Abstract

This study aimed to identify the factors associated with health-related quality of life (HRQOL) among community-dwelling older adults. Physical and mental HRQOL were measured by the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) at baseline and follow-up. Linear regression models were used to evaluate associations between socio-demographic, health, and lifestyle factors and HRQOL. The sample included 661 participants (mean age = 77.4 years). Frailty was negatively associated with physical HRQOL (B = − 5.56; P < 0.001) and mental HRQOL (B = − 6.65; P < 0.001). Participants with a higher score on activities of daily living (ADL) limitations had lower physical HRQOL (B = − 0.63; P < 0.001) and mental HRQOL (B = − 0.18; P = 0.001). Female sex (B = − 2.38; P < 0.001), multi-morbidity (B = − 2.59; P = 0.001), and a high risk of medication-related problems (B = − 2.84; P < 0.001) were associated with lower physical HRQOL, and loneliness (B = − 3.64; P < 0.001) with lower mental HRQOL. In contrast, higher age (B = 2.07; P = 0.011) and living alone (B = 3.43; P < 0.001) were associated with better mental HRQOL in the multivariate models. Future interventions could be tailored to subpopulations with relatively poor self-reported HRQOL, such as frail or lonely older adults to improve their HRQOL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the European Union (EU), the proportion of people aged 65 and older is expected to rise substantially, from 20.6% in 2020 to 29.4% in 20501. This demographic change is primarily driven by historically low birth rates and an increased life expectancy2. Across the EU in 2018, men and women aged 65 years had an average life expectancy of 18.1 and 21.6 years respectively1. However, at age 65 years, both men and women spend approximately half of their remaining lives with limitations in functioning1. Chronic conditions such as diabetes, osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, and dementia are increasingly common among older adults3. These conditions may negatively impact an older person’s functional independence and quality of life4.

The World Health Organization defines quality of life as ‘an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns’5. Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) comprises those aspects of quality of life that relate to a person’s perception of health6. It is a key patient-reported outcome and usually includes various domains of health, such as general health, physical functioning, mental health, social functioning and role function7. HRQOL can be used to assess the impact of disease on a person’s life as well as within the general population6. An example of a generic scale that has been developed to measure HRQOL is the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12)8. The SF-12 includes eight scales yielding two summary measures: physical and mental health.

Measuring HRQOL has become an important component of public health surveillance and can be considered a valid indicator of unmet needs and intervention outcomes6. HRQOL data analysis supports the identification of subgroups with relatively poor self-reported health. Interpretation and publication of these data can help to allocate resources more efficiently and to monitor the effectiveness of community interventions5. Previous studies have identified associations between HRQOL and socio-demographic factors, including sex and lower education9,10. Furthermore, chronic conditions, frailty, low levels of physical activity, and lack of social support have been associated with poor self-reported HRQOL10,11,12,13.

Thus far, studies have shown mixed results concerning the factors associated with HRQOL. Most studies have focused on HRQOL in relation to specific diseases or subpopulations. There is a need for a comprehensive view by studying the factors associated with HRQOL in the general population. New insights into the relationships between HRQOL and risk factors (e.g. socio-demographic factors, health-related factors, and lifestyle factors) can improve tailoring interventions to subpopulations with poor self-reported health, to improve their situation and avert more severe consequences. This study aims to identify the factors associated with HRQOL among community-dwelling older adults.

Methods

Study design

The present study used baseline and follow-up data from the ‘Appropriate care paths for frail elderly people: a comprehensive model’ (APPCARE) study—a prospective cohort study funded by the European Commission, under Grant Agreement number 664689. The APPCARE study aimed to promote healthy ageing among older adults. The project has been conducted in three European sites (Rotterdam, the Netherlands; Treviso, Italy; and, Valencia, Spain). The current study used baseline and 6-months follow-up data from the Rotterdam site.

Study participants

In collaboration with the Municipality of Rotterdam, 865 community-dwelling older adults (≥ 65 years) were invited by letter to participate in the study. Participants’ eligibility for the study was assessed by an employee of the Municipality of Rotterdam by screening the Municipal Personal Records Database. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) living in the municipality of Rotterdam; (2) age 65 years or older, (3) community-dwelling (not in long-term care) at the time of recruitment, and (4) able to provide written informed consent to participate in the study. An information package, including an information sheet, informed consent form, baseline questionnaire, and prepaid envelope was sent by post to eligible citizens. Participants who returned the signed informed consent and filled in the baseline questionnaire were included in the study. After 6 months, a follow-up questionnaire similar to the baseline questionnaire was distributed by post to participants who completed the baseline measurement. Data collection took place in 2017 and 2018. The Medical Ethics Committee of Erasmus MC University Medical Center in Rotterdam declared that the rules lead down in the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (also known by its Dutch abbreviation WMO), do not apply to this research (reference number: MEC-2016-559).

Data from 840 participants who provided informed consent and filled in the baseline questionnaire were available for this study. Participants who dropped out at follow-up (n = 95) were excluded. For the analysis, participants with missing data in the outcome variable (n = 64), age (n = 20), and sex (n = 0) were excluded, resulting in 661 (78.7%) subjects included. A flow diagram of the population of analysis is presented in Fig. 1.

Measures

Physical and mental health-related quality of life (HRQOL)

The outcome measure used in this study is health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Physical and mental HRQOL were measured by the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12). Previous findings support that the SF-12 can be a reliable and valid measure to assess health-related quality of life8,14. The SF-12 covers eight health domains: general health, mental health, vitality, social functioning, role limitation due to physical health problems, role limitation due to emotional problems, bodily pain, and physical functioning. These domains are summarised in a Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS), ranging from 0 to 10014. As differences between country-specific scores are minimal, it is recommended to use the standard (U.S.-derived) scoring of the SF-12 to allow for comparison and interpretation of the data across countries8. Prior research showed that Dutch weights resemble US weights closely14. Summary scores were transformed into standard scores, with a mean score of 50 and standard deviation of 108. Higher scores represent higher quality of life. A change of 3 units or more in PCS and MCS is considered clinically meaningful15.

Socio-demographic factors

Socio-demographic characteristics assessed at baseline were included as covariates. Age was grouped into 65–79 years and ≥ 80 years. Household composition was categorised into living with others or living alone. Education level was split into two categories based on the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). ISCED level 0–5 was categorised as ‘secondary or lower’ and ISCED level 6–8 was categorised as ‘tertiary or higher’16.

Health-related factors

Baseline health indicators assessed were multi-morbidity, frailty, activities of daily living (ADL) limitations, loneliness, risk of medication-related problems, risk of malnutrition, and falls. Multi-morbidity was defined as having two or more chronic conditions4. The Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) is a validated tool to measure multi-morbidity17. A list of 13 common chronic conditions (e.g. hypertension, stroke, diabetes) was provided17. Participants indicated whether they had one or more chronic condition(s) diagnosed by a physician. Frailty was measured by the 15-item Tilburg Frailty Indicator (TFI), which has been validated among Dutch community-dwelling older adults18. The score on overall frailty ranged from 0 to 15. Participants with a total TFI-score ≥ 5 were considered frail18. ADL limitations were assessed with the Groningen Activity Restriction Scale (GARS), range 18–7219, with higher scores representing a lower independence level. ‘Activities of daily living’ (ADL) concern routine tasks that comprise everyday living. Prior research has confirmed the validity of this scale in a community-based sample19. Loneliness was evaluated by the 6-item De Jong-Gierveld Loneliness Scale, a reliable and valid measurement instrument for overall, emotional and social loneliness20. Overall loneliness scores varied between 0–1: ‘No loneliness’, 2–4: ‘Moderately intense loneliness’, and 5–6: ‘Intense loneliness’. Overall loneliness scores were dichotomised in ‘not lonely’ (score 0–1) and ‘lonely’ (score 2–6). The risk of medication-related problems was measured by the Medication Risk Questionnaire (MRQ)21. The MRQ is a validated scale that can assess polypharmacy, inappropriate prescribing and poor adherence22. Eight items of the MRQ were summed to calculate the risk of medication-related problems21. The scores were dichotomised into: ‘low risk’ (score 0–3) or ‘high risk’ (score ≥ 4) of medication-related problems22. The risk of malnutrition was assessed with the Short Nutritional Assessment Questionnaire 65+ (SNAQ65+)23 and dichotomised in ‘low risk’ and ‘high risk’. The SNAQ65+ has been validated in community-dwelling older adults and can be used to determine malnutrition23. This study used two items of the SNAQ65+: appetite and walking stairs. The item ‘mid-upper-arm circumference’ was excluded from the score calculation as this data was not available. Instead ‘unintentional weight loss’ measured by one item of the TFI was used24. If a participant lost 6 kg or more during the last 6 months or 3 kg or more in the last month, this was defined as a high risk of malnutrition. Participants with poor appetite and problems with walking stairs and no weight loss, or no indications at all for malnutrition, were categorised as low risk. Falls were self-reported by asking participants “Have you had a fall in the last 12 months?”25. Fall status was dichotomised into has ‘fallen one or more times’ versus ‘no falls’.

Lifestyle factors

Physical activity, risk of alcohol harm and smoking were included as lifestyle factors. Physical activity was assessed with one item of a validated frailty instrument for primary care (SHARE-FI)26 to report the frequency of low to moderate-level activities, such as gardening or walking. Responses were dichotomised into ‘once a week or less’ and ‘more than once a week’. Risk of alcohol harm was assessed by three items of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C), which is effective in screening high risk alcohol use among adults27. Scores range between 0 and 12, with 0 indicating the lowest and 12 the highest risk. The variable was dichotomised (≥ 3 in women and ≥ 4 in men) to indicate whether a person was at risk of alcohol abuse or dependence27. One item assessed current smoking (yes/no).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed to describe participant characteristics using mean (SD) or number of participants (%) for the total study sample. Multivariate linear regression was used to assess the association between factors and HRQOL at follow-up. Regression analyses were conducted separately for the outcome variables PCS and MCS. Unstandardized regression coefficients (B) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated for each variable. Results were considered significant at P < 0.05. After excluding participants with missing data on health-related quality of life, age and sex, the proportion of missing data for each of the other measures was below 5%. Therefore, the analysis was conducted without imputation as the impact on the results of the analysis would likely be minimal28. To evaluate whether the association between factors and health-related quality of life was modified by socio-demographic factors (age, sex, education level, household composition), an interaction term was added to the PCS and MCS model. The interaction term socio-demographic variable*associated factor was added to the linear regression model, adjusted for all the other variables. The 2-sided significance threshold, after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing, was set at (P = 0.05/46 = < 0.001)29. To assess the correlation between the independent variables a variance inflation factor (VIF) was used by performing a multi-collinearity test. Variables are highly related when a VIF value is greater than 1030. Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethical approval

The Medical Ethics Committee of Erasmus MC University Medical Center in Rotterdam waived the need for approval in the study (reference number: MEC-2016-559). All procedures performed as part of the study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. All participants provided written informed consent.

Results

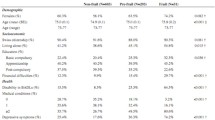

Participant characteristics

The mean age of participants was 77.4 years ± 6.0 years, and 47.2% were women. Most participants had a secondary education level or lower (78.4%). Furthermore, 492 participants (74.4%) reported having two or more health conditions (i.e. multi-morbidity). Table 1 presents the characteristics of the study population at baseline.

Factors associated with physical HRQOL

Table 2 presents the results of the univariate and multivariate linear regression models for the PCS of HRQOL. Interaction analyses revealed no statistically significant interactions for PCS (P > 0.001). For each model, the correlation between the independent variables was within acceptable limits (all VIF < 2)30. The multivariate model for PCS showed that women had a significantly worse PCS (B = − 2.38; 95% CI: − 3.68, − 1.07) compared to men. Furthermore, participants with multi-morbidity experienced a lower quality of life regarding physical HRQOL (B = − 2.59; 95% CI: − 4.17, − 1.00) compared to those with less than two health conditions. PCS was also significantly lower in participants indicated as frail (B = − 5.56; 95% CI: − 7.37, − 3.75) compared to non-frail participants. Moreover, the PCS decreased as the score on ADL limitations increased (B = − 0.63; 95% CI: − 0.72, − 0.53). Finally, participants at high risk for medication-related problems had a 2.84 (95% CI: − 4.28, − 1.40) lower physical HRQOL score compared to participants with a low risk of medication-related problems.

Factors associated with mental HRQOL

Table 3 presents the results of the univariate and multivariate linear regression models for the MCS of HRQOL. There were no statistically significant interactions for MCS (P > 0.001). For each model, the correlation between the independent variables was within acceptable limits (all VIF < 2)30. In the univariate model, participants of 80 years and older reported lower quality of life regarding the MCS compared to younger participants (B = − 1.65; 95% CI: − 3.24, − 0.06). However, when controlling for all factors in the model, higher age was associated with a 2.07 (95% CI: 0.47, 3.68) increase in MCS. Similarly, the univariate model showed a 1.34 (95% CI: − 2.90, 0.23) reduction in MCS among participants living alone, while in the multivariate model participants living alone had a significantly higher MCS (B = 3.43; 95% CI: 1.82, 5.03) compared to participants living with others. Furthermore, participants indicated as frail reported a significantly lower quality of life regarding MCS (B = − 6.65; 95% CI: − 8.69, − 4.62) compared to non-frail participants. In addition, having a higher score on ADL limitations was significantly associated with reduced MCS (B = − 0.18; 95% CI: − 0.29, − 0.07). Finally, participants classified as lonely had a significantly lower MCS (B = − 3.64; 95% CI: − 5.25, − 2.03) compared to participants who were not at risk of loneliness.

Discussion

This study aimed to identify the factors associated with health-related quality of life (HRQOL) among community-dwelling older adults. Frailty and a higher score on activities of daily living (ADL) limitations were negatively associated with both physical and mental HRQOL. Female sex, multi-morbidity, and a high risk of medication-related problems were independently associated with reduced physical HRQOL, whereas loneliness was associated with reduced mental HRQOL. In contrast, higher age and living alone were associated with better mental HRQOL in the multivariate models.

Frailty was associated with reduced physical and mental HRQOL at follow-up. This is in line with previous studies12,31,32,33. Frailty is characterised by increased vulnerability and may result in weight loss, fatigue, low levels of physical activity, and depressed mood34. Frail older adults are at increased risk of poor health outcomes resulting from falls, disability, and hospitalisation, which may negatively impact HRQOL31,34. A higher score on ADL limitations was also significantly associated with a reduced Physical Component Summary (PCS) score and Mental Component Summary (MCS) score. Due to the strong relationship between a person’s ability to perform activities and the PCS score, this result was to be expected35. Loss of muscle strength and mobility problems, especially the ability to walk, are associated with reduced physical HRQOL35,36,37. In addition, it has been shown that loss of independence in general, and dependency regarding eating, bathing and toileting specifically, is associated with a decline in mental HRQOL35,36.

Consistent with previous findings, women were more likely than men to have reduced physical HRQOL9,10,38. A possible explanation for sex differences in HRQOL is rooted in the pattern of chronic conditions. More specifically, women are more prone to musculoskeletal diseases than men39,40. Musculoskeletal conditions may contribute to pain and disability, particularly in women, and are associated with worse physical HRQOL9. Not only the type of condition but also the number of chronic conditions may negatively impact HRQOL41. Consistent with previous studies, our results showed that multi-morbidity was associated with poorer physical HRQOL39,41,42. Furthermore, the present study confirms the high risk of medication-related problems as a predictor of low physical HRQOL43,44. However, no association was found with mental HRQOL in contrast to a previous study43. In a study by Zhang et al.44, lower HRQOL was associated with polypharmacy, multi-morbidity, difficulties taking medications as prescribed, and using medications with a narrow therapeutic index. Further research is recommended to clarify the association between medication-related risk factors and HRQOL.

Participants who were classified as lonely had a lower mental HRQOL compared to participants who were not at risk of loneliness. Unlike previous research, our findings did not show an association between loneliness and physical HRQOL45,46. A study by Tan et al.46 showed a stronger association between emotional loneliness and mental HRQOL compared to social loneliness, this may suggest that older adults who miss an intimate or emotional relationship are at increased risk of poor mental HRQOL. Further research is needed to explore the factors contributing to poor mental HRQOL among older adults who are lonely. Furthermore, the univariate regression model showed that higher age (≥ 80 years) was associated with reduced mental HRQOL. In contrast, higher age was associated with increased mental HRQOL in the multivariate regression model. This result was not reported in the literature10. Gooding et al.47 suggested that older-old adults (≥ 80 years) have a better-developed capacity for resilience, particularly regarding emotional regulation and problem-solving, compared to younger-old adults (65–79 years) which could explain these findings. Moreover, the univariate model showed lower mental HRQOL among participants living alone. However, when adjusted for other variables, participants living alone had a significantly higher mental HRQOL. This finding challenges a common belief that living alone negatively impacts HRQOL48. According to Burnette et al.49, those who live alone have high levels of social interaction and participation. More specifically, living alone can have positive effects on younger-old adults and those living in urban areas. Future studies need to explore if this finding holds among various age groups and settings.

A strength of our study is the comprehensive assessment of factors, including socio-demographic, health, and lifestyle factors. In addition, we were able to maintain a relatively high response rate during follow-up. However, this study also has some limitations. First, participants were recruited by sending a participation letter, which may have resulted in selection bias with underrepresentation of vulnerable participants. Lifestyle and health behavior was assessed using a self-reported questionnaire, which may cause under- or over reporting of (un)healthy behavior. Therefore, findings must be interpreted with caution. In addition, reliance on self-reported information can lead to misclassification as participants have to recall events. Objectively measured outcomes can be used to confirm our findings. Second, some variables were collapsed into dichotomous categories, which may have resulted in loss of information. Future studies are recommended to explore factors, including frailty, loneliness and malnutrition, in more detail, particularly regarding their social dimension. These factors may have a considerable effect on the association between age and HRQOL, and living alone and HRQOL. Finally, due to the limited observation time of 6 months between baseline and follow-up, a causal relationship cannot be inferred. Further research, including multiple follow-up measurements, is required to confirm the direction of the associations. Finally, the possibility of generalisation to other cultural contexts remains unclear. Future studies need to determine whether cultural factors might change the associations observed within our study.

The results of this study confirm that HRQOL is associated with multiple factors, including socio-demographic, health and lifestyle factors10. Longitudinal research is needed to comprehensively examine the (bi-)directional associations between factors and HRQOL over time. Future studies could assess socioeconomic status more extensively by including, for example, neighbourhood socioeconomic characteristics, socioeconomic factors earlier in life, and social support. In order to prevent morbidity in older adults, prevention strategies could focus on the role of physical activity in perceived quality of life50. Previous studies showed an association between maintaining a good physical condition and a better quality of life and cognitive function50,51. The findings of this study imply that future interventions targeting health and autonomy promotion among community-dwelling older adults could be tailored to subpopulations with relatively poor self-reported HRQOL, such as frail or lonely older adults. Additional research is needed to extend our knowledge of the factors related to HRQOL in older (pre)frail adults. This information can be useful for clinicians working with older people to identify those at risk of reduced quality of life and to target interventions accordingly.

Conclusion

Our findings expand evidence from previous cross-sectional studies indicating an association between higher age, female sex, living alone, multi-morbidity, frailty, a higher score on activities of daily living (ADL) limitations, loneliness, a high risk of medication-related problems and HRQOL. The results of this study show the importance of socio-demographic characteristics in relation to HRQOL, encouraging a better collaboration between health and social care services. Further longitudinal research is needed to confirm our findings and understand the role of frailty in the relationship between risk factors and HRQOL.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

European Union. Ageing Europe - Looking at the lives of older people in the EU https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-statistical-books/-/ks-02-20-655 (2020).

Beard, J. et al. The World report on ageing and health: A policy framework for healthy ageing. Lancet 387, 2145–2154. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00516-4 (2016).

Li, Z. et al. Aging and age-related diseases: From mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Biogerontology 22, 165–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10522-021-09910-5 (2021).

Johnston, M., Crilly, M., Black, C., Prescott, G. & Mercer, S. Defining and measuring multimorbidity: A systematic review of systematic reviews. Eur. J. Public Health 29, 182–189. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cky098 (2019).

World Health Organization. The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc. Sci. Med. 41, 1403–1409. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00112-k (1995).

Wilson, I. & Cleary, P. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA 273, 7 (1995).

Guyatt, G., Feeny, D. & Patrick, D. Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann. Intern. Med. 118, 622–629. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-118-8-199304150-00009 (1993).

Ware, J. J., Kosinski, M. & Keller, S. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med. Care 34, 14. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003 (1996).

Orfila, F. et al. Gender differences in health-related quality of life among the elderly: The role of objective functional capacity and chronic conditions. Soc. Sci. Med. 63, 2367–2380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.017 (2006).

Siqeca, F. et al. Factors associated with health-related quality of life among home-dwelling older adults aged 75 or older in Switzerland: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 20, 166. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-022-02080-z (2022).

Barnett, K. et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: A cross-sectional study. Lancet 380, 37–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2 (2012).

Kojima, G., Iliffe, S., Jivraj, S. & Walters, K. Association between frailty and quality of life among community-dwelling older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 70, 716–721. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2015-206717 (2016).

Zhang, X. et al. Longitudinal association between physical activity and health-related quality of life among community-dwelling older adults: A longitudinal study of Urban Health Centres Europe (UHCE). BMC Geriatr. 21, 521. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02452-y (2021).

Gandek, B. et al. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: Results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 51, 9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00109-7 (1998).

Diaz-Arribas, M. et al. Minimal clinically important difference in quality of life for patients with low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 42, 1908–1916. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000002298 (2017).

UNESCO. International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) https://uis.unesco.org/en/topic/international-standard-classification-education-isced (2011).

Linn, B., Linn, M. & Gurel, L. Cumulative illness rating scale. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 16, 622–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1968.tb02103.x (1968).

Gobbens, R. J., Boersma, P., Uchmanowicz, I. & Santiago, L. M. The Tilburg Frailty Indicator (TFI): New evidence for its validity. Clin. Interv. Aging 15, 265–274. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S243233 (2020).

Suurmeijer, T. et al. The Groningen Activity Restriction Scale for measuring disability: Its utility in international comparisons. Am. J. Public Health 84, 1270–1273 (1994).

De Jong Gierveld, J. & Van Tilburg, T. A 6-Item scale for overall, emotional, and social loneliness: Confirmatory tests on survey data. Res. Ageing 28, 582–597. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027506289723 (2006).

Barenholtz Levy, H. Self-administered medication-risk questionnaire in an elderly population. Ann. Pharmacother. 37, 982–987. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1C305 (2003).

Levy, H. & Steffen, A. Validating the medication risk questionnaire with family caregivers of older adults. Consult. Pharm. 31, 329–337. https://doi.org/10.4140/TCP.n.2016.329 (2016).

Wijnhoven, H. A. et al. Development and validation of criteria for determining undernutrition in community-dwelling older men and women: The Short Nutritional Assessment Questionnaire 65+. Clin. Nutr. 31, 351–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2011.10.013 (2012).

Borkent, J. W., Keller, H., Wham, C., Wijers, F. & de van der Schueren, M. A. E. Cross-country differences and similarities in undernutrition prevalence and risk as measured by SCREEN II in community-dwelling older adults. Healthcare (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8020151 (2020).

Yardley, L. et al. Development and initial validation of the Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I). Age Ageing 34, 614–619. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afi196 (2005).

Romero-Ortuno, R., Walsh, C. D., Lawlor, B. A. & Kenny, R. A. A frailty instrument for primary care: findings from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). BMC Geriatr. 10, 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-10-57 (2010).

Bush, K., Kivlahan, D. R., McDonell, M. B., Fihn, S. D. & Bradley, K. A. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Arch. Intern. Med. 158, 7 (1998).

Jakobsen, J. C. et al. When and how should multiple imputation be used for handling missing data in randomised clinical trials—A practical guide with flowcharts. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 17, 162. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0442-1 (2017).

Knol, M. J. & VanderWeele, T. J. Recommendations for presenting analyses of effect modification and interaction. Int. J. Epidemiol. 41, 514–520. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyr218 (2012).

Myers, R. H. Classical and Modern Regression with Applications 2nd edn. (PWS-KENT, 1990).

Andrade, J., Drumond Andrade, F., de Oliveira Duarte, Y. & Bof de Andrade, F. Association between frailty and family functionality on health‑related quality of life in older adults. Qual. Life Res. 29, 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02433-5 (2020).

Crocker, T. et al. Quality of life is substantially worse for community-dwelling older people living with frailty: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Qual. Life Res. 28, 2041–2056. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02149-1 (2019).

Zhang, X. et al. Association between physical, psychological and social frailty and health-related quality of life among older people. Eur. J. Public Health 29, 936–942. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz099 (2019).

Fried, L., Ferrucci, L., Darer, J., Williamson, J. & Anderson, G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: Implications for improved targeting and care. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 59, 9. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/59.3.m255 (2004).

Fagerström, C. & Borglin, G. Mobility, functional ability and health-related quality of life among people of 60 years or older. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 22, 8. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03324941 (2010).

Lyu, W. & Wolinsky, F. The onset of ADL difficulties and changes in health-related quality of life. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 15, 217. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0792-8 (2017).

Samuel, D., Rowe, P., Hood, V. & Nicol, A. The relationships between muscle strength, biomechanical functional moments and health-related quality of life in non-elite older adults. Age Ageing 41, 224–230. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afr156 (2012).

Kirchengast, S. & Haslinger, B. Gender differences in health-related quality of life among healthy aged and old-aged Austrians: Cross-sectional analysis. Gend. Med. 5, 270–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genm.2008.07.001 (2008).

Larsen, F., Pedersen, M., Friis, K., Glumer, C. & Lasgaard, M. A latent class analysis of multimorbidity and the relationship to socio-demographic factors and health-related quality of life. A national population-based study of 162,283 Danish adults. PLoS One 12, e0169426. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169426 (2017).

Nusselder, W. et al. Contribution of chronic conditions to disability in men and women in France. Eur. J. Public Health 29, 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cky138 (2019).

Lawson, K. et al. Double trouble: the impact of multimorbidity and deprivation on preference-weighted health related quality of life a cross sectional analysis of the Scottish Health Survey. Int. J. Equity Health 12, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-12-67 (2013).

Wang, L., Palmer, A., Cocker, F. & Sanderson, K. Multimorbidity and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in a nationally representative population sample: Implications of count versus cluster method for defining multimorbidity on HRQoL. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 15, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-016-0580-x (2017).

Aljeaidi, M., Haaksma, M. & Tan, E. Polypharmacy and trajectories of health-related quality of life in older adults: An Australian cohort study. Qual. Life Res. 31, 2663–2671. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-022-03136-9 (2022).

Zhang, S., Meng, L., Qiu, F., Yang, J. & Sun, S. Medication-related risk factors associated with health-related quality of life among community-dwelling elderly in China. Patient Prefer. Adherence 12, 529–537. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S156713 (2018).

Boehlen, F. et al. Loneliness as a gender-specific predictor of physical and mental health-related quality of life in older adults. Qual. Life Res. 31, 2023–2033. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-03055-1 (2022).

Tan, S. et al. The Association between Loneliness and Health Related Quality of Life (HR-QoL) among Community-Dwelling Older Citizens. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020600 (2020).

Gooding, P. A., Hurst, A., Johnson, J. & Tarrier, N. Psychological resilience in young and older adults. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 27, 262–270. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2712 (2012).

Arestedt, K., Saveman, B. I., Johansson, P. & Blomqvist, K. Social support and its association with health-related quality of life among older patients with chronic heart failure. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 12, 69–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474515111432997 (2013).

Burnette, D., Ye, X., Cheng, Z. & Ruan, H. Living alone, social cohesion, and quality of life among older adults in rural and urban China: A conditional process analysis. Int. Psychogeriatr. 33, 469–479. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610220001210 (2021).

Daimiel, L. et al. Physical fitness and physical activity association with cognitive function and quality of life: Baseline cross-sectional analysis of the PREDIMED-Plus trial. Sci. Rep. 10, 3472. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59458-6 (2020).

de Sire, A. et al. Role of physical exercise and nutraceuticals in modulating molecular pathways of osteoarthritis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(11), 5722. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22115722 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the clinicians of the four hospitals involved in the APPCARE project (Erasmus MC University Medical Center, Havenziekenhuis, Amphia, and Vlietland) who enthusiastically collaborated to include participants for this study. We would also like to thank all participants for their time and energy to take part in the study.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Commission, Grant/Award Number: 664689.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ELSB, AG, HR contributed to the study conception and design. ELSB prepared the data, performed all statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. SST and FMR contributed to the data collection. EP and TAB obtained funding for the APPCARE project. All authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bally, E.L.S., Korenhof, S.A., Ye, L. et al. Factors associated with health-related quality of life among community-dwelling older adults: the APPCARE study. Sci Rep 14, 14351 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64539-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64539-x

- Springer Nature Limited