Key summary points

To investigate the association between multimorbidity and readmission amongst patients on Transitional Aged Care Program (TACP).

AbstractSection FindingsHospital readmission rates increased with multimorbidity and the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) is independently associated with a 30-day hospital readmission in TACP cohort.

AbstractSection MessageIdentifying vulnerability to readmission, such as multimorbidity may allow future exploration of targeted interventions to optimise transitional care and individualise patient care to improve functional independence and prevent premature Residential Aged Care Facilities (RACF) admissions in older people.

Abstract

Purpose

Older patients are at high risk for poor outcomes after an acute hospital admission. The Transitional Aged Care Programme (TACP) was established by the Australian government to provide a short-term care service aiming to optimise functional independence following hospital discharge. We aim to investigate the association between multimorbidity and readmission amongst patients on TACP.

Methods

Retrospective cohort study of all TACP patients over 12 months. Multimorbidity was defined using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), and prolonged TACP (pTACP) as TACP ≥ 8 weeks.

Results

Amongst 227 TACP patients, the mean age was 83.3 ± 8.0 years, and 142 (62.6%) were females. The median length-of-stay on TACP was 8 weeks (IQR 5–9.67), and median CCI 7 (IQR 6–8). 21.6% were readmitted to hospital. Amongst the remainder, 26.9% remained at home independently, 49.3% remained home with supports; < 1% were transferred to a residential facility (0.9%) or died (0.9%). Hospital readmission rates increased with multimorbidity (OR 1.37 per unit increase in CCI, 95% CI 1.18–1.60, p < 0.001). On multivariable logistic regression analysis, including polypharmacy, CCI, and living alone, CCI remained independently associated with 30-day readmission (aOR 1.43, 95% CI 1.22–1.68, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

CCI is independently associated with a 30-day hospital readmission in TACP cohort. Identifying vulnerability to readmission, such as multimorbidity, may allow future exploration of targeted interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

During hospitalisation, older people are at risk of significant functional decline, which may impair their future independence and quality of life [1], and a recent Australian paper noted that in-hospital functional decline occurred in two thirds of patients [2]. Loss of independence in these activities is strongly associated with institutionalization, caregiver burden, higher resource use, and death [1, 3]. High readmission rates may be a marker of poor quality of care [4] as well as an economic burden [5]. With increasing numbers of older people admitted to hospital, there comes too the need to facilitate efficient discharge planning, aiming to prevent long hospital admissions, premature permanent Residential Aged Care Facilities (RACF) admissions and reduce hospital readmissions.

The prevalence of multimorbidity in older populations is high; amongst Australians aged 65 years or older, 60% have two or more chronic conditions [6]; this is not dissimilar to other regions [7]. Multimorbidity is associated with more complex health needs, prolonged acute hospital admissions and increased frequency of readmissions [8, 9]. It may thus be intuitive that patients with multimorbidity might benefit from coordinated and continuing care post-discharge, with a focus on functional restoration.

The Transitional Aged Care Programme (TACP) was established by the Australian government in 2005 to provide short-term support and post-acute rehabilitation for people aged 65 years or older at discharge from acute/subacute care to home [10]. Although there is no established transitional care programme in Europe, studies are currently being conducted to assess the outcomes of transitional care programmes [11] and a recent multicentre randomised trial conducted in the Netherlands observed that acutely hospitalised older patients > 65 years old who received a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) combined with transitional care had lower 1-month and 6-month mortality rates compared to those who receive CGA alone [12]. Transitional care is short-term care whose aim is to optimise an older person’s function and independence following hospital discharge. TACP provides a community based, case-managed, goal-orientated and time-limited, flexible package of services including physical therapy and personal or home care services provided by a multidisciplinary team. TACP is usually delivered at a recipient’s home and is initially approved for up to 12 weeks, with a 6-week extension possible. According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, the average duration of transitional care is 60 days [10].

Transitional care between hospital and home have been shown to be effective in improving patient’s functional status and allowing older patients to remain home after an acute hospital admission, in Australia and elsewhere [12,13,14]. Cations et al. [15] found that for all older Australians accessing TACP between 2007 and 2015, functional independence improved from entry to discharge for almost 4 in 10 people, with 50% of TACP users were able to remain home after 6 months. Entry to permanent care was more common with older age, higher levels of frailty and those with dementia. The effectiveness of TACP was further highlighted in a study of 369 patients who underwent residential TACP, almost 70% were able to return home [16].

The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) is the most frequently used tool to measure co-existing disease and has been validated in the older population as a predictor of mortality [17, 18]. Higher CCI scores are associated with increased readmission rate following discharge from hospital as evident in patients following orthopaedic surgery [19] and has been associated with increasing dependence and frailty [20]. Composite measures including the CCI have been investigated for increased ability to predict the risk of death or unplanned readmissions within 30 days after hospital discharge [21]. Other patient factors may also be associated with increased likelihood of readmission within a 30 day period, across various groups, and most not particular to patients availing of TACP. These include social isolation, polypharmacy (defined as ≥ 5 medications), and a variety of specific medical conditions, such as osteoarthritis and dementia [22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Frailty itself may also be associated with increased hospital readmission within 30 days [29, 30]. Many of these factors are indeed associated with a plethora of adverse outcomes beyond readmission, including emergency admissions, hospital length-of-stay, and mortality [31]. Looking specifically at TACP cohorts, a New Zealand group identified that poorer functional status and comorbidity burden were associated with readmission where readmission rates were high at 42% [32]. The intervention structure may also affect outcome. Nonetheless, a review of the literature highlights several evidence gaps in terms of outcomes in patients receiving transitional care [15].

In this context, we sought to identify whether multimorbidity, as determined by CCI, was associated with an increased risk of 30 day hospital readmission while in receipt of transition care at home, and whether associated with duration of needing TACP.

Methodology

Inclusion criteria and admission to TACP

We conducted a retrospective observational study of all patients discharged from an in-patient setting to a single-centre Transitional Aged Care Programme (TACP), in Sydney, for the year July 2013–June 2014 inclusive. Patients were admitted to this programme from a tertiary university teaching hospital in New South Wales (NSW), Australia, and to a lesser extent from the local rehabilitation (subacute) hospital and other nearby hospitals (public/private). Patients were referred by their in-patient team once medically well and stable for transfer to the community but identified as requiring ongoing involvement of at least 2 allied health disciplines to optimise their community reengagement. Patients were identified as potentially suitable for TACP by the treating multidisciplinary team, in consultation with a geriatrician, and referred to the local Aged Care Assessment Team (ACAT). ACAT uses standardised eligibility criteria to determine whether a person is suitable for TACP, including that they are currently an in-patient, able to enter the care programme within 24–48 h of discharge, and who are deemed likely to benefit from goal-oriented, time-limited care and support in a non-hospital environment to “complete their restorative process, optimise their functional capacity, and finalise and access their longer term care arrangements” [10].

Length-of-stay on TACP was determined by the TACP team, based on achievement of pre-defined individualised rehabilitation goals; when these were reached, patients were discharged from the programme.

Data sources and variables

Patient electronic notes and TACP databases were reviewed to identify patient demographics, multimorbidity, functional independence, medications, length-of-stay on TACP, and readmission (to an acute hospital) within 30 days. Primary diagnoses were determined by the treating medical team. The primary outcome measure was 30-day readmission (to an acute hospital), with length-of-stay on TACP programme and prolonged TACP admission as secondary outcome measures.

Community discharge supports at time of exit from the TACP were ordered according to the level of support offered, and analysed as an ordinal variable, from independent living (no additional formal supports), those at home with formal supports (eg: government funded homecare packages or private carers) and to those requiring residential care.

Definition of multimorbidity

Functional independence was measured using the Barthel index (score out of 100) which was performed by the TACP therapist. The CCI was used to measure burden of disease. Data from each patient’s chart was entered into the CCI table to formulate a numerical result. We defined high CCI as CCI in the highest quartile (CCI > 9).

Musculoskeletal disorder included any patients with osteoporosis, osteoarthritis or gout.

Gait disorder included any patient with a history of falls, or requiring a walking aid as documented by physiotherapist of the treating medical team. This included patients whose primary diagnosis (eg: fall with a fractured pelvis) resulted in the need of a walking aid at discharge. Cognitive impairment was documented if a score of 26 or below was recorded in medical notes from formal cognitive testing using the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) or similar screening tool. Mental health disorders included the documentation of depression, or other psychiatric illnesses. Social supports were identified on the initial assessment by TACP case manager. Polypharmacy was defined as receiving > 5 medications on admission to TACP.

Gait disorder referenced any TACP patient documented to have had a fall or using a walking aide as documented on discharge. 'Gait disorder' was diagnosed by the treating TACP physiotherapist, and based on history and examination, including the use of standardised objective measures (Timed up and Go, 10 Metre walk test, 6 Minute Walk Test and included gait disorders of varying aetiology and phenotype [33].

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was readmission to the acute hospital. Only index admissions to TACP were included. Secondary outcome measures included prolonged TACP (pTACP), defined as ≥ 8 weeks on the TACP programme, and level of support needed at discharge from TACP. We also recorded patient death.

Formal services were defined as paid/funded support social/health services, beyond ‘informal’ (unpaid) care by family/friends. Gait disorder was captured as present where diagnosed by the treating TACP team (who specifically collected this information) and cognitive impairment included a medical diagnosis of dementia, mild cognitive impairment or cognitive impairment not otherwise specified.

TACP covers all of Australia, but is broken up into local service providers, based on geographical area. Since its inception in 2005/6 to 2017/18, nationally, over 187,000 care recipients had received TACP, with 25,113 transitional aged care recipients in 2017/18 [34]. The TACP service within St Vincent’s Health Network Sydney is located in the geographical boundaries of the South Eastern Sydney and Western Sydney Local Health Districts. This TACP team services a catchment area which was home to > 38,000 people aged ≥ 65 at that time.

Statistical analysis

Association between outcomes (dichotomised) and variables of interest were analysed using logistic regression analysis. Independent variables were considered for inclusion in the models if biologically plausible and/or supported by the available literature and available within our data sources. Variables which were associated with outcome on univariate analysis were included in a multivariable model. Variables which were components of the CCI were excluded from models including the CCI score, to avoid collinearity [17, 18]. For multivariable analysis, an a priori strategy was used, where factors strongly associated with outcome in the existing literature were included in the multivariable model, even where they did not reach statistical significance in our own univariate analysis, unless they were collinear (correlation coefficient ≥ 0.5) with other included variables. Characteristics shown in Table 2 were included in univariate analyses (including age, sex, referral source, morbidities detailed, polypharmacy, living situation, social supports). While select morbidities were analysed (mental health disorder, musculoskeletal disorder, gait disorder, cognitive impairment), variables included in the CCI were not otherwise extracted for individual analysis. To determine whether the CCI may be helpful in predicting 30-day readmission, we employed the Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC) curve test.

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata v13.0.

Ethical approval

This study was approved as a Low to Negligible Risk project by St Vincent’s Human Research Ethics Committee (SCH14/029), and the need for individual patient consent was waived.

Results

Overall, 227 patients received TACP upon discharge from hospital in the year July 2013–June 2014, and were eligible for inclusion. No variables for investigation were missing, and no patients were lost to follow-up. Overall, the mean age was 83.3 ± 8.0 years, and 142 (62.6%) were female. A third (32.2%) had documented formal services prior to admission. Principal diagnosis for initial hospital admission were categorised into systems groups as shown in Table 1. ‘Musculoskeletal and mobility problems’ comprised the commonest diagnostic group, most often consisting of a fall. In total, 80/227 (45.2% of whole group) patients presented with fall, and over half of these (49/80) were admitted with fall and associated fracture. The commonest cardiorespiratory problem was lower respiratory tract infection/pneumonia (N = 18) followed by CCF (N = 5). The majority of patients were admitted to TACP from the acute public hospital, with the distribution of ward sources shown in Table 2, with a further 20% from the local rehabilitation hospital, and a smaller proportion from private hospitals.

Multimorbidity are shown in Table 2. Evidence of a gait disorder was very common, present in 9/10 patients, and over half had cognitive impairment. Polypharmacy was evident in 92% (207/227) of patients. Mean number of medications on admission to the TACP was 9.8 (SD 4.2).

At admission to TACP, over a third of the cohort lived with someone, and less than a third of the cohort lived alone without major support from family/friends (Table 2). The admission to TACP Barthel Index mean was 80.1 (SD 14.5) and mean Barthel Index at discharge from TACP was 92.6 (SD9.5).

Rates of multimorbidity were high. The median CCI for all patients was 7 (IQR 6–8) and 10% of patients had a CCI ≥ 11. Highest quartile of CCI was identified as CCI > 9.

Patient outcomes

Median length-of-stay for all patients on TACP was 8 weeks (IQR 5–9.67). Overall, 37.9% of the total participants required prolonged TACP (≥ 8 weeks).

Just over 1 in 5 (22.0%, 50/227) of the TACP participants were readmitted within 30 days of discharge. These patients were automatically discharged from TACP at the time of hospital readmission.

Amongst those who were not readmitted, outcomes at the end of TACP are shown in Table 2; nearly half (49.3%) of patients remained at home with formal services, while very few died while on TACP or died (< 1% for each).

Associations with and prediction of readmission to an acute hospital whilst on TACP

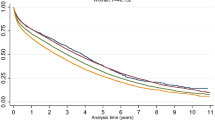

On unadjusted logistic regression analysis, each point increase in CCI was associated with a 37% increase in the odds of requiring readmission to an acute hospital (unadjusted OR 1.37 per unit increase, 95% CI 1.18–1.60, p < 0.001). Likewise, when analysed as a binary variable, the highest quartile of CCI was associated with readmission within 30 days (unadjusted OR 3.42 with CI 1.72–6.77, p < 0.001). CCI was a moderately strong predictor of readmission, with an area under the ROC curve of 0.69 (Fig. 1).

On univariate analysis, we did not observe any association between readmission and any of the other investigated variables. However, based on previous published evidence indicating a strong association between early hospital readmission and both polypharmacy and social supports, and as per our a priori statistical strategy, we included these in our final multivariable model. On multivariable logistic regression analysis, adjusting for both polypharmacy and social supports, CCI retained an independent association with 30-day readmission (aOR 1.43, 95% CI 1.22–1.68, p < 0.001) (Table 3a). Likewise, when analysing highest quartile of CCI, only high CCI (aOR 3.9, CI 1.9–8.01, p < 0.001) was independently associated with likelihood of 30-day readmission (Table 3).

Secondary analyses: associations with prolonged TACP, level of support and death

CCI score was inversely associated with prolonged TACP course (OR 0.87 per unit increase, 95% CI 0.77–0.99, p = 0.04). Those requiring more support at time of discharge from TACP had increased likelihood of pTACP (OR per increased level of support 1.72, CI 1.19–2.489, p = 0.004). While polypharmacy was not associated with pTACP on our univariate analysis, it was included in the multivariable model as per our a priori research strategy. On multivariable logistic regression analysis, in a model including CCI, polypharmacy, and social supports, CCI was no longer inversely associated with pTACP (OR 0.93, p = 0.31). Findings were unchanged when polypharmacy was excluded from the model.

On a sensitivity analysis, when patients who required readmission within 30 days were excluded, the inverse association between CCI and prolonged TACP admission was no longer observed.

CCI was not associated with level of support required on discharge from TACP. Numbers of decedents were too small (N = 2) to allow for meaningful analysis of any association between CCI and death.

Discussion

In this retrospective review of 227 consecutive patients admitted to our TACP programme, multimorbidity, as represented by the CCI, was associated with 30-day readmission to an acute hospital. This was the case when CCI was analysed either as a continuous variable or dichotomised (highest quartile versus other), and an independent association between CCI and risk of readmission remained on adjusted analysis.

While evidence suggests that multidisciplinary aged care team interventions may reduce readmission rates in older patients discharged from the emergency department or in-patient wards [35, 36], we note that in the specific group of older patients receiving transitional aged care on hospital discharge, CCI may have moderate utility in identifying those at higher risk of rehospitalisation. Our evidence, drawn retrospectively from a single TACP area, indicates that the CCI may have some utility in predicting readmission amongst those receiving multidisciplinary transitional care. The CCI is easily calculated using data routinely collected in clinical practise. The ROC curve we observed, with AUC 0.69, suggests that the CCI is moderately predictive of readmission, but is not without flaws for use as a predictive tool, and our data must be interpreted with caution. Existing algorithms have shown similar prediction values at best. The HOPE index [37], for example, developed and validated in over 3000 patients over a 24 month period, resulted in an AUC of 0.69 for mortality on ROC analysis, and AUC of 0.62 for rehospitalisation. Given data suggesting that other variables such as frailty [29], and dementia [23] are associated with readmission, a prospective study, exploring the potential increases in sensitivity and specificity if other factors are combined with CCI may be helpful in determining those at highest risk of hospital readmission.

While our initial analysis indicated that CCI was associated with lower odds of needing a longer TACP package, this signal was obviated on multivariable analysis, and when those who were readmitted were excluded. We hypothesise that this latter finding is because those with high levels of multimorbidity are at higher risk of readmission, thus cutting their TACP duration short.

Strengths of our study are the inclusion of a large cohort of otherwise unselected older persons who were admitted to our TACP programme over an entire year. We included consecutive patients, and no patients were lost to follow-up. In an unselected group of emergency department patients aged ≥ 75, a Sydney group noted 30-day readmission rates of only 17% in the group randomised to comprehensive geriatric assessment and 28-day multidisciplinary intervention [35]. Our TACP patients tend to represent the more vulnerable end of the community-dwelling aged population, and rates of multimorbidity were high; they were also transferring to TACP following a period of hospitalisation. A recent New Zealand study with similar numbers reported 3-month readmission rates of 42% following admission to a Community Rehabilitation, Enablement and Support (CREST) programme, similar to our TACP [32]. We did not identify any larger studies investigating factors associated with rehospitalisation in populations receiving multidisciplinary transitional aged care. Our data collection was comprehensive, with no missing relevant variables. Diagnoses and baseline multimorbidity were determined by the treating medical team and additional assessments and documentation of cognitive impairment, Barthel’s Indices, formal services, living situations, were all performed by accredited members of the TACP staff.

We acknowledge limitations of this study. This was a retrospective study for transition of care from a single-centre urban setting, where patients were discharged from either an acute hospital or in-patient rehabilitation unit to home. There may be under-reporting of some variables e.g. mental health, which were determined on history-taking and thus subject to reporting or recall biases. The data are now a few years old, and it is possible that characteristics of patients may have changed in this time period [34]. However, it retains relevance as high readmission rates are still noted in older and frail patients from programmes such as TACP through Australia and further afield [38]. Identification of vulnerabilities pre-discharged may potentially prevent further readmissions. As outlined in our results, this was a patient cohort entering a goal-orientated programme, therefore our findings in relation to readmission rates may not be necessarily generalizable to a non-TACP/rehabilitation cohort. We did not collect data identifying the causal factors prompting readmission, nor the outcomes of those patients who were readmitted such as death or transfer to permanent residential care. Heppenstall et al. found that half of readmissions amongst their CREST cohort (N = 224) were due to new acute medical problems, and a quarter due to exacerbation of chronic conditions; 86% of those who were readmitted were able to return home following hospitalisation [32]. Factors such as nutritional status [39, 40] and frailty indices [29] may be associated with adverse patient outcomes, and would have been good to include as stand-alone variables, but we did not have these data for our cohort. Finally, our mortality rates were low, precluding in-depth exploration of factors associated with death, but this is unlikely to be a frequent outcome in TACP cohorts.

It may be intuitive that higher multimorbidity might increase risk of readmission. However, to date, with the exception of that by Heppenstall et al. [32], there has been limited literature investigating the association between multimorbidity and readmission rates in patients admitted to TACP or similar community transition rehabilitation programmes. Prospective investigation of tools such as CCI, and potential refinement of predictive ability with addition of other easily accessible clinical data, may improve our ability to identify patients at highest risk of readmission, and determine whether targeted interventions can reduce risk and improve long term outcomes. This may improve the selection of patients, improve communication regarding likely outcomes with patients and their carers, and potentially allow us to better individualise care and target resources to groups most likely to benefit. This may be complimented by standardised data collection, and inclusion of readily available clinical and outcome variables in such databases.

In a moderately large group of consecutive patients admitted to TACP, we found that over 1 in 5 patients was readmitted to hospital within 30 days, and this was commoner in patients with higher levels of multimorbidity. Further study of readmission presentations may help stratify patients who may benefit further care planning prior to discharge and allow exploration of targeted interventions to reduce risk. This is important as poorly managed transitional care in older patients can lead to negative health outcomes and high costs for society. At present, findings from our current study are hypothesis-generating, but highlight vulnerability to readmission in older patients with high levels of multimorbidity receiving TACP.

References

Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, Counsell SR, Stewart AL, Kresevic D, Burant CJ, Landefeld CS (2003) Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc 51(4):451–458. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51152.x

Ni Chroinin D, Basic D, Conforti D, Shanley C (2018) Functional deterioration in the month before hospitalisation is associated with in-hospital functional decline: an observational study. Eur Geriatr Med 9(3):321–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-018-0041-7

Berian JR, Mohanty S, Ko CY, Rosenthal RA, Robinson TN (2016) Association of loss of independence with readmission and death after discharge in older patients after surgical procedures. JAMA Surg 151(9):e161689. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2016.1689

Balla U, Malnick S, Schattner A (2008) Early readmissions to the department of medicine as a screening tool for monitoring quality of care problems. Medicine (Baltimore) 87(5):294–300. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0b013e3181886f93

Fabbian F, Boccafogli A, De Giorgi A, Pala M, Salmi R, Melandri R, Gallerani M, Gardini A, Rinaldi G, Manfredini R (2015) The crucial factor of hospital readmissions: a retrospective cohort study of patients evaluated in the emergency department and admitted to the department of medicine of a general hospital in Italy. Eur J Med Res 20(1):6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-014-0081-5

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2016) Australia’s health 2016—Chronic diseases and comorbidities. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/666de2ad-1c92-4db3-9c01-1368ba3c8c98/ah16-3-3-chronic-disease-comorbidities.pdf.aspx#:~:text=Who%20experiences%20comorbidity%3F,0%E2%80%9344%20(9.7%25). Accessed 12 Mar 2022

Salive ME (2013) Multimorbidity in older adults. Epidemiol Rev 35:75–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxs009

Glans M, Kragh Ekstam A, Jakobsson U, Bondesson A, Midlov P (2020) Risk factors for hospital readmission in older adults within 30 days of discharge—a comparative retrospective study. BMC Geriatr 20(1):467. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01867-3

Wolff JL, Starfield B, Anderson G (2002) Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 162(20):2269–2276. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.162.20.2269

Australian Government Department of Health (2021) Transition Care Programme Guidelines 2021. Australian Government Department of Health. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/07/transition-care-programme-guidelines.pdf. Published July 2021. Accessed 12 Mar 2022

Leithaus M, Beaulen A, de Vries E, Goderis G, Flamaing J, Verbeek H, Deschodt M (2022) Integrated care components in transitional care models from hospital to home for frail older adults: a systematic review. Int J Integr Care 22(2):28. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.6447

Buurman BM, Parlevliet JL, van Deelen BA, de Haan RJ, de Rooij SE (2010) A randomised clinical trial on a comprehensive geriatric assessment and intensive home follow-up after hospital discharge: the transitional care bridge. BMC Health Serv Res 29(10):296. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-10-296

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2014) Transition care for older people leaving hospital 2005–06 to 2012–13. Aged care series. no. 40. Cat. no. AGE 75. Canberra: AIHW. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/ca981886-a4ae-453e-810c-c4b03a6802eb/17513a.pdf.aspx?inline=true. Accessed 12 Mar 2022

Morkisch N, Upegui-Arango LD, Cardona MI, van den Heuvel D, Rimmele M, Sieber CC, Freiberger E (2020) Components of the transitional care model (TCM) to reduce readmission in geriatric patients: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr 20(1):345. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01747-w

Cations M, Lang C, Crotty M, Wesselingh S, Whitehead C, Inacio MC (2020) Factors associated with success in transition care services among older people in Australia. BMC Geriatr 20(1):496. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01914-z

Chan DKY, Zhang S, Liu Y, Upton C, Kurien PE, Li R, Hohenberg MI, Hung WT (2019) Effectiveness and analysis of factors predictive of discharge to home in a 4-year cohort in a residential transitional care unit. Aging Med (Milton) 2(3):162–167. https://doi.org/10.1002/agm2.12076

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40(5):373–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

Pompei P, Charlson ME, Douglas RG Jr (1988) Clinical assessments as predictors of one year survival after hospitalization: implications for prognostic stratification. J Clin Epidemiol 41(3):275–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(88)90132-1

Voskuijl T, Hageman M, Ring D (2014) Higher Charlson Comorbidity Index Scores are associated with readmission after orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res 472(5):1638–1644. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-013-3394-8

Boeckxstaens P, Vaes B, Legrand D, Dalleur O, De Sutter A, Degryse JM (2015) The relationship of multimorbidity with disability and frailty in the oldest patients: a cross-sectional analysis of three measures of multimorbidity in the BELFRAIL cohort. Eur J Gen Pract 21(1):39–44. https://doi.org/10.3109/13814788.2014.914167

Gruneir A, Dhalla IA, van Walraven C, Fischer HD, Camacho X, Rochon PA, Anderson GM (2011) Unplanned readmissions after hospital discharge among patients identified as being at high risk for readmission using a validated predictive algorithm. Open Med 5(2):e104–e111

Basnet S, Zhang M, Lesser M, Wolf-Klein G, Qiu G, Williams M, Pekmezaris R, DiMarzio P (2018) Thirty-day hospital readmission rate amongst older adults correlates with an increased number of medications, but not with Beers medications. Geriatr Gerontol Int 18(10):1513–1518. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13518

Daiello L, Gardner R, Epstein-Lubow G, Butterfield K, Gravenstein S (2012) Dementia is associated with increased risk of hospital readmission within 30 days of discharge. Alzheimers Dement 8(4):564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2012.05.1521

Dickens CM, McGowan L, Percival C, Douglas J, Tomenson B, Cotter L, Heagerty A, Creed FH (2004) Lack of a close confidant, but not depression, predicts further cardiac events after myocardial infarction. Heart 90(5):518–522. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2003.011668

Edwards MH, van der Pas S, Denkinger MD, Parsons C, Jameson KA, Schaap L, Zambon S, Castell MV, Herbolsheimer F, Nasell H, Sanchez-Martinez M, Otero A, Nikolaus T, van Schoor NM, Pedersen NL, Maggi S, Deeg DJ, Cooper C, Dennison E (2014) Relationships between physical performance and knee and hip osteoarthritis: findings from the European Project on Osteoarthritis (EPOSA). Age Ageing 43(6):806–813. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afu068

Ma C, Bao S, Dull P, Wu B, Yu F (2019) Hospital readmission in persons with dementia: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 34(8):1170–1184. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5140

UPBEAT Collaborative Group, Mistry R, Rosansky J, McGuire J, McDermott C, Jarvik L (2001) Social isolation predicts re-hospitalization in a group of older American veterans enrolled in the UPBEAT Program. Unified psychogeriatric biopsychosocial evaluation and treatment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 16(10):950–959. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.447

Sganga F, Landi F, Ruggiero C, Corsonello A, Vetrano DL, Lattanzio F, Cherubini A, Bernabei R, Onder G (2015) Polypharmacy and health outcomes among older adults discharged from hospital: results from the CRIME study. Geriatr Gerontol Int 15(2):141–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12241

Pugh JA, Wang CP, Espinoza SE, Noël PH, Bollinger M, Amuan M, Finley E, Pugh MJ (2014) Influence of frailty-related diagnoses, high-risk prescribing in elderly adults, and primary care use on readmissions in fewer than 30 days for veterans aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 62(2):291–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12656

Stillman GR, Stillman AN, Beecher MS (2021) Frailty is associated with early hospital readmission in older medical patients. J Appl Gerontol 40(1):38–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464819894926

Ofori-Asenso R, Zomer E, Chin KL, Si S, Markey P, Tacey M, Curtis AJ, Zoungas S, Liew D (2018) Effect of comorbidity assessed by the charlson comorbidity index on the length of stay, costs and mortality among older adults hospitalised for acute stroke. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(11):2532. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112532

Heppenstall CP, Chiang A, Hanger HC (2018) Readmissions to hospital in a frail older cohort receiving a community-based transitional care service. N Z Med J 131(1484):38–45

Pirker W, Katzenschlager R (2017) Gait disorders in adults and the elderly: a clinical guide. Wien Klin Wochenschr 129(3–4):81–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-016-1096-4

KPMG Department of Health (2019) Review of the Transition Care Programme. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2019/12/review-of-the-transition-care-programme-final-report_0.pdf. Accessed 30 Jan 2023

Caplan GA, Williams AJ, Daly B, Abraham K (2004) A randomized, controlled trial of comprehensive geriatric assessment and multidisciplinary intervention after discharge of elderly from the emergency department–the DEED II study. J Am Geriatr Soc 52(9):1417–1423. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52401.x

Parsons M, Parsons J, Rouse P, Pillai A, Mathieson S, Parsons R, Smith C, Kenealy T (2018) Supported Discharge Teams for older people in hospital acute care: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 47(2):288–294. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afx169

Abbatecola AM, Spazzafumo L, Corsonello A, Sirolla C, Bustacchini S, Guffanti E (2011) Development and validation of the HOPE prognostic index on 24-month posthospital mortality and rehospitalization: Italian National Research Center on Aging (INRCA). Rejuvenation Res 14(6):605–613. https://doi.org/10.1089/rej.2011.1171

Fonss Rasmussen L, Grode LB, Lange J, Barat I, Gregersen M (2021) Impact of transitional care interventions on hospital readmissions in older medical patients: a systematic review. BMJ Open 11(1):e040057. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040057

Agarwal E, Ferguson M, Banks M, Batterham M, Bauer J, Capra S, Isenring E (2013) Malnutrition and poor food intake are associated with prolonged hospital stay, frequent readmissions, and greater in-hospital mortality: results from the Nutrition Care Day Survey 2010. Clin Nutr 32(5):737–745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2012.11.021

Lim SL, Ong KC, Chan YH, Loke WC, Ferguson M, Daniels L (2012) Malnutrition and its impact on cost of hospitalization, length of stay, readmission and 3-year mortality. Clin Nutr 31(3):345–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2011.11.001

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Transitional Aged Care Program (TACP) team at St Vincent’s Hospital who provided patient care and the original dataset.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. No specific funding received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

Nil to declare.

Ethical approval

This study was approved as a Low to Negligible Risk project by St Vincent’s Human Research Ethics Committee (SCH14/029), and the need for individual patient consent was waived.

Informed consent

For this type of study, consent is not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Griffin, O., Li, T., Beveridge, A. et al. Higher levels of multimorbidity are associated with increased risk of readmission for older people during post-acute transitional care. Eur Geriatr Med 14, 575–582 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-023-00770-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-023-00770-5