Abstract

This research project explores how upper-middle-class private school pupils are socialised into and through sports. Particularly around major sporting events such as the Olympics, there has often been commentary in the mass media regarding the extent to which former private school pupils tend to be overrepresented in Team GB within many elite-level sports. However, a need remains to research the experiences and underpinning processes that contribute to the sporting participation patterns of private school students. Semi-structured interviews were conducted to explore private school pupils’ lived experiences and better understand how they are socialised into and through sports. Primary socialisation within the family and secondary socialisation within primary school, private school, and other external agents such as sports clubs were discussed. The research findings show that an individual’s sporting habitus is not static but changes and develops throughout their lifetime depending upon the ‘fields’ they are exposed to. Pierre Bourdieu’s (1984) theoretical ideas relating to [(Habitus) (Capital)] + Field = Practice proved helpful in enabling the research to conceptualise and interpret how parental and family upbringing shaped this relationship and, therefore, provides the theoretical lens used to analyse this phenomenon. Participants demonstrated a robust sporting habitus, regularly engaging in sports and physical activity inside and outside school. The social class background of an individual affects the volumes of economic, social, cultural and physical capital they possess. Members of the upper-middle classes, therefore, seek to invest in developing different forms of capital for their children linked to the sporting ‘tastes’ and ‘distinctions’ of their class (Bourdieu, 1984).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The role of private schools and how their pupils have often dominated many elite-level sports in the United Kingdom (UK) is a topic that has been a source of critique and debate for years. Some have suggested that the London 2012 Olympics highlighted underpinning power dynamics between state schools and independent schools, where despite only 7% of the UK’s school-aged population attending private fee-paying schoolsFootnote 1, almost 40% of Great British gold medal winners had been educated privately (The Guardian, 2014). Ofsted (2019) state that private school pupils dominate many sports, including rugby union, tennis, cricket, and athletics. The only sport that does not follow this trend is football, a traditionally working-class sport (Williams, 2017). Three-quarters of the equestrian team, over half the rowing contingent and 45% of hockey men and women for Team GB in the 2012 Olympics were educated privately (The Telegraph, 2014). The success of British public school pupils from the upper-middle classes has been highlighted for years across elite-level sports and at the Olympics (Tozer, 2013). British Olympic Association Chairman Lord Moynihan noted that the over-representation of private school athletes competing was not just the case in London 2012. Comparable results had also been evident four years previously at the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games, where ‘one of the worst statistics in British Sport’ occurred, as more than half of British medal winners had attended private schools (The Daily Telegraph, 2012, p.1). Similar trends remained apparent in 2016, where 32% of British medal winners at the Rio Olympics had been educated at fee-paying schools (The Guardian, 2016). By the time of the Tokyo Olympics in 2021, the proportion of British medal winners from private school backgrounds was reported to have increased to 35% (Belger, 2021). Some researchers have even suggested that such trends date back to the first Olympic Games held in Athens in 1896, where the ‘bulk’ of the team and medallists were former private school boys (Brownell, 2015). A situation that highlights how such events have been shaped by the leisure tastes of the privately educated.

Researchers have explored connections between social class and sports participation and have often critiqued inequalities surrounding such issues, particularly the extent to which someone’s social class can affect both their education and their sports participation (Morton, 2022; Bourdieu, 1984; Shilling, 1993; Riches el al., 2017). Wheeler et al. (2019) indicated that upper-middle-class children participated in a relatively high proportion of organised sports activities compared to working-class children, who, whilst participating in sporting leisure activities, find that their overall participation levels are much lower. Through this lens, Bourdieu’s (1984) work on distinction provides a fascinating insight into how the upper and middle classes use sport and leisure to differentiate and distance themselves from working-class people. Research has also highlighted that social class can affect the different sports and leisure activities individuals participate in. Wheeler et al. (2019) discovered that the upper-middle classes participated in ‘exclusive’ sports such as cricket, lacrosse, and skiing, whilst working-class children often tended to partake in ‘prole’ sports such as boxing and rugby league (Bourdieu, 1984; Wheeler, 2014).

Similarly, it has been argued that there is a clear association between social class and the private education system (Maxwell & Aggleton, 2014). There are, at times, perceptions of ‘privilege’ amongst private school pupils, which stems from social class inequalities of lower socioeconomic groups being unable to afford private education fees (Maxwell & Aggleton, 2014). According to Whigham et al. (2020), theorists highlight factors affecting people’s social class status, including income, occupation and social roles, education, available contacts and networks, moral values, and tastes. Such factors are thought to interrelate and determine socioeconomic status (Piketty, 2015; Rowthorn, 2014). Yet despite existing research indicating that social class issues impact the types of sports that people play, how often they play and with whom they participate (Wilson, 2009), there remains scope to investigate further the processes through which members of the upper-middle classes are socialised into sport. In so doing, we hope to expose the systems through which privately educated students maintain their dominance in sports and how such power dynamics are maintained through the cultural sphere of private schools (Morton, 2019).

The underpinning aim of this article is to examine and critique the leisure and sporting pastimes of male sixth-form pupils within a fee-paying private school. This article seeks to explore and better comprehend why male sixth-form pupils participate in particular sports and not others. While simultaneously seeking to understand who these students participate with and the critical underlying reasons influencing their involvement in sport. The following literature review will demonstrate the scope for research in this area, highlighting the need for a greater understanding of how the upper-middle classes – particularly those educated within a private school setting – are socialised into and through sport. Bourdieu’s (1984) theoretical insight into habitus, capital and field will be used to conceptualise the relationship between macro and micro forms of socialisation (Noble & Watkins, 2003).

2 Literature Review

2.1 Sport and Physical Activity Participation Trends

Research suggests that those in higher NS-SEC classifications are more likely to be physically active than those from lower NS-SEC categories (Sport England, 2022). For example, data suggest that in the 12 months from November 2020 to November 2021, 71.2% of those from NS-SEC Footnote 2Groups 1–2 participated in 150 min of physical activity a week in comparison to 52.3% of those from NS-SEC Groups 6–8 (Sport England, 2022). Such disparities relating to social class and relative physical activity levels have consistently been apparent within annual findings from the Active Lives Survey from November 2015 to November 2021 (Sport England, 2022). Indeed, it has long been argued that members of the lower social classes are less likely to participate in sports and physical activity and that an individual’s disposition to participate in sports stems from the complex interweaving of economic, cultural, and social influences that contribute to the development of an individual’s habitus, identity formation, and disposition towards sport and physical activity (Dagkas & Stathi, 2007; Bourdieu, 1984).

Whilst the Active Lives Survey focuses on the experiences of adults aged 16 + years, similar trends relating to social class and participation in sport/physical activity have also been evident amongst children. For example, Wheeler (2014) examined middle-class family weekends and leisure time and found that middle-class parents can better protect their weekends – unlike working-class parents – thereby ensuring that middle-class weekends can be more child-centred. Wheeler et al. (2019) noted that upper-middle-class primary-aged children partook in a mean number of 3.6 bouts of organised sports activity during a typical week compared to 0.9 mean amongst working-class children. Those children from the working class were also more reliant on the provision of sporting activities at school, as 58% of their involvement in sports activities took place within a school setting compared to only 32% of those from the upper-middle classes. Such findings suggest that upper-middle-class children engage extensively in organised sports both at school and in their leisure time, and also support previous research suggesting that those from the upper classes can involve themselves in a more diverse range of sports more frequently, than those from working-class backgrounds (Green et al., 2005; Shilling, 2017). In other words, the higher a child’s social class background, the ‘greater number, wider variety, and differing types of organised sports’ they are likely to be involved in (Wheeler et al., 2019, p.14). Roberts (2016) indicated that upper-middle-class children are likelier to have established family sporting cultures. Consequently, upper-middle-class children’s sporting lifestyles are typically set at a younger age through ‘family cultures’ and are more likely to lead to lifelong sports participation (Roberts, 2016). Bourdieu (1984) states that sports are part of an individual’s lifestyle and can also be a vital class signifier. Upper-middle-class families, in particular, actively seek to invest in their children’s social and cultural capital through sports participation (Wheeler, 2014).

An individual’s social class can affect their sports participation rates and the variety and types of sports they engage in. Something explained through the notion of ‘taste’:

For working-class families, this is a virtue made out of social necessity. Working-class lifestyles and taste follow the aesthetics of necessity, as opposed to the more refined and distanced taste of the middle class. Taste is a reflection of the class hierarchy; ideas of “good” or “bad” taste are largely determined by members of the middle class, who use their dominant class position and socioeconomic advantage, including the various forms of “capital” (social, economic, and cultural) to impress their worldview on society as a whole (Deeming, 2014, p.439).

Concerning sports, ‘taste’ can be defined as a process where individuals choose an appropriate sport for their personal preferences and lifestyle based on material constraints (Shilling, 1993). Wilson (2009) argues that sport has different class compositions and social connections. This may explain the various social class members’ tastes towards different sports. Literature indicates that the working classes often participate in ‘prole sports’ such as boxing and football, whereas higher social classes may be more likely to participate in activities such as aerobics and fitness-based leisure cultures such as yoga or pilates. Wheeler et al. (2019) further state that upper-middle-class families are more likely to participate in ‘exclusive’ sports such as rowing, horse-riding and fencing due to sporting ‘tastes’ and dispositions linked to social class. Indeed, Wilson (2009) has even suggested that the upper-middle classes actively avoid sports associated with a lower social class standing. Bourdieu (1984, p.471) explains the segregation of social class groups within sports, stating that certain sports have a ‘sense of space’ whereas other sports have outcomes ‘that’s not for the likes of us’.

Some scholars argue that Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital indicates that sports consumption is driven by knowledge, skills, preferences, and tastes, which vary significantly by social class (Wilson, 2009; Bourdieu, 1984; Hill & Lai, 2016). Consequently, people are socialised into and through sports differently depending on their social standing, but this also means that how people subsequently consume sports can further construct and reinforce class boundaries (Hill & Lai, 2016). Individuals’ disposition towards a particular sport or sports stems from their socialisation and learning of their societal position (Bourdieu, 1984). Dominant classes can and are inclined to devote considerable time and money to ‘exclusive’ sports for their children, maximising their potential and placing them higher up the social hierarchy than those who cannot access such opportunities (Bourdieu, 1984). Individuals ‘rich’ in economic capital are more likely to engage in sports that have symbolic value to their social class. The upper-middle classes can afford to participate in those sports and activities with a higher ‘cost’ in terms of time and money (Duncan et al., 2004). As a result, individuals from the higher social classes often enjoy more significant opportunities to develop their cultural, economic, and social capital and – concerning sport – are, therefore, more likely to develop a sporting habitus (Bourdieu, 1984).

2.2 Private Schools and Sport

Dagkas and Stathi (2007, p.374) believe that the most significant factors affecting sports involvement and the types of sports people access are ‘the type of school, the location of residence, proximity of facilities, financial support and significant other’. In particular, the notion of ‘significant other’ relates to primary socialisation within the family. Yet this suggests that issues of secondary socialisation linked to the type of school and schooling can also impact sports participation. The concept of doxa can describe everyday societal experiences that seem self-explanatory and taken for granted (Bourdieu, 2002). For example, the idea of doxa may encompass the role of networking within private schools with those with similar cultural and economic capital. When pupils transition into a private school, they may already have the ‘correct’ forms of capital to internalise and accept prevailing doxas within the school and, as a result, may more readily embrace doxic aspects such as a school’s underpinning sporting ethos (Grenfell, 2014). Previous research has considered the role of sports within private schools from a quantitative perspective, explaining what types of sports are undertaken but not necessarily questioning the reasons for this (Kristiansen & Houlihan, 2017; Pope & Pope, 2009). Previous literature focusing on the history of private schools has highlighted that from the nineteenth century, organised sport was used to encourage ‘athleticism’ within private schools, with sport established as a fundamental part of everyday school life (Horne et al., 2011). Implementing sport within private schools encouraged pupils to value physical prowess and competition, resulting in ‘the religion of athletics’ (Simon, 1975). Mangan (1975, p.134) argued that the emergence of athleticism within private schools allowed for charter training, enabling skill development in areas such as ‘physical and moral courage’, cooperation and loyalty, alongside the ability to ‘command and obey’. It has been argued that the development of private schools and their focus on the importance of sport allowed public school boys to develop physical forms of capital, which could later be ‘converted into economic, cultural and social capital’ (Shilling, 1993, p.56). Public school boys were therefore socialised into and through sport whilst at school, providing opportunities, facilities and drive to become sporting athletes (Swain, 2006).

In many instances, the parents of public-school boys were willing to ‘pay the price’ for their sons to gain social status through private education and fundamentally interrelated participation in sports within private school settings (Horne et al., 2011). Through the development of the ‘old boy’ network, these ‘manly men’ who emerged within/from public school settings could use their physical capital to gain social status within school settings (Connell, 2005). The emergence of elite private schools played a significant role in the development of accompanying ‘old boy’ social networks and hierarchies (Paterson, 2003; Halsey et al., 1984). Some researchers have argued that inculcating a sporting ethos and encouraging pupils to develop a sporting habitus remains prevalent within private schools (Horne et al., 2011; Kristiansen & Houlihan, 2017). However, there is minimal literature examining the role of private schools and the development of a sporting habitus amongst pupils today. The underpinning doxas and processes that contribute to the socialisation of private school pupils into and through sport therefore require further exploration, particularly given some of the issues that have previously been reported within the media and elsewhere regarding apparent trends towards the subsequent overrepresentation of former private school pupils within many elite level sports (O’Flynn, 2010; Kennedy et al., 2020; Tidén, Brun Sundblad, and Lundvall, 2021; Morton, 2022).

2.3 Habitus, Capital, Field and Doxa

Previous scholars have attempted to use Bourdieu’s (1984) theoretical ideas to bridge the gap between the macro-micro debate. Such questions often surround whether people are socialised at a macro level, with outside factors such as broader environments and the fields they are introduced to and brought up impacting socialisation aspects (Lareau, 2011). Alternatively, the micro debate holds that individual experiences and interactions with others can affect how different social classes are more inclined to a particular way of life (Noble & Watkins, 2003). Much existing research has focused primarily on the macro debate, with less focus on issues surrounding the micro debate, leaving scope for further study in such areas. There are important questions to consider on how people are socialised into specific behaviours and tastes, with a particular need to gain greater insight into the experiences and socialisation of private school pupils into sports (Morton, 2022).

On a theoretical level, habitus can be defined as an individual’s learned predispositions, tendencies, propensities or inclinations to the social world around them, which often influence their actions and/or behaviours towards activities, lifestyles and individuals which are considered ‘appropriate’ to their social standing (Tomlinson, 2004; Smith & Green, 2015). Such tendencies are learned behaviours – influenced via processes of socialisation – that often result in individuals conforming to the societal norms expected of their social class (Craig, 2016). Capital is the second part of Bourdieu’s (1984) theoretical idea, typically broken down into three subsections: economic, social, and cultural forms of capital. Economic capital is based on an individual’s financial resources. Economic resources influence the ability of people to afford different leisure activities, for example (Bourdieu, 1984). Social capital is a concept based on social connections and ‘who’ an individual maintains social networks and relationships with (Roberts & Sufi, 2009). These social interactions can include family and broader societal connections (Lareau, 2011). Finally, cultural capital is a concept of ‘what’ individuals know based on social and cultural assets, knowledge and skills often expressed through different ‘tastes’ and how their time is invested (Tomlinson, 2004). Those possessing more significant cultural capital are traditionally considered to be those from the upper-middle classes, who are typically seen as ‘well-educated’ within and across a wider range of social settings, particularly those that are often considered to be more ‘exclusive’ in terms of social standing (Bourdieu, 1984). Different social, cultural and economic capital levels result from social status, upbringing, and resources, affecting opportunities for social mobility and other aspects of social life, such as sporting dispositions and tastes (Giulianotti, 2016).

Physical capital results from an individual’s habitus and capital intertwining, producing their physical reality, appearance, and ability (Shilling, 2012). Physical capital can be a form of power and status, as it holds value within different social fields (Bourdieu, 1984). Although an individual’s physical features (physical capital) are seen as a natural process, they also result from social, cultural, and material resources (Shilling, 2004). Members of the upper classes seek to improve their physical capital through the diverse types of sports in which they participate, often focusing on activities related to health and fitness, as they view their body as a ‘project’ (Shilling, 2004). On the other hand, members of the working classes traditionally adopt a ‘make-do’ approach to their body as they have relatively little time to ‘cultivate the body’ and, instead, often place greater significance on other factors in their lives (Shilling, 2004). The upper classes maintain their dominance and distinction through physical capital to distinguish their physical appearance from more ‘common’ working-class bodies (Bourdieu, 1984, p.196).

Field is the third component of Bourdieu’s formula, ‘which involves a network or configuration of objective relations between positions’ (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992, p.97). Fields are the social spaces that people immerse themselves within. This may include areas of social life such as school, work, and sports clubs. Yet the key point is that such fields overlap, with different forms of capital valued more or less within different fields (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992). Bourdieu (1984) noted that fields are the beginning of power struggles, given that people’s forms of capital can be valued differently within and across different social ‘fields’. Therefore, the relative types or levels of capital that people possess – in conjunction with their underpinning habitus – can determine their relative standing and relative opportunities to wield and ‘control’ capital within a particular field (Benson & Neveu, 2005; Edgerton & Roberts, 2014). This leads to the conclusion of Bourdieu’s theoretical idea: that the individual’s subsequent action or behaviour may positively or negatively impact their experiences within a certain field (Bourdieu, 1984). For example, opportunities for an individual to participate in an ‘exclusive’ sport would depend upon whether they have the necessary resources – an underpinning habitus that would shape such opportunities alongside requisite forms of social, cultural, economic and physical capital – to do so (Bourdieu, 1984).

In addition to the preceding concepts integral to Bourdieu’s work, the interrelated concept of doxa is described by Bourdieu as ‘the taken for granted’ aspects of social life (Travaglia, 2018, p.867). In other words, doxa relates to the social practices within ‘fields’ that are often considered a common everyday experience that is self-explanatory and self-evident to individuals (Bourdieu, 1991, 2002). Bourdieu (2005, p.37) summarises doxa as ‘the universe of the tacit presuppositions that we accept as the natives of a certain society’. The concept of doxa has previously been used to examine the socially constructed interactions of pupils within the context of school Physical Education (PE) sessions (Hunter, 2004). Yet there remains scope to further investigate Bourdieu’s ideas of habitus, capital, and field – alongside the interrelated concept of doxa – to examine those processes that contribute to the socialisation of male sixth-form private school pupils into and through sport and, more particularly, how such processes influence an individual’s behaviours, tastes, and dispositions towards certain forms of sport and, potentially, the development of a sporting habitus.

3 Methods

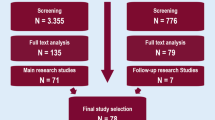

A qualitative methodology was adopted within this research project, given the underpinning aims to understand the ‘lived’, ‘felt’ and ‘undergone’ experiences of male sixth-form pupils that may have contributed to their socialisation into and through sport, their current sporting lifestyles, and whether such issues may influence the development of an underpinning sporting habitus (Bell, 2014). Qualitative research focuses not on cause and effect but on ‘rich’ in-depth meanings and explanations (Smith & McGannon, 2018). Therefore, the study was framed using an interpretivist perspective (Packard, 2017).

3.1 Sampling and the Development of a Case Study Approach

This research project was based on a case study undertaken in the sixth form of a private fee-paying school in North England. Within the school, there was a strong underpinning sporting ethos, with sport regularly played and referred to in the context of ‘games afternoon’ and sports sessions occurring every night of the week, other than Thursdays and Sundays. Strong emphasis was placed on competitive sports, with the school supporting successful sports teams, regular sporting competitions and fixtures, and having a notable roster of former alumni that had gone on to successful future professional sporting careers at elite levels.

After gaining access to the school, non-probability criterion sampling was used to select participants for the investigation (Jones, 2015). All twenty participants were male pupils from the sixth form at the school. Many were continuing their education, having previously attended the same private school for their secondary schooling, but a few pupils had joined the sixth form as direct entrants, having previously attended other private schools elsewhere in the UK and, in some cases, state schools. All participants were currently full-time boarders at the school. Likewise, all participants played sports competitively, either playing for the school and/or playing competitive sports for clubs outside of school. Subsequently, all participants had prior lived experience of the private school system, in addition to knowledge and experiences of private education, the perceived importance of sport and a sporting ethos within private schools, particularly within the chosen case study setting.

3.2 Data Collection

Data was generated through twenty semi-structured interviews ranging from thirty-seven minutes to one hour and three minutes. Implementing this interviewing method allowed for greater depth and understanding of key topic areas (King et al., 2019). Semi-structured interviews create environments for interviewees to ‘follow up on ideas, probe responses and investigate motives and feelings’ (Bell, 2014, p.162). The flexibility gained from semi-structured interviews facilitates in-depth discussions whilst also providing opportunities to probe with extended questions to generate a more detailed understanding of interviewee perceptions (Pathak & Intratat, 2016). All interviews were audio-recorded to facilitate subsequent transcription (Brinkmann & Kvale, 2018). Undertaking this process of semi-structured interviews allowed rich, in-depth data to be collected relating to the sporting experiences of participants to gain a greater understanding of socialisation in and through sport within a private school setting (Kallio et al., 2016; Mann, 2016).

3.3 Ethical Considerations

Before starting any form of data collection, ethical approval had been sought and granted for the research project. The required gatekeeper, parental, and participant consent documents were obtained for the investigation. Relevant information was provided to the gatekeeper, parents and participants about what the research would involve, their involvement, what types of topics would be discussed and what would be done with the data collected (Bell, 2014). Procedures were implemented to ensure confidentiality and anonymity by allocating pseudonyms to protect the identity of any people, places, clubs, schools, and participants mentioned within generated data (Stiles & Petrila, 2011). Participants were also allowed to ask any questions about the research being undertaken before their interviews were conducted and were also aware of their rights to withdraw from the study should they wish to do so (Dickson-Swift et al., 2009).

3.4 Data Analysis

Following the data collection process, all interviews were transcribed, which involved typing up the interviews word-for-word. While this can be time-consuming, the transcription process allows researchers to become more familiar with collected data (Bryman, 2016; Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009). Once transcripts were completed, data was analysed through a six-stage process of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Braun et al., 2019). Implementing a clear framework or thematic analysis process can help identify, understand, and describe ‘implicit’ and ‘explicit’ ideas stemming from data collected (Guest et al., 2012). Analysing data in such a way can also allow ‘rich’, detailed, and complex qualitative themes or patterns to be explored more systematically (Braun et al., 2019; Silverman, 2013). Crucially, the analysis was informed by Bourdieu’s theoretical framework. However, to move beyond Reay’s (2004) critique of the descriptive ‘overlaying’ of habitus whereby the concept is ‘assumed or appropriated rather than ‘put into practice’(p.440), we followed Wiltshire et al.’s. (2019) method that sought to use habitus as a tool for interrogating and working with data. In this way, the precise structuring powers of the habitus were not assumed a priori, but rather, the analyst’s work was to identify what those powers were and how they shaped practices concerning particular fields in the research contexts. To achieve this aim, we found it helpful to apply Jackson and Mazzei’s (2013) Deleuzian-inspired metaphor of ‘plugging in’, a term used to explain how researchers seek to connect one ‘text’ (the data) with another (e.g. habitus) to explore the knowledge that is produced. The following results and discussion section outlines key themes and patterns from this thematic analysis process. Results will be discussed in relation to four key overarching areas that impact the development of a sporting habitus amongst privately educated male sixth-form pupils: (a) the role of the family and primary socialisation; (b) the role of primary school education; (c) the impact of private secondary education; and (d) the impact of the sporting ethos within private school settings on the development of a sporting habitus. In line with ethical approval requirements, all participants’ names mentioned in the following results and discussion section are pseudonyms.

4 Results and Discussion

4.1 The Role of the Family and Primary Socialisation in the Development of a Sporting Habitus

Data collected indicated that the role of the family and processes of primary socialisation were important influences on the development of the participants’ sporting lifestyles and habitus. One recurring influencer was the role of a father figure and their involvement in sports. Parents invest time, money, and emotional energy into their children’s sporting lifestyles (Kirk & Gorely, 2000; Dorsch et al., 2009). As noted by Wheeler (2014), upper-middle-class families have the necessary forms of capital to support their children in various sports from an early age. For example, Andy explained the role that his father had played in encouraging his initial involvement in sports:

‘my dad ‘cos he’s the one that’s got me into sport, he’s the one that motivates me […] comes to every single game. […] He gets me; he got me into sport. Erm, he makes it enjoyable, […] when we train together, […] he’d get the most results […], he understands me obviously, so yeah, definitely my dad’.

Such comments emphasise the role of parents, particularly the father, in introducing their children to sports and encouraging the initial development of a sporting habitus. All participants, bar one, noted that their father introduced them to sports and that they participated in sports because of their father’s involvement. Green (2010) concurs that fathers are the most influential factor in the primary socialisation phase of introducing sports to their sons. When children are socialised into sports by their parents, the types of sports they undertake can be linked to the predispositions and tastes created and encouraged through their social class and familial influences (Bourdieu, 1984). Parents’ cultural capital influences their children’s primary socialisation and, as a result, their involvement in sports. For example, Isaac noted that:

‘I’m quite a keen golfer, and so are my dad and grandad, they are all keen golfers as well, so that’s another thing. Actually, as a family. Dad wanted me to probably do golf’… I remember being given a miniature golf set when I was five and playing with it all the time…Growing up, we had a lot of connections at the golf club. It was like an extended family.

Cultural capital, tastes, and dispositions towards certain sports stem from the social class people are attached to and, therefore, the family they grow up within. The types of sports that participants had been introduced to from an early age by their parents included cricket, rugby union, hockey, cross country, tennis, squash, golf, and skiing, further highlighting the more ‘exclusive’ sports that the upper-middle classes are traditionally introduced to and play, creating an initial sporting habitus towards certain ‘class-appropriate’ sports rather than others. Such activities are typically categorised as upper-middle class ‘exclusive’ sports due partly to the costs involved in playing such sports, with the greater economic capital available to the upper-middle classes influencing whether families can afford to play such activities (Bairner, 2007). However, the status attached to certain sports is not based purely on economic and cultural forms of capital but also on social capital. Daniel highlighted the importance of and potential to develop aspects of social capital when stating that:

‘they’re [parents] committed to it […] they’ve joined the club so give money to the club when they can, go to all the charity events, always come down to matches and support’. A lot of friends go to the club as well. It’s a place that we all feel comfortable socialising.

Parents’ and children’s involvement in sports clubs can be related to issues of social capital. Social capital can be gained through the notion of ‘whom we know’ with networking between clubs and their members, providing opportunities for developing social relationships and networks where people can choose to invest their time (Popescu et al., 2016). Parents introduce their children to the clubs that they attend and are already fully established within. This can increase both their own and their child’s social capital and can, as a result, increase opportunities to ‘network’ with others as well as increase the likelihood of them becoming involved in those ‘exclusive sports’ that are considered socially appropriate within their social class (Coalter, 2007).

Several participants noted that their involvement in sports at an early age had also been at a highly competitive level. Andy’s testimony highlighted this point poignantly:

‘I was eight years old when I dropped it [tennis], and I was ranked number one in [name of country]’ […] ‘that’s why my parents were so annoyed’ (Andy).

Upper-middle-class parents often have the inclination, cultural, social, and economic capital to support their children to participate in as much sport as possible (Wheeler, 2014). Therefore, they can encourage their children to compete at relatively high levels of sport from a young age. As such, upper-middle-class parents can influence their child’s sports participation, rates, types, and levels (Dukes, 2002). For example:

‘the past two summers, […] my parents have [sic] driven me two hours up to [name of city] every Monday and Thursday, erm, so, they have definitely put in a lot of effort, erm, they used to wake up at six in the morning to drive me to games […] they’ve done everything they can, […] encouraged me and just […] they have definitely supported me’ (Andy).

‘the main thing is buying me stuff that I need to train in. […] finding places for me to train […] I think, like where we live now in [name of country], it was kind of key that there was a gym, places to train, run […] They obviously drive me places, that was massive, […] drive to football and rugby on Saturday’s and Sunday’s’ (Connor).

Therefore, primary socialisation and the influence of families are vital in facilitating the processes through which participants were initially introduced to sport and started to develop an initial (often competitive) sporting habitus. Upper-middle-class families ‘buy into’ notions of sporting ethos and prestige and choose to invest their cultural, social, and economic capital – including significant amounts of time and effort – to provide opportunities for their children to engage in sport from an early age. Such investment can often offer an initial grounding and backdrop in sports, fundamentally underpinning future attitudes towards sports and sporting experiences (Ball, 2003).

4.2 The Role of Primary School: Continuing the Development of a Sporting Habitus?

Through their family and involvement in sports in formal club settings, the initial involvement of many upper-middle-class children in sports typically preceded their sporting experiences within any formal school setting. Within this study, there was a mixture of participants who had attended state primary schools and those who had attended private preparatory schools. Those who attended a state primary school indicated that whilst they took part in some sport at school, they had primarily participated in sports during out-of-school clubs:

‘as a child, erm, at my primary school, it was kind of like twice a week, maybe three times a week with like a club or something’…We rarely played organised sport in school, or have a games afternoon like we do here [current school] (Ben).

‘my old school it was more like 1 or 2 hours a week. So, you’d have to do it all yourself at home, out of school time’ (Daniel).

Participants who attended a private preparatory school indicated that they participated in a wider variety of sporting activities at primary school, similar to what they experienced at the current private school they attend:

‘so, at prep school, I used to go to play rugby […] hockey […] cricket […] running for all three terms’ (Isaac).

‘I think it’s basically the same [as current school] like you did games like one, one hour, forty-five, 2 hours a day. […] when I just moved to prep school, I got thrown right into it and then I’m just kind of used to it now’ (Harvey).

Such findings show a clear distinction and inequality between those educated in a primary state school and those educated in a private preparatory school, indicating the impact that operating within different fields may have on the opportunities available to individuals. Indeed, one participant stated that:

‘I’ve been in state schools and private schools everywhere’ […] ‘state schools have a lot less sport on offer compared to private schools.’ […] ‘it’s a lot like do it yourself outside of school’ (Jamie).

Those attending a private preparatory school who had families with the economic capital to achieve this could participate in a range of sports during their time at school, meaning that they continued to be socialised – through processes of secondary socialisation – into a variety of sports from a relatively young age (Nakamura et al., 2013). Those who attended a state primary school participated in fewer sports during their time at school and, therefore, continued to rely primarily on their parents to regard sports highly enough to take them to external clubs to continue their sports participation (Lenartowicz, 2016).

Whilst it has been highlighted that whether children attended a state or preparatory primary school would afford very different environments for pupils to engage in sport, data also indicated that in both the private and state sectors, participants had not fully understood at the time the reasons that they were participating in sport at primary school, expressing for example that:

‘[state school] sport was kind of something that kind of just happened before, erm, we kind of had to do it. You couldn’t really get out of it’ (Ben).

‘But like in prep school it was just kind of like you’re there cos you’re signed to do that, that kind of thing’ (Harvey).

Children’s socialisation into sport during primary school is known as the ‘sampling phase’, where they are exposed to various activities, prioritising fun and enjoyment rather than training (Kirk, 2005). This may explain why neither state primary schools nor preparatory school pupils, in the early years of their development in sport, understood the reasons why they were participating in these sporting activities, primarily taking such matters at ‘face value’ regarding the importance of sport (Jess et al., 2016).

Whilst those who attended preparatory schools were exposed to various sports that they continue to play today, such as rugby and cricket, those who were educated in state primary schools still relied heavily upon their parent’s involvement in taking them to external sports clubs, with much more limited opportunities to engage in school sport. Such points emphasise the potential impact of operating within different fields – alongside interconnected displays of cultural, economic and social capital within such fields (Widdop et al., 2016) – given the different sporting opportunities and experiences that state or preparatory school pupils encountered and, in turn, the impact that such issues potentially have upon the continued development of their sporting habitus. The predispositions of doxa also need to be considered in this respect. In other words, it is not as straightforward as suggesting that participation in particular sports and continued development of sporting attitudes and habitus is created within the prevailing ethos of private schools, given that additional factors such as parental or familial attitudes towards sport and relevant forms of capital fundamentally intertwine in the continued development of a child’s sporting habitus and practice (Stahl et al., 2018). It is, therefore, vital to consider the role of private secondary and sixth-form education on the sporting experiences of upper-middle-class pupils.

4.3 The Impact of Private Secondary and Sixth-Form Education and Continued Development of a Sporting Habitus

Within the context of a private fee-paying secondary and sixth-form school, the sporting lifestyles communicated by the pupils indicated that they took part in sports more or less daily:

‘Erm, yeah, we have games every day, we’ve got Thursday’s off, Sunday’s off’…’pretty much every other day has some form of sport. On Wednesdays, a whole afternoon is set aside for sports’ (Ben).

Many pupils do, however, also elect to take part in sports on Thursdays and Sundays, as indicated by Freddie:

‘then even on Sunday you can just go […] You can play tennis, you can play golf on a Sunday’.

Indeed, pupils participated in sports most days during term time:

‘I could do a different sport every single day if I wanted to’ (Isaac).

Additionally, the types of sports offered at the school are vast. Sports such as shooting, rugby, golf, sailing, tennis, and cricket were all mentioned as popular activities at the school. This supports the argument that the upper-middle classes have certain dispositions and tastes towards more ‘exclusive’ sports (Bourdieu, 1984; Ferry & Lund, 2018).

One of the critical reasons that pupils had initially joined the school related to the underpinning sporting reputation and ethos. Indeed, all pupils noted that their initial attraction to the school was what they had heard about sports within the school, particularly rugby:

‘I always wanted to come to the senior school here, erm, for the sport and its obviously like a very good school in all departments […] the one thing was the rugby, the culture of it, it’s pretty big, so I wanted to get in here’ (Ben).

Some pupils even stated that they knew little about the school other than the sports that were on offer:

‘I didn’t really know. I knew they were big on rugby. Erm, not a lot else’…’I knew that Rugby was what I wanted to play and that this place [the school] was the place to play it. That’s why I came’ (Daniel).

This suggests that previous knowledge of the school’s sporting legacy was often a key primary factor contributing to their decision to attend it. Cultural and social capital provided further indications as to why pupils joined the school, whether through their previous attendance at summer camps held at the school or previous family or friends who had attended the school. For example, Andy expressed that:

‘I’d been to quite a few courses, I’d come here for the summer, done some rugby courses […] I just liked the main ethos and like the atmosphere of it, so I decided to come basically’.

Such comments indicate that the school’s summer camps could provide opportunities to share aspects of the school`s sporting ethos and legacy with potential new pupils. Upper-middle-class families were already investing economic capital in developing their children’s social and cultural capital in sports-related areas before joining the school. However, running and organising such summer camps provided opportunities for prospective pupils to take aspects of their existing habitus and social and cultural capital into the ‘field’ of a private school before determining whether they wanted to join the school permanently.

Aspects of social capital – mainly networking amongst other people that participants knew who had previously attended the school themselves – were typical ways pupils heard about the school. Several participants said that they had first been introduced to the school through friends, siblings, or other family members:

‘my brother was here, and he loved it in every way so, erm, so that was obviously a big factor of why I came’ (Freddie).

‘Erm, well my uncle used to come here, so my mum kind of encouraged it’ … ‘He [uncle] is similar to me in that he loves his sport and the competition involved, so I think she [mother] knew that I would like it here’ (Harvey).

‘we got told by a friend who was here before me, who was at the same club, he said I should definitely try and come and try out for a scholarship’ (Daniel).

This illustrates the potential importance of Bourdieu’s (1984) concept of social capital, as individuals used the tools of ‘whom they knew’ within the private school field to gain cultural capital and knowledge of the school, making them distinct from pupils from the working classes. Bourdieu (1984) noted that people with similar levels of capital within the same social circles and social classes are often introduced to and exposed to fields considered ‘appropriate’ to their social standing. Such processes contribute to the continuation of differentiation and fragmentation in the practices of different social classes, separating the upper-middle classes into different fields that those from lower social classes cannot typically access (Wiltshire et al., 2019).

Such findings can likewise be linked to Bourdieu’s (1984) concept of doxa, where common-sense assumptions relating to private schools have long been shared amongst the upper and upper-middle classes, leading such groups to accept and internalise taken-for-granted notions of the role of private schools and the development of a sporting ethos. Networking amongst people with the same values and similar levels of economic, cultural and social capital leads to an acceptance amongst such groups that they can attend private school and have both the inclination and relevant forms of capital to accept the prevailing doxa within the school. In this case, the prevailing doxa can be related to the importance of sporting ethos and prestige, instilling a clear sporting habitus amongst pupils and other aspects of their studies.

4.4 Understanding the Importance of the Sporting Ethos within the Field of Private Schools

Data suggests that pupils feel enthusiastic about sports and the school they represent whilst playing sport. Sporting prestige has been instilled amongst family and friends associated with the school, creating perceived elements of distinction. Sporting lifestyles within the school have become ingrained into everyday life:

‘Well, it’s definitely, can’t call it patriotic, but they do; we say that you’d do anything for the [shirt colour], [shirt colour] being [name of school], cos we play in [colour]’ (Andy).

‘yeah, on a Wednesday, Wednesday is a big running day […] like sometimes 400, yeah even like 400 [people running]’ (Ben).

The sporting lifestyles and importance of sport are further strengthened by the concept that all school pupils get involved, not only the traditionally ‘sporty’ pupils. The importance of sport is displayed in teacher, pupil, and school attitudes, which could be argued to further develop the sporting habitus of pupils due to the cultural, social, and physical capital displayed at the school on a day-to-day basis (Bourdieu, 1984). Interhouse competitions within the school also indicate a common consensus that pupils highly regard sport over other key elements of schooling and life. The display of physical capital amongst the upper-middle classes can create a clear distinction between the upper-middle and the lower social classes (Shilling, 2017). As part of the upper-middle classes, these pupils suggested they were willing to use their physical capital and put their bodies ‘on the line’ to win a rugby inter-house competition at the school. By doing so, they used their physical capital to demonstrate their body’s ability to compete with a ‘win at all costs’ ethos (Urquiola, 2016). For example, Andy expressed:

‘Well, because you are playing your friends that are in different houses, erm, the tackles are extra, extra big you try and put in cheap shots’ […] ‘you’re just basically just out there to hurt each other it’s not about playing rugby. It’s about who can get the most injuries’.

The importance of the sporting ethos amongst its pupils was also demonstrated by placing sports participation before academia. All participants said they did or still place sport above their academic studies. This could be explained by several participants expressing that they wanted to play sports professionally. For example, Connor stated that for his future:

it depends on like’ […] ‘academics and where you go to university’ […] hopefully professional [rugby union] at some point.

This reiterates previous research on private school pupils and elite-level sporting success, where private schools are said to produce disproportionate numbers of medal winners within the Olympics and elite-level sport (Tozer, 2013). Bourdieu (1984) argued that the upper-middle classes are socialised into class ‘appropriate’ sports through primary socialisation in the family at a young age. They have the necessary ‘levels’ of capital to access private education and high-level sports clubs, thereby increasing their likelihood of being successful athletes. Private school pupils emphasise the importance of sports over their academic studies (Tozer, 2013).

The development of a sporting habitus through primary and secondary forms of socialisation has embedded amongst pupils a clear perception of the importance of sport and the life skills that pupils perceive they have gained through participation, as sport has become ingrained as part of their everyday lives (DeLuca, 2016). For example, Harvey noted:

I ‘dunno’ it’s kind of hard, like routine kind of, yeah so, it’s kind of like we have to have it now. It’s just become like, without it, I just feel a bit lazy and down’…’playing sport gives you that emphasis to stay healthy and fit.

Sport is embedded as a part of their routine lives, as pupils play sports inside their private secondary and sixth-form school as part of the curriculum with peers and outside school with family and friends during holidays. Participants noted numerous benefits to participating in sports, including social, health and physical aspects. Given the range and volumes of sports they play, physical capital is present amongst this group to help build strength and fitness. Participants provided a clear indication that they continue to play sports because they enjoy it, and they also see the physical benefits of participating in these activities, resulting in an acceptance of the positive benefits of sports becoming ingrained as part of their sporting habitus:

‘You usually sort of see it [sport] as a health benefit, don’t you’… ‘If I am playing sport regularly, I know that I am staying in shape’…’Playing sport at school keeps me active and makes me feel good about myself’ (Isaac).

‘I’m quite active, I do quite a bit of fitness’… ‘If I wasn’t playing sport I would be nowhere near as active as I am now’ … ‘So I see that [playing sport] as contributing to staying fit and healthy’ (Ben).

Participants indicated that they see benefits in their physical appearance when participating in sports, bringing to the forefront the potential benefits of investing in physical capital (Rowe, 2015). Through being immersed in a private secondary and sixth-form school, pupils continued the development of their sporting habitus and cultural capital through the curriculum offered to them, allowing them to understand better the benefits of participating in sport, knowledge which had not been evident during their time at primary school. As a result, pupils possess higher levels of cultural capital than had previously been the case (Bourdieu, 1984). Cultural capital is also displayed among pupils, as they also gained knowledge on the importance of fitness, lifestyle choices and diet towards their sports participation, which they could also apply to other aspects of their everyday lives:

‘I’m quite keen on my fitness, erm, not like party life, don’t really drink that much’ (Ben).

‘I try and pack the protein in and the carbs on’ … ‘I see what diet has done to the level of performance of others in the school, and word gets around about what to eat’ … ‘Protein is the big one, everybody is talking about the need to eat as much [protein] as possible’ (Andy).

Exploring the sporting lifestyles of these pupils through the family and processes of primary socialisation, to the influence of primary school and the role of private secondary and sixth-form education can help to highlight that an individual’s sporting habitus is not a straightforward process created early in childhood and then remaining static (Holt, 2008). Instead, by engaging with Bourdieu’s (1984) concepts of habitus, capital, field and doxa, it becomes apparent that a sporting habitus may be introduced from a relatively young age through processes of primary socialisation and then continue to further develop through involvement and interaction of different forms of capital within the various social fields that an individual is involved.

5 Conclusion

This research project used semi-structured interviews to gain in-depth perspectives on male pupils’ sporting habitus and lifestyles in a private sixth-form school in the UK. Applying Bourdieu’s (1984) theoretical ideas has helped to develop a sociological explanation and critique of the processes through which private school pupils are socialised into sports. As previous literature indicates, the sporting lifestyles of male pupils studying in the sixth form of a private fee-paying school involve displays of relatively high volumes of social and cultural capital, which are evident, in particular, in the types of ‘exclusive’ sports they play such as golf, skiing, rugby union, and horse-riding both inside and outside school (Warde, 2006). Sports like these indicate elevated economic, social, and cultural capital levels. Such sports are often considered socially ‘appropriate’ to the tastes and dispositions of the upper-middle classes (Warde et al., 2009). However, pupils also emphasise the importance of physical capital and how their involvement in such sports can provide a physical ‘edge’ to perform at elite levels. Members of the upper-middle classes often view their body as a ‘lifelong process’ to develop and improve their physical appearance and achieve a ‘distinct’ physical capital that distinguishes them from the lower classes. Such trends are evident, in part, in how often pupils participate in sport during their time at school, with most pupils engaging in sport 5–7 days a week. This rate of participation is also reflected in their home life, where pupils continue to participate in sports with their families, with other researchers suggesting that the upper-middle classes can even feel guilty when they do not play sports (Kristiansen & Houlihan, 2017). Pupils’ attitudes towards sport stem from their established sporting habitus. Given primary and secondary socialisation processes, upper-middle-class private school pupils are enthusiastic about leading active lifestyles.

The processes influencing the development of a sporting habitus within pupils in a private school are not as clear-cut and concise as previous literature has perhaps suggested (Holt, 2008). An individual`s sporting habitus, tastes, and dispositions towards sports and whom they participate with are the result of interrelating factors of primary socialisation, the family, and the different social fields to which they are exposed, whether this be the school they attend, the clubs they join, or any other social setting involving sport. Although an individual`s sporting habitus stems from their primary socialisation phase, the concept of habitus does not remain fixed throughout their lives. As individuals move within and between different fields within society, further developments in their sporting habitus occur. Individuals within this case study have typically experienced primary socialisation as part of the upper-middle-class networks within which they operate. As such, they share similar values and goals alongside cultural, social, economic, and physical capital. Attending a private school that regards sport highly and integrates sport and a strong sporting ethos into pupils’ lives emphasises the impact different fields can have on developing a sporting habitus (Bourdieu, 1984). Depending upon whether they had previously attended a state primary school or private preparatory school, not all pupils had experienced a robust sporting underpinning within school at primary school age, for example. Within the context of a private fee-paying secondary and sixth-form school, aspects of doxa surrounding common-sense assumptions on the role of private schools and the development of a sporting habitus hold some validity. However, private schooling alone has not developed a strong sporting habitus among pupils. It has instead provided pupils with the opportunity to fulfil their individual sporting tastes, interests and habitus, which started to become ingrained as an aspect of primary socialisation from a relatively early age.

Bourdieu’s (1984) theoretical ideas have provided a valuable interpretation of how individuals are socialised into and through sport. More particularly, it is evident that Bourdieu’s (1984) work needs to be considered in greater depth to critically examine how the upper-middle classes are socialised into sport. The qualitative approach adopted within this investigation has provided an opportunity to investigate micro elements of how a sporting habitus is developed amongst individuals – an aspect that has not always been explored thoroughly in the existing literature – whilst ensuring that broader social issues that influence macro-level debates are also considered. In this manner, Bourdieu’s (1984) ideas regarding habitus, capital and field help explain how the distinct levels of capital one possesses can influence how private school pupils are socialised into and through sports and develop a sporting habitus within different social fields. In so doing, the research provides a greater understanding of how class influences sports participation and the processes through which private schools maintain their dominant position when producing athletes who then go on to sporting and Olympic success.

Notes

Private schools (also known as ‘independent schools’) charge fees to attend instead of being funded by the government. Pupils do not have to follow the national curriculum. All private schools must be registered with the government and are inspected regularly.

The NS-SEC is a nested classification. It has 14 operational categories, with some sub-categories, and is commonly used in eight-class, five-class, and three-class versions. Only the three-category version is intended to represent any form of hierarchy. The version intended for most users (the analytic version) has eight classes: 1.Higher managerial and professional occupations; 2.Lower managerial and professional occupations; 3.Intermediate occupations (clerical, sales, service) 4.Small employers and own account workers 5.Lower supervisory and technical occupations 6.Semi-routine occupations 7.Routine occupations 8.Never worked or long-term unemployed.

References

Bairner, A. (2007). Back to basics: Class, social theory, and sport. Sociology of Sport Journal, 24(1), 20–36.

Ball, S. J. (2003). Class strategies and the education market: The middle classes and social advantage. Routledge.

Belger, T. (2021). Private schools extend Olympic medal lead but Eton stumbles [Internet]. Available from https://schoolsweek.co.uk/where-team-gb-athletes-school-medals-state-private/ [Accessed 11 January 2023].

Bell, J. (2014). Doing your Research Project: A guide for first-time researchers in education, health, and social science (5th ed.). Open University Press.

Benson, R., & Neveu, E. (2005). Bourdieu and the journalistic field. Cambridge.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A Social Critique of the judgement of taste. Routledge.

Bourdieu, P. (1991). Sport and social class. Rethinking popular culture: Contemporary perspectives in cultural studies. University of California.

Bourdieu, P. (2002). Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (2005). The political field, the social science field, and the journalistic field. In R. Benson, & E. Neveu (Eds.), Bourdieu and the Journalistic Field (pp. 29–47). Cambridge.

Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. (1992). An invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Cambridge, Polity Press.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–102.

Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., & Terry, G. (2019). Thematic analysis. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences (pp. 843–860). Singapore, Springer.

Brinkmann, S., & Kvale, S. (2018). Doing interviews. Sage.

Brownell, S. (2015). Sport since 1750. In J. R. McNeill, & K. Pomeranz (Eds.), The Cambridge World History: Volume VII (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Bryman, A. (2016). Social Research Methods (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Coalter, F. (2007). Sports clubs, social capital, and social regeneration: ‘ill-defined interventions with hard to follow outcomes’? Sport in Society, 10(4), 537–559.

Connell, R. (2005). Growing up masculine: Rethinking the significance of adolescence in the making of masculinities. Irish Journal of Sociology, 14(2), 11–28.

Craig, P. (2016). Sport sociology (3rd ed.). Sage.

Dagkas, S., & Stathi, A. (2007). Exploring social and environmental factors affecting adolescents’ participation in physical activity. European Physical Education Review, 13(3), 369–384.

Deeming, C. (2014). The choice of the necessary: Class, tastes and lifestyles: A bourdieusian analysis in contemporary Britain. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 34(7/8), 438–454.

DeLuca, J. (2016). Like a fish in water’: Swim club membership and the construction of the upper-middle-class family habitus. Leisure Studies, 35(3), 259–277.

Dickson-Swift, V., James, E. L., Kippen, S., & Liamputtong, P. (2009). Researching sensitive topics: Qualitative research as emotion work. Qualitative Research, 9(1), 61–79.

Dorsch, T., Smith, A., & McDonough, M. (2009). Parents’ perceptions of child-to-parent socialisation in organised youth sport. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 31(4), 444–468.

Dukes, R. (2002). Parental commitment to competitive swimming. Free Inquiry in Creative Sociology, 30(2), 185–198.

Duncan, J., Al-Nakeeb, Y., Nevill, A., & Jones, M. (2004). Body image and physical activity in British secondary School Children. European Physical Education Review, 10(3), 243–260.

Edgerton, J. D., & Roberts, L. W. (2014). Cultural capital or habitus? Bourdieu and beyond in the explanation of enduring educational inequality. Theory and Research in Education, 12(2), 193–220.

Ferry, M., & Lund, S. (2018). Pupils in upper secondary school sports: Choices based on what? Sport Education and Society, 23(3), 270–282.

Giulianotti, R. (2016). Sport: A critical sociology (2nd ed.). Cambridge.

Green, K. (2010). Key themes in Youth Sport. Routledge.

Green, K., Smith, A., & Roberts, K. (2005). Social Class, Young people, Sport, and Physical Education. In K. Green, & K. Hardman (Eds.), Physical Education: Essential issues (pp. 180–196). SAGE.

Grenfell, M. J. (2014). Pierre Bourdieu: Key concepts. Routledge.

Guest, G., MacQueen, M., & Namey, E. (2012). Applied Thematic Analysis. SAGE.

Halsey, A., Heath, A., & Ridge, J. (1984). The political arithmetic of public schools. British Public Schools: Policy and Practice, 17(4), 9–44.

Hill, B., & Lai, A. (2016). Class talk: Habitus and class in parental narratives of school choice. Journal of Marketing Management, 32(13–14), 1284–1307.

Holt, L. (2008). Embodied social capital and geographic perspectives: Performing the habitus. Progress in Human Geography, 32(2), 227–246.

Horne, J., Lingard, B., Weiner, G., & Forbes, J. (2011). Capitalising on sport’: Sport, physical education, and multiple capitals in Scottish Independent schools. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 32(6), 861–879.

Hunter, L. (2004). Bourdieu and the social space of the PE class: Reproduction of Doxa through practice. Sport Education and Society, 9(2), 175–192.

Jackson, A., & Mazzei, L. (2013). Plugging one text into another: Thinking with theory in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 19(4), 261–271.

Jess, M., Keay, J., & Carse, N. (2016). Primary physical education: A complex learning journey for children and teachers. Sport Education and Society, 21(7), 1018–1035.

Jones, I. (2015). Research methods for Sport studies (3rd ed.). Abingdon, Routledge.

Kallio, H., Pietilä, A. M., Johnson, M., & Kangasniemi, M. (2016). Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(12), 2954–2965.

Kennedy, M., MacPhail, A., & Power, M. (2020). The intersection of ethos and opportunity: An ethnography exploring the role of the ‘physical curriculum’ in cultivating physical capital in the elite educated student. Sport Education and Society, 25(9), 990–1001.

King, N., Horrocks, C., & Brooks, J. (2019). Interviews in qualitative research (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Kirk, D. (2005). Physical education, youth sport and lifelong participation: The importance of early learning experiences. European Physical Education Review, 11(3), 239–255.

Kirk, D., & Gorely, T. (2000). Challenging thinking about the relationship between school physical education and sport performance. European Physical Education Review, 6(2), 119–134.

Kristiansen, E., & Houlihan, B. (2017). Developing young athletes: The role of private sport schools in the Norwegian sport system. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 52(4), 447–469.

Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2009). Interviews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Lareau, A. (2011). Unequal childhoods: Class, race and Family Life. California, University of California Press.

Lenartowicz, M. (2016). Family leisure consumption and youth sport socialisation in post-communist Poland: A perspective based on Bourdieu’s class theory. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 51(2), 219–237.

Mangan, J. (1975). Athleticism: A case study of the evolution of an educational ideology. In B. Simon, & L. Bradley (Eds.), The victorian public school: Studies in the development of an educational institution. Dublin, Gill and Macmillan.

Mann, S. (2016). The research interview: Reflective practice and reflexivity in research processes. Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Maxwell, C., & Aggleton, P. (2014). The reproduction of privilege: Young women, the family and private education. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 24(2), 189–209.

Morton, A. (2019). Physical education and sport in Independent schools: A sociological perspective (Thesis.). Loughborough University.

Morton, A. (2022). One of the worst statistics in British sport’: A sociological perspective on the over-representation of independently (privately) educated athletes in Team GB. Sport Education and Society, 27(4), 393–406.

Nakamura, P., Teixeira, I., Papini, C., Lemos, N., Nazario, M., & Kokubun, E. (2013). Physical education in schools, sport activity and total physical activity in adolescents. Revista Brasileira De Cineantropometria & Desempenho Humano, 15(5), 517–526.

Noble, G., & Watkins, M. (2003). So, how did Bourdieu learn to play tennis? Habitus consciousness and habituation. Cultural Studies, 17, 530–538.

O’Flynn, G. (2010). The business of ‘bettering’ students’ lives: Physical and health education and the production of social class subjectivities. Sport Education and Society, 15(4), 431–445.

Ofsted (2019). Inspecting independent schools: pre-registration and material change inspections. [Internet] Available from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/inspecting-independent-schools-pre-registration-and-material-change-inspections [Accessed on 1st March 2019].

Packard, M. (2017). Where did interpretivism go in the theory of entrepreneurship? Journal of Business Venturing, 32(5), 536–549.

Paterson, L. (2003). Scottish education in the twentieth century. Edinburgh University Press.

Pathak, A., & Intratat, C. (2016). Use of semi-structured interviews to investigate teacher perceptions of student collaboration. Malaysian Journal of ELT Research, 8(1), 1–10.

Piketty, T. (2015). About capital in the twenty-first century. American Economic Review, 105(5), 48–53.

Pope, D., & Pope, J. (2009). The impact of college sports success on the quantity and quality of student applications. Southern Economic Journal, 75(3), 750–780.

Popescu, G., Comanescu, M., & Sabie, O. (2016). The role of human capital in the knowledge-networked economy. Psychosociological Issues in Human Resource Management, 4(1), 168–174.

Reay, D. (2004). It’s all becoming a bit habitus’: Beyond the habitual use of habitus in educational research. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 25(4), 431–444.

Riches, G., Rankin-Wright, A., Swain, S., & Kuppan, V. (2017). Moving forward: Critical reflections of doing Social Justice research. In J. Long, T. Fletcher, & B. Watson (Eds.), Sport, leisure and Social Justice (pp. 209–221). Routledge.

Roberts, K. (2016). Youth leisure as the context of youth sport. In K. Green, & A. Smith (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Youth Sport (pp. 18–25). Routledge.

Roberts, M., & Sufi, A. (2009). Control rights and capital structure: An empirical investigation. The Journal of Finance, 64(4), 1657–1695.

Rowe, N. (2015). Sporting capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis of sport participation determinants and its application to sports development policy and practice. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 7(1), 43–61.

Rowthorn, R. (2014). A note on Piketty’s capital in the twenty-First Century. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 38(5), 1275–1284.

Shilling, C. (1993). The body and Social Theory. Sage.

Shilling, C. (2004). Physical capital and situated action: A new direction for corporeal sociology. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 25(4), 473–487.

Shilling, C. (2012). The body and Social Theory (3rd ed.). Sage.

Shilling, C. (2017). The body, class and social inequalities. In J. Evans (Ed.), Equality, education, and physical education (pp. 55–73). Routledge.

Silverman, D. (2013). Doing qualitative research: A practical handbook. SAGE.

Simon, B. (1975). The victorian Public School: Studies in the development of an Educational Inst.; a Symposium based on papers delivered at a conference on the Victorian Public School Held at Digby Hall. Leicester.

Smith, A., & Green, K. (2015). Routledge Handbook of Youth Sport. Routledge.

Smith, B., & McGannon, K. R. (2018). Developing rigor in qualitative research: Problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 101–121.

Sport England (2022). Active Lives Adult Survey: November 2020-21 Report [Internet]. Available from: https://sportengland-production-files.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2022-04/Active%20Lives%20Adult%20Survey%20November%202021%20Report.pdf?VersionId=nPU_v3jFjwG8o_xnv62FcKOdEiVmRWCb [Accessed 16 February 2022].

Stahl, G., Wallace, D., Burke, C., & Threadgold, S. (2018). International perspectives on Theorizing aspirations: Applying Bourdieu’s tools. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Stiles, P., & Petrila, J. (2011). Research and confidentiality legal issues and risk management strategies. Psychology Public Policy and Law, 17(3), 333–356.

Swain, J. (2006). The role of sport in the construction of masculinities in an English Independent junior school. Sport Education and Society, 11(4), 317–335.

The Telegraph (2014). Ofsted: state school pupils ‘under-represented’ in top sport. [Internet] Available from: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/education/educationnews/10912704/Ofsted-state-school-pupils-under-represented-in-top-sport.html [Accessed 15th January 2019].

The Daily Telegraph (2012). London 2012 Olympics: David Cameron says too many top British athletes went to public school [Internet] Available from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/politics/9378405/David-Cameron-says-too-many-top-British-athletes-went-to-public-school.html [Accessed 15th February].

The Guardian (2014). Level playing field? Private school pupils still have head start in sports. [Internet] Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2014/jun/20/ofsted-state-schools-must-improve-sports-students [Accessed on 8th January 2019].

The Guardian (2016). Third of Britain’s Rio medallists went to private schools. [Internet] Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2016/aug/22/third-britain-medallists-rio-olympics-private-schools-sutton-trust [Accessed 11 January 2023].

Tidén, A., Sundblad, B., G and, & Lundvall, S. (2021). Assessed movement competence through the lens of Bourdieu – a longitudinal study of a developed taste for sport, PE and physical activity. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 26(3), 255–267.

Tomlinson, A. (2004). Pierre Bourdieu and the sociological study of Sport: Habitus, capital and field. In R. Giulianotti (Ed.), Sport and Modern Social theorists. Palgrave Macmillan.

Tozer, M. (2013). One of the worst statistics in British Sport, and wholly unacceptable’: The contribution of privately educated members of Team GB to the summer Olympic games, 2000–2012. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 30(12), 1436–1454.

Travaglia, J. (2018). Disturbing the Doxa of Patient Safety: Comment on false dawns and New Horizons in Patient Safety Research and Practice. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 7(9), 867–869.

Urquiola, M. (2016). Competition among schools: Traditional public and private schools. In E. A. Hanushek, S. Machin, & L. Woessmann (Eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Education (pp. 209–237). Elsevier.

Warde, A. (2006). Cultural capital and the place of sport. Cultural Trends, 15(2–3), 107–122.

Warde, A., Silva, E., Bennett, T., Savage, M., Gayo-Cal, M., & Wright, D. (2009). Culture, class, distinction. Routledge.

Wheeler, S. (2014). Organised activities, educational activities, and family activities: How do they feature in the Middle-Class family’s weekend? Leisure Activities, 33(2), 215–232.

Wheeler, S., Green, K., & Thurston, M. (2019). Social class and the emergent organised sporting habitus of primary- aged children. European Physical Education Review, 25(1), 1–20.

Whigham, S., Hobson, M., Batten, J., J. and, & White, A. (2020). Reproduction in physical education, society and culture: The physical education curriculum and stratification of social class in England. Sport Education and Society, 25(5), 493–506.

Widdop, P., Cutts, D., & Jarvie, G. (2016). Omnivorousness in Sport: The importance of social capital and networks. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 51(5), 596–616.

Williams, J. (2017). Games without frontiers: Football, identity, and modernity. Routledge.

Wilson, T. (2009). The Paradox of Social Class and sports involvement: The role of Cultural and Economic Capital. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 37(5), 5–16.

Wiltshire, G., Lee, J., & Williams, O. (2019). Understanding the reproduction of health inequalities: Physical activity, social class, and Bourdieu’s habitus. Sport Education and Society, 24(3), 226–240.

Author information