Key summary points

To investigate whether psychosocial resources are associated with survival among non-robust community-dwelling older Finnish people during an 18-year follow-up.

AbstractSection FindingsPsychosocial resources, such as good self-rated health and regularly visiting other people, were significantly associated with better survival of non-robust older people.

AbstractSection MessageIt is important to focus also on psychological well-being, together with physical activity and nutrition, of frail older people to remain or promoting their capacity.

Abstract

Purpose

Psychosocial resources have been considered to be associated with survival among frail older adults but the evidence is scarce. The aim was to investigate whether psychosocial resources are related to survival among non-robust community-dwelling older people.

Methods

This is a prospective study with 10- and 18-year follow-ups. Participants were 909 non-robust (according to Rockwood’s Frailty Index) older community-dwellers in Finland. Psychosocial resources were measured with living circumstances, education, satisfaction with friendship and life, visiting other people, being visited by other people, having someone to talk to, having someone who helps, self-rated health (SRH) and hopefulness about the future. To assess the association of psychosocial resources for survival, Cox regression analyses was used.

Results

Visiting other people more often than once a week compared to that of less than once a week (hazard ratio 0.61 [95% confidence interval 0.44–0.85], p = 0.003 in 10-year follow-up; 0.77 [0.62–0.95], p = 0.014 in 18-year follow-up) and good SRH compared to poor SRH (0.65 [0.44–0.97], p = 0.032; 0.68 [0.52–0.90], p = 0.007, respectively) were associated with better survival in both follow-ups. Visiting other people once a week (compared to that of less than once a week) (0.77 [0.62–0.95], p = 0.014) was only associated with better 18-year survival.

Conclusions

Psychosocial resources, such as regularly visiting other people and good self-rated health, seem to be associated with better survival among non-robust community-dwelling Finnish older people. This underlines the importance of focusing also on psychosocial well-being of frail older subjects to remain or promote their resilience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Frailty is defined as a geriatric syndrome involving heightened vulnerability to stressors due to lowered physiological reserve and impairments in multiple systems. Frailty predicts adverse outcomes, such as falls, hospitalization, institutionalization and increased risk of death [1].

Psychosocial resources, contributors of resilience, have been considered to be related with the association between frailty and adverse outcomes [2, 3]. Psychological resources motivate healthy self-care behavior and promote resilience which does not only prevent frailty but also attenuate or reverse its negative effects [4, 5] by helping frail older adults to cope with stressful life events and maintain or initiate healthy behavior [5,6,7].

So far, the evidence of the moderating effect of psychosocial resources in the pathway from frailty to adverse outcome, such as mortality, is scarce and results vary between studies among community-dwelling older adults [8]. In the study of Op het Veld et al. [8], no moderating effects of resources, such as educational level, income, availability of informal care, living situation, sense of mastery and self-management abilities, were found on mortality among 2420 community-dwelling pre-frail and frail older Dutch people during the 2-year follow-up. In another Dutch study [9], 1665 mostly non-frail older adults were followed up for three years but no significant interaction effects between frailty and psychosocial resources (sense of mastery, self-efficacy, instrumental support and emotional support) for mortality were found. Follow-up periods of earlier studies have been short, and, therefore, studies with longer follow-ups are needed.

The aim of this study was to investigate whether psychosocial resources are related to survival among non-robust community-dwelling older Finnish people during an 18-year follow-up.

Material and methods

Study population

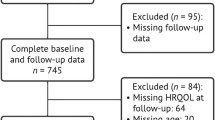

Subjects of this study were 1260 (82% of those invited) older adults (aged ≥ 64 years) living in the municipality of Lieto in Southwest Finland who participated in the longitudinal population-based epidemiological study, The Lieto Elderly Study, in 1998–99 [10]. Subjects living in institutional care (n = 65) or in sheltered housing (n = 18), with missing data of frailty (n = 51) or being robust (n = 217) were excluded from the analyses, leaving 909 non-robust (642 pre-frail and 267 frail) community-dwelling older subjects who were followed up for survival during an 18-year follow-up.

Frailty

Frailty was assessed with Rockwood’s Frailty Index (FI) which consists of at least 30 deficits, such as symptoms, signs, and disabilities which are readily available in survey or clinical data [11]. Deficits of FI used in this study are seen in Table 1.

Psychosocial resources

Measures of psychosocial resources used in this study were living circumstances (1. living with someone, 2. living alone), education (1. at least basic education, less than basic education), satisfaction with friendships (1. satisfied, 2. rather satisfied, 3. rather disappointed or no friends), satisfaction with life (1. very satisfied, 2. satisfied, 3. somehow satisfied, disappointed or very disappointed), visiting other people (1. more than once a week, 2. once a week, 3. less than once a week), being visited by other people (1. more than once a week, 2. once a week, 3. less than once a week), having someone to talk to about anything (1. yes, 2. no), having someone who helps when needed (1. yes, 2. no), self-rated health (1. good, 2. moderate, 3. poor), and hopefulness about the future (1. often or always, 2. sometimes, seldom or never).

Survival

Survival status of all participants until the end of December 2016 was obtained from the official Finnish Cause of Death Registry using unique personal identification numbers.

Ethics

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Southwest Finland approved the study protocol. Participants provided written informed consent for the study.

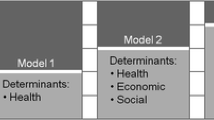

Statistical analyses

Associations of age, gender, level of frailty and psychosocial variables with survival in 10- and 18-year follow-ups were examined with univariate Cox regression analysis. Proportional hazards assumptions were evaluated with martingale residuals. The follow-up periods were calculated from the baseline measurements to the date of death or to the end of the follow-up periods. Age-, gender- and level of frailty-adjusted multivariable Cox regression model included all psychosocial variables significantly (p < 0.05) associated with survival in univariate analyses. The adjusted interaction of gender and psychosocial variables as well as age and psychosocial variables was also tested to evaluate the modifying effect of gender and age on survival. No multicollinearity was found between explanatory variables (all correlations r < 0.40). The results were quantified by calculating hazard ratios (HR) with their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS System for Windows, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The mean age of 909 non-robust community-dwelling participants was 73.2 (SD 6.4, range 64.0–97.0) years, and 541 (60%) were women. Baseline characteristics of the participants are seen in more detail in Table 2.

Survival

After the 10-year follow-up period, 63% of the participants, 57% of men and 67% of women, were alive. Corresponding proportions after the 18-year follow-up were 29%, 25% and 32%, respectively. The main causes of death were ischemic heart disease (ICD-10 codes I20–I25) (28%), cancer (C00–C97) (17%), dementia (F00–F03, G30) (16%), and cerebral insult (stroke [I63–I69, G45] 8%; hemorrhage [I60–I62] 3%) (11%).

Psychosocial resources related to survival

In univariate analyses, age, gender, level of frailty and psychosocial factors such as living with someone, being satisfied or rather satisfied with friendships, being satisfied with life, visiting other people more than once a week or at least once a week, good or moderate self-rated health and hopefulness about the future were significantly associated with better survival both in 10- and 18-year follow-ups. Higher level of basic education was associated with better survival only in the 18-year follow-up (Table 3).

In multivariable analyses adjusted for age, gender and the level of frailty, visiting other people more than once a week (compared to that of less than once a week) and good self-rated health (compared to poor self-rated health) were associated with better survival both in 10- and 18-year follow-ups (Table 4). Visiting other people once a week (compared to that of less than once a week) was only associated with better 18-year survival.

We also tested the interaction of gender and psychosocial resources as well as the interaction of age and psychosocial resources to evaluate the modifying effects of gender and age on survival (data not shown). The age- and the level of frailty-adjusted association of gender and psychosocial resources did not significantly differ between men and women either in 10- or 18-year follow-up. Significant interaction between age and basic education (adjusted with gender and the level of frailty) was found in 18-year follow-up (p = 0.038): higher education level predicted better survival in women (HR 0.62, 95% CI 0.40–0.97, p = 0.035) but not in men (0.77, 0.49–1.20, p = 0.245) during the 18-year follow-up.

Discussion

In our study, not only lower age and lower level of frailty were most strongly related to better survival, but also psychosocial factors, such as living with someone, higher level of education, satisfaction with friendships, satisfaction with life, visiting other people regularly, good SRH and hopefulness about the future, were significantly related to better survival during the 10- and/or 18-year follow-ups in univariate analyses. In multivariable analyses adjusted with age, gender and the level of frailty, the association of good SRH remained significant during the 10-year follow-up; visiting other people at least on weekly basis remained significant both in 10- and 18-year follow-ups.

In earlier studies, psychosocial resources (e.g., educational level, availability of informal care, living situation, self-efficacy, instrumental support and emotional support) were neither found to moderate the effect of the level of frailty on mortality among pre-frail (77.8% of all frail subjects) and frail community-dwelling older adults during a 2-year follow-up [8] nor to buffer against mortality among community-dwelling older adults during a 3-year follow-up [9]. The inconsistency between the results of ours and those of earlier studies can probably be explained by a slightly different methodology and different psychosocial variables used and longer follow-up of our study. Also different frailty criteria were used; Fried’s phenotype model, defining frailty in physical terms, was used in the study of Op het Veld et al. [8], and cumulative deficit frailty index, a broader definition of frailty, in our study. In addition, participants in the study of Hoogendijk et al. [9] were younger than in our study and mostly non-frail. However, also in our study, majority (70.6%) of the frail participants were pre-frail as in the study of Op het Veld et al. [8].

In consistence with our results, several earlier studies have shown poor SRH being associated with higher mortality risk among general population of older adults [12,13,14,15]. In our study, also having a good SRH, compared to poor SRH, was associated with a 10-year survival but not with 18-year survival among frail older adults. Also according to the earlier studies, long-term predictive value of SRH for mortality has shown to be poorer than that of short-term among older adults [16, 17]. It has been argued that the validity of SRH is increased probably because individuals are including more objective information in their self-assessment of health [13]. On the other hand, older person defined as frail, based on objective measures, may not perceive his/herself as frail. In the study of Lucicesare et al. [18], poor SRH, measured using a 4-question SRH index, was an important predictor of mortality among robust older people but did not seem to increase mortality among frail older people.

Significant association of regularly visiting other people with survival in our adjusted multivariate analyses indicates the beneficial effects of social relationships on survival among frail older adults. In the English Longitudinal study of Ageing, lower levels of social relationships, e.g., loneliness and social isolation, were associated with premature mortality and with functional decline in older adults. Actually, the association of social relationships, e.g., loneliness, and frailty is bidirectional. Higher levels of frailty increase the likelihood of high levels of loneliness in the future [19]. Loneliness and lower level of social participation have shown to increase inactivity [20, 21] and physical frailty [19, 22] also in other studies. Although being socially active does not necessarily prevent or reduce feelings of loneliness [23], facilitating social connections could be beneficial for frail older adults. Unfortunately, according to a recent review, most interventions aimed to prevent or reduce frailty were focused on only one or two frailty markers, physical activity and/or nutrition, and seldom on psychological well-being [24]. Social factors, such as loneliness, are often challenging to modify. However, benefits have been reported from interventions promoting group activities and the use of existing public resources, such as libraries and volunteering groups, befriending, and teaching of IT skills to enable communication using internet-based activities [25]. Therefore, promotion of social, intellectual and emotional health and meaningful goals for life [26, 27] as well as a person-centered approach focusing remaining capacity [28, 29] and balancing factors for frailty [30], such as resilience [5], have been suggested for frail older adults.

The strengths of our study are the population-based sample of frail older adults, a reasonable sample size, and a long follow-up period enabling generalizability to the frail community-dwelling Finnish older population. Psychosocial measures used in this study are commonly used in Finnish population-based studies as well as in international studies. However, some limitations should be noted. First, in our study, no time-dependent covariates were used. Second, there may have been other important confounding factors, such as quality of life [27], socioeconomic status [5] and traumatic life experiences [27], which were unavailable in this study.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that psychosocial resources, visiting other people regularly and good SRH, are associated with survival among non-robust community-dwelling older people. Our findings underline the importance of focusing also on psychological well-being, together with physical activity and nutrition, of frail older people to remain or promoting their capacity.

References

Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Mo R, Rockwood K (2013) Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 381:752–762

Ament BHL, de Vugt ME, Koomen FMK, Jansen MWJ, Verhey FRJ, Kempen GIJM (2012) Resources as a protective factor for negative outcomes of frailty in elderly people. Gerontology 58:391–397

Dent E, Hoogendijk EO (2015) Psychosocial resources: moderators or mediators of frailty outcomes? J Am Med Dir Assoc 16:258–261

Lekan DA (2018) Aging, frailty, and resilience. J Psychosoc Nurs 56:2–4

Hale M, Shah S, Clegg A (2019) Frailty, inequality and resilience. Clin Med 19:219–223

Cooper R, Huisman M, Kuh D, Deeg DJH (2011) Do positive psychological characteristics modify the association of physical performance with functional decline and institutionalization? Finding from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. J Gerontol B 66:468–477

Andrew MK, Fisk JD, Rockwood K (2012) Psychological well-being in relation to frailty: a frailty identity crisis? Int Psychogeriatr 24:1347–1353

OP Het Veld LPM, Ament BHL, van Rossum E et al (2017) Can resources moderate the impact of levels of frailty on adverse outcomes among (pre-) frail older adults? A longitudinal study. BMC Geriatr 2:485. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0583-4

Hoogendijk EO, van Hout HPJ, van der Horst HE et al (2014) Do psychosocial resources modify the effects of frailty on functional decline and mortality? J Psychosom Res 77:547–551

Löppönen M, Räihä I, Isoaho R, Vahlberg T, Kivelä S-L (2003) Diagnosing cognitive impairment and dementia in primary health care—a more active approach is needed. Age Ageing 32:606–612

Song X, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K (2010) Prevalence and 10-year outcomes of frailty in older adults in relation to deficit accumulation. J Am Geriatr Soc 58:681–687

DeSalvo KB, Muntner P (2011) Discordance between physician and patient self-rated health and all-cause mortality. Ochsner J 11:232–240

Schnittker J, Bacak V (2014) The increasing predictive validity of self-rated health. PLoS ONE 9:e84933

Shen C, Schooling CM, Chan WM et al (2014) Self-rated health and mortality in a prospective Chinese elderly cohort study in Hong Kong. Prev Med 67:112–118

Falk H, Skoog I, Johansson L et al (2017) Self-rated health and its association with mortality in older adults in China, India and Latin America—a 10/66 Dementia Research Group study. Age Ageing 46:932–999

Murata C, Kondo T, Takakoshi K, Tatsua H, Toyoshima H (2006) Determinants of self-rated health: could health status explain the association between self-rated health and mortality? Arch Gerontol Geriatr 43:369–380

Lyyra T-M, Leskinen E, Jylhä M, Heikkine E (2009) Self-rated health and mortality in older men and women: a time-dependent covariate analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 48:14–18

Lucicesare A, Hubbard RE, Searle SD, Rockwood K (2010) An index of self-rated health deficits in relation to frailty and adverse outcomes in older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res 22:255–260

Gale CR, Westbury L, Cooper C (2018) Social isolation and loneliness as risk factors for the progression of frailty: the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Age Ageing 47:392–397

Shankar A, McMunn A, Banks J, Steptoe A (2011) Loneliness, social isolation, and behavioral and biological health indications in older adults. Health Psychol 30:377–385

Netz Y, Goldsmith R, Shimony T, Arnon M, Zeev A (2013) Loneliness is associated with an increased risk of sedentary life in older Israelis. Aging Ment Health 17:40–47

Etman A, Kamphuis BM, van der Cammen TJM, Burdorf A, van Lenthe FJ (2014) Do lifestyle, health and social participation mediate educational inequalities in frailty worsening? Eur J Public Health 25:345–350

Tabue Tegue M, Simo-Tabue N, Stoykova R et al (2016) Feelings of loneliness and living alone as predictors of mortality in the elderly: The PAQUID Study. Psychosom Med 78:904–909

Puts MTE, Andrew MK, Ashe MC et al (2017) Intervention to prevent or reduce the level of frailty in community-dwelling older adults: a scooping review of the literature and international policies. Age Ageing 46:383–392

Davidson S, Rossall P (2009) Evidence review: loneliness in later life. Age UK, London 2015. https://www.ageuk.org.uk/globalassets/age-uk/documents/reports-and-publications/reports-and-briefings/health--wellbeing/rb_june15_lonelines_in_later_life_evidence_review.pdf

Fillit H, Butler RN (2009) The frailty identity crisis. J Am Ger Soc 57:348–352

Freitag S, Schmidt S (2016) Psychosocial correlates of frailty in older adults. Geriatrics. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics1040026

Nicholson C, Meyer J, Flatley M, Holman C (2013) The experience of living at home with frailty in old age: a psychosocial qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud 50:1172–1179

Whitson HE, Duan-Porter W, Schmader KE, Morey MC, Cohen HJ, Colón-Emeric CS (2016) Physical resilience in older adults: systematic review and development of an emerging construct. J Gerontol A 71:489–495

Dury S, van der Vorst A, Van der Elst M et al (2018) Detecting frail, older adults and identifying their strengths: results of a mixed-methods study. BMC Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5088-3

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Turku (UTU) including Turku University Central Hospital. The Lieto Elderly study has been financially supported by the 19th February Fund of the Finnish Heart Association, the Turku Health Centre Research Fund, the Turku University Hospital Research Fund, the Academy of Finland, the Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation and the Nordic Lions Club.

Funding

The Lieto Elderly study has been financially supported by the 19th February Fund of the Finnish Heart Association, the Turku Health Centre Research Fund, the Turku University Hospital Research Fund, the Academy of Finland, the Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation and the Nordic Lions Club.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by SL, MS and TV. The first draft of the manuscript was written by SL and MS, and TV, and RI, S-LK, MW, ML, MV and LV commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval and informed consent

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Southwest Finland approved the study protocol. Participants provided written informed consent for the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lavonius, S., Salminen, M., Vahlberg, T. et al. Psychosocial resources related to survival among non-robust community-dwelling older people: an 18-year follow-up study. Eur Geriatr Med 11, 475–481 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-020-00300-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-020-00300-7