Abstract

This paper studies the effects earthquakes have on inward foreign direct investment (FDI) within a country. I use a dynamic difference-in-difference model to estimate the impact of geophysical disaster exposure in 416 Indonesian districts. The effects are only temporary: FDI inflows plummet by 90% on average in the first year after an earthquake before recovering to pre-earthquake levels. The effect is largely driven by shocks through affected upstream industries within local supply chains, and centered within the manufacturing sector. This highlights the importance to also consider indirect earthquake effects through spatial and production networks, besides the direct effects on labor and capital.

Similar content being viewed by others

Availability of data, code and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to copyright reasons of some sub-data sets, but are available from the corresponding author on request.

Notes

Yet flood, as the second most common category, is also assessed for robustness.

Per UNDRR (2022a) definition direct refers to victims:"persons whose goods and/or individual or collective services have suffered serious damage, directly associated with the event" and indirect refers to affected: "people, distinct from victims, who suffer the impact of secondary effects of disasters for such reasons as deficiencies in public services, commerce, work"

The population data is only available until 2014. All years after 2014 are imputed using the district-specific linear population trends

In contrast to the scale, which is measured at the epicenter.

In relative terms this approach identifies 7% of districts as economic centers. This value reaches 20% in the highest illuminated districts. The value is lower on average due to many non-illuminated cells. As a quintile approach is used the spatial size of an economic center depends on the size of the district. To validate if the nighttime light indeed proxies economic centers, it is cross-referenced against geolocations of cities in Supplementary Information Appendix G2.

The precise definition for district i and year t is

$$ \text {Shock}_{it}=\underbrace{(\text {MMI}_{it}^{\text {urban}})}_{\text {Capital Shock}} \times \underbrace{(\frac{\text {Deaths}_{it}+\text {Victims}_{it}+\text {Affected}_{it}}{\text {Population}_{i,t-1}^{\text {imp}}})}_{\text {Labor Market Shock}}$$Indonesia is divided into provinces (level 1), regencies and cities (level 2), districts (level 3) and villages (level 4). So the second administrative level refers to 416 regencies (kabupaten) and 98 cities (kota), but for simplicity all second-level entities are called districts to align the name with the common perception of districts being the level below provinces.

Based on victim records within the Desinventar database. This dummy equals one if more than 20 people are affected by any disaster type other than earthquakes or earthquake-induced tsunamis.

The I-O table is sector-wise aggregated to match the corresponding FDI sectors and converted to the Leontief inverse matrix

Conversion follows Bellemare and Wichman (2020) (equation 11) of arcsin-dummy conversion: \(exp(\beta )-1\)

Two estimators suggest a small pre-trend. This trend is, however, not significant on any standard level.

References

Acemoglu D, Akcigit U, Kerr W (2016) Networks and the macroeconomy: An empirical exploration. NBER Macroecon Annu 30:273–335. https://doi.org/10.1086/685961

Antonioli D, Marzucchi A, Modica M (2021) Resilience, performance and strategies in firms’ reactions to the direct and indirect effects of a natural disaster. Netw Spat Econ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11067-021-09521-0

Anuchitworawong C, Thampanishvong K (2015) Determinants of foreign direct investment in thailand: Does natural disaster matter? Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 14:312–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2014.09.001

Badan Pusat Statistik (2021) Tabel interregional input-output indonesia tahun 2016 tahun anggaran 2021. Retrieved from https://www.bps.go.id/publication/2021/12/29/3ea49c0d856eceaba836792d/tabelinterregional-input-output-indonesia-tahun-2016-tahun-anggaran-2021.html. Date accessed: 05/09/2022

Batala LK, Yu W, Khan A, Regmi K, Wang X (2021) Natural disasters’ influence on industrial growth, foreign direct investment, and export performance in the south asian region of belt and road initiative. Nat Hazards 108:1853–1876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-021-04759-w

Bellemare MF, Wichman CJ (2020) 2). Elasticities and the inverse hyperbolic sine transformation. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 82:50–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/obes.12325

Boehm CE, Flaaen A, Pandalai-Nayar N (2019) Input linkages and the transmission of shocks: Firm-level evidence from the 2011 tōhoku earthquake. Rev Econ Stat 101:60–75. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a00750

Borusyak K (2022) Five_estimators_example.do. Retrieved from https://github.com/borusyak/did_imputation/blob/main/five_estimators_example.do. Date accessed: 10/03/2022

Borusyak K, Jaravel X, Spiess J (2021) Revisiting event study designs: Robust and efficient estimation. ArXiv.org , Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/2108.12419

Brucal A, Mathews S (2021) Market entry, survival, and exit of firms in the aftermath of natural hazard-related disasters: A case study of indonesian manufacturing plants

Carvalho VM, Nirei M, Saito YU, Tahbaz-Salehi A (2021) Supply chain disruptions: Evidence from the great east japan earthquake. Q J Econ 136:1255–1321. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjaa044

Chen Z, Yu B, Yang C, Zhou Y, Yao S, Qian X, ..., Wu J (2021) An extended time series (2000–2018) of global npp-viirs-like nighttime light data from a cross-sensor calibration. Earth Syst Sci Data 13:889–906. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-13-889-2021

Cole MA, Elliott RJR, Okubo T, Strobl E (2019) Natural disasters and spatial heterogeneity in damages: the birth, life and death of manufacturing plants. J Econ Geogr 19:373–408. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbx037

De Chaisemartin C, d’Haultfoeuille X (2020) Two-way fixed effects estimators with heterogeneous treatment effects. Am Econ Rev 110:2964–2996. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20181169

De Chaisemartin C, D’Haultfoeuille X (2023) Two-way fixed effects and differences-in-differences estimators with several treatments. J Econom 236(2):105480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2023.105480

Doytch N (2019) Upgrading destruction? Int J Clim Chang Strateg Manag 12:182–200. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCCSM-07-2019-0044

Drabo A (2021) How do climate shocks affect the impact of fdi, oda and remittances on economic growth? IMF Working Papers, 2021 , 1. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781513585635.001

Elliott RJ, Liu Y, Strobl E, Tong M (2019) Estimating the direct and indirect impact of typhoons on plant performance: Evidence from chinese manufacturers. J Env Econ Manag 98:102252. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JEEM.2019.102252

Emrich CT, Zhou Y, Aksha SK, Longenecker HE (2022) Creating a nationwide composite hazard index using empirically based threat assessment approaches applied to open geospatial data. Sustainability 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052685

Felbermayr G, Gröschl J (2014) Naturally negative: The growth effects of natural disasters. J Dev Econ 111:92–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2014.07.004

Felbermayr G, Gröschl J, Sanders M, Schippers V, Steinwachs T (2022) The economic impact of weather anomalies. World Dev 151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105745

Friedt FL, Toner-Rodgers A (2022) Natural disasters, intra-national fdi spillovers, and economic divergence: Evidence from india. J Dev Econ 157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2022.102872

Galbusera L, Giannopoulos G (2018) On input-output economic models in disaster impact assessment. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 30:186–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.04.030

Gignoux J, Menéndez M (2016) Benefit in the wake of disaster: Long-run effects of earthquakes on welfare in rural indonesia. J Dev Econ 118:26–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2015.08.004

Goodman S, BenYishay A, Lv Z, Runfola D (2019) Geoquery: Integrating hpc systems and public web-based geospatial data tools. Comput Geosci 122:103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2018.10.009

Goodman-Bacon A (2021) Difference-in-differences with variation in treatment timing. J Econom 225:254–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2021.03.014

Gu GW, Hale G (2023) Climate risks and fdi. J Int Econ. 103731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2023.103731

Hallegatte S (2008) An adaptive regional input-output model and its application to the assessment of the economic cost of katrina. Risk Anal 28:779–799. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01046.x

Hu Y, Yao J (2019) Illuminating economic growth. International Monetary Fund

Huang R, Malik A, Lenzen M, Jin Y, Wang Y, Faturay F, Zhu Z (2022) Supply-chain impacts of sichuan earthquake: A case study using disaster input-output analysis. Nat Hazards 110:2227–2248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-021-05034-8

Imai K, Kim IS, Wang EH (2023) Matching Methods for Causal Inference with Time-Series Cross-Sectional Data. Am J Polit Sci 67(3):587–605. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12685

Indonesian Investment Co-ordinating Board (BKPM) (2021) Panduan penggunaan. Retrieved from https://nswi.bkpm.go.id/. Date accessed: 10/12/2021

Inoue H, Todo Y (2019) Firm-level propagation of shocks through supply-chain networks. Nat Sustain 2:841–847. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0351-x

Javorcik BS, Özden Ç, Spatareanu M, Neagu C (2011) Migrant networks and foreign direct investment. J Dev Econ 94:231–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.01.012

Kato H, Okubo T (2022) The resilience of fdi to natural disasters through industrial linkages. Environ Resour Econ 82:177–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-022-00666-1

Katoka B (2021) Do natural disasters reduce foreign direct investment in subsaharan africa? Econ Eff Nat Disaster 529–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-817465-4.00031-5

Kugler M, Rapoport H (2007) International labor and capital flows: Complements or substitutes? Econ Lett 94:155–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2006.06.023

Lehman W, Light MK, Nugent R, Burns J (2022) Economic consequences assessment model (ecam): A tool & methodology for measuring indirect economic effects. Retrieved from https://www.undrr.org/publication/economicconsequences-assessment-model-ecam-tool-methodology-measuring-indirect

Lipsey RE, Sjöholm F (2011) Foreign direct investment and growth in east asia: lessons for indonesia. Bull Indones Econ Stud 47:35–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2011.556055

Minnesota Population Center (2020) Integrated public use microdata series (international: Version 7.3) [indonesia]

Neise T, Diez JR (2019) Adapt, move or surrender? manufacturing firms’ routines and dynamic capabilities on flood risk reduction in coastal cities of indonesia. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 33:332–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.10.018

Neise T, Sohns F, Breul M, Diez JR (2022) The effect of natural disasters on fdi attraction: A sector-based analysis over time and space. Nat Hazards 110:999–1023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-021-04976-3

OCHA’s Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific (2021) Indonesia - subnational administrative boundaries - humanitarian data exchange. Retrieved from https://data.humdata.org/dataset/indonesia-administrativeboundary-polygons-lines-and-places-levels-0-4b. Date accessed: 01/07/2021

OECD (2020) Oecd investment policy reviews: Indonesia 2020. Author. Retrieved from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/finance-and-investment/oecdinvestment-policy-reviews-indonesia-2020_b56512da-en

Pelli M, Tschopp J, Bezmaternykh N, Eklou K (2019) In the eye of the storm: Firms and capital destruction in india. SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3449708

Rambachan A, Roth J (2023) A More Credible Approach to Parallel Trends. Rev Econ Stud 90(5):2555–2591. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdad018 (https://academic.oup.com/restud/article/90/5/2555/7039335)

Rentschler J, Kim E, Thies S, De S, Robbe V, Erman A, Hallegatte S (2021) Floods and their impacts on firms evidence from tanzania. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/36282

Sant’Anna PH, Zhao J (2020) Doubly robust difference-in-differences estimators. J Econom 219:101–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.06.003

Sapir DG, Below R (2014) Em-dat: International disaster database. Université Catholique de Louvain, Brussels, Belgium www.emdat.be

SEDAC-CIESIN (2017) Gridded Population of the World, Version 4 (GPWv4): Population Density, Revision 11. https://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/data/set/gpwv4-population-density-rev11. Palisades, NY: Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC)

Steenbergen V, Hebous S, Wihardja MM, Pradana AT (2020) The effect of fdi on indonesia’s jobs, wages, and structural transformation. World Bank

Sun L, Abraham S (2021) Estimating dynamic treatment effects in event studies with heterogeneous treatment effects. J Econom 225:175–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.09.006

Sutton PC, Elvidge CD, Ghosh T (2007) Estimation of gross domestic product at sub-national scales using nighttime satellite imagery. Int J Ecol Econ Stat 8:5–21

Suyanto Salim RA, Bloch H (2009) Does foreign direct investment lead to productivity spillovers? firm level evidence from indonesia. World Dev 37:1861–1876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.05.009

The World Bank (2022a). Foreign direct investment, net inflows (% of gdp) - Indonesia. Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.KLT.DINV.WD.GD.ZS. Date accessed: 22/03/2022

The World Bank (2022b). Indonesia database for policy and economic research (indodapoer). Retrieved from https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/indonesiadatabase-policy-and-economic-research. Date accessed: 03/02/2022

UN Economic and Social Affairs (Population Division) (2019) International migrant stock 2019. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/international-migrantstock

UNCTAD (2017) World investment report 2017: Investment and the digital economy. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

UNCTAD (2021) Foreign direct investment: Inward and outward flows and stock, annual. Retrieved from https://unctadstat.unctad.org/. Date accessed: 04/05/2022

UNDRR (2022a). Definition of basic effects. Retrieved from https://www.desinventar.net/effects.html. Date accessed: 05/10/2022

UNDRR (2022b). Desinventar sendai - framework for disaster risk reduction. Retrieved from https://www.desinventar.net/DesInventar/results.jsp. Date accessed: 05/09/2022

US Geological Survey (2020) Anss comprehensive earthquake catalog (comcat)

USGS (2022) The modified mercalli intensity scale. Retrieved from https://www.usgs.gov/programs/earthquake-hazards/modified-mercalliintensity-scale. Date accessed: 05/09/2022

Wald DJ, Quitoriano V, Heaton TH, Kanamori H, Scrivner CW, Worden CB (1999) Trinet “shakemaps”: Rapid generation of peak ground motion and intensity maps for earthquakes in southern california (Vol. 15)

Wooldridge JM (2021) Two-way fixed effects, the two-way mundlak regression, and difference-in-differences estimators. SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3906345

Xu Y (2022) Causal inference with time-series cross-sectional data: A reflection. SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3979613

Zhu H, Duan L, Guo Y, Yu K (2016) The effects of fdi, economic growth and energy consumption on carbon emissions in asean-5: Evidence from panel quantile regression. Econ Model 58:237–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2016.05.003

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Lisa Chauvet, Sandra Poncet, Jérémie Gignoux, Ariell Reshef, Myriam Ramzy, Rémi Bazillier, Clément Bosquet, Andrea Cinque, Fabio Ascione, Thibault Lemaire, as well as the participants of several seminars and conferences. I am particularly grateful to Lisa Chauvet for the support of this work and actively engaging in its development. I also thank the Centre d’économie de la Sorbonne (CES), Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne for support during this research. The responsibility for all conclusions of this paper lie entirely with the author.

Funding

The author declares that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

Development of FDI inflows over time by sector The data is based on Indonesian Investment Co-ordinating Board (BKPM) (2021). Author’s own assignement

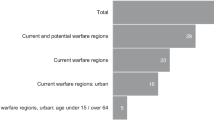

Effects on District-level. The two panels show the effects of Eq. 1 if one extends the model towards the sectoral annual FDI space. Classification of FDI sectors follows broadly ISIC Rev. 3 level 2. The bars depict the 95% intervals and stars indicate *** 1%, ** 5% and * 10% significance. The left panel shows the effect over time, whereas the right one shows the effect solely in the year after the earthquake event (yet using the same regression as before). The treated group includes 38 treated districts and excludes as before treatment reversal and simultaneously occurring disaster events

Comparison of different recent DiD estimators. All included estimates allow staggered treatment design, yet exclude the possibility of treatment reversal. Here, each individual regression excludes multiple treatments within unit and uses only a sample of districts, which did not change names over the period (omitting 5% of the sample), which does not affect estimates substantially. The code is inspired by Borusyak (2022) and presents estimators by Sun and Abraham (2021); Sant’Anna and Zhao (2020); De Chaisemartin and d’Haultfoeuille (2020); Borusyak et al. (2021); Wooldridge (2021). The chosen CI bandwidth is the 10% threshold

Effects using panel matching. The panels show the effect of earthquake exposure onto FDI inflows, where control units show a similar treatment pattern and are matched. This method is based on Imai et al. (2023). The upper panel excludes districts with more than a single earthquake recorded, the lower excludes districts with only a single earthquake recorded. The three columns show three different matching algorithms for building a control group. The different columns show how many pre-treatment periods are used to build a matching control group. Matching covariates are based on the last three lags of nighttime-light, three lags of arcsin FDI inflow, current log of population and time-invariant composite hazard risk index. All most use matched control group of sample size 10 and standard errors are 1000 times bootstrapped. The confidence intervals shown correspond to a 10% threshold

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Reinhardt, R. Shaking up Foreign Finance: FDI in a Post-Disaster World. EconDisCliCha (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-024-00148-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-024-00148-2