Abstract

Recreationists differ in their engagement, specialization and involvement in their leisure activity. Recreation specialization can be seen as a continuum from the novice to the highly advanced (or as a career process), sometimes grouped into three or four categories. Within the highest category of advanced recreationists, a specific hard-core, elite or devotee segment was identified. In this study, the highly specialized or elite segment of birdwatchers was addressed. Therefore, members of the Club 300 (in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland), were studied in comparison to non-members. Members of the Club 300 are required to have observed about 300 bird species in their respective country. Scales on recreation specialization, motivations and involvement were applied. A general linear multivariate model revealed a significant influence of Club 300 membership on the total set of the different dimensions with an eta-squared of 0.315, representing a high effect size. Subsequent uni-variate analyses showed that members differed from non-members significantly in all dimensions. Thus, Club 300 members fulfil the requirements of an elite segment because they differ in knowledge and behavior, as well as in their motivations from other birdwatchers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

People differ in their involvement, engagement and motivation for their leisure or recreational activities. Some researchers analyzed this engagement and involvement and found differences among individuals (heterogeneity), sometimes conceptualized as serious leisure, recreation specialization or involvement (Bryan, 1977; Kyle et al., 2007; Stebbins, 1992). In short, Bryan (1977) suggested a career of specialization in leisure, from the beginner to the specialized, which is in some, but not all aspects congruent to Stebbin’s (1992) theory of serious leisure, with project-based, casual and serious participants (see below). Kyle et al. (2007), however, had a stronger emphasize on the psychological concept of involvement into a leisure activity.

A special case of recreation specialization and of serious leisure are the elite or “hard core” participants (Scott & McMahan, 2017; in the following the term elite is used). These participants show a high involvement, combined with a high knowledge and high skills that places them at the extreme end within the cluster or group of the highly specialized recreationists. This study seeks to shed light on the elite recreationists by comparing them with less specialized birders. Therefore, members of a defined elite group (Club 300) were analyzed, based on previous concepts of recreational specialization and motivations for birding.

Birdwatchers from Germany, Austria and Switzerland were studied. These birders were members of the three respective Clubs 300, a special organization of birders in all three countries who have seen and identified more than 300 different bird species in their specific country. Thus, there is a Club 300 in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland. Having seen at least 300 species in each of these countries is a high threshold that requires a lot of field activity, usually high knowledge, and some regional or countrywide travel. This represents an extreme grade of recreation specialization. The data are compared with birdwatchers that are non-members. Questionnaires were based on previous work studying recreation specialization, motivations, and involvement. Most studies in birding were based on the recreation specialization concept (Bryan, 1977; e.g., Lee & Scott, 2004) and on motivational constructs (e.g., Randler, 2023). These well-established measures are used to compare both groups, and in combination with demographic factors to predict the membership in the Club 300 and, thus, differentiate between elite and less specialized birders.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Recreation Specialization and the Elite Concept of Leisure

Leisure research about specialized groups is often embedded in the construct of the social world (Stebbins, 2017). Every group is based on some kind of ‘ethos’, which is the spirit of the respective leisure community forming the social world of the participants (Stebbins, 2016). This social world is the organizational milieu or framework where the associated ethos is expressed (for example as an attitude or a value) and realized (as a practice; Stebbins, 2016, 2017). These beliefs and values hold the group together and are usually coherent. Although the social world is an “amorphous entity” (Stebbins, 2016, p. 155) it enables a general framework for studying leisure.

Within this framework, different conceptual approaches are used to depict diversity in the engagement and involvement in a leisure activity. Stebbins (2020) defined three types of leisure categories: the project-type of leisure, casual leisure, and serious leisure. Project-based leisure refers to a given project, and when it is over, participants leave. Casual leisure is related to a leisure activity that might be carried out regularly and over a longer time, but only irregular or seldom. Serious leisure involves a strong commitment and engagement in a leisure activity (Stebbins, 1992, 2017). Thus, the elite participants are included in the serious leisure segment. Similarly, most studies based on the recreation specialization concept identify three groups: novice, intermediate and advanced birders (Randler, 2021a). In addition to grouping, the concept of a continuum from a novice to an advanced/skilled participant is found in the serious leisure literature (Stebbins, 1982) as well as in the recreational specialization literature (Bryan, 1977). Both approaches also view their concept as a development from one career stage to another (Bryan, 1977; Stebbins, 1982). This means that recreation specialization can be seen as a continuum in behavior between the generalists with low involvement and the specialists with a high involvement (Bryan, 1977, 2000). The concept is based on four factors: first, the investment in leisure activities (time, money, effort), second, knowledge about and skill in this activity, third, the activity itself, and fourth, the degree of specialization (Bryan, 1977). This conceptualization was refined by Scott and Shafer (2001) into a three-dimensional construct including a behavioral, a cognitive and an affective component (Lee & Scott, 2004).

In the following, Lee and Scott (2004) developed a measurement model of birding recreation specialization to portray the different dimensions of the construct. The behavioral component is indicated by equipment, previous participation, and experience. The cognitive dimension includes the level of knowledge and skill about and competence in the activity. The affective component includes attachment and engagement which is based on the centrality to lifestyle and continued participation (Randler, 2021a). Thus, the birding specialization construct based on the measurement of Lee and Scott (2004) has been chosen as a basis for this current research study because the questions and items are very specifically developed for birding activities.

Although the measurement of birding specialization is parametric and continuous, researchers sometimes classified birders into categories. For example, McFarlane (1994) grouped birdwatchers into four categories: casual, novice, intermediate and advanced birders. Hvenegaard (2002) categorized birders into three groups: advanced-experienced (10%), advanced-active (50%), and novices (40%). Scott and Thigpen (2003), again, identified four groups: casual birders, interested birders, active birders, and skilled birders. Subsequently, Scott et al.’s (2005) classification was refined into three categories: namely: committed, active and casual birdwatchers. This classification was confirmed in eBird participants by Harshaw et al. (2020) and Lessard et al. (2018). Although Lessard et al. (2018) reported only two clusters, this was owed to the exclusion of novice birdwatchers (because novice birders usually do not use eBird), which formed a separate group in all other studies. Thus, for North America, a three-group solution of birders can be assumed. This three-group classification was further supported by a European study focusing on German birdwatchers (Randler, 2021a).

2.2 Elite Leisure Participation

In a further attempt, within the cluster of highly specialized birders a group of elite birdwatchers has been defined (Scott & McMahan, 2017). These participants form a group that involves extraordinary commitment (Scott & McMahan, 2017). This classification is based on the general measurement construct of Lee and Scott (2004) and elite birders are from the advanced segment, when following the recreation specialization concept of Scott and Shafer (2001). Following Stebbin’s theory, elite birders are a part of the serious leisure participants. Thus, the high end of the career stages is defined by Stebbins (1992) as devotees or as ‘hard core’ participants by Scott and McMahan (2017). Therefore, the elite concept receives support from both theoretical constructs. Although Stebbin’s theory (2020) is widely used in leisure research, the recreation specialization concept is more developed in birding studies, with items and questions especially adapted to this activity, thus more specific questions, e.g., by asking for the number of bird species someone can identify, or the number of birding trips. This high recreation specialization further influences other aspects of life, such as travel intentions (Callaghan et al., 2018; de Salvo et al., 2020).

Other studies in the elite segment are rare. For example, Siegenthaler and O'Dell (2003), using the serious leisure conceptualization, further developed the aspect of ‘core devotees’ to refine the categories. Concerning golfers, participants in this leisure activity enjoyed the challenge, but not for competition, rather for personal enrichment (Siegenthaler and O'Dell, 2003). In contrast, Brown (2007) emphasized the competition aspect as a strong factor in serious shag dancers. Thus, competition may also play a role in Club 300 members. Further studies suggested that in elite leisure participants and core devotees, identity, social relatedness and centrality to lifestyle play a central role in their leisure (Brown, 2007).

2.3 Birding as Leisure Activity

Birding is the most important activity of wildlife watchers, with an average rate of 16 days per year watching birds away from home (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2018). In comparison to game or duck hunting and fishing/angling, birding is a nature-related outdoor activity, but with a non-consumptive component, which separates it clearly from the consumptive dimensions, especially when considering animal welfare attitudes (Randler et al., 2021). Birding has been an emerging leisure activity also outside the USA (e.g., China: Ma et al., 2013; Brazil: de Camargo Barbosa et al., 2021). In common with fishing and hunting, birding also has a “care”-component when birdwatchers invest money and effort for bird feeding or for erecting nest boxes (Dayer et al., 2019). A special aspect of birding is the participation in many different citizen science projects, such as feeder watching, breeding bird censuses, or submitting data to web-based platforms (Randler, 2021b; Sullivan et al., 2014).

Different subpopulations of birders have already been studies (Eubanks et al., 2004), but the elite devotees have been rarely addressed. Scott et al. (1999) studied the First Annual Great Texas Birding Classic, an event which involved three full days of birdwatching along the Texas coast. This event, by its program, attracts elite birders. This has been corroborated by the number of bird species on their life list: 72% of the participants maintained a life-list and reported an average of 1,139 species (Scott et al., 1999). This is in line with a study on twitching, which concerns people that travel long distances to see specialties and rare bird species within a given geographic area (Booth et al., 2011). However, such specialized birders have not been studied with respect of their membership in an organization (in the case of this current study, the Club 300). Nevertheless, it is obvious, that elite birdwatchers also have their special formal organization to pursue their hobby. Other birdwatching or nature conservation organization, however, have already been in focus of research. For example, Cole and Scott (1999) compared members of the American Birding Association (ABA) with holders of a conservation passport (which allows free entrance in conservation areas). The ABA members scored higher in all dimensions of recreation specialization: higher skill/knowledge level, higher financial expenditures, more days outdoors, and more field trip outings.

Another field of research is addressed by travelling and travel intentions (Butler, 2019; Goodfellow, 2013, 2015). Usually, travel to foreign countries or remote areas is often a characteristic of highly specialized birders (Callaghan et al., 2018; de Salvo et al., 2021) However, concerning travel, the limiting factor may be time and money, so there can be highly specialized birders that do not travel because they are on a budget, and thus, roam only their own country or federal state.

2.4 The Current Study

Previous studies showed a considerable effort in segmenting and describing birdwatchers. However, previous approaches did not assess the membership in different organizations related to recreation specialization, and especially not the membership in an elite segment. To address the aspect of elite recreation specialization, members of the Club 300 were compared with non-members. The constructs of recreation specialization and motivations have been chosen because previous work exists on the refinement of the scales for measurement. In this study, the recreational specialization concept containing the three dimensions skill/knowledge, behaviour and commitment have been applied (e.g., Scott & Shafer, 2001), as well as the involvement construct (Kyle et al., 2007) and birding motivations (McFarlane, 1994; Randler, 2022).

3 Materials and Methods

3.1 Sample

Data for this study were collected via the Online Research Tool SoSciSurvey during 2020. After explaining the study, respondents who agreed to participate clicked on a button (“yes”) as a formal consent. Participants were able to stop and leave at any time without any consequences. Recruitment was done by a broad distribution of the survey link to gather data from a variety of birdwatchers, from garden bird feeder watchers to the highly skilled specialized members of the Club 300. On the forum website of all three clubs (Austria, Germany, Switzerland), an advertisement was placed, and people were encouraged to participate. Further, all large bird and nature-related organizations were contacted to distribute the link. From the federal states or regional chapters of scientific ornithological unions, societies and clubs, all member organizations gathered within the DDA (Dachverband Deutscher Avifaunisten; an umbrella organization) were asked for participation by using postings on their websites or by distribution of the link on their mailing lists. To address further participants, an advertisement was published in a printed birdwatching journal (“Vögel”; which is “birds” in German). The number of participants per federal state in Germany was highly positively correlated with the number of inhabitants of the federal state (r ≈ 0.9). The study was granted permission by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Economics and Social Sciences of the Eberhard Karls University Tübingen.

3.2 Measurements

3.2.1 Demographics

Demographic data were age (in years), gender (male, female, diverse) and highest formal qualification.

3.2.2 Birding Specialization, Involvement, and Motivations

Birding specialization, involvement, and motivations were measured with an array of previously published instruments (see below). Birding specialization includes the dimensions skill/knowledge, behaviour and psychological commitment, which is separated into behavioral commitment and personal commitment (Lee & Scott, 2004).

3.2.3 Skill and Knowledge

Skill and knowledge included open-ended questions about the number of species to be able to identify without a field guide by appearance (e.g., from Cheung et al., 2017; Lee & Scott, 2004; Lessard et al., 2018), and by song (Lee & Scott, 2004; Lessard et al., 2018), an self-assessment of knowledge ranging from 1 (novice) to 5 (expert; Lee & Scott, 2004), originally on a seven-point Likert scale but transformed to a five-point Likert scale. The open-ended questions were z-transformed prior to analysis. This was done because the range was from 0 up to 1,000 different species. However, the open-ended questions allowed a comparison of Club 300 members and non-members in more detail. Cronbach’s α of the skill/knowledge scale was 0.85.

3.2.4 Behavior

This behavior scale refers to self-reported real behavior. This scale contained the number of birding trips taken last year (at least 2 km away from home; McFarlane and Boxall, 1996), number of days spent in birding during the last year (Cheung et al., 2017; Costa et al., 2018; Hvenegaard, 2002), the total number of bird species on the lifelist (Tsaur & Liang, 2008), the number of bird books owned (McFarlane, 1994), replacement value of the total equipment in € (Cheung et al., 2017; Hvenegaard, 2002; Tsaur & Liang, 2008) and the number of species on a national list, concerning Germany, Austria and Switzerland (developed for this study). All these questions were open ended to allow a comparison but were z-transformed prior to analysis. Cronbach’s α of the behavior scale was 0.80.

3.2.5 Personal Commitment

Personal commitment was measured with three questions: “Other leisure activities don’t interest me as much as birding.” (Lee & Scott, 2004); “I would rather go birding than do most anything else.” (Lee & Scott, 2013); and “Others would probably say that I spend too much time birding.” (Lee & Scott, 2013). All items were measured on a five-point Likert scale. Cronbach’s α of the personal commitment scale was 0.76.

3.2.6 Behavioral Commitment

This scale refers to behavioral commitment. Three items were used on a five-point Likert scale. “If I couldn’t go birding, I am not sure what I would do.” (Lee & Scott, 2004); “If I stopped birding, I would probably lose touch with a lot of my friends.” (Lee & Scott, 2013); “Because of birding, I don’t have time to spend participating in other leisure activities.” (Lee & Scott, 2013). Cronbach’s α of the behavioral commitment scale was 0.73.

3.2.7 Involvement

Involvement was assessed with the modified involvement scale (Kyle et al., 2007). Three items each measured “attraction” (Cronbach’s α = 0.86), “centrality to lifestyle” (Cronbach’s α = 0.86), and “social bonding” (Cronbach’s α = 0.79). Identity was measured with one item (see Lessard et al., 2018).

3.2.8 Motivations

The assessment of motivations was based on the three-factor model of outdoor recreation motivations (Decker et al., 1987; confirmed by Randler, 2022). The first dimension considers social motivation, based on items such as “gain respect from other birders” or “meet people who share my interests” (Cronbach’s α = 0.84). The second dimension is achievement, measured with items like “seeing as many birds as possible” or “seeing birds not seen before” (Cronbach’s α = 0.83). Third, “enjoying being alone” and “experiencing nature” were examples of the enjoyment dimensions (Cronbach’s α = 0.71).

3.2.9 Membership in Club 300

Participants were asked to indicate their membership in the Club 300 with either yes or no. The Club 300 which exists in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland is a special group of elite birdwatchers because of their high achievement and knowledge of birds. This organization was initially established by individuals who have had observed at least 300 different bird species in their respective country. Usually, it takes some years to achieve this goal, although it is possible to see 300 bird species within Germany within one year, but this requests a lot of travelling and spending many hours of birdwatching (comparable to a Big Year). The members receive alerts about when and where a rare species has been detected. Nowadays, the group is open for everybody, so people with a country list less than 300 species can join this group, but it still contains a majority of birdwatchers with a high number of species on their list.

3.3 Statistical Analysis

Only participants with less than 15% of missing data were used. Different analytical strategies were employed. First, a multivariate general linear model was used to check the significant effects using partial eta-squares as a measure of effect sizes. The different dimensions and scales (birding specialization, involvement, and motivations) were used as dependent variables and membership as independent variable to predict differences between both groups. Partial eta-squared values are interpreted following Richardson (2011) with 0.01, 0.06, and 0.14, being a small, medium and large effect. Afterwards, univariate linear models were used to analyze the effects of Club 300 membership on the different scales of birding specialization. ANOVAs were used to assess post-hoc tests of organization (with Bonferroni correction). To shed more light on the open ended-questions of the specialization dimensions skill/knowledge and behaviour, the raw data were examined. Further, to determine the factors that predict a Club 300 membership, a binary logistic regression model was used, with the predictors age, gender, graduation, and the dimensions as independent predictors. Both, the full regression model was applied as well as a forward stepwise model based on Wald statistics.

4 Results

A total of 2963 people responded with yes (N = 326, 11%) or no (N = 2637, 89%) to the question of a membership in the Club 300. There were 1550 men, 1398 women, and 15 diverse participants. Club 300 participants were from Germany (N = 255), N = 25 from Austria, and N = 46 from Switzerland. More men (N = 275) than women were Club 300 members participating in this study (N = 49; χ2 = 150.85, p < 0.001). From the total sample, a total of N = 284 (9.6%) reported to have a PhD as their highest degree, n = 1399 (47.2%) had bachelor or master’s degree from a university, n = 559 (18.9%) had Matura (university entrance exam; 12/13 years of schooling), n = 492 (16.6%) were from middle stratification level (10 years of schooling) and n = 143 (4.8%) reported 9 years of schooling. Finally, n = 86 (2.9%) reported a different degree. Differences in specialization, involvement, and motivation are depicted in Table 1.

A general linear multivariate model revealed a significant influence of Club 300 membership on the total set of the different dependent dimensions (Wilk’s λ = 0.685, F = 111.209, p < 0.001), with a partial eta-squared of 0.315, representing a high effect size. Subsequent univariate models revealed significant differences in all dimensions, but weak to negligible effects in competition and enjoyment motivation (Table 2). Thus, Club 300 members show the same motivation to enjoy nature as non-members (Table 2).

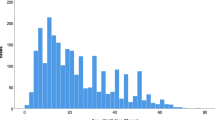

Effect sizes were highest concerning birding specialization and lowest with regard to motivations. Thus, the participants differed strongly in their specialization level. Therefore, the single items with the open-ended questions of the specialization scales behavior and skill/knowledge were analyzed separately. The statistics were carried out on the z-transformed data, but for convenience and comparison the untransformed values were used in Fig. 1.

There were striking and significantly high differences in all comparisons (p < 0.001). Differences in replacement value of the equipment were high with Club 300 members reporting on average 5795 € versus 1961 € for non-members. Club 300 members on average can identify a four-fold number of bird species without a field guide compared with non-members. Also, their life-list is four times, and their country list three times longer compared with non-members. In addition, the Club 300 members spend a considerably higher amount of time in the field.

The binary logistic regression to predict the Club 300 membership revealed the same results either when applying the full model or the stepwise forward procedure (χ2 = 748.528, p < 0.001, df = 18; Nagelkerke’s R-squared: 0.496). Hence, the full model is presented in Table 3.

Strong predictors of Club 300 membership were behavior, skill/knowledge, and behavioral commitment, concerning the specialization dimensions. People scoring high on these scales more probably were members of the Club 300. Concerning involvement, only the attraction dimension had a significant influence, but not centrality to lifestyle or identity. Thus, people can experience the same type of identity as a birder or the same importance that birds have for their lives irrespective of a membership. All three motivation scales contributed significantly to the model, but with enjoyment of nature in a negative direction. In contrast, competition motivation showed the strongest influence concerning the motivational scales. Club 300 members also differed in social motivations, meaning that the social dimension of birding is more important for them than for non-members. Concerning demographics, gender and age were not significant, and graduation showed that more Club 300 members hold a PhD degree than non-members (χ2 = 10.50; p = 0.001, with continuity correction).

5 Discussion

This is one of the first studies concerning the highly specialized segment of elite birdwatchers (see, Scott et al., 1999). Elite birders differed significantly in their recreation specialization, thus elite birders have a higher knowledge, differ in their behaviour because they spent more time in the field, and finally, show a higher behavioral commitment. Thus, Club 300 members meet earlier studies’ criteria for high recreation specialization (e.g., Scott et al., 1999). The differences in motivations were weaker but still substantial. Going to the details, similar to Scott et al. (1999), skill/knowledge and personal and behavioural commitment were among the most important factors separating elite (Club 300) members from non-members, and participants from the Texas Birding Classic from average ABA members (Scott et al., 1999). Both studies focus on the extreme end of birding. Scott et al. (1999) studied the participants directly at the Texas Birding Classic event, while this study focused on Club 300 membership. However, both, the Texas Birding Classic and the Club 300 membership include many years of keen birdwatching and focus on the elite recreation specialization. Differences between both studies exist in life-lists, the total number of birds observed in ones’ lifetime, with 1,139 species in the US American sample (Scott et al., 1999) compared to 851 in this central European sample.

The present study showed that Club 300 members fulfil the requirements of devotees to serious leisure or elite birders (Scott & McMahan, 2017) because they have a high specialization in knowledge and behavior, and in behavioural commitment. Thus, this group differs in leisure behaviour in its widest sense from other birdwatchers. Nevertheless, differences in the psychological aspects and in involvement are smaller, e.g., in the centrality to lifestyle or in identity. This means that non-members and members feel the same importance of birds for their life, and birds play a central role in both groups. Thus, birds can be important for ones’ life and for ones’ leisure activities, but this does not necessarily result in becoming an elite birder.

Concerning motivations, in contrast to Scott et al. (1999) who reported that competitive motives were not the highest motivational factor, in this study, competition formed a high motivational factor. This is also in contrast to previous work on non-birders. Participants identified as elite devotees in another leisure activity (golf) enjoyed the challenge, but not for competition, rather for personal enrichment (Siegenthaler and O'Dell, 2003; Tinsley & Eldredge, 1995). The difference can be explained in that the Club 300 has some competitive elements on its website that allow, e.g., comparing of participants’ national lists, lists of other geographic regions (western palearctic) and in year listings of country records, as well as a special “self-found” competition where only self-found birds are counted. Also, Club 300 members can bird on their own as singletons or in groups, while Texas Birding Classic participants form teams that compete with other teams.

In line with previous work, the social motives are high for Club 300 members, and even higher in comparison to non-members. It can only be speculated about this, but working together to find difficult birds, or enjoying the delighting moments when after a long time of searching a rare species is (re-)located may form special bonds between people (Snetsinger, 2003). It would be a worthwhile task, doing some exploratory qualitative work on the social dimension of birding, e.g., by interviews to address this question. Although enjoyment motivation was ranked higher than achievement/competition and social motivations in both groups, enjoyment of nature was negatively related to membership in the binary logistic regression. This can be interpreted in a way that non-members may primarily go out to watch birds, while experienced and highly skilled birders may go birding to discover “something special”, which can be experienced as some kind of pressure. To further investigate this question, perhaps other models of human motivations in addition to the Decker et al. (1987) model may be applied.

As a conclusion, this study shows empirical support for the recreation specialization concept. Further, it suggests that the dimensions of behaviour and of skill/knowledge are the main dimensions that delineate the elite birder recreationists from the non-members. Further studies in elite recreationists in other fields or disciplines may specifically focus on the aspects of behavior and knowledge. Therefore, the recreation specialization concept seems a good concept to address elite leisure. This concept should be applied and studied in further work on other leisure activities with a high diversity of recreation specialization. In addition, this study, together with previous work, shows that recreation specialization and serious leisure include a specific segment of elite devotees, and this segment may be important to develop the theoretical framework of both concepts further (serious leisure; recreation specialization). From a measurement viewpoint, developing empirical, psychometric measures to address this elite segment would be very useful, especially when they are short and easy to apply. In combination with this study, it may be most useful focusing on the behavioural dimension and on skill/knowledge. Further, as some differences (especially in motivations) showed weaker differences, new questions (e.g., about commitment) might be developed to better discriminate between the elite segment and others.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the author.

References

Booth, J. E., Gaston, K. J., Evans, K. L., & Armsworth, P. R. (2011). The value of species rarity in biodiversity recreation: A birdwatching example. Biological Conservation, 144(11), 2728–2732.

Brown, C. A. (2007). The Carolina shaggers: Dance as serious leisure. Journal of Leisure Research, 39(4), 623–647.

Bryan, H. (1977). Leisure value systems and recreation specialisation. Journal of Leisure Research, 9, 174–187.

Bryan, H. (2000). Recreation specialization revisited. Journal of Leisure Research, 32(1), 18–21.

Butler, R. W. (2019). Niche tourism (birdwatching) and its impacts on the well-being of a remote island and its residents. International Journal of Tourism Anthropology, 7(1), 5–20.

Callaghan, C. T., Slater, M., Major, R. E., Morrison, M., Martin, J. M., & Kingsford, R. T. (2018). Travelling birds generate eco-travellers: The economic potential of vagrant birdwatching. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 23(1), 71–82.

Cheung, L. T., Lo, A. Y., & Fok, L. (2017). Recreational specialization and ecologically responsible behaviour of Chinese birdwatchers in Hong Kong. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(6), 817–831.

Cole, J. S., & Scott, D. (1999). Segmenting participation in wildlife watching: A comparison of casual wildlife watchers and serious birders. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 4(4), 44–61.

Costa, A., Pintassilgo, P., Matias, A., Pinto, P., & Guimarães, M. H. (2018). Birdwatcher profile in the Ria Formosa Natural Park. Tourism & Management Studies, 14(1), 69–78.

Dayer, A. A., Rosenblatt, C., Bonter, D. N., Faulkner, H., Hall, R. J., Hochachka, W. M., … & Hawley, D. M. (2019). Observations at backyard bird feeders influence the emotions and actions of people that feed birds. People and Nature, 1(2), 138–151.

de Camargo Barbosa, K. V., Develey, P. F., & Ribeiro, M. C. (2021). The contribution of citizen science to research on migratory and urban birds in Brazil. Ornithology Research, 29(1), 1–11.

De Salvo, M., Cucuzza, G., Ientile, R., & Signorello, G. (2020). Does recreation specialization affect birders’ travel intention? Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 25(6), 560–574.

Decker, D. J., Brown, T. L., Driver, B. L., & Brown, P. J. (1987). Theoretical developments in assessing social values of wildlife: Toward a comprehensive understanding of wildlife recreation involvement. In D. J. Decker & G. R. Goff (Eds.), Valuing wildlife: Economic and social perspectives (pp. 76–95). Westview Press.

Eubanks, T. L., Jr., Stoll, J. R., & Ditton, R. B. (2004). Understanding the diversity of eight birder sub-populations: Socio-demographic characteristics, motivations, expenditures and net benefits. Journal of Ecotourism, 3(3), 151–172.

Goodfellow, D. L. (2013). Birds to baby dreaming: Connecting visitors to Bininj and wildlife in Australia’s Northern Territory. Journal of Ecotourism, 12(2), 112–118.

Goodfellow, D. (2015). American couples who travel internationally and watch birds: An exploration of their practices and attitudes to each other, birdwatching and travel. In Wilson, E. & Witsel, M. (Eds.), Rising tides and sea changes: Adaptation and innovation in tourism and hospitality, 479–482

Harshaw, H. W., Cole, N. W., Dayer, A. A., Rutter, J. D., Fulton, D. C., Raedeke, A. H., … & Duberstein, J. N. (2020). Testing a continuous measure of recreation specialization among birdwatchers. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 26(5), 472–480.

Hvenegaard, G. T. (2002). Birder specialization differences in conservation involvement, demographics, and motivations. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 7(1), 21–36.

Kyle, G., Absher, J., Norman, W., Hammitt, W., & Jodice, L. (2007). A modified involvement scale. Leisure Studies, 26(4), 399–427.

Lee, J. H., & Scott, D. (2004). Measuring birding specialization: A confirmatory factor analysis. Leisure Sciences, 26(3), 245–260.

Lee, S., & Scott, D. (2013). Empirical linkages between serious leisure and recreational specialization. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 18(6), 450–462.

Lessard, S. K., Morse, W. C., Lepczyk, C. A., & Seekamp, E. (2018). Perceptions of Whooping Cranes among waterfowl hunters in Alabama: Using specialization, awareness, knowledge, and attitudes to understand conservation behavior. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 23(3), 227–241.

Ma, Z., Cheng, Y., Wang, J., & Fu, X. (2013). The rapid development of birdwatching in mainland China: A new force for bird study and conservation. Bird Conservation International, 23(2), 259–269.

McFarlane, B. L. (1994). Specialization and motivations of birdwatchers. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 22(3), 361–370.

McFarlane, B. L., & Boxall, P. C. (1996). Participation in wildlife conservation by birdwatchers. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 1(3), 1–14.

Randler, C. (2021a). An analysis of heterogeneity in German speaking birdwatchers reveals three distinct clusters and gender differences. Birds, 2, 250–260.

Randler, C. (2021b). Users of a citizen science platform for bird data collection differ from other birdwatchers in knowledge and degree of specialization. Global Ecology and Conservation, 27, e01580.

Randler, C. (2023). Motivations for birdwatching: Support for a three-dimensional model. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 28(1), 84–92.

Randler, C., Adan, A., Antofie, M. M., Arrona-Palacios, A., Candido, M., Boeve-de Pauw, J., … & Vollmer, C. (2021). Animal Welfare Attitudes: Effects of Gender and Diet in University Samples from 22 Countries. Animals, 11(7), 1893.

Richardson, J. T. (2011). Eta squared and partial eta squared as measures of effect size in educational research. Educational Research Review, 6(2), 135–147.

Scott, D., Baker, S. M., & Kim, C. (1999). Motivations and commitments among participants in the Great Texas Birding Classic. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 4, 50–67.

Scott, D., & Shafer, C. S. (2001). Recreational specialization: A critical look at the construct. Journal of Leisure Research, 33(3), 319–343.

Scott, D., & Thigpen, J. (2003). Understanding the birder as tourist: Segmenting visitors to the Texas Hummer/Bird Celebration. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 8(3), 199–218.

Scott, D., Ditton, R. B., Stoll, J. R., & Eubanks, T. L., Jr. (2005). Measuring specialization among birders: Utility of a self-classification measure. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 10(1), 53–74.

Scott, D., & McMahan, K. K. (2017). Hard-core leisure: A conceptualization. Leisure Sciences, 39(6), 569–574.

Siegenthaler, K. L., & O’Dell, I. (2003). Older golfers: Serious leisure and successful aging. World Leisure Journal, 45(1), 45–52.

Snetsinger, P. (2003). Birding on borrowed time. American Birding Association.

Stebbins, R. A. (1982). Serious leisure: A conceptual statement. Pacific Sociological Review, 25, 251–272.

Stebbins, R. A. (1992). Amateurs, professionals, and serious leisure. McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP.

Stebbins, R. A. (2016). Dumazedier, the serious leisure perspective, and leisure in Brazil. World Leisure Journal, 58(3), 151–162.

Stebbins, R. A. (2017). Serious leisure: A perspective for our time. Routledge.

Stebbins, R. A. (2020). The serious leisure perspective: A synthesis. Springer Nature.

Sullivan, B. L., Aycrigg, J. L., Barry, J. H., Bonney, R. E., Bruns, N., Cooper, C. B., … & Kelling, S. (2014). The eBird enterprise: An integrated approach to development and application of citizen science. Biological Conservation, 169, 31–40.

Tinsley, H. E., & Eldredge, B. D. (1995). Psychological benefits of leisure participation: A taxonomy of leisure activities based on their need-gratifying properties. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42, 123–132.

Tsaur, S. H., & Liang, Y. W. (2008). Serious leisure and recreation specialization. Leisure Sciences, 30(4), 325–341.

U.S. Fish, & Wildlife Service. (2018). 2016 National Survey of Fishing. Hunting and Wildlife-Associated Recreation.

Acknowledgements

Naomi Staller established the website for the survey.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author reports no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was granted permission by the Faculty for Economics and Social Sciences of the University of Tübingen (A2.5.4-113_aa). Informed “written” consent was obtained via the website.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Randler, C. Elite Recreation Specialization and Motivations among Birdwatchers: The Case of Club 300 Members. Int J Sociol Leis 6, 209–223 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41978-022-00129-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41978-022-00129-3