Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a chronic progressive neurological disease clinically characterized by motor and non-motor symptoms, with an increasing impact on the quality of life not only for the patient but also for the caregivers. Twenty-six primary caregivers (female = 19; mean age = 57.04, SD = 10.64) of PD patients were consecutively recruited. Several psychological aspects were verified through clinical screening tests: EQ-5D and PQoL CARER for quality of life, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI), Family Strain Questionnaire (FSQ), and Adult Attachment Questionnaire. We found that the burden was generally higher in cohabiting female caregivers of patients with dementia as compared with not cohabiting caregivers. Severe burden emerged in 7.7% of the participants according to the PQoL. The mean score of this scale was higher in cohabiting caregivers. Finally, according to the CBI, 19.2% of the participants suffered from severe burden, with mean scores of the CIB-S and CIB-E subscales higher in cohabitants. Our study highlights the need to investigate more thoroughly the burden of caregivers of PD patients and its associated factors, and to pay more attention to the physical and psychological health of caregivers to improve their quality of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a slowly progressive neurodegenerative disorder that mainly involves certain functions such as movement control and balance. It belongs to a group of pathologies termed “movement disorders” and is the most frequent of these (WHO, 2023).

Already in 1998, Martínez-Martín introduced the concept of Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) in patients with PD as an important factor to consider in the management of chronic, progressive, and complex diseases (Martínez-Martín, 1998).

In particular, in patients with PD undergoing drug therapy and with controlled motor symptoms, HRQoL is mainly influenced by cognitive decline and autonomic and psychiatric symptoms (Schrag et al., 2000). According to some studies, depression (Hinnell et al., 2012) and cognitive decline with reduced attention and concentration problems (Lawson et al., 2016) are the aspects that mostly affect HRQoL. The effect of the medication is therefore assessed not only by its efficacy on motor and non-motor symptoms but also by its impact on the patient’s HRQoL.

Moreover, PD is associated with a marked deterioration in HRQoL of the patient and the caregivers, representing a real emotional, economic, and social problem. Indeed, caring for a patient with PD can sometimes take on negative connotations that compromise continuity or cause a deterioration in the relationship between patient and caregiver, often also due to a change in roles or personality (Jensen et al., 2017; Sögüt & Dündar, 2017).

According to Hiseman and Facjrell (2017), a caregiver’s burden can be defined as the strain or load placed on a person caring for a chronically ill, disabled, or elderly family member. It is a multidimensional response to the physical, psychological, emotional, social, and economic stressors associated with the caregiver experience.

As the disease progresses, the patient requires more and more support due to the loss of autonomy as a consequence of the onset of non-motor symptoms. All these factors represent stressors for the caregiver and negatively impact their daily life and health (Hiseman & Fackrell, 2017).

Female sex, low educational attainments, financial stress, caregiving time, and efforts, as well as the lack of choice, depressive symptoms, and perceived patient distress, have been identified among the risk factors that affect the caregiver’s burden (Adelman et al., 2014).

Another factor influencing caregiver burden is the attachment style of the caregiver. The attachment theory was aimed to address the development of human personality and the ethological systems, which extend from the relationship between parents and offspring to the affectional bonds throughout the life course (Ainsworth & Bowlby, 1991). In the light of a mutual influence between individuals and the environment, the adult attachment systems were found as frequently tied to one’s physical health by regulating or mediating emotions, relationships, and behavior (Pietromonaco & Beck, 2019). On the other hand, early life experiences and proximal interpersonal security or insecurity in adult relational contexts can rely on distal or ongoing attachment experiences (Fraley & Roisman, 2019).

Following the four-category adult attachment model by Bartholomew and Horowitz (1991), the secure, preoccupied, dismissing, and fearful attachment styles were tested across different cultures (Chui & Leung, 2016; You & Malley-Morrison, 2000), while reflected the role of attachment systems on one’s interpersonal functioning and parental bonding in adulthood (Hoenicka et al., 2022).

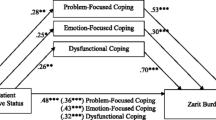

A recent longitudinal study on care-seeking styles by Romano et al. (2022) explored the role of caregiving self-efficacy on older parents (i.e., care recipients) without moderate to severe cognitive impairment. Hence, the self-efficacy of adult children as caregivers, with higher anxious or avoidant attachment styles, reflected a constructive and indirect form of care-seeking, which may refer to a cooperative care recipient; it is focused on positive problem-solving, and it includes a help-seeking behavior that is passive or unclear to the caregiver (Gomes et al., 2018; Tateo at al., 2018; Collins & Feeney, 2000; Romano et al., 2022; Sillars et al., 2002). The data from the scientific field suggest that a secure caregiver can be seen as being able not only to make use of existing social supports but also, above all, cope with and integrate the emotions concerning his or her relative, being more emotionally available and decreasing the subjective feeling of the burden that the illness entails (Pezzati et al., 2005). Conversely, insecure attachment styles in a caregiver may spill over into situations of increased conflict, ambivalent feelings, and difficulty in coping and regulating emotions. In fact, the role of adult attachment styles indicated that the attachment anxiety of caregivers was negatively tied to a greater degree of resolution of PD (Goldberg, 2022).

In cross-sectional studies on caregivers of patients with dementia, the insecure adult attachment styles of the caregiver were tied to a greater burden, anxiety, and dysfunctional coping strategies (Cooper et al., 2008), whereby their own secure attachment styles were also associated with lower levels of psychiatric symptoms (Crispi et al., 1997).

Hypothesis

Caregivers of patients with dementia have a worse health status, greater difficulty in carrying out usual activities, greater pain and discomfort, and anxiety/depression.

PD can impair caregiver well-being because the patient’s mood and disability, the severity of the disease, the patient’s and caregiver’s quality of life, and the caregiver’s psychological well-being are identified as the most important indicators of burden.

The anxious attachment style affects the well-being of caregivers of people with dementia disorders and there is a complex bond in their relationship quality.

Aims

In the present study, we aimed to analyze the health status, psychological aspects, and quality of life of caregivers of PD patients with reference also to the attachment style assessed in adulthood.

Materials and Methods

Procedure

The study was conducted at the “Movement Disorders Outpatient Clinic” of the Department of Neurology of the “San Giovanni di Dio e Ruggi d’Aragona” University Hospital (Salerno, Southern Italy), which follows approximately 2000 patients and their caregivers.

In the present study, the sample was recruited consecutively and the following inclusion criteria were adopted (Postuma et al., 2015):

-

a)

absence of absolute exclusion criteria for a diagnosis of PD,

-

b)

presence of at least 2 of the 4 cardinal signs (one of which must be tremor or bradykinesia),

-

c)

absence of secondary or atypical parkinsonism symptoms.

The subjects went to the Hospital as caregivers of the patient with PD and were recruited at the end of the routine check-up.

At the outset, the purpose of the study was briefly explained to the caregiver, and they were asked to provide informed consent for participation in the experimental protocol and data collection.

Data collection was based on a questionnaire consisting of standardized screening scales for the assessment of the anxiety-depressive axis, quality of life, and attachment styles. At the end of the compilation, anamnestic and clinical data concerning the patient and his/her illness and the caregiver’s personal data were noted.

The data collected concerning the patient and his or her disease were age, sex, duration of disease (in years), stage of disease (assessed by Hoehn and Yahr index), motor severity (assessed by UPDRS III scale), and the possible presence of dementia associated with PD.

The data collected regarding the caregiver were age, sex, schooling (in years), degree of relationship to the patient, occupation, whether cohabiting with the patient/family member, and the number of hours per day caring for the patient/family member.

Tools

The screening tests used are the following:

-

EQ-5D (The EuroQol Group, 1990, 2009), which was used to assess the perception of one’s own health status ascribable to 5 dimensions (mobility, personal care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression). The EQ-5D questionnaire also includes a visual analog scale (VAS) with which the caregiver expresses his/her perceived overall health level through a value ranging from 0 (worst imaginable health status) to 100 (best imaginable health status). From the five dimensions of the EQ-5D, a synthetic index with a maximum score of 1 indicating the best health status is derived by conversion, while the higher the scores of the individual questions, the more severe or frequent the problems are.

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, HADS (Zigmond & Snaith, 1983; Italian validation by Costantini et al., 1999), was used to assess levels of anxiety and depression; it comprises 14 questions with 4 possible answers corresponding to a score of 0 to 3. This results in two subscales, one for anxiety (HADS-A) and one for depression (HADS-D), which constitute two independent measures. In both cases, the cutoff > = 8 (in relation to generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive episodes, respectively). The HADS is divided into four grades: normal (0–7), mild (8–10), moderate (11–15), and severe (16–21).

-

PQoL Carer (Italian validation by Picillo et al., 2019), consisting of 26 items, was used to assess the HR-QoL perceived by caregivers of patients with PD. A cut-off > 62 was proposed to identify caregivers with a severe burden and a severe level of anxiety/depression. Overall life satisfaction (LF) was assessed on a scale from 0 (extremely dissatisfied) to 100 (extremely satisfied).

-

Caregiver Burden Inventory, CBI (Novak & Guest, 1989; Italian validation Greco et al., 2017), is a caregiver burden assessment instrument consisting of 24 questions and divided into 5 sections that allow for the assessment of different stress factors: objective burden (T), psychological burden (S), physical burden (F), social burden (D), and emotional burden (E). In the adult population, a score of > 36 is conventionally used to indicate the need for respite care.

-

Family Strain Questionnaire Short Form, FSQ-SF (Vidotto et al., 2010), was used to identify the level of stress and strain experienced by the caregiver in caring for a relative. It is made up of 30 dichotomous (“yes” or “no”) questions placed in order of severity and grouped into areas of increasing psychological risk:

-

OK area: the caregiver is reacting well to the situation.

-

Area R (recommended): the caregiver is reacting sufficiently well but with some inability to adapt. Psychological consultation is recommended if the symptoms worsen.

-

Area SR (strongly recommended): the caregiver presents an evident strain that requires psychological assessment and support.

-

Area U (urgent): the caregiver presents significant strain and high psychological risk. It is urgent that he/she be seen by a psychologist or psychiatrist.

-

-

The Adult Attachment Questionnaire (AAQ) consists of 56 items and detects on 4 scales the prototypes derived from the attachment styles proposed by Bartholomew and Horowitz (1991); Italian validation by Troisi et al. (2022): “secure,” “preoccupied,” “dismissing,” and “fearful.”

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses were carried out for the mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) of the variables under study. A comparison of the averages of the scores obtained on the screening scales between the subgroups of the sample caregivers according to specific variables (“sex,” “cohabitation,” “presence/absence of dementia”) was carried out by means of Student’s t-test. IBM SPSS v.23 statistical software was used.

Results

Participants

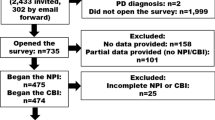

Twenty-six caregivers were consecutively recruited (CG; female = 19; mean age = 57.04, SD = 10.64). The CG sample had an education level (expressed in years) of 13.24 (SD = 4.46); 50% were employed in manual work, 38.5% were employed in intellectual work, and 11.5% were retired. The CG group spent an average of 12.85 (SD = 10.78) hours per day caring for their family member with PD. A total of 76.9% of them lived with their assisted parent; 61.5% were patients’ spouses; and 38.5% were patients son/daughter.

With regard to the group of patients (P; male = 19; mean age = 72.27 years, SD = 10.54 years), the mean disease duration (expressed in years) was 7.62 (SD = 4.75). Mean Hoehn and Yahr stage was 2.69 ± 0.54) and mean UPDRS III score was 28.46 ± 11.35). Moreover, 19.2% of the patients were demented.

All characteristics of the two groups are shown below (see Table 1).

Caregivers Quality of Life

In order to assess the caregivers’ quality of life, the EQ-5D and PQoL test scores were analyzed (see Supplementary 1_Table 2).

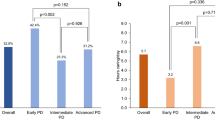

When comparing the mean scores obtained on the EQ-5D, we observed that female caregivers had a higher mean score (7.05 ± 1.64) than male caregivers (6.71 ± 2.87); on the other hand, they had a lower mean score on the EQ-VAS scale (73.42 ± 16.75 vs. 80.71 ± 9.32). Moreover, the EQ-VAS value was lower in the caregivers of patients with dementia (71 ± 18.84), indicating that the caregivers’ quality of life is affected by the presence of the patient’s dementia; lower mean values were also present in the subscales related to habits (1.40 ± 0.54), anxiety-depression (1.80 ± 0.83), and pain-annoyance (2 ± 0.70). Finally, caregivers cohabiting with patients showed lower mean scores in terms of EQ-VAS. This result is statistically significant (p = < 0.05). Furthermore, the mean total score (EQ-5D-TOT) was higher in cohabiting caregivers (p > 0.05). The “anxiety/depression” subscale showed higher mean scores in the cohabiting caregivers, and the difference in mean scores compared with the non-cohabiting caregivers was greater than in the remaining parameters (p > 0.05). This means that not only do the cohabiting caregivers suffer more from anxiety and depression than the non-cohabiting caregivers but also this problem characterizes them more than the other dimensions assessed by the EQ-5D subscales.

A severe level of burden was found in 7.7% of the caregivers participating in the study.

The caregiver group was assessed according to the variables “sex” and “cohabitation.” Females had a higher total life satisfaction (LF) score than males but were more satisfied than males with their life, in general (p > 0.05). Cohabitants showed a higher total score (p < 0.05) and a lower LF score than non-cohabitants (p > 0.05).

Anxiety-Depression Axis

With regard to anxiety-depressive symptoms, the interpretation of the HADS-A and HADS-D scale scores (see Supplementary 1_Table 3) showed that while the level of depression was similar in both sexes, males suffered more from anxiety disorders than females (23.29 ± 1.79 vs. 22.21 ± 1.58).

Comparing the two scales according to the variable “cohabitation,” the mean HADS-A score was only slightly higher in non-cohabitants. The mean HADS-D score was higher in cohabitants. Both cohabitants and non-cohabitants had higher mean scores (p > 0.05) in terms of HADS-A than in HADS-D.

Caregivers who cohabited with their relative/caregiver had lower levels of anxiety but higher mean scores in the depressive dimension (see Supplementary 1_Table 3).

Caregivers’ Burden and Stress

CBI demonstrated the presence of burden (score > 36) in 19.2% of the interviewed caregivers.

The mean scores of the CBI subscales were analyzed according to the variables “sex” and “cohabitation” (see Supplementary 1_Table 4). Male caregivers showed higher mean scores (7.14 ± 5.04) than female caregivers (5.32 ± 6.18) in the CBI-T subscale (p > 0.05), while female caregivers showed higher mean scores (2.53 ± 3.09) in the CIB-D (p > 0.05).

Non-cohabitant caregivers presented higher mean scores (8.33 ± 6.37) than cohabitant caregivers (5.05 ± 5.64) in the CBI-T subscale (p > 0.05), while cohabitant had higher mean scores (3.55 ± 3.31) than non-cohabitant caregivers (0.50 ± 0.83) in the CBI-S subscale (p < 0.05) The mean CBI-E score was higher in cohabitants than non-cohabitants (p < 0.05).

Concerning the areas of intervention identified by the FSQ questionnaire, it emerges that 88.5% of the caregivers fall in AREA U and 11.5% in AREA SR. The mean scores of the FSQ questionnaire for the four areas were analyzed according to the variables “sex” and “cohabitation.” Male caregivers had a higher mean score in all FSQ areas (p > 0.05). The mean score of FSQ-AREAOK and FSQ-AREAR did not seem to vary significantly according to cohabitation. The mean score of FSQ-AREASR and FSQ-AREAU was higher in the case of non-cohabiting caregivers (p > 0.05) (see Supplementary 1_Table 4).

Caregiving and Attachment Styles

According to the degree of relationship, the mean score of the prototype “secure” (S) was only slightly higher in the spouses than in the sons/daughters, and the same result was seen for the prototype “preoccupied” (P). The avoidant prototype (A) showed a higher mean score in the spouses, similar to the fearful prototype (F). As the difference in mean scores between spouses and sons/daughters was greater for prototypes A and F than for the others, these attachment modes particularly involved the spouses. However, this result was not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (see Supplementary_Table 5).

In relation to the variable presence/absence of dementia in the family member being cared for, higher mean scores emerged in the four attachment styles investigated in caregivers of patients with dementia than in those with patients without dementia. Above all, the higher presence of prototype F was found in caregivers with family members with dementia compared to others (22.67 ± 7.57 vs 1.62 ± 1.74; p > 0.05) (see Supplementary_Table 5).

Discussion

As described in the section “Hypothesis” the present work focused on the association between caregiver burden and the anxiety-depression axis, as well as investigating the health status, psychological aspects, and quality of life of caregivers of patients with PD. In addition, a useful insight was made into the significance of attachment styles in adulthood in modulating caregivers’ burden.

The results of the EQ-5D questionnaire showed that males had a better health status on average than females, and, in particular, females suffered more from anxiety and depression. An important finding from our study concerns cohabitation: cohabiting caregivers show significantly worse health status than non-cohabiting caregivers and present more anxiety/depression. Finally, the importance of factors such as caregiver age, caregiving hours, and cohabitation on overall health status (EQ-VAS) was showed. This result is consistent with a previous study reporting the importance of caregiver age and caregiving hours in determining caregiver burden (Macchi et al., 2020). The HADS questionnaire showed that both males and females were at greater risk of suffering from anxiety disorders than from depression. The same applies to cohabitants and non-cohabitants. Males tended to be more anxious than females. Non-cohabitants tended to be more anxious than cohabitants, probably due to the fact that they cannot constantly control the patient. Finally, cohabitants suffered more from depression than non-cohabitants.

Caregivers’ attachment patterns were analyzed using the AAQ questionnaire, which distinguishes subjects into four prototypes: “secure,” “preoccupied,” “avoidant,” and “fearful.” The questionnaire made it possible to bring out the different attachment styles between spouses and sons/daughters. In fact, according to the degree of kinship, “avoidant” and “fearful” attachment styles were found more in spouses than in sons/daughters.

A severe level of burden was found with the PQoL Carers questionnaire in 7.7% of the carers who participated in the study. Although female subjects scored higher on average than males, they reported greater life satisfaction, in general. From the analysis of the scientific literature, numerous studies have revealed gender differences in caregiving (Carpinelli & Watzlawik, 2023; Carpinelli et al., 2022; Marinaci et al., 2021). Specifically, activations of caregiving bonds have emerged in female caregivers compared to male caregivers. This correlates with the fact that although female caregivers have a higher perceived burden, they are more satisfied on the LF scale. The collected data showed that cohabiting caregivers have a worse quality of life than non-cohabiting caregivers and lower life satisfaction, in general.

The presence of burden was found with CBI in 19.2% of the interviewed caregivers. This is actually a relevant finding since CBI encompasses five types of stress factors and a high score indicates an important impact on the caregiver’s life, which may be affected in several aspects.

In males, the objective load, describing the burden associated with the restriction of caregiver time (CIB-T), is higher, whereas in females, the social load, describing the perception of role conflict (CIB-D), is higher. In non-cohabitants, the objective load is greater (CIB-T).

We hypothesize that not living with the patient causes greater perceived time restriction for the caregiver, who may have to give up other outside activities in order to travel to the patient’s home, while in cohabitants the psychological load is greater, describing the caregiver’s perception of feeling cut off from the expectations and opportunities of their peers (CIB-S).

The mean CIB-E score was higher in cohabitants and represented the emotional burden of describing the feelings toward the patient. Males had a higher mean score in all FSQ areas. This reflects the gender differences in adaptation and coping strategies also mentioned above.

The mean score of FSQ-AREAOK and FSQ-AREAR did not seem to vary significantly depending on cohabitation. The mean scores of FSQ-AREASR and FSQ-AREAU were higher in the case of non-cohabiting caregivers. This test assesses strain within the family group. It is possible that due to being away from their family members, caregivers perceive more distress and frustration in the adaptation of care as there is no constant daily monitoring of patients needs and requirements.

Caregiver burden (CB) refers to the health outcomes that the relatives and the carers of patients who are affected by severe illness face on their own journey in providing informal care throughout the onset and the progression of a particular disease in others (Liu et al., 2020; Maguire & Maguire, 2020; Ransmayr, 2021).

In accordance with the literature data, it emerges from this study that the majority of caregivers of patients with PD are female and elderly (Ransmayr, 2020).

Confirming the reports in the literature, the study showed that caregivers of patients with dementia (Martinez-Martin et al., 2015) had a worse health status, complaining of greater difficulty in carrying out usual activities, suffering more pain and discomfort and anxiety/depression.

A previous study reported that caregivers of PD patients suffered more from mood disorders and had a worse quality of life than the general population. The affective state was found to be the most influential factor on the caregiver’s burden and perceived health (Martinez-Martin et al., 2008). Moreover, the patient’s mood and disability and the severity of the disease as well as the patient’s and caregiver’s quality of life and the caregiver’s psychological well-being were identified as the most important indicators of burden, showing that PD can impair caregiver well-being (Martinez-Martin et al., 2007).

The anxious attachment style was found to affect the well-being of caregivers for people with seizure disorders and suggested a complex bond on their relationship quality (Wardrope et al., 2019).

Contrasting attachment orientations of care recipient and caregiver (e.g., anxious versus avoidant), the presence of dyadic relationships involving adult children caring for their older parents, along with the presence of more insecure attachment styles, has been found to predict the caregivers’ burden in the context of family caregiving (Romano et al., 2020).

In a longitudinal study of PD patients undergoing device-aided therapies (DAT), higher avoidant attachment styles were found in the caregivers, while the care recipients showed higher anxious attachment styles (Scharfenort et al., 2021).

Given a more in-depth association with the CB, those care recipients who own either premorbid avoidant or anxious-ambivalent attachment styles were more likely to have paranoid delusions or anxiety in dementia, resulting in a greater degree of caregiving burden (Magai & Cohen, 1998). Moreover, higher avoidant attachment levels of the caregiver were tied to increased behavioral problems in the care recipient with dementia, and those were longitudinally linked to the overall well-being of caregivers (Perren et al., 2007).

Whether the filial obligation, namely, one’s own sense of duty regarding the caregiving responsibilities toward a significant adult, was shown to increase the CB in those with greater avoidance attachment styles (Lee et al., 2018), the presence of parent fixation in care recipients, their attachment behavior, and the symptoms associated with the progression of dementia were linked to the adult attachment systems and its potential contribution to both the patient/care recipient and the caregiver’s psychological health (Nelis et al., 2014).

The impact on social life due to caregiving has also been highlighted in the literature (Schrag et al., 2006): our data suggest the urgency of a global “taking charge” that, in the face of the generalized suffering and impasses that accompany the conditions in which PD begins and develops, consider caring for the individual within the contexts of everyday life, acting on the enhancement of resources and aiming to raise the quality of life of all those involved.

Alongside forms of material, economic, and welfare support, it is of fundamental importance to accompany each person to find the position most suited to his or her resources and abilities, while at the same time promoting mutuality and the expansion of social ties in the community.

Conclusions

The present study, albeit with the limitations resulting from the small sample size, highlights the need to investigate more thoroughly the burden of caregivers of patients with PD and the factors associated with it.

Caregivers often feel powerless in the face of PD. It is important to recognize and manage these feelings. Interventions that carers can benefit from to reduce the burden and discomfort associated with caring and find support in their role can be grouped into the following categories: support groups, cognitive behavioral therapy, psycho-educational therapy, and mindfulness-based stress reduction.

Support groups play a valuable role for carers by facilitating shared experiences, close connections, and the dissemination of education on disease processes. For example, the Caregivers’ Attachment and Relationship Education (CARE) course (Poyner-Del Vento et al., 2018) was developed to help caregivers to understand the changing nature of their attachment bond with a veteran family member, process any related unmet attachment needs or losses resulting from PD, and adapt to these changes by building communication skills, practicing self-care, and expanding their social networks.

The Parkinson’s Patient Education Program (PEPP) is a standardized psychosocial intervention program aimed at improving the HRQoL of PD patients and caregivers Thanks to this intervention, it was shown that caregivers’ mood improved, as did their psychosocial functioning: about 90% agreed that the exchange of experiences within the group was helpful; more than half reported an improvement in their understanding of PD; more than 50% said they could cope better with problems due to the disease; and 50% of patients and caregivers had improvements in stress management (A’Campo et al., 2010).

Similar results were confirmed by another study whose data indicate that awareness and psychological flexibility are positive contributors to resilience against caregiver burden. Mindfulness is defined as the tendency to intentionally bring one’s attention to experiences occurring in the present moment without judgment. Psychological flexibility refers to the extent to which a person can cope with changing circumstances and think about problems and tasks in new and creative ways (Klietz et al., 2021).

Future interventions to reduce the burden of PD caregivers could therefore be improved with the inclusion of mindfulness training programs.

As a consequence, more attention should be paid to the physical and psychological health of caregivers, implementing specific pathways and interventions with the aim of improving their quality of life.

Limitations and Future Lines of the Research

This contribution preliminarily analyzes, with a quantitative approach, the construct of caregiver burden in association with multiple factors and dimensions that may influence QoL. However, the present study is part of a much broader research protocol characterized by a mixed approach (qualitative-quantitative data) in which open-ended semi-structured interviews were planned. In fact, the next line of research is to implement a qualitative approach analysis of microgenesis and the emergence of meaning-making, referring to ecological phenomena and investigating how PD caregivers structure space and time in relation to their family members and themselves. In accordance with Aktualgenese, whose imperative is to analyze meaning-making and its antecedents (Boesch, 2021), stress is an ecological phenomenon that cannot simply be measured with a questionnaire and quantitative studies.

Availability of Data and Materials

All of the material is owned by the authors and/or no permissions are required.

References

A’Campo, L. E., Wekking, E. M., Spliethoff-Kamminga, N. G., Le Cessie, S., & Roos, R. A. (2010). The benefits of a standardized patient education program for patients with Parkinson’s disease and their caregivers. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 16(2), 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2009.07.009

Adelman, R. D., Tmanova, L. L., Delgado, D., Dion, S., & Lachs, M. S. (2014). Caregiver burden: A clinical review. JAMA, 311(10), 1052–1060. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.304

Ainsworth, M. S., & Bowlby, J. (1991). An ethological approach to personality development. American Psychologist, 46(4), 333–341. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.46.4.333

Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(2), 226–244. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.2.226

Boesch, E. E. (2021). Musik. Psychosozial-Verlag.

Carpinelli, L., Marinaci, T., & Savarese, G. (2022). Caring for daughters with anorexia nervosa: A qualitative study on parents’ representation of the problem and management of the disorder. Healthcare (basel), 10(7), 1353. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071353

Carpinelli, L., & Watzlawik, M. (2023). Anorexia nervosa in adolescence: Parental narratives explore causes and responsibilities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20, 4075. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054075

Chui, W.-Y., & Leung, M.-T. (2016). Adult attachment internal working model of self and other in Chinese culture: Measured by the Attachment Style Questionnaire — Short Form (ASQ-SF) by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and item response theory (IRT). Personality and Individual Differences, 96, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.02.068

Collins, N. L., & Feeney, B. C. (2000). A safe haven: An attachment theory perspective on support seeking and caregiving in intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(6), 1053–1073. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.6.1053

Cooper, C., Owens, C., Katona, C., & Livingston, G. (2008). Attachment style and anxiety in carers of people with Alzheimer’s disease: Results from the LASER-AD study. International Psychogeriatrics, 20(03). https://doi.org/10.1017/S104161020700645X

Costantini, M., Musso, M., Viterbori, P., et al. (1999). Detecting psychological distress in cancer patients: Validity of the Italian version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Supportive Care in Cancer, 7, 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s005200050241

Crispi, E. L., Schiaffino, K., & Berman, W. H. (1997). The contribution of attachment to burden in adult children of institutionalized parents with dementia. The Gerontologist, 37(1), 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/37.1.52

EuroQol Group. (2009). Questionario sulla Salute Versione italiana per l’Italia (Italian version for Italy). Retrieved September 17, 2021, from http://centrostudi.anmco.it/csweb/uploads/12-Questionario_EQ-5D-5L.pdf

Fraley, R. C., & Roisman, G. I. (2019). The development of adult attachment styles: Four lessons. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 26–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.008

Greco, A., Pancani, L., Sala, M., Annoni, A. M., Steca, P., Paturzo, M., & Vellone, E. (2017). Psychometric characteristics of the caregiver burden inventory in caregivers of adults with heart failure. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 16(6), 502–510.

Gomes, R., Dazzani, V., & Marsico, G. (2018). The role of responsiveness within the self in transitions to university. Culture & Psychology, 24(1), 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X17713928

Goldberg, A. (2022). Resolution of a parent’s disease: Attachment and well-being in offspring of parents diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease, 12(3), 1003–1012. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-212931

Hinnell, C., et al. (2012). Nonmotor versus motor symptoms: How much do they matter to health status in Parkinson’s disease? Journal of Movement Disorders, 27, 236–241.

Hiseman, J. P., & Fackrell, R. (2017). Caregiver burden and the nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. International Review of Neurobiology, 133, 479–497.

Hoenicka, M. A. K., López-de-la-Nieta, O., Martínez Rubio, J. L., Shinohara, K., Neoh, M. J. Y., Dimitriou, D., Esposito, G., & Iandolo, G. (2022). Parental bonding in retrospect and adult attachment style: A comparative study between Spanish, Italian and Japanese cultures. PLOS ONE, 17(12), e0278185. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278185

Jensen, M. P., Liljenquist, K. S., Bocell, F., et al. (2017). Life impact of caregiving for severe childhood epilepsy: Results of expert panels and caregiver focus groups. Epilepsy & Behavior, 74, 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2017.06.012

Klietz, M., Eichel, H. V., Staege, S., Kutschenko, A., Respondek, G., Huber, M. K., Greten, S., Höglinger, G. U., & Wegner, F. (2021). Validation of the Parkinson’s disease caregiver burden questionnaire in progressive supranuclear palsy. Parkinsons Disease, 10(2021), 9990679. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9990679.PMID:34046156;PMCID:PMC8128535

Lawson, R. A., et al. (2016). Cognitive decline and quality of life in incident Parkinson’s disease: The role of attention. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 27, 47–53.

Lee, J., Sohn, B. K., Lee, H., Seong, S. J., Park, S., & Lee, J.-Y. (2018). Attachment style and filial obligation in the burden of caregivers of dementia patients. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 75, 104–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2017.12.002

Liu, Z., Heffernan, C., & Tan, J. (2020). Caregiver burden: A concept analysis. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 7(4), 438–445.

Macchi, Z. A. et al. (2020). Patient and caregiver characteristics associated with caregiver burden in Parkinson’s disease: A palliative care approach. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 9, S24-S2S33.

Magai, C., & Cohen, C. I. (1998). Attachment style and emotion regulation in dementia patients and their relation to caregiver burden. The Journals of Gerontology Series b: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 53B(3), P147–P154. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/53B.3.P147

Maguire, R., & Maguire, P. (2020). Caregiver burden in multiple sclerosis: Recent trends and future directions. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports, 20, 1–9.

Marinaci, T., Carpinelli, L., & Savarese, G. (2021). What does anorexia nervosa mean? Qualitative study of the representation of the eating disorder, the role of the family and treatment by maternal caregivers. BJPsych Open, 7(3):e75. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.27

Martínez-Martín, P. (1998). An introduction to the concept of “quality of life in Parkinson’s disease.” Journal of Neurology, 245(Suppl 1), S2–S6. https://doi.org/10.1007/pl00007733

Martínez-Martín, P. et al. (2007). Caregiver burden in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Movement Disorders, 22, 924–931; quiz 1060.

Martinez-Martin, P., et al. (2008). Burden, perceived health status, and mood among caregivers of Parkinson’s disease patients. Journal of Movement Disorders, 23, 1673–1680.

Martinez-Martin, P., et al. (2015). Neuropsychiatric symptoms and caregiver’s burden in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 21, 629–634.

Nelis, S. M., Clare, L., & Whitaker, C. J. (2014). Attachment in people with dementia and their caregivers: A systematic review. Dementia, 13(6), 747–767. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301213485232

Novak, M., & Guest, C. I. (1989). Application of a multidimensional care-giver burden inventory. The Gerontologist, 29, 798–803.

Perren, S., Schmid, R., Herrmann, S., & Wettstein, A. (2007). The impact of attachment on dementia-related problem behavior and spousal caregivers’ well-being. Attachment & Human Development, 9(2), 163–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730701349630

Pezzati, R., Barone, L., & Mattei, M. (2005). Implicazioni dell’attaccamento nella cura dei grandi vecchi da parte delle generazioni successive. Giornale Di Gerontologia, 53(5), 542–548.

Picillo, M., et al. (2019). Validation of the Italian version of carers’ quality-of-life questionnaire for parkinsonism (PQoL Carer) in progressive supranuclear palsy. Neurological Sciences, 40, 2163–2169.

Pietromonaco, P. R., & Beck, L. A. (2019). Adult attachment and physical health. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 115–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.04.004

Poyner-Del Vento, P., Goy, E., Baddeley, J., & Libet, J. (2018). The caregivers’ attachment and relationship education class: A new and promising group therapy for caregivers of individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy, 17(2), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332691.2017.1341356

Postuma, R. B., Berg, D., Stern, M., et al. (2015). MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders, 30(12), 1591–1601. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.26424

Ransmayr, G. (2020). Caregiver burden in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Fortschritte Der Neurologie-Psychiatrie, 88, 567–572.

Ransmayr, G. (2021). Challenges of caregiving to neurological patients. Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift, 171(11–12), 282–288.

Romano, D., Karantzas, G. C., Marshall, E. M., Simpson, J. A., Feeney, J. A., McCabe, M. P., Lee, J., & Mullins, E. R. (2020). Carer burden and dyadic attachment orientations in adult children-older parent dyads. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 90, 104170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2020.104170

Romano, D., Karantzas, G. C., Marshall, E. M., Simpson, J. A., Feeney, J. A., McCabe, M. P., Lee, J., & Mullins, E. R. (2022). Carer burden: Associations with attachment, self-efficacy, and care-seeking. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 39(5), 1213–1236. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075211049435

Scharfenort, M., Timpka, J., Sahlström, T., Henriksen, T., Nyholm, D., & Odin, P. (2021). Close relationships in Parkinson’s disease patients with device‐aided therapy. Brain and Behavior, 11(6). https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.2102

Schrag, A., Hovris, A., Morley, D., Quinn, N., & Jahanshahi, M. (2006). Caregiver-burden in Parkinson’s disease is closely associated with psychiatric symptoms, falls, and disability. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 12, 35–41.

Schrag, A., Jahanshahi, M., & Quinn, N. (2000). What contributes to quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease? Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 69, 308–312.

Sillars, A., Leonard, K. E., Roberts, L. J., & Dun, T. (2002). Cognition and communication during marital conflict: How alcohol affects subjective coding of interaction in aggressive and nonaggressive couples. In P. Noller & J. A. Feeney (A c. Di), Understanding Marriage (1a ed., pagg. 85–112). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511500077.006

Sögüt, Ç., & Dündar, P. E. (2017). Evaluation of caregivers’ burden of the patients receiving home health service in Manisa. Turkish Journal of Public Health, 15(1), 37–46.

Tateo, L., Español, A., Kullasepp K., G., H., K., Marsico, G., & Palang, H. (2018). Five gazes on the border. A Collective Auto-Ethnographical Writing. Human Arenas, 1(2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42087-018-0010-1

The EuroQol Group. (1990). EuroQol-a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy, 16, 199–208.

Troisi, G., Parola, A., & Margherita, G. (2022). Italian validation of AAS-R: Assessing psychometric properties of Adult Attachment Scale—Revised in the Italian Context. Psychological Studies, 1–9.

Vidotto, G., Ferrario, S. R., Bond, T. G., & Zotti, A. M. (2010). Family Strain Questionnaire-Short Form for nurses and general practitioners. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19(1–2), 275–283.

Wardrope, A., Green, B., Norman, P., & Reuber, M. (2019). The influence of attachment style and relationship quality on quality of life and psychological distress in carers of people with epileptic and nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy & Behavior, 93, 16–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.01.028

World Health Organization (2023). Retrieved date April, 2023, from Websource: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/parkinson-disease

You, H. S., & Malley-Morrison, K. (2000). Young adult attachment styles and intimate relationships with close friends: A cross-cultural study of Koreans and Caucasian Americans. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31(4), 528–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022100031004006

Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67, 361–370.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Salerno within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C., C.R., Gi.Sa., and Gi.St.; methodology, L.C., E.T., F.P., C.R, Gi.Sa., and Gi.St.; formal analysis, L.C.; data curation E.T., F.P., L.C., C.R, Gi.Sa., and Gi.St.; writing—original draft preparation, L.C., C.R, Gi.Sa., and Gi.St.; writing—review and editing, Gi.Sa. and C.R.; visualization, M.T.P. and M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and the recommendations of the Associazione Italiana di Psicologia (AIP). This study was approved by “Asl Na3” Hospital committee referred to “San Giovanni di Dio e Ruggi d’Aragona Hospital” (Salerno, Italy) (number 130/2021).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Carpinelli, L., Savarese, G., Russo, C. et al. Caregivers’ Burden in Parkinson’s Disease: A Study on Related Features and Attachment Styles. Hu Arenas (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42087-023-00350-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42087-023-00350-w